Abstract

Objectives:

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is the most common cause of lower urinary tract symptoms in elderly men. Selective alfa1-adrenergic antagonists are now first-line drugs in the medical management of BPH. We conducted a single-blind, parallel group, randomized, controlled trial to compare the effectiveness and safety of the new alfa1-blocker silodosin versus the established drug tamsulosin in symptomatic BPH.

Materials and Methods:

Ambulatory male BPH patients, aged above 50 years, were recruited on the basis of International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS). Subjects were randomized in 1:1 ratio to receive either tamsulosin 0.4 mg controlled release or silodosin 8 mg once daily after dinner for 12 weeks. Primary outcome measure was reduction in IPSS. Proportion of subjects who achieved IPSS <8, change in prostate size as assessed by ultrasonography and changes in peak urine flow rate and allied uroflowmetry parameters, were secondary effectiveness variables. Treatment emergent adverse events were recorded.

Results:

Data of 53 subjects – 26 on silodosin and 27 on tamsulosin were analyzed. Final IPSS at 12-week was significantly less than baseline for both groups. However, groups remained comparable in terms of IPSS at all visits. There was a significant impact on sexual function (assessed by IPSS sexual function score) in silodosin arm compared with tamsulosin. Prostate size and uroflowmetry parameters did not change. Both treatments were well-tolerated. Retrograde ejaculation was encountered only with silodosin and postural hypotension only with tamsulosin.

Conclusions:

Silodosin is comparable to tamsulosin in the treatment of BPH in Indian men. However, retrograde ejaculation may be troublesome for sexually active patients.

KEY WORDS: Benign prostatic hyperplasia, international prostate symptom score, randomized controlled trial, silodosin, tamsulosin

Introduction

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) are a common problem of aging males. Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is the most common cause of LUTS in elderly men over 70 years of age. BPH, usually, starts in men in their 50s; by the age of 60 years, 50% of men have histological evidence of BPH and 80% of men in their 70s suffer from BPH-related LUTS.[1]

Symptomatic BPH is characterized by a mix of obstructive and irritative symptoms, collectively known as prostatism. The former include difficulty in initiation of micturition (hesitancy), poor or interrupted flow, post-void dribbling, and sensation of incomplete voiding that can manifest as the piss-en-deux (urge to revisit the toilet immediately after voiding) phenomenon. The latter includes frequency of micturition, nocturia, dysuria and urgency or even urge incontinence. Acute retention of urine is an unfortunate obstructive complication. Histologically, BPH affects both glandular epithelium and connective tissue stroma of the prostate to a variable degree. Pathophysiologically, BPH related LUTS results not only from fixed mechanical obstruction of the prostatic urethra but also from a dynamic component to the obstruction from prostatic muscle activity.[2]

The definitive management of symptomatic BPH is surgery to relieve the obstruction imposed by the enlarged portion of the prostate. However, apart from invasiveness, there are potential complications of surgery, including the unfortunate development of permanent urinary incontinence.[3] Thus, there is a need for continued research on drug treatment for symptomatic BPH. Currently, two main categories of drugs are used for the treatment of symptomatic BPH; one blocks the α1-adrenoreceptors (e.g., doxazosin, terazosin, tamsulosin, alfuzosin, silodosin), the other inhibits the enzyme 5α-reductase (e.g., finasteride, dutasteride) thereby preventing the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone and depriving the prostatic tissue of trophic androgenic influence. The former category is expected to provide relatively rapid symptom relief starting within 2-6 weeks, while the latter acts more slowly restricting the hyperplasia, and taking 6 months or longer to produce symptom relief.

Alfa-blockers are now considered as first-line drugs in the medical management of BPH.[4] Silodosin,[5] an α1A-adrenoceptor blocker introduced into the Indian market recently, is said to be highly selective for this receptor subtype. Our objective was to compare the effectiveness and safety of silodosin in elderly Indian men with BPH, in comparison to the older established α1-blocker tamsulosin,[6] through a randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Materials and Methods

The study was conducted as a single blind, parallel group, randomized, controlled trial at the urology outpatient department of a tertiary care hospital in Kolkata. Approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee, and the study was duly registered with Clinical Trials Registry, India [CTRI/2014/01/004366].

Sixty-one ambulatory, treatment naïve, male patients over 50 years of age with bothersome LUTS from BPH and International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS)[7] >7 were recruited during the period July 2012 to June 2013. Those patients with history of LUTS but not BPH, acute retention of urine in past 6 months, raised prostate specific antigen (PSA) level at baseline, serious co-morbidity of vital organs, use of concomitant medication having anticholinergic, androgenic or estrogenic influence, on other α-adrenergic antagonists or diuretics or with a history of prostatic or per urethral surgery or substance abuse were excluded.

Subjects were randomized in 1:1 ratio to one of the two study groups in fixed blocks of 8, using computer generated random number list. They took either tamsulosin 0.4 mg controlled-release capsule or silodosin 8 mg capsule once daily after dinner for 12 weeks. Marketed brands of both drugs were used (Cap URIMAX and Cap SILOFAST, respectively; both marketed by M/s Cipla Ltd., Mumbai). The capsules were removed from their commercial blister strip packaging and repackaged in air-tight, screw cap containers and suitably labeled and coded as trial medication. Repackaging was done with the help of residents not otherwise involved in the study. Capsule identity was not revealed to the patients who received the total medication in three installments. Allocation concealment was achieved using the serially numbered, opaque, sealed envelope technique. The randomization list and the code breaking authority was retained by a senior pharmacologist not directly interacting with the subjects. Patients were followed up at 4 and 8-week from the start of the treatment, with the final study visit being at 12-week.

Compliance was assessed by measuring the number of capsules returned at the next study visit. It was deemed to be excellent if not >10% of scheduled doses were missed, good if not >20% were missed, fair if not >30% were missed, and poor for any situation worse than fair.

The primary effectiveness variable for this study was symptom relief as assessed by IPSS scoring. The total score was taken as the sum of seven individual symptom scores. In addition, the quality of life (QoL) assessment was done on a 7-point scale and quality of sexual life assessed by a 6-item questionnaire that form part of the broader symptom scoring. The secondary effectiveness variables were: (a) Proportion of subjects who became completely or relatively symptom free (IPSS <8) after 12-week of treatment (b) change in prostate size, in terms of volume, as assessed at ultrasonography (USG) by a radiologist unaware of treatment allocation and (c) changes in peak urine flow rate and allied parameters assessed at uroflowmetry by a blinded operator.

For safety assessment, subjects underwent standard laboratory investigations (complete blood count, fasting plasma glucose, routine liver function tests and creatinine level) at baseline and study end. Vital signs were recorded at each study visit and all treatment-emergent adverse events, either reported spontaneously by trial subjects or noted by the attending investigator, were recorded in the structured case report form. History suggestive of postural hypotension and retrograde ejaculation (in sexually active patients) was specifically sought at each visit.

The target sample size was 25 evaluable patients in each group. This was calculated to detect a difference of 4 in total IPSS between groups with 80% power and 0.05 probability of type 1 error, assuming a standard deviation of 5 in total symptom score. Allowing for a 20% dropout rate, this translated to a recruitment target of 32 subjects per group or 64 subjects overall.

Efficacy analysis was on modified intention-to-treat basis for subjects reporting for at least one post-baseline follow-up visit. All subjects randomized were considered for adverse event analysis. Missing values were dealt with by the last observation carried forward strategy. The null hypothesis was that test drug (silodosin) is equivalent to an active comparator (tamsulosin) in the treatment of symptomatic BPH. IPSS and allied scores had skewed distribution, and therefore were compared between groups by Mann–Whitney U-test and within group by Friedman's analysis of variance, followed by Dunn's test for post-hoc comparison between two individual time points. Prostate volume and uroflowmetry parameters were also non-parametric, and study-end versus baseline comparisons were done by Wilcoxon's matched pairs signed rank test. Numerical variables that were normally distributed were compared between groups by Student's independent samples t-test. Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was employed for intergroup comparison of categorical variables, as appropriate. All analyses were two-tailed, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistica version 6 (Tulsa, Oklahoma: StatSoft Inc., 2001) and Graphpad Prism version 5 (San Diego, California: GraphPad Software Inc., 2007) software were used for the statistical analysis.

Results

Sixty-one patients were enrolled in this study. Six subjects did not return even for the first follow-up visit. One patient withdrew consent to participate in the trial, and another subject withdrew due to itching all over the body just after starting tamsulosin. Fifty-three patients (86.89%) provided data evaluable for effectiveness –26 in silodosin group and 27 in the tamsulosin group. Figure 1 depicts the flow of study participants.

Figure 1.

Silodosin in comparison to tamsulosin in benign prostatic hyperplasia: Flow of study participants

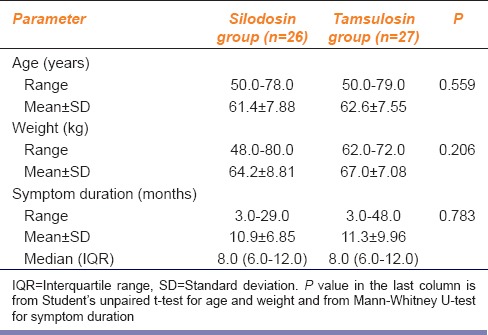

Baseline profiles of the subjects are summarized in Table 1. Evidently, the majority of patients were in their sixties or seventies and the median symptom duration at presentation was 8 months in both groups.

Table 1.

Silodosin in comparison to tamsulosin in benign prostatic hyperplasia: Baseline clinical profile of the study subjects

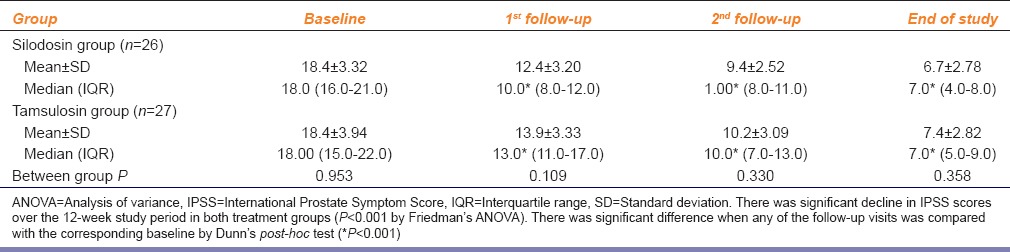

Table 2 depicts the serial change in IPSS in the two groups – the scores declined significantly from baseline in both groups (change from median 18 to 7 in both) but remained comparable between groups throughout the 12-week study period. The number of subjects who became completely or relatively symptom-free, that is achieved IPSS <8, were also comparable between groups –15 in both (P = 1.000).

Table 2.

Silodosin in comparison to tamsulosin in benign prostatic hyperplasia: IPSS changes in the study groups

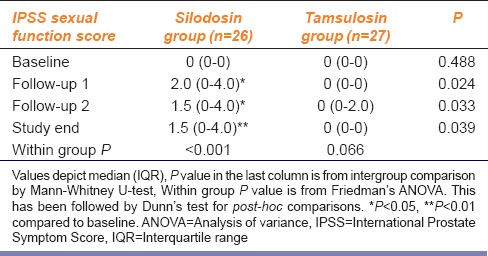

Table 3 depicts the IPSS Sexual Function Score changes in the study groups. This did not change with tamsulosin but increased significantly from baseline with silodosin, indicating a worsening of sexual performance.

Table 3.

Silodosin in comparison to tamsulosin in benign prostatic hyperplasia IPSS: Sexual function score changes in the study groups

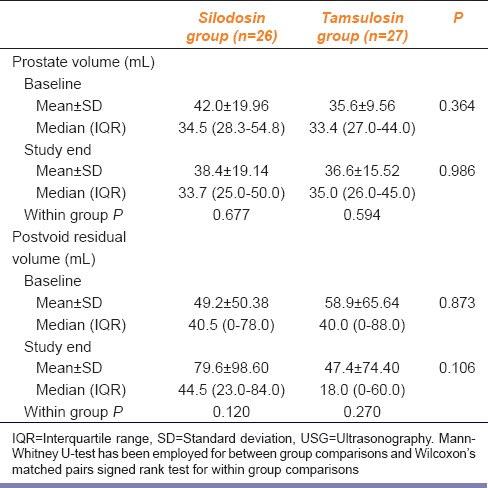

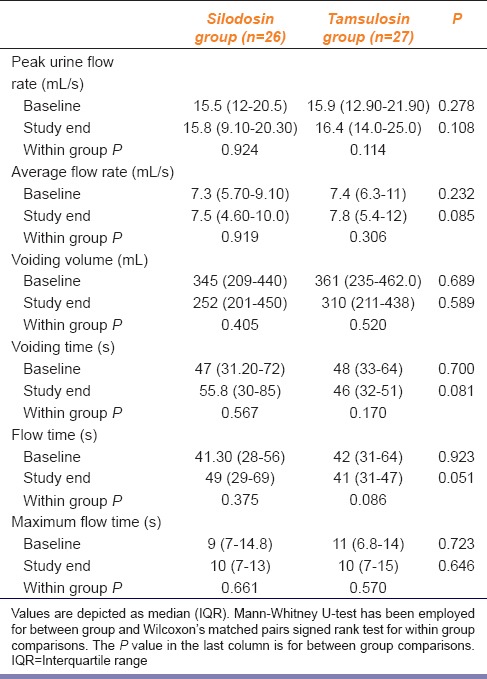

There was no change in prostate size or post-void residual urine after 12-week of treatment in both groups as shown in Table 4. Tamsulosin arm experienced 1 mL increase in prostate volume which, however, was not significant statistically. Comparison between the pre- and post-treatment peak urine flow rate also did not reveal anything remarkable in either group. The values are summarized in Table 5. Modest improvements in other uroflowmetry parameters were seen, but these were not significant statistically.

Table 4.

Silodosin in comparison to tamsulosin in benign prostatic hyperplasia: Change in prostate size as assessed by USG

Table 5.

Silodosin in comparison to tamsulosin in benign prostatic hyperplasia: Comparison of pre- and post-treatment uroflowmetry parameters

Adverse events were reported for 15 patients out of the 61 recruited (24.59%) – 6 subjects had multiple complaints. However, there were no significant changes in weight or vital signs (heart rate and blood pressure) and laboratory safety parameters. Treatment emergent events encountered numbered 12 in the silodosin arm (commonest dyspepsia in 5 instances) and 10 in the tamsulosin arm (commonest headache and postural hypotension in 3 instances each). There were 3 reports of retrograde ejaculation among 13 sexually active men (23.08%) in the silodosin arm and none in the tamsulosin arm. There were no instances of postural hypotension in the silodosin arm. All adverse events were mild in nature and did not require interruption of trial medication. There were no hospitalizations owing to adverse events. Compliance was excellent in over 92% subjects in both study arms and good in the rest.

Discussion

Benign prostatic hyperplasia is non-malignant enlargement of the prostate caused by cellular hyperplasia of both glandular and stromal elements.[2,8] According to the European Association of Urology 2011 guidelines,[9] α-blockers are currently the preferred first-line therapy for all men with moderate or severe LUTS/BPH. The other strategy for medical therapy for BPH is the use of 5α-reductase inhibitors, like finasteride and dutasteride, which are effective in decreasing the risk of urinary retention and hematuria in men with large prostate glands. However, their role in patients with frank LUTS but small prostate gland is yet to be established. Our study drug silodosin, a highly selective α1A-adrenoceptor antagonist, was developed by Kissei Pharmaceutical Company, Japan.[10] Silodosin is reported to be 583 times more selective for α1A than for α1B, and 56 times more selective for α1A than for α1D receptors.[11]

Although safety and efficacy of drugs are expected to be established prior to marketing, there is scope for evaluating drugs further in the post-marketing phase. Since silodosin has been introduced into the Indian market recently and is reported to be highly selective for the α1A-adrenoceptor blocker, we sought to ascertain whether this offers any clinical advantage compared to the older drug tamsulosin. It is important that such head-to-head comparisons be undertaken by independent groups (that is not the companies manufacturing or marketing the product) to assess whether a newly introduced drug is offering real value addition to the therapeutic armamentarium or is just a “me too” drug. Therefore even the finding that silodosin, efficacy-wise, does not add further to tamsulosin in the drug therapy of BPH in Indian patients is useful information.

Published studies from other countries report that silodosin is comparable to tamsulosin in the management of BPH. In a multicentric RCT conducted by Chapple et al.[12] it was found that the change from baseline in the IPSS total score with both silodosin and tamsulosin was significantly superior to that with placebo: Difference between placebo and active drug was −2.3 (95% confidence interval [CI], −3.2 to −1.4) with silodosin and −2.0 (95% CI, −2.9 to −1.1) with tamsulosin. Responder rates according to total IPSS were significantly higher with silodosin (66.8%) and tamsulosin (65.4%) than with placebo (50.8%). The authors concluded that the overall efficacy of silodosin is not inferior to tamsulosin.

Another non-inferiority trial conducted by Yu et al.[13] found that, of the 170 (81.3%) patients who completed the study, 86.2% in the silodosin group versus 81.9% in the tamsulosin group achieved a ≥25% decrease in IPSS (P = 0.53). The mean difference (silodosin minus tamsulosin) in IPSS change from baseline was −0.60 (95% CI −2.15 to −0.95), showed the non-inferiority of silodosin 4 mg twice daily to tamsulosin 0.2 mg once daily in patients with symptomatic BPH.

The first double-blind, placebo-controlled, RCT comparing tamsulosin and silodosin was reported in 2006.[14] Patients received silodosin 4 mg twice daily, tamsulosin 0.2 mg once daily, or a placebo for 12-week. The changes in the total IPSS from the baseline in the silodosin, tamsulosin, and placebo groups were −8.3, −6.8 and −5.3 respectively. The authors concluded that the silodosin was better than a placebo and not inferior to tamsulosin. Marks et al.[15] from a pooled analysis of two RCTs in United States reported that symptom relief was rapid and differences (silodosin versus placebo) in IPSS score and subscores increased by week 12.

A recent systematic review conducted by Ding et al.[16] has also suggested that silodosin is effective therapy for LUTS in men with BPH and is not inferior to 0.2 mg tamsulosin. We have conducted our study with 0.4 mg tamsulosin, the standard starting dose used by urologists in India, and have found similar result. The final IPSS scores at 12-week were significantly less than baseline for both tamsulosin and silodosin. However, scores remained comparable between the two study groups throughout the 12-week duration of the study. These results suggest that silodosin effectiveness is similar to tamsulosin in the short-term treatment of BPH in Indian men. The QoL component was also comparable between groups at 12-week. The proportion of subjects who became completely or relatively symptom-free at the end of 12-week of treatment also did not differ significantly between groups; reinforcing the conclusion from the primary efficacy variable.

Selective α1-blockers, unlike 5α-reductase inhibitors, are not expected to affect prostate size.[4,17] The present study had change in prostate volume and changes in peak urine flow rate (Qmax) and allied uroflowmetry parameters, as secondary efficacy variables. As expected, these did not change significantly in either group. Our findings are in conformity with those in earlier studies.[18,19] Chapple et al.[12] reported that an increase in Qmax was observed in all groups–the adjusted mean change from baseline to end was 3.77 mL/s for silodosin, 3.53 mL/s for tamsulosin, and 2.93 mL/s for placebo, but the changes for silodosin and tamsulosin were not statistically significant versus placebo because of a particularly high placebo response. At end-point, the percentage of responders by Qmax were 46.6%, 46.5%, and 40.5% in the silodosin, tamsulosin, and placebo treatment groups, respectively. These differences in proportions were also not statistically significant. Yu et al.[13] have also reported that the changes in mean Qmax from baseline were comparable between tamsulosin and silodosin, and both were not statistically different from respective baseline. There was no significant reduction in prostate volume after 12-week of therapy in either group. In neither group, other uroflowmetry parameters changed significantly with treatment. However, they suggested that these findings need confirmation in a larger and longer-term study.

Regarding tolerability in our study, both treatments were well-accepted as assessed by clinical and laboratory parameters. The events encountered were both mild in nature and transient. The most specific adverse reaction was retrograde ejaculation found in 3 out of 26 subjects in silodosin group (and none in tamsulosin group) and dizziness or postural hypotension found in 3 subjects out of 27 in tamsulosin group (and none in silodosin group). However, possibly because of the limited sample size, these differences in counts were not statistically significant.

It is to be noted that in our study we assessed sexual function quality of the subjects using a separate 6-item questionnaire that forms a component of the broader IPSS scoring. This was done as part of the primary outcome measure. The quality showed significant downgrading in silodosin group compared with the baseline value and also when compared to tamsulosin at study end. Literature reports similar findings. The noninferiority trial by Yu et al.[13] reported that patients receiving silodosin had a significantly higher incidence of abnormal ejaculation (9.7% vs. tamsulosin 1.0%; P = 0.009).

However, in our study, if subjects complained specifically of abnormal ejaculation, this was recorded as an adverse event. It is not surprising that a significant number of sexually active men with LUTS/BPH consult physicians for erectile dysfunction and other genitourinary difficulties. Although sexual activity normally diminishes with age, impaired sexual performance remains an undesirable adverse effect of BPH management. Alfa1A-adrenoceptors are widely distributed in epididymis, vas deferens, seminal vesicle, prostate gland, prostatic urethra and bladder neck. Abnormal ejaculation is a class effect of treatment with α1-receptor blockers, although it is rarely serious enough to prompt patients to withdraw from treatment (the risk of ejaculation disorders due to α1-blocker therapy for BPH is much lower than that from surgical intervention for BPH). We have interpreted changes in ejaculatory function as an adverse event. In contrast, it has also been viewed that changes in ejaculation are an indirect indicator of efficacy. That is, the greater the incidence of ejaculatory changes, the more likely that the patient is undergoing medical resection of the prostate. However, to date, this view is not universally accepted.

It is also to be noted that there is a lack of uniform definition of ejaculatory function and dysfunction. The term retrograde ejaculation covers a broad spectrum of patient reported events of abnormal ejaculation, including the absence of seminal emission, reduced ejaculate volume, and reduced ejaculation force. We assume that the relaxation of the bladder neck muscle secondary to α1A-receptor blockade leads to backflow of seminal fluid from the prostatic urethra into the bladder. High incidences of abnormal ejaculation were reported with silodosin during the development stage of the drug in Japan and USA–to the tune of 22-28%.[5,20] We encountered a similar incidence of 23% in the silodosin arm, but none in the tamsulosin arm.

We did not have a formal pharmacoeconomic component in this study, but a question of cost comparison is natural in this context. Since BPH is a chronic condition, its treatment would be for an indefinite period. Furthermore, since both drugs belong to the same therapeutic class, monitoring of treatment (e.g., periodic USG evaluation and PSA measurement) would have to be on a similar pattern. Finally, both drugs are given once daily. Therefore comparison of the cost of treatment with the two drugs becomes essentially a comparison of unit costs (tamsulosin 400 mcg vs. silodosin 8 mg), which is higher for silodosin, considering the commonly available brands in the Indian market.

The present study has its share of limitations. The treatment period was adequate to assess symptom relief but too short for any potential reduction of prostate size to occur. We depended on commercially marketed formulations and did not have access to logistical facilities required to achieve double blinding. Although we took standard precautions like allocation concealment and secure randomization code, it was not possible to conceal the identity of the treatment from the attending investigator as the two capsules were not identical in appearance. The patients however were not told about the identity of the capsules or their manufacturer. There is always the possibility that with single blinding there might be bias in subjective assessment by the attending investigator. Also for logistical reasons, there was no arrangement to assess for persistence of adverse events beyond the study period.

Nevertheless, despite the above limitations, it can be said that silodosin is comparable to tamsulosin in the treatment of symptomatic BPH in Indian men. Both offer symptom relief without affecting prostate size in the short-term. Retrograde ejaculation was encountered only with silodosin and postural hypotension only with tamsulosin. This may influence the choice of drug – silodosin for elderly patients and tamsulosin for comparatively younger sexually active men. Further clinical studies, of longer duration, are needed to confirm whether this comparability in the treatment of BPH is sustained in the long term.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank Dr. Rajendra Prasad Ray, Postdoctoral Trainee, Department of Urology, IPGMER, Kolkata for assistance with patient evaluation and Dr. Ratnamala Ray of Ashok Laboratory Clinical Testing Centre Private Limited, Kolkata, for guiding us with the blood tests. M/s Cipla Limited, Mumbai, donated both study drugs and reimbursed part of the cost of laboratory investigations on request. We are grateful to Dr. Jaideep Gogtay, Medical Director of Cipla, for facilitating the donation.

Footnotes

Source of Support: As acknowledged.

Conflict of Interest: No.

References

- 1.Chute CG, Panser LA, Girman CJ, Oesterling JE, Guess HA, Jacobsen SJ, et al. The prevalence of prostatism: A population-based survey of urinary symptoms. J Urol. 1993;150:85–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roehrborn CG, McConnell JD. Etiology, pathophysiology, epidemiology and natural history of benign prostatic hyperplasia. In: Walsh PC, Retik AB, Vaughan ED Jr, Wein AJ, editors. Campbell's Urology. 8th ed. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Co; 2002. pp. 1297–336. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reznicek SB. Common urologic problems in the elderly. Prostate cancer, outlet obstruction, and incontinence require special management. Postgrad Med. 2000;107:163–4. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2000.01.828. 167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaplan SA. Use of alpha-adrenergic inhibitors in treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia and implications on sexual function. Urology. 2004;63:428–34. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshida M, Homma Y, Kawabe K. Silodosin, a novel selective alpha 1A-adrenoceptor selective antagonist for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2007;16:1955–65. doi: 10.1517/13543784.16.12.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilt TJ, Mac Donald R, Rutks I. Tamsulosin for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003:CD002081. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barry MJ, Fowler FJ, Jr, O’Leary MP, Bruskewitz RC, Holtgrewe HL, Mebust WK, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol. 1992;148:1549–57. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36966-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacobsen SJ, Jacobson DJ, Girman CJ, Roberts RO, Rhodes T, Guess HA, et al. Treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia among community dwelling men: The Olmsted County study of urinary symptoms and health status. J Urol. 1999;162:1301–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oelke M, Bachmann A, Descazeaud A, Emberton M, Gravas S, Michel MC, et al. Arnhem: European Association of Urology; 2011. Guidelines on the treatment of non-neurogenic male LUTS; pp. 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshida M, Kudoh J, Homma Y, Kawabe K. Safety and efficacy of silodosin for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Clin Interv Aging. 2011;6:161–72. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S13803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamada S, Kato Y, Okura T, Kagawa Y, Kawabe K. Prediction of alpha1-adrenoceptor occupancy in the human prostate from plasma concentrations of silodosin, tamsulosin and terazosin to treat urinary obstruction in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Biol Pharm Bull. 2007;30:1237–41. doi: 10.1248/bpb.30.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chapple CR, Montorsi F, Tammela TL, Wirth M, Koldewijn E, Fernández Fernández E, et al. Silodosin therapy for lower urinary tract symptoms in men with suspected benign prostatic hyperplasia: Results of an international, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled clinical trial performed in Europe. Eur Urol. 2011;59:342–52. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu HJ, Lin AT, Yang SS, Tsui KH, Wu HC, Cheng CL, et al. Non-inferiority of silodosin to tamsulosin in treating patients with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) BJU Int. 2011;108:1843–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawabe K, Yoshida M, Homma Y. Silodosin Clinical Study Group. Silodosin, a new alpha1A-adrenoceptor-selective antagonist for treating benign prostatic hyperplasia: Results of a phase III randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study in Japanese men. BJU Int. 2006;98:1019–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marks LS, Gittelman MC, Hill LA, Volinn W, Hoel G. Rapid efficacy of the highly selective alpha1A-adrenoceptor antagonist silodosin in men with signs and symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia: Pooled results of 2 phase 3 studies. J Urol. 2009;181:2634–40. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ding H, Du W, Hou ZZ, Wang HZ, Wang ZP. Silodosin is effective for treatment of LUTS in men with BPH: A systematic review. Asian J Androl. 2013;15:121–8. doi: 10.1038/aja.2012.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marberger MJ. Long-term effects of finasteride in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. PROWESS study group. Urology. 1998;51:677–86. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lepor H, Williford WO, Barry MJ, Brawer MK, Dixon CM, Gormley G, et al. The efficacy of terazosin, finasteride, or both in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:533–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608223350801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McConnell JD, Roehrborn CG, Bautista OM, Andriole GL, Jr, Dixon CM, Kusek JW, et al. The long-term effect of doxazosin, finasteride, and combination therapy on the clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2387–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silodosin [Monograph online] [Last accessed on 2014 May 30]. Available from: http://www.drugbank.ca/drugs/DB06207 .