Abstract

A 40-year-old woman from India presented with a mass in the front of her left knee which had been present for 8 months. Local examination revealed a globular mass of approximate size 5 cm × 4 cm × 4 cm in front of the lower pole of left patella. The patient was investigated with imaging studies and laboratory tests. Plain radiograph of the chest was normal. In addition, contrast enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the left knee was performed. Based on the history, physical examination, laboratory and imaging studies, what is the differential diagnosis?

Keywords: Prepatellar mass, Excisional biopsy, Synovial sarcoma

1. History and physical examination

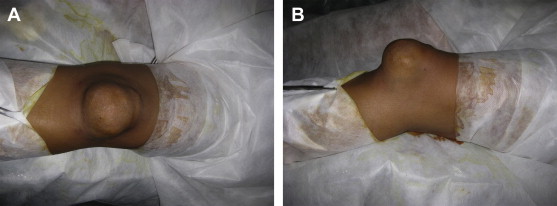

A 40-year-old woman from India presented with a mass in the front of her left knee which had been present for 8 months (Fig. 1A). The mass was insidious in onset and gradually progressive in size. She described that it was initially about the size of a grape that increased to about the size of a lemon at the time of presentation. It was localized to the front of the lower half of patella. She reported mild discomfort after exertion; however, denied true pain. There was no history of sudden increase in the size of mass or episodes of increased pain. There were no symptoms of instability or locking of the knee. There was no history of fever, weight loss, anorexia, hemoptysis, pruritus, seizures, or similar mass elsewhere in the body. It was not associated with any preceding history of trauma. Her family history was non-contributory. The patient used to do the household work (like mopping the floor) that involved prolonged kneeling. The patient initially suspected the mass was related to prolong kneeling to do housework, but presented to her primary care physician as the mass became so large. Subsequently, she was referred to our hospital for further treatment.

Fig. 1.

A–B: (A) Clinical photograph of the patient as viewed from the anterior aspect (B) as viewed from the side.

On examination, the vitals were stable and there was no evidence of lymphadenopathy. Her physical status was good. Local examination revealed a globular mass of approximate size 5 cm × 4 cm × 4 cm in front of the lower pole of left patella (Fig. 1B). The overlying skin was normal. It was mildly tender and local temperature was comparable to other body parts. The overlying skin was freely mobile and there were no scars or sinuses. The mass was not fixed to underlying tissues. Its margins were well defined as these could be palpated separate from the underlying patella. It was firm in consistency. It was not compressible, and nonfluctuant. The mass could not be transilluminated. It became more prominent when the knee was extended against resistance. There was no effusion in the knee. No functional impairment was observed at the knee. Distal neurovascular status of the limb was normal. The remaining organ systems (respiratory system, abdomen, nervous system) appeared normal on clinical examination.

The patient was investigated with imaging studies and laboratory tests. Plain radiograph of the chest was normal. In addition, contrast enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the left knee was performed.

Based on the history, physical examination, laboratory and imaging studies, what is the differential diagnosis?

2. Imaging interpretation

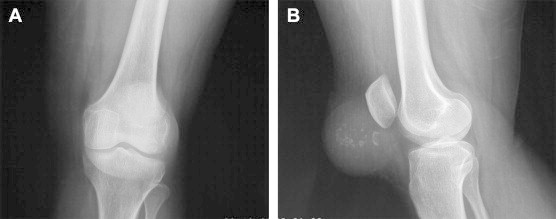

Anteroposterior (Fig. 2A) and lateral view (Fig. 2B) radiographs of the left knee were obtained which revealed large, globular soft tissue shadow in the prepatellar region. Lateral view revealed multiple, coarse calcification within the mass (Fig. 2B). The underlying patella and other osseous structures (femur and tibia) were normal in appearance.

Fig. 2.

A–B: (A) Anteroposterior view of the involved knee showing double shadow of the soft tissue in the region of patella and distal femur (B) lateral view radiograph showing round soft tissue shadow in front of patella along with areas of calcification within it.

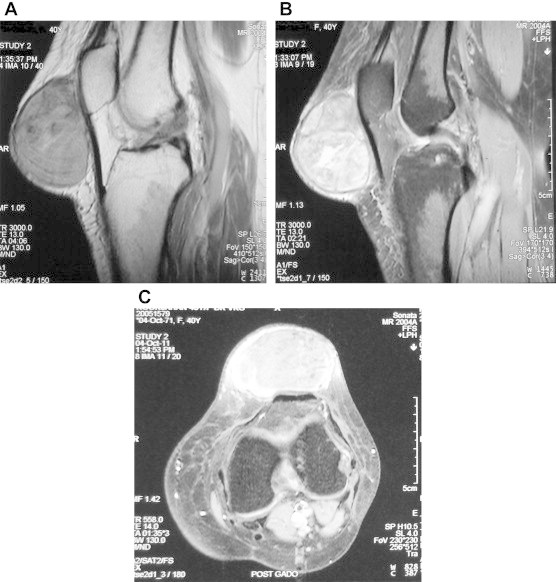

Multi-sequence MRI demonstrated a well-defined, globular, septate mass anterior to the lower pole of patella, which measured 5.6 cm × 4 cm × 5.4 cm in the greatest dimensions. It displayed altered signal intensity appearing heterogeneously iso-to hypointense on T1W images (Fig. 3A) and iso-to hyperintense on T2W images (Fig. 3B). The mass was seen abutting the prepatellar fat and patellar tendon. Images acquired following administration of intravenous Gadolinium contrast revealed heterogenous contrast enhancement. Periphery of the mass revealed some contrast enhancement (Fig. 3C). There was no evidence of hemorrhage or necrosis.

Fig. 3.

A–C: (A) T1-weighted magnetic resonance image (sagittal view) showing well defined, globular, septated mass in front of the lower pole of patella which measured 5.6 cm × 4 cm × 5.4 cm in the greatest dimensions. It displayed altered signal intensity appearing heterogeneously hypointense on T1W images (B) T2-weighted magnetic resonance image (sagittal view) showing iso-to hyperintense signal intensity of the mass (C) Axial images acquired following administration of intravenous Gadolinium agent showing heterogenous contrast enhancement especially at the periphery of the lesion. However, surrounding osseous structures appear normal.

Laboratory examination revealed total leukocyte count (11,800/cumm) and differential count was polymorphs 65, lymphocytes 33, monocytes 1, eosinophils 1. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (35 mm at the end of first hour) was raised; however C-reactive protein (3.9 mg/l) level was within normal limits. The sputum examination was negative for acid fast bacilli. ELISA test for HIV I & II antibody was negative. The patient's immune status was normal with no other focus of infection.

3. Differential diagnosis

Tenosynovial giant cell tumor (solitary pigmented villonodular synovitis)

Chronic prepatellar bursitis

Fibromatosis

Chronic granulomatous infection (tuberculosis)

Hemangioma

Malignant neoplasm (synovial sarcoma/malignant fibrous histiocytoma/liposarcoma)

A fine needle aspiration under image guidance was attempted twice but yielded no diagnostic material both the times. The patient underwent wide local excision under regional anesthesia. The mass was excised en-bloc along with the overlying pseudocapsule, normal cuff of surrounding tissues and the redundant skin (Fig. 4A). It measured 5.5 cm × 4 cm × 5 cm and had firm consistency. The periosteum of underlying patella and sheath of patellar tendon were also excised along with the mass over the posterior aspect (Fig. 4B). After completing the procedure, the mass was cut open longitudinally from the posterior surface which showed a well circumscribed, trilobulated, yellowish white firm cut surface (Fig. 4C). Macroscopically, the areas of hemorrhage or necrosis were not seen. Gritty sensation was appreciated while cutting the mass. The entire tissue was submitted for histopathological examination and culture. Based on the clinical history, physical examination, radiographic images, and histopathological examination, what is the diagnosis and how should the lesion be treated?

Fig. 4.

A–C: (A) Resected specimen of mass (size; 5.5 cm × 4 cm × 5 cm) with overlying redundant skin, pseudocapsule, and a margin of healthy tissue (B) The posterior surface of the specimen along with pseudocapsule and periosteum of patella and sheath of patellar tendon (C) The cut surface of the mass (cut open from the posterior surface) showing a well circumscribed, trilobulated, yellowish white fibrous structure without macroscopic areas of hemorrhage or necrosis.

4. Histopathologic interpretation

The histopathological examination revealed an encapsulated tumor showing lobulated architecture (Fig. 5A). Tumor showed hypo and hypercellular areas with perivascular condensation of tumor cells (Fig. 5B). It showed the areas of myxoid change (Fig. 5C) and focal necrosis. The tumor was composed of plump spindle shaped cells with moderate pleomorphism and high mitotic activity (Fig. 5D). Focal areas of metaplastic bone formation were present surrounded by tumor cells. It did not show any definite area of capsular breach (Fig. 5A). Overlying skin was also free from tumor infiltration. Immunohistochemical analysis showed positive results for vimentin, smooth muscle actin, S100, keratin, and neurone specific enolase. The features were consistent with synovial sarcoma.

Fig. 5.

A–D: (A) A scanner-view photomicrograph (Stain, hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification, ×40) showing the tumor with fibrous capsule. No definitive area of breach was seen. (B) Low-power photomicrograph (Stain, hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification, ×100) showing hypo and hypercellular areas with perivascular condensation of tumor cells (C) Low-power photomicrograph (Stain, hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification, ×100) showing myxoid changes in the tumor (D) High-power photomicrograph (Stain, hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification, ×400) showing the tumor composed of plump spindle cells with high mitosis.

5. Diagnosis

Synovial sarcoma.

6. Discussion and treatment

A 40-year-old female patient presented with painless growing mass in the prepatellar region. The differential diagnosis based on clinical and radiographic data included tenosynovial giant-cell tumor (solitary pigmented villonodular synovitis), chronic prepatellar bursitis, fibromatosis, chronic granulomatous infection (tuberculosis), benign neoplasms (lipoma/hemangioma/leiomyoma), and malignant neoplasms (synovial sarcoma/malignant fibrous histiocytoma/liposarcoma). Tenosynovial giant-cell tumor commonly presents in adults and is characterized by hemosiderin-laden macrophage microscopically.1 Chronic prepatellar bursitis was considered as there was history of prolonged history of doing household work in kneeling position and there was radiographic evidence of calcification in the mass. However, absence of pain and microscopic findings went against this diagnosis. We considered fibromatosis as the differential diagnosis owing to the consistency of the mass and the negative yield on fine needle aspiration twice. Fibromatosis is a locally aggressive tumor that display low heterogeneous signal pattern on both T1W and T2W MR image sequences. Histologically, it reveals fibroblasts in dense collagenous background.2 The absence of typical histopathological features excluded this diagnosis. Hemangioma was considered as possible diagnoses as the phleboliths present within may be confused with calcifications. The mass was, otherwise, clinically benign and slow growing with long duration of symptoms. But, this condition was excluded owing to absence of typical MR findings, operative and histopathological findings. We considered tuberculous etiology as differential diagnosis as the patient was resident of Indian subcontinent and this infection is known for its ability to present in various forms and guises.3 The pathology was excluded as there was absence of laboratory tests and typical histopathological features of tuberculous etiology (tuberculous granulation tissue, caseation, necrosis, epitheloid cell granuloma, and Langhans giant cells). Soft tissue sarcomas especially synovial sarcoma may present as mass around the knee. Typical histopathological findings of malignant fibrous histiocytoma or liposarcoma were not there, hence excluded.

Synovial sarcoma has been reported to be the fourth most common soft tissue sarcoma that may account for 2.5%–10% of all primary malignant soft tissue tumors.4,5 Despite the existence of vast literature, much controversy exists in the representative cell types of the tumor, biological behavior, prognostic factors, and role of adjuvant chemotherapy. The nomenclature appears a misnomer as neither it originates from synovium nor it is intra-articular in nature,6 though presents near the joints and knee joint (popliteal fossa) being the site of predilection.5,7–10 Very rarely, it may originate inside the joint.11 Young adults (15–40 years) are the most common affected age group by this neoplasm and the median age at the time of presentation has reported to be 30–38 years.5,8,9,12–15

The patients tend to present late owing to its clinically benign course and nonspecific symptomatology and for the same reason, even diagnosis may be delayed.5 It is a peculiar soft tissue tumor that displays a dual epithelial and mesenchymal differentiation.6,16 The presence of keratin positivity in the epithelial-type cells of biphasic synovial sarcoma corresponds with the true epithelial nature of these cells. Histologically, synovial sarcoma may be biphasic, monophasic, or poorly differentiated. The typical MR features most suggestive of a synovial sarcoma is an inhomogenous mass with multiple internal septations and infiltrative margins located near joints, particularly in presence of the evidence of calcification on radiographs/CT scan.17–20

Advanced stage at the time of presentation, male gender, older age group, truncal location of tumor, large size (more than 5 cm), monophasic subtype of tumor, osseous and neurovascular invasion of the tumor, and aggressive histopathological features (presence of tumor necrosis, mitotic activity, and high grade tumor) have been implicated to be the poor prognostic factors.6,7,10,12–14,21–24 In general, surgery is considered as the standard treatment for localized synovial sarcoma.7–9,13,14 Radiotherapy may be indicated in high grade tumors and for achieving local control of tumor after incomplete removal.25 Much controversy exists on the role of postoperative chemotherapy for synovial sarcoma.7,9,10,14,24,26 It has been suggested that chemotherapy may be useful in patients of ≥17 years age and with tumor size >5 cm.9 The presented case underwent en-bloc excision along with the overlying pseudocapsule, cuff of normal surrounding tissues and the redundant skin. Posteriorly, the periosteum of underlying patella and sheath of patellar tendon were also excised along with the mass. Radiotherapy referral was sought after histopathological findings of synovial sarcoma. The margins of the resected mass were clear both macroscopically and microscopically. Metastatic work-up of the tumor was done including contrast enhanced computed tomography of the chest and abdomen that revealed normal study. The patient underwent local radiotherapy to control the possible contamination of surgical site. Gradual knee mobilization was started after 4 weeks and she was kept under regular follow-up on out-patient basis. She was asymptomatic during latest follow-up at 18 months and had excellent knee function. The patient was informed that data concerning the case would be submitted for publication, and written, informed consent authorizing radiologic examination and photographic documentation was taken.

The article has following learning points: (1) Synovial sarcoma presents most commonly in young adults (2) The tumor may manifest as clinically benign growth, so the initial presentation may be delayed. The long duration of symptoms should not dissuade one considering this diagnosis (3) The presence of calcification in the mass should arise suspicion in the clinician's mind of this pathology (4) A good team work between the surgeon, radiologist, and pathologist will help reaching a correct and timely diagnosis.

Conflicts of interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Footnotes

This work was performed at The Maulana Azad Medical College & Associated Lok Nayak Hospital, New Delhi 110002, India.

References

- 1.Mendenhall W.M., Mendenhall C.M., Reith J.D., Scarborough M.T., Gibbs C.P., Mendenhall N.P. Pigmented villonodular synovitis. Am J Clin Oncol. 2006;29:548–550. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000239142.48188.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Myhre-Jensen O. A consecutive 7-year series of 1331 soft tissue tumours: clinicopathologic data. Comparison with sarcomas. Acta Orthop Scand. 1981;52:287–293. doi: 10.3109/17453678109050105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arora S., Sabat D., Maini L. The results of nonoperative treatment of craniovertebral junction tuberculosis: a review of twenty-six cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:540–547. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gustafson P. Soft tissue sarcoma: epidemiology and prognosis in 508 patients. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1994;259:1–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphey M.D., Gibson M.S., Jennings B.T., Crespo-Rodríguez A.M., Fanburg-Smith J., Gajewski D.A. From the archives of the AFIP. Imaging of synovial sarcoma with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2006;26:1543–1565. doi: 10.1148/rg.265065084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miettinen M., Virtanen I. Synovial sarcoma – a misnomer. Am J Pathol. 1984;117:18–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrassy R.J., Okcu M.F., Despa S., Raney R.B. Synovial sarcoma in children: surgical lessons from a single institution and review of the literature. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;192:305–313. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(00)00806-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buck P., Mickelson M.R., Bonfiglio M. Synovial sarcoma: a review of 33 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1981;156:211–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrari A., Gronchi A., Casanova M. Synovial sarcoma: a retrospective analysis of 271 patients of all ages treated at a single institution. Cancer. 2004;101:627–634. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis J.J., Antonescu C.R., Leung D.H. Synovial sarcoma: a multivariate analysis of prognostic factors in 112 patients with primary localized tumors of the extremity. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2087–2094. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.10.2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKinney C.D., Mills S.E., Fechner R.E. Intraarticular synovial sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:1017–1020. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199210000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bergh P., Meis-Kindblom J.M., Gherlinzoni F. Synovial sarcoma: identification of low and high risk groups. Cancer. 1999;85:2596–2607. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990615)85:12<2596::aid-cncr16>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singer S., Baldini E.H., Demetri G.D., Fletcher J.A., Corson J.M. Synovial sarcoma: prognostic significance of tumor size, margin of resection, and mitotic activity for survival. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1201–1208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.4.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skytting B.T., Bauer H.C., Perfekt R. Clinical course in synovial sarcoma: a Scandinavian sarcoma group study of 104 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1999;70:536–542. doi: 10.3109/17453679908997839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiss S.W., Goldblum J.R. Malignant soft tissue tumors of uncertain type. In: Weiss S.W., Goldblum J.R., editors. Enzinger and Weiss's Soft Tissue Tumors. 4th ed. Mosby; St Louis: 2001. pp. 1483–1565. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher C. Synovial sarcoma. Ann Diagn Pathol. 1998;2:401–421. doi: 10.1016/s1092-9134(98)80042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones B.C., Sundaram M., Kransdorf M.J. Synovial sarcoma: MR imaging findings in 34 patients. Am J Roentgenol. 1993;161:827–830. doi: 10.2214/ajr.161.4.8396848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marzano L., Failoni S., Gallazzi M., Garbagna P. The role of diagnostic imaging in synovial sarcoma. Our experience. Radiol Med. 2004;107:533–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morton M.J., Berquist T.H., McLeod R.A., Unni K.K., Sim F.H. MR imaging of synovial sarcoma. Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156:337–340. doi: 10.2214/ajr.156.2.1846054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valenzuela R.F., Kim E.E., Seo J.G., Patel S., Yasko A.W. A revisit of MRI analysis for synovial sarcoma. Clin Imaging. 2000;24:231–235. doi: 10.1016/s0899-7071(00)00219-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deshmukh R., Mankin H.J., Singer S. Synovial sarcoma: the importance of size and location for survival. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;419:155–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spillane A.J., A'Hern R., Judson I.R., Fisher C., Thomas J.M. Synovial sarcoma: a clinicopathologic, staging, and prognostic assessment. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3794–3803. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.22.3794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tateishi U., Hasegawa T., Beppu Y., Satake M., Moriyama N. Synovial sarcoma of the soft tissues: prognostic significance of imaging features. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2004;28:140–148. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200401000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trassard M., Le Doussal V., Hacène K. Prognostic factors in localized primary synovial sarcoma: a multicenter study of 128 adult patients. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:525–534. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.2.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuklo T.R., Temple H.T., Owens B.D. Preoperative versus postoperative radiation therapy for soft-tissue sarcomas. Am J Orthop. 2005;34:75–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarcoma Meta-analysis Collaboration Adjuvant chemotherapy for localised resectable soft-tissue sarcoma of adults: meta-analysis of individual data. Lancet. 1997;350:1647–1654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]