Abstract

Background

Human xylosyltransferase-I (XT-I) catalyzes the rate-limiting step in proteoglycan glycosylation. An increase in XYLT1 mRNA expression and serum XT activity is associated with diseases characterized by abnormal extracellular matrix accumulation like, for instance, fibrosis. Nevertheless, physiological and pathological mechanisms of transcriptional XT regulation remain elusive.

Results

To elucidate whether promoter variations might affect the naturally occurring variability in serum XT activity, a complete sequence analysis of the XYLT1 promoter was performed in genomic DNA of healthy blood donors. Based on promoter amplification by a specialized PCR technique, sequence analysis revealed a fragment of 238 bp, termed XYLT1238*, which has never been described in the human XYLT1 reference sequence so far. In silico characterization of this unconsidered fragment depicted an evolutionary conservation between sequences of Homo sapiens and Pan troglodytes (chimpanzee) or Mus musculus (mouse), respectively. Promoter activity studies indicated that XYLT1238* harbors various transcription factor binding sites affecting basal XYLT1 expression and inducibility by transforming growth factor-β1, the key fibrotic mediator.

A microsatellite and two single nucleotide variants (SNV), c.-403C>T and c.-1088C>A, were identified and genotyped in 100 healthy blood donors. Construct associated changes in XYLT1 promoter activity were detected for several sequence variants, whereas serum XT activity was only marginally affected.

Conclusions

Our findings describe for the first time the entire XYLT1 promoter sequence and provide new insights into transcriptional regulation of XT-I. Future studies should analyze the impact of regulatory XYLT1 promoter variations on XT-associated diseases.

Keywords: Xylosyltransferase, Promoter, Single-nucleotide variant, Microsatellite, Gene regulation

Background

The isoenzymes human xylosyltransferase-I and -II (XT-I/-II; EC 2.4.2.26) catalyze the key step of glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis by transferring activated UDP-xylose to selected serine residues on a proteoglycan core-protein in the golgi [1,2]. Proteoglycans are components of the extracellular matrix (ECM) responsible for tissue stabilization, hydration and efficient functionality of various signal transduction pathways [3,4].

In fibrosis, a dysbalance of matrix synthesis and degradation results in abnormal matrix accumulation, which initiates the functional loss of the affected organ. Although different origins of fibrotic tissue remodeling processes, as well as their molecular mechanisms are described, no anti-fibrotic treatment could be developed until now [5,6]. Among others, an increased XYLT1 mRNA expression, as well as XT secretion and serum activity could be shown to be associated with a rise in myofibroblast differentiation and matrix synthesis in liver fibrosis, skin fibrosis or dilated cardiomyopathy [7-10]. Recently, dysregulations of XT have also been connected with the manifestation of osteoarthritis or disorders of ossification [11-13].

XT-I and -II, encoded by the genes XYLT1 and XYLT2, are characterized by slight differences in their substrate specificities. Nevertheless, they are distinguishable by their local tissue expression patterns [14,15]. Based on the hypothesis that XT are pivotal regulators of pathobiochemistry, current studies address the analysis of their regulatory mechanisms. With regard to transcriptional control, two central key mediators, TGF-β1 and IL-1β, were identified [9,11]. Unfortunately, due to their wide-spread scope, none of these proteins represents an adequate point of therapeutic application. Thus, it is of great importance to identify additional basic pathways of XT regulation.

So far, XYLT1 and XYLT2 promoter regions have been initially identified and characterized. It could be demonstrated that both regions miss common eukaryotic promoter elements like a TATA- or CAAT-box, contain highly GC-rich passages upstream of the translational start site and are controlled by transcription factors of the AP- and SP-family [16,17]. Due to the highly GC-rich template, XYLT1 promoter characterization was based on gene synthesis referring to the XYLT1 reference sequence [GenBank Accession Number NG_015843.1]. Therefore, neither the XYLT1 promoter conservation nor the occurrence of its sequence variants was formerly defined.

The aim of this study was to analyze whether naturally occurring promoter sequence variants like single nucleotide variants (SNV) could play an emerging role in XYLT1 transcriptional regulation. A microsatellite and two SNV were identified and genotyped in genomic DNA of 100 healthy blood donors, although these variants exerted only marginal effects on serum XT activity. Nevertheless, the SNV c.-1088C>A significantly reduced promoter activity. In addition to SNV screening, we identified and characterized an evolutionary conserved fragment of 238 bp in the XYLT1 promoter region which has never been described in the published XYLT1 human reference sequence so far. In summary, this is the first study defining and characterizing the variability of the complete XYLT1 promoter sequence in the general population which in turn extensively enlarges our insights in promoter organization and transcriptional regulation of human XT-I.

Methods

Study subjects and collection of blood samples

For this study, EDTA plasma and serum samples of 100 healthy blood donors (50% males; 18-60 years of age; mean age +/- SD: 36.2 +/- 13.5 years) were collected. The experimental design and research has been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics committee (medical faculty, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Bad Oeynhausen, Germany). All blood donors gave their informed consent.

DNA extraction and XYLT1 promoter amplification

After plasma centrifugation, genomic DNA was extracted from 200 μL EDTA blood leukocytes using the Nucleo Spin Blood Kit (Macherey-Nagel). Referring to the current XYLT1 reference sequence [GenBank Accession Number NG_015843.1], the promoter region was divided into four overlapping fragments termed D (c.-1689 to c.-1273), C (c.-1385 to c.-813), B (c.-891 to c.-215) and A (c.-372 to c. + 122). The amplification of fragments D, C and B was performed by an initial denaturation step at 95°C (15 min) followed by 35 cycles (denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, annealing at optimal annealing temperature (TA) for 1 min and elongation at 72°C for 1 min) and final elongation at 72°C for 15 min. All PCR and sequencing reactions were run on thermocycler T professional (Biometra). Primer sequences and TA are listed in Table 1. The reaction mixture was composed of 11.15 μL water, 5.0 μL Q-Solution (Qiagen), 0.25 μL dNTPs (25 mM), 2.5 μL reaction buffer (Qiagen), 0.5 μL of each primer (25 μM), 5.0 μL template (dilution 1:5) and 0.1 μL HotStar Taq DNA-polymerase (Qiagen). The amplification of the GC-rich A fragment required highly specialized conditions. The used slowdown-PCR cycling conditions are described elsewhere, while the composition of the reaction mixture (15.8 μL water, 10.0 μL Q-Solution, 5.0 μL reaction buffer, 2.0 μL of each primer (2.5 μM), 1.0 μL of dATP, dTTP and dCTP (10 mM), 2.5 μL of dGTP (1 mM), 7.5 μL dc7GTP (1 mM; Roche), 0.2 μL HotStar Taq DNA-polymerase and 2.0 μL template) was adjusted [18,19].

Table 1.

Primers used for amplification, sequencing and site-directed mutagenesis (SDM) of XYLT1 promoter fragments

| Application | Primer sequence ( 5′ → 3 ′) | T A [°C] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCR and sequencing | Fragment A | CCCTGTTTCGCGGCCCCTG | Slowdown-PCR |

| CCGGAGTCGAGGCTGCTGAA | |||

| Fragment B1 | ATGGATGGGGAAAAGGACAC | 58.8 | |

| TGGGGGAGGAGCCGAGGGAG | |||

| Fragment B2 | CAGTCAGGATGGGAAAGAAC | 58.8 | |

| GGTGCCAACGATGTACTAAG | |||

| Fragment C | AACAATCTCTTCCCACTCCC | 61.2 | |

| GGAGTTACTCAACCTTCGCA | |||

| Fragment D | CATGCCCGGCTAATTTTTGT | 61.2 | |

| CTTCGCATCTTGTCTGCTGT | |||

| Fragment XYLT1 238* | ACAGGGGTGTGGGGAGGGGGCGCCGCGCGGGCCAGGCGCC | 58.8 | |

| GCTCGGGCCGCCGCCGCCGCCGCCGCCTCGGCTCGCCGCT | |||

| Plasmid sequencing | CTAGCAAAATAGGCTGTCCC | ||

| CTTAATGTTTTTGGCATCTTCCA | |||

| SDM | c.-403C>T | TCCCCCCGGCGCCTTCCCCATTACCCTCCCCTCCAGCGGGGA | |

| TCCCCGCTGGAGGGGAGGGTAATGGGGAAGGCGCCGGGGGGA | |||

| c.-1088C>A | GCTGGGAGGCTGCGGGGCCAGACTTTGGGGCTTGCATCCTGC | ||

| GCAGGATGCAAGCCCCAAAGTCTGGCCCCGCAGCCTCCCAGC |

Mutated bases are marked in bold.

Promoter sequencing, mutational analysis and genotyping

Sanger sequencing was initiated by PCR product clean-up. 5.0 μL of the PCR product were incubated with 2.0 μL of exonuclease I (NEB), as well as 2.0 μL shrimp alkaline phosphatase (Affymetrix) at 37°C for 30 min and 80°C for 15 min. 2.0 μL of the reaction mixture were added to a sequencing master mix containing 5.5 μL water, 5.0 μL Q-solution (Qiagen), 4.0 μL BigDye v3.1 sequencing premix (Life technologies), 2.0 μL 5 × BigDye sequencing buffer (Life technologies) and 1.5 μL primer (25 μM; listed in Table 1). Sequencing reaction started with a denaturation step at 95°C for 2 min and run for 30 cycles (denaturation at 95°C for 10 s, annealing at TA for 10 s, elongation at 60°C for 4 min). After purification by a sephadex-G50 spin-column based protocol, sequences were analyzed by capillary electrophoresis using the Genetic Analyzer 3500 (Life technologies).

Promoter construct cloning and insertion of SNV by site-directed mutagenesis

Construction of pGL4.10 luciferase reporter vectors containing the XYLT1 promoter fragments c.-1639 to c.+1Δ238* or c.-1031 to c.+1Δ238*, according to the current uncomplete reference sequence, was described previously [16]. To adjust the promoter length, we inserted the missing region XYLT1238* using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent). XYLT1238* was amplified from the PCR product of the A fragment (primers are listed in Table 1) and purified by the MSB Spin PCRapace kit (Stratec). Site-directed mutagenesis cycling conditions and composition of the reaction mixture are published elsewhere [20]. To insert single nucleotide sequence variants in the synthesized vector construct c.-1031 to c.+1complete, site-directed mutagenesis was applied according to the manufacturer’s instructions (primers are listed in Table 1). Successful insertion of XYLT1 promoter fragment or single base exchange was checked by amplification and sequencing of the appropriate plasmid region or direct plasmid sequencing using vector specific primers (Table 1).

Cell culture and transient transfection of plasmids

SW1353 chondrosarcoma cells were routinely grown in RPMI 1640 medium (Life technologies), supplemented with 10% FCS (Pan biotech) and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic solution (PAA). For transfection, 180000 cells were seeded in triplicate in 6 well culture dishes and incubated for 24 h. The next day, 188 μL medium (without any supplements) were mixed with 12 μL FuGene 6 transfection reagent (Promega) and incubated at RT for 5 min. After addition of 1 μg of the appropriate pGL4.10 plasmid and 10 ng of pGL4.74, the reaction mixture was incubated for 30 min and applied to the cells. After 24 h, the cell culture medium was replaced. Where appropriate, TGF-β1 (7.5 ng/mL, Miltenyi Biotech) was added. Cells were harvested in 500 μL lysis buffer and promoter activity was analyzed after 48 h.

Dual luciferase reporter assay

Cellular luciferase activity was assayed with the Dual Luciferase Reporter assay system (Promega) on a Lumat LB9705 luminometer (EG&G). 20 μL lysate were incubated with 100 μL LARII substrate to stimulate substrate turnover of firefly luciferase (encoded by the pGL4.10 vector construct upstream of the XYLT1 promoter sequence). Addition of 100 μL Stop&Glo solution inhibited firefly luciferase and simultaneously induced substrate turnover of renilla luciferase (encoded by the co-transfected pGL4.74 vector). To calculate relative luciferase activity representing promoter activity, firefly luciferase activity was measured in each sample and normalized to renilla luciferase activity. Normalization reduced the impact of differences in efficiency of transfection or lysis.

XT activity assay

Determination of serum XT activity was performed as described before. The method relies on incorporation of 14[C] D-xylose (Du Pont) into silk fibroin receptor protein. Measured disintegrations per minute (dpm) are proportional to enzymatic activity [21,22].

In silico analysis

In silico analysis of transcription factor binding sites was carried out using the Genomatix online software suite, while sequence alignments were performed with Clone Manager 9.0 (Scientific & Educat. Software) and ClustalW (DNA Star Inc.). Evaluation of LD maps and haplotype frequencies was carried out using Haploview 4.0 (Broad Institute) [23]. Blocks were defined according to the “solid spine of LD” setting in the software.

Statistics

Experimental data were analyzed by Mann-Whitney-U-Test using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software). p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. To examine whether genotype distributions fit into the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, a χ2-test was performed.

Results

Sequence analysis of the human XYLT1 promoter region

To screen for natural occurring variants in the XYLT1 promoter, we performed a preliminary sequence analysis of the genomic DNA of ten healthy blood donors. Referring to the published XYLT1 reference sequence [GenBank Accession Number NG_015843.1], the amplification was performed by splitting the region into four fragments, A to D. Due to a high GC-content of 75%, the A fragment (c.-372 to c.+122), could exclusively be amplified by slowdown-PCR conditions. Sequencing results demonstrated that the XYLT1 promoter region does not comprise just 1639 bp, as published earlier [16] but also harbors an additional fragment of 238 bp in between the known sequence of the A fragment. The nucleotide sequence for the A fragment has been deposited in the GenBank database [GenBank Accession Number KM079589].

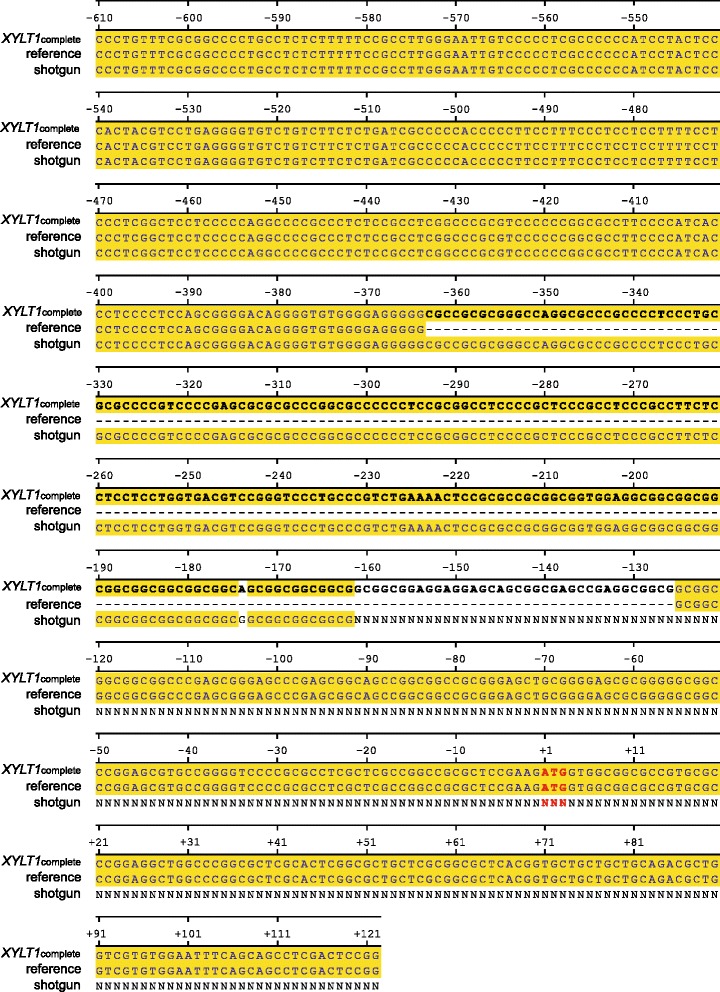

The identification of this hitherto undescribed XYLT1 promoter fragment, termed XYLT1238*, was verified by sequencing the genomic DNA of 100 healthy blood donors. All PCR products spanned approximately 700 bp, so none of the amplificates displayed the calculated fragment length of 494 bp, referring to the current XYLT1 reference sequence [GenBank Accession Number NG_015843.1]. A sequence alignment of the reference sequence, as well as the consensus sequence of the XYLT1 promoter sequence XYLT1complete, identified in this study, confirmed the absence of XYLT1238* in the published reference sequence (Figure 1). In the following, base numbering depends on promoter sequence XYLT1complete, whereby the first nucleotide of the translation initiation start site was defined as c.+1 and promoter nucleotides were numbered backwards. XYLT1238* was located at position c.-363 to c.-126. By screening data bases for complementary human DNA reference sequences, in silico analysis revealed the deposition of only one shotgun sequence [GenBank Accession Number NW_001838365.2] conforming to XYLT1238*. However, due to a sequence cut off at position c.-162, XYLT1238* is merely partially listed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sequence alignment of human genomic XYLT1 promoter sequences ( c .- 610 to c .+ 122 ). The sequence examined in this study (XYLT1 complete, [GenBank Accession Number KM079589]) was compared with the appropriate XYLT1 promoter region of the current human reference sequence [GenBank Accession Number NG_015843.1] and a human shotgun sequence [GenBank Accession Number NW_001838365.2]. Numbers indicate the nucleotide position up- or downstream of the translation initiation site ATG (red color). Matching nucleotides are shaded in yellow, whereas XYLT1 238* (c.-363 to c.-126) is marked in bold.

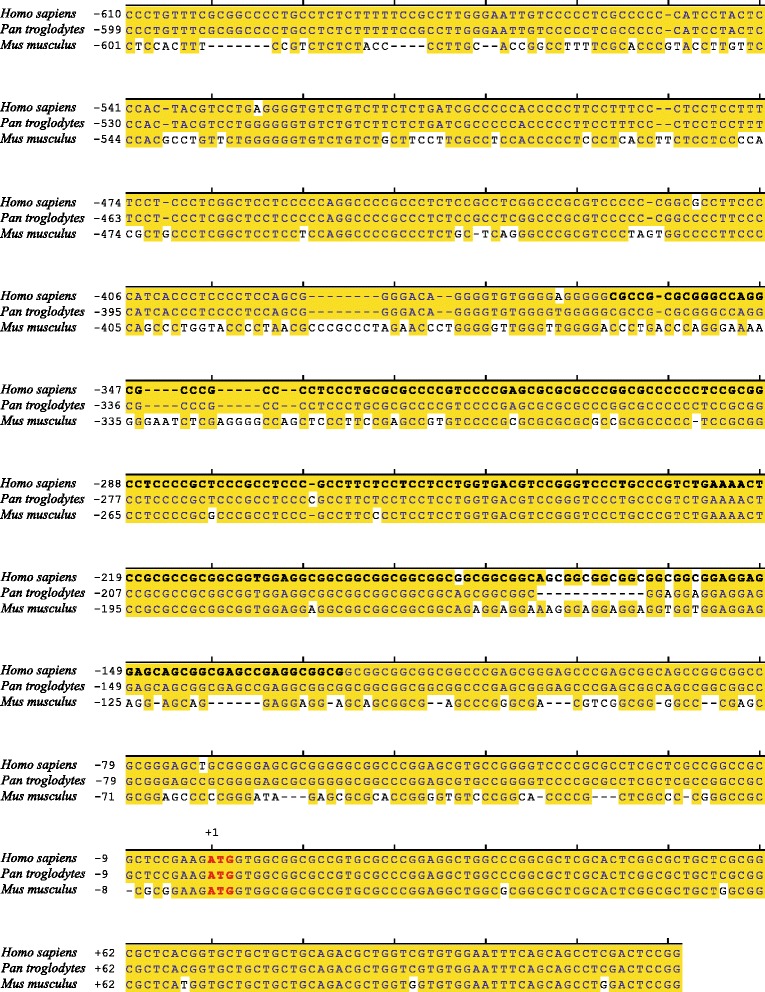

An evolutionary species alignment of the PCR A fragment (c.-610 to c.+122) represented a strong overlap of human promoter sequence XYLT1complete [GenBank Accession Number KM079589] with corresponding DNA fragments of related species Pan troglodytes [GenBank Accession Number NC_006483.3] and Mus musculus [GenBank Accession Number NC_000073.6]. While the compliance of the whole genomic XYLT1 promoter sequences between Homo sapiens (c.-1877 to c. + 1) and Pan troglodytes assessed as 98%, the compliance of XYLT1238* (c.-363 to c.-126) was 93% (Figure 2). Corresponding sequence conformity of Homo sapiens and Mus musculus sequences amounted to 58% in the whole and to 77% concerning XYLT1238*.

Figure 2.

Cross-species sequence alignment of the XYLT1 promoter sequence c.-610 to c.+122. Genomic DNA sequences of Homo sapiens (XYLT1 complete, [GenBank Accession Number KM079589]), Pan troglodytes [GenBank Accession Number NC_006483.3] and Mus musculus [GenBank Accession Number NC_000073.6] have been compared. Numbers indicate the nucleotide position up- or downstream of the translation initiation site ATG (red color). Matching nucleotides are shaded in yellow, whereas XYLT1 238* (c.-363 to c.-126) is marked in bold.

Characterization of the XYLT1 promoter fragment XYLT1238*

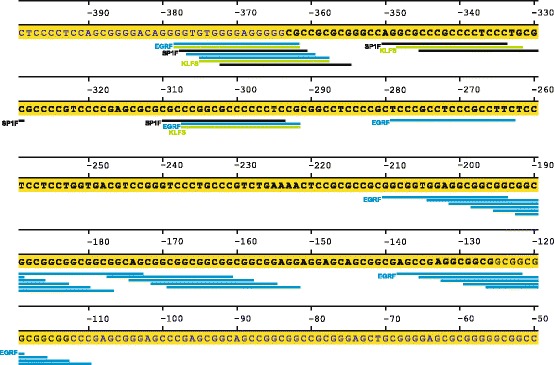

XYLT1238* displays a GC content of 84.9% and harbors a variable microsatellite region (c.-201 to c.-148). To identify putative transcription factor binding sites, an in silico analysis was performed. Search criteria were restricted to families of transcription factors, which have been discussed to modulate XT or which are known mediators of TGF-β1. As indicated in Figure 3, several transcription factor binding sites of transcriptions factor families SP1F (GC-box factors, specificity protein1), EGRF (early growth response/nerve growth factor induced protein C and related factors) and KLFS (krueppel like transcription factors) were identified.

Figure 3.

Localization of transcription factor binding sites in XYLT1 238* and appropriate flanking regions. Numbers indicate the nucleotide position downstream of the translation initiation site (ATG). XYLT1 238* (c.-363 to c.-126) is marked in bold, while transcription factor binding sites are highlighted in black (SP1F), blue (EGRF) or green (KLFS).

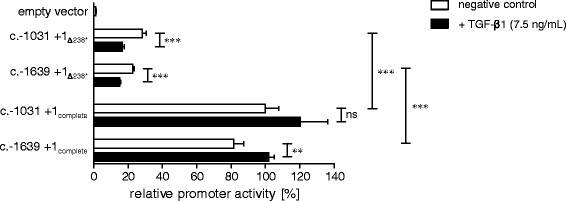

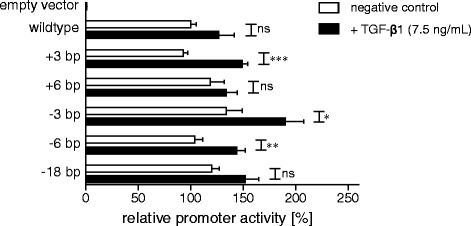

To evaluate the influence of XYLT1238* on promoter activity, appropriate promoter luciferase constructs were cloned by insertion of XYLT1238* in existing XYLT1 promoter coding luciferase vectors using site-directed mutagenesis. These plasmid constructs were originally synthesized for initial promoter characterization [16] and include the entire, but as we could define incomplete, promoter region c.-1639 to c.+1Δ238* or the most active promoter segment c.-1031 to c.+1Δ238* according to the XYLT1 reference sequence [GenBank Accession Number NG_015843.1]. After plasmid transfection into SW1353 chondrosarcoma cells and subsequent performing of a dual luciferase assay, promoter activity was shown to become significantly upregulated by insertion of XYLT1238*. Comparing promoter activity of constructs c.-1639 to c.+1Δ238* and c.-1031 to c.+1Δ238* to the vectors c.-1639 to c.+1complete and c.-1031 to c.+1complete revealed a significant increase of 22.6% (±0.9% SEM) to 81.6% (±5.6% SEM) or 28.3% (±2.2% SEM) to 100.0% (±1.1 %SEM), respectively (Figure 4, white bars). To analyze the putative inducibility of the XYLT1 promoter activity by TGF-β1, SW1353 cells were transfected as described above, followed by incubation with cell culture medium supplemented with TGF-β1 for 48 h. While no increase in promoter activity was detected for constructs c.-1639 to c.+1Δ238* and c.-1031 to c.+1Δ238* in comparison to untreated controls, promoter activity of constructs c.-1639 to c.+1complete and c.-1031 to c.+1complete enlarged from 100% (±1.1% SEM) to 120.2% (±16.2% SEM) or 81.6% (± 5.6% SEM) to 101.7% (±3.2% SEM), respectively (Figure 4, black bars).

Figure 4.

Influence of XYLT1 238* on promoter activity. Changes in relative promoter activity of pGL4.10 XYLT1 promoter cloning constructs were determined in response to insertion of XYLT1 238* by site-directed mutagenesis. Promoter activities are expressed relative to the activity of construct c.-1031 to c.+1complete, which was defined as 100%. Plasmids were transfected into SW1353 cells and promoter activity was determined in lysates of untreated (white bars) or TGF-β1 induced (black bars) cells by dual luciferase assay. Values are means ± SEM of triplicates from at least two or three independent experiments. ns = not significant; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (Mann-Whitney U-test).

SNV analysis

In addition to identification of XYLT1238*, genotyping of the complete promoter region revealed two SNV. Allele frequencies of c.-403C>T and c.-1088C>A were determined in DNA samples of 100 healthy blood donors (Table 2). All genotype distributions accorded with the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, whereas haplotype analysis depicted a weak linkage disequilibrium (D’ = 0.85; r2 = 0.49; haplotypes Table 3).

Table 2.

Allele frequencies of XYLT1 promoter SNV detected in healthy blood donors

| SNV | rs ID | Allele | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| c.-403C>T | rs118030014 | C | 104/200 (0.52) |

| T | 96/200 (0.48) | ||

| c.-1088C>A | rs59423557 | C | 124/200 (0.62) |

| A | 76/200 (0.38) |

Table 3.

Estimated XYLT1 haplotypes detected in healthy blood donors

| Haplotype | c.-403 | c.-1088 | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C | C | 98/200 (0.492) |

| 2 | T | A | 70/200 (0.352) |

| 3 | T | C | 26/200 (0.128) |

| 4 | C | A | 6/200 (0.028) |

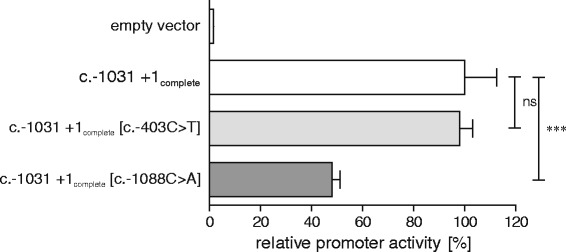

By performing an in silico analysis, it could be demonstrated that the base exchange c.-1088C>A entails the presence of a SMAD3 transcription factor binding site (reverse strand; 5′-GTCTGG-3’). After selective mutation of the cloning luciferase vector c.-1031 to c.+1complete by site-directed mutagenesis according to the SNV genotype, SNV associated changes in promoter activity were analyzed (Figure 5). c.-403T did not exert any influence on promoter activity, whereby the mutation c.-1088A was followed by a significant reduction in activity to 48.1% (± 3.0% SEM). Contrarily, quantification of serum XT activity did not reveal any association between SNV genotype and serum XT activity (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Influence of SNV on promoter activity. Changes in relative promoter activity of pGL4.10 XYLT1 promoter cloning construct c.-1031 to c.+1complete were determined in response to SNV-associated base exchange by site-directed mutagenesis. Promoter activities are expressed relative to the activity of construct c.-1031 to c.+1complete, which was defined as 100%. Plasmids were transfected into SW1353 cells and promoter activity was determined by dual luciferase assay. Values are means ± SEM of triplicates from at least two or three independent experiments. ns = not significant; ***p < 0.001 (Mann-Whitney U-test).

Identification and characterization of a microsatellite in the XYLT1 promoter region

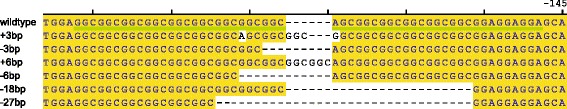

XYLT1238* characterization also uncovered a variable microsatellite (c.-201 to c.-148). Genotyping of 100 healthy blood donors revealed that 55% of blood donors were heterozygous carriers of this microsatellite, while 45% were homozygous carriers. In addition to the wildtype, five homozygous variants of the microsatellite were identified, distinguishable by different numbers of tandem repeats (GGX)n (Figure 6). Allele frequencies are listed in Table 4. The more tandem repeats were coded in the microsatellite variant, the more EGR-1 transcription factor binding sites are strung together (Figure 3). Due to sequence chromatogram overlaps, heterozygous genotypes were definable neither by Sanger nor by pyro sequencing.

Figure 6.

Microsatellite sequence variants. Naturally occurring variants of the XYLT1 promoter region c.-211 to c.-145 are illustrated. Numbering c.-145 indicates the nucleotide position upstream of the translation initiation site, whereas numbers on the left indicate the tandem-repeat pattern. Matching nucleotides between variants are shaded in yellow. The microsatellite locus is highlighted in green.

Table 4.

Allele frequencies of homozygous microsatellite variants detected in healthy blood donors

| Homozygous microsatellite variant | Frequency |

|---|---|

| wildtype | 27/45 |

| + 3 bp | 5/45 |

| - 3 bp | 2/45 |

| + 6 bp | 1/45 |

| - 6 bp | 9/45 |

| - 18 bp | 1/45 |

Referring to SNV analysis, we also tested the influence of microsatellite variants on promoter activity. For this purpose, variants were cloned into the luciferase promoter construct c.-1031 to c.+1complete by site-directed mutagenesis. Determination of relative promoter activity by dual luciferase assay in SW1353 cells depicted no dependency of tandem repeat length on promoter activity (Figure 7). Nevertheless, construct associated changes in promoter activity were detected. In addition to basal promoter activity, inducibility of microsatellite variant constructs by TGF-β1 was analyzed. Although the promoter activity of all constructs was significantly increased, no obvious trend in construct associated promoter activity difference was identifiable.

Figure 7.

Influence of microsatellite variants on promoter activity. Changes in relative promoter activity of pGL4.10 XYLT1 promoter cloning construct c.-1031 to c.+1complete (wildtype) were determined in response to insertion of microsatellite variants by site-directed mutagenesis. Promoter activities are expressed relative to the activity of construct c.-1031 to c.+1complete, which was defined as 100%. Plasmids were transfected into SW1353 cells and promoter activity was determined in lysates of untreated (white bars) or TGF-β1 induced (black bars) cells by dual luciferase assay. Values are means ± SEM of triplicates from at least two or three independent experiments. ns = not significant; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (Mann-Whitney U-test).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to figure out transcriptional regulation mechanisms of XT-I. Therefore, the genomic DNA of healthy blood donors was screened for sequence variants in the human XYLT1 promoter region to determine their influence on the naturally occurring variability of serum XT activity and to evaluate the promoter conservation. XT-I, the key enzyme of proteoglycan synthesis, is not only upregulated in the case of fibrotic remodeling, but is also associated with osteoarthritis and ossification disorders [11,12,24]. The clinical relevance of XT-I is based on its capability to represent the proteoglycan turn-over rate as a serum biomarker [25]. Hence, an increasing knowledge of its transcriptional regulation pathways will contribute to the elucidation of underlying pathomechanisms.

At present, only two publications concern the human XYLT1 promoter region. One of them describes the initial promoter identification and characterization. Due to the high GC content, cloning was based on gene synthesis of the first 600 bp upstream of the translational start codon according to the current XYLT1 reference sequence [GenBank Accession Number NG_015843.1] [16]. Another research project deals with the investigation of XYLT1 promoter activity regulation by IL-1β. As indicated, promoter deletion constructs were cloned by single fragment promoter amplification [26].

In this study, the first sequence analysis of the complete XYLT1 promoter region was performed. Surprisingly, we were not able to fully reproduce the current XYLT1 reference sequence [GenBank Accession Number NG_015843.1] but rather found out that the XYLT1 promoter is larger than expected and harbors a hitherto undescribed fragment of 238 bp, termed XYLT1238* [GenBank Accession Number KM079589]. To confirm this, we performed an in silico analysis revealing undeniable compliance of one single human shotgun sequence [GenBank Accession Number NW_001838365.2]. Interruption of the shotgun sequence reflects severity in amplification of this promoter fragment. In this study, successful amplification was only achievable by choosing slowdown-PCR conditions [18,19]. Molecular circumstances causing difficulties in amplification are uncertain. Speculatively, DNA secondary structures are involved in complex DNA assembly. We identified a potential structure of a G-quadruplex in the XYLT1 promoter (c.-387 to c.-364). G-quadruplex elements are known to influence transcriptional regulation and may be loosened by addition of PCR amplification additives in vitro [27,28]. Here, dc7GTP was used to minimize hogsteen base pairing in the G-quadruplex structure [29].

However, a high percentage match was detected by a cross-species alignment of the complete human XYLT1 promoter sequence XYLT1complete described here with sequences of Pan troglodytes [GenBank Accession Number NC_006483.3] and Mus musculus [GenBank Accession Number NC_000073.6]. Based on the evolutionary similarity of Homo sapiens and Pan troglodytes genomes [30], the reported promoter sequence XYLT1complete becomes strongly reinforced. Thus, we suggest a revision of the current XYLT1 reference sequence.

Characterization of XYLT1238* demonstrated a critical influence on basal transcriptional activity, as well as inducibility of XT-I by TGF-β1. Until now, studies have described an induction of XYLT1 mRNA expression in fibrotic tissues or after incubation of cultivated cells with TGF-β1 [9,10], whereas induction of promoter activity has remained elusive. Hence, this is the first study unravelling transcriptional mechanisms of XT-I induction. Several mediators like, for instance, transcription factors of the EGRF-, SP1- or KLFS-family were identified to regulate transcription. They all are associable with the manifestation of fibrotic disorders [31,32]. The most frequent transcription factor binding site in XYLT1238*, which was elicited in silico, binds EGR1 (early growth response protein 1). EGR1 functions as a downstream mediator of TGF-β1 and is responsible for a SMAD-independent increase in collagen mRNA expression in systemic sclerosis [33,34].

Sequence analysis of the genomic DNA of 100 healthy blood donors revealed the occurrence of a microsatellite as well as two SNV in the XYLT1 promoter region, and points to a strong conservation. This hypothesis is confirmed by the description of only a few SNV, representing risk factors for proteoglycan-associated pathologies like diabetic nephropathy, and two extremely rare, naturally occurring defects in the XYLT1 gene so far [24,35,36]. The homozygous missense mutation c.1441C>T (p.R481W) was elucidated to evoke functional enzymatic alterations causing intellectual disability and dwarfism [12]. In addition, five XYLT1-mutations were identified in patients suffering from Desbuquois dysplasia type 2, which is defined by pathological ossification [13]. Therefore, strong conservation of promoter and protein-coding genomic sequences of XYLT1 emphasizes its important physiological function.

In terms of the detected, genetically unlinked, SNV c.-403C>T and c.-1088C>A, a significant impairment of promoter activity was associated with homozygous nucleotide exchange c.-1088A. As indicated by in silico analysis, the mutation suggests generation of a SMAD3 transcription binding site. Nevertheless, SMAD3 is a cytoplasmatic mediator of TGF-β1 and should induce rather than reduce XYLT1 promoter activity [37]. Thus, the effect of c.-1088A on promoter activity should be further verified. Contrarily, no association between SNV genotypes and changes in serum XT activity of healthy blood donors was obtained. Hence, the identified SNV might contribute to differences in XYLT1 mRNA level but did not impact enzyme activity. It must be further investigated if changes in promoter activity correlate with changes in mRNA levels. Besides, XT-I may only marginally contribute to cumulative serum XT activity. This hypothesis is underlined by studies of Condac et al., who recently postulated that XT-II is the predominant XT-isoenzyme in serum [38].

Concerning the microsatellite in the XYLT1 promoter region, five homozygous variants were identified in addition to the wildtype genotype. Microsatellites consisting of (GGX)n tandem repeats are quite common in the human genome, especially in 5′ untranslated regions [39]. Nevertheless, it has to be emphasized that 55% of screened sequences were heterozygous, whereby corresponding allele types could not be resolved by standard sequencing. Future studies should deal with the exact genotyping. We further investigated the influence of the microsatellite variants on transcriptional regulation. Referring to promoter activity studies, a construct dependent variability of promoter activity was detected. However, a dependency of tandem repeat count was detected neither to basal nor TGF-β1 induced expression. Similar results were obtained by Akai et al., characterizing a microsatellite in the promoter region of collagen type 2 (COL1A2) [40]. Whether XYLT1 gene expression is significantly influenced by microsatellite variants in vivo was not part of this study, due to inappropriate cohort size, and needs to be further evaluated.

Conclusions

In summary, we describe here the first sequence analysis of the human XYLT1 promoter region. Based on our findings, we propose a revision of the current human XYLT1 promoter reference sequence. Our results provide new insights into transcriptional XT-I regulation. In future, genotyping of patients suffering from XT-associated diseases might uncover a potentially link between pathologic XT regulation and XYLT1 promoter sequence variants.

Availability of supporting data

The data set supporting the results of this study is included within the article. Genotypic data are available upon request depending on a signed declaration of exclusive research purpose.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dagmar Akkermann for her excellent technical assistance and Sarah L. Kirkby for her linguistic advice. This study was not supported by any funding source.

Abbreviations

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- EGRF

Early growth response/nerve growth factor induced protein C and related factors

- KLFS

Krueppel like transcription factors

- SDM

Site-directed mutagenesis

- SNV

Single nucleotide variant

- SP1F

GC-box factors, specificity protein1

- TGF-β1

Transforming growth factor-β1

- XT

Xylosyltransferase

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

IF conducted the experiments, analyzed data and wrote the paper. KOB, CL and JK conducted some experiments, analyzed data and discussed the manuscript. DH and CK designed, initiated and supervised the study and contributed to write the paper. All authors have been involved in drafting the manuscript, revised it critically and approved the submitted manuscript to be published.

Contributor Information

Isabel Faust, Email: ifaust@hdz-nrw.de.

Kai Oliver Böker, Email: kboeker@hdz-nrw.de.

Christoph Lichtenberg, Email: clichtenberg@hdz-nrw.de.

Joachim Kuhn, Email: jkuhn@hdz-nrw.de.

Cornelius Knabbe, Email: cknabbe@hdz-nrw.de.

Doris Hendig, Email: dhendig@hdz-nrw.de.

References

- 1.Götting C, Kuhn J, Zahn R, Brinkmann T, Kleesiek K. Molecular cloning and expression of human UDP-d-Xylose:proteoglycan core protein beta-d-xylosyltransferase and its first isoform XT-II. J Mol Biol. 2000;304(4):517–528. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cuellar K, Chuong H, Hubbell SM, Hinsdale ME. Biosynthesis of chondroitin and heparan sulfate in chinese hamster ovary cells depends on xylosyltransferase II. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(8):5195–5200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611048200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kjellen L, Lindahl U. Proteoglycans: structures and interactions. Annu Rev Biochem. 1991;60:443–475. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.60.070191.002303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heinegard D. Proteoglycans and more–from molecules to biology. Int J Exp Pathol. 2009;90(6):575–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2009.00695.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asano Y. Future treatments in systemic sclerosis. J Dermatol. 2010;37(1):54–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2009.00758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hinz B, Phan SH, Thannickal VJ, Prunotto M, Desmouliere A, Varga J, De Wever O, Mareel M, Gabbiani G. Recent developments in myofibroblast biology: paradigms for connective tissue remodeling. Am J Pathol. 2012;180(4):1340–1355. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuhn J, Gressner OA, Götting C, Gressner AM, Kleesiek K. Increased serum xylosyltransferase activity in patients with liver fibrosis. Clin Chim Acta. 2009;409(1–2):123–126. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Götting C, Sollberg S, Kuhn J, Weilke C, Huerkamp C, Brinkmann T, Krieg T, Kleesiek K. Serum xylosyltransferase: a new biochemical marker of the sclerotic process in systemic sclerosis. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;112(6):919–924. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prante C, Milting H, Kassner A, Farr M, Ambrosius M, Schön S, Seidler DG, Banayosy AE, Körfer R, Kuhn J, Kleesiek K, Götting C. Transforming growth factor beta1-regulated xylosyltransferase I activity in human cardiac fibroblasts and its impact for myocardial remodeling. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(36):26441–26449. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702299200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faust I, Roch C, Kuhn J, Prante C, Knabbe C, Hendig D. Human xylosyltransferase-I - A new marker for myofibroblast differentiation in skin fibrosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;436(3):449–454. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.05.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Venkatesan N, Barre L, Bourhim M, Magdalou J, Mainard D, Netter P, Fournel-Gigleux S, Ouzzine M. Xylosyltransferase-I regulates glycosaminoglycan synthesis during the pathogenic process of human osteoarthritis. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e34020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schreml J, Durmaz B, Cogulu O, Keupp K, Beleggia F, Pohl E, Milz E, Coker M, Ucar SK, Nürnberg G, Nürnberg P, Kuhn J, Ozkinay F. The missing “link”: an autosomal recessive short stature syndrome caused by a hypofunctional XYLT1 mutation. Hum Genet. 2013;133(1):29–39. doi: 10.1007/s00439-013-1351-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bui C, Huber C, Tuysuz B, Alanay Y, Bole-Feysot C, Leroy JG, Mortier G, Nitschke P, Munnich A, Cormier-Daire V. XYLT1 Mutations in Desbuquois Dysplasia Type 2. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94(3):405–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pönighaus C, Ambrosius M, Casanova JC, Prante C, Kuhn J, Esko JD, Kleesiek K, Götting C. Human xylosyltransferase II is involved in the biosynthesis of the uniform tetrasaccharide linkage region in chondroitin sulfate and heparan sulfate proteoglycans. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(8):5201–5206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611665200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roch C, Kuhn J, Kleesiek K, Götting C. Differences in gene expression of human xylosyltransferases and determination of acceptor specificities for various proteoglycans. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;391(1):685–691. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.11.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Müller B, Prante C, Kleesiek K, Götting C. Identification and characterization of the human xylosyltransferase I gene promoter region. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(45):30775–30782. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.016592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Müller B, Prante C, Knabbe C, Kleesiek K, Götting C. First identification and functional analysis of the human xylosyltransferase II promoter. Glycoconj J. 2013;30(3):237–245. doi: 10.1007/s10719-012-9439-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frey UH, Bachmann HS, Peters J, Siffert W. PCR-amplification of GC-rich regions: ‘slowdown PCR’. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(8):1312–1317. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bachmann HS, Siffert W, Frey UH. Successful amplification of extremely GC-rich promoter regions using a novel ‘slowdown PCR’ technique. Pharmacogenetics. 2003;13(12):759–766. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200312000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geiser M, Cebe R, Drewello D, Schmitz R. Integration of PCR fragments at any specific site within cloning vectors without the use of restriction enzymes and DNA ligase. Biotechniques. 2001;31(1):88. doi: 10.2144/01311st05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell P, Jacobsson I, Benzing-Purdie L, Roden L, Fessler JH. Silk-a new substrate for UDP-d-xylose:proteoglycan core protein beta-D-xylosyltransferase. Anal Biochem. 1984;137(2):505–516. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weilke C, Brinkmann T, Kleesiek K. Determination of xylosyltransferase activity in serum with recombinant human bikunin as acceptor. Clin Chem. 1997;43(1):45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(2):263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schön S, Huep G, Prante C, Müller S, Christ R, Hagena FW, Kuhn J, Kleesiek K, Götting C. Mutational and functional analyses of xylosyltransferases and their implication in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14(5):442–448. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Götting C, Kuhn J, Sollberg S, Huerkamp C, Brinkmann T, Krieg T, Kleesiek K. Elevated serum xylosyltransferase activity correlates with a high level of hyaluronate in patients with systemic sclerosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2000;80(1):60–61. doi: 10.1080/000155500750012612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khair M, Bourhim M, Barre L, Li D, Netter P, Magdalou J, Fournel-Gigleux S, Ouzzine M. Regulation of xylosyltransferase I gene expression by interleukin 1beta in human primary chondrocyte cells: mechanism and impact on proteoglycan synthesis. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(3):1774–1784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.419887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burge S, Parkinson GN, Hazel P, Todd AK, Neidle S. Quadruplex DNA: sequence, topology and structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(19):5402–5415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qin Y, Hurley LH. Structures, folding patterns, and functions of intramolecular DNA G-quadruplexes found in eukaryotic promoter regions. Biochimie. 2008;90(8):1149–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jung A, Ruckert S, Frank P, Brabletz T, Kirchner T. 7-Deaza-2′-deoxyguanosine allows PCR and sequencing reactions from CpG islands. Mol Pathol. 2002;55(1):55–57. doi: 10.1136/mp.55.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Britten RJ. Divergence between samples of chimpanzee and human DNA sequences is 5%, counting indels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(21):13633–13635. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172510699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hitraya EG, Varga J, Artlett CM, Jimenez SA. Identification of elements in the promoter region of the alpha1(I) procollagen gene involved in its up-regulated expression in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(11):2048–2058. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199811)41:11<2048::AID-ART21>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holian J, Qi W, Kelly DJ, Zhang Y, Mreich E, Pollock CA, Chen XM. Role of Kruppel-like factor 6 in transforming growth factor-beta1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition of proximal tubule cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295(5):F1388–1396. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00055.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen SJ, Ning H, Ishida W, Sodin-Semrl S, Takagawa S, Mori Y, Varga J. The early-immediate gene EGR-1 is induced by transforming growth factor-beta and mediates stimulation of collagen gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(30):21183–21197. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603270200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhattacharyya S, Chen SJ, Wu M, Warner-Blankenship M, Ning H, Lakos G, Mori Y, Chang E, Nihijima C, Takehara K, Feghali-Bostwick C, Varga J. Smad-independent transforming growth factor-beta regulation of early growth response-1 and sustained expression in fibrosis: implications for scleroderma. Am J Pathol. 2008;173(4):1085–1099. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schön S, Prante C, Müller S, Schöttler M, Tarnow L, Kuhn J, Kleesiek K, Götting C. Impact of polymorphisms in the genes encoding xylosyltransferase I and a homologue in type 1 diabetic patients with and without nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2005;68(4):1483–1490. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schön S, Prante C, Bahr C, Tarnow L, Kuhn J, Kleesiek K, Götting C. The xylosyltransferase I gene polymorphism c.343G > T (p.A125S) is a risk factor for diabetic nephropathy in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(10):2295–2299. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verrecchia F, Mauviel A. Transforming growth factor-beta signaling through the Smad pathway: role in extracellular matrix gene expression and regulation. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118(2):211–215. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.01641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Condac E, Dale GL, Bender-Neal D, Ferencz B, Towner R, Hinsdale ME. Xylosyltransferase II is a significant contributor of circulating xylosyltransferase levels and platelets constitute an important source of xylosyltransferase in serum. Glycobiology. 2009;19(8):829–833. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwp058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wren JD, Forgacs E, Fondon JW, 3rd, Pertsemlidis A, Cheng SY, Gallardo T, Williams RS, Shohet RV, Minna JD, Garner HR. Repeat polymorphisms within gene regions: phenotypic and evolutionary implications. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67(2):345–356. doi: 10.1086/303013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akai J, Kimura A, Hata RI. Transcriptional regulation of the human type I collagen alpha2 (COL1A2) gene by the combination of two dinucleotide repeats. Gene. 1999;239(1):65–73. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(99)00380-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]