Abstract

Background:

Perimenopausal period is characterized by a continuous decline in ovarian function due to which women are vulnerable to various physical and psychological symptoms affecting their quality of life. Currently these symptoms are managed by hormone replacement therapy. However, hormonal therapy can cause complications including malignancy which has resulted in search for various alternative therapies to improve the quality of life (QOL). Yoga is one such alternative therapy shown to enhance the QOL at all stages of human life associated with the chronic illness. There are very few scientific studies regarding the effect of yoga on perimenopause and in this study we investigated the effects of yoga therapy on physical and psychological symptoms using the standardized questionnaire.

Objective:

To study the effect of yoga therapy on physical, psychological, vasomotor and sexual symptoms of perimenopause.

Materials and Methods:

It is a prospective non-randomized control study of 216 perimenopausal women with 12 weeks of intervention. The subjects were divided in two groups with either yoga therapy [n = 111] or exercise [n = 105] as the interventional tool. The symptoms control and QOL before and after intervention in both the groups were assessed by using the menopausal QOL questionnaire.

Results:

The perimenopausal symptoms in all the four domains were improved by yoga therapy, thus significantly improving the overall QOL compared to the control group.

Conclusion:

This study clearly demonstrates the effectiveness of yoga therapy in managing the distressing perimenopausal symptoms. It is easy, safe, non-expensive alternative therapy helping the well-being of perimenopausal women and must be encouraged in the regular management of perimenopausal symptoms.

Keywords: MENQOL questionnaire, perimenopausal QOL, yoga therapy

INTRODUCTION

Menopause is an important event in the life of a woman when reproductive capacity ceases. During this transitional phase, woman exhibits severe and multiple symptoms. Frequently reported symptoms fall into several categories, including physical disturbances such as hot flushes, psychological complaints such as mood swings, and other changes that may impair personal or social interactions and diminish the overall quality of life.[1] In 1990, there were an estimated 467 million women in this state and this number is expected to increase to 1,200 million by the year 2030.[2] According to the Indian Menopause Society,[3] there will be a large increase in the perimenopausal women in India also. Most women in India over the age of 45 years do not understand the changes taking place in their bodies and spend their valuable years of life battling problems and diseases associated with perimenopause. Hence it becomes very important to develop methods and treatment plans to control perimenopausal symptoms and thereby to improve the quality of life of this large group of women.

To improve the immediate symptoms of menopause and to manage its long-term consequences, hormonal therapies have been used extensively. However, these therapies have created new concerns about the increased risk of neoplasia of the endometrium and possibly the breast[4,5,6] and hence several researchers have investigated the role of alternative therapies in the management of menopausal symptoms and quality of life.

Yoga, the traditional Indian body-mind science has been used effectively in various health disorders affecting almost all the major organ system including cardiovascular, respiratory, neuroendocrine, gastrointestinal and musculoskeletal system.[7,8,9] Since perimenopause also affects several organ systems, we conducted this study to evaluate the effects of yoga therapy on menopausal symptoms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This interventional study included 216 perimenopausal women divided into two groups. One group practiced yoga therapy (test group, n = 111) and the other practiced a set of physical exercise (control group, n = 105). All these subjects satisfied the inclusion criteria of:

Aged between 40-60 years,

Who were willing and were able to practice yoga or exercise protocols and,

Who were having perimenopausal symptoms and were included in this study.

Exclusion criteria were:

Women who were already practicing yoga for a month or more,

Women with surgical menopause and receiving any kind of hormone therapy and

Active psychological disorders or any other medical disorders.

The subjects were from local community and recruited through personal contacts with various women's organizations, clubs (Lion's/Rotary) and self-help groups. Ethical clearance was obtained from the institutional review board (IEC 062/2008) and the informed consent was obtained from the subjects before starting the intervention.

Yoga and exercise intervention

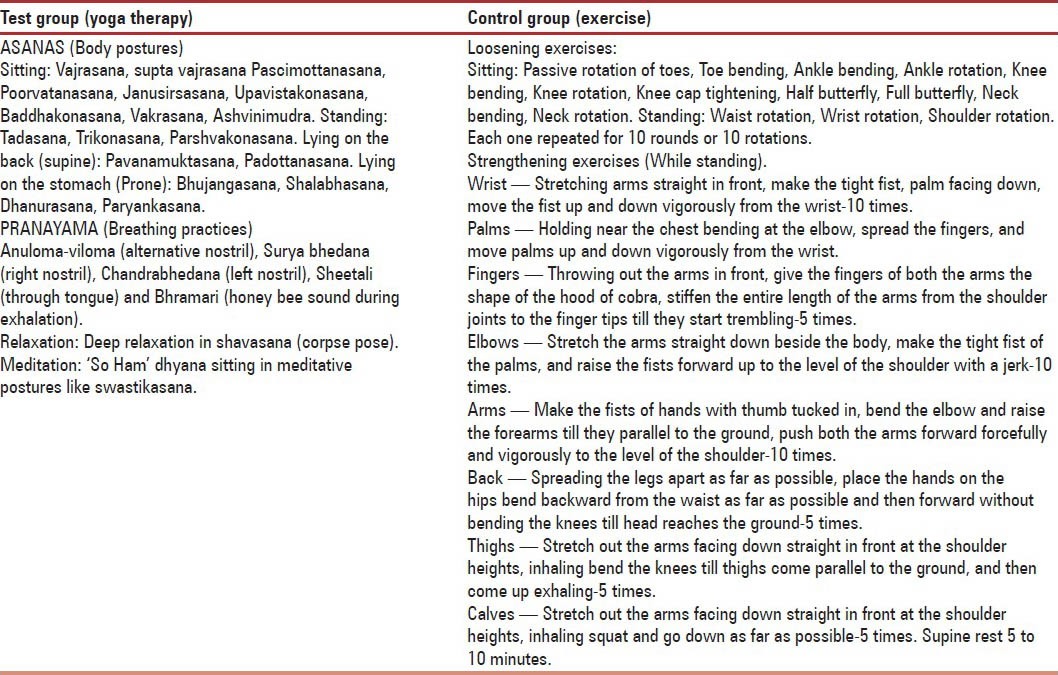

The yoga therapy module used was developed on the basis of Patanjala yoga[10] and Hatha yoga[11] to address the physical, psychological and emotional symptoms with suitable practice of asanas, pranayamas and dhyana to result in improvement of overall quality of life. The control group practiced a set of exercise program.[12] [Table 1] Both the practices were initially taught under the direct contact of the principal investigator for first two weeks and were later continued with the help of suitable hand outs and regular supervision and follow-up.

Table 1.

Practices used for the two interventional groups

The intervention program in both groups were started by collecting the baseline data, teaching and practicing the respective protocols for 45 minutes every day, follow-ups and collection of post-interventional data after 12 weeks of practice.

Menopause-specific quality of life questionnaire (MENQOL)

The self-administered questionnaire utilized in this study included socio-demographic information with menstrual history and the menopause-specific quality of life questionnaire (MENQOL).[13] MENQOL is a self-administered, ‘scaled’ 29-item survey questionnaire, designed to measure quality of life in menopausal women and also to measure the extent to which an individual is affected by menopausal symptoms. It comprises the four domains, Vasomotor, Psychosocial, Physical and Sexual, which are graded separately.

Statistical analysis

All pre and post data were analyzed by using SPSS Version 15. The individual variables were evaluated to determine the changes in two groups after 12 weeks. The pre and post data of MENQOL questionnaire total and domain wise was analyzed by using repeated measures of ANOVA. The effectiveness was calculated as ‘within the group’ (yoga and control group), ‘between the groups’ (yoga vs. control) and ‘Effect size’ (mean difference) to deduce the superiority of the methods involved and results are reported as mean ± SD.

RESULTS

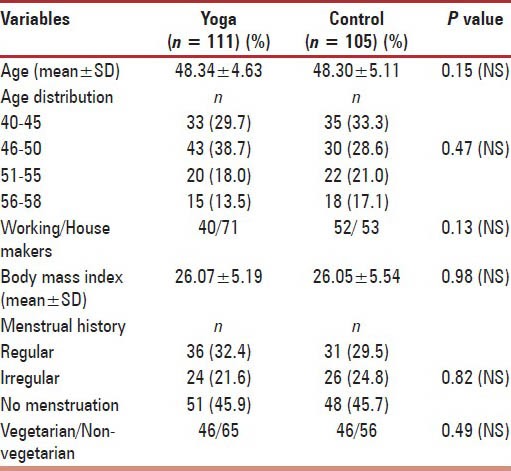

The socio-demographic data are shown in Table 2. The mean age of the women in yoga group was 48.34 ± 4.63 and in control group was 48.30 ± 5.11. Age was statistically comparable between the groups with P = 0.15. The largest categories of women were between 46 and 55 years of age. No significant difference was observed between the groups regarding body mass index and menstrual history.

Table 2.

Socio-demographic data

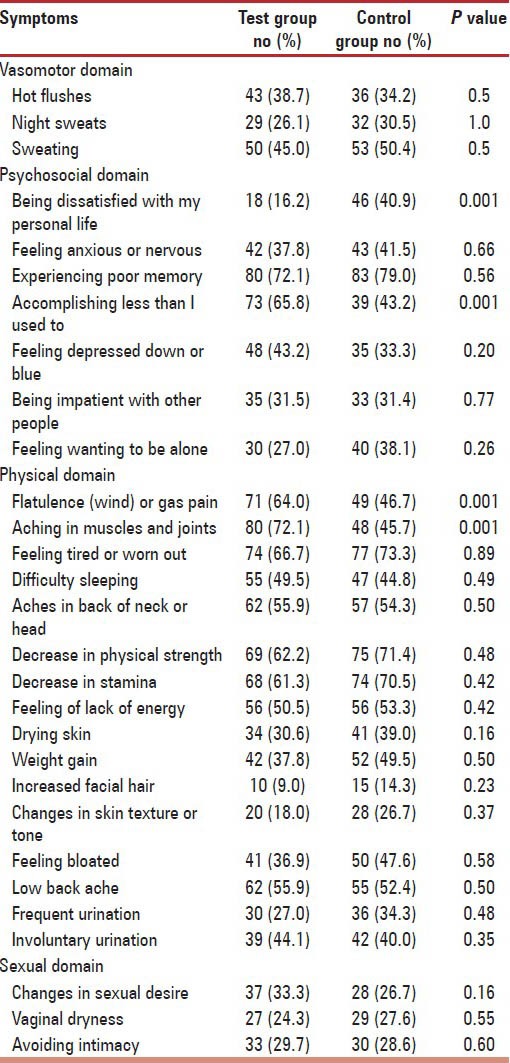

The prevalence of vasomotor, psychosocial, physical and sexual domain symptoms and baseline comparison between the groups is shown in Table 3. In the vasomotor domain sweating was the most predominant disturbing symptom complained by women in both the groups followed by hot flushes and night sweats. There was no significant difference between the groups (P > 0.05). In the psychosocial domain, large number of women from both the groups (72% to 79%) complained experiencing poor memory as the most prevalent symptom followed by feeling of anxiety, loneliness, depression and impatience. Two of the questions in this domain that is being dissatisfied with personal life and accomplishing less what I used to do were recorded more significantly by control group compared to the yoga group (P < 0.001) while other attributes from this domain were all comparable (P > 0.05). All the symptoms in the physical domain except for flatulence and muscles and joint pains were comparable in both groups without any significant difference. No significant difference was observed in the response to sexual domain between the two groups (P > 0.05).

Table 3.

The baseline comparison of perimenopausal symptoms in each domain of MENQOL between test and control group

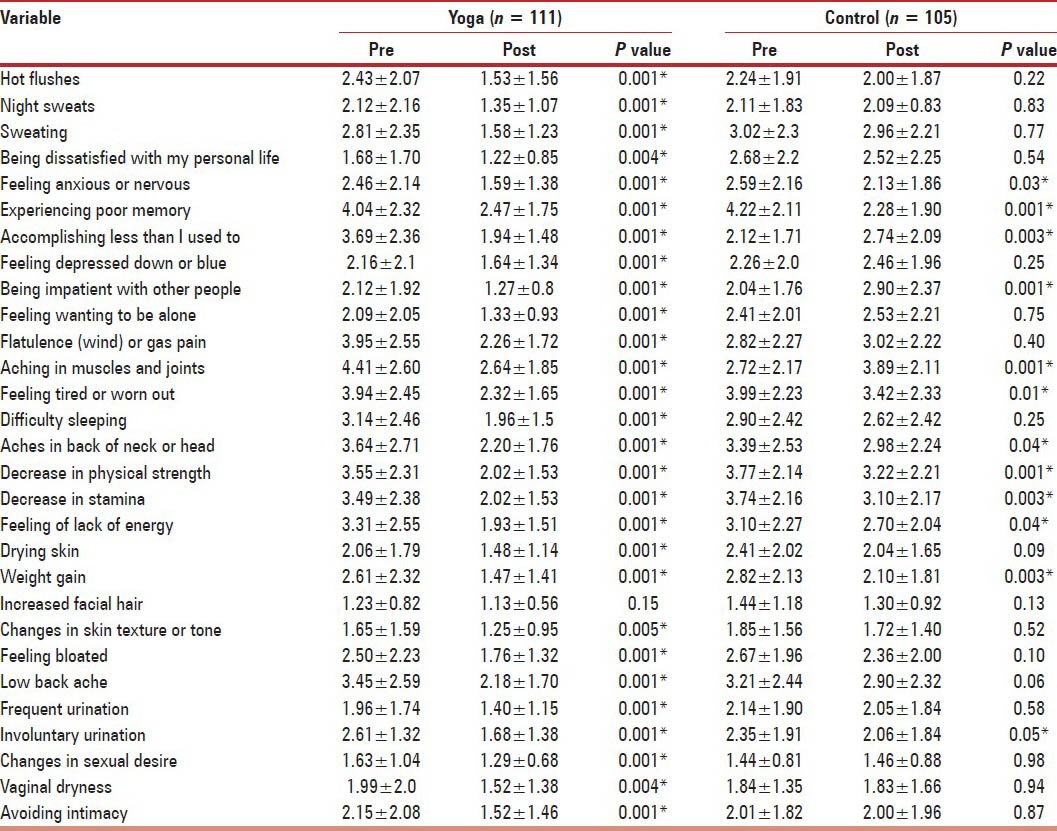

The results of effect of yoga therapy (test group) and exercise (control group) on the symptoms of all the four domains are presented in Table 4. The pre and post mean ± SD result of vasomotor domain symptoms showed significant decrease in yoga group compared to exercise group. In the psychosocial domain, yoga therapy resulted in the significant difference in all the symptoms while exercise therapy resulted in the improvement of four symptoms but failed to provide relief for the remaining three symptoms. All the symptoms in the physical domain were significantly improved in yoga group, except for increased facial hair. In control group, highly significant (P < 0.001) decrease was observed only in one symptom and moderate in other six symptoms. The symptom of aching in muscles and joints was aggravated after physical exercise and no significant change was observed in the remaining eight symptoms. Yoga therapy also resulted in significant improvement in all the symptoms of sexual domain while physical exercise showed no significant improvement.

Table 4.

The pre and post mean values of MENQOL in both the groups

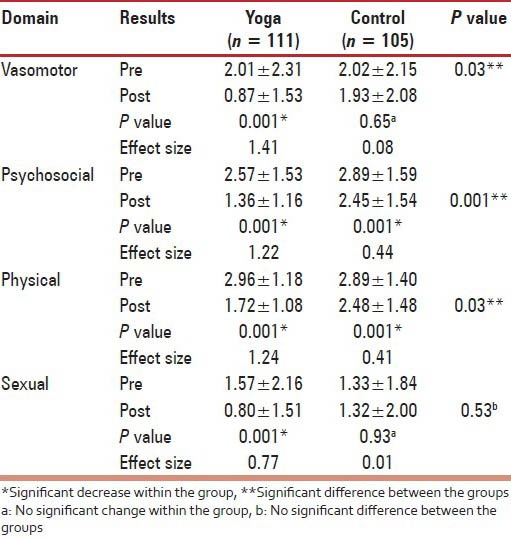

This study brought out the subtle differences between the efficiency of the two interventions (yoga and exercise) to evaluate the effectiveness, and it has been showed in the form of effect size. The quality of life is the mean of the overall score of each domain. While analyzing the result ‘within the group effect’ yoga therapy showed a significant decrease (P < 0.001) in the mean scores of all the domains, whereas control group showed a significant decrease (P < 0.001) only in psychosocial and physical domains. The ‘effect size’ was greater in yoga therapy group in all domains compared to the control group. ‘Between the group effect’, there was significant difference between the groups in all domain except for sexual domain (P = 0.53) [Table 5].

Table 5.

The QOL of each domain in both the groups

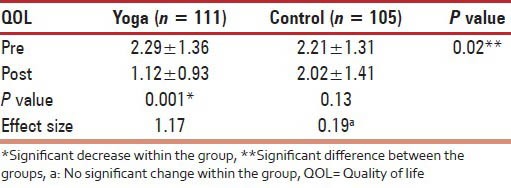

The overall quality of life is measured by the mean of overall scores of the each domain and yoga therapy group showed a very significant improvement (P < 0.001) compared to control group [Table 6].

Table 6.

Overall quality of life (Total)

DISCUSSION

The present study thus clearly documents the significant presence of various perimenopausal symptoms in the local population severely affecting the quality of life. Many of these women expressed their distress and helplessness regarding these symptoms, which were seriously interfering in their day-to-day living. Thus there is a need to search and develop a cost-effective, simple, community-based therapeutic tool to provide symptom relief and to improve health status, and in this perspective yoga has emerged as the appropriate system to deal effectively with issues related to perimenopause. The present study clearly demonstrates the clinical utility of yoga in significantly reducing the perimenopausal symptom in all domains and thereby improves the overall quality of life.

Asanas, pranayama and dhyana, the components of yoga therapy, seem to improve the symptom profile in the four domains through several physiological and biochemical mechanisms. The improvement in physical strength and fitness caused by yoga seems to be related to several factors like muscular strength and endurance, flexibility, cardiorespiratory fitness, body composition and pulmonary function.[14] The intense stretching and muscle conditioning associated with attaining and holding yoga postures increases the skeletal muscle oxidative capacity and decrease glycogen utilization, possibly caused by increased vascularization, increased intramuscular oxygen and glycogen stores or by increased numbers of mitochondria.[15] Yoga practice also may increase the absorption of the calcium from the intestine, stimulate bone remodeling and maintain the load bearing capacity of the bone; reduces the pain in the back of the head, neck, lower back and headache by influencing limbic system modulation of endogenous pain control system.[16]

Ours is the first study to document the beneficial effects of yoga on perimenopausal-related psychological symptoms. This impact of yoga seems to be due to its effect on the functioning of nervous system leading to increase in alpha rhythm, intrahemispheric coherence and homogeneity in the brain[17,18] and increase in P 300 phase amplitude[19] all of which seems to enhance the cognitive processes. Menopausal anxiety can be a very difficult symptom to manage, but yoga therapy showed significant improvement compared to physical exercise. Several mechanisms like altered neurotransmitters,[20] changed brain blood flow and brain metabolism[21] and sympathetic activation[22] seems to be responsible for this improvement brought by yoga practice.

Compared to physical exercise group, yoga showed most significant effect in managing the symptoms of vasomotor domain. All the three symptoms in this domain, that is, hot flushes, night sweats and sweating were significantly reduced in the yoga group while no improvement was observed in any of the symptoms in control group. Especially, the improvement in hot flushes through yoga was very rewarding, since this is most difficult symptom to manage and affects the overall quality of life. The vasomotor symptom improvement brought about by yoga intervention seems to be due to its effect in modulating autonomous nervous system with special attention to decreased sympathetic nervous system activation[23,24] which in turn seems to affect the thermoregulation resulting in vasodilatation and sweating.[25]

All the three symptoms in the sexual domain were also significantly improved after yoga therapy. Though the reported prevalence of sexual complaints in Asian woman is lower than in their Caucasian counterparts, improvements in these symptoms contribute to the overall quality of life. The yoga postures used in this study are known to improve the tone of the muscles of pelvic region and enhance the blood circulation to the urogenital area.[26]

Thus, yoga improved most of the symptom profile thus contributing significantly in the improvement of overall quality of life. Yoga is relatively simple to learn and is economical, non-invasive with multiple collateral lifestyle benefits. Group and individual practice may also help to improve lifestyle choices and health-related attitudes in part, by enhancing psychological well-being and thereby contributing significantly to chronic disease protection and health promotion. Though most of the clinical effects of yoga are probably brought about by vagal stimulation and parasympathetic activation, the complete mechanisms underlying the reported benefits remain poorly understood. Clearly, additional high-quality research is warranted to confirm and further explore the putative beneficial effects of yoga in perimenopausal women.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Speroff L. The menopause a signal for the future. In: Lobo RA, editor. Treatment of the Postmenopausal Women. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 1999. pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Research on menopause in the 1990s. Report of a WHO Scientific Group. World Health Organization. 1996 WHO Technical Report Series No. 866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meeta, Digumurti L, Agarwal N, Vaze N, Shah R, Malik S. Clinical practice guidelines on menopause: An executive summary and recommendations. J Midlife Health. 2013;4:77–106. doi: 10.4103/0976-7800.115290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hulley S, Grady D, Bush T, Furgerg C, Harrington D, Riggs B, et al. Randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in post-menopausal women. Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS) Research Group. JAMA. 1998;280:605–13. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.7.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, et al. Writing Group for Woman's Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal woman: Principal results From the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beral V. Million Women Study Collaborators. Breast cancer and hormone-replacement therapy in the Million Women Study. Lancet. 2003;362:419–27. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sengupta P. Health impacts of yoga and pranayama: A State-of-the Art Review. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3:444–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woodyard C. Exploring the therapeutic effects of yoga and its ability to increase quality of life. Int J Yoga. 2011;4:49–54. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.85485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCaffrey R, Park J. The benefit of yoga for musculoskeletal disorders: A systematic review of the literature. J Yoga Phy Ther. 2012;2:122. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adidevananda S. 1st ed. Mysore: Sri Ramakrishna Ashrama; 1981. Patanjala-yoga darshana; pp. 112–341. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brahmananda . 2nd ed. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House; 1933. The Hatayoga Pradeepika of Svatmarama; pp. 22–37. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagarathna R, Nagendra HR. 1st ed. Bengaluru: Sharada Enterprises; 2001. Yoga for Arthritis; pp. 35–511. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hilditch JR, Lewis J, Peter A, van Maris B, Ross A, Franssen E, et al. A menopause-specific quality of life questionnaire: Development and psychometric properties. Maturitas. 1996;24:161–75. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(96)82006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tran MD, Holly RG, Lashbrook J, Amsterdam EA. Effects of hatha yoga practice on the health-related aspects of physical fitness. Prev Cardiol. 2001;4:165–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1520-037x.2001.00542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shephard RJ, Astrand PO, editors. Vol. 2. London: Black wall Science Ltd; 2008. Endurance in sports. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhatia R, Dureja GP, Tripathi M, Bhattacharjee M, Bijalani RL, Mathur R. Role of temporalis muscle over activity in chronic tension type headache: Effect of yoga based management. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2007;51:333–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khare KC, Nigam SK. A study of electroencephalogram in meditators. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2000;44:173–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma VK, Das S, Mondal S, Goswamy U, Gandhi A. Comparative effect of sahaj yoga on EEG in patients of major depression and healthy subjects. Biomedicine. 2007;27:95–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sarang SP, Telles S. Changes in p300 following two yoga based relaxation techniques. Int J Neurosci. 2006;116:1419–30. doi: 10.1080/00207450500514193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Streeter CC, Jensen EJ, Perlmulter RM, Cabral HJ, Tian H, Terhune DB, et al. Yoga asana session increase brain GABA level: A pilot study. J Alter Complement Med. 2007;13:419–26. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.6338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lou HC, Kjaer TW, Friberg L, Wildschiodtz G, Holm S, Nowak M. A 150-H20 PET study of meditation and the resting state of normal consciousness. Hum Brain Mapp. 1999;7:98–105. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1999)7:2<98::AID-HBM3>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kjaer TW, Bertelsen C, Piccini P, Brooks D, Alving J, Lou HC. Increased dopamine tone during meditation-induced change of consciousness. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 2002;13:255–9. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(01)00106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vempathi RP, Telles S. Yoga-based guided relaxation reduces sympathetic activity judged from baseline levels. Psychol Rep. 2002;90:487–94. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2002.90.2.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dvivedi J, Kaur H, Dvivedi S. Effect of one week ‘61-point relaxation training’ on cold pressor test induced stress in premenstrual syndrome. Indian J Physiol Pharmocol. 2008;52:262–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freedman RR, Kreg W. Reduced thermoregulatory null zone in postmenopausal women with hot flushes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:66–70. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70437-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deshikachar TV. Nathamuni's yoga rahasya. In: Krishnamacarya T, editor. 1st ed. Chennai (India): Krisnamacarya yoga mandiram; 1998. [Google Scholar]