Abstract

Background

The Practitioners Engaged in Applied Research and Learning (PEARL) Network conducted a three-armed randomized clinical study to determine the comparative effectiveness of three treatments for hypersensitive noncarious cervical lesions (NCCLs): use of a potassium nitrate dentifrice for treatment of hypersensitivity, placement of a resin-based composite restoration and placement of a sealant.

Methods

Seventeen trained practitioner-investigators (P-Is) in the PEARL Network enrolled participants (N = 304) with hypersensitive posterior NCCLs who met enrollment criteria. Participants were assigned to treatments randomly. Evaluations were conducted at baseline and at one, three and six months thereafter. Primary outcomes were the reduction or elimination of hypersensitivity as measured clinically and by means of patient-reported outcomes.

Results

Lesion depth and pretreatment sensitivity (mean, 5.3 on a 0- to 10-point scale) were balanced across treatments, as was sleep bruxism (present in 42.2 percent of participants). The six-month participant recall rate was 99 percent. Treatments significantly reduced mean sensitivity (P < .01), with the sealant and restoration groups displaying a significantly higher reduction (P < .01) than did the dentifrice group. The dentifrice group’s mean (standard deviation) sensitivity at six months was 2.1 (2.1); those of the sealant and restoration groups were 1.0 (1.6) and 0.8 (1.4), respectively. Patient-reported sensitivity (to cold being most pronounced) paralleled clinical measurements at each evaluation.

Conclusions

Sealing and restoration treatments were effective overall in reducing NCCL hypersensitivity. The potassium nitrate dentifrice reduced sensitivity with increasing effectiveness through six months but not to the degree offered by the other treatments.

Practical Implications

Sealant or restoration placement is an effective method of immediately reducing NCCL sensitivity. Although a potassium nitrate dentifrice did reduce sensitivity slowly across six months, at no time was the reduction commensurate with that of sealants or restorations.

Keywords: Noncarious cervical lesion, bruxism, root sensitivity, resin-based composite, dental sealant, dentin-bonding agents, dentifrices, premolar, molar, restorative dentistry, operative dentistry

Finding effective methods other than restoration to treat hypersensitive noncarious cervical lesions (NCCLs) remains a problem. Like other dentists, practitioner-investigators (P-Is) in the Practitioners Engaged in Applied Research and Learning (PEARL) Network were eager to find alternatives to restoration of these hypersensitive lesions but had little guidance as to what is effective.1 In 2007, the PEARL Network executive committee, on the basis of a vote by the P-Is, directed the Network’s management team to develop and implement a study comparing the use of a chemoactive potassium nitrate dentifrice, application of a sealant or restoration with resin-based composite (RBC) in treatment of NCCLs. The New York University–based PEARL Network, New York City, includes The EMMES Corporation, Rockville, Md., which is the Network’s data coordinating center, and is a practice-based research network (PBRN) that through March 2013 was supported by a seven-year grant from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NI-DCR). The PEARL PBRN was described in a recent article2 and is in the process of becoming self-sustaining.

BACKGROUND

Tooth hypersensitivity is defined as pain caused by a nonnoxious stimulus. Teeth with exposed dentin or gingival recession are subject to dentin hypersensitivity. Tooth hypersensitivity can occur owing to abrasion, erosion or attrition of the enamel surface, which exposes the underlying dentin, or to gingival recession, which exposes the root surface. Such exposed surfaces near the gingival crest are referred to as “NCCLs.” Hypersensitivity generally is ascribed to fluid flow in open dentin tubules exposed by lesion progression.3–6

The authors of a comprehensive 2011 review regarding the etiology and prevalence of NCCLs pointed out the multifactorial causes of these lesions, including occlusion (abfraction) as a contributing factor.7 This review, when extended to consider restorative strategies, led the authors to suggest RBC restoration of these lesions on the basis of the results of studies one year or more in duration.8

Results from a 1998 study of dentists’ diagnosis and treatment of NCCLs indicated that the majority treated NCCLs via restoration,9 confirming earlier findings by Bader and colleagues.10 Guidelines published by the American Academy of Operative Dentistry in 2003 suggest a more conservative approach.11 Much of the clinical research regarding NCCLs in the last few years has concentrated on bonding agents and type of RBC used in the restoration.12–16 The factors affecting bonding to cervical dentin also have been reviewed.17 Other reviews of the etiology and management of NCCLs appeared in 2011.18,19

Investigators in an extensive 1994 review of the etiology of NCCLs discussed the multifactorial causes of these lesions,20 and several subsequent reviews21–23 supported its contentions. Bader and colleagues1 established these causes of NCCLs in a case-control study. Prevalence and risk factors reported in China in 201124 and previously in Trinidad25 are in line with findings in the United States and Europe. Although a review of articles published before 2005 showed little evidence that occlusion causes NCCLs,26 occlusion more recently was implicated as an important factor in several reviews.27,28 Results from the most recent comprehensive review of clinical studies suggests that this relationship still is in question,29 and proponents of abfraction noted the multifactorial etiology for NCCLs as the basis for a substantial proportion of these lesions.30

The most comprehensive clinical study of NCCLs is that of Lussi and Schaffner,31 who examined 204 participants in two age groups (26–30 and 46–50 years). At six years after evaluation, each of 55 participants was reexamined by the treating dentist by using the same indexes. NCCL defects were more pronounced in the older group at each recall. Lesions exhibited a distinct progression, and multiple regression analysis revealed that the progression of wedge-shaped lesions positively correlated with frequency of toothbrushing and age. Hyper- sensitivity remained the same as these lesions progressed. Lesion development and progression also has been followed in a dental student population.28,32 Sleep bruxism appears to be related to NCCLs.33 In a German study of participants (mean [standard deviation {SD}] age 28.4 [4.9] years) without and with sleep bruxism, the prevalence of NCCLs was 12.1 percent and 39.7 percent, respectively.34 In the sleep bruxism group, 62.1 percent of study participants and 36.4 percent of control participants reported hypersensitivity. This suggests that hypersensitive NCCLs are present in approximately 35 to 40 percent of all participants with these lesions, particularly among those with sleep bruxism. In general, NCCLs increase in prevalence with age, and NCCL hypersensitivity is a problem for many participants.

The effectiveness of conservative methods for the reduction of hypersensitivity, such as coatings or precipitating agents, is greatly reduced after four to 13 weeks of treatment.35,36 Investigators in a double-masked, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial compared methods for occluding dentin tubules.37 Positive treatment effects (P < .05) were present for all test treatments at four weeks and were not different from one another. Results from another study of the use of oxalic acid applied before a dentin-bonding agent (DBA) adhesive showed a significantly higher reduction in sensitivity compared with use of the DBA alone.38 Missing from these studies were comparisons with a chemoactive dentifrice and with restoration, as well as longer-term outcomes (six months or more). The authors of the oxalic acid application study38 noted that their results were contaminated by a strong placebo effect from a water rinse. The same strong placebo effect also was noted in a controlled study of a fluoride- containing mouthrinse for the reduction of dentin hypersensitivity.39

The PEARL Network executive management team designed a study to address PEARL P-Is’ concern regarding effective treatments for NCCLs. We believe this study is the first randomized controlled study at the investigator level to be conducted in a dental PBRN. Our research hypothesis was that restoration with RBC is significantly more effective in reducing or eliminating NCCL hypersensitivity, as measured clinically and by means of patient-reported outcome, than is the use of a potassium nitrate–containing dentifrice or sealant application.

METHODS

Study design

The study was a three-armed randomized clinical effectiveness study in which 17 PEARL P-Is enrolled patients as participants in the evaluation of NCCL treatments. Power analysis indicated that this three-armed study required recruitment of 100 participants per arm, thus allowing for a 20 percent dropout rate. This being a randomized clinical effectiveness study, training and calibration of PEARL P-Is and their staff were required. Using programs on DVDs and on PEARL’s website, we trained P-Is in the identification of lesions, minimum lesion depth measurements, hypersensitivity calibration and measurement, sleep bruxism evaluation, lesion impression techniques and treatment procedures. P-Is attended a learning session to standardize the air-blast method of assessing hypersensitivity. This required use of an anemometer (EC-30, Extech Instruments, Nashua, N.H.; no longer in production) to determine the distance from the tooth at which to position the air syringe for an air velocity of 4 to 5 meters per second. Participants at baseline and at each recall visit rated their hypersensitivity by using an 11-point (0–10) Numeric Pain Assessment Scale40 (NPAS) and completed questionnaires relating to stimuli that caused hypersensitivity and how hypersensitivity affected their quality of life. In addition, P-Is asked participants about their pain medication usage at each recall.

P-Is in this study were limited to those who had been engaged in at least one PEARL study previously and so already were experienced in administering participant surveys regarding hypersensitivity and quality of life. The New York University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved this study.

After enrollment, each eligible participant was assigned to one of three treatments. Assignments were randomized by computer by means of a 1:1:1 randomization among the three arms, with blocking within practice by using random block sizes. Figure 1 shows the timing of procedures and measurements.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of noncarious cervical lesion randomized clinical effectiveness trial.

Participant and tooth inclusion criteria

We required that participants have a premolar or first molar with an NCCL and indicate a hypersensitivity score of 3 or higher on the NPAS with standardized air-blast stimulation, with no other tooth in the same quadrant exhibiting hypersensitivity (which we defined as a score of 2 or higher as indicated by the participant on the NPAS). If the patient had a tooth in more than one quadrant that met these criteria, then the P-I selected the quadrant containing the tooth with the highest hypersensitivity reading. If the sensitivities were the same, the P-I selected the quadrant with the deepest lesion. If the sensitivities and depth were the same, the P-I selected the quadrant with the more convenient restorative access. We required that the selected tooth meet the following criteria: an NCCL depth of at least 1 millimeter, as measured by placing a periodontal probe into the deepest part of the cervical lesion; no mesial, distal or buccal restorations (to avoid confounding hypersensitivity); and a mobility of less than 1 mm when manipulated between blunt instruments. We required that participants agree to follow the study protocol, be willing to return for all evaluation appointments, comprehend and sign the written consent form, and be 18 years or older.

Participant and tooth exclusion criteria

We excluded participants who had a medical condition that could interfere with reliable pain reporting; were using a medication that could interfere with reliable pain reporting, such as an antidepressant; had used an analgesic medication (narcotic, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, acetaminophen, salicylic acid) within 24 hours before treatment; had used a desensitizing dentifrice within the preceding four weeks; had received an antihypersensitivity treatment (varnish or precipitating solution) of the identified tooth within the preceding four weeks; or were undergoing active orthodontic treatment. We also excluded hypersensitive teeth that had carious lesions, buccal vertical cracks in enamel, evidence of irreversible pulpitis (pain lasting more than five seconds after stimulation), full crowns, partial denture clasps on the facial surface, evidence of inflamed gingival tissue and bleeding on probing in the sextant being considered for treatment as part of the study.

Study treatments

The three study treatments were the use of dentifrice, sealant or restoration.

Dentifrice

Participants received masked tubes of dentifrice (containing 5 percent potassium nitrate and 0.2 percent sodium fluoride) for the study period, instructions for use and a soft-bristled toothbrush. Investigators measured the weight of each tube assigned with a digital scale provided to each P-I office (EC-11, Acculab, Danvers, Mass.) and recorded it to the nearest 0.1 gram at baseline and at each recall.

Sealant

Lesion treatment consisted of pumice cleaning, rinsing and light-drying, followed by application of a one-step self-etch DBA (Clearfil S3 Bond, Kuraray, Okayama, Japan), drying, curing and then brush application of a hydrophobic liner (Clearfil Liner Bond 2 Protect Liner F, Kuraray). The DBA and final resin layer each were light cured with a calibrated light source checked for output (minimum of 400 milliwatts per square centimeter as measured with a radiometer supplied to each P-I office [Demetron LED Radiometer, Kerr, Orange, Calif.]). We selected the DBA with sealant/liner on the basis of the findings of previous studies.36,41–44

Restoration

Lesion treatment entailed pumice cleaning, rinsing and drying, followed by DBA (Clearfil S3 Bond) application, curing with a calibrated light source, placement of flowable composite resin (Premise Flowable, Kerr) by means of hand instruments and contouring, curing and finishing of the restoration. We did not verify adherence to the manufacturer- recommended curing time (10-second minimum) for the restoration and sealant groups.

Study baseline data

We included the following as baseline data.

Hypersensitivity measurement

The P-I determined hypersensitivity by administering a one-second air blast (calibrated for an airflow of 4–5 m/second) parallel to the occlusal plane from the buccal aspect at the occlusal gingival height of the lesion.42,45 The P-I protected adjacent teeth with fingers or cotton rolls. The participant indicated on a 0- to 10-point NPAS40 the intensity of pain. We included in the study only teeth with NPAS scores of 3 or greater. Only a single tooth per patient qualified for the study, and we ensured that there was no more than one tooth with hypersensitivity in the same quadrant. For the purpose of this study, we defined hypersensitivity in a nonindex tooth as a value of 2 or greater as indicated by the participant on the NPAS.

Clinical evaluation for evidence of sleep bruxism

We based this evaluation on American Academy of Sleep Medicine33 criteria. On participant enrollment, the P-I inspected the participant’s dentition for evidence of tooth wear to at least the magnitude of dentin exposure. He or she also inspected the test tooth for wear and any facets greater than 1 mm in diameter and observed the participant for hypertrophy of masseter muscle(s) on clenching. In addition, he or she queried the participant as to awareness—the participant’s own or a partner’s—of tooth grinding while sleeping. We considered the presence of any one of these signs, singly or in combination, evidence of sleep bruxism.

Patient-reported outcomes

We measured patient outcomes by means of tooth hypersensitivity and quality-of-life surveys (modifications of standard PEARL surveys46). Included in the baseline evaluation were questions related to whether the patient could be classified as having sleep bruxism or was being treated for bruxism.34

Cervical impression

The P-I made a buccal surface impression of the study tooth in light-body polyvinylsiloxane impression material. A preliminary impression was made in the light-body material alone (to remove surface debris) and discarded. This process was followed immediately by the making of the final impression. P-Is sent all final impressions to the Department of Biomaterials and Biomimetics at New York University for analysis; there, the impressions were poured in epoxy to make replicas of the involved tooth surface. These lesion replicas were prepared and imaged by using scanning electron microscopy (S-3500N SEM, Hitachi, Tokyo) for ranking of dentin tubule visibility and occlusion via image analysis.5,47–49 Technical staff members, masked as to treatment arm and sensitivity scores, ranked dentin tubule visibility as follows: 1, tubules not visible; 2, tubules visible but covered with smear layer; 3, tubules visible and scattered; and 4, tubules visible (many) and organized. The technical staff members also determined changes in lesion size via measurement, at baseline and at six months, of coated replicas in a stereomicroscope equipped with a charge-coupled device camera and image measurement software (Zeiss Apotome [Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, N.Y.]) and imaging software (Image Pro Plus [Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, Md.]).

P-Is recalled participants at one, three and six months for hypersensitivity measurement, cervical impression and completion of hypersensitivity assessment, as well as quality-of-life surveys.

Statistical analysis

The primary objective of this study was to compare among three treatment groups the reduction of hypersensitivity of study teeth by means of both measurement and patient-reported outcomes at six months. Where not otherwise specified, the patient-reported score represents the maximum score reported across all stimuli. For both clinically measured sensitivity and patient-reported sensitivity, we computed change scores as the baseline hypersensitivity score minus the six-month hypersensitivity score. Given that the change scores from baseline to six months were nonnormal, we used a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test to assess differences among the three treatments. We performed pairwise tests by using the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test. We defined appreciable hypersensitivity (AH) as a score of 3 or higher on any stimuli. We used Kruskal-Wallis and c2 tests for continuous and categorical data analyses, respectively, as presented in Table 1. We made no adjustments for multiple comparisons.

TABLE 1.

Summary of participants’ baseline and laboratory characteristics, according to treatment assignment (intention to treat).

| BASELINE AND LABORATORY CHARACTERISTIC | TREATMENT

|

P VALUE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dentifrice | Restoration | Sealant | ||

|

| ||||

| Evidence of Sleep Bruxism, No. (%) | 41 (40.2) | 40 (40.4) | 47 (46.1) | .63 |

|

| ||||

| Air Velocity (Meters per Second) | .45 | |||

| Mean (standard deviation [SD]) (number) | 4.0 (0.3) (102) | 4.0 (0.3) (100) | 3.9 (0.3) (102) | |

| Median (minimum–maximum) | 4 (4–5) | 4 (4–5) | 4 (4–5) | |

|

| ||||

| Pretreatment Sensitivity to Air | .77 | |||

| Mean (SD) (number) | 5.3 (1.8) (102) | 5.4 (1.9) (100) | 5.3 (1.9) (102) | |

| Median (minimum–maximum) | 5 (3–10) | 5 (3–10) | 5 (3–10) | |

|

| ||||

| Pretreatment Longest Mesial Dimension of Lesion (Millimeters) | .95 | |||

| Mean (SD) (number) | 3.9 (1.3) (96) | 3.9 (1.2) (96) | 4.0 (1.2) (99) | |

| Median (minimum–maximum) | 4 (1–9) | 4 (2–8) | 4 (1–8) | |

|

| ||||

| Pretreatment Lesion Height (mm) | .40 | |||

| Mean (SD) (number) | 2.0 (0.9) (96) | 2.0 (0.9) (96) | 1.9 (1.0) (99) | |

| Median (minimum–maximum) | 2 (1–5) | 2 (0–5) | 2 (1–7) | |

|

| ||||

| Pretreatment Dentin Tubule Visibility Rank, No. (%)* | .88 | |||

| 1 = Tubules not visible | 50 (51.0) | 52 (53.1) | 57 (56.4) | |

| 2 = Tubules visible with smear layer | 20 (20.4) | 17 (17.3) | 15 (14.9) | |

| 3 = Tubules visible and scattered | 18 (18.4) | 15 (15.3) | 15 (14.9) | |

| 4 = Tubules visible (many) and organized | 10 (10.2) | 14 (14.3) | 14 (13.9) | |

Data obtained with a scanning electron microscope.

Monitoring

Because this was a randomized controlled standard-of-care study, in addition to its New York University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board review, the study was monitored by an NIDCR-appointed data safety and monitoring board. This board reviewed and approved the protocol before study implementation and then met with us every six months to review formal reports of study progress, adherence to protocol, adverse events and the statistical analysis being used.

RESULTS

Seventeen PEARL P-Is enrolled 304 participants in the study, ranging from two participants at one site to 40 or more at each of two sites, with 12 of the 17 P-Is enrolling 10 or more participants each. There was no misrandomization of participants, and the number of completed posttreatment visits was high: 98.7 percent (300 of 304) at one month, 99.0 percent (294 of 297) at three months and 99.0 percent (293 of 296) at six months, indicating the strong recall capabilities found in these PBRN practices. Five patients withdrew from the study after enrollment, and three were lost to follow-up. At the six-month recall, P-Is evaluated 101 participants in the dentifrice group, 94 in the sealant group and 93 in the restoration group. There were five instances of replacement treatments—two sealants and three restorations lost retention—and there was a return of sensitivity in one participant in each of these arms.

The baseline clinically measured sensitivities of the three groups were equivalent (Table 1), with an overall mean of 5.3 in each as measured by means of a calibrated air blast with a median velocity of 4 m/second (range, 4–5). In addition, the patient-reported sensitivities to the range of stimuli were equivalent across the groups, with the highest sensitivities reported to cold foods or beverages. The mean (SD) patient age was 45.9 (10.4) years, and the male-to-female distribution was 33.6 percent to 66.4 percent, with equivalent distributions across groups. There was evidence of sleep bruxism in 42.2 percent of participants, and those with bruxism were well distributed across the three arms. Comparison of the baseline NCCL sensitivity level of those with sleep bruxism to those without (not shown) does not indicate a difference. Most teeth in the study were premolars (88 percent). There was no difference in the percentage of NCCL-affected teeth with bruxism when we compared molars with premolars, nor when we compared maxillary teeth with mandibular teeth.

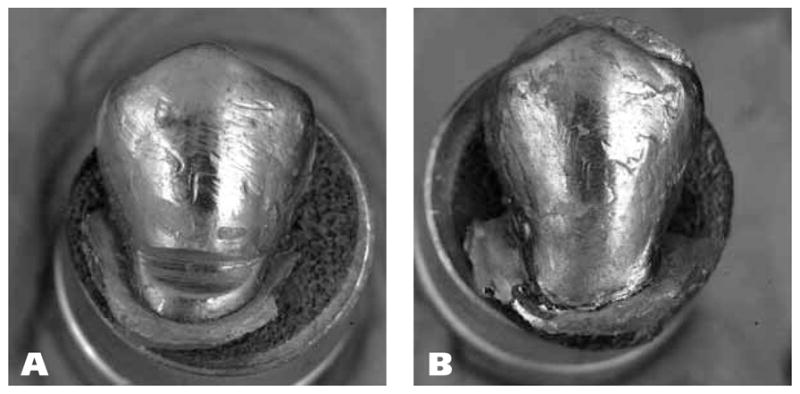

The baseline length, height and depth of the lesions were equivalent across the groups, as were the rankings of dentin tubule visibility and presence of open tubules (Table 1; Figure 2, page 502). The air velocity used to measure test tooth hypersensitivity was within the 4- to 5-m/second limits, as was the output of the curing lights used for the sealant and restoration treatment arms.

Figure 2.

Stereomicroscopic macrographs (magnification x3.5) of metal-coated replicas of a noncarious cervical lesion (A) at baseline and (B) after restoration at six-month recall. Note the overextension of the flowable composite, here occlusally and distally, a condition sometimes observed in such tooth-colored restorations.

The pretreatment hypersensitivity score was higher than 5.0 across all treatments, and this score was significantly reduced for participants in the sealant and restoration groups, with an immediate posttreatment mean of 1.5 for each. Figure 3 (page 503) shows the clinically measured hypersensitivity at baseline and each recall for the three treatment groups. The hypersensitivity means for the dentifrice, sealant and restoration groups at months 1, 2 and 6 were 2.2, 1.6 and 1.3, respectively. Looking at this primary outcome across treatment groups, we find that the sealant and restoration groups at each point showed a more pronounced and significantly higher (P < .01) reduction in sensitivity, whether measured or patient reported, than did the dentifrice group (Figures 3 and 4, page 503). Although sensitivity reduction was slightly lower among participants in the restoration group, there was no significant difference in sensitivity reduction compared with that in participants in the sealant group. We are showing only the patient-reported sensitivity for cold, which had the highest levels of sensitivity; but this relationship also held for the other stimuli (hot, sweet, chewing and clenching). Note that the potassium nitrate dentifrice had a notable effect in reducing sensitivity, one that increased at each recall through six months. The dentifrice was significantly less effective in reducing sensitivity, however, compared with results in the other treatment arms at all recalls.

Figure 3.

Mean score on 0- to 10-point numeric pain assessment scale of participant sensitivity in response to a dentist-applied calibrated air blast of one second. Bars show standard deviations.

Figure 4.

Mean score of participant-reported sensitivity to cold beverages or food on the treated tooth at baseline and at each recall. Bars show standard deviations.

Table 2 summarizes the change in clinically measured and patient-reported sensitivity between baseline and six months according to assigned treatment. These results indicate the correspondence between the clinically measured and the patient-reported sensitivity outcomes. When comparing change in sensitivity according to treatment, we found no significant difference between sealants and RBC.

TABLE 2.

Change in sensitivity after six months according to comparison of treatment assignment (intention to treat).

| HYPERSENSITIVITY | ASSIGNED TREATMENT | MEAN (STANDARD DEVIATION) (NUMBER) | MEDIAN (MINIMUM- MAXIMUM) | Z STATISTIC | P VALUE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinically Measured | Dentifrice | 3.2 (2.2) (101) | 3 (−2 to 8) | 3.7517 | < .01 |

| Restoration | 4.6 (2.3) (93) | 4 (−1 to 10) | |||

| Restoration | 4.6 (2.3) (93) | 4 (−1 to 10) | 1.4606 | .14 | |

| Sealant | 4.1 (1.9) (94) | 4 (0–10) | |||

| Dentifrice | 3.2 (2.2) (101) | 3 (−2 to 8) | 2.6037 | < .01 | |

| Sealant | 4.1 (1.9) (94) | 4 (0–10) | |||

| Patient Reported | Dentifrice | 3.5 (2.3) (101) | 3 (−2 to 10) | 2.6222 | < .01 |

| Restoration | 4.4 (2.5) (93) | 4 (−2 to 10) | |||

| Restoration | 4.4 (2.5) (93) | 4 (−2 to 10) | 0.0804 | .94 | |

| Sealant | 4.4 (2.4) (94) | 4 (−3 to 10) | |||

| Dentifrice | 3.5 (2.3) (101) | 3 (−2 to 10) | 2.6119 | < .01 | |

| Sealant | 4.4 (2.4) (94) | 4 (−3 to 10) |

In our previous work46,50 we defined AH as values of 3 or higher on the 0- to 10-point NPAS, and this was the basis for our having included in this study participants who had clinically measured AH. Figure 5 (page 503) indicates the numbers of patients in each group who had AH after treatment. Note that the patient-reported results agree with the clinically measured outcomes for the comparative effectiveness of the treatments.

Figure 5.

Percentage of participants reporting appreciable sensitivity (a score ≥ 3) on the treated tooth at baseline and at each recall. Bars show standard deviations.

The secondary outcomes of this study—patient-reported outcomes related to quality of life, laboratory evaluations of lesion impression replicas to investigate the relationship between open dentin tubules and measured hypersensitivity, and change in lesion size—will be reported elsewhere.

DISCUSSION

Our findings indicate that, across the limited time course of this study, there was no statistically significant difference between clinician-stimulated or patient-reported sensitivity reduction in NCCLs between the restoration and sealant treatments. Whether these findings will hold for longer periods remains to be determined. The low loss rates for both groups by six months (3 percent or less) and continuing reduction in sensitivity across time suggest that these treatments generally are successful; but the range in sensitivity scores was 0 to 8 for the sealant group and 0 to 7 for the restoration group at six months, indicating that the treatment was not effective for some participants. In laboratory evaluations of replicas, the sealant did not appear to be wearing at the six-month recall. Considering the comparative cost and time involved, the use of the one-step self-etching bonding agent followed by coating with a hydrophilic sealant appears effective as compared with restoration across the limited time of this study. Ideally, the active-treatment participants in our study would have been recalled at two years and the groups compared again, but funding did not permit this.

We found the potassium nitrate dentifrice to reduce sensitivity significantly at each recall. Results from a previous study of a 5 percent potassium nitrate–containing dentifrice in reducing sensitivity indicated continued effectiveness across four- and 12-week recalls.51 Such a continuing effect was noted in 2011 in a six-month study in which investigators used a dentifrice containing calcium sodium phosphosilicate with and without an in-office application of a paste formulation.52 Investigators have published reviews of recent desensitizing formulations and their associated clinical studies.53,54 Only a few studies of desensitizing dentifrices extend beyond eight weeks’ duration, and most are completed at 12 weeks as per label requirements.55,56 It remains to be determined whether the continued reduction in sensitivity we observed in the dentifrice group would continue across time and become equivalent to that of the other treatments. It also remains to be determined from our data if there is a relationship between open dentin tubules observed in clinical replicas and the effectiveness of the dentifrice. The inclusion criterion of NCCLs at least 1 mm in depth defines a lesion that may differ from the traditional initial sensitive depression in dentin, which may be site and depth dependent. The deeper lesions in our study may initiate defensive pulpal reactions that self-limit hypersensitivity and may be a confounding variable in long-term dentifrice studies.

Strengths of the study

The strengths of this study are many: calibration of clinicians’ technique, the baseline balance found among treatment groups, the high recall rate, use of a calibrated air blast to check sensitivity, the adherence of dentists to random assignment of participant treatment and their following of placement protocols, and the correspondence between dentists’ clinical findings and participant-reported outcomes.

Technique calibration of the P-Is in this study involved the use of study groups to work out procedures and agree on calibrations. We then used this information to produce videos (accessible on DVD and the Web) covering lesion depth measurement; calibration and use of the air syringe stimulus; impression technique; bonding agent, sealant and RBC placement; weighing of dentifrice tubes at recall; sleep bruxism diagnosis; and, finally, equipoise. We determined P-Is’ viewing via associated quiz results.

Randomization proved effective in having a baseline clinically measured sensitivity of just higher than 5 on the 0- to 10-point scale. (Recall that we required patients to have an air-blast sensitivity of at least 3 to be enrolled in the study.) Sleep bruxism was distributed approximately equally across the treatment arms and was in the range of 40 to 46 percent, being highest in the sealant group. This value is higher than anticipated but is similar to that reported in a European study of NCCLs in which 39.7 percent of all participants exhibited sleep bruxism.34 In that study, however, among participants with sensitive NCCLs, 62.1 percent exhibited sleep bruxism. The average age of our participants was more than 20 years older than that in the Ommerborn and colleagues study,34 and we selected patients who had sensitive NCCLs. In our study, the baseline NCCL sensitivity level of participants with sleep bruxism did not differ from that of participants without the condition. Presence of sleep bruxism did not affect the treatment outcomes compared with those in participants who did not have this condition. Recently, investigators noted a relationship between bruxism and occlusal habits and the presence of NCCLs, in which NCCLs were found predominantly on maxillary premolars (32 percent) and were associated positively with tooth clenching.57 In our study, premolars were the teeth most often found with sensitive NCCLs, but they were distributed approximately equally between the mandible and the maxilla.

PEARL Network P-Is were highly effective in adherence to the treatment protocols and recall evaluations. There was no misrandomization of participants, and the completed posttreatment visits varied from 98.7 percent at one month to 99.0 percent at both three- and six-month recalls. This high recall rate suggests that PBRN studies have the potential to be cost effective. In addition, the P-Is in the study kept excellent records overall. Monitoring of site activities by PEARL clinical research associates, a distinguishing characteristic of the Network aimed at ensuring data integrity, provided review of 70.4 percent of data forms and noted a protocol discrepancy rate of merely 0.36 percent. All these discrepancies were resolved, with deviations from the protocol (n = 22) being related primarily to participants’ failing to return within the recall window.

In sensitivity studies that involve the use of an air blast as the stimulus, the air velocity and time of application should be calibrated, and we believe this is the first study that has provided a method of calibration across practices. We used a one-second application, calibrated by means of the clinician’s use of an anemometer to determine the distance from the syringe tip to the anemometer vane face required to achieve a velocity of 4 to 5 m/second. We chose the air velocity on the basis of trials with a number of air syringes and tips to allow a reasonable distance between the tip and the tooth surface (estimated range, 15–60 mm). A number of P-Is reported their surprise at the variation among air syringes (between tips and between chairs), and they indicated their appreciation for the importance of calibration at each visit.

The 17 P-Is used a range of halogen and light-emitting diode lights for curing the bonding agent, the sealant and the flowable RBC, and as a consequence determination of a minimum light output was important at each participant treatment. There was 100 percent verification that light output met the minimum requirement (400 mW/cm2) as measured with the radiometer, with the median being 600 mW/cm2 and the maximum 1,000 mW/cm2. We did not verify adherence to the stated curing times, and this may have led to some variability.

The correspondence between dentist-measured results and patient-reported outcomes at baseline and each recall supports the overall findings of the study. Cold was the stimulus with the highest participant-reported mean score at baseline and each recall, followed by sweet, hot, chewing and clenching. There were no significant differences between stimulus sensitivity scores across treatment groups at any time, suggesting uniformity in treatment effectiveness and group composition.

Possible concerns relative to the study

Some clinicians might question whether our restoration outcomes might differ if we employed a highly filled, high-elastic-modulus RBC. We used a low-elastic-modulus flowable RBC in this study because of its convenience of application. However, the RBC’s elastic modulus may not be a factor in the success of cervical restorations as compared with the adhesive used. Investigators in a recently completed 13-year study compared two three-step etch-and-rinse adhesives and found an adhesive used with a high-elastic-modulus RBC to have a failure rate of only 12 percent, whereas another adhesive had a 26 percent failure rate when used with hybrid RBC restorations and a 22 percent failure rate when used with a low-modulus microfill.58 In another cervical lesion study involving the use of a single adhesive, investigators found no difference in clinical performance between hybrid RBC and flowable RBC restorations.12

There has been a criticism that failure to add phosphoric acid etching of the enamel margin with a one-step bonding system such as we used may lead to loss of retention.14 This was supported by results from a study in which the authors noted a reduced NCCL RBC retention rate of 78.8 percent at 24 months with a one-step DBA.59 However, researchers in another study comparing etched with unetched enamel margins in NCCL restoration with a one-step DBA found 100 percent retention in both groups at two years.60 Also in NCCL restoration, comparison of one- and two-step self-etching DBAs from the same manufacturer resulted in 85 percent and 91 percent retention rates, respectively, at 24 months,61 whereas investigators in another study found 24-month retention rates with two- and three-step DBAs of 91 percent and 97 percent, respectively.15 A clinical comparison of the one-step DBA used in our study, Clearfil S3, with the two-step Clearfil SE in NCCL RBC restorations showed equivalent retention rates of 81 to 84 percent at 24 months.16 Although we cannot project our retention rate to 24 months, the 3 percent loss of retention for the flowable RBC restorations in our study by three months, with no further loss at six months, suggests at least a comparable outcome.

Alternative methods to treat NCCL hypersensitivity have been suggested, including application of oxalic acid or oxalates to the dentin before DBA application. Results from a 2011 clinical study showed a significantly higher reduction in sensitivity with application of an oxalate before bonding.38 However, authors of a critical review of the literature62 and a critical summary63 concluded that oxalates have not been proven effective in treating dentin hypersensitivity. Varnish also has been evaluated in reducing post–periodontal surgery root sensitivity.64 In a recent study of varnish formulas to control hypersensitivity at 90 days, there was a significant reduction in sensitivity on anterior as opposed to posterior teeth.65 Note that our study was confined to posterior teeth. Glass ionomer and, more recently, resin-modified glass ionomer have been recommended for the treatment of NCCLs.66 Results from one five-year study indicated the effectiveness of a resin-modified glass ionomer in treating sensitive NCCLs.67 Studies to compare the effectiveness of these modalities with dentifrice, sealant and RBC restoration remain to be completed.

Limitations of the study

A limitation in our study is related to the P-Is and their study population. PEARL P-Is are a motivated group of dentists willing to undergo training and to donate a portion of the cost of the study in their practices (although NIDCR did provide some offsetting stipends per participant enrolled), so the results may not be generally applicable. Also the participants enrolled are from a predominantly suburban setting, and these findings might differ in other populations.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings demonstrate that over the six months of this study, both the sealant and the restoration treatment proved equally effective for most participants in reducing hypersensitivity in NCCLs. The relative ease of application of the sealant compared with that of the restoration might save considerable time in treating NCCLs. Although the use of dentifrice was not as effective, the reduction in hypersensitivity associated with it appeared to increase with each recall. These findings strongly suggest the need for a long-term (three- to five-year) study to determine the most effective outcomes between these treatment options.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The research described in this article was supported by grant U01- DE016755 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md.

The authors are indebted to the work of the Practitioners Engaged in Applied Research and Learning Network practitioner-investigators who contributed their own time and that of their staff to this study. They also would like to note the contribution of Juliann Wu, MS, of The EMMES Corporation, Rockville, Md., to aspects of the statistical analysis.

Opinions are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health.

ABBREVIATION KEY

- AH

Appreciable hypersensitivity

- DBA

Dentin-bonding agent

- HS

Hypersensitivity

- NCCL

Noncarious cervical lesion

- NIDCR

National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research

- NPAS

Numeric Pain Assessment Scale

- PBRN

Practice-based research network

- PEARL

Practitioners Engaged in Applied Research and Learning

- P-I

Practitioner-investigator

- RBC

Resin-based composite

Footnotes

Disclosure. None of the authors reported any disclosures.

Contributor Information

Dr. Analia Veitz-Keenan, Dentist in private practice in New York City; a clinical associate professor and the academic director, Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology, Radiology and Medicine, College of Dentistry, New York University, New York City; and a practitioner-investigator in the Practitioners Engaged in Applied Research and Learning Network, New York City.

Dr. Julie Ann Barna, Dentist in private practice in Lewisburg, Pa., and a practitioner-investigator in the Practitioners Engaged in Applied Research and Learning Network, New York City.

Dr. Brad Strober, Dentist in private practice in Edison, N.J., and a practitioner-investigator in the Practitioners Engaged in Applied Research and Learning Network, New York City.

Dr. Abigail G. Matthews, Biostatistician, The EMMES Corporation, Rockville, Md.

Mr. Damon Collie, Project manager, The EMMES Corporation, Rockville, Md.

Mr. Donald Vena, Statistician, The EMMES Corporation, Rockville, Md.

Dr. Frederick A. Curro, Clinical professor, Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology, Radiology and Medicine, College of Dentistry, New York University, New York City; and the director of recruitment, retention and operations, Practitioners Engaged in Applied Research and Learning Network, New York City.

Dr. Van P. Thompson, Director of protocol development and training, Practitioners Engaged in Applied Research and Learning Network, and a professor and the chairperson, Biomaterials and Biomimetics, New York University College of Dentistry, New York City. He now is a professor, Biomaterials, Biomimetics and Biophotonics Research Group, The Dental Institute, King’s College London.

References

- 1.Bader JD, McClure F, Scurria MS, Shugars DA, Heymann HO. Case-control study of non-carious cervical lesions. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1996;24(4):286–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1996.tb00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curro FA, Vena D, Naftolin F, Terracio L, Thompson VP. The PBRN initiative: transforming new technologies to improve patient care. J Dent Res. 2012;91(7 suppl):12S–20S. doi: 10.1177/0022034512447948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cuenin MF, Scheidt MJ, O’Neal RB, et al. An in vivo study of dentin sensitivity: the relation of dentin sensitivity and the patency of dentin tubules. J Periodontol. 1991;62(11):668–673. doi: 10.1902/jop.1991.62.11.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshiyama M, Ozaki K, Ebisu S. Morphological characterization of hypersensitive human radicular dentin and the effect of a light-curing resin liner on tubular occlusion. Proc Finn Dent Soc. 1992;88(suppl 1):337–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ianzano JA, Gwinnett AJ, Westbay G. Polymeric sealing of dentinal tubules to control sensitivity: preliminary observations. Periodontal Clin Investig. 1993;15(1):13–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rimondini L, Baroni C, Carrassi A. Ultrastructure of hypersensitive and non-sensitive dentine: a study on replica models. J Clin Periodontol. 1995;22(12):899–902. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1995.tb01792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pecie R, Krejci I, Garcia-Godoy F, Bortolotto T. Noncarious cervical lesions: a clinical concept based on the literature review, part 1—prevention. Am J Dent. 2011;24(1):49–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pecie R, Krejci I, García-Godoy F, Bortolotto T. Noncarious cervical lesions (NCCL): a clinical concept based on the literature review, part 2—restoration. Am J Dent. 2011;24(3):183–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lyttle HA, Sidhu N, Smyth B. A study of the classification and treatment of noncarious cervical lesions by general practitioners. J Prosthet Dent. 1998;79(3):342–346. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(98)70248-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bader JD, Levitch LC, Shugars DA, Heymann HO, McClure F. How dentists classified and treated non-carious cervical lesions. JADA. 1993;124(5):46–54. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1993.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Academy of Operative Dentistry. Non-carious cervical lesions: recommendations for clinical practice. Oper Dent. 2003;28(2):109–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kubo S, Yokota H, Yokota H, Hayashi Y. Three-year clinical evaluation of a flowable and a hybrid resin composite in non-carious cervical lesions (published online ahead of print Oct. 17, 2009) J Dent. 2010;38(3):191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loguercio AD, Raffo J, Bassani F, et al. 24-month clinical evaluation in non-carious cervical lesions of a two-step etch-and-rinse adhesive applied using a rubbing motion (published online ahead of print April 20, 2010) Clin Oral Investig. 2011;15(4):589–596. doi: 10.1007/s00784-010-0408-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fron H, Vergnes JN, Moussally C, et al. Effectiveness of a new one-step self-etch adhesive in the restoration of non-carious cervical lesions: 2-year results of a randomized controlled practice-based study (published online ahead of print Nov. 30, 2010) Dent Mater. 2011;27(3):304–312. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reis A, Mânica D, Ferneda F, et al. A 24-month randomized clinical trial of a two- and three-step etch-and-rinse technique. Am J Dent. 2010;23(4):231–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brackett MG, Dib A, Franco G, Estrada BE, Brackett WW. Two-year clinical performance of Clearfil SE and Clearfil S3 in restoration of unabraded non-carious class V lesions. Oper Dent. 2010;35(3):273–278. doi: 10.2341/09-266-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perdigão J. Dentin bonding-variables related to the clinical situation and the substrate treatment (published online ahead of print Dec. 14, 2009) Dent Mater. 2010;26(2):e24–e37. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2009.11.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chu CH, Lam A, Lo EC. Dentin hypersensitivity and its management. Gen Dent. 2011;59(2):115–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terry DA. Cervical dentin hypersensitivity: etiology, diagnosis, and management. Dent Today. 2011;30(4):61–62. 64, 68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levitch LC, Bader JD, Shugars DA, Heymann HO. Non-carious cervical lesions. J Dent. 1994;22(4):195–207. doi: 10.1016/0300-5712(94)90107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burke FJ, Whitehead SA, McCaughey AD. Contemporary concepts in the pathogenesis of the Class V non-carious lesion. Dent Update. 1995;22(1):28–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osborne-Smith KL, Burke FJ, Wilson NH. The aetiology of the non-carious cervical lesion. Int Dent J. 1999;49(3):139–143. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-595x.1999.tb00898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tyas MJ. The Class V lesion: aetiology and restoration. Aust Dent J. 1995;40(3):167–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1995.tb05631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang H, Du MQ, Huang W, Peng B, Bian Z, Tai BJ. The prevalence of and risk factors for non-carious cervical lesions in adults in Hubei Province, China. Community Dent Health. 2011;28(1):22–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith WA, Marchan S, Rafeek RN. The prevalence and severity of non-carious cervical lesions in a group of patients attending a university hospital in Trinidad (published online ahead of print July 11, 2007) J Oral Rehabil. 2008;35(2):128–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2007.01763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bartlett DW, Shah P. A critical review of non-carious cervical (wear) lesions and the role of abfraction, erosion, and abrasion. J Dent Res. 2006;85(4):306–312. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ceruti P, Menicucci G, Mariani GD, Pittoni D, Gassino G. Non carious cervical lesions: a review. Minerva Stomatol. 2006;55(1–2):43–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Telles D, Pegoraro LF, Pereira JC. Incidence of noncarious cervical lesions and their relation to the presence of wear facets. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2006;18(4):178–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.2006.00015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Senna P, Del Bel Cury A, Rösing C. Non-carious cervical lesions and occlusion: a systematic review of clinical studies (published online ahead of print March 21, 2012) J Oral Rehabil. 2012;39(6):450–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2012.02290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grippo JO, Simring M, Coleman TA. Abfraction, abrasion, biocorrosion, and the enigma of noncarious cervical lesions: a 20-year perspective (published online ahead of print Nov. 17, 2011) J Esthet Restor Dent. 2012;24(1):10–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.2011.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lussi A, Schaffner M. Progression of and risk factors for dental erosion and wedge-shaped defects over a 6-year period. Caries Res. 2000;34(2):182–187. doi: 10.1159/000016587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Telles D, Pegoraro LF, Pereira JC. Prevalence of noncarious cervical lesions and their relation to occlusal aspects: a clinical study. J Esthet Dent. 2000;12(1):10–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.2000.tb00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The international classification of sleep disorders, second ed.: diagnostic and coding manual. Westchester, Ill: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ommerborn MA, Schneider C, Giraki M, et al. In vivo evaluation of noncarious cervical lesions in sleep bruxism subjects. J Prosthet Dent. 2007;98(2):150–158. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(07)60048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gillam DG, Newman HN, Davies EH, Bulman JS, Troullos ES, Curro FA. Clinical evaluation of ferric oxalate in relieving dentine hypersensitivity (published correction appears in J Oral Rehabil 2004;31[8]:827) J Oral Rehabil. 2004;31(3):245–250. doi: 10.1046/j.0305-182X.2003.01230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duran I, Sengun A. The long-term effectiveness of five current desensitizing products on cervical dentine sensitivity. J Oral Rehabil. 2004;31(4):351–356. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2003.01241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pamir T, Dalgar H, Onal B. Clinical evaluation of three desensitizing agents in relieving dentin hypersensitivity. Oper Dent. 2007;32(6):544–548. doi: 10.2341/07-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barrientos C, Xaus G, Leighton C, Martin J, Gordan VV, Moncada G. Oxalic acid under adhesive restorations as a means to reduce dentin sensitivity: a four-month clinical trial. Oper Dent. 2011;36(2):126–132. doi: 10.2341/09-364-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yates RJ, Newcombe RG, Addy M. Dentine hypersensitivity: a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled study of the efficacy of a fluoride-sensitive teeth mouthrinse. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31(10):885–889. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Swarm R, Abernethy AP, Anghelescu DL, et al. Adult cancer pain: clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8(9):1046–1086. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ide M, Morel AD, Wilson RF, Ashley FP. The rôle of a dentine-bonding agent in reducing cervical dentine sensitivity. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25(4):286–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prati C, Cervellati F, Sanasi V, Montebugnoli L. Treatment of cervical dentin hypersensitivity with resin adhesives: 4-week evaluation. Am J Dent. 2001;14(6):378–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trowbridge HO, Silver DR. A review of current approaches to in-office management of tooth hypersensitivity. Dent Clin North Am. 1990;34(3):561–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kakaboura A, Rahiotis C, Thomaidis S, Doukoudakis S. Clinical effectiveness of two agents on the treatment of tooth cervical hypersensitivity. Am J Dent. 2005;18(4):291–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zantner C, Popescu O, Martus P, Kielbassa AM. Randomized clinical study on the efficacy of a new lacquer for dentine hypersensitivity. Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed. 2006;116(12):1232–1237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berkowitz GS, Horowitz AJ, Curro FA, et al. Postoperative hypersensitivity in class I resin-based composite restorations in general practice: interim results. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2009;30(6):356–358. 360, 362–363. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Absi EG, Addy M, Adams D. Dentine hypersensitivity: a study of the patency of dentinal tubules in sensitive and non-sensitive cervical dentine. J Clin Periodontol. 1987;14(5):280–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1987.tb01533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Absi EG, Addy M, Adams D. Dentine hypersensitivity: uptake of toothpastes onto dentine and effects of brushing, washing and dietary acid—SEM in vitro study. J Oral Rehabil. 1995;22(3):175–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.1995.tb01561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kerns DG, Scheidt MJ, Pashley DH, Horner JA, Strong SL, Van Dyke TE. Dentinal tubule occlusion and root hypersensitivity. J Periodontol. 1991;62(7):421–428. doi: 10.1902/jop.1991.62.7.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lehmann M, Veitz-Keenan A, Matthews AG, et al. Dentin caries activity in early occlusal lesions selected to receive operative treatment: findings from the Practitioners Engaged in Applied Research and Learning (PEARL) Network. JADA. 2012;143(4):377–385. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2012.0180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wara-aswapati N, Krongnawakul D, Jiraviboon D, Adulyanon S, Karimbux N, Pitiphat W. The effect of a new toothpaste containing potassium nitrate and triclosan on gingival health, plaque formation and dentine hypersensitivity. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32(1):53–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Patsouri A, Mavrogiannea A, Pepelassi E, Gaintantzopoulou M, Kakaboura A. Clinical effectiveness of a desensitizing system on dentin hypersensitivity in periodontitis patients. Am J Dent. 2011;24(2):85–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cummins D. Advances in the clinical management of dentin hypersensitivity: a review of recent evidence for the efficacy of dentifrices in providing instant and lasting relief. J Clin Dent. 2011;22(4):100–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gendreau L, Barlow AP, Mason SC. Overview of the clinical evidence for the use of NovaMin in providing relief from the pain of dentin hypersensitivity. J Clin Dent. 2011;22(3):90–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sharma N, Roy S, Kakar A, Greenspan DC, Scott R. A clinical study comparing oral formulations containing 7.5% calcium sodium phosphosilicate (NovaMin), 5% potassium nitrate, and 0. 4% stannous fluoride for the management of dentin hypersensitivity. J Clin Dent. 2010;21(3):88–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schiff T, Delgado E, Zhang YP, Cummins D, DeVizio W, Mateo LR. Clinical evaluation of the efficacy of an in-office desensitizing paste containing 8% arginine and calcium carbonate in providing instant and lasting relief of dentin hypersensitivity. Am J Dent. 2009;22(special issue A):8A–15A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brandini DA, Pedrini D, Panzarini SR, Benete IM, Trevisan CL. Clinical evaluation of the association of noncarious cervical lesions, parafunctional habits, and TMD diagnosis. Quintessence Int. 2012;43(3):255–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peumans M, De Munck J, Van Landuyt KL, Poitevin A, Lambrechts P, Van Meerbeek B. A 13-year clinical evaluation of two three-step etch-and-rinse adhesives in non-carious class-V lesions (published online ahead of print Oct. 8, 2010) Clin Oral Investig. 2012;16(1):129–137. doi: 10.1007/s00784-010-0481-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Santiago SL, Passos VF, Vieira AH, Navarro MF, Lauris JR, Franco EB. Two-year clinical evaluation of resinous restorative systems in non-carious cervical lesions. Braz Dental J. 2010;21(3):229–234. doi: 10.1590/s0103-64402010000300010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abdalla AI, El Sayed HY. Clinical evaluation of a self-etch adhesive in non-carious cervical lesions. Am J Dent. 2008;21(5):327–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Loguercio AD, Mânica D, Ferneda F, et al. A randomized clinical evaluation of a one- and two-step self-etch adhesive over 24 months. Oper Dent. 2010;35(3):265–272. doi: 10.2341/09-241-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cunha-Cruz J, Stout JR, Heaton LJ, Wataha JC. Northwest PRECEDENT. Dentin hypersensitivity and oxalates: a systematic review (published online ahead of print Dec. 29, 2010) J Dent Res. 2011;90(3):304–310. doi: 10.1177/0022034510389179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Balevi B. Oxalates may not be effective in treating dentin hypersensitivity. JADA. 2012;143(6):614–615. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2012.0240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vaitkeviciene I, Paipaliene P, Zekonis G. Clinical effectiveness of dentin sealer in treating dental root sensitivity following periodontal surgery. Medicina (Kaunas) 2006;42(3):195–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Drebenstedt S, Zapf A, Rödig T, Mausberg RF, Ziebolz D. Efficacy of two different CHX-containing desensitizers: a controlled double-blind study (published online ahead of print Dec. 14, 2011) Oper Dent. 2012;37(2):161–171. doi: 10.2341/10-231-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tantbirojn D, Poolthong S, Leevailoj C, Srisawasdi S, Hodges JS, Randall RC. Clinical evaluation of a resin-modified glass-ionomer liner for cervical dentin hypersensitivity treatment. Am J Dent. 2006;19(1):56–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Loguercio AD, Reis A, Barbosa AN, Roulet JF. Five-year double-blind randomized clinical evaluation of a resin-modified glass ionomer and a polyacid-modified resin in noncarious cervical lesions. J Adhes Dent. 2003;5(4):323–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.