Abstract

Peptide deformylase (PDF) is a prokaryotic enzyme that catalyzes the deformylation of nascent peptides generated during protein synthesis and water molecules play a key role in these hydrolases. Using X-ray absorption near edge spectroscopy (XANES) and ab initio calculations we accurately probe the local atomic environment of the metal ion binding in the active site of PDF at different pH values and with different metal ions. This new approach is an effective way to monitor existing correlations among functions and structural changes. We show for the first time that the enzymatic activity depends on pH values and metal ions via the bond length of the nearest coordinating water (Wat1) to the metal ion. Combining experimental and theoretical data we may claim that PDF exhibits an enhanced enzymatic activity only when the distance of the Wat1 molecule with the metal ion falls in the limited range from 2.15 to 2.55 Å.

Peptide deformylase (PDF, EC 3.5.1.27) is an important member of the metallo-hydrolase superfamily. In eubacterium as well as mitochondria and chloroplasts, the protein synthesis starts from formylmethionine-tRNA, resulting in the polypeptides with N-terminals formylated1. During the elongation of the polypeptide chain, the formyl group is removed hydrolytically by PDF2,3,4, which may be a universally conserved feature of the prokaryotic protein synthesis and an essential component for bacterial survival5. Actually, due to the continuous increase of the tolerance to conventional antibiotics, the synthesis of new and effective drugs is imperative. PDF is an attractive target for the design of new antibiotics because at present, the deformylation does not occur in the cytoplasm of eucaryotic cells6.

Previous researches showed that the activity of Leptospira interrogans PDF (LiPDF), the bacterial zinc PDF with a high activity, is strongly dependent on both pH values and metal ions. The catalytic activity of the LiPDF decreases for pH < 7.0 and is nearly constant in the pH range from 7.5 to 10.57. Moreover, in many macromolecules both structures and functions are also affected by pH, a parameter associated with the concentration of hydrogen ions. The majority of proteins exhibit an optimal pH, but why and how the biological activity of proteins depends by pH remains an open problem, in particular at the atomic scale. Different LiPDF structures at different pH values are available in the protein crystallography databank (PDB code: 1Y6H pH3.0, 1VEV pH6.5, 1VEY pH7.0, 1SV2 pH7.5, 1VEZ pH8.0)8. Nevertheless, the biochemical mechanism of the pH-dependent enzymatic behavior has never been clearly demonstrated mainly because, within the error bars of the crystallography structures, folds of the active sites in LiPDFs are substantially identical.

On the basis of the presence of a classical HEXXH zinc-binding motif, PDF was originally thought to be a zinc enzyme. On the contrary, PDFs utilize different metal ions in different organisms9. Different from Escherichia coli PDF (EcPDF) in which the Co2+-bound form (Co-EcPDF) is active, while the Zn2+-bound form (Zn-EcPDF) is inactive8, the Co2+-bound LiPDF (Co-LiPDF) and the Ni2+-bound LiPDF (Ni-LiPDF) are less active than Zn-LiPDF10. Although the catalytic mechanism is unknown, Jain et al. pointed out that at the end of the catalytic reaction, the metal ion in the active site might be penta- or tetra-coordinated11. However, the LiPDF with the native Zn ion shares the same coordination sphere in the crystal structure of the inactive Zn-PDFs, not in agreement with the enzymatic activity scenario proposed by Jain et al..

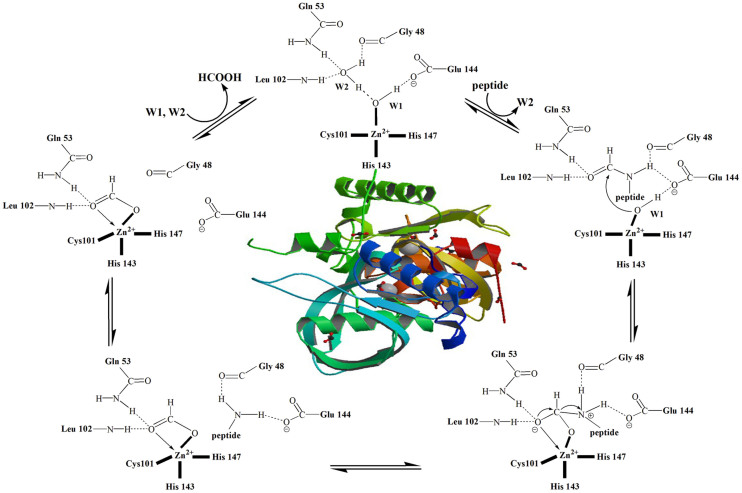

In the active centre of most PDFs, metal ions are coordinated with the side chains of one cysteine and two histidines plus a water molecule. The latter plays a significant role in the deformylate reaction, performing the nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl carbon of the formyl group which leads to the transition state of the reaction12. This was turned out to be the rate-limiting step13. The reaction scheme is schematically described in Fig. 1. A similar situation occurs in other metallohydrolases14,15,16 pointing out that to explore and understand the catalytic activity and the reaction mechanism is mandatory to study water molecules in the reaction center.

Figure 1. The action scheme for PDF12 and inside the crystal structure of PDF (PDB code: 1Y6H).

X-ray absorption spectroscopy on biological systems (BioXAS) is a short-range probe sensitive to local structure variations, extremely useful to reconstruct in details and understand the environment of selected atoms in biological systems17,18,19. BioXAS allows investigating samples in a wide variety of forms, such as proteins as oriented single crystals, disoriented micro-crystals, frozen or room-temperature solutions or proteins inside membranes. XAS includes the extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) and the X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES). The EXAFS analysis is reliable and provides the average distance between metal and its ligands while XANES is able to obtain three-dimensional structural information, although a quantitative analysis is still challenging in complex systems. Here, we present and discuss XANES spectra at the Zn and Co K-edge of LiPDF and EcPDF vs. pH. Combining ab initio multiple scattering calculations, we applied the MXAN package to analyze XANES data and extract subtle local structural changes around metal sites in LiPDF at different pH values and in the EcPDF at optimum pH, describing with particular emphasis the location and geometry of bonded water molecules.

Results and Discussion

Correlation between structure, function and pH

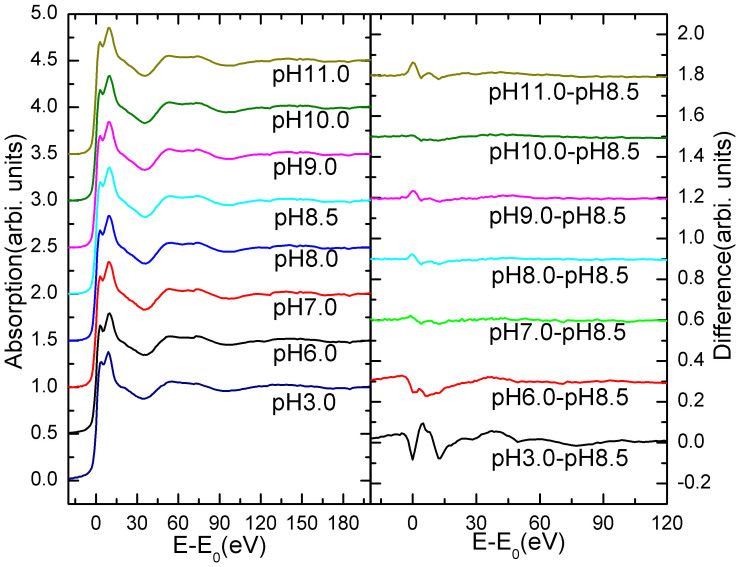

Zn K-edge experimental XANES spectra of LiPDF at different pH values are compared in Fig. 2. In the right panel we compare the differences of XANES spectra of each solution with the spectrum at pH 8.5, the mid value of the range in which the protein has the highest activity, taken as the reference.

Figure 2. Left: Zn K-edge XANES spectra of the LiPDF vs. pH; Right: comparison among differences between Zn K-edge XANES spectra and the reference spectrum collected at pH 8.5.

Differences are negligible except at the edge and in particular for pH values: 3 and 6.

We may recognize that differences in the pH range from 7.0 to 11.0 are extremely small, while larger differences occur for pH values < 7.0, particularly in the edge region (−10 ~ 20 eV). As it is well known, XAS features in this region are due to multiple scattering contributions from the nearest neighbours and reflect both the geometric and the electronic structure of the probed system. Because for a Zn2+ ion the 3d orbital are completely filled, the main peak at the Zn K-edge reflects the local geometrical configuration in an accurate way. In particular, the splitting of the main peak at the Zn K-edge points out the presence of two different chemical environments involving the metal ion.

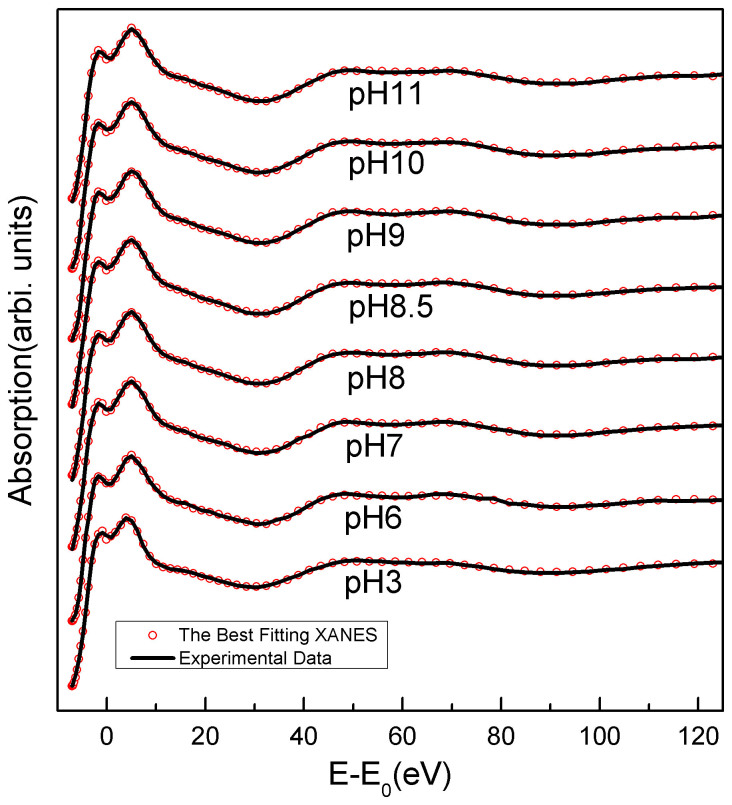

In order to obtain accurate structural information around the metal site, based on the crystallographic structure of the LiPDF (PDB code 1Y6H (B)), we performed a quantitative analysis of the XANES spectrum using the MXAN code20. Experimental XANES spectra (black) of the LiPDF vs. pH and best-fit calculations (red dots) are compared in Fig. 3. A good agreement occurs among experimental data and best-fit theoretical curves for the whole energy range. All features in the near-edge region are successfully reproduced. Using alternative starting structures the calculations returned the same results. The refined main distances of the best fits of the structures vs. pH are summarized in Table 1. The statistical errors of independent parameters with the certain Rsq values were evaluated by the MIGRAD subroutine of MXAN code21. The error values of Wat1-Wat2 and Wat1-Glu44 were estimated from the independent parameters of Zinc-Wat1, Zinc-Wat2 and Zinc-Glu44.

Figure 3. Comparison among experimental Zn K-edge XANES spectra vs. pH (black) and simulations (red dot).

Table 1. Refined critical distances of the best fit at different pH.

| Atom pairs | Model structure(Å) | pH3.0 distance(Å) | pH6.0 distance(Å) | pH7.0 distance(Å) | pH8.0 distance(Å) | pH8.5 distance(Å) | pH9.0 distance(Å) | pH10.0 distance(Å) | pH11.0 distance(Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rsq (square residue) | - | 0.453 | 0.245 | 0.599 | 0.466 | 0.362 | 0.450 | 0.377 | 0.507 |

| Zinc His147 | 2.15 | 2.06 ± 0.02 | 2.01 ± 0.02 | 2.02 ± 0.02 | 2.02 ± 002 | 2.02 ± 0.02 | 2.03 ± 0.02 | 2.03 ± 0.03 | 1.99 ± 0.02 |

| Zinc His143 | 2.07 | 2.06 ± 0.02 | 2.10 ± 0.02 | 2.04 ± 0.02 | 2.05 ± 0.02 | 2.05 ± 0.02 | 2.04 ± 0.02 | 2.04 ± 0.02 | 2.07 ± 0.02 |

| Zinc Cys101 | 2.40 | 2.25 ± 0.03 | 2.25 ± 0.03 | 2.25 ± 0.03 | 2.23 ± 0.03 | 2.24 ± 0.03 | 2.23 ± 0.03 | 2.23 ± 0.03 | 2.26 ± 0.04 |

| Zinc Wat1 | 2.31 | 2.58 ± 0.02 | 2.57 ± 0.02 | 2.52 ± 0.02 | 2.50 ± 0.02 | 2.50 ± 0.02 | 2.50 ± 0.02 | 2.52 ± 0.02 | 2.53 ± 0.02 |

| Zinc Wat2 | 3.90 | 4.05 ± 0.05 | 3.91 ± 0.04 | 3.97 ± 0.04 | 4.00 ± 0.04 | 4.00 ± 0.04 | 4.00 ± 0.04 | 4.05 ± 0.04 | 3.92 ± 0.04 |

| Wat1 Wat2 | 3.20 | 2.59 ± 0.06 | 3.00 ± 0.05 | 2.99 ± 0.05 | 3.05 ± 0.05 | 2.97 ± 0.05 | 2.95 ± 0.05 | 2.99 ± 0.06 | 2.87 ± 0.05 |

| Wat1 Glu144 | 2.67 | 2.57 ± 0.07 | 2.51 ± 0.06 | 2.54 ± 0.07 | 2.52 ± 0.06 | 2.50 ± 0.06 | 2.48 ± 0.06 | 2.52 ± 0.06 | 2.56 ± 0.07 |

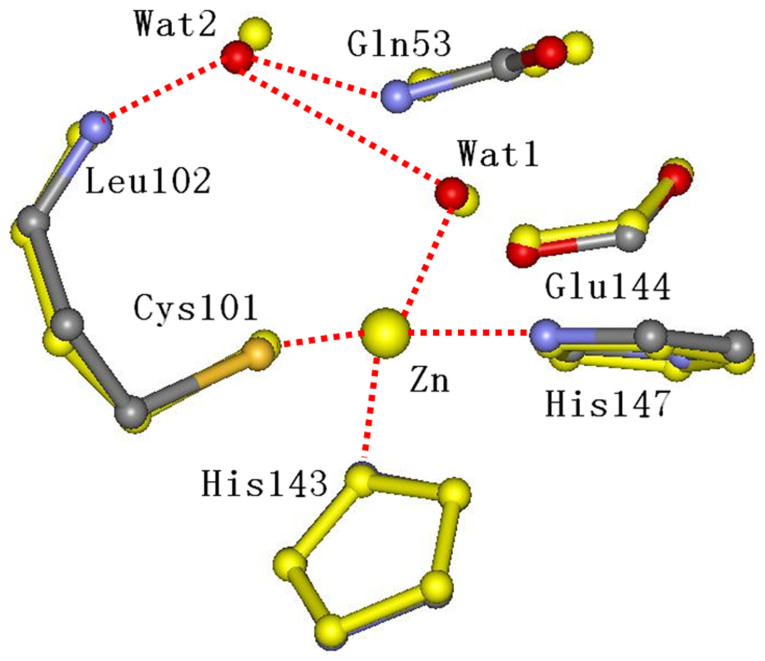

From Table 1 it is evident that the most significant differences among local structures at different pH is the bond length between the zinc ion and two water molecules, a condition that points out the key role for water. In the native state of LiPDF at pH 8.5, the Wat1 coordinating with the Zn ion (2.50 Å) is connected to the Wat2 (2.97 Å) and the side chain oxygen of the Glu144 (2.50 Å) by hydrogen bonds. The side chain of the conserved Leu102 donates protons to the Wat2 (2.59 Å) molecule, which forms other hydrogen bonds with the amide in the main chain of Gln53 (3.43 Å) and the oxygen in the main chain of Gly48 (3.41Å). In the transition state, the Wat2 is replaced by the carbonyl oxygen of the formyl group12. The comparison of the local structure of the LiPDF at pH 8.5 (best fit - coloured sticks) and the crystallographic model structure (thick yellow sticks) is shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4. Comparison between the local structure of the best fit at pH 8.5 (colored sticks) and the crystallographic model structure (thick yellow sticks).

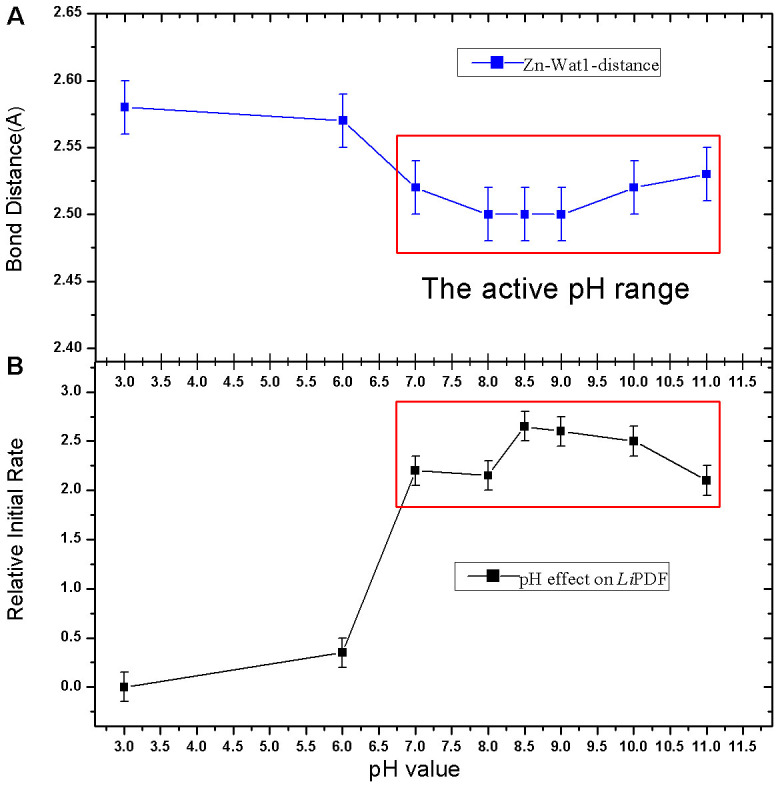

Outlined in Fig. 5, we also show the correlation between the zinc-Wat1-distance (bond distance between the Zn ion and the Wat1 molecule) and pH. We hypothesize that the enzymatic activity mechanism induced by pH is associated to the changes in the Zn-Wat1 bond distance that affects the ionization degree of the Wat1 molecule. In the catalytic process the nucleophilic addition of metal-bound water to the carbonyl of the N-terminal formyl of the peptide substrate is indeed a crucial step. The metal acts as an electron-withdrawing group helping the deprotonation of the Wat1, as well as a Lewis acid activating the carbonyl bond with the substrate12. In an acid environment (pH 3–pH 6), with the increase of the Zn-Wat1-distance, the proton of the Wat1 is more localized and the charge transfer towards the amide at the N-terminus of the peptide, even with the help of Glu144, is more difficult. This mechanism may explain why the enzymatic activity of LiPDF is much lower in an acid environment.

Figure 5. Correlation between the Zn-Wat1 distance vs. pH (A) and the activity of the LiPDF vs. pH (B).

Correlation between structure, function and metal-dependence

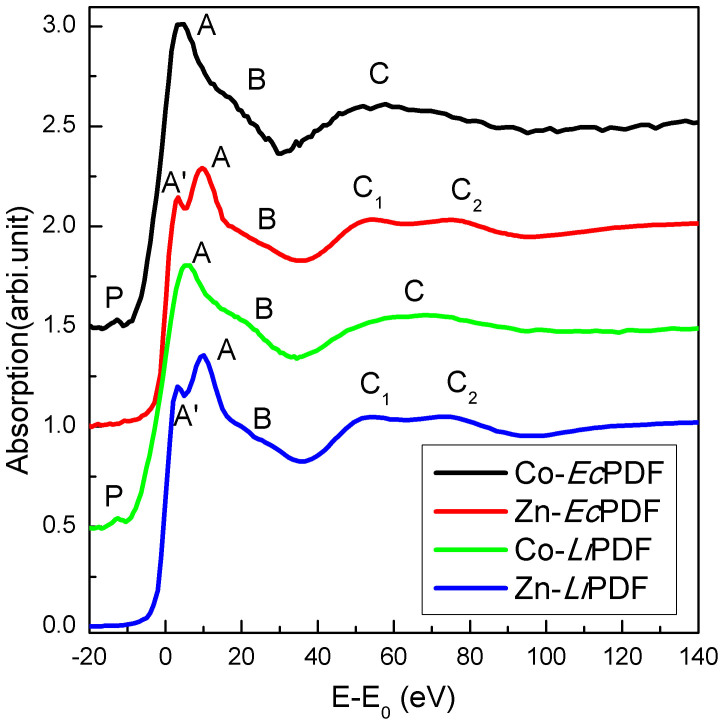

We also investigated the metal-dependent enzymatic activity of PDFs. The Zn K-edge XANES spectra of Zn-EcPDF (red) and Zn-LiPDF (blue), the Co K-edge XANES spectra of Co-EcPDF (black) and Co-LiPDF (green) in a buffer solution at pH 8.0 are compared in Fig. 6. The peak A is due to multiple-scattering events among the nearest neighbours and reflects the geometry as well as the electronic structure of the systems. In view of the different electronic configurations of Zn2+ and Co2+, a simple comparison of the main peak A has no meaning. Moreover, because of the unoccupied 3d orbital of the Co2+, a pre-edge peak (peak P) is observed in the XANES spectra of both Co-LiPDF and Co-EcPDF. This feature is dipole-forbidden in a centro-symmetric configuration that is an allowed quadrupole electronic transitions (1s to 3d transition). For the absorbed 3d metal with local spherical symmetry (such as with hexagon coordinators), this transition is forbidden. When the spherical symmetry breaks, such as ligands distorting and coordinator number decreasing, the XANES will present a weak pre-edge peak. As reported in previous work22,23, the weak pre-edge peak suggests a distorting penta-coordination structure with the low electronegative coordinating atoms.

Figure 6. Zn K-edge XANES spectra of Zn-EcPDF (red) and Zn-LiPDF (blue) and Co K-edge XANES spectra of Co-EcPDF (black) and Co-LiPDF (green) in a buffer solution at pH 8.0.

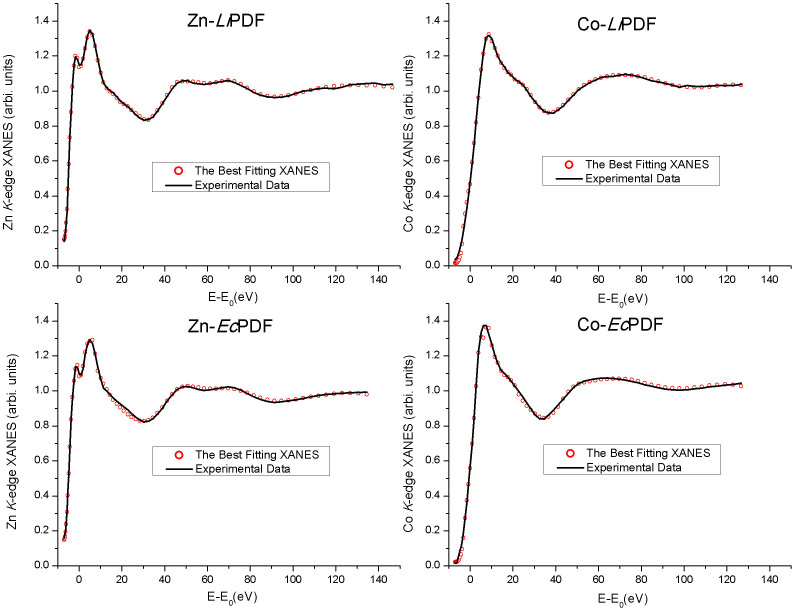

We performed a quantitative analysis of XANES spectra with the MXAN package. According to the above, Fig. 7 and Table 2 show that the most significant difference in the local structure around metal ions in Co/Zn-LiPDF and Co/Zn-EcPDF is the length of the metal-Wat1 bond. The Co-Wat1 distance in Co-LiPDF is 1.91 Å, much shorter than in Zn-LiPDF (2.50 Å). However, the Co-Wat1 distance of Co-EcPDF is 2.15 Å, significantly longer than in Zn-EcPDF (2.05 Å). Actually, the strong binding with water inhibits the transition of the metal ion from a penta- to tetra-coordination in the catalytic process and increases the distance between water and Glu144/133 (Wat1-Glu). This mechanism weakens the polarization of Glu144/133 to Wat1 and prevents the transfer of a proton from Wat1 to the substrate, the key step in the catalytic process of PDFs12. Thus, the strong binding of the metal-Wat1 reduces the polarizability of Glu144/133 towards Wat1 and significantly decreases the probability of the transfer of a proton from the Wat1 to the amide at the N-terminus, which actually takes into account the reduction of the enzymatic activity of Co-LiPDF and Zn-EcPDF with respect to Zn-LiPDF and Co-EcPDF.

Figure 7. Comparison among best fits of XANES spectra (red dots) and experimental spectra (black lines) in buffer solutions at pH 8.0 of (A) Zn-LiPDF; (B) Co-LiPDF; (C) Zn-EcPDF and (D) Co-EcPDF.

Table 2. Refined critical distances and error bars of the best fits of Zn-LiPDF, Co-LiPDF, Zn-EcPDF and Co-EcPDF.

| Atom pairs | 1Y6H(B) Model structure (Å) | Zn-LiPDF pH8.0 distance (Å) | Co-LiPDF pH8.0 distance (Å) | 1XEO Model structure (Å) | Zn-EcPDF pH8.0 distance (Å) | 1XEM Model structure (Å) | Co-EcPDF pH8.0 distance (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rsq (square residue) | - | 0.466 | 0.453 | - | 0.812 | - | 1.362 |

| Metal His147 (His 136) | 2.15 | 2.02 ± 002 | 1.95 ± 0.02 | 1.99 | 2.02 ± 0.02 | 2.00 | 1.90 ± 0.02 |

| Metal His143 (His 132) | 2.07 | 2.05 ± 0.02 | 1.81 ± 0.02 | 2.08 | 2.04 ± 0.02 | 2.00 | 2.04 ± 0.02 |

| Metal Cys101 (Cys 90) | 2.40 | 2.23 ± 0.03 | 2.31 ± 0.03 | 2.25 | 2.25 ± 0.03 | 2.31 | 2.29 ± 0.03 |

| Metal Wat1 | 2.31 | 2.50 ± 0.02 | 1.91 ± 0.02 | 2.09 | 2.05 ± 0.02 | 2.32 | 2.15 ± 0.02 |

| Metal Wat2 | 3.90 | 4.00 ± 0.04 | 3.47 ± 0.05 | 3.88 | 3.97 ± 0.04 | 3.80 | 3.90 ± 0.04 |

| Wat1 Wat2 | 3.20 | 3.05 ± 0.05 | 3.57 ± 0.06 | 3.06 | 2.99 ± 0.05 | 3.16 | 3.65 ± 0.05 |

| Wat1 Glu144 (Glu 133) | 2.67 | 2.52 ± 0.06 | 3.25 ± 0.07 | 2.69 | 3.05 ± 0.07 | 2.85 | 2.76 ± 0.06 |

Summarizing, XAS is a powerful tool to resolve the local structure around the metal atom in biological samples at low concentration, although the EXAFS method may hardly detect subtle structural changes. XANES data show that PDF may exhibit a high enzymatic activity when the nearest metal coordinating water molecule is localised at a distance from the metal ion in the range 2.15–2.55 Å, while a low enzymatic activity can be associated to metal-Wat1 distances outside this range, i.e., longer than 2.55 Å or shorter than 2.15 Å.

Conclusion

This work is an accurate investigation of pH- and metal-dependent enzymatic activity of the peptide deformylase. Local structures around the central metal ions were characterized using XANES spectroscopy combined with ab initio calculations. All features in the near-edge region of the spectra were successfully reproduced and detailed structural information around the metal ion was obtained. Data clearly point out that the enzymatic activity depends on pH values and metal ions via the metal-Wat1 distance. Actually, the proton of the Wat1 is localized and the charge transfer towards the amide is blocked with the extremely long metal-Wat1 distance in an acid environment (pH < 6). However, a too short metal-Wat1 distance induces a strong binding with water, which inhibits the transition of the metal ion from a penta- to tetra-coordination in the catalytic process.

From a careful comparison among structures of other PDFs, we may also claim that PDF exhibits a high enzymatic activity when the Wat1 is located within a limited range of distance, i.e., between 2.15 and 2.55 Å from the metal ion. Data provide accurate structural information and point out a real novel scenario regarding the mechanism responsible of the observed pH dependent enzymatic activity. The new unique structural information appears useful to trigger further applications of these proteins, focused in particular on the development of new drugs and more effective antibiotics.

Methods

E.coli BL21(DE3) cells carrying plasmid pET22b-LiPDF were expressed as reported in Ref. 7. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 25 ml of buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl pH7.5, 10 mM NaCl). After sonication cell debris were removed by centrifugation. The supernatant (25 ml) was applied onto a HiTrapTM 5 ml Q HP (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) column equilibrated with buffer B (50 mM Tris-HCl pH8.5, 10 mM NaCl). The column was eluted with 250 ml of buffer B plus a linear gradient of 10 mM–1 M NaCl (AKTA purifier 900, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The fractions with LiPDF activity were concentrated and applied to a SuperdexTM 75 column (16/60,Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) pre-equilibrated with buffer C (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.5, 50 mM NaCl). The fractions containing LiPDF activity were collected. The sample homogeneity was monitored by SDS-PAGE and the protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay with BSA as the standard. EcPDF was purified using the same procedures.

To acquire samples of LiPDF at different pH values, we used the purification protocol as described above, by direct dialysis exchanges respectively with 50 mM NaHCO3/Na2CO3 (pH 9.0, pH 10, pH 11), 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5, pH 8.0), 50 mM NaH2PO4/Na2HPO4 (pH 6.0, pH 7.0) and 50 mM Gly-HCl (pH 3.0). All PDF concentrations were about 60 mg/ml and the Zn2+ and Co2+ concentrations were around 200 ppm.

X-ray absorption spectroscopy measurements at the Zn and Co K-edges were carried out at the beam line 4W1B of the Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility (BSRF) and the beam line 14W1 of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) in the fluorescence yield mode at room temperature. The typical energy of the storage ring was 2.5 GeV in BSRF and 3.5 GeV in SSRF and experiments were performed with a decreasing electron current from 250 mA to 160 mA. The incident beam intensity was monitored using an ionization chamber flowed by a 25% argon-doped nitrogen mixture while the fluorescence signal was collected by means of a Lytle detector flowed by argon gas. As previously described, after the experiments, we recycled the samples and measured their enzymatic activity7. Data showed that the activity of proteins is preserved.

In order to extract structural/geometrical information around the metal site, we performed a quantitative analysis of XANES spectra using the MXAN package. This software is capable of performing a quantitative analysis of a XANES spectrum from the absorption edge up to ~200 eV via comparison between experimental data and theoretical calculations obtained by changing relevant geometrical parameters around the photon absorber site24,25. The X-ray absorption cross sections were calculated using the full multiple scattering approach in the framework of the muffin-tin (MT) approximation for the shape of the potential26,27. In this case, exchange and correlation parts of the potential were determined on the basis of the local density approximation of the self energy. Inelastic processes were taken into account by a convolution with a broadening Lorentzian function having an energy-dependent width of the form Γ(E) = Γc + Γmfp(E) in which the constant part Γc takes care of both the core-hole lifetime (1.8 eV)28 and the experimental resolution (1.5 eV), while the energy-dependent term represents intrinsic and extrinsic inelastic processes25,29,30. The method takes into account Multiple-Scattering events in a rigorous way through the evaluation of the scattering path operator26,31. Its reliability has been successfully tested over the years in a wide number of different applications24,29. In this case spectra typically converge when the cluster includes 39 atoms within a radius of 5.5 Å. Therefore the local structure of the PDF active center may be properly represented by an atomic cluster containing fifty atoms within 6 Å from the metal ion.

Author Contributions

Z.W. and W.G. designed the experiments. P.C., Y.W., X.G. and M.Y. performed experiments and data analysis. P.C., Y.W., W.C., F.Y., H.Z. and Z.W. performed the calculations. Y.D. and Y.X. supplied some biological experiment apparatus. W.G. and Z.W. led the whole work and the analysis. P.C., Y.W., W.C. and Z.W. wrote the text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to A. Marcelli for useful advices on the early draft of this manuscript. We sincerely acknowledge the staff of the XAS beamline of BSRF and SSRF for the technology supports in the XAS experiments. This work was partly supported by the Knowledge Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (KJCX2-YW-N42), the States Key Project for Fundamental Research (2012CB825801), the Key Important Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (10734070), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC 11275227 & 10905067) and the Science Fund for Creative Research Groups (11321503).

References

- Meinnel T., Mechulam Y. & Blanquet S. Methionine as translation start signal - a review of the enzymes of the pathway in Escherichia-coli. Biochimie. 75, 1061–1075 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams J. M. On release of formyl group from nascent protein. J. Mol. Biol. 33, 571–589 (1968). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball L. A. & Kaesberg P. Cleavage of N-terminal formylmethionine residue from a bacteriophage coat protein in-vitro. J. Mol. Biol. 79, 531–537 (1973). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston D. M. & Leder P. Deformylation and protein biosynthesis. Biochemistry 8, 435–443 (1969). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazel D., Pocher S. & Marliere P. Genetic-characterization of polypeptide deformylase, a distinctive enzyme of eubacterial translation. EMBO J. 13, 914–923 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopalan P. T. R., Yu X. C. & Pei D. H. Peptide deformylase: a new type of mononuclear iron protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 12418–12419 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. K., Chen Z. F. & Gong W. M. Enzymatic properties of a new peptide deformylase from pathogenic bacterium Leptospira interrogans. Biochem. Bioph. Res. Co. 295, 884–889 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z. C., Song X. M. & Gong W. M. Novel conformational states of peptide deformylase from pathogenic bacterium Leptospira interrogans - Implications for population shift. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 42391–42396 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen K. T., Wu J. C., Boylan J. A., Gherardini F. C. & Pei D. Zinc is the metal cofactor of Borrelia burgdorferi peptide deformylase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 468, 217–225 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. K., Ren S. X. & Gong W. M. Cloning, high-level expression, purification and crystallization of peptide deformylase from Leptospira interrogans. Acta. Cryst. D 58, 846–848 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain R. K., Hao B., Liu R. P. & Chan M. K. Structures of E.coli peptide deformylase bound to formate: Insight into the preference for Fe2+ over Zn2+ as the active site metal. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 4558–4559 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker A. et al. Iron center, substrate recognition and mechanism of peptide deformylase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Bio. 5, 1053–1058 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. L., Li Z. S. & Fang W. H. Theoretical investigation of astacin proteolysis. J. Inorg. Biochem. 111, 70–79 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimoto T. et al. Crystal structures of creatininase reveal the substrate binding site and provide an insight into the catalytic mechanism. J. Mol. Biol. 337, 399–416 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gennadios H. A., Whittington D. A., Li X. C., Fierke C. A. & Christianson D. W. Mechanistic inferences from the binding of ligands to LpxC, a metal-dependent deacetylase. Biochemistry. 45, 7940–7948 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita K. et al. Substitution of Glu122 by glutamine revealed the function of the second water molecule as a proton donor in the binuclear metal enzyme creatininase. J. Mol. Biol. 396, 1081–1096 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordlander E. et al. Heterometal cuboidal clusters MFe4S6(PEt3)4Cl (M = V, Mo) - synthesis, structural-analysis by crystallography and EXAFS, and relevance to the core structure of the iron molybdenum cofactor of nitrogenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115, 5549–5558 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Conradson S. D. et al. Selenol binds to iron in nitrogenase iron-molybdenum cofactor: an extended x-ray absorption fine structure study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 91, 1290–1293 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone K. L., Behan R. K. & Green M. T. X-ray absorption spectroscopy of chloroperoxidase compound I: Insight into the reactive intermediate of P450 chemistry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 102, 16563–16565 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z. C., Song X. M., Li Y. K. & Gong W. M. Unique Structural Characteristics of Peptide Deformylase from Pathogenic Bacterium Leptospira interrogans. J. Mol. Biol. 339, 207–215 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chillemi G. et al. Evidence for Sevenfold Coordination in the First Solvation Shell of Hg(II) Aqua Ion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 5430–5436 (2007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunes L. A. Study of the K edges of 3d transition metals in pure and oxide form by x-ray-absorption spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 27, 2111–2131 (1983) [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z. Y., Ouvrard G., Gressier P. & Natoli C. R. Ti and O K edges for titanium oxides by multiple scattering calculations: Comparison to XAS and EELS spectra. Phys. Rev. B 55, 10382–10391 (1997) [Google Scholar]

- Della Longa S., Arcovito A., Girasole M., Hazemann J. L. & Benfatto M. Quantitative analysis of x-ray absorption near edge structure data by a full multiple scattering procedure: the Fe-CO geometry in photolyzed carbonmonoxy-myoglobin single crystal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 155501 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardelli A. et al. A crystal-chemical investigation of Cr substitution in muscovite by XANES spectroscopy. Phys. Chem. Miner. 30, 54–58 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Natoli C. R. & Benfatto M. A unifying scheme of interpretation of x-ray absorption-spectra based on the multiple-scattering theory. J. Phys. (Paris) Colloq. 47, 11–23 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z. Y. et al. Sulfur K-edge x-ray-absorption study of the charge transfer upon lithium intercalation into titanium disulfide. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 2101–2104 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuggle J. C. & Inglesfield J. E. Unoccupied electronic states - fundamentals for XANES, EELS, IPS and BIS – introduction. Top Appl. Phys. 69, 1–23 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Benfatto M., Della Longa S. & Natoli C. R. The MXAN procedure: a new method for analysing the XANES spectra of metalloproteins to obtain structural quantitative information. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 10, 51–57 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscioni O. M., D'Angelo P., Chillemi G., Della Longa S. & Benfatto M. Quantitative analysis of XANES spectra of disordered systems based on molecular dynamics. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 12, 75–79 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z. Y. et al. Symmetry dependence of X-ray absorption near-edge structure at the metal K edge of 3d transition metal compounds. Appl. Phys. Lett. 79, 1918–1920 (2001). [Google Scholar]