Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of a research training program on clinicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to research and evidence-based practice (EBP).

BACKGROUND:

EBP has been shown to improve patient care and outcomes. Innovative approaches are needed to overcome individual and organizational barriers to EBP.

METHODS:

Mixed-methods design was used to evaluate a research training intervention with point-of-care clinicians in a Canadian urban health organization. Participants completed the Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practice Survey over 3 timepoints. Focus groups and interviews were also conducted.

RESULTS:

Statistically significant improvement in research knowledge and ability was demonstrated. Participants and administrators identified benefits of the training program, including the impact on EBP.

CONCLUSIONS:

Providing research training opportunities to point-of-care clinicians is a promising strategy for healthcare organizations seeking to promote EBP, empower clinicians, and showcase excellence in clinical research.

Research confirms that patient outcomes improve when nurses practice in an evidence-based manner. Described as “a problem-solving approach to clinical care that incorporates the conscientious use of current best practice from well-designed studies, a clinician’s expertise, and patient values and preferences,”1(p335) evidence-based practice (EBP) has been shown to increase patient safety, improve clinical outcomes, reduce healthcare costs, and decrease variation in patient outcomes.1-4 The importance of EBP is substantiated; however, barriers to widespread use of current research evidence in nursing remain, including the fluency and knowledge level of clinical nurses.

Nurses have identified individual and organizational barriers to research utilization. Individual barriers include lack of knowledge about the research process and how to critique research studies, lack of awareness of research, colleagues not supportive of practice change, and nurses feeling a lack of authority to change practice.5-8 Organizational barriers identified include insufficient time to implement new ideas, lack of access to research, and lack of awareness of available educational tools related to research.5-7,9-11

Research demonstrates that the most important factor related to nurses’ EBP is support from their employing organizations to use and conduct research.7,9 Other facilitators include the presence in the clinical setting of advanced practice nurses, research mentors, and educators knowledgeable about research12-16; nursing research internships17; and designated nurse-researchers.15 In their BARRIERS scale studies,18,19 Funk and colleagues recommended strategies for reducing barriers to EBP, including employment of research role models, establishment of collegial relationships with academics, and participation in research interest groups. Similar strategies have been more recently highlighted in the context of the Magnet Recognition Program®.15,16

There is, however, a notable lack of rigorous intervention studies focused on identifying organizational barriers to improve nurses’ engagement in EBP.20 Only 1 study focused on the implementation of Magnet® standards in American hospitals that showed promise in diminishing the barriers to EBP.21 To address this gap, leaders at a tertiary healthcare organization implemented a point-of-care research training program, led by the organization’s nursing research facilitator, targeting nurses and other clinicians to reduce EBP barriers and to promote engagement in research (Job Description for Nursing Research Facilitator, see Document, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JONA/A369). The program provided mentoring and funding for teams of novice researchers to conduct small-scale studies in their practice settings. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of the training program on clinicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to research and EBP.

Methods

A mixed-methods design22,23 was utilized to support the evaluation of the training program. A before-after survey design was used to assess the effect of the training program on clinicians, and focus groups and interviews were conducted with clinicians and administrators to explore their perceptions of the training program. Ethical approval was obtained from the appropriate institutional ethics board.

Sample and Sampling

Participants were recruited from organizational employees who had applied, in teams, to be part of the training program. Each research team was required to have at least 1 point-of-care clinician whose job was limited to clinical practice and did not include administrative or research responsibilities. A total of 27 teams and 153 clinicians (including 78 RNs) were accepted into the training program in 2 years (2011-2013). Of the 25 teams funded in the 1st 2 years, 10 teams were led by RNs, and 30 other nurses were team members of funded teams. These clinicians were invited to complete a baseline survey and 2 follow-up surveys as well as participate in focus groups. The administrative leaders of these clinicians were invited to participate in qualitative interviews.

Intervention

Potential research teams submitted letters of intent that outlined the team membership and the proposed research problem, which were reviewed for feasibility and clinical significance by an advisory committee composed of academic and clinical leaders. Approved teams were invited to join the training program and assigned a research mentor to assist in the development of the full research proposal. Research teams attended 3 research workshops that provided foundational knowledge about research methods, research ethics, and literature review techniques (see Document, Supplemental Digital Content 2, which shows a curriculum sample, http://links.lww.com/JONA/A370). Following the workshops, research teams had 3 months to develop a brief proposal, in consultation with their assigned mentor. The proposals were evaluated for their feasibility, significance, and soundness of design, and those funded received small research grants (Can $2,000-$5,000). Over the next year, funded teams conducted their research studies and engaged in knowledge translation activities.

Instruments

Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practice Survey

The Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practice (KAP) survey is an instrument that assesses 33 research activities that an RN or other health professional might encounter in clinical practice, including utilization and conduct of research. The KAP consists of 5 factors: (1) identifying clinical problems, (2) establishing current best practice, (3) implementing research into practice, (4) administering research implementation, and (5) conducting and communicating. For each activity listed on the survey, the participants indicated their level of knowledge, willingness to engage (attitudes), and ability to perform (practices) specific research and knowledge translation activity on a 3-point scale. The KAP has strong content and construct validity and is a reliable measure (ie, internal consistency = .93 to .97)24 that has been used extensively in studies exploring EBP in nursing and other health professions.

A brief demographic form (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/JONA/A371), including age, gender, profession, position, level of education, years in practice, and practice area, was completed by participants at the time of enrollment.

Data Collection

Surveys

The instruments were administered through an online survey program (FluidSurveys; Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) and were administered in 3 waves at various stages of the training program (Figure 1). The baseline survey (survey 1) was conducted at the time of program enrollment. Survey 2 was conducted 3 months later, after participants completed the research workshops and submitted their proposals. The final survey (survey 3) was done at the end of the program after participants completed their projects, which ranged from 18 to 24 months from baseline. The final data collection timepoint varied because of extraneous circumstances (eg, slow accrual, loss of team members) that resulted in some teams requiring additional time to complete their research.

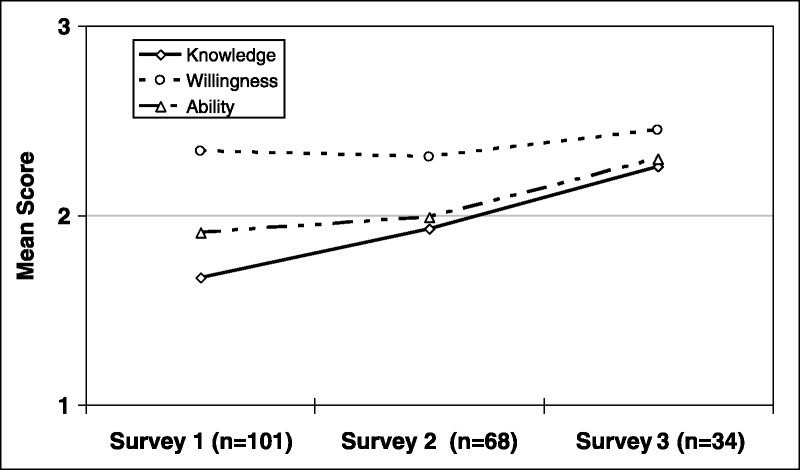

Figure 1.

Mean scores on research knowledge, willingness, and ability to conduct research.

Focus Groups and Qualitative Interviews

All participants of the funded research teams were invited to participate in focus groups scheduled within 6 months of the completion of their projects. Open-ended questions were used to explore participants’ experiences in the training program and the impact on their ability to engage in EBP. Several participants who were unable to take part in the focus groups completed individual interviews. A $20 gift card was provided to compensate focus group and interview participants. Key informant interviews were conducted with administrators whose staff participated in the program and gathered their perceptions regarding the impact of the program on clinicians’ ability to engage in research and EBP.

Data Analysis

Demographic characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics. Knowledge, willingness, and ability levels across survey waves were summarized using means and SDs. Linear mixed regression analyses comparing outcome measures between survey timepoints were performed to evaluate the impact of training at various stages of the program. This analytic approach was chosen to account for the correlation among measures from the same subject and to include participants with missing data, which were mostly caused by participants not completing all 3 surveys. To facilitate interpretation and where appropriate, average differences in the mean scores of the outcomes between survey waves were expressed as standardized effect sizes (Cohen d). Statistical data analyses were performed using version 9.2 of the SAS system (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina; 2008) for Windows.

The focus groups and interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcriptions were analyzed line-by-line for emerging concepts, which were developed into a coding scheme. Transcripts were coded and validated by at least 2 investigators, and disagreements were discussed until consensus. Coded data were entered into a qualitative management software program (NVivo; QSR International (Americas) Inc, Burlington, Massachusetts). Key themes and relationships were identified using a thematic analytical approach and confirmed by multiple research team members.

Results

Quantitative Findings

There were 136 participants in the study (response rate of 88.9%) (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/JONA/A371), mostly women (87%), between 25 and 44 years of age (80%), and working in acute care (85%). Approximately half of the participants were nurses (52%), had a baccalaureate degree (55%), and had been in practice for more than 10 years (58%). Except for education, no statistically significant differences in outcome measures by demographic characteristics were observed at baseline.

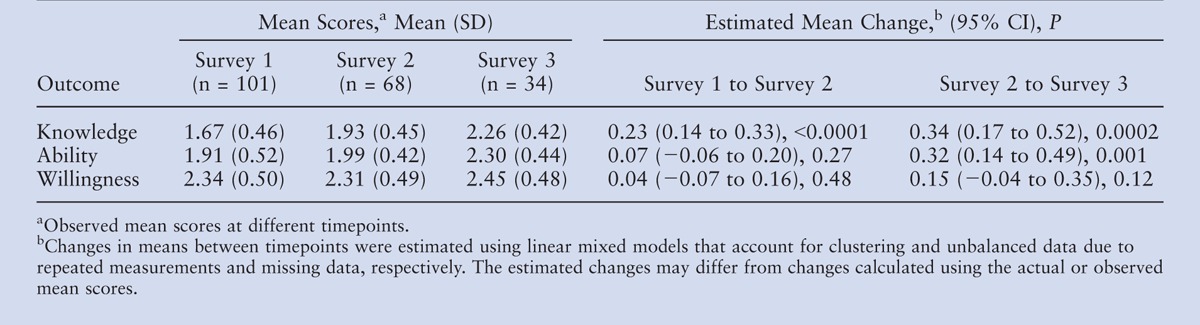

Research Knowledge

A significant improvement in research knowledge was found following participation in the research workshops and submission of the proposals (Table 1), with the observed mean knowledge score increasing from 1.67 (on a scale of 1 to 3) at baseline to 1.93 at survey 2. The change in mean scores between the 2 surveys, estimated using linear mixed models, was 0.23 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.14-0.33) and was statistically significant (P < .0001). This estimated difference in mean scores represents a change that was moderate in magnitude (d = 0.50). Further significant improvement in research knowledge was achieved following the completion of funded research projects, with an estimated increase in mean scores from survey 2 to survey 3 of 0.34 (95% CI, 0.17-0.52), indicating a large effect size (d = 0.77).

Table 1.

Means and Estimated Changes in Mean Scores on Research Knowledge, Willingness, and Ability Across Survey Timepoints

Research Ability

Participants’ perceived ability to conduct research did not significantly increase from survey 1 to survey 2 but improved considerably after completion of the research project (Table). The observed mean score on survey 2 was 1.99 (on a scale of 1 to 3) and increased to 2.30 in survey 3. The estimated change in mean scores based on the linear mixed models was 0.32 and was statistically significant (P = .001). This estimated change represents a large effect size (d = 0.74).

Research Willingness

No significant improvement in willingness to conduct research was noted across the study (Table 1). Mean scores remained at the upper end of the rating scale (on a scale of 1 to 3) throughout the study period, starting from the observed mean score of 2.34 at baseline, decreasing slightly to 2.31 at survey 2 and increasing to 2.45 in the final survey (Figure 1). The estimated change in mean scores was small (survey 1 to 2 = 0.04, survey 2 to 3 = 0.15).

Qualitative Findings

Three key themes emerged from the qualitative data: benefits from participating in the training program, impact of the training program on EBP, and challenges faced by beginning researchers.

Benefits of Training Program Participation

Administrators were overwhelmingly positive about the benefits of the training program for both clinicians and their organization. They perceived the program as filling a gap by offering education, mentorship, and funding to support clinicians’ engagement in the generation of evidence. Participants described the program as providing an important opportunity to learn and engage in research and knowledge translation activities that are rarely available to those without advanced education. Participants reported being less intimidated by research, having a greater appreciation for the complexities and limitations of research, and being better prepared to understand and apply evidence appropriately within clinical settings. As 1 administrator noted, “They’re not afraid of research anymore….”

Both administrators and participants described the program as creating a sense of excitement and enthusiasm among the healthcare team about research. One administrator described, “It was fun to see them evolve and develop in their journey as they took on this project. I saw a sense of confidence, a sense of ownership and pride.” For some participants, the program broadened their perceived scope of practice and made their job more enjoyable. As shared by 1 participant, “You feel you are learning in your job. You want to feel you’re moving somewhere and not standing in the same spot. It’s great at making a job that you’re stable in exciting and progressive.”

The training program was further perceived to benefit the organization by showcasing excellence in nursing and other professions among the larger healthcare community: “Because of the program, we were able to present papers at our national conference, which is an advantage for our [organization]….” Interprofessional collaboration within the organization, as well as partnerships between clinicians, administrators, and academics, was seen to be strengthened as a result of the program.

Increase in Evidence-Based Practice

The link between participation in the training program and promotion of EBP was clearly articulated by both administrators and participants. In particular, participants saw the training program as cultivating critical thinking:

It encourages you to seek answers regarding how things can improve or the effectiveness of certain methods and to search out and emphasize an evidence-based practice. This has been wonderful to open your eyes to all the different things you can do for your patients.

Administrators perceived the training program to raise awareness of the links between good clinical practice and research evidence:

There is more of an understanding or realization that whatever we implement or whatever practice we are carrying out, we do need to be more conscious of whether there is any evidence for it. There is more intentional scrutiny of what we are doing now, and the training program certainly reinforced that.

The training program also enhanced participants’ ability to advocate for change in the larger healthcare organization. Not only did they gain the language, resources, and evidence needed to be taken seriously by other members of the healthcare team, but also their motivation and commitment to promote practice change were enhanced by their engagement in the research process:

It makes the frontline workers really push to get the best possible evidence-based guidelines and practice because they want it. They know it’s better based on their really hard data collection and analyzing of the results. [It ] gives you buy-in… through blood, sweat, and tears.

Some participants and their teams did report practice change to result from their research, including shifts in practice guidelines and care standards. Three examples of practice and policy changes as a result of the training program and subsequent research included (1) a qualitative project that examined the experience of newly admitted residents to a long-term-care facility altered their admission process as a result of their findings; (2) a team in acute care developed a new order set that has significantly reduced emergency room wait times for myocardial infarction patients prescribed the hypothermia protocol; and (3) findings from a hemophilia study have led to implementation of individualized hemophilia treatment plans at the provincial hemophilia clinic and funding of an expanded study.

Challenges for Beginning Researchers and Recommendations

Despite the benefits noted by administrators and participants, the training program and the completion of the research project were challenging for most point-of-care clinicians. Not surprisingly, lack of time was a major hurdle mentioned by many participants, who described completing the training program “off the side of my desk.” Particularly onerous were the ethics application process and the recruitment of study participants.

Research mentors and the program organizers were perceived by participants to be invaluable in assisting them in navigating the complex research process. As 1 participant commented, “Whenever you got stuck, they were there when you needed them.” Also important was having a supportive administrator who understood clinicians’ conflicting demands and offered flexibility with regard to scheduling and resources. Further training in conducting data collection and analysis, as well as developing dissemination products, was suggested by several participants.

Discussion

This study is 1 of the 1st to implement and evaluate an EBP intervention that aimed to increase awareness and the practice of EBP through the inclusion of point-of-care clinicians in the creation of research evidence. This innovative approach bridged the traditional gap between clinical practice and research by empowering clinicians to identify challenging clinical issues and providing them with the knowledge, skills, and resources needed to look for solutions in an evidence-based manner. By involving point-of-care clinicians in research, we hoped to build excitement about research and EBP in the workplace.

The results of this study show that a research training program can successfully increase clinicians’ research knowledge and abilities, as well as offer them a sense of confidence and excitement about their clinical practice. Willingness to engage in research, however, did not significantly change. Participants’ willingness to take part in future research may have also been tempered by the time barrier discussed by many of the participants, as well as their realization of the challenges inherent in conducting research.

A variety of other strategies have been proposed to promote EBP among clinicians, including journal clubs,25-27 EBP education programs,28,29 knowledge brokers,30 and mentorship programs.31,32 Despite some of these interventions showing promise with regard to shifting attitudes towards EBP,25-31 not all have been effective in changing behavior related to EBP over time.33,34 While the impact of the training program on EBP was not quantitatively assessed in this study, both clinicians and administrators observed substantial changes to participants’ critical thinking and awareness of the interrelatedness of research and practice. Most striking was the number of participants who reported an increased commitment to practice improvement as well as shifts in clinical practice through revisions to practice guidelines and the development of patient and professional resources.

The research training program successfully addressed many of the barriers to EBP that have been previously identified.4-7 Support from all levels of leadership at the healthcare organization was acknowledged by participants as being integral to their ability to engage in the program, as was access to financial resources and academic mentors. Although many participants still struggled to balance competing priorities, their willingness to engage in research was maintained over the course of the training program. Training programs, such as the 1 tested in this study, create a culture of learning and respect in a healthcare organization for the pivotal role played by clinicians in not only utilizing research but also generating evidence and becoming change agents.

The importance of knowledge translation in healthcare has received much attention and scholarship in recent years, with efforts focused on increasing uptake of new research evidence by point-of-care clinicians.35-37 Although knowledge translation was not formally assessed as an outcome in this study, participants have enthusiastically pursued opportunities to share their experience and findings through more than 40 conference presentations and 3 peer-reviewed publications. In addition, 2 research teams have been successful in securing national funding to expand their original studies. These activities suggest that a research training program holds the potential to build research capacity in a healthcare organization (see Document, Supplemental Digital Content 4, which shows the Research Challenge Team and Project List, http://links.lww.com/JONA/A372).

There were several limitations to the study. The sample was restricted to clinicians working at a Canadian healthcare organization. Although the sample was diverse with regard to age, health disciplines, and years in practice, the majority of participants were females practicing in acute care. Caution is thus needed in generalizing the findings to other clinical settings and populations. The biases inherent in a single group before/after study design must also be acknowledged, and future evaluation of the training program through a randomized clinical trial is required to provide more conclusive evidence. Lastly, the potential clustering effect among research team members, which could not be controlled in the data analysis due to the survey not collecting data on team membership, may have influenced the linear regression modeling results.

For administrators, the research training program illustrates a successful model for enhancing EBP while strengthening academic-practice partnerships and creating professional development opportunities for point-of-care clinicians. Support for such programs highlights the importance and value attributed to research and EBP, which may help brand a healthcare organization as one with a strong research culture that attracts and keeps the best and brightest clinicians.

Conclusion

Healthcare organizations can no longer afford for EBP to remain an abstract concept or an idealized competency. The research training program evaluated in this article is a promising initiative that brings EBP to life for point-of-care clinicians by not only highlighting the importance of research in clinical practice, but empowering them to take a leading role.

Footnotes

Funding for this project was received from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.jonajournal.com).

References

- 1. Fineout-Overholt E, Melnyk B, & Schultz A. Transforming health care from the inside out: advancing evidence-based practice in the 21st century. J Prof Nurs. 2005; 21: 335- 344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Peterson ED, Bynum DZ, & Roe MT. Association of evidence-based care processes and outcomes among patients with acute coronary syndromes: performance matters. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008; 23( 1): 50- 55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Considine J, & McGillivray B. An evidence-based practice approach to improving nursing care of acute stroke in an Australian emergency department. J Clin Nurs. 2010; 19( 1-2): 138- 144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. de Pedro-Gomez J, Morales-Asencio JM, & Bennasar-Veny M. Determining factors in evidence-based clinical practice among hospital and primary care nursing staff. J Adv Nurs. 2012; 68( 2): 452- 459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Squires JE, Estabrooks CA, Gustavsson P, & Wallin L. Individual determinants of research utilization by nurses: a systematic review update. Implement Sci. 2011; 6: 1- 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Udod SA, & Care WD. Setting the climate for evidence-based nursing practice: what is the leader’s role? Nurs Leadersh. 2004; 17( 4): 64- 75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Retsas A. Barriers to using research evidence in nursing practice. J Adv Nurs. 2000; 31( 3): 599- 606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chau JPC, Lopez V, & Thompson DR. A survey of Hong Kong nurses’ perceptions of barriers to and facilitators of research utilization. Res Nurs Health. 2008; 31( 6): 640- 649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Paramonczyk A. Barriers to implementing research in clinical practice. Can Nurs. 2005; 101( 3): 12- 15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leasure AR, Stirlen J, & Thompson C. Barriers and facilitators to the use of evidence-based best practices. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2008; 27( 2): 74- 84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chan GK, Barnason S, & Dakin CL. Barriers and perceived needs for understanding and using research among emergency nurses. J Emerg Nurs. 2011; 37( 1): 24- 31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gerrish K, Guillaume L, Kirshbaum M, McDonnell A, Tod A, & Nolan M. Factors influencing the contribution of advanced practice nurses to promoting evidence-based practice among front-line nurses: findings from a cross-sectional survey. J Adv Nurs. 2011; 67( 5): 1079- 1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chummun H, & Tiran D. Increasing research evidence in practice: a possible role for the consultant nurse. J Nurs Manag. 2008; 16( 3): 327- 333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grant HS, Stuhlmacher A, & Bonte-Eley S. Overcoming barriers to research utilization and evidence-based practice among staff nurses. J Nurses Staff Dev. 2012; 28( 4): 163- 165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wilson B, Kelly L, & Reifsnider E. Creative approaches to increasing hospital-based nursing research. J Nurs Adm. 2013; 43( 10): 80- 88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kelly K, Turner A, & Speroni K. National survey of hospital nursing research, Part 2. J Nurs Adm. 2013; 43( 10): 18- 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wells N, Free M, & Adams R. Nursing research internship: enhancing evidence-based practice among staff nurses. J Nurs Adm. 2007; 37( 3): 135- 143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Funk SG, Champagne MY, Wiese RA, & Tornquist EM. BARRIERS: the barriers to research utilization scale. Appl Nurs Res. 1991; 4( 1): 39- 45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Funk SG, Champagne MY, Wiese RA, & Tornquist EM. Barriers to using research findings in practice: the clinician’s perspective. Appl Nurs Res. 1991; 4( 2): 90- 95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Flodgren G, Rojas-Reyes MX, Cole N, & Foxcroft DR. Effectiveness of organisational infrastructures to promote evidence-based nursing practice. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012; 2 CD002212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Karkos B, & Peters K. A Magnet community hospital: fewer barriers to nursing research utilization. J Nurs Admin. 2006; 36( 7/8): 377- 382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sandelowski M. Combining qualitative and quantitative sampling, data collection, and analysis techniques in mixed method studies. Res Nurs Health. 2000; 23( 3): 246- 255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Johnson RB, & Onwuegbuzie AJ. Mixed methods research: a research paradigm whose time has come. Educ Res. 2004; 33( 7): 14- 26. [Google Scholar]

- 24. van Mullem C, Burke LJ, & Dohmeyer K. Strategic planning for research use in nursing practice. J Nurs Adm. 1999; 29( 12): 38- 45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lizarondo L, Grimmer-Somers K, & Kumar S. A systematic review of the individual determinants of research evidence use in allied health. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2011; 4: 261- 272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Patel PC, Panzera A, DeNigris J, Dunn R, Chabot J, & Conners S. Evidence-based practice and a nursing journal club: an equation for positive patient outcomes and nursing empowerment. J Nurses Staff Dev. 2011; 27( 5): 227- 230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Luby M, Riley JK, & Towne G. Nursing research journal clubs: bridging the gap between practice and research. Medsurg Nurs. 2006; 15( 2): 100- 102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hart P, Eaton L, & Buckner M. Effectiveness of a computer-based educational program on nurses’ knowledge, attitude, and skill level related to evidence-based practice. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2008; 5( 2): 75- 84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fruth SJ, van Veld RD, Despos CA, Martin RD, Hecker A, & Sincroft EE. The influence of a topic-specific, research-based presentation on physical therapists’ beliefs and practices regarding evidence-based practice. Physiother Theory Pract. 2010; 26( 8): 537- 557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Scurlock-Evans L, Upton P, & Upton D. Evidence-based practice in physiotherapy: a systematic review of barriers, enablers and interventions. Physiotherapy. 2014; 100( 3): 208- 219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Levin RF, Fineout-Overholt E, Melnyk BM, Barnes M, & Vetter MJ. Fostering evidence-based practice to improve nurse and cost outcomes in a community health setting: a pilot test of the advancing research and clinical practice through close collaboration model. Nurs Adm Q. 2011; 35( 1): 21- 33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Morgan LA. A mentoring model for evidence-based practice in a community hospital. J Nurses Staff Dev. 2012; 28( 5): 233- 237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stevenson K, Lewis M, & Hay E. Does physiotherapy management of low back pain change as a result of an evidence-based educational programme. J Eval Clin Pract. 2006; 12( 3): 365- 375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schreiber J, Stern P, Marchetti G, & Provident I. Strategies to promote evidence-based practice in pediatric physical therapy: a formative evaluation pilot project. Phys Ther. 2009; 89( 9): 918- 933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Grimshaw JM, & Eccles MP. Is evidence-based implementation of evidence-based care possible? Med J Aust. 2004; 180( suppl 6): S50- S51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, Hill SJ, & Squires JE. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci. 2012; 7: 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Straus SE, Brouwers M, & Johnson D. Core competencies in the science and practice of knowledge translation: description of a Canadian strategic training initiative. Implement Sci. 2011; 6: 127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]