Abstract

Objective

The literature is inconsistent regarding the level of pain and disability in frozen shoulder patients with or without diabetes mellitus. The aim of this study is to evaluate some demographic features of frozen shoulder patients and to look into the disparity of information by comparing the level of pain and disability due to frozen shoulder between diabetic and non-diabetic people.

Design

This is a prospective comparative study. People with frozen shoulder attending an outpatient department were selected by consecutive sampling. Disability levels were assessed by the Shoulder Pain & Disability Index (SPADI). Means of pain and disability scores were compared using unpaired t-test.

Results

Among 140 persons with shoulder pain 99 (71.4%) had frozen shoulder. From the participating 40 frozen shoulder patients, 26 (65%) were males and 14 (35%) were females. Seventeen participants (42.5%) were diabetic, two (5%) had impaired glucose tolerance and 21 (52.5%) patients were non-diabetic. Mean disability scores (SPADI) were 51 ± 15.5 in diabetic and 57 ± 16 in non-diabetic persons. The differences in pain and disability level were not statistically significance (respectively, p = 0.24 and p = 0.13 at 95% confidence interval).

Conclusions

No difference was found in level of pain and disability level between frozen shoulder patients with and without diabetes.

Keywords: Adhesive capsulitis, Diabetics, SPADI, Shoulder pain

1. Introduction

Frozen shoulder, or adhesive capsulitis, is a condition characterized by painful and limited active and passive range of motion of the shoulder.1 The incidence of adhesive capsulitis has been found to be two to four times higher in diabetics than in the general population.2 The estimated prevalence is 11–30% in diabetic patients and 2–10% in non-diabetics. Adhesive capsulitis appears at an earlier age in patients with diabetes.3

The literature represents greater the level of pain and disability in frozen shoulder patients with diabetes mellitus than without. For instance, an Australian study showed shoulder pain and quality of life were poorer among diabetics with current shoulder symptoms than non-diabetics.4 Again, diabetic persons with frozen shoulder were found to have reduced mobility compared to people who do not have diabetes.5 Moreover, diabetics were reported to have worse functional outcomes as measured by disability and quality of life questionnaires (SPADI) compared to non-diabetics with frozen shoulder.6

The literature, which shows greater level of pain and disability in frozen shoulder patients with diabetes mellitus, suggests that treatment strategy might also vary between these groups. For instance, patients with diabetes and adhesive capsulitis showed less improvement of pain and function following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair than their non-diabetic counterparts.7 Another work showed that shoulder pain in diabetes was often more resistant to conventional treatment.3 Hence, quantification of disability level independently in frozen shoulder patients with diabetes is crucial. Increasing intensity of pain scores was associated with poor glycaemic control in diabetic frozen shoulder patients shown by higher HbA1c level.8 This information raises the possibility and importance of prevention of ‘greater’ disability due to frozen shoulder in diabetic population by strict control of glycaemic state.

Conversely, a review article revealed that people with diabetes and frozen shoulder have significantly less pain compared with patients who do not have diabetes.3 Again, the Australian study also did not show significant difference in disability (p = 0.16) between diabetic and non-diabetic group.4 This represents the dissimilarities among articles regarding the level of pain and disability.

A literature search found that only few studies discussed the disability level in frozen shoulder patients and very few looked into the pain and disability level among diabetic group. All the studies were carried out in industrialized countries. The ethnicity, living environment, lifestyle and body configuration of the people of the Asian region is quite different from western countries. So, study results from Asian low resource areas might also be different and help fill up the gap of knowledge. Unfortunately, studies of these areas have been neglected previously by western journals. Moreover, in Bangladesh, a recent population-based study showed a sharp and significant increase in the prevalence of diabetes from 2.3% to 6.8% over 5 years9 pointing towards the burden of frozen shoulder and its disability in this area in future.

2. Methodology

This is a prospective comparative study. It was done on the outpatients of the department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, ‘XX’ Medical College Hospital. Patients who came with shoulder pain were the target population of the study. During the data collection period, 140 patients were registered as having shoulder pain. Participants were selected from the registered patients by consecutive sampling.

2.1. Participants

Patients aged 30–65, clinically diagnosed as cases of frozen shoulder according to diagnostic hallmarks were allocated from 140 patients with shoulder pain. Shoulder stiffness patients due to specific or secondary causes (e.g. osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, post traumatic or post surgical stiffness) were excluded from participants list. Severely co-morbid (e.g. recent history of myocardial infarction) and pregnant women were also excluded. Suspected inflammatory cases, osteoarthritis and calcific tendinitis were excluded by ESR level and radiological features. Patients who had previous treatment for frozen shoulder were not included, either.

2.2. Data collection and study procedure

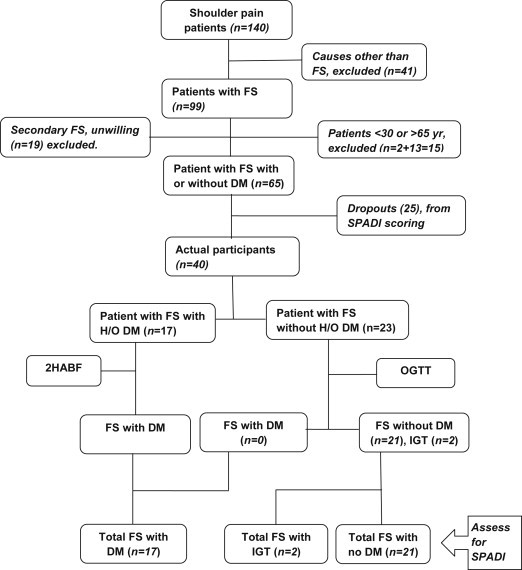

The study procedure is summarized by a flow chart (Fig. 1). Patients with shoulder pain attending the outpatient clinics of a hospital, department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation were examined by two junior post graduate trainee doctors. Relevant history was taken and a physical examination was done. The patients with frozen shoulder were diagnosed clinically and referred to the investigators. Frozen shoulder patients who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were given a plain radiograph of the affected shoulder to exclude other pathology. Patients with known diabetes were subjected to 2 h postprandial blood glucose. Patients with no known history of diabetes were subjected to a 2-sample oral glucose tolerance test. Diabetes was diagnosed according to WHO criteria. Patients were assessed for pain and disability level. Data was collected in a semi-structured questionnaire (Fig. 2). The questionnaire consisted of 16 questions of which 10 were open-ended and 6 were close-ended.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart shows summary of the study procedure.

FS = frozen shoulder; DM = diabetes mellitus; H/O = history of; 2HABF = blood sugar 2 h after breakfast; IGT = impaired glucose tolerance; OGTT = oral glucose tolerance test.

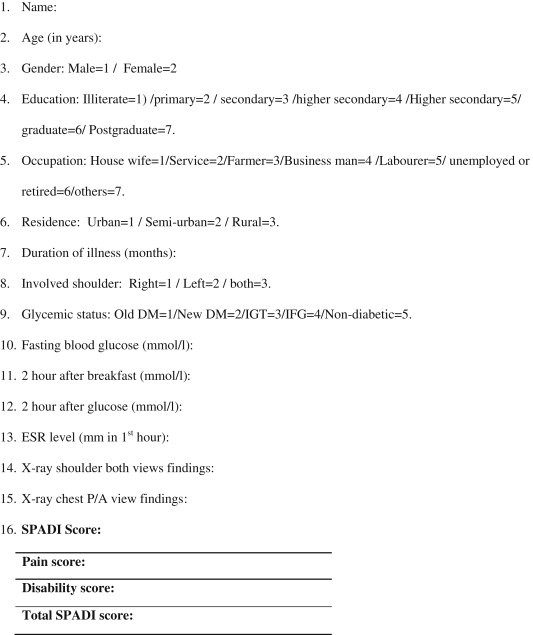

Fig. 2.

Chart showing the case record form. DM = Diabetes mellitus IGT = Impaired glucose tolerance. IFT = Impaired fasting glycaemia. SPADI = Shoulder pain and disability index.

2.3. Frozen shoulder (Adhesive capsulitis)

The three hallmarks for diagnosis of frozen shoulder are progressive shoulder stiffness, severe pain (especially at night) and a near complete loss of passive and active external rotation of the shoulder.10 Presence of all the three features was the diagnostic and inclusion criteria of this study.

2.4. Diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance states

Patients who had history of diabetes and who were on oral hypoglycemic agents (OHA) or insulin or both at the time of data collection were considered to be ‘old diabetes’ cases. For the diagnosis of new diabetes cases, World Health Organization (WHO)11 was followed. Summary of WHO diagnostic criteria for diabetes and intermediate hyperglycemia is shown in Table 1.11 Both the new and old diabetes cases were allocated in ‘diabetic’ group.

Table 1.

Summary of WHO diagnostic criteria (1999) for diabetes and intermediate hyperglycaemia.

| Classifications | Venous plasma glucose levels | |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | Fasting 2-h glucose |

<6.1 mmol/l Not specified but <7.8 mmol/l implied |

| Diabetes | Fasting glucose 2-h glucose |

≥7.0 mmol/l or ≥11.1 mmol/l |

| IGT | Fasting glucose <8.0 mmol/l 2-h glucose |

<7.0 mmol/l and ≥7.8 and <11.1 mmol/l |

| IFG | Fasting glucose 2-h glucose |

≥6.1 and <7.0 mmol/l and <7.8 mmol/l (if measured) |

Foot notes: IGT = Impaired Glucose Tolerance; IFT = Impaired Fasting Glycaemia; 2-h = 2 h after ingestion 75 gm glucose solution.

2.5. Assessment scale

A shoulder pain and disability index (SPADI) was used to assess pain & disability in frozen shoulder as in other studies. SPADI is a self-reported measure developed to evaluate shoulder pathology. It consists of 13 items (Table 2) divided into two subtypes: pain (5 items) & disability (8 items). SPADI is a valid measure to assess pain & disability. Minimum Detectable Change in score (90% confidence) = 13 points (Change less than this may be attributable to measurement error).12–14

Table 2.

Shows SPADI (Shoulder Pain and Disability Index).

| Pain scale | |||||||||||||

| How severe is your pain: | |||||||||||||

| 1. At its worst. | No pain | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Worst pain imaginable |

| 2. When lying on involved side. | No pain | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Worst pain imaginable |

| 3. Reaching for something on a high shelf. | No pain | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Worst pain imaginable |

| 4. Touching the back of your neck. | No pain | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Worst pain imaginable |

| 5. Pushing with the involved arm. | No pain | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Worst pain imaginable |

| Disability scale | |||||||||||||

| How much difficulty did you have: | |||||||||||||

| 1. Washing your hair. | No difficulty | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | So difficult required help |

| 2. Washing your back. | No difficulty | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | So difficult required help |

| 3. Putting on an undershirt or pullover sweater. | No difficulty | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | So difficult required help |

| 4. Putting on a shirt that buttons down the front. | No difficulty | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | So difficult required help |

| 5. Putting on your pants. | No difficulty | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | So difficult required help |

| 6. Placing an object on a high shelf. | No difficulty | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | So difficult required help |

| 7. Carrying a heavy object of 10 pounds. | No difficulty | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | So difficult required help |

| 8. Removing something from your back pocket. | No difficulty | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | So difficult required help |

2.6. Ethical measures

Ethical clearance (Memo no: CMC/2012/PG/66) was taken from the Ethical Committee of ‘XX’ Medical College, ‘XX’. Informed written consents were also taken from all participants prior to study.

3. Results

Table 3 summarizes some of the demographic and clinical factors of the frozen shoulder patients. The total study population was 140 with shoulder symptoms, among which 99 had frozen shoulder (71.4%). From the actual participants (40 frozen shoulder patients), 26 were (65%) males and 14 were (35%) females. Mean age of the patients was 53 years and median age was 50 years. Twenty respondents of our study (50%) resided in urban areas and 12 of them (30%) came from villages. The final 8 (20%) lived in semi-urban areas.

Table 3.

Demographic and clinical factors of frozen shoulder patients in diabetics and non-diabetics.

| Characteristics | In diabetic (n = 17) | In non-diabetic (n = 23) | Statistical difference, values | p value (significant p < 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean), years | 52.8 | 54.4 | t = 0.48 | 0.31 |

| Female gender, n (%) | 6 (35%) | 8 (35%) | χ2 = 0.001 | 0.97 |

| Literacy, n (%) | 14 (82%) | 15 (65%) | χ2 = 1.43 | 0.23 |

| Patients from rural area, n (%) | 11 (65%) | 9 (39%) | χ2 = 2.55 | 0.19 |

| Manual worker, n (%) | 6 (35%) | 10 (43%) | χ2 = 0.27 | 0.60 |

| Both shoulder, n (%) | 2 (12%) | 4 (17%) | χ2 = 0.10 | 0.74 |

| Duration of FS (mean), months | 5.35 | 6.87 | t = 0.82 | 0.21 |

| Waist circumference (mean), cm | 86 | 79 | t = 2.35 | 0.01 |

| Pain score (mean) | 56.7 | 60.9 | t = 0.72 | 0.24 |

| Disability (SPADI) score (mean) | 51 ± 15.5 | 57 ± 16 | t = 1.09 | 0.13 |

Foot notes: n = number, SPADI = Shoulder Pain and Disability Index.

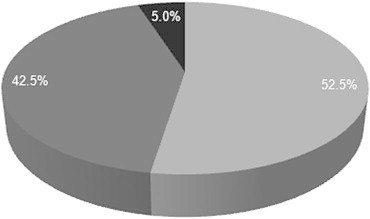

In the 40 adhesive capsulitis patients, 17 persons (42.5%) were diabetic, 2 (5%) had impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) and remaining 21 participants (52.5%) were non-diabetic (Fig. 3). Mean duration of diabetes was 5.5 years. From the 17 diabetic patients, 10 (59%) had blood glucose within normal limit and 7 had beyond (41%) at the time of data collection. Mean duration of frozen shoulder in all patients was 5 months. Eight diabetic patients under went HBA1c analysis and mean value was 7.34%.

Fig. 3.

Pie chart expresses the glycaemic status of the participants.

= Old DM;

= Old DM;  = Non-DM;

= Non-DM;  = IGT.

= IGT.

DM = Diabetes mellitus; IGT = Impaired glucose tolerance.

Fifty two percent (21) of the participants had adhesive capsulitis in the right shoulder, 32.5% (13) had solely in left shoulder and 17.5% (7) experienced in both shoulder. Only one shoulder was involved in 82.5% of the participants.

Both pain and disability level of the patients with frozen shoulder was assessed and compared between diabetic and non-diabetic patients. There was no significant statistical difference in pain score (p = 0.24, CI = 95%) and disability/SPADI score (p = 0.13, CI = 95%) between the frozen shoulder patients with or without diabetes mellitus.

4. Discussion

This study represents the first prospective gathering of data on frozen shoulder in a low resource country, and is unique among most other studies in that it actually confirmed diabetes after the diagnosis of frozen shoulder. The findings help us to understand the pathophysiology that may be seen in clinical situations.

The mean age of patients with frozen shoulder in the study was 53 years. A clinical review by Dias R et al, found almost similar ‘peak age’ of patients with frozen shoulder (56 years).15 Another study in Turkey found the common age of frozen shoulder to be between 40 and 60 years.16 Both the study supports our findings. Some authors have postulated that the higher prevalence in older persons may be because frozen shoulder is an inflammatory response to ageing changes in the shoulder joint and or tendons of the shoulder. However there is no definite proof of this.17

In this study, the prevalence of diabetes in frozen shoulder patients (42.5%) was quite similar to an American study, where prevalence was 39%.2 Although the reason of high prevalence of diabetes in frozen shoulder patients is unknown, it is believed that in patients with diabetes are associated with microvascular disease. Microvascular diseases cause abnormal collagen repair, which predisposes patients to adhesive capsulitis.18 In addition, increased glycosylation of collagen protein and increased formation of abnormal glycation end products and their subsequent accumulation was found to have detrimental effect on a number of cellular and extracellular processes that might fascilitate adhesion and fibrosis.19 Patients with diabetes often present with fibrosis elsewhere (i.e., Dupuytren's contracture).18

Twenty-six out of 40 adhesive capsulitis patients in this study were male (65%). Many articles do not support these findings.6 However, in a recent study by Watson & Dalziel, prevalences for men and women were near equal; 57% of the patient population was female and 43% was male.20 None of the articles revealed any cause of female predominance.21

Frozen shoulder was found on right shoulder in 50% patients. Some studies showed it to be more common on left side. However, in a British study, the right shoulder was found more frequently involved than the left, particularly in men. This finding is consistent with ours. Only one shoulder was involved in 72% of the participants, a finding similar to the same British study, which shows 72% involvement of solely one shoulder.22

Higher scores of pain and disability (SPADI) in patients with diabetes were found than those patients without diabetes. But no statistically significant difference in pain and disability in frozen shoulder patients with or without diabetes were detected. An Australian population-based study,23 also showed no significant difference in disability (SPADI) score.

Frozen shoulder is a common complaint; however there remains much to be learned about the disorder. While this study demonstrates that presentation in lower resource countries is not dissimilar to that in reports from industrialized countries, there are important differences in activity, participation, and environment in low resource countries that need to be further explored.

5. Conclusion

No difference was found in level of pain and disability level between frozen shoulder patients with and without diabetes. Adhesive capsulitis was the most common diagnosis in patients with intrinsic shoulder pain. Around half of the frozen shoulder patients had either diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance. Peak age of frozen shoulder was 53 years it was most common in males.

Conflicts of interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Acknowledgements

I would like show my gratitude to the honourable Professor Abdus Salek Mollah, MD, PhD, Head of Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Chittagong Medical College Hospital, Bangladesh. I am also grateful to Dr. Asiful Hoque and to the doctors and the alliance health workers of our Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Chittagong Medical College Hospital, Bangladesh for their assistance. Thanks to the patients who gave their consents to participate in this study.

Footnotes

We declare that a changed version of the abstract of this study was presented in the 2nd International Rehab Forum Conference at Dhaka, Bangladesh in 2012 and was published in their souvenir.

References

- 1.Kelley M.J., McClure P.W., Leggin B.G. Frozen shoulder: evidence and a proposed model guiding rehabilitation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009 Feb;39(2):135–148. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2009.2916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tighe C.B., Oakley W.S., Jr. The prevalence of a diabetic condition and adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder. South Med J. 2008 Jun;101(6):591–595. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181705d39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith L.L., Burnet S.P., McNeil J.D. Musculoskeletal manifestations of diabetes mellitus. Br J Sports Med. 2003;37:30–35. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.37.1.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laslett L.L., Burnet S.P., Jones J.A. Musculoskeletal morbidity: the growing burden of shoulder pain and disability and poor quality of life in diabetic outpatients. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007 May–Jun;25(3):422–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cole A., Gill T.K., Shanahan E.M. Is diabetes associated with shoulder pain or stiffness? Results from a population-based study. J Rheumatol. Feb 2009;36(2):371–377. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080349. [abstract] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Page P., Labbe A. Adhesive capsulitis: use of evidence to integrate your intervention. N Am J Sports Phys Ther. 2010 December;5(4):266–273. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clement N.D., Hallett A., MacDonald D. Does diabetes affect outcome after arthroscopic repair of the rotator cuff? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010 Aug;92(8):1112–1117. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B8.23571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laslett L.L., Burnet S.P., Jones J.A. Predictors of shoulder pain and shoulder disability after one year in diabetic outpatients. Rheumatology. 2008;47(10):1583–1586. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1183–1197. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.7.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong P.L.K., Tan H.C.A. A review on frozen shoulder. Singapore Med J. 2010;51(9):694–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization . Department of Non-Communicable Disease Surveillance, WHO; Geneva: 1999. Definition, Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus and its Complications; Part 1. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roach K.E., Budiman-Mak E., Sonhsiridej N. Development of shoulder pain & disability index. Arthritis Care Res. 1991;4(4):143–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tveitå K.E., Sandvik L., Ekeberg O.M. Factor structure of the shoulder pain and disability index in patients with adhesive capsulitis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:103. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Macdermid J.C., Solomon P., Parkachin K. The shoulder pain and disability index demonstrates factor, construct and longitudinal validity. BMC Musculoskeletal Disord. 2006 Feb;10:7–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-7-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dias R., Cutts S., Massoud S. Frozen shoulder: clinical review. BMJ. 2005;331:1453. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7530.1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ulusoy H., Sarica N., Arslan S. The efficacy of supervised physiotherapy for treatment of adhesive capsulitis. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2011;112(4):204–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watson L. Life Care; November 2000. Frozen Shoulder.http://www.lifecare.com.au/frozen-shoulder.html Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siegel L.B., Cohen N.J., Gall E.P. Adhesive capsulitis: a sticky issue. Am Fam Physician. 1999 Apr 1;59(7):1843–1850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas S.J., Claire McDougall C., Brown I.D.M. Prevalence of symptoms and signs of shoulder problems in people with diabetes mellitus. J Should Elb Surg. 2007;16(6):748–751. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.02.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watson L., Bialocerkowski A., Dalziel R. Hydrodilatation (distension arthrography): a long-term clinical outcome series. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41:167–173. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.028431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sheridan M.A., Hannafin J.A. Upper extremity: emphasis on frozen shoulder. Orthop Clin North Am. 2006;37:531–539. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wright V., Haq A.M. Periarthritis of the shoulder. Aetiological considerations with particular reference to personality factors. Ann Rheum Dis. 1976 June;35(3):213–219. doi: 10.1136/ard.35.3.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roy A. 2012 Jan 18. Adhesive Capsulitis in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation.http://emedicine.medscape.com (updated on 2012 Feb 14). Available at: Increasing Prevalence of Type 2 Diabetes in a Rural Bangladeshi Population: A Population Based Study for 10 Years. [Google Scholar]