Abstract

Patient: Female, 41

Final Diagnosis: Coombs negative autoimmune hemolytic anemia

Symptoms: Dark urine • dizziness • dyspnea

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Immunoradiometric assay for RBC-IgG

Specialty: Hematology

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Anemia is a common, important extraintestinal complication of Crohn’s disease. The main types of anemia in patients with Crohn’s disease are iron deficiency anemia and anemia of chronic disease. Although patients with Crohn’s disease may experience various type of anemia, autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) in patients with Crohn’s disease, especially Coombs-negative AIHA, is very rare.

Case Report:

A 41-year-old woman with Crohn’s disease presented to our emergency room (ER) with dark urine, dizziness, and shortness of breath. The activity of Crohn’s disease had been controlled, with Crohn’s disease activity index (CDAI) score below 100 point. On physical examination, the patient had pale conjunctivae and mildly icteric sclerae. Serum bilirubin was raised at 3.1 mg/dL, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level was 1418 U/L and the haptoglobin level was <3 mg/dL. Results of direct and the indirect Coombs tests were all negative. We then measured the RBC-IgG to evaluate the possibility of Coombs-negative AIHA. The result revealed that RBC-IgG level was 352 IgG molecules/cell, with the cut-off value at 78.5 IgG molecules/cell.

Conclusions:

We report a case of Coombs-negative AIHA in a patient with Crohn’s disease with chronic anemia, diagnosed by red blood cell-bound immunoglobulin G (RBC-IgG) and treated with steroids therapy.

MeSH Keywords: Crohn Disease; Coombs Test; Anemia, Hemolytic, Autoimmune

Background

Crohn’s disease is a chronic inflammatory disease involving any part of the gastrointestinal tract. Anemia is a common and serious complication in patients with Crohn’s disease [1]. One-third of inflammatory bowel disease patients have recurrent anemia [2] and iron deficiency, vitamin B12 deficiency, folic acid deficiency, malnutrition, and inflammation. Medications can cause various kinds of anemia in Crohn’s disease. However, AIHA in patients with Crohn’s disease, especially Coombs-negative, is very rare. Here, we present a case of Coombs-negative AIHA in a patient with Crohn’s disease, diagnosed by RBC-IgG.

Case Report

A 41-year-old woman with Crohn’s disease presented to our emergency room (ER) with 2-day history of dark urine, dizziness, and shortness of breath. She had been diagnosed with terminal-ileal Crohn’s disease 4 years ago via capsule endoscopy due to bloody diarrhea at another hospital. Mesalazine (1 g/day) had been administering per oral and the activity of Crohn’s disease had been controlled, with Crohn’s disease activity index (CDAI) score below 100 points and no complaints of abdominal pain, tarry black stool, or bloody diarrhea. She did not taking other medications except for folic acid and ferrous sulfate for chronic anemia, and mesalazine for Crohn’s disease. She had no history of mechanical valve replacement or family history of hematologic disorders. Recently, she had visited a local medical center for evaluation of chronic anemia, but the specific cause could not be determined.

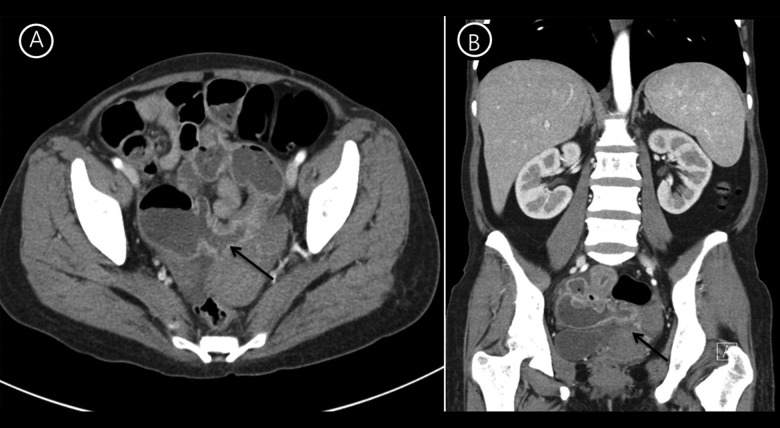

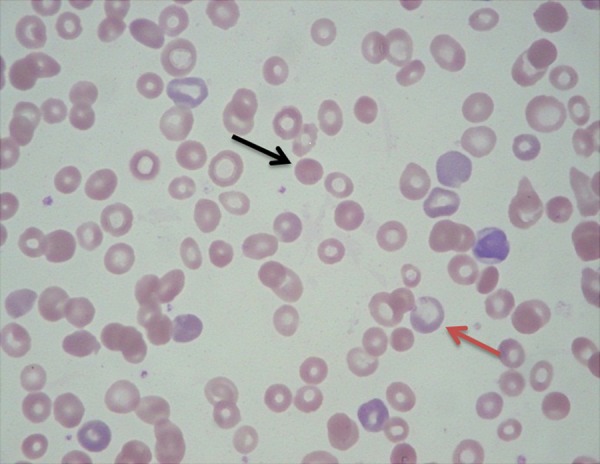

On physical examination, the patient had pale conjunctivae and mildly icteric sclerae. The liver was palpable below 2 cm from the right lower costal margin in the midclavicular line and the spleen tip was palpable at the left costal margin, but there was no palpable lymph node. Complete blood cell count revealed a hemoglobin level of 7.5 g/dL (mean corpuscular volume: 95.1 fL, mean corpuscular hemoglobin: 27.5 pg), a hematocrit of 27.8%, white blood cell count of 8.77×109/L, and 278×109/L platelets. Differential counts for white blood cells were 67% neutrophils, 20.4% lymphocytes, 11.7% monocytes, 0.2% eosinophils, and 0.6% basophils. Serum iron, total iron-binding capacity, and ferritin level were 75 ug/dL, 195 ug/dL, and 212 ug/dL, respectively. Basic metabolic panels were 140 mmol/L for sodium, 3.9 mmol/L for potassium, 108 mmol/L for chloride, 6.9 mg/dL for BUN, and 0.5 mg/dL for creatinine. Serum bilirubin was elevated at 3.1 mg/dL (direct bilirubin, 0.4 mg/dL). Aspartate aminotransferase was 111 IU/L and alanine aminotransferase was 18 IU/L. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level was 1418 U/L, and the haptoglobin level was <3 mg/dL. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 11 mm/hr and C-reactive protein was 4.35 mg/dL, with no signs of infectious diseases. Abdominal CT (Figure 1) revealed active Crohn’s disease involving the ileum with multiple segmental wall thickening, prominent mucosal enhancement with skip areas in the ileum, and CDAI score was above 200 points. A peripheral blood smear (Figure 2) showed moderate anisocytosis and spherocytosis, with microcytic hypochromic red blood cells. The reticulocyte count was 7.41% and reticulocyte production index was 3.05%. There were no bite cells, or Heinz bodies. The clinical and hematological features were suggestive of hemolytic anemia and the patient was admitted to determine the cause of hemolysis. Mesalazine was discontinued for 5 days because it could not be excluded as contributing to hemolysis, but hemolysis was continued. Erythrocyte enzymes (glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and pyruvate kinase) and flow cytometric analysis of glycophosphatidylinositol anchored proteins for paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria were normal. The direct and the indirect Coombs test result, including anti-Immunoglobulin (Ig) G, anti-Ig A, anti-Ig M, anti-C3, and C3d, were all negative. We strongly suspected AIHA because of a blood smear with morphologic evidence of hemolysis, and serial measurement of markers of hemolysis persisted, so we repeated Coombs tests and the results were again negative. Finally, we measured the RBC-IgG by immunoradiometric assay to evaluate the possibility of Coombs-negative AIHA. The result revealed that RBC-IgG level was 352 IgG molecules/cell, with the cutoff value at 78.5 IgG molecules/cell [3]. These data supported a diagnosis of Coombs-negative AIHA due to the small number of RBC-IgG, below the threshold, and a direct antiglobulin test that differs from the conventional tube technique. We finally diagnosed the patient as having Coombs-negative AIHA combined with Crohn’s disease. During hospitalization, the patient received 1 mg/kg of oral prednisolone. Two weeks later, the patient’s hemoglobin level was improved to 8.6 g/dl and there was improvement, with a reduction of the reticulocyte count to 4.5% and LDH to 145 IU. She took 30 mg/day of steroids for the next 2 months and there have been no more signs of hemolysis. Thereafter, steroid dose was tapered and now she did not need steroid for AIHA.

Figure 1.

Abdominal CT reveals active Crohn’s disease involving the ileum, with multi-segmental wall-thickening prominent and mucosal enhancement with skip areas in the ileum (A: axial view, B; coronal view).

Figure 2.

Peripheral blood smear shows spherocytosis (black arrow), reticulocytosis (red arrow), and microcytic hypochromic red blood cells.

Discussion

Crohn’s disease is a chronic inflammatory disease affecting the gastrointestinal tract at any part from the mouth to the anus. The etiology of Crohn’s disease is not clear, but it seems to be caused by a combination of environmental factors and genetic predisposition. Besides affecting the gastrointestinal tract, a variety of extraintestinal manifestations have been recognized in 20–40% of patients with Crohn’s disease [1]. Extraintestinal manifestations of Crohn’s disease include anemia, erythema nodosum, peripheral arthropathy, cutaneous ulcerations, and uveitis. Among these, anemia is commonly complicating CD, affecting quality of life, cognitive function, the ability to work [4]. The main causes of anemia in Crohn’s disease are iron deficiency anemia and anemia of chronic diseases. In addition, vitamin B12 deficiency, folic acid deficiency, and therapeutic drugs like sulfasalazine and methotrexate are able to cause anemia in Crohn’s disease[5].

AIHA exists as a primary disorder in CD 50% of cases, and in the remaining 50% of CD cases it is associated with other conditions that include lymphoproliferative diseases, autoimmune disorders, and drug-induced conditions. Inflammatory bowel disease is regarded as an autoimmune disorder, like AIHA [6], and autoimmune disorders tend to co-exist [7,8]. The association between AIHA and ulcerative colitis is relatively well documented [9], but the association between AIHA and Crohn’s disease appears to be extremely rare [10].

In the diagnosis of AIHA, Coombs test (in conjunction with direct antiglobulin test) remains the main serological assay [11]. Coombs-negative AIHA is characterized by laboratory evidence of in vivo hemolysis, together with a negative Coombs test performed by column agglutination method in patients clinically suspected with AIHA. A negative Coombs test result in patients with AIHA could be due to low levels of antibodies on red cell membranes, the low sensitivity of the conventional Coombs test tube method, or other autoantibodies like IgA and IgM. The immunoradiometric assay for RBC-IgG can be used to diagnose patients in whom column agglutination method does not detect low levels of red cell autoantibodies. RBC-IgG levels should be measured for the diagnosis of Coombs-negative AIHA and the cut-off value used should be 78.5 molecules/cell with 100% sensitivity and 94% specificity when or if RBC-IgG is measured before treatment [3].

In this case, Coombs-negative non-immune hemolytic anemia caused by drugs, toxins, infections, and other hemolytic diseases (e.g., paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, hemolytic uremic syndrome, and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura) could be excluded. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia was strongly suspected clinically, despite the negative Coombs test result and negative Coombs anti-IgA and anti-IgM. The immunoradio-metric assay for RBC-IgG was helpful in making a diagnosis of Coombs-negative AIHA due to the low RBC-IgG, so we did not test for the possibility of low-affinity autoantibodies. It is important to distinguish Coombs-negative AIHA from other hemolysis because steroid treatment has a major effect on AIHA [12]. Coombs-negative AIHA patients respond equally well to steroid treatments and generally have a milder course of disease than patients with Coombs-positive AIHA [11]. Clinically, Coombs-negative AIHA seems to be nearly equivalent with Coombs-positive AIHA.

Conclusions

The detection of Coombs-negative AIHA cases is important because AIHA can be a life-threatening condition involving intense hemolysis, shock, and death. Coombs-negative AIHA needs to be recognized so that an early diagnosis can be made and appropriate therapy can be given.

References:

- 1.Williams H, Walker D, Orchard TR. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2008;10(6):597–605. doi: 10.1007/s11894-008-0108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiss G, Goodnough LT. Anemia of chronic disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):1011–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamesaki T, Oyamada T, Omine M, et al. Cut-off value of red-blood-cell-bound IgG for the diagnosis of Coombs-negative autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Am J Hematol. 2009;84(2):98–101. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kulnigg S, Gasche C. Systematic review: managing anaemia in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24(11–12):1507–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gasche C, Lomer MC, Cavill I, Weiss G. Iron, anaemia, and inflammatory bowel diseases. Gut. 2004;53(8):1190–97. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.035758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wen Z, Fiocchi C. Inflammatory bowel disease: autoimmune or immune-mediated pathogenesis? Clin Dev Immunol. 2004;11(3–4):195–204. doi: 10.1080/17402520400004201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Triolo TM, Armstrong TK, McFann K, et al. Additional autoimmune disease found in 33% of patients at type 1 diabetes onset. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(5):1211–13. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neuhausen SL, Steele L, Ryan S, et al. Co-occurrence of celiac disease and other autoimmune diseases in celiacs and their first-degree relatives. J Autoimmun. 2008;31(2):160–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mañosa M, 1, Domènech E, Sánchez-Delgado J, et al. [Autoimmune hemolytic anemia associated with ulcerative colitis] Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;28(5):283–84. doi: 10.1157/13074063. [in Spanish] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plikat K, Rogler G, Scholmerich J. Coombs-positive autoimmune hemolytic anemia in Crohn’s disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17(6):661–66. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200506000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamesaki T, Toyotsuji T, Kajii E. Characterization of direct antiglobulin test-negative autoimmune hemolytic anemia: a study of 154 cases. Am J Hematol. 2013;88(2):93–96. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilliland B. Coombs – negative immune hemolytic anemia. Semin Hematol. 1976;13(4):267–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]