Abstract

Background:

One of the most critical stages of women's lives is menopause and one of the aims of health for all in the 21st century is the improvement of the quality of life.

Aim and Objective:

The aim of this study was to determine the effect of exercise on quality of life in postmenopausal women.

Materials and Methods:

This study was designed by a randomized-controlled trial. Eighty volunteer postmenopausal women who experienced the menopause period naturally and have been taking hormone replacement treatment (HRT) were divided into two groups randomly (exercise group n = 40, control group n = 40). The Nottingham Health Profile (NHP) was used to assess quality of life in both groups before and after 8 weeks. The exercise group participated in an exercise program, which was composed of sub-maximal aerobic exercises for an 8-week period 5 times a week. Quality of life in two groups was compared at the end of 8 weeks.

Results:

The results showed that there was a statistically significant difference in the exercise group for the NHP indicating an improvement in the quality of life (P < 0.05).

Conclusion:

We concluded that quality of life on postmenopausal women could be improved with a regular and controlled exercise program of 8 weeks. Thus, implementing appropriate educational programs to promote the quality of life in postmenopausal women is recommended.

Keywords: Exercise, menopause, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Women are among the most important foundations of the family and society; and the health of the community depends to a large extent, on meeting the needs of this group. One of the most critical stages of women's lives is menopause.[1] Menopause is the cessation of menstruation resulting from loss of ovarian follicular function, which is a recognized physiological event in women's lives. In addition to hormonal changes particularly reduction of estrogen levels with biological, psychological and social changes,[2] a woman who has not experienced menstrual period within at least 12 months retrospectively is deemed to have entered the phase of menopause and the postmenopausal period starts from this moment.[3,4,5]

Depending on the disorder of ovarian function and therefore, lack of estrogen in the postmenopausal period, symptoms such as hot flashes, irritability, sleeping disorders, fatigue, anxiety and loss of concentration are observed in the early period. Risk of coronary artery disease and incidence rate of osteoporosis increase due to loss of protective effects of estrogen in the later period. These symptoms in the postmenopausal period affect the quality of life of women adversely. If we assume menopause age as beginning at 50, women spend one-third of their lives with the pathological changes they are exposed to in the postmenopausal period.[3,4,5,6,7]

Earlier, the World Health Organization had reported that by 2003 there would be 1.2 billion women at and over age of 50. Therefore, although the menopause seems like a natural process, it is a period that must definitely be followed and treated.[7,8,9] One of the aims of health for all in the 21st century is the improvement of the quality of life.[1]

As a physiological event, menopause has complications that influence women's quality of life. Several measures such as hormone therapy and non-pharmacological therapies are recommended to reduce menopausal symptoms and improve quality of life in this period.[10]

Hormonal replacement treatment (HRT) is used as a standard therapy in menopausal treatment. The effect of exercise in preventing the postmenopausal symptoms as another aspect of treatment is widely accepted today. Postmenopausal symptoms can be prevented significantly by encouraging the women over middle age to gain the habit of exercising regularly.[8,9]

Prior research has showed that postmenopausal women living in cities are more sedentary. Due to unbalanced and single type nourishment, weight gain is a common phenomenon in those living in rural areas. The weight increase, which depends on age, inactivity and hormone drugs used in menopause, is minimized by regular exercise and the burning of excess calories.[11,12,13]

In the literature, there are studies that research the effects of exercise on muscle strength, bone density and on the postmenopausal symptoms in the women in postmenopausal period.[14,15] In addition, the studies in which the effects of exercises on quality of life is researched, is insufficient.[16]

In accordance, the objective of our study was to conduct an exercise program of 6 weeks and determine the changes on physical fitness levels and quality of life on postmenopausal women.

Our study is aimed to determine the effects of exercise on quality of life with a controlled exercise program of 8 weeks appropriate to the postmenopausal period.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study included 80 volunteers in the postmenopausal period who received HRT.

The inclusion criteria of this study were:

To have entered into the menopause naturally (subjects stated that they had no operation during their lives)

aged 45-65 old, to have been taking HRT for at least 1 year (subjects received combined continuous 0.62 mg per day conjugated estrogen (CE) + 2.5 mg per day medroxy-progesterone acetate (MAP)

To have no health problems that may prevent from doing exercise and to have no high cardiac risk

Exclusion criteria of this study were:

Postmenopausal women who exercise its check list was incomplete.

This study was approved by Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences.

Information about this study was provided to the subjects. Before being accepted into the study, each subject signed an informed consent form and obtained written permission from their physician. The researcher introduced the questionnaire to subjects and explained the material cover. It was explained to them that, if they preferred not to continue, they could withdraw from the study any time. After these explanations, the researchers gave the women the questionnaire.

Design

This was a randomized experimental trial with a control group. Postmenopausal women were randomly allocated by means of a random number table to one of two groups. Forty women in the first group were included into the 8-week aerobic exercise program and 40 women in the second group formed the non-exercise control group. The women in second group continued to take HRT and were not included in any exercise program.

Demographic characteristics were recorded. Quality of life was evaluated after 8 weeks in both groups.

Quality of life was evaluated by using the Nottingham Health profile (NPH). The NPH consisted of 38 yes/no items about health systems. Six different sub-sections of NPH included different numbers of questions with different scoring (physical mobility,[8] pain,[8] sleep,[5] energy,[3] social isolation[5] and emotional reactions[9]). Each sub-section's maximum cumulative score total should be 100 (worst health) and minimum 0 (best health). There was no summary score.[17]

The subjects were included in the exercise program for 8-week period with the frequency of 5 times a week. The program started with warming-up exercises consisting of stretching exercises and the 5-min low-intensity walking; warming-up exercises were followed by a program starting with 20 min and increasing up to 40 min at the end of 8 weeks. This program included the exercise detailed below: Bicycle for lower extremity endurance training for 5 to 15 min; exercise on the step board for lower extremity endurance for 2 to 6 min; posture exercises across a mirror for neck and back muscles (10 times); strengthening exercises with isoflex bands; free weights for back and abdominal muscles, pectoral, scapular muscles, and for upper-lower extremity muscles; balance exercise with trampoline for balance training; and flexibility exercise for pectoral, hamstring, gastro-cnemius-soleus, and back muscles.

The exercise program was completed with cooling exercises consisting of 5-min low-intensity walk on the treadmill. The exercise program with sub-maximal intensity was applied to the cases and a Borg scale was used in determining the intensity of the exercise. Exercise intensity was regulated by progressively increasing the repeating number, duration and endurance amounts of the exercises with the Borg scale follow-up.[18]

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 14.0. All data were reported as means ± standard deviation (SD). A paired sample t-test was used to compare the differences between before and after exercise at the same group and an independent sample t-test was used to compare the differences between the exercise and the control groups. ANOVA test was used for more than 2 groups and Chi-Square test respectively for continuous and categorical data. For all analyses, P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significance.

RESULTS

When these two groups were evaluated according to their physical characteristics, it was observed that they were homogeneous.

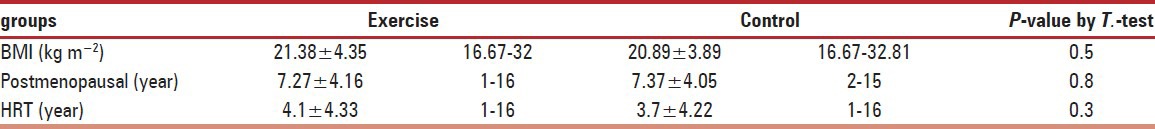

As shown in Table 1, the average age of the subjects was 54.05 ± 4.78 years with a range of 46-61. Furthermore, the number of years that they were menopausal, and the number of years that they were under HRT therapy was questioned as menopausal information and the answers were recorded. It was observed that these two groups were similar also in terms of menopausal characteristics.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic characteristics of subject

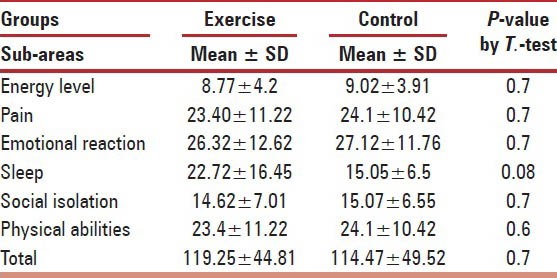

As shown in Table 2, there was no statistically significant difference according to NHP indicating an improvement in the quality of life before exercise.

Table 2.

Mean quality of life scores in the exercise and control groups before exercise

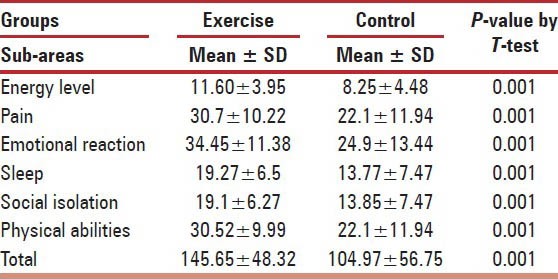

Results from the survey [see Table 3] in the exercise group show significant decreases in the scales of all the items indicating that the quality of life had been improved according to six sub-items of the NHP. No significant changes were found in the quality of life in the control group at the end of 8 weeks. At the end of the 8 weeks, there was a statistically significant difference in the exercise group according to NHP indicating an improvement in the quality of life.

Table 3.

Mean quality of life scores in the exercise and control groups after exercise

DISCUSSIONS

Menopause is a natural process that is seen in an average age of 50, and women spend almost one-third of their lives in the postmenopausal period. The quality of life worsens in the postmenopausal period as a result of the physical, psychological and social problems that start with menopause. It is emphasized in many studies that in order to achieve the best results from HRT, this therapy should be combined with an exercise program.[19] There are many studies indicating the negative effects of postmenopausal symptoms on quality of life. Luis Cobero, the President of Spain Gynecology and Obstetrics Association, had explained that the life qualities of postmenopausal women improve not only with HRT, but also with modifications in their diets, modifications in lifestyles, and regular physical activity.[20]

Güzeloglu applied NHP in order to establish the effects of osteoporosis in 50 postmenopausal women and reported that quality of life impairment increased with the duration of postmenopausal period. Güzeloglu emphasized that the reliability of NHP scale was rather high, and it could be used to evaluate the life quality of postmenopausal women.[21]

One intervention study concluded that fitness level and quality of life of postmenopausal women could be improved by a regular controlled exercise program of six weeks.[19]

Elavsky found that physical activity and menopausal symptoms were related to physical self-worth and positive effect, and in turn, greater levels of physical self-worth and positive effect were associated with higher levels of menopause-related quality of life.[16]

We also used NHP to evaluate the quality of life. It was found that life quality improved for all the sub-items of NHP in exercise group.

CONCLUSION

We concluded that quality of life could be improved with regular and controlled exercise of 8 weeks in postmenopausal women. When it is considered that our cases were not geriatric, our study has the properties of a protective treatment for these cases. The long-term effects of exercise on quality of life of our cases can be evaluated provided that the habit of exercising can be achieved by these individuals as a lifestyle. Studies that contain the data from this same group in subsequent years will be necessary for such an evaluation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge financial support for this study by Iran University of Medical Sciences & Health Services. We are grateful to all the research units and individuals participating in this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, et al. Writing Group for the Women's Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: Principal results from the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zapantis G, Santoro N. The menopausal transition: Characteristics and management. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;17:33–52. doi: 10.1016/s1521-690x(02)00081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vandenakker CB, Glass DD. Menopause and aging with disability. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2001;12:133–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siegel HR. Primary prevention of post menopausal osteoporosis. J Am Med Assoc. 1998;280:1821–2. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Croarkin E. Osteopenia implications for physical therapists managing patients of all ages, APTA. Continuing ed. 2001 Series No. 21. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Messinger-Rapport BJ, Thacker HL. Prevention for the older women: A practical guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis-continuing series. (21-4).Geriatrics. 2002;57:16–8. 27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doran AT. Book extra: Menopause and osteoporosis. People's Med Soc Newslett. 1998;17:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Browngoehl LA. Osteoporosis. In: Giasois M, Garrison J, Hart AK, Lehmkuh IDL, editors. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Ch. 85. Houston: Baylor College of Medicine; 2000. pp. 1564–75. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shangold MM, Sherman C. Exercise and menopause. Phys Sportsmed. 1998;26:45–50. doi: 10.3810/psm.1998.12.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shariat PS, Hajikazemi E, Nikpour S, Fghanipour S, Agha HF. Effect of yoga exercises on quality of life of postmenopausal women. Health Med. 2013;7:1266–73. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marcus R. Role of exercise in preventing and treating osteoporosis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2001;27:131–41. doi: 10.1016/s0889-857x(05)70190-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snow CM, Shaw JM, Winters KM, Witzke KA. Long-term exercise using weighted vests prevents hip bone loss in postmenopausal women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M489–91. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.9.m489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nied RJ, Franklin B. Promoting and prescribing exercise for the elderly. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65:419–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ager JC, Pierce LE, Raab DM, Mcadams M, Smith EL. Light resistance and stretching exercise in elderly women: Effect upon strength. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1988;69:273–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharkey NA, Williams NI, Guerin JB. The role of exercise in the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis and osteoarthritis. Nurs Clin North Am. 2000;35:209–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elavsky S. Physical activity, menopause, and quality of life: The role of affect and self-worth across time. Menopause. 2009;16:265–71. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31818c0284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson ME, Meyer RA. Health — related quality of life outcomes measures. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;8:30–44. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2000.20621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frolicher VF, Myers J, Foll WP, Labovitz AJ. 3rd ed. st. louis: Mosby-year book. Inc; 1993. Exercise and the heart; pp. 10–31. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teoman N, Ozcan A, Acar B. The effect of exercise on physical fitness and quality of life in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2004;47:71–7. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(03)00241-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bosch X. Spain focuses on quality of life during menopause. Lancet. 2000;355:478. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Güzeloglu SA. Thesis of Medical Sciences. Istanbul: 1999. Quality of life on postmenopausal women with Nottingham Health Profile. [Google Scholar]