Abstract

BACKGROUND

Co-trimoxazole (fixed-dose trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole) prophylaxis administered before antiretroviral therapy (ART) reduces morbidity in children infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). We investigated whether children and adolescents receiving long-term ART in sub-Saharan Africa could discontinue co-trimoxazole.

METHODS

We conducted a randomized, noninferiority trial of stopping versus continuing daily open-label co-trimoxazole in children and adolescents in Uganda and Zimbabwe. Eligible participants were older than 3 years of age, had been receiving ART for more than 96 weeks, were using insecticide-treated bed nets (in malaria-endemic areas), and had not had Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia. Coprimary end points were hospitalization or death and adverse events of grade 3 or 4.

RESULTS

A total of 758 participants were randomly assigned to stop or continue co-trimoxazole (382 and 376 participants, respectively), after receiving ART for a median of 2.1 years (interquartile range, 1.8 to 2.3). The median age was 7.9 years (interquartile range, 4.6 to 11.1), and the median CD4 T-cell percentage was 33% (interquartile range, 26 to 39). Participants who stopped co-trimoxazole had higher rates of hospitalization or death than those who continued (72 participants [19%] vs. 48 [13%]; hazard ratio, 1.64; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.14 to 2.37; P = 0.007; noninferiority not shown). There was no evidence of variation across ages (P = 0.93 for interaction). A total of 2 participants in the prophylaxis-stopped group (1%) died, as did 3 in the prophylaxis-continued group (1%). Most hospitalizations in the prophylaxis-stopped group were for malaria (49 events, vs. 21 in the prophylaxis-continued group) or infections other than malaria (53 vs. 25), particularly pneumonia, sepsis, and meningitis. Rates of adverse events of grade 3 or 4 were similar in the two groups (hazard ratio, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.83 to 1.72; P = 0.33), but more grade 4 adverse events occurred in the prophylaxis-stopped group (hazard ratio, 2.04; 95% CI, 0.99 to 4.22; P = 0.05), with anemia accounting for the largest number of events (12, vs. 2 with continued prophylaxis).

CONCLUSIONS

Continuing co-trimoxazole prophylaxis after 96 weeks of ART was beneficial, as compared with stopping prophylaxis, with fewer hospitalizations for both malaria and infection not related to malaria. (Funded by the United Kingdom Medical Research Council and others; ARROW Current Controlled Trials number, ISRCTN24791884.)

Co-trimoxazole (fixed-dose trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole) is commonly used in sub-Saharan Africa because of its low cost, wide availability, and broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity. Despite high levels of resistance to co-trimoxazole, prophylaxis with this drug combination before antiretroviral therapy (ART) reduces mortality, morbidity, and rates of hospitalization among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected adults1-6 and children,7,8 predominantly by reducing rates of pneumonia, diarrhea, and malaria.1-8

The increasing availability of ART in sub-Saharan Africa has considerably reduced morbidity and mortality among HIV-infected children.9 World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines10 recommend daily co-trimoxazole prophylaxis for HIV-infected children younger than 2 years of age and for those older than 2 years of age who have symptomatic disease or CD4 T-cell counts below age-related thresholds. However, the guidelines state that children older than 5 years of age who have good adherence to therapy during more than 6 months of ART, full clinical recovery, and a CD4 T-cell count of more than 350 per cubic millimeter may discontinue co-trimoxazole.11 These guidelines are based on expert opinion and supported by observational data from Europe12 and the United States13 showing that stopping co-trimoxazole with adequate CD4 T-cell recovery does not increase the risk of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia or serious bacterial infection. However, to our knowledge, there have been no trials of the discontinuation of co-trimoxazole therapy in children and there are no data from sub-Saharan Africa, where bacterial infections are common and malaria is frequently endemic.

A systematic review14 of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis along with the initiation of ART in HIV-infected adolescents (>13 years of age) and adults in resource-limited settings showed a reduction in mortality of 58% (95% confidence interval [CI], 39 to 71). However, because most studies had short follow-up, the duration of effective treatment could not be determined; the longest study (median follow-up, 4.9 years) showed survival benefits of co-trimoxazole during 72 weeks of ART but no effect thereafter.15 We report the effect of stopping versus continuing co-trimoxazole prophylaxis in children and adolescents who were receiving long-term ART in the Antiretroviral Research for Watoto (ARROW) trial16 in Uganda and Zimbabwe.

METHODS

STUDY DESIGN

In this open-label, randomized, parallel-group trial, we enrolled HIV-infected children and adolescents (≥3 years of age) who had been receiving ART within the ARROW trial for more than 96 weeks at three centers in Uganda and one in Zimbabwe; the complete trial protocol is available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org. Participants were receiving daily co-trimoxazole prophylaxis (once-daily doses of 200 mg of sulfamethoxazole and 40 mg of trimethoprim, 400 mg of sulfamethoxazole and 80 mg of trimethoprim, or 800 mg of sulfamethoxazole and 160 mg of trimethoprim for a body weight of 5 to 15, 15 to 30, or >30 kg, respectively) and had an insecticide-treated bed net if they were living in a malaria-endemic area. Children and adolescents with previous P. jirovecii pneumonia were excluded.

Participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to continue to receive or to stop receiving prophylaxis. The hypothesis was that among patients who were receiving long-term ART, the outcomes in the group that stopped receiving prophylaxis would be similar to the outcomes in the group that continued to receive prophylaxis (i.e., cessation of prophylaxis would be noninferior to continued prophylaxis). Caregivers and participants who were 18 years of age or older by the time they were enrolled in the current study provided written informed consent; children and adolescents 7 to 17 years of age gave assent (depending on their knowledge of HIV status).

The trial was approved by research ethics committees in Uganda, Zimbabwe, and the United Kingdom. ViiV Healthcare and GlaxoSmithKline donated antiretroviral agents. Co-trimoxazole was provided by national programs. The funders and medication donors had no role in any aspect of the study design, data accrual, data analysis, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Randomization was stratified according to trial center and according to the randomization assignments in the overarching ARROW trial (see the Supplementary Appendix, available at NEJM.org). The computer-generated, sequentially numbered randomization list (with variable block sizes) was prepared by the trial statistician and was incorporated within the secure database at each trial center. Randomization was performed by clinicians telephoning the local trial center. Trial managers could access the next number on the list but not the whole list.

Participants visited a doctor and underwent a full blood count, CD4 T-cell count, and liver-function and renal-function tests (measurements of bilirubin, urea, creatinine, aspartate aminotransferase, and alanine aminotransferase levels) at randomization and every 12 weeks thereafter. The participants had follow-up visits every 6 weeks with a nurse who used a standard symptom checklist; ART and co-trimoxazole adherence were assessed by means of self-reported answers to questions about missed doses. Follow-up of the participants in the two study groups was continued until trial closure.

END POINTS

Coprimary end points were a first hospitalization or death (efficacy) and adverse events of grade 3 or 4 that were not solely related to HIV infection (safety). Secondary end points included death, severe pneumonia, unexplained persistent diarrhea, clinical malaria, WHO stage 4 event or death, WHO stage 3 or 4 event or death, serious adverse events17 not solely related to HIV infection, growth (weight for age, height for age, and body-mass index for age), CD4 T-cell count, and adherence to ART (see the Supplementary Appendix). Clinical events and severe adverse events were reviewed according to WHO criteria18 by an end-point review committee whose chair and members were independent of the study personnel and were unaware of the study assignments.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

We estimated that a target sample of 947 participants followed for 1.5 to 2.5 years, with a loss to follow-up of less than 10%, would provide 80% power to establish that cessation of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis was noninferior to continued prophylaxis with respect to the primary efficacy end point (the rate of a first hospitalization or death). The noninferiority margin, chosen by a consensus of the investigators, was defined as the upper 95% confidence limit for a between-group difference of no more than 3 events per 100 participant-years, assuming a rate of 5 events per 100 participant-years among participants continuing to receive co-trimoxazole (see the Supplementary Appendix). Interim data were reviewed annually by an independent data-monitoring committee (two meetings), with the use of the Haybittle–Peto criterion.19

All primary and secondary end points other than growth, CD4 T-cell count, and adherence to ART were compared between the randomized groups with the use of Kaplan–Meier plots, log-rank tests, and proportional-hazards models (stratified according to the stratification factors at randomization), with time counted from randomization to the first event, the last clinical assessment, or March 16, 2012 (trial closure), whichever was earliest. All comparisons were performed in the population of participants who underwent randomization (intention-to-treat analysis). The P values presented are from tests of the null hypothesis of no difference in efficacy or safety between the randomized groups (i.e., tests of superiority); absolute differences in the event rates (with 95% confidence intervals) were estimated to explicitly address the original noninferiority hypothesis. Details of the statistical analyses are provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

RESULTS

RANDOMIZATION AND FOLLOW-UP

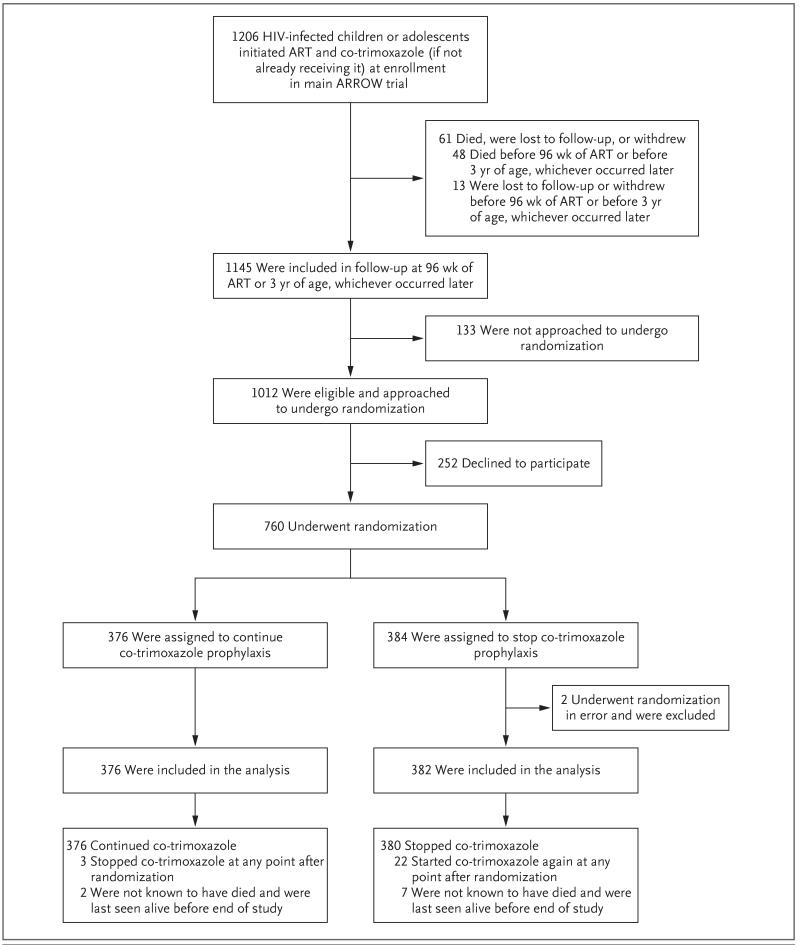

A total of 1012 participants in the ARROW trial were approached for randomization in the current trial (Fig. 1), of whom 252 were not randomly assigned to a trial group, in most cases because their caregivers strongly believed that co-trimoxazole was beneficial. From September 2009 through February 2011, a total of 384 participants were randomly assigned to stop receiving co-trimoxazole, and 376 were randomly assigned to continue receiving co-trimoxazole. Of the participants randomly assigned to stop receiving co-trimoxazole, 2 were receiving dapsone prophylaxis and were excluded from the analysis; 758 participants were included.

Figure 1. Study Enrollment, Randomization, and Follow-up.

Among 1145 participants in the Antiretroviral Research for Watoto (ARROW) trial who had received 96 weeks of antiretroviral therapy (ART) or were at least 3 years of age, 133 were not approached to undergo randomization (e.g., because the participant attended the clinic without a caregiver who could be approached to provide informed consent). A total of 252 participants in the ARROW trial were eligible for randomization but declined, predominantly because of strong caregiver beliefs in the benefits of co-trimoxazole. A total of 2 participants (both in the stop-treatment group) were receiving dapsone prophylaxis and had undergone randomization in error; they were not included in the analysis. A total of 5 participants were ineligible for this study but were nevertheless included in the analysis: 2 participants (both in the prophylaxis-continued group) had received less than 96 weeks of ART, and 3 (2 participants in the prophylaxis-stopped group and 1 in the prophylaxis-continued group) had received a diagnosis of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia; however, the diagnosis was not considered to be definitive, it occurred before enrollment, and it was not considered by the treating clinician to be plausible. In the prophylaxis-continued group, 1 participant temporarily discontinued co-trimoxazole at randomization and restarted it 1 month later. In the prophylaxis-stopped group, 3 participants continued to receive co-trimoxazole in error; 1 participant stopped prophylaxis 4 months after randomization, but the other 2 did not stop once the error was identified, owing to caregiver preference. In the prophylaxis-continued group, 3 participants stopped receiving co-trimoxazole (median duration of prophylaxis, 62 weeks [range, 42 to 78]); 2 participants stopped for approximately 6 weeks owing to clinic error, and 1 stopped intentionally when she became pregnant. In the prophylaxis-stopped group, 22 participants restarted co-trimoxazole (median duration until restarting, 30 weeks [range, 1 day to 95 weeks]).The reasons for restarting prophylaxis included caregiver concern (in the case of 14 participants) and clinician concern (in the case of 4: 1 with tuberculosis, 1 with P. jirovecii pneumonia, and 2 with low CD4 T-cell counts); prophylaxis was temporarily restarted in 2 patients owing to clinic or caregiver error, and no reason was provided for 2. The study ended on March 16, 2012; the minimum follow-up was 48 weeks in the prophylaxis-continued group and 30 weeks in the prophylaxis-stopped group.

Baseline characteristics were generally balanced between the two groups (Table 1, and Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). At randomization, participants had a median age of 7.9 years (interquartile range, 4.6 to 11.1); 11% of the participants were 13 years of age or older. In addition, participants had received ART for a median of 2.1 years (interquartile range, 1.8 to 2.3); 754 participants (99%) were receiving first-line ART. A total of 38 participants (5%) had CD4 T-cell percentages of less than 15% at randomization, the median CD4 T-cell percentage was 33% (interquartile range, 26 to 39), and the median CD4 T-cell count in those older than 5 years of age was 720 per cubic millimeter (interquartile range, 489 to 1055).

Table 1. Characteristics of the Participants at Randomization.*.

| Characteristic | Co-trimoxazole Prophylaxis Continued (N = 376) | Co-trimoxazole Prophylaxis Stopped (N = 382) |

|---|---|---|

| Female sex — no. (%) | 195 (52) | 203 (53) |

| Age — yr | ||

| Median | 7.5 | 8.3 |

| Interquartile range | 4.6 to 11.1 | 4.5 to 11.0 |

| Duration of ART — yr | ||

| Median | 2.1 | 2.1 |

| Interquartile range | 1.8 to 2.3 | 1.8 to 2.3 |

| Current ART regimen — no. (%)† | ||

| 3TC-ABC-NVP | 158 (42) | 139 (36) |

| 3TC-ABC-EFV | 90 (24) | 111 (29) |

| ZDV-3TC-ABC | 125 (33) | 126 (33) |

| Other first-line regimen | 1 (<1) | 4 (1) |

| LPV/r-containing second-line regimen | 2 (1) | 2 (1) |

| ART monitoring strategy — no. (%)‡ | ||

| Laboratory and clinical monitoring | 185 (49) | 189 (49) |

| Clinically driven monitoring | 191 (51) | 193 (51) |

| CD4 T cells — % | ||

| Before ART§ | ||

| Median | 13 | 12 |

| Interquartile range | 8 to 18 | 8 to 18 |

| Current | ||

| Median | 33 | 32 |

| Interquartile range | 26 to 39 | 26 to 39 |

| Current absolute CD4 T-cell count — cells/mm3 | ||

| 3–4 yr of age | ||

| Median | 1493 | 1512 |

| Interquartile range | 1011 to 1904 | 1099 to 1931 |

| 5–7 yr of age | ||

| Median | 1043 | 1091 |

| Interquartile range | 691 to 1432 | 709 to 1367 |

| 8–11 yr of age | ||

| Median | 710 | 695 |

| Interquartile range | 516 to 957 | 482 to 985 |

| ≥12 yr of age | ||

| Median | 567 | 562 |

| Interquartile range | 402 to 749 | 410 to 757 |

| Weight-for-age z score | ||

| Before ART§ | ||

| Median | −2.2 | −2.2 |

| Interquartile range | −3.2 to −1.3 | −3.3 to −1.3 |

| Current | ||

| Median | −1.3 | −1.3 |

| Interquartile range | −1.9 to −0.6 | −1.9 to −0.7 |

3TC denotes lamivudine, ABC abacavir, ART antiretroviral therapy, EFV efavirenz, LPV/r ritonavir-boosted lopinavir, NVP nevirapine, and ZDV zidovudine.

During randomization for ART within the overarching Antiretroviral Research for Watoto (ARROW) trial, ART was initiated with 3TC–ABC and a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI; either efavirenz or nevirapine) in one third of the participants and with ZDV–3TC–ABC and an NNRTI in two thirds. After 36 weeks, half the latter group discontinued ZDV and the other half discontinued the NNRTI (induction-maintenance strategy). NNRTIs were provided by local ministries of health. The regimen containing ritonavir-boosted lopinavir is a second-line therapy; other regimens listed are first-line therapies.

During randomization for the monitoring strategy within the overarching ARROW trial, participants were assigned to laboratory and clinical monitoring or to clinically driven monitoring alone. All the participants underwent CD4 T-cell, hematologic, and biochemical measurements every 12 weeks. All the results were returned for participants assigned to laboratory and clinical monitoring, but results were only returned for those assigned to clinically driven monitoring if they were requested for clinical reasons or if they indicated a grade 4 toxic event.

Measurements before the receipt of ART were conducted at the time of enrollment in the overarching ARROW trial.

The median follow-up from randomization to the date of trial closure or the last date on which the participant was known to be alive was 2.1 years (interquartile range, 1.8 to 2.2); the group in which prophylaxis was stopped had 763 participant-years of follow-up, as compared with 759 in the group that continued to receive prophylaxis. A total of nine participants withdrew from the study or were lost to follow-up (seven participants in the prophylaxis-stopped group and two in the prophylaxis-continued group) (Fig. 1).

A total of 96.0% of the participant-time in this study was spent not receiving co-trimoxazole in the prophylaxis-stopped group and 99.6% of the participant-time was spent receiving co-trimoxazole in the prophylaxis-continued group. A total of 2 participants (1%) randomly assigned to stop co-trimoxazole never stopped, and 3 (1%) randomly assigned to continue prophylaxis subsequently stopped; 22 participants (6%) randomly assigned to stop prophylaxis subsequently restarted it, mainly owing to concerns of the caregiver or clinician (Fig. 1). A total of 21 participants (3%) began receiving second-line ART.

EFFICACY END POINTS

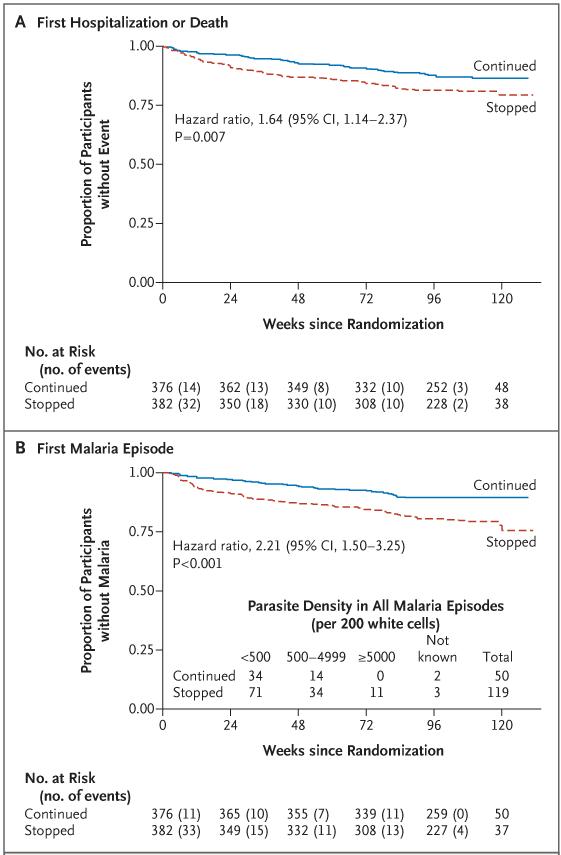

A total of 72 participants in the prophylaxis-stopped group (19%) as compared with 48 in the prophylaxis-continued group (13%) reached the coprimary efficacy end point of hospitalization or death (hazard ratio, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.14 to 2.37; P = 0.007 by the log-rank test; 6.8 vs. 10.8 events per 100 participant-years; difference, 4.0 events per 100 participant-years [95% CI, 0.8 to 7.2], which was outside the noninferiority margin) (Fig. 2A and Table 2, and Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). In prespecified subgroup analyses, there was no evidence (P>0.20 for interaction) that the efficacy of co-trimoxazole varied significantly according to age, sex, center, country, randomization year, baseline weight-for-age z score, CD4 T-cell count according to age, absolute CD4 T-cell count, or routine or clinically driven laboratory monitoring or first-line ART strategy (Table 2, and Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Figure 2. First Hospitalization or Death and First Diagnostically Confirmed Episode of Malaria in Participants Who Continued or Stopped Co-trimoxazole Prophylaxis.

All hazard ratios were stratified according to randomization factors, with P values calculated from the stratified log-rank test. The number of patients who would need to be treated with co-trimoxazole for 1 year to prevent a first hospitalization or death was 25 (Panel A); the number need to treat in order to prevent a first episode of malaria was 16 (Panel B).

Table 2. Primary and Secondary Time-to-Event End Points.

| End Point | Co-trimoxazole Prophylaxis Continued (N = 376) | Co-trimoxazole Prophylaxis Stopped (N = 382) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI)* | P Value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary efficacy end point: hospitalization or death — no. (%) | 48 (13) | 72 (19) | 1.64 (1.14–2.37) | 0.007 |

| According to CD4 T-cell percentage at randomization — no./total no. (%) | 0.08 | |||

| ≥30% | 23/237 (10) | 46/238 (19) | 2.15 (1.30–3.54) | |

| 15–29% | 19/126 (15) | 17/119(14) | 0.96 (0.50–1.85) | |

| 0–14% | 6/13 (46) | 9/25 (36) | 0.81 (0.29–2.27) | |

| According to ART monitoring strategy — no./ total no. (%) | 0.69 | |||

| CD4 T-cell monitoring | 21/185 (11) | 29/189 (15) | 1.44 (0.82–2.52) | |

| No CD4 T-cell monitoring | 27/191 (14) | 43/193 (22) | 1.67 (1.03–2.71) | |

| According to age at randomization — no./ total no. (%) | 0.93 | |||

| 3–6 yr | 24/176 (14) | 33/158 (21) | 1.69 (1.00–2.86) | |

| 7–12 yr | 18/162 (11) | 29/175 (17) | 1.53 (0.85–2.75) | |

| ≥13 yr | 6/38 (16) | 10/49 (20) | 1.38 (0.50–3.79) | |

| According to country — no./total no. (%) | 0.91 | |||

| Uganda | 40/283 (14) | 60/286 (21) | 1.59 (1.06–2.37) | |

| Zimbabwe | 8/93 (9) | 12/96 (12) | 1.51 (0.62–3.68) | |

| Hospitalization or death due to malaria — no. (%)‡ | 18 (5) | 36 (9) | 2.15 (1.22–3.78) | 0.007 |

| Hospitalization or death due to infection other than malaria — no. (%)J | 21 (6) | 39 (10) | 1.95 (1.15–3.32) | 0.01 |

| Malaria — no. (%) | 39 (10) | 77 (20) | 2.21 (1.50–3.25) | <0.001 |

| Primary safety end point: grade 3 or 4 adverse event — no. (%) | 55 (15) | 64 (17) | 1.20 (0.83–1.72) | 0.33 |

| Grade 4 adverse event — no. (%) | 11 (3) | 22 (6) | 2.04 (0.99–4.22) | 0.05 |

Hazard ratios were stratified according to center, monitoring group, and treatment group (i.e., the randomization stratification factors; unstratified hazard ratios were similar), except for subgroup analyses in which numbers within individual subgroups were too small for further stratification.

For subgroup analyses, the P values listed are for the test of heterogeneity. For other analyses, P values are for the log-rank test of stopping versus continuing prophylaxis.

Post hoc analyses included the two main components of the composite end point (hospitalization or death due to malaria, and hospitalization or death due to infection other than malaria). The numbers of participants do not add up to the total for the primary end point because a small number of participants were hospitalized for both malaria and infection other than malaria, and some were hospitalized only for a noninfectious disorder (Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Although there was some evidence of variation according to baseline CD4 T-cell percentage (P = 0.08 for interaction), the benefits of continued co-trimoxazole prophylaxis appeared to be greatest in participants with a CD4 T-cell percentage of 30% or more (hazard ratio for hospitalization or death in the prophylaxis-stopped group, 2.15; 95% CI, 1.30 to 3.54). The effects did not vary significantly over time (P = 0.14 by Schoenfeld’s test) (Fig. S1A in the Supplementary Appendix). A total of two participants in the prophylaxis-stopped group (1%) died (from infection other than malaria in both), as did three in the prophylaxis-continued group (1%) (all from a noninfectious disorder).

Including the first and subsequent hospitalizations, more hospitalizations and deaths occurred during follow-up in the prophylaxis-stopped group than in the prophylaxis-continued group (110 vs. 63 events), including hospitalizations for malaria (49 vs. 21) and for infection not related to malaria (53 vs. 25), particularly pneumonia, sepsis, and meningitis (Table S3 and Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). There was a trend toward more hospitalizations for severe malaria (grade 3 or 4 malaria, defined as prostration, coma, shock, or respiratory distress) among participants in the prophylaxis-stopped group (24 of 49 hospitalizations for malaria [49%]), as compared with the prophylaxis-continued group (6 of 21 [29%]) (P = 0.11 by the chi-square test). In post hoc analyses, stopping co-trimoxazole was associated with an increased risk of hospitalization or death due to malaria (hazard ratio, 2.15; 95% CI, 1.22 to 3.78; P = 0.007 by the log-rank test) and hospitalization or death due to infection other than malaria (hazard ratio, 1.95; 95% CI, 1.15 to 3.32; P = 0.01 by the log-rank test) (Table 2).

Malaria (diagnosed on the basis of characteristic microscopical findings or a positive result of a rapid diagnostic test) was observed only in Uganda and was more frequent in the prophylaxis-stopped group than in the prophylaxis-continued group (119 episodes in 77 participants [20%] vs. 50 episodes in 39 participants [10%]; hazard ratio, 2.21; 95% CI, 1.50 to 3.25; P<0.001 by the log-rank test) (Table 2 and Fig. 2B). The level of parasitemia was also higher in the prophylaxis-stopped group than in the prophylaxis-continued group (median parasite density per 200 white cells, 221 [interquartile range, 61 to 1507] vs. 153 [interquartile range, 23 to 710]; P = 0.04 by the rank-sum test). The increased risk after cessation of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis persisted, with no evidence of significant variation over time (P = 0.70 by Schoenfeld’s test); however, according to models explicitly estimating changes in risk over time,20 the excess risk appeared to be greatest early on (Fig. S1B in the Supplementary Appendix).

The frequency of other secondary end points was greater in the prophylaxis-stopped group than in the prophylaxis-continued group (Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix); however, because of the low event rates, most differences were not significant. Current or recent diarrhea was reported at follow-up visits in 57 participants in the prophylaxis-stopped group (15%), as compared with 38 participants in the prophylaxis-continued group (10%) (P=0.05 by the chi-square test).

SAFETY END POINTS

For the coprimary safety end point, there were 115 adverse events of grade 3 or 4 in 64 participants in the prophylaxis-stopped group (17%), as compared with 86 events in 55 participants in the prophylaxis-continued group (15%) (hazard ratio, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.83 to 1.72; P = 0.33 by the log-rank test) (Table 2, and Table S4 in the Supplementary Appendix). Of these events, 37 in the prophylaxis-stopped group were grade 4, as compared with 17 in the prophylaxis-continued group (hazard ratio, 2.04; 95% CI, 0.99 to 4.22; P = 0.05 by the log-rank test). The greatest excess in grade 4 adverse events was due to anemia (12 events in 10 participants in the prophylaxis-stopped group [3%] vs. 2 events in 2 participants in the prophylaxis-continued group [1%]; P = 0.04 by Fisher’s exact test) (Table S5 in the Supplementary Appendix). Only 1 participant (in the prophylaxis-stopped group) had adverse events of grade 3 or 4 (anemia, neutropenia, and presumed septicemia) that were adjudicated to be potentially related to co-trimoxazole; these events were also judged to be definitely related to zidovudine.

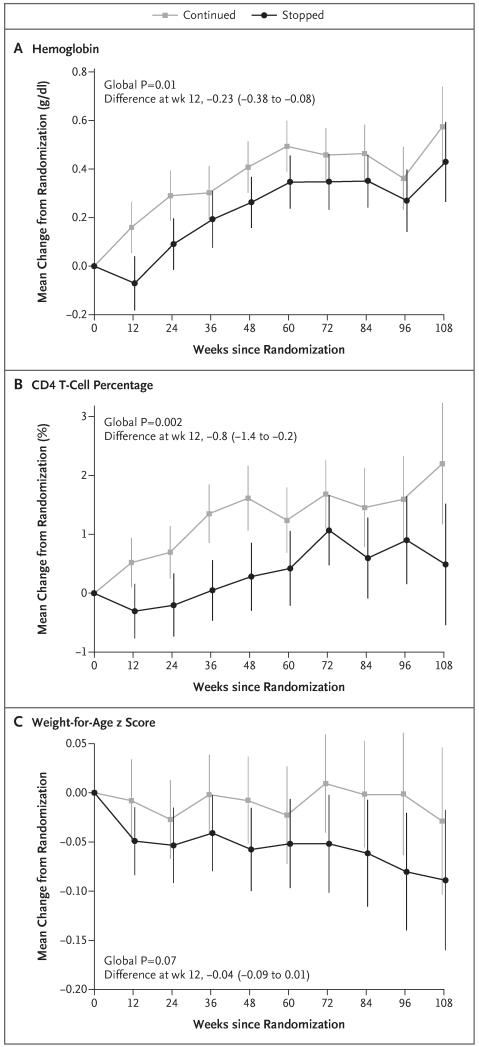

At 12 weeks after randomization, the hemoglobin level had increased from baseline in the prophylaxis-continued group but not in the prophylaxis-stopped group (mean [±SE] change, 0.16±0.05 vs. −0.07±0.06 g per deciliter; adjusted P = 0.003); the between-group difference attenuated after 12 weeks but remained significant overall (global P = 0.01 according to a generalized estimating equation that pools data across t-tests at each time point) (Fig. 3A). As compared with participants who continued to receive co-trimoxazole, those who stopped receiving it had greater increases in the white-cell count and neutrophil count at 12 weeks (adjusted P = 0.009 and 0.004, respectively) (Fig. S3A in the Supplementary Appendix) and subsequently (global P<0.001 for both comparisons).

Figure 3. Changes in Laboratory and Anthropometric Variables.

The between-group differences in changes from randomization to 12 weeks (prophylaxis-stopped group minus prophylaxis-continued group) are shown. Vertical lines indicate 95% confidence intervals.

The increase in the CD4 T-cell percentage was slower in the prophylaxis-stopped group than in the prophylaxis-continued group, particularly initially (adjusted P = 0.01 at week 12; global P = 0.002) (Fig. 3B), but there were no significant differences between the groups in absolute CD4 T-cell counts (global P = 0.98) (Fig. S3B in the Supplementary Appendix). There was a trend toward small reductions in the weight-for-age z score in participants who stopped receiving co-trimoxazole, as compared with those who continued to receive it (global P = 0.07) (Fig. 3C), but the height-for-age z score was similar in the two groups (global P = 0.19) (Fig. S3C in the Supplementary Appendix), as was the body-mass-index according to age (global P = 0.34).

There was no significant difference between the prophylaxis-stopped group and the prophylaxis-continued group with respect to ART adherence, as assessed on the basis of self-reported and caregiver-reported data at each follow-up visit for ART doses missed during the previous 4 weeks (mean percentage of participants with missed doses after randomization, 7% and 8%, respectively; global P = 0.21). Before randomization, similar proportions of participants in the prophylaxis-stopped group and the prophylaxis-continued group reported missed co-trimoxazole doses during the previous 4 weeks (mean, 5% and 6%, respectively; global P = 0.26), and this rate remained similar in the prophylaxis-continued group after randomization (mean, 6%). There were also no significant between-group differences in the number of missed doses over weekends or for 2 or more consecutive days (data not shown). During follow-up, the proportion of caregivers and participants in Uganda who reported bed-net use every night in the previous week was higher in the prophylaxis-stopped group than in the prophylaxis-continued group (mean, 99% vs. 98%; global P = 0.02).

DISCUSSION

In this randomized trial, we compared cessation of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis with continued prophylaxis in ART-treated children and adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa, where the frequency of bacterial and protozoal infections is high. The study participants who stopped receiving co-trimoxazole after more than 2 years of ART had low mortality but had a sustained increase in the number of hospitalizations for malaria and for infection other than malaria during more than 2 years of follow-up. There was no evidence of variation in the benefits of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis across ages or CD4 T-cell values — a finding that is in agreement with the results observed in adults in the Development of Antiretroviral Therapy in Africa trial.15

Existing recommendations11 regarding the discontinuation of co-trimoxazole in children in resource-limited settings are informed in part by observational data from high-income countries,12,13 where serious bacterial infections are less frequent, malaria is rare, and co-trimoxazole is primarily used to prevent P. jirovecii pneumonia. Once children in those locations have good recovery of CD4 T cells during ART, the risk of opportunistic infections is low and cessation of co-trimoxazole appears to be safe. However, we found that co-trimoxazole continues to provide protection against bacterial infections and malaria in sub-Saharan Africa, despite good immune reconstitution during long-term ART.

The increase in hospitalizations among the participants who stopped receiving co-trimoxazole was evident early and persisted throughout follow-up. It was observed in both a country where malaria is endemic (Uganda) and a country where malaria is not endemic (Zimbabwe). The risk of malaria requiring hospitalization, which was twice as high among participants who stopped receiving co-trimoxazole as it was among those who continued to receive co-trimoxazole, was consistent with previous studies showing that co-trimoxazole prevents parasitemia4 and clinical malaria.1,21-23 A randomized trial24 involving ART-treated adults in Uganda similarly showed increased risks of malaria after co-trimoxazole was discontinued. Although the potential for increased antifolate resistance has raised concerns about more widespread use of co-trimoxazole,25 most studies have not shown an increase in resistance22,26-28; where high-level resistance has emerged, antifolates such as sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine still appear to be effective.21 Furthermore, guidelines now recommend artemisinin-based first-line antimalarial treatment.29

In our study, participants who stopped receiving co-trimoxazole also had an increase in the number of hospitalizations for infection other than malaria, particularly pneumonia, septicemia, and meningitis — a finding that is consistent with the major reductions in bacterial infections observed with co-trimoxazole in pre-ART trials involving children7,8 and adults.1,6 Co-trimoxazole provided protection against invasive bacterial infection even in a patient population with a relatively high CD4 T-cell percentage (median, 33% in the ARROW trial vs. 11% in the Children with HIV Antibiotic Prophylaxis [CHAP] trial7). Our findings contrast with those of a previous observational U.S. study,13 which showed no increased risk of severe bacterial infection among ART-treated children who stopped receiving co-trimoxazole after good immune reconstitution. However, studies involving adults in Africa have shown that there is an ongoing risk of severe bacterial infection associated with relatively high CD4 T-cell counts.30-33 Maintaining prophylaxis against a wide spectrum of gram-positive and gram-negative organisms may therefore be important in sub-Saharan Africa, where rates of bacterial infection are high.

Like other studies,4,7,15,24 ours showed benefits from co-trimoxazole prophylaxis in two countries with high rates of resistance to co-trimoxazole, for reasons that are unclear. Co-trimoxazole may retain sufficient antimicrobial activity to prevent severe bacterial disease, or its activity against other pathogens, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis34 and P. jirovecii, may have been underestimated. Since diagnostic capacity in the ARROW trial was limited, the diagnosis of most cases of severe bacterial pneumonia was presumptive; although an end-point review committee adjudicated all diagnoses, it is possible that some participants had tuberculosis, P. jirovecii pneumonia, or infection due to another organism, as previously reported.35 We observed fewer cases of tuberculosis among participants who stopped receiving co-trimoxazole than among those who continued to receive it (Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix); however, most diagnoses of tuberculosis were presumptive, the numbers were small, and tuberculosis and bacterial coinfection is not unusual.35

One question is why the antibacterial activity of co-trimoxazole persists in children (those in our study had been receiving ART for 4 to 5 years by the date of trial closure) but wanes in adults.15 Children generally have a higher risk of bacterial infections than adults, and immune reconstitution is driven predominantly by repopulation with naive CD4 T cells in children36 but not in adults; children may therefore still have poor pathogen-specific memory responses despite long-term ART.

Stopping co-trimoxazole prophylaxis had no significant effect on growth in our study participants, in contrast to the improved growth observed among children who received co-trimoxazole, as compared with those who received placebo, in the CHAP trial, which involved HIV-infected children who were not receiving ART.37 Children have rapid weight and height increases during ART,9 particularly during the first year38; any additional benefit of co-trimoxazole after 2 years of ART may be minimal.

In our study, children and adolescents who stopped receiving co-trimoxazole had higher rates of anemia, including potentially life-threatening (grade 4) events, than those who continued co-trimoxazole. Although this may seem counterintuitive, it is consistent with the results of the CHAP trial, in which children receiving co-trimoxazole who had not previously received ART had greater increases in the hemoglobin level than those receiving placebo.37 The high frequency of infection, particularly malaria, in children who stopped receiving co-trimoxazole could explain the rates of anemia in the ARROW trial. Alternatively, co-trimoxazole may reduce the immune activation that impairs erythropoiesis,39 either directly by means of immunomodulatory properties or indirectly by reducing the translocation of intestinal microbes.15 The greater increases in white-cell and neutrophil counts in participants who stopped receiving co-trimoxazole, as compared with those who continued to receive it, are consistent with the potential myelosuppressive effects of co-trimoxazole.

The main limitation of our trial is the combination of the open-label design and the management-based primary end point (hospitalization). However, the open-label design had the advantage of reducing the pill burden in the prophylaxis-stopped group, thus allowing potential improvements in ART adherence to be evaluated. There was no cost to caregivers, so there was no bias from differences in the ability to pay for hospital care between groups. We cannot rule out differences in preventive or health-seeking behavior among caregivers or differences among clinicians in the threshold for hospitalizing a patient. More participants in the prophylaxis stopped group might have been hospitalized owing to concerns about the cessation of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis, although it is equally plausible that more participants in the prophylaxis continued group were hospitalized owing to concerns about breakthrough infection during prophylaxis. The consistency across multiple (including severe) end points and subgroups suggests an underlying effect. Even if the real effect is smaller than observed, co-trimoxazole is inexpensive, costing only a few cents per day.

Our findings highlight the importance of co-trimoxazole in treating HIV-infected children and adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa, even in the ART era. Current WHO recommendations11 — that co-trimoxazole prophylaxis can be stopped in children older than 5 years of age who have adequate CD4 T-cell reconstitution (>350 CD4 T cells per cubic millimeter) after more than 6 months of ART — need to be reconsidered. Despite the inclusion of participants with more than 2 years of ART and high CD4 T-cell counts (median count in participants >5 years of age, 720 per cubic millimeter), continued prophylaxis with co-trimoxazole led to sustained reductions in hospitalization for a range of infections, in areas where malaria is not endemic as well as in areas where it is endemic, with no evidence of variation across ages and with consistent benefits with respect to secondary end points. Continued co-trimoxazole prophylaxis had an acceptable safety profile and was not associated with poor adherence to ART.

These findings argue strongly for long-term co-trimoxazole prophylaxis in conjunction with ART in children and adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa, until further evidence is available to guide decisions about cessation of prophylaxis. Whether the benefits of co-trimoxazole will wane over the long term is unknown, but given the persistent risk we observed, co-trimoxazole will probably continue to provide a benefit after 2 years. Although an increase in the use of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis carries the risk of increased bacterial resistance in locations where co-trimoxazole is still used for first-line treatment, resistance rates are already high,1,4,7 and infections occurring in our study participants who had stopped receiving prophylaxis were often treated with broad-spectrum antibiotic agents, such as ceftriaxone. Longterm operational research would usefully address both these issues. Achieving widespread benefits from co-trimoxazole for children in ART programs will require additional training of health workers and improved methods of drug-use forecasting and procurement of co-trimoxazole at health facilities to prevent depletion of stocks.40

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the U.K. Medical Research Council and the U.K. Department for International Development. ViiV Healthcare and GlaxoSmithKline donated first-line drugs for the Antiretroviral Research for Watoto (ARROW) trial and provided funding for virologic assays.

We thank the participants, caregivers, and staff from all the centers participating in the ARROW trial.

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org

References

- 1.Anglaret X, Chêne G, Attia A, et al. Early chemoprophylaxis with trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole for HIV-1-infected adults in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire: a randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;353:1463–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)07399-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Badri M, Ehrlich R, Wood R, Maartens G. Initiating co-trimoxazole prophylaxis in HIV-infected patients in Africa: an evaluation of the provisional WHO/UNAIDS recommendations. AIDS. 2001;15:1143–8. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200106150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grimwade K, Sturm AW, Nunn AJ, Mbatha D, Zungu D, Gilks CF. Effectiveness of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis on mortality in adults with tuberculosis in rural South Africa. AIDS. 2005;19:163–8. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200501280-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mermin J, Lule J, Ekwaru JP, et al. Effect of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis on morbidity, mortality, CD4-cell count, and viral load in HIV infection in rural Uganda. Lancet. 2004;364:1428–34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17225-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nunn AJ, Mwaba P, Chintu C, Mwinga A, Darbyshire JH, Zumla A. Role of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis in reducing mortality in HIV infected adults being treated for tuberculosis: randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2008;337:a257. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiktor SZ, Sassan-Morokro M, Grant AD, et al. Efficacy of trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole prophylaxis to decrease morbidity and mortality in HIV-1-infected patients with tuberculosis in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1999;353:1469–75. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)03465-0. Erratum, Lancet 1999;353:2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chintu C, Bhat GJ, Walker AS, et al. Co-trimoxazole as prophylaxis against opportunistic infections in HIV-infected Zambian children (CHAP): a double-blind randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1865–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17442-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mulenga V, Ford D, Walker AS, et al. Effect of co-trimoxazole on causes of death, hospital admissions and antibiotic use in HIV-infected children. AIDS. 2007;21:77–84. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280114ed7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sutcliffe CG, van Dijk JH, Bolton C, Persaud D, Moss WJ. Effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected children in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:477–89. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70180-4. Erratum, Lancet Infect Dis 2009;9:736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in infants and children: towards universal access — recommendations for a public health approach. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2010. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/paediatric/infants2010/en/index.html [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guidelines on co-trimoxazole prophylaxis for HIV-related infections among children, adolescents and adults in resource-limited settings: recommendations for a public health approach. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2006. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/plhiv/ctx/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 12.Urschel S, Ramos J, Mellado M, et al. Withdrawal of Pneumocystis jirovecii prophylaxis in HIV-infected children under highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2005;19:2103–8. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000194795.20928.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nachman S, Gona P, Dankner W, et al. The rate of serious bacterial infections among HIV-infected children with immune reconstitution who have discontinued opportunistic infection prophylaxis. Pediatrics. 2005;115(4):e488–e494. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suthar AB, Granich R, Mermin J, Van Rie A. Effect of co-trimoxazole on mortality in HIV-infected adults on antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90:128C–138C. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.093260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walker AS, Ford D, Gilks CF, et al. Daily co-trimoxazole prophylaxis in severely immunosuppressed HIV-infected adults in Africa started on combination antiretroviral therapy: an observational analysis of the DART cohort. Lancet. 2010;375:1278–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60057-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ARROW Trial Team Routine versus clinically driven laboratory monitoring and first-line antiretroviral therapy strategies in African children with HIV (ARROW): a 5-year open-label randomised factorial trial. Lancet. 2013;381:1391–403. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62198-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.ICH tripartite guideline: clinical safety data management: definitions and standards for expedited reporting; International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use; 1994; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.WHO case definitions of HIV for surveillance and revised clinical staging and immunological classification of HIV-related disease in adults and children. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2006. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/hivstaging/en/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peto R, Pike MC, Armitage P, et al. Design and analysis of randomized clinical trials requiring prolonged observation of each patient. I. Introduction and design. Br J Cancer. 1976;34:585–612. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1976.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Royston P, Parmar MK. Flexible parametric proportional-hazards and proportional-odds models for censored survival data, with application to prognostic modelling and estimation of treatment effects. Stat Med. 2002;21:2175–97. doi: 10.1002/sim.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gasasira AF, Kamya MR, Ochong EO, et al. Effect of trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole on the risk of malaria in HIV-infected Ugandan children living in an area of widespread antifolate resistance. Malar J. 2010;9:177. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamya MR, Gasasira AF, Achan J, et al. Effects of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and insecticide-treated bednets on malaria among HIV-infected Ugandan children. AIDS. 2007;21:2059–66. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282ef6da1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mermin J, Ekwaru JP, Liechty CA, et al. Effect of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis, antiretroviral therapy, and insecticide-treated bednets on the frequency of malaria in HIV-1-infected adults in Uganda: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2006;367:1256–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68541-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campbell JD, Moore D, Degerman R, et al. HIV-infected Ugandan adults taking antiretroviral therapy with CD4 counts >200 cells/μL who discontinue co-trimoxazole prophylaxis have increased risk of malaria and diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:1204–11. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamer DH, Gill CJ. Balancing individual benefit against public health risk: the impact of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis in HIV-infected patients on antimicrobial resistance. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79:299–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamel MJ, Greene C, Chiller T, et al. Does co-trimoxazole prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV-associated opportunistic infections select for resistant pathogens in Kenyan adults? Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79:320–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malamba SS, Mermin J, Reingold A, et al. Effect of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis taken by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected persons on the selection of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine-resistant malaria parasites among HIV-uninfected household members. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:375–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thera MA, Sehdev PS, Coulibaly D, et al. Impact of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis on falciparum malaria infection and disease. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1823–9. doi: 10.1086/498249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. 2nd ed. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2010. http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/9789241547925/en/index.html [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anglaret X, Minga A, Gabillard D, et al. AIDS and non-AIDS morbidity and mortality across the spectrum of CD4 cell counts in HIV-infected adults before starting antiretroviral therapy in Cote d’Ivoire. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:714–23. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anglaret X, Toure S, Ouassa T, Dabis F, N’Dri-Yoman T. Thresholds of CD4 cells for initiating trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis in west Africa. AIDS. 2000;14:2628–9. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200011100-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corbett EL, Churchyard GJ, Charalambos S, et al. Morbidity and mortality in South African gold miners: impact of untreated disease due to human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1251–8. doi: 10.1086/339540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gilks CF, Ojoo SA, Ojoo JC, et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease in a cohort of predominantly HIV-1 infected female sex-workers in Nairobi, Kenya. Lancet. 1996;347:718–23. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forgacs P, Wengenack NL, Hall L, Zimmerman SK, Silverman ML, Roberts GD. Tuberculosis and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:4789–93. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01658-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chintu C, Mudenda V, Lucas S, et al. Lung diseases at necropsy in African children dying from respiratory illnesses: a descriptive necropsy study. Lancet. 2002;360:985–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11082-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gibb DM, Newberry A, Klein N, de Rossi A, Grosch-Woerner I, Babiker A. Immune repopulation after HAART in previously untreated HIV-1-infected children. Lancet. 2000;355:1331–2. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02117-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prendergast A, Walker AS, Mulenga V, Chintu C, Gibb DM. Improved growth and anemia in HIV-infected African children taking co-trimoxazole prophylaxis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:953–6. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gsponer T, Weigel R, Davies MA, et al. Variability of growth in children starting antiretroviral treatment in southern Africa. Pediatrics. 2012;130(4):e966–e977. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kreuzer KA, Rockstroh JK, Jelkmann W, Theisen A, Spengler U, Sauerbruch T. Inadequate erythropoietin response to anaemia in HIV patients: relationship to serum levels of tumour necrosis factoralpha, interleukin-6 and their soluble receptors. Br J Haematol. 1997;96:235–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.d01-2031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Date AA, Vitoria M, Granich R, Banda M, Fox MY, Gilks C. Implementation of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis and isoniazid preventive therapy for people living with HIV. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:253–9. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.066522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.