Abstract

The Sweet syndrome, or acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, is rare and has characteristic clinical, physical, and pathologic findings: abrupt onset of pyrexia, elevated neutrophil count, tender erythematous skin lesions, and a diffuse infiltrate of mature neutrophils in the reticular dermis with edema in the papillary dermis. The Sweet syndrome can be further classified based on the clinical setting: classical, malignancy-associated, and drug-induced. Diagnosis can alert the clinician to the presence of an underlying malignancy or the recurrence of a malignancy. The most commonly associated malignancy is acute myelogenous leukemia. We present three cases of Sweet syndrome associated with hematopoietic neoplasms.

The Sweet syndrome, also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, is a rare condition characterized by an abrupt onset of pyrexia, an elevated neutrophil count, tender erythematous skin lesions, and a diffuse infiltrate of mature neutrophils in the reticular dermis with edema in the papillary dermis. We present three patients with the Sweet syndrome associated with hematopoietic neoplasms.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

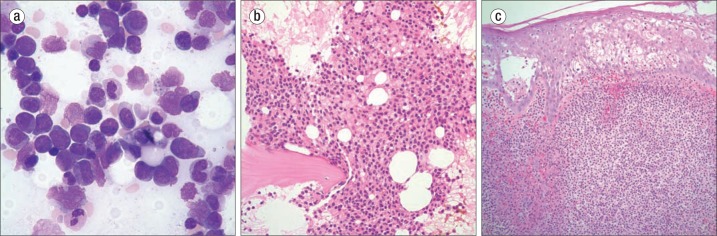

A 52-year-old man developed a nonpruritic erythematous rash over both upper extremities, the neck, and upper back accompanied by a fever of 102° F. Table 1 provides the laboratory values. Anemia, thrombocytopenia, and the presence of blasts in the peripheral blood prompted a bone marrow examination that revealed 45% blasts and trilineage dysplasia. A diagnosis of acute myelogenous leukemia was made, possibly arising from a myelodysplastic disorder (Figure 1a). Cytogenetics revealed a deletion of 5q that supported the diagnosis. A biopsy of one of the erythematous nodules was considered to be consistent with Sweet syndrome. These resolved after steroid treatment. Concomitantly his leukemia was treated with cytarabine and daunorubicin, and remission was obtained. His postremission therapy was high-dose cytosine arabinoside, and he is currently being monitored.

Table 1.

Clinical findings in the three patients

| Characteristic | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 52 | 65 | 74 |

| Gender | Male | Male | Female |

| Location of rash | B, E, N | B, E, F | E |

| Duration of rash (years) | 0.2 | 2 | 4 |

| Body temperature (°F) | 102° | 102.2° | 98.0° |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.2 | 9.5 | 9.5 |

| Hematocrit | 28.4% | 28.9% | 28.5% |

| White blood cell count (×109/L) | 35.4 | 1.2 | 9.4–>19.2 |

| Neutrophils | 92% | 54% | 76%–>83% |

| Lymphocytes | 4% | 46% | 16% |

| Blasts | 2% | 0% | 0% |

| Platelet count (×109/L) | 70 | 113 | 300 |

| Bone marrow blasts | 45% | 0% | <1% |

| Dermal biopsy | Sweet syndrome | Sweet syndrome | Sweet syndrome |

| Associated malignancy | AML | Hairy cell leukemia | MGUS, CLL/SLL |

B indicates back; E, extremity; F, face; N, neck; AML, acute myelogenous leukemia; MGUS, monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance; CLL/SLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma.

Figure 1.

(a) Bone marrow aspirate in case 1 showing acute myelogenous leukemia with dysplastic changes. Wright stain ×970. (b) Bone marrow biopsy in case 2 showing an infiltrate of hairy cell leukemia. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), ×400. (c) Skin biopsy in case 3 showing a neutrophilic infiltrate consistent with a diagnosis of Sweet syndrome. H&E ×400.

Case 2

A 65-year-old man had a 2-year history of a skin rash that was suspected to be scabies, as he is a veterinarian's assistant. Scrapings, however, were negative. He was treated with ivermectin and the rash disappeared but reoccurred. Recently the rash worsened and involved the face, upper back, and extremities. The patient also had a fever of 102°F with flulike symptoms. The rash was described as edematous and erythematous with 1 to 2 cm plaques and was nonpruritic. Other important findings included pancytopenia (Table 1). A skin biopsy was obtained and interpreted as Sweet syndrome. A significant physical finding was splenomegaly. A bone marrow biopsy revealed hairy cell leukemia (Figure 1b). The patient was started on a 7-day course of cladribine 0.1 mg/kg per day by continuous intravenous infusion. The skin lesions were treated with corticosteroids (prednisone) and resolved over a 7-day period. A repeat bone marrow biopsy 8 weeks later revealed no evidence of leukemia.

Case 3

A 74-year-old woman was admitted in 2009 with several erythematous lesions on the dorsum of the left hand and bilateral lower extremities. The lesions were suspicious for pyoderma gangrenosum, and she was treated with mupirocin and prednisone. In April 2011 she was admitted with painful dark bullae on the dorsum of her fingers and bilateral upper and lower extremities. Table 1 lists her blood counts. A right thigh lesion was biopsied, and findings were consistent with Sweet syndrome. Intravenous steroids were initiated, and she was discharged on oral prednisone. In October 2012 she again developed erythematous lesions over her extremities. A shave biopsy of a toe lesion was considered to be a recurrence of Sweet syndrome (Figure 1c). The patient was again treated with steroids with resolution of the lesions.

A hematology/oncology consult was obtained, as neoplastic lesions are known to occur with the Sweet syndrome. Flow cytometry found a 5% population of clonal B cells that expressed CD5 and a 2% population of clonal plasma cells. Both populations of cells expressed kappa light chain. She subsequently was found to have a small 0.7 g/dL IgG monoclonal protein. At this time she is considered to have a monoclonal B cell lymphocytosis with the immunophenotype of chronic lymphocytic leukemia/lymphoma and a plasma cell dyscrasia that may represent monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance. She is being followed on a regular basis.

DISCUSSION

Sweet syndrome was originally described by Robert Douglas Sweet in 1964 (1). The syndrome is characterized by pyrexia, elevated neutrophil count, painful red papules or plaques, and an infiltrate of predominantly mature neutrophils diffusely distributed in the upper dermis. Sweet syndrome can be classified based upon the clinical setting in which it occurs: classical or idiopathic, malignancy-associated, and drug-induced (2).

Sweet syndrome is believed to be a reactive phenomenon and should be considered a cutaneous marker of systemic disease (3). Careful systemic evaluation is indicated, especially when cutaneous lesions are severe or hematologic values are abnormal. Approximately 20% of cases are associated with malignancy, particularly hematologic malignancy (3–5). Moreover, an underlying condition such as streptococcal infection, inflammatory bowel disease, solid tumors, or pregnancy is found in up to 50% of cases of Sweet syndrome (6–8). Sweet syndrome may precede the hematologic diagnosis by months to years, so close evaluation of individuals in the idiopathic type is necessary.

There is now some evidence that treatment with hematopoietic growth factors can cause Sweet syndrome due to induction of stem cell proliferation, differentiation of neutrophils, and prolonged neutrophil survival (9, 10). Evidence supporting an immune phenomenon includes the dramatic response to steroids and similarities with hypersensitivity reactions like erythema nodosum and erythema multiforme (3). The use of steroids results in a dramatic response in the majority of patients with either idiopathic or malignancy-associated Sweet syndrome (3). Patients with hematologic malignancy–associated Sweet syndrome usually receive cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents and/or antimetabolic drugs for the treatment of their underlying disorder.

Systemic corticosteroids (prednisone) produce rapid improvement and are considered the “gold standard” for treatment of Sweet syndrome. The skin lesions usually clear within 3 to 9 days. Topical and/or intralesional corticosteroids may be effective as either monotherapy or adjuvant therapy. Oral potassium iodide or colchicine may induce rapid resolution (11). Individuals who have a potential systemic infection or in whom corticosteroids are contraindicated can use the above agents as first-line therapy. Other alternatives to corticosteroid treatment include dapsone, doxycycline, clofazimine, and cyclosporine (2). All of these agents influence neutrophil migration and function.

Corticosteroids were used for the skin lesions in our patients. In cases 1 and 2, chemotherapeutic agents were also used for the hematologic malignancy. The third patient is being monitored, as she has two clonal populations of cells (lymphocytes and plasma cells) that have not yet manifested into treatable diseases.

References

- 1.Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1964.tb14541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet's syndrome: a review of current treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3(2):117–131. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200203020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet's syndrome and malignancy. Am J Med. 1987;82(6):1220–1226. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spector JI, Zimbler H, Levine R, Ross JS, Valigorsky JM, Cole LM. Sweet's syndrome. Association with acute leukemia. JAMA. 1980;244(10):1131–1132. doi: 10.1001/jama.244.10.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klock JC, Oken RL. Febrile neutrophilic dermatosis in acute myelogenous leukemia. Cancer. 1976;37(2):922–927. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197602)37:2<922::aid-cncr2820370245>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen PR, Talpaz M, Kurzrock R. Malignancy-associated Sweet's syndrome: review of the world literature. J Clin Oncol. 1988;6(12):1887–1897. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1988.6.12.1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper PH, Innes DJ, Jr, Greer KE. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet's syndrome) and myeloproliferative disorders. Cancer. 1983;51(8):1518–1526. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19830415)51:8<1518::aid-cncr2820510827>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soppi E, Nousiainen T, Seppa A, Lahtinen R. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet's syndrome) in association with myelodysplastic syndromes: a report of three cases and a review of the literature. Br J Haematol. 1989;73(1):43–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1989.tb00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glaspy JA, Baldwin GC, Robertson PA, Souza L, Vincent M, Ambersley J, Golde DW. Therapy for neutropenia in hairy cell leukemia with recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109(10):789–795. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-109-10-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park JW, Mehrotra B, Barnett BO, Baron AD, Venook AP. The Sweet syndrome during therapy with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116(12 Pt 1):996–998. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-12-996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suehisa S, Tagami H, Inoue F, Matsumoto K, Yoshikuni K. Colchicine in the treatment of acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet's syndrome) Br J Dermatol. 1983;108(1):99–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1983.tb04584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]