Abstract

Insect circadian rhythms are generated by a circadian clock consisting of transcriptional/translational feedback loops, in which CYCLE and CLOCK are the key elements in activating the transcription of various clock genes such as timeless (tim) and period (per). Although the transcriptional regulation of Clock (Clk) has been profoundly studied, little is known about the regulation of cycle (cyc). Here, we identify the orphan nuclear receptor genes HR3 and E75, which are orthologs of mammalian clock genes, Rorα and Rev-erbα, respectively, as factors involved in the rhythmic expression of the cyc gene in a primitive insect, the firebrat Thermobia domestica. Our results show that HR3 and E75 are rhythmically expressed, and their normal, rhythmic expression is required for the persistence of locomotor rhythms. Their RNAi considerably altered the rhythmic transcription of not only cyc but also tim. Surprisingly, the RNAi of HR3 revealed the rhythmic expression of Clk, suggesting that this ancestral insect species possesses the mechanisms for rhythmic expression of both cyc and Clk genes. When either HR3 or E75 was knocked down, tim, cyc, and Clk or tim and cyc, respectively, oscillated in phase, suggesting that the two genes play an important role in the regulation of the phase relationship among the clock genes. Interestingly, HR3 and E75 were also found to be involved in the regulation of ecdysis, suggesting that they interconnect the circadian clock and developmental processes.

Introduction

Circadian clocks provide an adaptive advantage by coordinating physiological, behavioral, and biochemical events to occur at an appropriate time of the day [1]. The clock is believed to consist of transcriptional/translational feedback loops. In the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, molecular biological studies have shown that the transcriptional activators CLOCK (CLK) and CYCLE (CYC) heterodimerize and bind to the E-box within the promoters of the per and tim genes to activate their transcription [2]–[4]. PER and TIM proteins accumulate and, subsequently, associate with the CLK/CYC complex to repress their own transcription, forming an about 24-h period feedback loop for the rhythmic expression of per and tim. In addition, the transcription of Clk is also under circadian regulation [5], [6]. It is controlled by cyclical and reciprocal activities of the basic leucine zipper transcription factors VRILLE (VRI) and PAR DOMAIN PROTEIN 1ε (PDP1ε). Both VRI and PDP1ε competitively bind to the VRI/PDP1ε binding site (V/P-box) within the Clk promoter to repress or activate transcription, respectively [7]. Mutations in vri and Pdp1ε affect locomotor activity rhythms, as well as the CLK expression levels [6], [8]. The expression of vri and Pdp1ε is under circadian control, which requires CLK/CYC, thereby connecting the PER/TIM and VRI/PDP1ε feedback loops.

The firebrat Thermobia domestica also possesses a circadian clock based on the rhythmic expression of tim under the control of Clk and cyc [9], [10]. However, unlike Drosophila, cyc, but not Clk, was rhythmically expressed in both light–dark cycles (LD) and constant darkness (DD) [9]. Similar patterns of cyc and Clk expression have been reported for Gryllus bimaculatus and Apis mellifera [11]–[13]. While a large body of genetic and biochemical evidence has been accumulated on the regulation of per, tim, and Clk expressions, little is known about the control of cyc. In the mammalian clock, the cyc ortholog Bmal1 is cyclically expressed, and the underlying mechanism has been extensively studied. Two nuclear receptors, RORα and REV-ERBα, are known to be involved in the mechanism. They directly regulate the expression of Bmal1 by binding to a specific ROR/REV-ERB response element in the Bmal1 promoter region [14]. RORα stimulates Bmal1 transcription, whereas REV-ERBα represses it [15], [16]. Therefore, we expected that cyc might be regulated by a mechanism similar to that found in mammals.

In this study, by taking advantage of the efficacy of RNAi, we investigated the role of probable nuclear hormone receptor 3 gene (HR3), a Ror ortholog, and ecdysone induced protein 75 gene (E75), a Rev-erb ortholog, for the first time in the insect circadian clock by using the firebrat, one of the most primitive insect species. Surprisingly, the gene silencing of HR3 by RNAi revealed the rhythmic expression of Clk, suggesting that this ancestral insect possesses a mechanism for the rhythmic expression of both cyc and Clk genes. The RNAi of HR3 and E75 disrupted the expression levels and phase relationship of the clock genes, leading to a loss of the locomotor activity rhythm. HR3 and E75 were also found to be involved in the regulation of ecdysis. Based on the obtained results, we propose a unique clock model for this ancestral insect.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Adult firebrats, Thermobia domestica, were used for all experiments. They were taken from our laboratory culture reared under a light cycle of 12-h light and 12-h dark conditions (LD 12∶12) at a constant temperature of 30°C. They were fed laboratory chow (CA-1, Clea Japan, Tokyo).

cDNA cloning of HR3 and E75

Total RNA was extracted with the TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) from 5 adult firebrats collected at zeitgeber time (ZT) 10 (ZT0 corresponds to light on and ZT12 to light off). A 5 µg of total RNA was used for reverse transcription to obtain cDNA, using SuperScript III (Invitrogen). Using the obtained cDNA as a template, we performed PCR with degenerate primers deduced from the conserved amino acid sequences among insect HR3 and E75 homologs (Table 1). The amplified fragments were cloned into T-Vector pMD20 (Takara, Ohtsu, Japan) and sequenced with the BigDye Terminator v.3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The 5′ and 3′ RACEs were performed with the GeneRacer Kit (Invitrogen) and SMARTer RACE cDNA Amplification Kit (Takara), respectively, using Blend Taq Plus (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) with gene-specific primers as follows: 5′-TTCCTCGGGCACTGATAGTT-3′ for 5′RACE, and 5′-CGAGGTTCGGTTTCACAGAG-3′ for 3′RACE of HR3, and 5′-GACGCCTGCTTTGAGAAGAG-3′ for 5′RACE, and 5′-AAGCTGGACTCGCCTAATGA-3′ for 3′RACE of E75. RACE fragments were purified, cloned, and sequenced as mentioned above. Sequences were analyzed by Genetyx v.6 (Genetic Information Processing Software, Tokyo, Japan) and BioEdit v.7.0.9.0 (Biological Sequence Alignment Editor, Ibis Therapeutic, Carlsbad, CA). Amino acid sequences of HR3 and E75 were analyzed, and a neighbor-joining tree was inferred with ClustalW (http://clustalw.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/). Known sequences of insects were obtained from GenBank.

Table 1. PCR primers used for PCR, quantitative RT-PCR, and dsRNA synthesis.

| Genes | Forward | Reverse |

| Degenerate PCR | ||

| HR3 | 5′-ccagtcctccgtggtgaaYtaYcaRtg-3′ | 5′-cggggaccatcttggcRaaYtcDat-3′ |

| E75 | 5′-cgcatcctggccgcNatgcaRca-3′ | 5′-acttcttgtggggcttgtaggYYtcRtccat-3′ |

| Quantitative RT-PCR | ||

| HR3 | 5′-CGAGGTTCGGTTTCACAGAG-3′ | 5′-GAGGAGGACGGTTGTTGTTG-3′ |

| E75 | 5′-GAAATGCCCAGCTACACCAC-3′ | 5′-GAACTCAACAACCCCACGAA-3′ |

| Timeless | 5′-TACAAGCCAGGTCCATCACA-3′ | 5′-TCAAGCGTCAATTCAGCATC-3′ |

| Clock | 5′-ATCGCAAGGGTCTGGAAGTG-3′ | 5′-GGAAAACTCGCCAAGACAGG-3′ |

| Cycle | 5′-CGTGTAATCTGTCGTGTTTGGTG-3′ | 5′-GAATCGTCCGCCTTTCCTC-3′ |

| rp49 | 5′-AGTCCGAAGGCGGTTTAAGG-3′ | 5′-TACAGCGTGTGCGATCTCTG-3′ |

| dsRNA synthesis | ||

| HR3#1 | 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGACTTCTCCTGCCTCGGGTAT-3′ | 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCAGTTTTAGCTCCGCCAAAC-3′ |

| HR3#2 | 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCGAAAATGGTACCTGGCTTT-3′ | 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTCGCTTGAATTTACCCAAGG-3′ |

| E75#1 | 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGTCAAAGTCACCCCGAGAA-3′ | 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTCATTAGGCGAGTCCAGCTT-3′ |

| E75#2 | 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCAGAACCAATGGTGGTTTCC-3′ | 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGCCGCTGTTGTTGTAGAGGT-3′ |

| timeless | 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTGCATTTGGTTGTGACTGCT-3′ | 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGAGGCGTGTGCCTTGTACT-3′ |

| Clock | 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGACCACCAATCGAAAAATGGA-3′ | 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCCCAGTTCCCACGAAAACTA-3′ |

| cycle | 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGGGGCTGTTCATTCCTACA-3′ | 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCGCCCACGACTTCAAATAAC-3′ |

| DsRed2 | 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTCATCACCGAGTTCATGCG-3′ | 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCTACAGGAACAGGTGGTGGC-3′ |

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR

Quantitative reverse-transcription PCR (qPCR) was used to measure mRNA levels. Total RNA extraction from adult firebrats was performed using the TRIzol Reagent, and the obtained RNA was treated with DNase I to remove contaminating DNA. Approximately 500 ng of total RNA of each sample was reverse transcribed with random 6mers using the PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (Takara). Real-time PCR was performed with the Mx3000P Real-Time PCR System (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) using the Universal SYBR Green Master (Roche, Tokyo, Japan), including SYBR Green with primers for HR3, E75, tim (GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ Accession No. AB644410), Clk (AB550828), cyc (AB550829), and rp49 (AB550830) (Table 1). In all cases, a single expected amplicon was confirmed by melting analysis. The results were analyzed using the software associated with the instrument. The quantification of mRNA levels was performed by the standard curve method, and the values were normalized with those for rp49, a housekeeping gene, at each time point. Results of 3–4 independent experiments were pooled to calculate the mean ± SEM. Data were analyzed by t-test or ANOVA.

RNA interference

Double-stranded RNAs (dsRNA) for HR3, E75, tim, Clk, and cyc were synthesized using the MEGAscript High Yield Transcription Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) as described previously [10]. DsRed2 derived from a coral species (Discosoma sp.) was used for negative control because the firebrat does not possess the gene; its dsRNA was synthesized in the same procedure. Primers fused with the T7 promoter sequence were designed for synthesizing the dsRNAs (Table 1). The dsRNA solution was stored at −80°C until use. A total of 69 nl (10 µM) of the dsRNA solution was injected using the Nanoliter Injector (WPI, Sarasota, FL) into the abdomen of adult firebrats anesthetized with CO2. The injected amount of dsRNA solution corresponded to 10.23–13.95 µg/g (body weight). The total RNA was extracted from the whole body 1 week after the injection when the effect of the RNA was expected to reach its maximal potential [17].

Recording of locomotor activity

To monitor locomotor activity, adult firebrats were individually housed in transparent acrylic rectangular tubes (6×6×70 mm) as previously described [10]. The raw data were displayed as conventional double-plotted actograms to judge the activity patterns and existence of the rhythmicity, and free-running periods were analyzed by the Lomb-Scargle periodogram by using actogramJ [18], [19]. If the peak of the periodogram appeared above the 0.05 confidence level, then the period of the peak was designated as statistically significant.

Hormonal treatment

20 hydroxyecdysone (20E) (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in 100% EtOH (0.5 mg/ml) and 69 nl (34.5 ng) was injected into the abdomen of adult firebrats anesthetized with CO2. The control was treated with an equivalent amount of 100% EtOH. The total RNA from whole body was isolated at 1week after the injection to measure the mRNA levels of HR3 and E75.

Results

Cloning and sequencing of HR3 and E75 cDNA

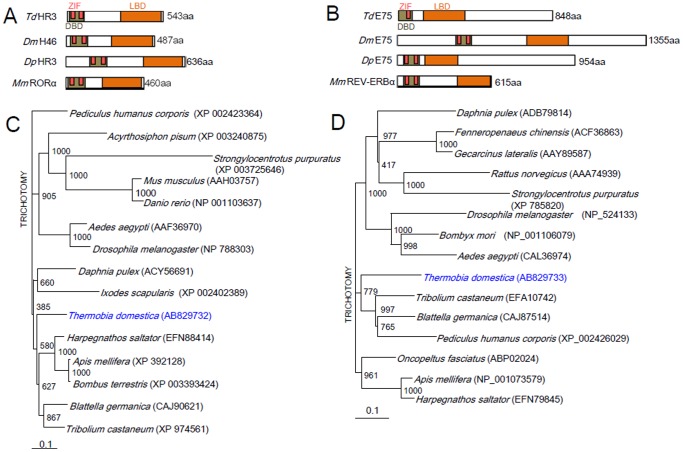

The cDNAs of the nuclear receptors HR3 and E75 were obtained from T. domestica (GenBank Accession Nos. AB829732 for HR3 and AB829733 for E75). The T. domestica HR3 (Td'HR3) and Td'E75 cDNAs encode proteins of 543 and 848 aa residues, respectively, and have 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions (UTR) of 61 and 228 bp, and 98 and 102 bp, respectively. Fig. 1 shows the alignment of the obtained amino acid sequences of Td'HR3 and Td'E75 with those of several other species. Td'HR3 shares 74% sequence identity with Tribolium castaneum HR3 (Tc'HR3). Its DNA-binding domain (DBD) contains two zinc fingers that share 95–100% identity with the HR3 orthologs from other species (Table 2). The ligand-binding domain (LBD) shared 61–83% identity with those of other insects' HR3 orthologs. Td'E75 shared 45–61% identity with other insects' E75 orthologs and its DBD and LBD were nearly 100% and 69–88% identical, respectively, to those of the E75 orthologs. The DBD was equipped with a zinc finger motif, which shares 100% identity (Fig. 1B; Table 2). These are the first HR3 and E75 orthologs in Thysanura insects.

Figure 1. Sequence alignments of conserved domains and phylogenetic neighbor-joining tree of HR3 and E75.

(A, B) Schematic structure of various HR3 (A) or E75 (B) proteins, comparing the organization of the 3 conserved domains, DNA-binding domain (DBD), zinc finger domain (ZIF), and ligand binding domain (LBD). The numbers on the right indicate the number of amino acid residues. Td, Thermobia domestica; Dm, Drosophila melanogaster; Dp, Danaus plexippus; Mm, Mus musculus. (C, D) A phylogenetic neighbor-joining tree of known animal HR3 or E75 proteins. The GenBank or RefSeq accession numbers are indicated in brackets. A reference bar indicates distance as the number of amino acid substitutions per site.

Table 2. Overall amino acid identity and similarity (%) of whole sequence and functional domains of Td'HR3 and Td'E75 with their insect homologs.

| Species | Identity | Similarity | Identity | |||

| DBD | Zinc Finger 1 | Zinc Finger 2 | LBD | |||

| HR3 | ||||||

| Daphnia pulex | 65 | 73 | 97 | 100 | 95 | 78 |

| Drosophila melanogaster | 61 | 76 | 97 | 100 | 95 | 61 |

| Pediculus humanus corporis | 66 | 74 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 83 |

| Tribolium castaneum | 74 | 84 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 83 |

| E75 | ||||||

| Daphnia pulex | 55 | 68 | 100 | - | 100 | 77 |

| Drosophila melanogaster | 49 | 61 | 100 | - | 100 | 69 |

| Pediculus humanus corporis | 55 | 65 | 100 | - | - | 87 |

| Tribolium castaneum | 61 | 68 | 100 | - | 100 | 88 |

DBD, DNA-binding domain; LBD, ligand-binding domain.

A phylogenetic tree based on the amino acid sequences of HR3 and E75 from known insects, sea urchins, and some vertebrates revealed three clusters of HR3 and E75. Td'HR3 formed a cluster with the beetle Tribolium castaneum, the cockroach Blattella germanica, the honeybee Apis mellifera, the bumble bee Bombus terrestris, and the ant Harpegnathos saltator, while Td'E75 with the beetle Tribolium castaneum, the cockroach Blattella germanica, and the louse Pediculus humanus corporis (Fig. 1).

Temporal expression patterns of Td'HR3 and Td'E75 mRNA

To determine whether the transcripts of Td'HR3 and Td'E75 oscillated in a circadian manner, we measured the levels of their mRNA under LD 12∶12 and on the 2nd day of DD by using qPCR (Fig. 2). In LD, both Td'HR3 and Td'E75 mRNAs were rhythmically expressed, peaking at late day or early night (ANOVA, P<0.03, S1 Table). Their rhythmic expressions persisted in DD (ANOVA, P<0.05, S1 Table), thus, suggesting their circadian control.

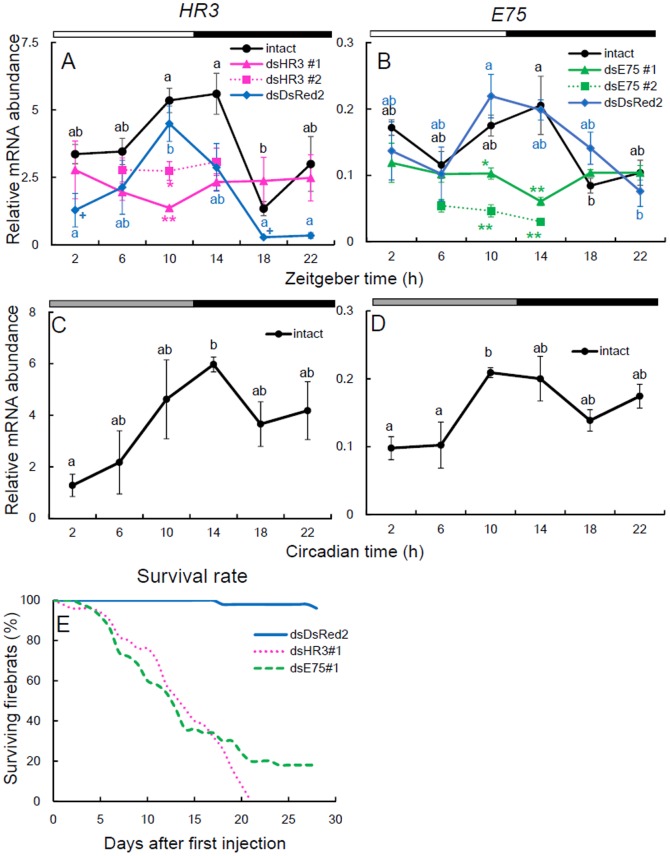

Figure 2. Expression profiles of Td'HR3 and Td'E75 mRNA and effects of their dsRNAs on their mRNA levels and the survival rate in firebrats.

Both Td'HR3 (A, C) and Td'E75 (B, D) were rhythmically expressed in LD (A, B) and DD (C, D), peaking late (subjective) day to early (subjective) night (black symbols). DsHR3#1,2 (pink triangles and squares for #1 and #2, respectively) and dsE75#1,2 (green triangles and squares for #1 and #2, respectively) downregulated mRNA levels and disrupted the rhythm of their respective genes (A and B). Treatment with dsDsRed2 as a negative control did not disrupt the rhythmic expression in both genes (A and B, blue symbols), but caused a significant decrease in Td'HR3 mRNA levels at ZT 2 and ZT 18 (+ P<0.05, t test vs intact). White, black, and gray bars above each graph indicate day, night/subjective night, and subjective day, respectively. Total RNA was extracted from firebrats collected at 4-h intervals starting 2 h after lights on or 2 h into subjective day (ZT2 or CT2, respectively). The data collected from 3–4 independent experiments were averaged and plotted as the mean ± SEM values relative to the value of rp49 mRNA used as the reference. Values with different letters significantly differ from each other within the same treatment groups (P<0.05, ANOVA with Tukey test, S1 Table). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, t test vs dsDsRed2 (exact P values are shown in S2 Table). (E) Survival rate after injection of 10.23–13.95 µg/g dsHR3, dsE75, or dsDsRed2 into the abdomen. DsHR3 and dsE75 significantly reduced the survival rate. For further explanation, see text.

RNAi of Td'HR3 and Td'E75

To examine the possible role of Td'HR3 and Td'E75 in the firebrat circadian clock, we examined the effectiveness of RNAi on Td'HR3 and Td'E75 one week after the treatment. We first examined the effects of dsRNA of DsRed2 used as negative control. As shown in Fig. 2A, Td'HR3 was slightly reduced but the reduction was not significant at most time points, except for ZT 2 and ZT 18. No significant effect was observed in Td'E75 transcript levels (Fig. 2B).

For RNAi of Td'HR3 and Td'E75, we used two different dsRNAs synthesized for different regions of the two genes (Table 1). The Td'HR3 RNAi and Td'E75 RNAi firebrats showed a high lethality because of ecdysis failure (Fig. 2E); 50% of the treated firebrats died within two weeks. This may be because these genes are involved in the ecdysone-signaling pathway involved in ecdysis. When examined 1 week after dsRNA treatment, the dsRNAs significantly reduced respective mRNAs (Fig. 2A–B, S2 Table) to near or below basal levels of intact firebrats and the levels were maintained throughout the day with no rhythmic changes (ANOVA, P>0.1, S1 Table). Thus, the expression of Td'HR3 and Td'E75 were successfully suppressed through RNAi. The levels of knockdown were similar to those known for Td'Clk and Td'cyc but less than for Td'tim [9], [10].

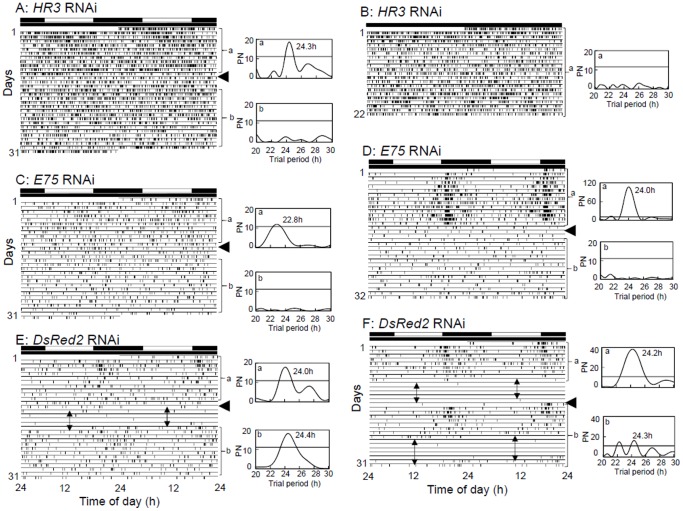

Td'HR3 dsRNA and Td'E75 dsRNA treatments disrupt circadian locomotor activity and ecdysis

In order to examine the role of Td'HR3 and Td'E75 in the regulation of circadian behavioral rhythms, we compared locomotor rhythms between Td'HR3 RNAi and Td'E75 RNAi firebrats and control firebrats with DsRed2 dsRNA injected in LD and DD (Fig. 3). Because Td'HR3 RNAi and Td'E75 RNAi firebrats showed a high lethality (Fig. 2E), we performed analysis of the locomotor activity rhythm only for firebrats survived for more than two weeks after the injection of dsRNA. The results are summarized in Table 3. Most of the DsRed2 RNAi firebrats exhibited a nocturnal rhythm synchronizing to LD and free running in DD with a period of about 24 h (Fig. 3E and F), similar to intact animals [9], [10]. However, the free-running period considerably varied among individuals, showing rather large standard deviation (Table 3). In the Td'HR3 RNAi and Td'E75 RNAi firebrats, 100% (6/6) and 71% (12/17) of animals, respectively, exhibited, under LD, a rhythmic activity synchronized to the LD (Fig. 3A–D; Table 3), and the remaining animals were arrhythmic (Fig. 3B). In the ensuing DD, 75% (6/8) and 100% (4/4) animals for Td'HR3 dsRNA#1 and #2 treatment, respectively, and 78% (7/9) and 83% (5/6) of animals for Td'E75 dsRNA#1 and #2 treatment, respectively, almost immediately became arrhythmic (Fig. 3A–D; Table 3), suggesting that the rhythm observed in LD was a masking effect of the light. Interestingly, none of Td'HR3 and Td'E75 RNAi firebrats showed ecdysis. Thus, the interruption of the locomotor activity associated with ecdysis was not observed (Fig. 3A–D).

Figure 3. Effects of HR3 and E75 dsRNA on locomotor rhythms in the firebrat.

Double-plotted actograms (left) and Lomb-Scargle periodograms (right) of locomotor rhythms under LD 12∶12 and DD at a constant temperature of 30°C are shown for firebrats injected with HR3 (A, B) and E75 dsRNA (C, D) or DsRed2 dsRNA (E, F). White and black bars above the actograms indicate light (white) and dark (black) conditions. Arrowheads indicate the day when the firebrats were transferred from LD to DD. a and b indicated in the periodogram correspond to the analyzed time span, a and b, indicated in the actogram, respectively. An oblique line in the periodogram indicates a significance level of P<0.05; a peak value above the line was designated as significant. (A–D) Some of the HR3 and E75 RNAi firebrats showed a rhythm in LD, which disappeared upon transfer to DD. (E, F) Control firebrats injected with DsRed2 dsRNA showed a significant rhythm throughout the recording period. No activity was recorded during the period indicated by double headed arrows because of molting. For further explanation, see text.

Table 3. Effects of dsHR3, dsE75, and dsDsRed2 on the locomotor rhythm of the firebrat Thermobia domestica.

| Treatment | n | No. of insects | Free-running period (mean ± SD) h | |

| Rhythmic (%) | Arrhythmic (%) | |||

| LD | ||||

| HR3 dsRNA#1 | 6 | 6 (100) | 0 (0) | 24.0±1.6 |

| E75 dsRNA#1 | 17 | 12 (71) | 5 (29) | 23.8±1.0 |

| DsRed2 dsRNA | 20 | 18 (90) | 2 (20) | 23.9±0.3 |

| DD | ||||

| HR3 dsRNA#1 | 8 | 2 (25) | 6 (75)a | 24.2±0,6 |

| HR3 dsRNA #2 | 4 | 0 (0) | 4(100)b | - |

| E75 dsRNA #1 | 9 | 2 (22) | 7 (78)b | 24.5±0.4 |

| E75 dsRNA #2 | 6 | 1 (17) | 5 (83)b | 24.3 |

| DsRed2 dsRNA | 24 | 18 (75) | 6 (25) | 24.1±0.8 |

P<0.05, b P<0.001 vs DsRed2 dsRNA, Chi-square test; SD, standard deviation; LD, light–dark cycle; DD, constant darkness.

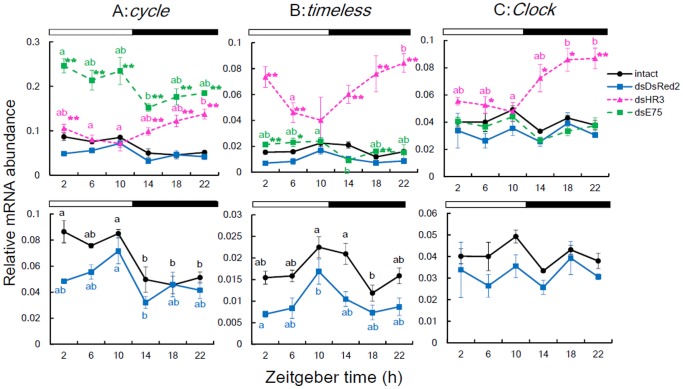

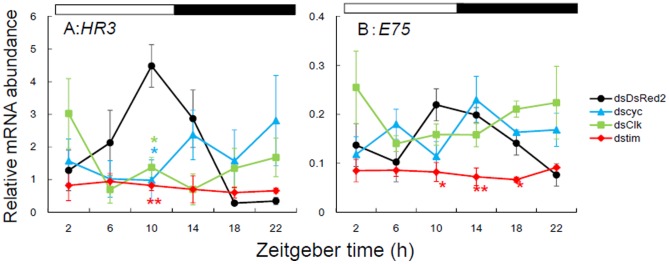

Td'HR3 RNAi and Td'E75 RNAi affect the expression of Td'cyc, Td'tim, and Td'Clk

We next examined whether Td'HR3 and/or Td'E75 were regulators of Td'cyc transcription by measuring the daily expression profiles of Td'cyc mRNA in Td'HR3 RNAi and Td'E75 RNAi firebrats. For this and the following analyses only Td'HR3 dsRNA#1 and Td'E75 dsRNA#1 were used. Td'E75 RNAi upregulated the Td'cyc mRNA level more than three-fold of the negative control but did not alter its rhythmic expression, while Td'HR3 RNAi reversed the phase of the Td'cyc mRNA rhythm, with a gradual increase throughout the night to peak late at night (Fig. 4A, S3 and S4 Tables). These results demonstrate the involvement of Td'HR3 and Td'E75 in the circadian transcriptional regulation of Td'cyc.

Figure 4. Effects of HR3 (dsHR3, pink symbols) and E75 dsRNA (dsE75, green symbols) on mRNA levels of cyc, tim, and Clk in firebrats.

Values for intact and dsDsRed2 injected control are shown in black and blue symbols, respectively, and replotted in lower panels with an expanded ordinate. (A) cyc normally peaked during the day. dsE75 significantly upregulated the mRNA levels, while dsHR3 shifted the rhythm to peak late at night. (B) tim showed a rhythm with a peak at late day or early night in intact firebrats. DsE75 slightly advanced the rhythm while dsHR3 upregulated and shifted the rhythm to peak late at night. (C) Clk showed no significant rhythm in intact firebrats. DsE75 had no significant effect on Clk mRNA levels, while dsHR3 induced a rhythm with a peak at mid–late night. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, t test vs dsDsRed2 (exact P values are shown in S3 Table). Values with different letters significantly differ from each other (p<0.05, ANOVA with Tukey test, S4 Table). For tim in firebrats treated with dsHR3 (B), significant rhythm was confirmed by the single cosinor method [28] and significant difference was found between values at ZT6 and ZT22 (t-test, P<0.05). For further explanation, see text and Fig. 2.

Td'HR3 and Td'E75 RNAi considerably affected the circadian expression of the clock genes Td'tim and Td'Clk. Td'HR3 RNAi upregulated the expression of Td'tim and shifted the rhythms to peak late at night, while Td'E75 RNAi slightly increased the Td'tim mRNA levels to peak during the day (Fig. 4B, S3 and S4 Tables). Surprisingly, Td'HR3 RNAi induced the rhythmic expression of Td'Clk to peak late at night with the upregulation of mRNA levels (Fig. 4C, S3 and S4 Tables), suggesting that the firebrat has a mechanism for the rhythmic expression of Td'Clk, which may be concealed by a mechanism involving Td'HR3. Td'E75 RNAi, however, had no significant effect on Td'Clk mRNA levels (Fig. 4C, S3 Table). Interestingly, in Td'HR3 RNAi firebrats, the rhythms of Td'cyc, Td'tim, and Td'Clk peaked almost in phase late at night, whereas in Td'E75 RNAi firebrats, Td'cyc and Td'tim showed in-phase oscillations and peaked during the day (Fig. 4A–C).

Rhythmic expressions of Td'HR3 and Td'E75 require Td'cyc, Td'tim, and Td'Clk

BMAL1 and CLK have been postulated to be positive regulators of Rorα and Rev-erbα in mammalian clocks [15], [16]. This hypothesis prompted us to examine whether Td'CYC and Td'CLK activate Td'HR3 and Td'E75 transcriptions in the firebrat. Therefore, we measured their daily expression profiles in Td'cyc RNAi and Td'Clk RNAi firebrats. The mRNA levels of Td'HR3 were significantly reduced and its circadian rhythm was abolished in both Td'cyc RNAi and Td'Clk RNAi firebrats (Fig. 5A). However, for Td'E75, its rhythm was disrupted in both dsClk and dscyc treatments but no significant changes were observed in its mRNA levels (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. Effects of cyc, Clk, and tim dsRNA (dscyc, dsClk, and dstim) on mRNA levels of HR3 and E75 in firebrats.

(A) Dscyc, dsClk, and dstim abolished the rhythmic expression of HR3 with significant downregulation of mRNA levels. (B) RNAi of the three genes abolished the rhythm of E75. Dstim effectively downregulated E75 mRNA but dscyc and dsClk had no significant effects, except at ZT18 where a significant increase was observed. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, t test vs dsDsRed2. Data for dsDsRed2 firebrats are replotted from Fig. 2. For further explanation, see text and Fig. 2.

We also performed the same measurement in Td'tim RNAi firebrats because we speculated that the PER/TIM heterodimer, similar to the PER/CRY complex in mammals, may suppress Td'HR3 and Td'E75 transcription indirectly by repressing the transcriptional activity of CYC/CLK. The levels of both Td'HR3 and Td'E75 mRNAs were significantly downregulated and their rhythms were disrupted in Td'tim RNAi firebrats (Fig. 5A, B). This result is inconsistent with the mammalian clock hypothesis but is explained by our earlier finding that Td'tim RNAi downregulates Td'cyc transcript levels [10].

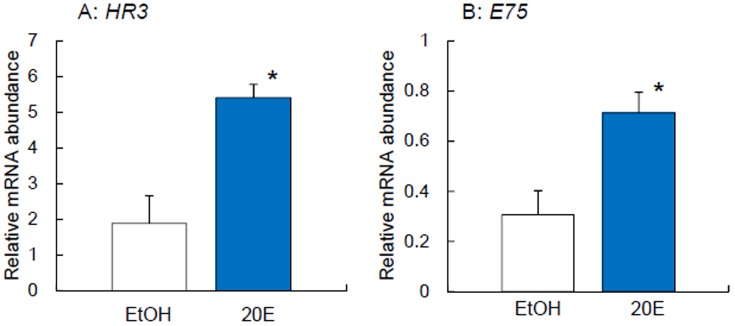

20E upregulates Td'HR3 and Td'E75 transcription

Given that HR3 and E75 genes expression profiles in D. melanogaster strongly correlated with ecdysis [20], we examined the effects of 20E on Td'HR3 and Td'E75 mRNA levels. We injected 34.5 ng of 20E into the abdomen of adult firebrats. Td'HR3 and Td'E75 were evidently upregulated 1 week after 20E injection compared with the control firebrats injected with EtOH (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Effects of ecdysone on mRNA levels of Td'HR3 (A) and Td'E75 (B) in firebrats.

White and blue columns indicate the mRNA levels of EtOH (negative control) and ecdysone injected firebrats, respectively. 100% EtOH (69 nl) or 34.5 ng ecdysone (dissolved in 69 nl of EtOH) was injected and firebrats were collected at ZT 10 (10 h after light on) one week after the injection. The abundance of mRNA was measured by qPCR. The data collected from 4 independent experiments were averaged and plotted as mean ± SEM values relative to the value of rp49 mRNA used as reference.*P<0.05, t-test.

Discussion

The present study revealed that the mRNAs of the nuclear receptor genes Td'HR3 and Td'E75 were rhythmically expressed in both LD and DD, peaking late day to early night (Fig. 2). The rhythmic expression was comparable to their mammalian orthologs, Rorα and Rev-erbα [15], [16]. Since RNAi of Td'cyc and Td'Clk disrupted the daily expression rhythms of Td'HR3 and Td'E75 genes, and downregulated Td'HR3 mRNA levels (Fig. 5), we assume that the rhythmic expression of Td'HR3 and Td'E75 are regulated by Td'CYC and Td'CLK, similar to their mammalian orthologs.

Our results demonstrated that Td'HR3 and Td'E75 are factors involved in the cyclic transcription of Td'cyc in the firebrat. The RNAi experiment showed that Td'E75 may be a repressor of Td'cyc transcription, similar to mammalian REV-ERBα [15], because its RNAi resulted in substantial upregulation of Td'cyc mRNA levels (Fig. 4A). However, Td'HR3 may act as a phase regulator of Td'cyc since its RNAi resulted in a phase reversal in Td'cyc oscillation with an increase of mRNA levels during the night (Fig. 4A). The results also imply that this may occur through another unknown factor(s) that activates the transcription of Td'cyc during the night.

In addition, Td'HR3 might also participate in the regulation of Td'Clk expression, since its RNAi induced a circadian oscillation and an upregulation of Td'Clk mRNA levels (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, Td'cyc, Td'Clk, and Td'tim oscillated in phase to peak around mid–late night in the Td'HR3 RNAi firebrats (Fig. 4A–C). However, in the Td'E75 RNAi firebrats, Td'cyc and Td'tim showed an in-phase oscillation that peaked during the day (Fig. 4A–B), suggesting that Td'E75 regulates the phase of Td'tim. The phase coherence was never observed in intact firebrats; Td'cyc and Td'tim oscillated with differential peaks phased during the day and late day to early night, respectively. Their in-phase oscillation in RNAi firebrats suggests that their transcriptions are regulated by a common factor, and Td'HR3 and Td'E75 play a role as phase regulators to directly or indirectly set the clock gene oscillations in a proper phase relationship. A similar phase coherence was observed in the sandfly Lutzomyia longipalpis, in which Clk and cyc transcripts peaked simultaneously with or slightly earlier than per and tim [21], [22], and in some mammalian peripheral tissues where Bmal1 and Per were expressed almost in phase [23], [24]. This feature is in opposition to the hypotheses of the Drosophila and mammalian central clocks, where peaks of per/tim (Per/Cry) and Clk/cyc (Clk/Bmal1) transcriptions are about 12 h apart from each other [25]. The reason and mechanism underlying the phase coherence should be addressed in future studies.

The behavioral analysis of Td'HR3 RNAi and Td'E75 RNAi firebrats revealed that both genes have two roles. First, they are important for the persistence of locomotor activity rhythms in DD (Fig. 3A–B; Table 3), which is also seen in mice where RORα and REV-ERBα are required for normal daily locomotor activity [15], [16], [26]. The Td'HR3 RNAi or Td'E75 RNAi firebrats showed in-phase oscillations of Td'cyc, Td'tim, and Td'Clk or Td'cyc and Td'tim, respectively (Fig. 4A–C). Nevertheless, they lost the locomotor rhythm in DD (Fig. 3A–B). This result suggests that the persistence of the locomotor rhythm requires a temporally coordinated and/or properly leveled expression of those clock genes in the firebrat. Thus, HR3 and E75 might have been involved as essential components in the ancestral insect clock. In addition, they are known to play important roles within the ecdysone-signaling pathway in Drosophila [20], and this may be true in the firebrat because they were upregulated by 20E (Fig. 6). This hypothesis also explains why a majority of firebrats with Td'HR3 and Td'E75 RNAi died from ecdysis failure (Fig. 2E), although no such failure was observed in the RNAi of other clock- and clock-related genes [9], [10]. Thus, they may couple the developmental processes and circadian rhythms in the firebrat.

The circadian clock machinery has been substantially clarified in Drosophila and mammals. In the current Drosophila clock model, per and tim are rhythmically expressed by the core-feedback loop consisting of transcriptional repressors, PER and TIM, and activators, CYC and CLK [27]. Clk is also rhythmically expressed by a loop, including vri and Pdp1ε [6], [8]. It seems likely that the firebrat's core loop might be operating in a similar way. Td'TIM may have two roles, i.e., repression of the transcriptional activity of Td'CYC and activation of the Td'cyc transcription through some unknown mechanism, because our previous results have shown that Td'tim RNAi downregulates the Td'cyc transcripts [10]. This scheme also explains why Td'tim RNAi downregulated both Td'HR3 and Td'E75 (Fig. 5). In contrast to Drosophila, Td'cyc is rhythmically expressed in the firebrat [9], [10], and our results revealed that the oscillatory mechanism involved Td'HR3 and Td'E75 although the details have yet to be clarified. This property resembles the mammalian clock.

Unexpectedly, Td'HR3 RNAi revealed the rhythmic expression of Td'Clk, suggesting the coexistence of an oscillatory mechanism for Td'Clk. In comparison to the Drosophila circadian clock, we currently hypothesize that the rhythmic transcription of Td'Clk is regulated by VRI and PDP1ε. In many insects, cyc but not Clk, has been shown to be rhythmically expressed. However, our data suggest that, even in those species, the mechanism for the cyclic expression of Clk might be retained but concealed in normal physiological conditions. In fact, we have recently shown that Clk is rhythmically expressed when cyc is knocked down in the cricket G. bimaculatus [12]. Interestingly, both Clk and cyc are expressed in a rhythmic manner in the sandflies [21], [22]. Together with these facts, our results suggest that an ancestral insect clock has mechanisms for the rhythmic expression of both cyc and Clk but have diversified to express either or both of them during the course of adaptation to specific environments. Further comparative studies are necessary to test this view.

Supporting Information

Results of one way ANOVA for daily changes of mRNA levels of HR3 and E75 in intact firebrats and those treated with dsRNAs of DsRed2 , HR3 and E75 .

(PDF)

P values of t -test between HR3 or E75 mRNA levels of firebrats treated with ds HR3 or ds E75 and those treated with ds DsRed2 .

(PDF)

P values of t-test between firebrats treated with ds HR3 or ds E75 and those treated with ds DsRed2 .

(PDF)

Results of one way ANOVA for daily changes in mRNA levels of timeless , cycle and Clock genes in intact firebrats and those treated with dsRNAs of DsRed2 , HR3 and E75 .

(PDF)

Data Availability

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by grants from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) to KT (No. 23370033) and KY (No. 23-6445). KY and OU were JSPS Research Fellows. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Pittendrigh CS, Minis DH (1971) The photoperiodic time measurement in Pectionphora gossypiella and its relation to the circadian system in that species. In: Menaker M, editor. Biochronometry. Washington D.C.: National Academy of Science. pp.212–250. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stanewsky R (2002) Clock mechanisms in Drosophila . Cell and Tissue Research 309:11–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dunlap JC (1999) Molecular bases for circadian biological clocks. Cell 96:271–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tomioka K, Matsumoto A (2010) A comparative view of insect circadian clocks. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 67:1397–1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Allada R, White NE, So WV, Hall JC, Rosbash M (1998) A mutant Drosophila homolog of mammalian Clock disrupts circadian rhythms and transcription of period and timeless . Cell 93:791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cyran SA, Buchsbaum AM, Reddy KL, Lin M-C, Glossop NRJ, et al. (2003) vrille, Pdp1 and dClock form a second feedback loop in the Drosophila circadian clock. Cell 112:329–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hardin P (2005) The circadian timekeeping system of Drosophila . Current Biology 15:R714–R722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Blau J, Young MW (1999) Cycling vrille Expression Is Required for a Functional Drosophila Clock. Cell 99:661–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kamae Y, Tanaka F, Tomioka K (2010) Molecular cloning and functional analysis of the clock genes, Clock and cycle, in the firebrat Thermobia domestica . Journal of Insect Physiology 56:1291–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kamae Y, Tomioka K (2012) timeless is an essential component of the circadian clock in a primitive insect, the firebrat Thermobia domestica . Journal of Biological Rhythms 27:126–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rubin EB, Shemesh Y, Cohen M, Elgavish S, Robertson HM, et al. (2006) Molecular and phylogenetic analyses reveal mammalian-like clockwork in the honey bee (Apis mellifera) and shed new light on the molecular evolution of the circadian clock. Genome Research 16:1352–1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Uryu O, Karpova SG, Tomioka K (2013) The clock gene cycle plays an important role in the circadian clock of the cricket Gryllus bimaculatus . Journal of Insect Physiology 59:697–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moriyama Y, Kamae Y, Uryu O, Tomioka K (2012) Gb'Clock is expressed in the optic lobe and required for the circadian clock in the cricket Gryllus bimaculatus . Journal of Biological Rhythms 27:467–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guillaumond F, Dardente H, Giguere V, Cermakian N (2005) Differential control of Bmal1 circadian transcription by REV-ERB and ROR nuclear receptors. Journal of Biological Rhythms 20:391–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Preitner N, Damiola F, Lopez-Molina L, Zakany J, Duboule D, et al. (2002) The orphan nuclear receptor REV-ERBa controls circadian transcription within the positive limb of the mammalian circadian oscillator. Cell 110:251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sato TK, Panda S, Miraglia LJ, Reyes TM, Rudic RD, et al. (2004) A functional genomics strategy reveals Rora as a component of the mammalian circadian clock. Neuron 43:527–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Uryu O, Kamae Y, Tomioka K, Yoshii T (2013) Long-term effect of systemic RNA interference on circadian clock genes in hemimetabolous insects. Journal of Insect Physiology 59:494–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sokolove PG, Bushell WN (1978) The chi square periodogram: its utility for analysis of circadian rhythm. Journal of Theoretical Biology 72:131–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schmid B, Helfrich-Förster C, Yoshii T (2011) A new ImageJ plug-in “ActogramJ”. for chronobiological analyses Journal of Biological Rhythms 26:464–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ruaud AF, Lam G, Thummel CS (2010) The Drosophila nuclear receptors DHR3 and βFTZ-F1 control overlapping developmental responses in late embryos. Development 137:123–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Meireles-Filho ACA, Rivas GBS, Gesto JSM, Machado RC, Britto C, et al. (2006) The biological clock of an hematophagous insect: locomotor activity rhythms, circadian expression and downregulation after a blood meal. FEBS Letters 580:2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Meireles-Filho ACA, Amoretty PR, Souza NA, Kyriacou CP, Peixoto AA (2006) Rhythmic expression of the cycle gene in a hematophagous insect vector. BMC Molecular Biology 7:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bebas P, Goodall CP, Majewska M, Neumann A, Giebultowicz JM, et al. (2009) Circadian clock and output genes are rhythmically expressed in extratesticular ducts and accessory organs of mice. The FASEB Journal 23:523–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tong Y, Guo H, Brewer JM, Lee H, Lehman MN, et al. (2004) Expression of haPer1 and haBmal1 in Syrian hamsters: heterogeneity of transcripts and oscillations in the periphery. Journal of Biological Rhythms 19:113–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hardin P (2009) Molecular mechanisms of circadian timekeeping in Drosophila . Sleep and Biological Rhythms 7:235–242. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bugge A, Feng D, Everett LJ, Briggs ER, Mullican SE, et al. (2012) Rev-erbα and Rev-erbβ coordinately protect the circadian clock and normal metabolic function. Genes & Development 26:657–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Allada R, Kadener S, Nandakumar N, Rosbash M (2003) A recessive mutant of Drosophila Clock revels a role in circadian rhythm amplitude. EMBO Journal 22:3367–3375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nelson W, Tong Y, Lee J, Halberg F (1979) Methods for cosinor-rhythmometry Chronobiologia 6: 305–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Results of one way ANOVA for daily changes of mRNA levels of HR3 and E75 in intact firebrats and those treated with dsRNAs of DsRed2 , HR3 and E75 .

(PDF)

P values of t -test between HR3 or E75 mRNA levels of firebrats treated with ds HR3 or ds E75 and those treated with ds DsRed2 .

(PDF)

P values of t-test between firebrats treated with ds HR3 or ds E75 and those treated with ds DsRed2 .

(PDF)

Results of one way ANOVA for daily changes in mRNA levels of timeless , cycle and Clock genes in intact firebrats and those treated with dsRNAs of DsRed2 , HR3 and E75 .

(PDF)

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper.