Abstract

Objective

To describe what women of reproductive age who received primary care at a refugee health clinic were using for contraception upon arrival to the clinic, and to quantify the unmet contraceptive needs within that population.

Design

Retrospective chart review.

Setting

Crossroads Clinic in downtown Toronto, Ont.

Participants

Women of reproductive age (15 to 49 years) who first presented for care between December 1, 2011, and December 1, 2012. To be included, a woman had to have had 2 or more clinic visits or an annual health examination. Exclusion criteria for the contraception prevalence calculation were female sexual partner, menopause, hysterectomy, pregnancy, or trying to conceive.

Main outcome measures

Contraception use prevalence was measured, as was unmet contraceptive need, which was calculated using a modified version of the World Health Organization’s definition: the number of women with an unmet need was expressed as a percentage of women of reproductive age who were married or in a union, or who were sexually active.

Results

Overall, 52 women met the criteria for inclusion in the contraceptive prevalence calculation. Of these, 16 women (30.8%) did not use any form of contraception. Twelve women were pregnant at some point in the year and stated the pregnancy was unwanted or mistimed. An additional 14 women were not using contraception but had no intention of becoming pregnant within the next 2 years. There were no women with postpartum amenorrhea not using contraception and who had wanted to delay or prevent their previous pregnancy. In total, 97 women were married or in a union, or were sexually active. Unmet need was calculated as follows: (12 + 14 + 0)/97 = 26.8%.

Conclusion

There was a high unmet contraceptive need in the refugee population in our study. All women of reproductive age should be screened for contraceptive need when first seeking medical care in Canada.

Résumé

Objectif

Déterminer lesquelles parmi les femmes en âge de procréer qui reçoivent des soins primaires à une clinique de santé pour réfugiés utilisaient une méthode contraceptive à leur arrivée à la clinique et quantifier leur taux de besoins de contraception non satisfaits.

Type d’étude

Revue rétrospective de dossiers.

Contexte

La clinique Crossroads du centre-ville de Toronto, en Ontario.

Participantes

Des femmes en âge de procréer de 15 à 49 ans ayant consulté pour la première fois entre le 1er décembre 2011 et le 1er décembre 2012. Pour être incluse, une femme devait avoir visité la clinique au moins 2 fois ou y avoir eu un examen de santé annuel. Les critères d’exclusion suivants ont été utilisés pour le calcul de la prévalence de contraception : avoir une femme comme partenaire sexuelle, être ménopausée, avoir eu une hystérectomie, être enceinte ou chercher à le devenir.

Principaux paramètres à l’étude

La prévalence d’utilisation d’une méthode contraceptive; le taux de besoins de contraception non satisfaits, calculé à l’aide d’une version modifiée de la définition de l’Organisation mondiale de la Santé, c’est-à-dire en exprimant le nombre de femmes ayant des besoins non satisfaits en pourcentage des femmes en âge de procréer qui étaient mariées ou en union libre, ou qui étaient sexuellement actives.

Résultats

En tout, 52 femmes ont répondu aux critères d’inclusion pour le calcul de la prévalence de contraception. Parmi ces femmes, 16 (30,8 %) n’utilisaient aucune méthode contraceptive. À un moment ou l’autre de l’année, 12 femmes ont été enceintes et ont déclaré que leur grossesse n’était pas désirée ou survenait à un mauvais moment. Un autre groupe de 14 femmes n’utilisaient pas de contraception alors qu’elles n’avaient aucune intention de devenir enceintes au cours des 2 années suivantes. Les femmes en aménorrhée du postpartum à la suite d’une grossesse non désirée ou survenue à un moment inopportun utilisaient toutes une méthode contraceptive (nombre de ces femmes n’utilisant pas de méthode = 0). Au total, 97 femmes étaient mariées, en union libre ou étaient sexuellement actives. On s’est servi du nombre de femmes dans chacun de ces groupes pour calculer le taux de besoins non satisfaits: (12 + 14 + 0) ÷ 97 = 26,8 %.

Conclusion

Cette étude a permis de constater qu’il y a beaucoup de besoins de contraception non satisfaits chez les réfugiés. On devrait aborder le sujet de la contraception avec toutes les femmes en âge de procréer qui consultent pour la première fois au Canada.

Sexual and reproductive health are key aspects of every woman’s right to health.1 The achievement of universal access to reproductive care is specifically targeted within the United Nations’ fifth Millennium Development Goal.2 Five of the other Millennium Development Goals—eradicate extreme poverty and hunger, achieve universal primary education, promote gender equality and empower women, reduce child mortality, and ensure environmental sustainability—are also closely linked with reproductive health. Reproductive health problems are the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in women of childbearing age worldwide.3 Furthermore, maternal and newborn deaths result in global productivity losses of about $15 billion per year.3 The World Health Organization’s definition of reproductive health includes each person’s capability to reproduce and the freedom to decide if, when, and how to do so.4

Contraception plays an important role in reproductive health. The use of contraception can prevent unintended pregnancy, reduce abortion, increase opportunities to attain higher education, and stimulate economic growth.3,5–7 According to the United Nations Population Fund, 1 in 3 deaths in women of childbearing age can be prevented by family planning.8 There are currently 222 million women of reproductive age worldwide with unmet contraceptive needs.5 In some countries, more than half of women report that their last pregnancy was unintended.3

Numerous studies have shown that refugees (individuals who left their home countries to escape persecution) are a group particularly vulnerable to having unmet contraceptive needs. A Spanish cross-sectional study found that more than one-third of induced abortions occurred in immigrant women.9 Yugoslavian refugees in the United Kingdom presenting to a genitourinary clinic were more likely to report no contraceptive use and 1 or more previous pregnancy terminations compared with age-matched UK women.10 Numerous studies of undocumented migrants in Geneva, Switzerland, found lower rates of contraceptive use, higher rates of unintended pregnancies, and higher rates of induced abortions compared with women with legal residency.11–13 A population-based registry in the Netherlands found a pregnancy termination rate of 30.2 per 1000 women per year among refugees compared with a 16.7 per 1000 women per year rate among non-migrants.14

At the end of 2011, there were 15.2 million refugees worldwide.15 In that year, Canada accepted about 25 000 refugees, 38% of whom settled in Toronto, Ont.16,17 A report put out by Toronto Public Health identified sexual health services as an unmet need of newcomers to the city.18

There is no known fertility pattern among refugees. Some refugees increase fertility to replace deceased children or satisfy their desire to repopulate as they move to healthier and more stable environments.19 Others decrease fertility owing to uncertainty about the future, economic instability, or marital separation.

Currently, there are no data available in the literature as to what refugee women in Canada are using for contraception and what the unmet contraceptive needs are within this population. The purpose of this study was to describe what women of reproductive age receiving primary care at a refugee health clinic in downtown Toronto were using for contraception upon arrival to the clinic. Furthermore, the study aimed to quantify the unmet contraceptive needs within this population.

METHODS

In January 2013, research ethics approval was obtained from the Women’s College Hospital Research Ethics Board for a retrospective chart review. The study population was women of reproductive age (15 to 49 years) who first presented for a visit to the Crossroads Clinic between December 1, 2011, and December 1, 2012. The Crossroads Clinic is a refugee health clinic at Women’s College Hospital in Toronto with the mandate of providing comprehensive medical services to refugees for their first 2 years in the city.

The focus was on women receiving primary care at the clinic; therefore, one inclusion criterion was either 2 or more visits to the clinic (representing continuity of care) or an annual health examination at the clinic (representing comprehensiveness of care). We excluded women who did not have a need for contraception, namely those who had female partners, were postmenopausal, had had hysterectomies, were pregnant, or were trying to conceive. Because our research question focused on contraception upon arrival to the clinic, we used contraception data from each woman’s first visit during which sexual activity or contraception was discussed. If the contraception status of a sexually active woman was unclear from the chart review, the nurse practitioner who conducted the visit was consulted to see if she recalled the information.

A modified version of the World Health Organization’s definition of unmet needs for family planning was used to quantify the unmet needs in our population (Table 1).20 We broadened the definition to include women who were single and sexually active because these women were also at risk of unwanted pregnancy (Table 1).20 For calculation of unmet needs, data were used from the entire year as opposed to just the initial visit.

Table 1.

Unmet need definition

| WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION DEFINITION20 | MODIFIED DEFINITION |

|---|---|

| Calculation pertaining to women of reproductive age (15–49 y) | Calculation pertaining to women of reproductive age (15–49 y) |

Unmet need = (A + B + C)/No. of women married or in a union

|

Unmet need = (A + B + C)/No. women married or in a union, or sexually active

|

RESULTS

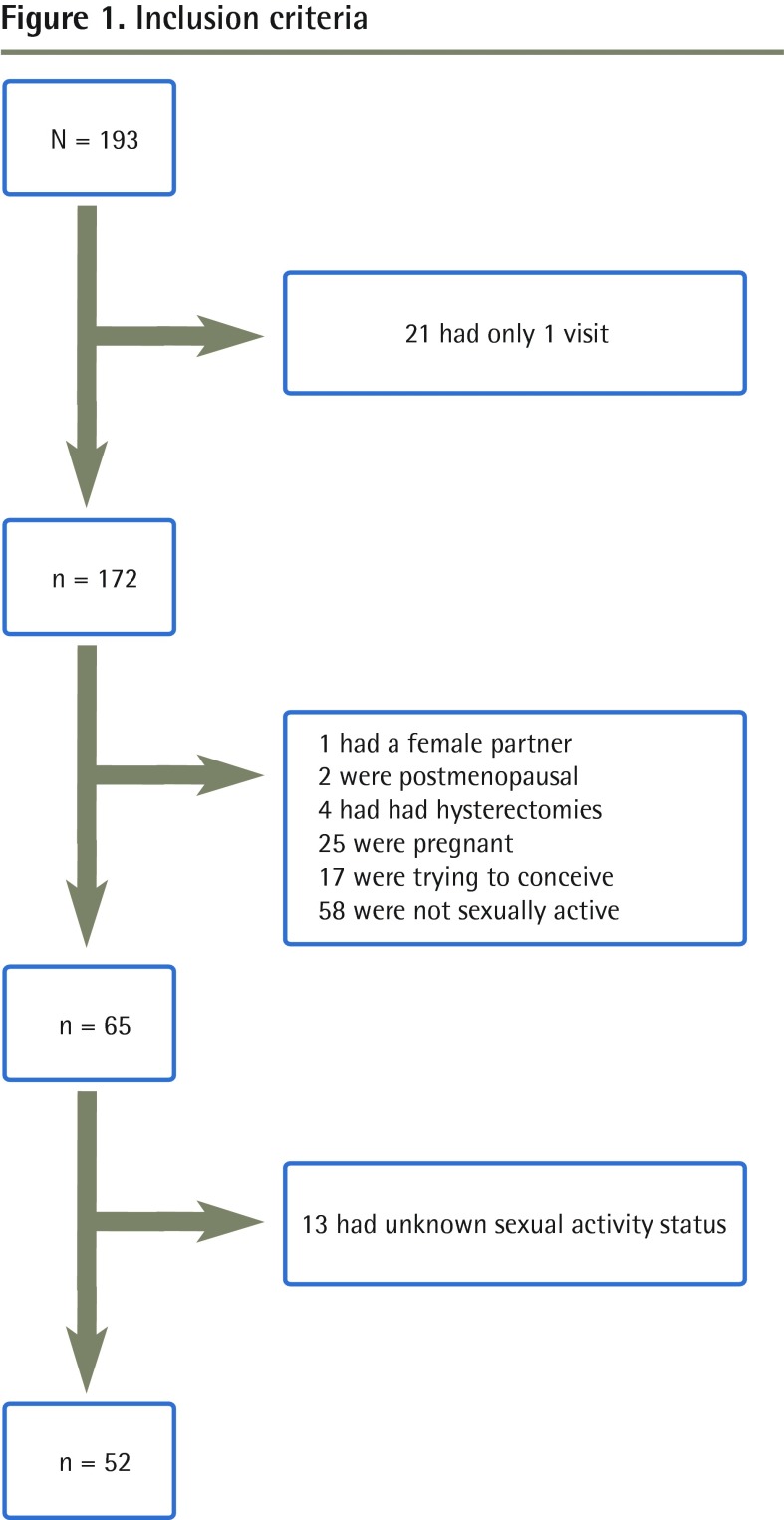

Contraceptive prevalence

A total of 193 women visited the Crossroads Clinic between December 1, 2011, and December 1, 2012, and out of those, 21 only had 1 visit. Out of the 172 who had more than 1 visit, 1 had only female partners, 2 were postmenopausal, 4 had had hysterectomies, 25 were pregnant, 17 were trying to conceive, and 58 were not sexually active. This left 65 women. Out of this group, sexual activity status was unclear for 13. We were then left with 52 women (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Inclusion criteria

Demographic characteristics of the women are summarized in Table 2. There was only 1 teenager in the sample. Otherwise, women were distributed fairly equally among the age groups, with a slightly higher proportion of women between the ages of 30 and 34 (30.8%). Most women in the sample were married (65.4%) or in a long-term relationship (21.2%). Most were born in Europe (63.5%). The remainder were born in Africa (13.5%), Asia (11.5%), and Latin and South America (11.5%). Most had had 1 or more previous pregnancies (88.5%).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics: N = 52.

| CHARACTERISTIC | VALUE, N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, y | |

| • 15–19 | 1 (1.9) |

| • 20–24 | 6 (11.5) |

| • 25–29 | 9 (17.3) |

| • 30–34 | 16 (30.8) |

| • 35–39 | 7 (13.5) |

| • 40–44 | 6 (11.5) |

| • 45–49 | 7 (13.5) |

| Relationship status | |

| • Single | 5 (9.6) |

| • Separated | 2 (3.8) |

| • Common law or partner | 11 (21.2) |

| • Married | 34 (65.4) |

| Region of birth | |

| • Africa | 7 (13.5) |

| • Asia | 6 (11.5) |

| • Europe | 33 (63.5) |

| • Latin or South America | 6 (11.5) |

| Gravidity | |

| • 0 | 4 (7.7) |

| • ≥ 1 | 46 (88.5) |

| • Unknown | 2 (3.8) |

| Education level | |

| • Some or completed primary | 13 (25.0) |

| • Some or completed secondary | 17 (32.7) |

| • Some or completed postsecondary | 20 (38.5) |

| • Unknown | 2 (3.8) |

Contraceptive methods are listed in Table 3. About one-third of the women reported not using any form of contraception (n = 16). Out of those using contraception, the most common method used was condoms (n = 12, 23.1%), followed by sterilization (n = 8, 15.4%) and intrauterine devices (n = 4, 7.7%).

Table 3.

Prevalence of contraceptive methods: N = 52.

| TYPE OF CONTRACEPTION | VALUE, N (%) |

|---|---|

| Condom | 12 (23.1) |

| Oral contraceptive | 0 (0.0) |

| Injection | 0 (0.0) |

| Intrauterine device | 4 (7.7) |

| Implant | 1 (1.9) |

| Sterilization | 8 (15.4) |

| Withdrawal | 2 (3.8) |

| Unknown | 9 (17.3) |

| None | 16 (30.8) |

Unmet contraceptive needs

The denominator used for the calculation of unmet need included all women with 2 or more clinic visits or an annual health examination that were either married or in a long-term union, or single and sexually active (Figure 2). Women who were postmenopausal or had undergone hysterectomies were excluded. The numerator included women not using contraception but having no intention of pregnancy within the next 2 years (A); women who were currently pregnant but the pregnancy was unwanted or mistimed (B); and women with postpartum amenorrhea not using contraception and who had wanted to delay or prevent their previous pregnancy (C).

Figure 2.

Topics discussed during meetings with faculty advisors: N = 89.

The calculation went as follows: A = 14, B = 12, C = 0. Unmet need = (14 + 12 + 0)/97 = 26.8%

DISCUSSION

We found that 30.8% of women did not use any form of contraception. This estimate is much higher than comparable Canadian data. The 2002 Canadian Contraception Study found that only 9% of sexually active reproductive-aged women not trying to conceive did not use any form of contraception.21 A 2006 Canadian cross-sectional survey found that 14.9% of sexually active reproductive-age women not trying to conceive did not use any form of contraception.22 Contraceptive prevalence might be lower in the refugee population because of a lack of access to contraception, lack of knowledge about how to use contraceptive methods, fear of side effects, or cultural or religious reasons.23,24 The only study we came across looking at prevalence of contraceptive practices in refugees was conducted in New Zealand between 1995 and 2000.25 In that study, half of the refugee women were not using contraception upon arrival. However, it is not directly comparable to our study because pregnancy status and sexual activity status were not addressed.

Contraceptive choices upon arrival to our clinic differed compared with Canadian data. We found condoms were the most popular contraceptive choice at 23.1%, followed by sterilization at 15.4% and intrauterine devices at 7.7%. None of the patients was using oral contraceptive pills (OCPs). The 2002 Canadian study found that OCPs were the most popular method of contraception at 32%, followed by sterilization at 22% and condoms at 21%.21 The 2006 Canadian study found condoms were most popular at 54.3%, followed by OCPs at 43.7% and sterilization at 13.4%.22

Global data from 2010, which were published in The Lancet in 2013 and came from nationally representative surveys of women aged 15 to 49 who were married or in a union, showed that worldwide contraceptive prevalence was 63.3%.26 In our study, if we assumed the women with unknown contraceptive status were using contraception, our prevalence would have been 69.2%. However, if we assumed the women in the unknown group were not using contraception, our contraceptive prevalence would only have been 51.9%, much lower than the worldwide prevalence.

There are some important differences between our study and the comparison studies just described. Both Canadian studies were cross-sectional surveys, whereas our study was a retrospective chart review. The cross-sectional studies might pick up on some information a chart review would miss because participants must all answer the same questions at a given point in time, whereas with a chart review, certain questions might not have been asked during clinic visits. Additionally, the cross-sectional studies provided answer options that participants could choose from, whereas in our study, participants had to come up with their own responses. Because of this we might have missed data on natural birth control methods (eg, withdrawal, periodic abstinence) because participants might not think natural methods would be included. Furthermore, in the cross-sectional studies, participants were able to select several contraceptive options, whereas in our study, each participant only endorsed 1 option. The global data in The Lancet study focused solely on women who were married or in a union, and our data focused on all sexually active women.

Limitations

First, there are a lot of unknown data in terms of sexual activity and contraception use. We took a conservative approach when completing calculations by not including those with unknown sexual activity in our contraception prevalence denominator and by assuming those with unknown contraception use did not have an unmet need. Second, language barriers exist, and women might not have been comfortable giving personal answers through interpreters. Third, many women attended clinic visits with their children and thus might not have had the opportunity to share contraception information. Fourth, the unmet need might have been overestimated in that women needing therapeutic abortions might have specifically been referred to our clinic to be connected with those services. Additionally, it might be difficult to generalize the data found; a much more substantial percentage of our sample consisted of Roma refugees from Hungary compared with other Canadian refugee clinics. Finally, sexual health needs change over time. By using only 1 point in time to gather contraception use data, valuable information might have been missed.

We found that the unmet contraceptive need in our sample was 26.8%. This is higher than the global estimation of unmet need reported in The Lancet article, which was only 12.3%.26 The unmet need in our study population was also much higher than the unmet need reported for Canada (8.0%). It is possible that unmet needs are higher in refugee populations owing to lack of access to contraception, lack of knowledge about various methods, and having other priorities upon resettlement such as finances, schooling, and finding a home.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine prevalence of contraception use and unmet contraceptive needs in refugees in Canada. We found a lower prevalence of contraceptive use and higher prevalence of unmet needs in this population compared with Canadian women. The Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health recommends the screening of all women of reproductive age for unmet contraceptive needs and recommends provision of contraceptive counseling to decrease unintended pregnancies.7 This recommendation is supported by our study findings.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

In this study of refugee women of reproductive age presenting to the Crossroads Clinic in Toronto, Ont, 30.8% of women did not use any form of contraception. This estimate is much higher than comparable Canadian data.

Contraceptive choices upon arrival to the clinic differed compared with Canadian data. Condoms were the most popular contraceptive choice at 23.1%, followed by sterilization at 15.4% and intrauterine devices at 7.7%.

The rate of unmet contraceptive need in this sample was 26.8%. This is higher than the reported global estimation of unmet need, as well as the unmet need reported for Canada as a whole. It is possible that unmet needs are higher in refugee populations owing to lack of access to contraception, lack of knowledge about various methods, and having other priorities upon resettlement such as finances, schooling, and finding a home.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Cette étude a montré que 30,8 % des femmes réfugiées en âge de procréer qui se présentaient à la clinique Crossroads de Toronto, en Ontario, n’utilisaient aucune forme de contraception. Cet estimé est de beaucoup supérieur aux données canadiennes comparables.

Les méthodes contraceptives choisies au moment de leur arrivée à la clinique différaient de celles utilisées au Canada. Le condom était la méthode contraceptive la plus populaire (23,1 %), suivie de la stérilisation (15,4 %) et du stérilet (7,7 %).

Dans cet échantillon, le taux de besoins de contraception non satisfaits était de 26,8 %. Ce taux est supérieur à l’estimation globale des besoins non satisfaits, mais aussi plus élevé que celui apporté pour l’ensemble du Canada. Il est possible que le taux de besoins non satisfaits soit plus élevé chez les réfugiées parce qu’elles n’ont pas facilement accès à la contraception, qu’elles connaissent mal les diverses méthodes ou parce qu’elles ont d’autres priorités durant leur réinstallation, sur le plan financier ou scolaire et pour se loger.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Contributions

Dr Aptekman performed a literature search, collected the data, analyzed the results, and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. Dr Rashid aided in conceiving the original study, provided consultation on the interpretation of results, and edited the manuscript. Ms Wright aided in conceiving the original study, provided consultation on the interpretation of results, and approved the final version. Dr Dunn aided in conceiving the study, contributed to the analysis plan, and critically reviewed the manuscript.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, World Health Organization. The right to health. Fact sheet no. 31. Geneva, Switz: United Nations; 2008. Available from: www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/Factsheet31.pdf. Accessed 2014 Nov 11. [Google Scholar]

- 2.United Nations Millennium Development Goals [website] Goal 5: improve maternal health. Geneva, Switz: United Nations; 2013. Available from: www.un.org/millenniumgoals/maternal.shtml/. Accessed 2014 Nov 11. [Google Scholar]

- 3.United Nations Population Fund. Key issues in reproductive health services. New York, NY: United Nations Population Fund; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization [website] Health topics. Reproductive health. Geneva, Switz: World Health Organization; 2013. Available from: www.who.int/topics/reproductive_health/en/. Accessed 2014 Nov 25. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guttmacher Institute, United Nations Population Fund. Fact sheet. Costs and benefits of investing in contraceptive services in the developing world. New York, NY: Guttmacher Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reproductive Health Access, Information Services in Emergencies. RAISE fact sheet: family planning. New York, NY: Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health; [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunn S, Janakiram P, Blake J, Hum S, Cheetham M, Welch V, et al. Appendix 18. Contraception: evidence review for newly arriving immigrants and refugees. In: Pottie K, Greenaway C, Feightner J, Welch V, Swinkels H, Rashid M, et al. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees. CMAJ. 2011;183(12):E824–925. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090313. Epub 2010 Jun 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.United Nations Population Fund [website] Reducing risks by offering contraceptive services. New York, NY: United Nations Population Fund; 2013. Available from: www.unfpa.org/public/home/mothers/pid/4382. Accessed 2014 Nov 25. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zurriaga O, Martínez-Beneito MA, Galmés Truyols A, Torne MM, Bosch S, Bosser R, et al. Recourse to induced abortion in Spain: profiling of users and the influence of migrant populations. Gac Sanit. 2009;23(Suppl 1):57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2009.09.012. Epub 2009 Nov 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newell A, Sullivan A, Halai R, Boag F. Sexually transmitted diseases, cervical cytology and contraception in immigrants and refugees from the former Yugoslavia. Venereology. 1998;11(1):25–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolff H, Epiney M, Lourenço AP, Costanza MC, Delieutraz-Marchand J, Andreoli N, et al. Undocumented migrants lack access to pregnancy care and prevention. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:93. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sebo P, Jackson Y, Haller DM, Gaspoz JM, Wolff H. Sexual and reproductive health behaviors of undocumented migrants in Geneva: a cross sectional study. J Immigr Minor Health. 2011;13(3):510–7. doi: 10.1007/s10903-010-9367-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolff H, Lourenço A, Bodenmann P, Epiney M, Uny M, Andreoli N, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis prevalence in undocumented migrants undergoing voluntary termination of pregnancy: a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:391. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vangen S, Eskild A, Forsen L. Termination of pregnancy according to immigration status: a population-based registry linkage study. BJOG. 2008;115(10):1309–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Global trends report: 800,000 new refugees in 2011, highest this century. UNHCR News Stories. 2012. Jun 18, Available from: www.unhcr.org/4fd9e6266.html. Accessed 2014 Nov 25.

- 16.Human Rights Research and Education Centre. By the numbers: refugee statistics. Ottawa, ON: University of Ottawa; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Temporary residents. Canada—refugee claimants present on December 1st by province or territory and urban area. In: Citizenship and Immigration Canada. Facts and figures 2011—immigration overview: permanent and temporary residents. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2012. Available from: www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/statistics/facts2011/temporary/28.asp. Accessed 2014 Nov 25. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khandor E, Koch A. The global city: newcomer health in Toronto. Toronto, ON: Toronto Public Health, Access Alliance Multicultural Health and Community Services; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gagnon AJ, Merry L, Robinson C. A systematic review of refugee women’s reproductive health. Refuge. 2002;21(1):6–17. [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization [website] Unmet need for family planning. Geneva, Switz: World Health Organization; 2013. Available from: www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/family_planning/unmet_need_fp/en/. Accessed 2014 Nov 25. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisher W, Boroditsky R, Morris B. The 2002 Canadian contraception study: part 1. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2004;26(6):580–90. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30377-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Black A, Yang Q, Wu Wen S, Lalonde AB, Guilbert E, Fisher W. Contraceptive use among Canadian women of reproductive age: results of a national survey. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009;31(7):627–40. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)34242-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Degni F, Koivusilta L, Ojanlatva A. Attitudes towards and perceptions about contraceptive use among married refugee women of Somali descent living in Finland. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2006;11(3):190–6. doi: 10.1080/13625180600557605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okanlawon K, Reeves M, Agbaje OF. Contraceptive use: knowledge, perceptions and attitudes of refugee youths in Oru refugee camp, Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2010;14(4 Spec no):16–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McLeod A, Reeve M. The health status of quota refugees screened by New Zealand’s Auckland Public Health Service between 1995 and 2000. N Z Med J. 2005;118(1224):U1702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alkema L, Kantorova V, Menozzi C, Biddlecom A. National, regional, and global rates and trends in contraceptive prevalence and unmet need for family planning between 1990 and 2015: a systematic and comprehensive analysis. Lancet. 2013;381(9878):1642–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62204-1. Epub 2013 Mar 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]