Abstract

Introduction:

Hairy cell leukemia is a rare chronic B-cell disorder that follows an indolent but progressive course. This disorder is characterized by pancytopenia, splenomegaly, bone marrow fibrosis and the presence of atypical lymphoid cells with hairy projections in peripheral blood, bone marrow and spleen. Treatment is mainly with nucleoside analog cladribine, which induces complete remission in up to 85% cases.

Materials and Methods:

This is a retrospective analysis of Hairy cell Leukemia cases diagnosed and treated in the Department of Hematology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi between 2002 and 2013. Various parameters such as clinical features, laboratory parameters including complete blood cell count, bone marrow findings, cytochemistry, immunophenotyping by flowcytometry or immunohistochemistry, treatment protocol and complications secondary to treatment and relapse were reviewed.

Results:

A total of 35 cases were diagnosed during this period of 12 years of which 27 received cladribine and went in to remission. Median follow-up duration was 26 months. 5 (18%) cases had a relapse and all relapsed cases achieved second remission with cladribine; however, there was no case of second malignancy in our cohort.

Conclusion:

Cladribine has emerged as the treatment of choice for hairy cell leukemia given that the overwhelming majority of patients achieve long-lasting complete remissions. Upon relapse, these patients could be successfully salvaged with cladribine retreatment.

Keywords: Cladribine, Hairy cell leukemia, relapse, remission

INTRODUCTION

Hairy cell leukemia (HCL) is an indolent neoplasm of small mature B lymphoid cells comprising 2% of lymphoid leukemias[1] and it occurs more frequently in men (male:female - 4:1) and mean age at diagnosis is approximately 52 years.[2] This entity, also called as leukemic reticuloendotheliosis, was initially described in 1958 by Bouroncle et al.[3] This disorder is characterized by the presence of atypical lymphoid cells with oval nuclei and abundant cytoplasm with "hairy" projections involving peripheral blood and infiltrating the bone marrow and splenic red pulp. Hairy cell leukemia follows an indolent, but progressive course in which single courses of cladribine induce high rates of complete responses (CRs).

This series of patients aims at providing an evaluation of clinical presentation, laboratory features, including morphology, cytochemistry, electron microscopy and immunophenotypic profile of all cases diagnosed as HCL with special emphasis on the response and relapse rate with cladribine therapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Thirty-five patients diagnosed and managed at Department of Hematology at a tertiary care center in North India, as HCL during a period of 12-year from January 2002 to December 2013 were evaluated. The study was approved by the Institute's Ethics Committee and done in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

A written informed consent was obtained from the patients prior to the procedures and treatment. Details that might disclose the identity of the subjects were omitted.

Presenting symptoms at diagnosis (weakness/fatigability, fever, awareness of mass, weight loss, bleeding, sweating), clinical features (splenomegaly ± hepatomegaly, lymphadenopathy, infections, transfusion requirement), complete blood cell count, differential count, peripheral blood smear examination findings and bone marrow infiltration with atypical lymphoid cells with cytoplasmic fine prolongations, cytochemistry features, bone marrow biopsy findings including reticulin fibrosis, electron microscopy findings, immunohistochemistry for annexin A1 in selected cases, flow cytometric immunophenotyping (IPT) of peripheral blood or bone marrow aspirate, types of therapy, complications and relapse rate were monitored. Of thirty five patients, diagnosis of HCL was done based on tartarate resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) cytochemistry and electron microscopy in five cases (before IPT was available) and two cases were diagnosed based on annexin A1 positivity by immunohistochemistry on bone marrow biopsy as bone marrow aspirate could not be obtained for IPT by flow cytometry and peripheral smear was pancytopenic with occasional hairy cells. In remaining twenty-eight cases, IPT data was available and analyzed.

Treatment given was cladribine 0.09 mg/kg/day for 7 days as a continuous infusion in normal saline through a central line. Antibacterial, antiviral and antifungal prophylaxis was used as per the departmental policy including tablet levofloxacin 500 mg OD, tablet aciclovir 400 mg BD and tablet fluconazole 400 mg OD. Irradiated blood products were given for the following 6 months or until complete remission, whichever was later. Blood counts, differential counts and biochemistry profile was done 3 times a week for first 3 weeks and later on once a week until normalization of counts. A second course of cladribine was given in cases of relapse or nonresponders at 6 months. The response was assessed according to National Cancer Institute criteria.[4]

RESULTS

Demography

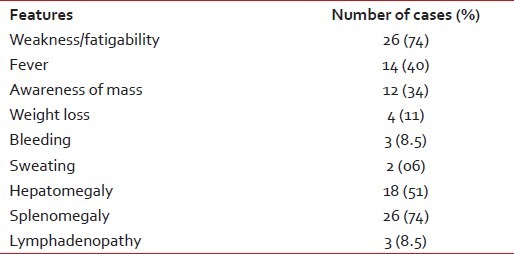

The patient age ranged from 32 to 69 years with median age at presentation being 50 years. Majority of the patients were males (32/35); male:female ratio was 10.67:1. The median duration of symptoms was 3 months (range, 1-24 months). The commonest symptom was weakness/fatigability and was noted in 74% of cases followed by fever (40%), awareness of mass (34%), weight loss (11%), bleeding (8.5%) and sweating (6%) as shown in Table 1. Transfusion requirement was observed in 31% of the patients (11/35) and of which six patients received transfusion at three or more occasions.

Table 1.

Clinical features of cases of hairy cell leukemia (total 35 cases)

On physical examination, 18 (51%) patients had hepatomegaly and 26 (74%) patients had splenomegaly. Massive splenomegaly was observed in 45% of cases. Three (8.5%) patients presented with lymphadenopathy - 2 had cervical lymphadenoapthy and 1 patient had intra-abdominal lymphadenopathy seen on radiology. Eight out of thirty-five patients (23%) had a history of infection before diagnosis - 4 had tuberculosis, 3 had pneumonia, and 1 patient had hepatitis.

Laboratory features

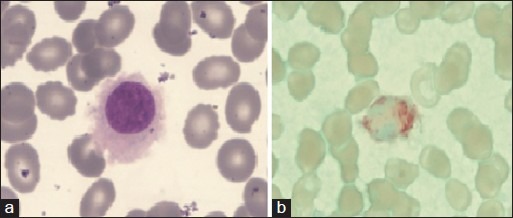

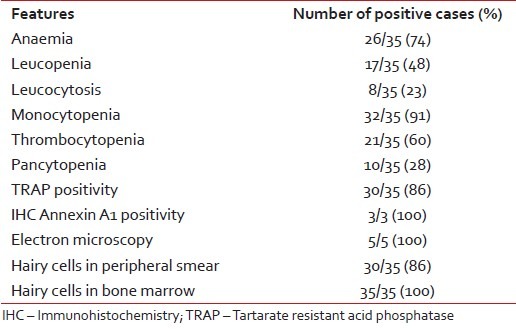

At presentation, anemia (hemoglobin [Hb] <11 g/dl) was present in 74% with median Hb of 9.0 g/dl (range, 3-14.9). Leucopenia was noted in 48% of cases with median total leucocyte count of 4.2 × 109 /L (range, 0.2-41.65) and mean platelet count was 82 × 109 /L (range, 10-222) with 60% of patients presenting with thrombocytopenia. 23% of patients had leukocytosis at presentation and pancytopenia was present in 28% cases. Monocytopenia was observed in 91% of cases. About 86% of cases showed classical hairy cells in peripheral blood while all cases showed similar cells in bone marrow. 86% of cases showed TRAP positivity [Figure 1]. In two cases where flow cytometric immunophenotyping could not be done because of repeated "dry tap," immunohistochemistry for annexin A1 helped in reaching final diagnosis. Electron microscopy was contributory in all five cases which showed characteristic elongated slender microvilli [Table 2].

Figure 1.

(a) Peripheral blood-hairy cell with round nucleus, homogenous spongy chromation with abundant pale blue cytoplasm with circumferential hair like projections (Jenner Giemsastain, ×1000) (b) tartarate resistant acid phosphatase stain showing bright red granular cytoplasmic positivity in the leukemic cells.(tartrate-treated acid phosphatase stain, ×1000)

Table 2.

Laboratory parameters of hairy cell leukemia cases

Flow cytometric immunophenotyping

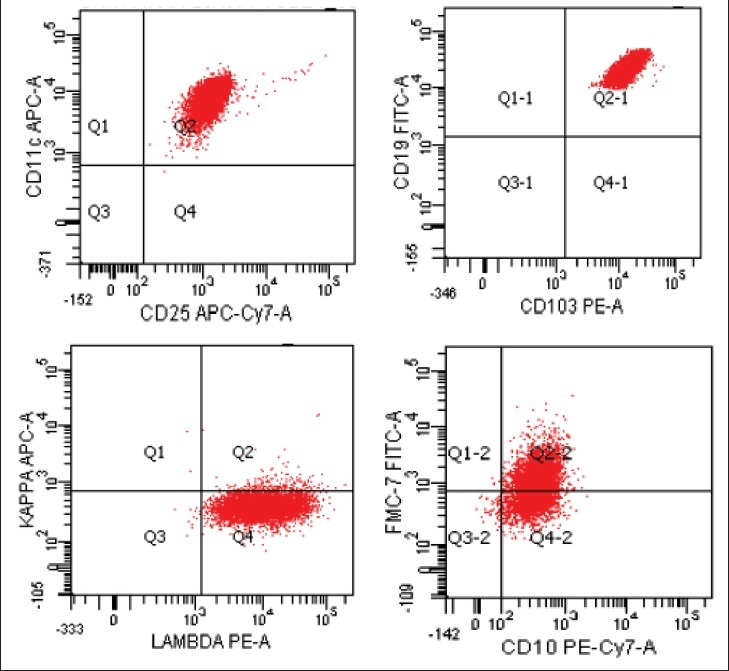

Flow cytometric data were available in 28 cases. All the cases expressed characteristic HCL phenotype such as positivity for CD19, CD20, CD11c, CD25 and CD103 [Figure 2]. Of the twenty cases evaluated for light chain restriction 35% showed kappa chain restriction while 65% of cases showed lambda chain restriction. Ten cases (36%) expressed CD10, whereas twenty-four cases (86%) demonstrated FMC7 expression. CD 79b and CD 22 expression was present in 93% and 96% of cases, respectively. Surface Immunoglobulin expression was observed in 79% of cases. Only one of the cases showed aberrant T cell markers such as CD2 and CD5.

Figure 2.

Flow cytometry dot plots in a case of hairy-cell leukemia. The neoplastic cells co-express CD11c, CD25, CD103 with lambda light chain restriction. The cells also express FMC7 in most cases and CD 10 in some cases

Treatment and follow-up

Out of 35 patients, 27 received the cladribine and eight did not due to financial constraints and subsequently lost to follow-up. Twenty-five patients (93%) had a CR after first course of cladribine; 2 patients did not respond to treatment and required a second course of treatment at 6 and 8 months and both achieved CR. All patients developed neutropenia during treatment with cladribine and were supported with recombinant growth factors. Median time to response was 3 months (range, 2-7). Median duration of follow-up was 26 months (range, 2-122). Median duration of remission was 23 months (range, 3-119). One patient out of 27 cases died due to tuberculosis after being in remission for 9 months. Five out of 27 patients (18%) relapsed after a median duration of 48 months (range, 16-102); all five patients received a second dose of cladribine and achieved CR and are alive and disease free at last follow-up. The median duration of the second remission among relapsed patients was 18 months (range, 3-50). The median overall survival was 26 months (range, 2-122) and the median disease free survival was 23 months (range, 3-119).

One out of 27 patients developed Direct Coombs' test positive autoimmune hemolytic anemia following cladribine therapy and required treatment with steroids. None of the patients on follow-up developed second malignancy.

DISCUSSION

Hairy cell leukemia is an indolent disorder which has the potential of attaining long term cure rates with current treatment modalities.[5] Our results confirm previous observations that cladribine administered to patients with HCL induces high CR rates. The present series show a median age of 50 which was similar to the recently reported Romanian study with 39 patients[6] and by Goodman et al.[1] and 53 years by Saven et al.[7] though significantly younger when compared to the French study with a median age being 67.8 years reported over a 25-year period.[2] The presenting symptoms were similar to those reported previously in western and Indian literature.[8,9] Hepatomegaly was noted in 51% of cases which was higher than that reported by an Indian (28%) and other western series,[9,10,11] In our series nearly one fourth of patients had history of infection, similar to the 30% incidence reported by Allsup and Cawley[12]

Accurate diagnosis of HCL is critical because therapy with purine analogs is associated with high CR rates and long relapse-free survival but is less effective in patients with other chronic B-cell leukemias or lymphomas.[13,14] In the majority of our cases (28/35) diagnosis was based on IPT. All 28 cases showed expression of three characteristic markers of HCL namely CD11c, CD25 and CD103. CD10, a marker for lymphoid cells with germinal center origin, has been reported positive in HCL in a relatively higher percentage compared with other small B-cell leukemias or lymphomas of nongerminal center origin. The frequency of CD10 expression in HCL in the reported studies ranged from 5% to 26%[15,16] compared to 36% in the current study. 65% of HCL cases showed Lambda restriction while remaining 35% had Kappa restriction. Other series show nearly equal distribution of Kappa and Lambda light chain restriction in HCL cases.[9] There are rare reports of CD5, CD23 expression in HCL cases, only one of our patients had aberrant expression of CD5 and CD2.[15]

According to National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, systemic symptoms, splenic discomfort, recurrent infections, cytopenias (Hb <12 g/dL, absolute neutrophil count <1000/μL and platelet count <100 × 103 /μL) are indications for treatment in a case of HCL. Asymptomatic patients may be managed by close observation ("watch and wait" approach) until indication develops. When indicated, treatment should be with either of purine analogues. In general, cladribine should be avoided in patients with active life-threatening infections or recurrent (chronic) infections.[17] Our patients were managed as per NCCN guidelines.

The overall response rate in the current study is similar to those reported previously[8,13,14,18] though some other studies have reported no responses in 11-13% of patients.[19,20,21]

The 18% rate of relapse reported in our study is lower than reported in other series which ranged from 27% to 39%,[13,22] reasons for which are unknown. One patient (4%) developed Direct Coombs' test positive autoimmune hemolytic anemia following cladribine therapy, hence close monitoring for acute fall in hemoglobin after starting cladribine should be done. None of the patients on follow-up developed second malignancy in our series, however, the incidence of second malignancies reported is as high as 22% as brought out by Goodman et al.[18] and 8% by Saven et al.[7] These studies reported a median time from diagnosis of the second cancer to cladribine therapy of 77 months (range, 1-440 months). However, median follow-up in the present study was 26 months (range, 2-122) and these patients need to be further followed-up to know the exact incidence of second malignancy.

Recently, Tiacci et al. in their landmark study, identified the BRAF V600E mutation by whole-exome sequencing and concluded that BRAF V600E mutation qualified as a disease-defining genetic event in HCL as it was present in 100% of HCL patients. Analysis of BRAF mutations serves as a potential new diagnostic tool to distinguish HCL from other B-cell lymphomas with similar clinical and morphologic features, such as the HCL variant and splenic marginal zone lymphoma. This distinction is clinically relevant, since HCL, but not HCL-like disorders, responds to therapy with interferon or purine analogues.[23] This was not undertaken in our study. BRAF protein plays a major role in regulating cell survival, proliferation, and differentiation. BRAF inhibitor, vemurafenib, has shown a good response in resistant HCL cases. Better toxicity profile and a short time to response with deeper response provide a strong rationale to explore BRAF inhibition in HCL.[24,25]

CONCLUSION

Hairy cell leukemia is a rare type of leukemia, sometimes difficult to diagnose, which may be considered in the presence of pancytopenia associated with splenomegaly, bone marrow fibrosis, presence of atypical lymphoid cells with irregular cytoplasm projections in peripheral blood, bone marrow and spleen and unique immunophenotypic features. Cladribine is the best available option for these patients and leads to high CR rates in Indian patients as first-line and second line therapy. However in resistant HCL cases, BRAF inhibitor, vemurafenib, appears to be a promising targeted therapy in the future.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goodman GR, Bethel KJ, Saven A. Hairy cell leukemia: An update. Curr Opin Hematol. 2003;10:258–66. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200307000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malfuson JV, Gisserot O, Cremades S, Doghmi K, Fagot T, Souleau B, et al. Hairy-cell leukemia: 30 cases and a review of the literature. Ann Med Interne (Paris) 2003;154:435–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouroncle BA, Wiseman BK, Doan CA. Leukemic reticuloendotheliosis. Blood. 1958;13:609–30. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheson BD, Sorensen JM, Vena DA, Montello MJ, Barrett JA, Damasio E, et al. Treatment of hairy cell leukemia with 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine via the group C protocol mechanism of the national cancer institute: A report of 979 patients. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3007–15. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.9.3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnston JB, Grever MR. Hairy cell leukemia. In: Greer JP, List AF, editors. Wintrobe's Clinical Hematology. 13th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014. pp. 1929–50. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaman AM. Hairy cell leukemia - a rare type of leukemia. A retrospective study on 39 patients. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2013;54:575–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saven A, Burian C, Koziol JA, Piro LD. Long-term follow-up of patients with hairy cell leukemia after cladribine treatment. Blood. 1998;92:1918–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffman MA. Clinical presentations and complications of hairy cell leukemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2006;20:1065–73. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galani KS, Subramanian PG, Gadage VS, Rahman K, Ashok Kumar MS, Shinde S, et al. Clinico-pathological profile of hairy cell leukemia: Critical insights gained at a tertiary care cancer hospital. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2012;55:61–5. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.94858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Golomb HM, Catovsky D, Golde DW. Hairy cell leukemia: A clinical review based on 71 cases. Ann Intern Med. 1978;89:677–83. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-89-5-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burke JS, Byrne GE, Jr, Rappaport H. Hairy cell leukemia (leukemic reticuloendotheliosis). I. A clinical pathologic study of 21 patients. Cancer. 1974;33:1399–410. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197405)33:5<1399::aid-cncr2820330526>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allsup DJ, Cawley JC. The diagnosis and treatment of hairy-cell leukaemia. Blood Rev. 2002;16:255–62. doi: 10.1016/s0268-960x(02)00044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jehn U, Bartl R, Dietzfelbinger H, Haferlach T, Heinemann V. An update: 12-year follow-up of patients with hairy cell leukemia following treatment with 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine. Leukemia. 2004;18:1476–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tallman MS. Current treatment strategies for patients with hairy cell leukemia. Rev Clin Exp Hematol. 2002;6:389–400. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-0734.2002.00305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen YH, Tallman MS, Goolsby C, Peterson L. Immunophenotypic variations in hairy cell leukemia. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;125:251–9. doi: 10.1309/PMQX-VY61-9Q8Y-43AR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jasionowski TM, Hartung L, Greenwood JH, Perkins SL, Bahler DW. Analysis of CD10+ hairy cell leukemia. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003;120:228–35. doi: 10.1309/QVJD-31TE-G9UJ-18BQ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Non Hodgkin's Lymphoma Version 3; 2014. [Last accessed on 2014 Aug 18]. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nhl.pdf .

- 18.Goodman GR, Burian C, Koziol JA, Saven A. Extended follow-up of patients with hairy cell leukemia after treatment with cladribine. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:891–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Estey EH, Kurzrock R, Kantarjian HM, O'Brien SM, McCredie KB, Beran M, et al. Treatment of hairy cell leukemia with 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine (2-CdA) Blood. 1992;79:882–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juliusson G, Liliemark J. Rapid recovery from cytopenia in hairy cell leukemia after treatment with 2-chloro- 2'-deoxyadenosine (CdA): Relation to opportunistic infections. Blood. 1992;79:888–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seymour JF, Kurzrock R, Freireich EJ, Estey EH. 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine induces durable remissions and prolonged suppression of CD4+ lymphocyte counts in patients with hairy cell leukemia. Blood. 1994;83:2906–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zinzani PL, Tani M, Marchi E, Stefoni V, Alinari L, Musuraca G, et al. Long-term follow-up of front-line treatment of hairy cell leukemia with 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine. Haematologica. 2004;89:309–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tiacci E, Trifonov V, Schiavoni G, Holmes A, Kern W, Martelli MP, et al. BRAF mutations in hairy-cell leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2305–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samuel J, Macip S, Dyer MJ. Efficacy of vemurafenib in hairy-cell leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:286–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1310849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dietrich S, Hüllein J, Hundemer M, Lehners N, Jethwa A, Capper D, et al. Continued response off treatment after BRAF inhibition in refractory hairy cell leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:e300–3. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.9495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]