Abstract

Here, three novel cholesterol (Ch)/low molecular weight polyethylene glycol (PEG) conjugates, termed α, ω-cholesterol-functionalized PEG (Ch2-PEGn), were successfully synthesized using three kinds of PEG with different average molecular weight (PEG600, PEG1000 and PEG2000). The purpose of the study was to investigate the potential application of novel cationic liposomes (Ch2-PEGn-CLs) containing Ch2-PEGn in gene delivery. The introduction of Ch2-PEGn affected both the particle size and zeta potential of cationic liposomes. Ch2-PEG2000 effectively compressed liposomal particles and Ch2-PEG2000-CLs were of the smallest size. Ch2-PEG1000 and Ch2-PEG2000 significantly decreased zeta potentials of Ch2-PEGn-CLs, while Ch2-PEG600 did not alter the zeta potential due to the short PEG chain. Moreover, the in vitro gene transfection efficiencies mediated by different Ch2-PEGn-CLs also differed, in which Ch2-PEG600-CLs achieved the strongest GFP expression than Ch2-PEG1000-CLs and Ch2-PEG2000-CLs in SKOV-3 cells. The gene delivery efficacy of Ch2-PEGn-CLs was further examined by addition of a targeting moiety (folate ligand) in both folate-receptor (FR) overexpressing SKOV-3 cells and A549 cells with low expression of FR. For Ch2-PEG1000-CLs and Ch2-PEG2000-CLs, higher molar ratios of folate ligand resulted in enhanced transfection efficacies, but Ch2-PEG600-CLs had no similar in contrast. Additionally, MTT assay proved the reduced cytotoxicities of cationic liposomes after modification by Ch2-PEGn. These findings provide important insights into the effects of Ch2-PEGn on cationic liposomes for delivering genes, which would be beneficial for the development of Ch2-PEGn-CLs-based gene delivery system.

Keywords: cholesterol, polyethylene glycol, cationic liposomes, gene delivery, folate ligand

1. Introduction

Cholesterol (Ch), an essential membrane component in higher eukaryotes, modulates functions of membrane proteins and participates in several membrane trafficking and transmembrane signaling processes [1]. Ch facilitates the formation of semi-permeable barriers between cellular compartments and regulates membrane fluidity [1,2]. Ch has been widely used for liposome preparation and other lipid-based drug delivery systems [3,4]. Furthermore, the hydroxyl group in Ch can be modified with other moieties [5,6]. Poly (ethylene glycol) (PEG) cholesterol conjugates (PEG-Ch) had been developed to enhance the stability and activity of liposomes and other lipid-based drug delivery systems [7,8,9]. PEG-Ch conjugates were further modified with targeting ligands or antibodies to increase the targeting efficacy of the delivery systems [10,11,12].

As a PEG-Ch conjugate, it has been reported that the hydrophobic groups in α, ω-Ch-modified PEG (Ch2-PEGn) were capable of inserting into the hydrophobic interior of lipid bilayers or membranes [13,14,15]. High molecular weight Ch2-PEGn (PEG30000–PEG35000) had been used to prepare liposome gels [16,17] and core-shell emulsion particles [18]. However, there is no report about applying Ch2-PEGn to gene delivery up to now.

For PEG conjugates, the molecular weight of PEG had a significant effect on the properties of the drug delivery systems containing them [7,19,20,21]. PEG2000 modified polyethylenimine (PEI) was more efficient than PEG5000 modified PEI as evaluated by in vitro gene transfer [22]. PEG400 significantly enhanced fractional laser-assisted drug delivery when compared with PEG2050 and PEG3350 [23].

Therefore, the purpose of the study was to explore the potential application of novel cationic liposomes (Ch2-PEGn-CLs) containing Ch2-PEGn using three kinds of PEG with different average molecular weight (PEG600, PEG1000 and PEG2000) for gene delivery. The impacts of variation in PEG molecular weight on the properties, toxicities and gene delivery efficacies were determined. In addition, the gene delivery efficacy of Ch2-PEGn-CLs was further investigated by introduction of the targeting moiety (folate ligand) in both folate-receptor (FR) overexpressing SKOV-3 cells and A549 cells with low expression of FR.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis and Identification of Ch2-PEGn

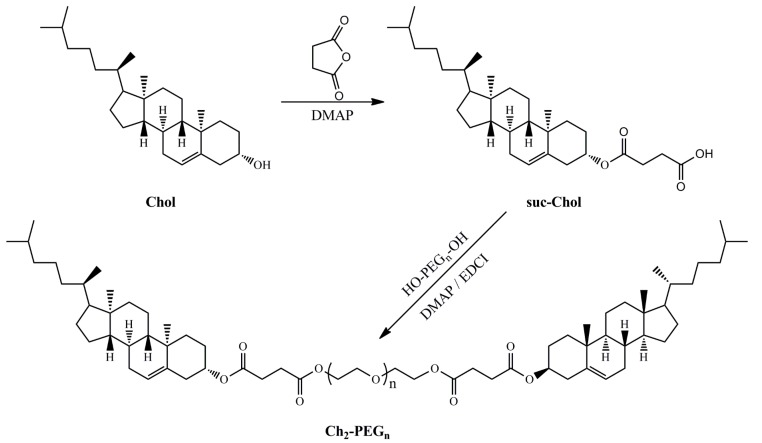

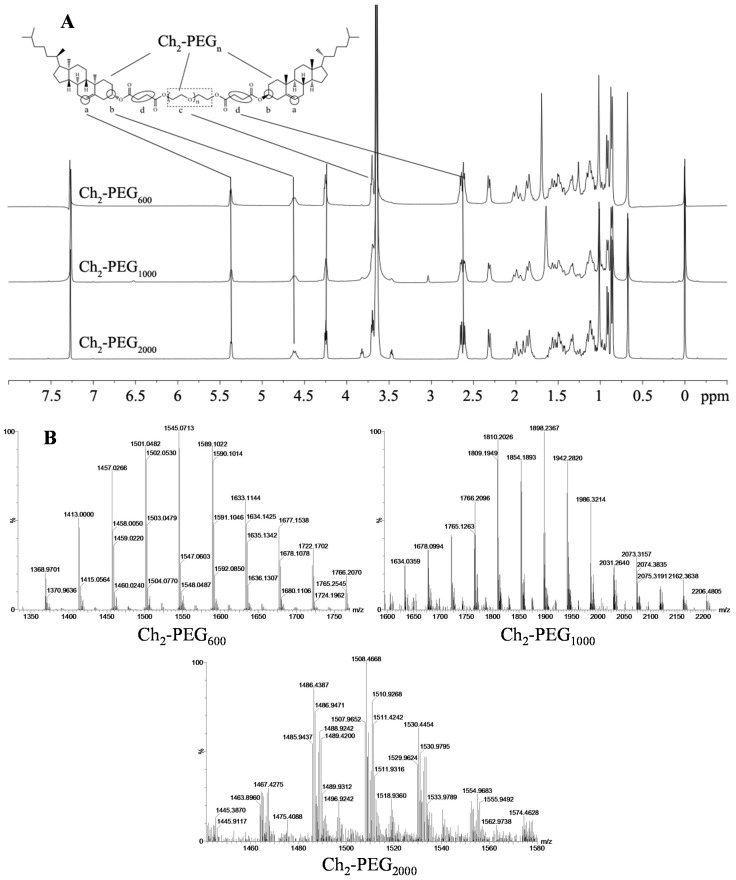

The successful synthesis of Ch2-PEGn was confirmed by 1H-NMR and mass spectra. As shown in Scheme 1, Ch2-PEGn was synthesized by esterification of succinic anhydride-cholesterol (suc-Ch) with PEG using 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) and 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethyllaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDCI) as catalysts. The 1H-NMR spectra of Ch2-PEGn were shown in Figure 1A. The principal peaks of suc-Ch and poly (ethylene glycol) (PEG) moieties were observed [8,24]. The molecular weights of Ch2-PEGn were measured by the Quadrupole-Time of Flight (Q-TOF) mass spectra as shown in Figure 1B. For Ch2-PEG600 and Ch2-PEG1000, the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) spectrums showed dominant ions at m/z 1545 and 1896. Their m/z ions were singly charged [(M + H)+]. Therefore, the measured molecular weight of Ch2-PEG600 and Ch2-PEG1000 were 1544 and 1895 Da respectively after subtracting H+. For Ch2-PEG2000, the m/z values differed by 0.5 Da as z, so the number of charges was equal to 2. The m/z ions were doubly charged [(M + 2H)2+]. The measured molecular weight of Ch2-PEG2000 was 3012 Da [(1508 − 2) × 2]. All the calculated molecular weights were consistent with the true molecular weights.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis route of Ch2-PEGn conjugates.

Figure 1.

1H-NMR and mass spectra of Ch2-PEGn. (A) 1H-NMR spectra (400 MHz) of Ch2-PEGn in CDCl3; (a,b) 6- and 3-position protons in Chol; (c) protons of methylene in PEG and (d) methylene proton of succinyl group. The principal proton peaks of Chol-suc and PEG were found in Ch2-PEGn; (B) Mass spectra of Ch2-PEGn. The m/z ions of Ch2-PEG600 and Ch2-PEG1000 are singly charged molecular-related ions; the m/z ions of Ch2-PEG2000 are doubly charged molecular-related ions. The measured molecular weight of Ch2-PEG600, Ch2-PEG1000 and Ch2-PEG2000 were 1544, 1895 and 3012 Da, respectively.

The melting points and appearances of Ch2-PEGn were summarized in Table 1. Three kinds of Ch2-PEGn had different melting points, which might impact the film-forming property of the mixed lipids and therefore influence the stability of cationic liposomes.

Table 1.

The melting points and appearances of Ch2-PEGn. The melting point was recorded as the midpoint value in the melting temperature range to facilitate comparison.

| Samples | Melting Point (°C) | Appearance (25 °C) |

|---|---|---|

| PEG600 → Ch2-PEG600 | 20 → 33 (↑) | Clear liquid → Clear semi-solid |

| PEG1000 → Ch2-PEG1000 | 33 → 40 (↑) | White paste → Clear solid |

| PEG2000 → Ch2-PEG2000 | 52 → 47.5 (↓) | White flake → White powder |

2.2. Physicochemical Properties of Ch2-PEGn-CLs

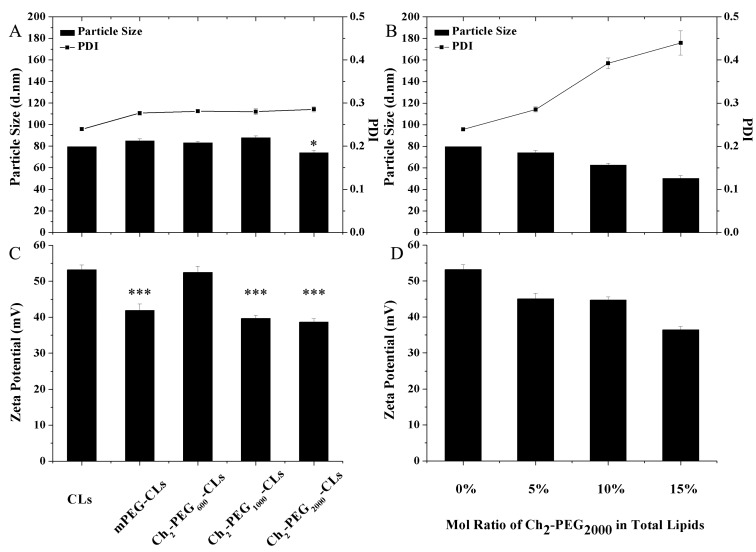

The particle size and polydispersity index (PDI) of Ch2-PEGn-CLs were shown in Figure 2A. There were no significant differences of the particle size and PDI when comparing Ch2-PEG600-CLs and Ch2-PEG1000-CLs with mPEG-CLs (CLs modified by mPEG2000-suc-Ch). However, the particle size of Ch2-PEG2000-CLs (74 nm) was significantly smaller than those of Ch2-PEG600-CLs and Ch2-PEG1000-CLs (p < 0.05). It was considered that the size decrease of Ch2-PEG2000-CLs might be attributed to the introduction of Ch2-PEG2000, which anchored into the liposomal bilayer by Ch segments [25,26] and extended the PEG chain on the surface of the liposome. The PEG chain compressed the liposomal particle [22], and therefore reduced the particle size. Then the effect of Ch2-PEG2000 on particle size was further studied. As shown in Figure 2B, the particle size of Ch2-PEG2000-CLs gradually decreased with a higher polydispersity when the molar ratio of Ch2-PEG2000 increased. Due to the high curvature and micellar preference of the large hydrophilic PEG chain, it was challenging to stably integrate high molar ratio Ch2-PEGn into liposomal bilayer [27]. Therefore, 5 mol% Ch2-PEG2000 was the optimal molar ratio.

Figure 2.

Particle size, PDI and zeta potential of Ch2-PEGn-CLs (Mean ± SD, n = 3, * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001). (A,C) Particle size, PDI, and zeta potential of Ch2-PEGn-CLs, CLs (normal cationic liposomes without PEG introduction) and mPEG-CLs; (B,D) The effect of molar ratio of Ch2-PEG2000 on the particle size, PDI and zeta potential of Ch2-PEG2000-CLs.

The zeta potentials of Ch2-PEG1000-CLs and Ch2-PEG2000-CLs were significantly lower than that of Ch2-PEG600-CLs as seen in Figure 2C (p < 0.001). It suggested that Ch2-PEG1000 and Ch2-PEG2000 could shield the electric charge of cationic liposomes. Therefore, they were good candidates like mPEG2000-suc-Ch for preparing long-circulating or stealth liposomes. The zeta potential of Ch2-PEG600-CLs was close to CLs (Figure 2C), which was consistent with the previous report that low molecular weight PEG did not effectively shield the positive charge of cationic particles [19]. The potential impact of molar ratio of Ch2-PEG2000 on zeta potentials was also studied. As shown in Figure 2D, 15 mol % was the most efficient ratio in reducing zeta potential. Similar zeta potential values were found with 5 and 10 mol % Ch2-PEG2000.

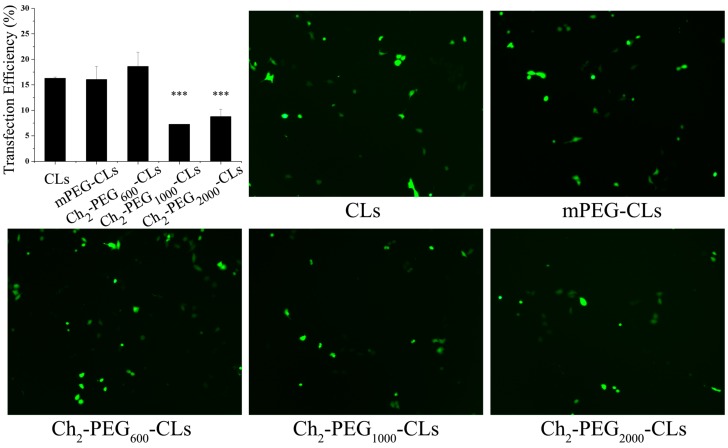

2.3. Gene Transfection Efficiencies of Ch2-PEGn-CLs

Different types of cationic liposomes were evaluated in gene transfection efficiencies by comparison. As shown in Figure 3, Ch2-PEG600-CLs had slightly higher transfection efficiency than CLs and mPEG-CLs, but there were no significant differences. In contrast, the transfection efficiencies of Ch2-PEG1000-CLs and Ch2-PEG2000-CLs were significantly lower than that of Ch2-PEG600-CLs (p < 0.001). The higher zeta potential of Ch2-PEG600-CLs (Figure 2C) than the other Ch2-PEGn-CLs might be due to its high transfection efficiency. Therefore, zeta potential is an important parameter when applying Ch2-PEGn to gene delivery. Ch2-PEG2000-CLs, with the same zeta potential but the smaller particle size (Figure 2A), achieved a bit higher transfection efficiency than Ch2-PEG1000-CLs.

Figure 3.

Transfection efficiency and fluorescence images (200×) of Ch2-PEGn-CLs (mean ± SD, n = 3, *** p < 0.001).

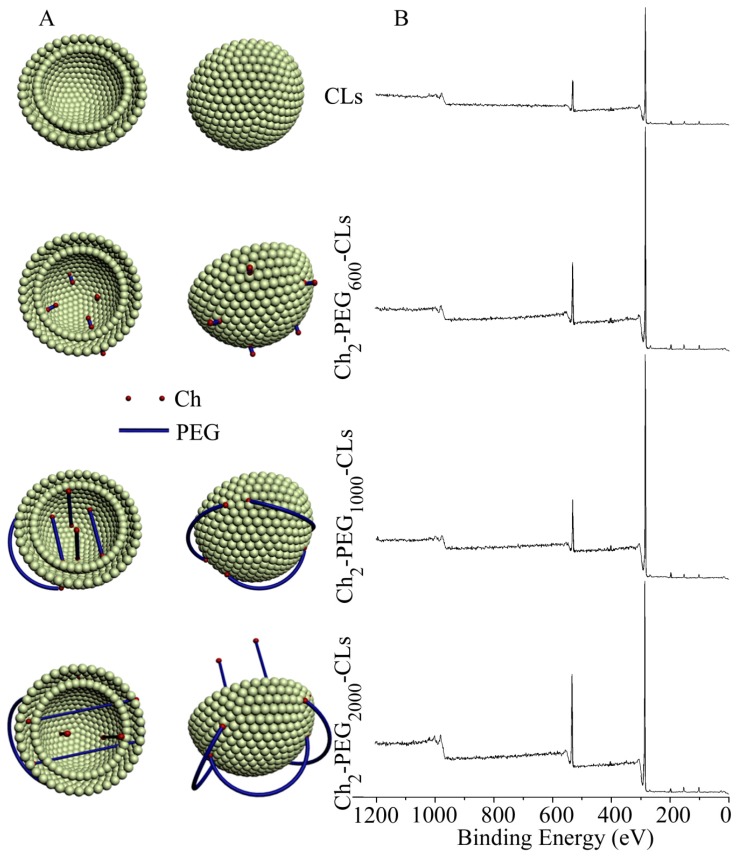

To further explain the differences in zeta potential and transfection efficacies of several cationic liposomes consisting of Ch2-PEGn with different molecular weights, XPS analysis was carried out of various Ch2-PEGn-CLs and the schematic diagrams are shown in Figure 4. More oxygen atoms from ethylenedioxy groups of PEG were found on the surface of CLs with the increase of PEG molecular weight as shown in Figure 4B. The presence of PEG chains outside of CLs had the potential to shield the electronic charge, and decrease the zeta potential as shown in Figure 4A. However, Ch2-PEG600-CLs, with the shorter PEG chain, which could not shield the surface charge of liposomes, had a significant higher zeta potential than Ch2-PEG1000-CLs and Ch2-PEG2000-CLs, which resulted in the increased transfection efficiency. The zeta potentials of Ch2-PEG1000-CLs and Ch2-PEG2000-CLs were comparable and might be due to the saturation of the shielding effect. Ch2-PEG1000-CLs and Ch2-PEG2000-CLs also showed comparable transfection efficiency due to similar zeta potential.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram and XPS analysis of Ch2-PEGn-CLs. (A) Ch segments of Ch2-PEGn anchored into the lipid bilayer of CLs. Due to the short PEG chain, Ch2-PEG600 did not effectively shield the charge of CLs. Ch2-PEG1000 and Ch2-PEG2000 decreased the positive charge by covering the surface of CLs. With longer PEG chains, Ch2-PEG2000 compressed the liposomal particle and therefore Ch2-PEG2000-CLs showed a smaller particle size; (B) XPS analysis demonstrated that more PEG segments were located on the surface of liposomes when PEG molecular weight increased.

2.4. Gene Transfection Efficiencies of F-Ch2-PEGn-CLs with Introduction of a Folate Ligand

The gene delivery efficacy of Ch2-PEGn-CLs was further examined by addition of a targeting moiety (folate ligand) in both folate-receptor (FR) overexpressing SKOV-3 cells and A549 cells with low expression of FR.

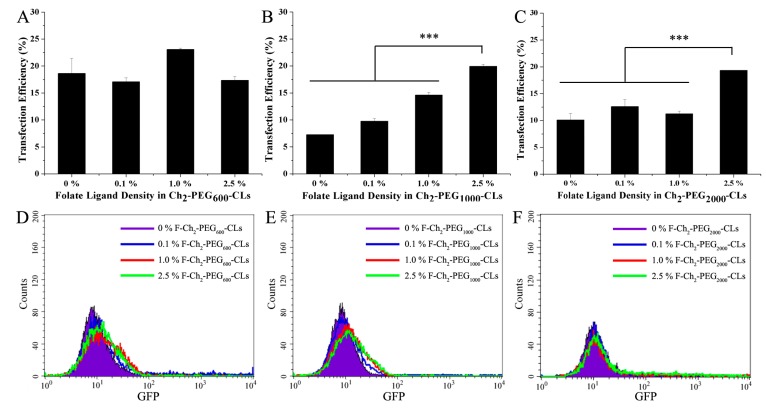

We previously demonstrated that SKOV-3 cells overexpress the folate receptor alpha [24]. The effects of folate ligand and its density on the transfection efficiencies of Ch2-PEGn-CLs in SKOV-3 cells are shown in Figure 5. For Ch2-PEG600-CLs, the transfection efficacy was close to 19% without folate ligand modification. There was no special trend with the change of folate ligand ratio for F-Ch2-PEG600-CLs. Their transfection efficacies were all around 20% (Figure 5A,D). In contrast, transfection efficiencies of F-Ch2-PEG1000-CLs were significantly elevated with the increase of folate ligand density (p < 0.001, shown in Figure 5B,E). About 20% cells were transfected with 2.5% F-Ch2-PEG1000-CLs, which was almost 3-fold of that for Ch2-PEG1000-CLs without folate modification. Similarly, 2.5% F-Ch2-PEG2000-CLs had higher transfection efficiency than other Ch2-PEG1000-CLs as shown in Figure 5C,F. Therefore, the optimal ligand density should be screened when various PEG with different molecular weight was employed for preparing CLs in the future.

Figure 5.

The effect of folate ligand densities in F-Ch2-PEGn-CLs on transfection efficiencies (mean ± SD, n = 3, *** p < 0.001). (A–C) The transfection efficiencies of F-Ch2-PEG600-CLs, F-Ch2-PEG1000-CLs and F-Ch2-PEG2000-CLs. 0%: Ch2-PEGn-CLs without folate ligand modification; 0.1%, 1.0% and 2.5%: Ch2-PEGn-CLs modified by 0.1, 1.0 and 2.5 mol % F-suc-PEG2000-Chol in total lipids, respectively; (D–F) The flow cytometry results of transfection by F-Ch2-PEGn-CLs.

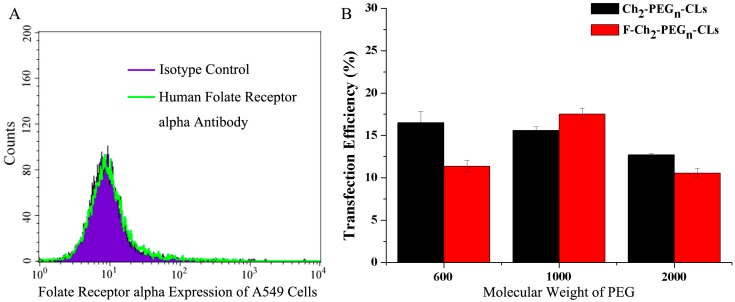

As shown in Figure 6A, folate receptor alpha is not expressed on A549 cells by folate receptor assay as previously reported [24]. When Ch2-PEGn-CLs and F-Ch2-PEGn-CLs were used to transfect A549 cells, F-Ch2-PEGn-CLs did not significantly increase the transfection efficiency of Ch2-PEGn-CLs as shown in Figure 6B.

Figure 6.

Folate receptor alpha expression and transfection efficiency on A549 cells. (A) Folate receptor alpha expression on A549 cells by flow cytometry and (B) The transfection efficiencies of Ch2-PEGn-CLs and F-Ch2-PEGn-CLs on A549 cells.

2.5 Cytotoxicity Evaluation

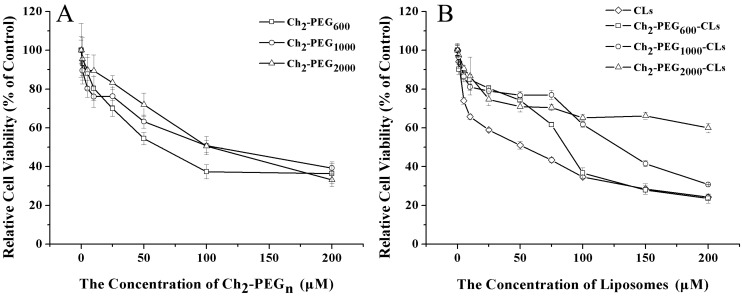

The cytotoxicities of Ch2-PEGn on SKOV-3 cells were shown in Figure 7A. The toxicities were concentration-dependent. After treatment for 24 h, the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) for Ch2-PEG600, Ch2-PEG1000 and Ch2-PEG2000 on SKOV-3 cells were about 78, 145 and 127 μM, respectively. Ch2-PEG600 was slightly more toxic to SKOV-3 cells than the other. However, even for Ch2-PEG600, the IC50 value was higher than other PEG-lipid conjugates that have been extensively used for drug and gene delivery [24,28]. Therefore, Ch2-PEGn may be one kind of safe material for gene delivery.

Figure 7.

Cytotoxicity of Ch2-PEGn and Ch2-PEGn-CLs on SKOV-3 cells by the MTT assay (Mean ± SD, n = 4–6). (A) IC50 values for Ch2-PEG600, Ch2-PEG1000 and Ch2-PEG2000 were about 78, 145 and 127 μM, respectively; (B) IC50 values for CLs, Ch2-PEG600-CLs, Ch2-PEG1000-CLs and Ch2-PEG2000-CLs were about 38, 100, 143 and 302 μM, respectively. The cytotoxicity of CLs was reduced by introducing Ch2-PEGn into Ch2-PEGn-CLs.

The cytotoxicities of Ch2-PEGn-CLs on SKOV-3 cells were shown in Figure 7B. The cytotoxicities gradually decreased with the increase of PEG molecular weight. The IC50 values for CLs, Ch2-PEG600-CLs, Ch2-PEG1000-CLs and Ch2-PEG2000-CLs were about 38, 100, 143 and 302 μM, respectively. 5 mol % Ch2-PEGn significantly enhanced the safety of cationic liposomes when compared with CLs (p < 0.001). Therefore, employing Ch2-PEGn in preparation was an effective way to reduce the cytotoxicity of cationic liposomes.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Materials

Cholesterol (Ch) was obtained from Bio Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Poly (ethylene glycol) (PEG) [molecular weight 600 (PEG600), molecular weight 1000 (PEG1000) and molecular weight 2000 (PEG2000)] and 3-(4, 5-Dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2, 5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). 1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDCI) was provided by Accela ChemBio Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) was obtained from AstaTech Pharma. Co., Ltd. (Chengdu, Sichuan, China). 1, 2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane (chloride salt) (DOTAP) was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids Inc. (Alabaster, AL, USA). Folate-PEG-succinyl-cholesterol conjugate (F-PEG2000-suc-Ch) and mPEG-succinyl-cholesterol conjugate (mPEG2000-suc-Ch) were synthesized and purified in the same procedures as those recorded in our previous publications [8,24]. Green fluorescent protein plasmid DNA (pDNA) was extracted according to the EndoFree Plasmid Purification Handbook (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). All the other reagents and solvents were of analytical grade and were used without further purification except for chloroform used for cationic liposomes preparation.

3.2. Synthesis and Identification of Ch2-PEGn

3.2.1. Synthesis of Ch2-PEGn

α, ω-Ch-modified PEGs (Ch2-PEGn) were synthesized according to Scheme 1. Firstly, Ch succinic anhydride ester (suc-Ch) was synthesized as described before [8]. In brief, Ch, succinic anhydride and DMAP were dissolved in dichlormethane and stirred for 48 h at room temperature. After removing the solvent, the crude product was washed by acetic acid. White suc-Ch was obtained. Secondly, PEG (PEG600, PEG1000, or PEG2000), suc-Ch, DMAP and EDCI were dissolved in chloroform. The mixture was refluxed for 72 h, concentrated under vacuum, and purified on a silica-gel column eluting with dichlormethane and methanol. Ch2-PEG600, Ch2-PEG1000 and Ch2-PEG2000 were obtained.

3.2.2. 1H-NMR and Mass Spectra of Ch2-PEGn

1H-NMR spectra of Ch2-PEGn were recorded on a Bruker ADVANCEIII spectrometer (400MHz) (Billerica, MA, USA) at room temperature. Ch2-PEG600, Ch2-PEG1000 and Ch2-PEG2000 were dissolved in CDCl3 with tetramethylsilane as the internal standard. The mass spectra of Ch2-PEGn were measured using a Waters Q-TOF Premier (Milford, MA, USA) equipped with ion spray source and N2 as nebulization gas.

3.2.3. Melting Point and Appearances

Melting points of Ch2-PEGn, PEG1000, PEG2000, mPEG2000-suc-Ch, suc-Ch and Ch were determined using SGW X-4 melting point apparatus (Shanghai Precision & Scientific Instrument CO., LTD., Shanghai, China). The appearances of the materials were recorded.

3.3. Preparation and Characterization of Cationic Liposomes

3.3.1. Preparation of Liposomes

Ch2-PEGn-CLs were prepared by film dispersion method as described before [29]. In brief, DOTAP, Ch and Ch2-PEGn (Ch2-PEG600, Ch2-PEG1000 or Ch2-PEG2000) at different molar ratios were dissolved in chloroform. Then the organic solvent was removed from the lipids solution using a Büchi rotary evaporator. A thin film was formed and further dried under high vacuum for 6 h at room temperature. The lipid film was hydrated with 5% (w/v) glucose solution and sonicated by a VCX130 Vibra-Cell (Sonics & Materials Inc., Newtown, CT, USA) until a translucent lipid suspension was obtained. Ch2-PEGn-CLs were formed. They were passed through a 0.22 μm Millipore microporous membrane and stored at 4 °C until use.

CLs and mPEG-CLs (served as controls), folate modified Ch2-PEGn-CLs (F-Ch2-PEGn-CLs, active targeted CLs) were prepared in the same way. CLs were made of DOTAP and Ch. mPEG-CLs were composed of DOTAP, Ch and mPEG2000-suc-Ch. F-Ch2-PEGn-CLs were consisted of F-PEG2000-suc-Ch, DOTAP, Ch and Ch2-PEGn.

3.3.2. Size and Zeta Potential Determination

The mean particle size and zeta potential of the liposomes were measured by a Zetasizer Nano ZS ZEN 3600 (Malvern Instruments, Ltd., Malvern, Worcestershire, UK). The mean particle size was determined at a fixed angle of 173°. The zeta potential of 5 mg/mL liposome at pH 6.0 was automatically calculated from the electrophoretic mobility at 25 °C. All the experiments were performed in triplicate.

3.4. Cell Culture

Human ovarian carcinoma SKOV-3 cell line and human lung carcinoma A549 cell line were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Cells were cultured as a monolayer in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagles’s Medium (DMEM, Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) or Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium (RPMI)-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, l-glutamine (2 mmol/L), penicillin (100 units/mL) and streptomycin (100 μg/mL) in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

3.5. In Vitro Transfection Experiments

SKOV-3 or A549 cells were seeded on Costar 6-well plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) at a density of 1.5 × 105 cells per well and cultured in DMEM medium or RPMI-1640 as described before [24]. 30 min prior to transfection, the culture medium was replaced by 800 μL serum-free DMEM or RPMI-1640 in each well. Then Ch2-PEGn-CLs/pEGFP, CL/pEGFP, mPEG-CLs/pEGFP or F-Ch2-PEGn-CLs/pEGFP complexes (200 μL, containing 1 μg pDNA) was added to the wells respectively. Three wells were used for each lipoplex. After incubating for 5–6 h, cell culture medium was changed to DMEM or RPMI-1640 with serum and the cells were incubated for another 42–43 h. The transfected cells were observed under an inverted research microscope, Eclipse Ti (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Then they were trypsinized with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA, centrifuged and resuspended with PBS. The cell suspensions were analyzed by a FACS Calibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) to determine the transfection efficiency of the complexes.

3.6. Cytotoxicity of Ch2-PEGn and Ch2-PEGn-CLs

Cytotoxicity of Ch2-PEGn was evaluated in the SKOV-3 cell line by MTT assay as described previously [30]. Briefly, cells were seeded on 96-well plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) in 100 μL medium at a density of 5 × 103 cells per well. After overnight incubation, another 100 μL Ch2-PEGn solutions at various concentrations (ranged from 1 to 200 μM) were added to the wells. The cells were incubated for another 24 h. Then 20 μL MTT solution (5 mg/mL in saline) was added to each well. After culturing at 37 °C for 4 h, the medium was removed. 160 μL DMSO was added to each well to dissolve formazan crystals. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm on a Multiskan MK3 microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Untreated cells were used as controls. The relative cell viability compared with control was calculated based on the following equation: Relative cell viability (%) = (Atreated/Acontrol) × 100.

3.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s Independent-Samples t-Test on SPSS (V 19.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). All the statistical tests were two-sided. p < 0.05 was considered as statistical significant difference.

4. Conclusions

In this manuscript, a series of Ch2-PEGn at different PEG molecular weights (600, 1000 and 2000) were successfully synthesized. Ch2-PEGn-CLs containing various Ch2-PEGn presented different particle size, zeta potential and in vivo transfection efficacy, and Ch2-PEG600-CLs exhibited the strongest GFP expression in SKOV3 cells due to its highest zeta potential. However, Ch2-PEG600-CLs also had the highest in vitro cytotoxicity. After introduction of a folate ligand, the targeting efficacies and optimized ligand densities of F-Ch2-PEGn-CLs still depended on the molecular weights of PEG. In sum, Ch2-PEGn-CLs are promising carriers for gene delivery. The current work demonstrates the possibility of utilizing Ch2-PEGn for gene delivery, and a corresponding systematic investigation of this study would benefit the future development of Ch2-PEGn-CLs-based gene delivery systems.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China Grant 2010CB529900 and the National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 81123003, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities 2013SCU04A19.

Author Contributions

Cui-Cui Ma and Zhi-Yao He performed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the paper; Shan Xia, Li-Wei Hui and Han-Xiao Qin performed the experiments; Ke Ren and Jun Zeng wrote the paper; Ming-Hai Tang contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools; Xiang-Rong Song conceived and designed the experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ikonen E. Cellular cholesterol trafficking and compartmentalization. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008;9:125–138. doi: 10.1038/nrm2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lingwood D., Simons K. Lipid rafts as a membrane-organizing principle. Science. 2010;327:46–50. doi: 10.1126/science.1174621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.He Z.Y., Wei X.W., Luo M., Luo S.T., Yang Y., Yu Y.Y., Chen Y., Ma C.C., Liang X., Guo F.C., et al. Folate-linked lipoplexes for short hairpin RNA targeting Claudin-3 delivery in ovarian cancer xenografts. J. Control. Release. 2013;172:679–689. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Porter C. J., Trevaskis N. L., Charman W.N. Lipids and lipid-based formulations: Optimizing the oral delivery of lipophilic drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007;6:231–248. doi: 10.1038/nrd2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma Q., Li B., Yu Y., Zhang Y., Wu Y., Ren W., Zheng Y., He J., Xie Y., Song X., et al. Development of a novel biocompatible poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(γ-cholesterol-l-glutamate) as hydrophobic drug carrier. Int. J. Pharm. 2013;445:88–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang J., Zhang L., Liu Y., Zhang Q., Qin Y., Yin Y., Yuan W., Yang Y., Xie Y., Zhang Z., et al. Synergistic targeted delivery of payload into tumor cells by dual-ligand liposomes co-modified with cholesterol anchored transferrin and TAT. Int. J. Pharm. 2013;454:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu L., Wempe M.F., Anchordoquy T.J. The effect of cholesterol domains on PEGylated liposomal gene delivery in vitro. Ther. Deliv. 2011;2:451–60. doi: 10.4155/tde.11.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li J.M., He Z.Y., Yu S., Li S.Z., Ma Q., Yu Y.Y., Zhang J.L., Li R., Zheng Y., He G., et al. Micelles based on methoxy poly(ethylene glycol)cholesterol conjugate for controlled and targeted drug delivery of a poorly water soluble drug. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2012;8:809–17. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2012.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu Y., He Y., Xu B., He Z., Zhang Y., Chen Y., Yang Y., Xie Y., Zheng Y., He G., et al. Self-assembled methoxy poly(ethylene glycol)cholesterol micelles for hydrophobic drug delivery. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013;102:1054–1062. doi: 10.1002/jps.23418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oba M., Miyata K., Osada K., Christie R.J., Sanjoh M., Li W., Fukushima S., Ishii T., Kano M.R., Nishiyama N., et al. Polyplex micelles prepared from omega-cholesteryl PEG-polycation block copolymers for systemic gene delivery. Biomaterials. 2011;32:652–663. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu L., Betker J., Yin H., Anchordoquy T.J. Ligands located within a cholesterol domain enhance gene delivery to the target tissue. J. Control. Release. 2012;160:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He Z.Y., Chu B.Y., Wei X.W., Li J., Edwards C.K., 3rd, Song X.R., He G., Xie Y.M., Wei Y.Q., Qian Z.Y. Recent development of poly(ethylene glycol)-cholesterol conjugates as drug delivery systems. Int. J. Pharm. 2014;469:168–178. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.04.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meier W., Hotz J., GuntherAusborn S. Vesicle and cell networks: Interconnecting cells by synthetic polymers. Langmuir. 1996;12:5028–5032. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carrion C., Domingo J.C., de Madariaga M.A. Preparation of long-circulating immunoliposomes using PEG-cholesterol conjugates: Effect of the spacer arm between PEG and cholesterol on liposomal characteristics. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2001;113:97–110. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(01)00178-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rao Z., Taguchi T. Spectroscopic studies on interactions between cholesterol-end capped polyethylene glycol and liposome. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2012;97:248–253. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diec K.H., Sokolowski T., Wittern K.P., Schreiber J., Meier W. New liposome gels by self organization of vesicles and intelligent polymers. Cosmet. Toiletries. 2002;117:55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rao Z., Inoue M., Matsuda M., Taguchi T. Quick self-healing and thermo-reversible liposome gel. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2011;82:196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2010.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perez N., Whitcombe M.J., Vulfson E.N. Surface imprinting of cholesterol on submicrometer core-shell emulsion particles. Macromolecules. 2001;34:830–836. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petersen H., Fechner P.M., Martin A.L., Kunath K., Stolnik S., Roberts C.J., Fischer D., Davies M.C., Kissel T. Polyethylenimine-graft-poly(ethylene glycol) copolymers: Influence of copolymer block structure on DNA complexation and biological activities as gene delivery system. Bioconjug. Chem. 2002;13:845–854. doi: 10.1021/bc025529v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Savic R., Luo L., Eisenberg A., Maysinger D. Micellar nanocontainers distribute to defined cytoplasmic organelles. Science. 2003;300:615–618. doi: 10.1126/science.1078192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y., Ke C.Y., Beh C.W., Liu S.Q., Goh S.H., Yang Y.Y. The self-assembly of biodegradable cationic polymer micelles as vectors for gene transfection. Biomaterials. 2007;28:5358–5368. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X., Pan S.R., Hu H.M., Wu G.F., Feng M., Zhang W., Lu X. Poly(ethylene glycol)-block-polyethylenimine copolymers as carriers for gene delivery: Effects of PEG molecular weight and PEGylation degree. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2008;84A:795–804. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haak C.S., Bhayana B., Farinelli W.A., Anderson R.R., Haedersdal M. The impact of treatment density and molecular weight for fractional laser-assisted drug delivery. J. Control. Release. 2012;163:335–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He Z., Yu Y., Zhang Y., Yan Y., Zheng Y., He J., Xie Y., He G., Wei Y., Song X. Gene delivery with active targeting to ovarian cancer cells mediated by folate receptor α. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2013;9:833–844. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2013.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heyes J., Hall K., Tailor V., Lenz R., MacLachlan I. Synthesis and characterization of novel poly(ethylene glycol)-lipid conjugates suitable for use in drug delivery. J. Control. Release. 2006;112:280–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gimpl G., Gehrig-Burger K. Probes for studying cholesterol binding and cell biology. Steroids. 2011;76:216–231. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Photos P.J., Bacakova L., Discher B., Bates F.S., Discher D.E. Polymer vesicles in vivo: Correlations with PEG molecular weight. J. Control. Release. 2003;90:323–334. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00201-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han X., Liu J., Liu M., Xie C., Zhan C.Y., Gu B., Liu Y., Feng L.L., Lu W.Y. 9-NC-loaded folate-conjugated polymer micelles as tumor targeted drug delivery system: Preparation and evaluation in vitro. Int. J. Pharm. 2009;372:125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He Z., Zheng X., Wu X., Song X., He G., Wu W., Yu S., Mao S., Wei Y. Development of glycyrrhetinic acid-modified stealth cationic liposomes for gene delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2010;397:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song X.R., Zheng Y., He G., Yang L., Luo Y.F., He Z.Y., Li S.Z., Li J.M., Yu S., Luo X., et al. Development of PLGA nanoparticles simultaneously loaded with vincristine and verapamil for treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010;99:4874–4879. doi: 10.1002/jps.22200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]