Abstract

Therapies that promote tolerance in solid organ transplantation will improve patient outcomes by eliminating the need for long-term immunosuppression. To investigate mechanisms of rapamycin-induced tolerance, C3H/HeJ mice were heterotopically transplanted with MHC-mismatched hearts from BALB/cJ mice and were monitored for rejection after a short course of rapamycin treatment. Mice that had received rapamycin developed tolerance with indefinite graft survival, whereas untreated mice all rejected their grafts within 9 days. In vitro, splenic mononuclear cells from tolerant mice maintained primary CD4+ and CD8+ immune responses to donor antigens consistent with a mechanism that involves active suppression of immune responses. Furthermore, infection with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus strain WE led to loss of tolerance suggesting that tolerance could be overcome by infection. Rapamycin-induced, donor-specific tolerance was associated with an expansion of regulatory T (Treg) cells in both the spleen and allograft and elevated plasma levels of fibrinogen-like protein 2 (FGL2). Depletion of Treg cells with anti-CD25 (PC61) and treatment with anti-FGL2 antibody both prevented tolerance induction. Tolerant allografts were populated with Treg cells that co-expressed FGL2 and FoxP3, whereas rejecting allografts and syngeneic grafts were nearly devoid of dual-staining cells. We examined the utility of an immunoregulatory gene panel to discriminate between tolerance and rejection. We observed that Treg-associated genes (foxp3, lag3, tgf-β and fgl2) had increased expression and pro-inflammatory genes (ifn-γ and gzmb) had decreased expression in tolerant compared with rejecting allografts. Taken together, these data strongly suggest that Treg cells expressing FGL2 mediate rapamycin-induced tolerance. Furthermore, a gene biomarker panel that includes fgl2 can distinguish between rejecting and tolerant grafts.

Keywords: fgl2, regulatory T cell, transplantation, tolerance

Introduction

Transplantation currently remains the most effective treatment for patients with end-stage organ failure. However, the progress achieved in transplantation has been limited by the need for long-term immunosuppression, which is associated with an increased incidence of opportunistic infections, cardiovascular disease, renal failure and malignancy.1 Therefore, a goal for transplantation must be to minimize or eliminate the need for immunosuppression through strategies that induce donor-specific tolerance.

A number of reports have identified the potential of rapamycin to induce tolerance and multiple mechanisms have been proposed to explain its tolerogenic effects including expansion of CD4+ CD25+ FoxP3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells.2–6 Rapamycin treatment may lead to an increase in the number of Treg cells by promoting the de novo differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells into Treg cells by blocking the mTOR-dependent inhibition of foxp3 transcription.7 Moreover, the preferential Treg cell expansion with rapamycin treatment may also be the result of the resistance of Treg cells to the anti-proliferative effects of this drug.8 Nevertheless, studies using rapamycin to expand Treg cells in vivo have not conclusively shown whether these Treg cells can promote tolerance to fully mismatched allografts in a donor-specific manner.

Donor-specific Treg cells could promote tolerance to transplanted grafts through various effector mechanisms including increased expression of CTLA-4 and lymphocyte activating gene 3, both of which induce a negative regulatory signal and prevent dendritic cell (DC) maturation.9–11 Moreover, Treg cells promote apoptosis of T lymphocytes by depriving them of interleukin-2 (IL-2) and by releasing cytolytic molecules such as granzyme B and perforin.12,13 Effector lymphocyte maturation can also be prevented by release of inhibitory cytokines including IL-10, IL-35 and transforming growth factor-β. Fibrinogen-like protein 2 (FGL2) is an immunoregulatory cytokine that has been shown to have an important role in Treg-mediated tolerance.14 Upon secretion by Treg cells, FGL2 binds to FcγRIIB/RIII primarily expressed on antigen-presenting cells including macrophages, DC and B cells. This binding inhibits maturation of antigen-presenting cells, which results in a decrease in T effector cell function.15,16

Novel biomarkers are needed that can distinguish between transplant recipients who are at risk of rejection and those who have developed tolerance. It is unlikely that a single biomarker will be able to identify patients who have achieved tolerance; instead, panels that incorporate multiple biomarkers will probably be necessary to identify tolerant recipients.17–19 Such a biomarker panel would allow for a tolerant state to be identified and for immunosuppression to be safely reduced or withdrawn in selected recipients. In clinical heart transplantation, expression of a set of genes in peripheral blood mononuclear cells was shown to have a high negative predictive value for rejection.20 However, this gene panel did not identify tolerant heart transplant recipients. We and others have shown that Treg-associated genes are increased in grafts from tolerant animals and have suggested that expression of these genes may serve as a basis for a tolerance biomarker panel.19

The goal of the present study was to further explore the mechanisms of rapamycin-induced tolerance in a murine fully MHC-mismatched heterotopic heart transplant model and to investigate the utility of a panel of immunoregulatory-associated genes to distinguish between tolerance and rejection. Here we demonstrate that Treg cells expanded in vivo by rapamycin and expressing FGL2 induce tolerance in a donor-specific manner. A gene biomarker panel that includes fgl2 also distinguished between rejecting and tolerant grafts. Together, these findings advance our understanding of tolerogenic mechanisms and provide a novel diagnostic tool for detecting tolerance in transplantation.

Materials and methods

Mice

Female C3H/HeJ (H-2k, tlr4−/−), C3H/HeOuJ (H-2k, tlr4+/+), BALB/cJ (H-2d) and C57BL/6J (H-2b) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Animal protocols were approved by the University Health Network in accordance with guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care.

Heterotopic cardiac transplantation

Intra-abdominal heterotopic cardiac transplants were performed as described previously.21 Donor hearts were harvested from 4 to 6-week-old BALB/cJ or C3H/HeJ mice following ligation of the pulmonary veins, inferior vena cava and superior vena cava. The main pulmonary artery and ascending aorta were then excised and attached through end-to-side anastomoses to the inferior vena cava and abdominal aorta of recipient C3H/HeJ or C3H/HeOuJ mice. Rejection was defined as complete cessation of heart beating and confirmed by direct visual examination.

Tolerance protocol

The tolerance protocol was modified from that described previously.22 Recipient mice were treated with 0·4 mg/kg rapamycin (Wyeth-Ayerst, Princeton, NJ) by intraperitoneal injection on day 0 and 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14 and 16 days post transplant. To assess the role of Treg cells and FGL2 in tolerance induction, groups of mice also received intraperitoneal injection of 250 µg of anti-CD25 antibody (PC61; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) or 250 µg of anti-FGL2 antibody (9D8; Veritas, Toronto, Canada) or 250 µg IgG1 isotype control antibody (RTK2071; Biolegend, San Diego, CA) 2 days before transplantation and on day 0 and 3, 6, 9, 12 and 15 days post transplantation concurrently with rapamycin. The following controls for the experimental groups of animals were included: an allogeneic transplant group (BALB/cJ → C3H/HeJ) that received cyclosporin A (Novartis, Basel, Switzerland) at a concentration of 20 mg/kg subcutaneously every day for 16 days;22 an allogeneic transplant group (BALB/cJ → C3H/HeJ) that did not receive any immunosuppressive therapy; a syngeneic transplant group (C3H/HeJ → C3H/HeJ) that did not receive immunosuppression; a non-transplanted C3H/HeJ group that did not receive immunosuppression and a non-transplanted C3H/HeJ group that received rapamycin using the tolerance protocol.

Skin grafts

To assess if tolerance was donor-specific, full thickness skin, 1 cm2 in size, from donor (BALB/cJ) or third-party (C57BL/6J) mice was grafted onto the dorsum of rapamycin-treated or non-treated C3H/HeJ mice 30 days after the cardiac transplant. Skin grafts were then monitored daily for rejection.15

Histological studies

Allografts or non-transplanted hearts were processed for routine histology or immunohistochemistry. For immunoperoxidase staining, FoxP3 expression was detected using a rat anti-mouse/rat FoxP3 antibody (FJK-16s; eBioscience, San Diego, CA) and CD3 expression was detected using a rat anti-mouse CD3ε antibody (17A2; eBioscience). For morphometric analysis, stained cells were identified using the program Spectrum version 10.2.2.2317 (Aperio Technologies Inc., Vista, CA).

For co-localization studies of FoxP3 and FGL2 within transplanted heart grafts, hearts were recovered, embedded in OCT and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Tissue sections 5 µm in thickness were cut from four levels that were 300 µm apart. Sections were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 20 min and permeabilized using a solution of 0·5% Triton X-100/0·05% Tween-20 in PBS. Sections were stained with a primary antibody cocktail containing a 1 in 3000 dilution of rabbit polyclonal anti-FGL2 that was produced in our laboratory and a 1 in 100 dilution of rat anti-FoxP3 (eBioscience). A secondary antibody cocktail containing a 1 in 200 dilution of both Alexafluor 488 goat anti-rabbit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and Alexafluor 555 goat anti-rat (Life Technologies) was used to visualize FGL2+ and FOXP3+ cells. Nuclei were stained using a working solution of DAPI (Life Technologies). The results of the double immunofluorescent staining were captured on a TISSUEscope 4000 scanning laser confocal microscope (Huron Technologies, Waterloo, Canada) and analysed using a Definiens image analysis platform (Definiens, Carlsbad, CA).23

Splenic mononuclear cell isolation

Spleens were harvested and dissected into smaller segments. Splenic mononuclear cells (SMNC) were dissociated from connective tissue using a 40-μm nylon filter and isolated using lympholyte M density separation medium (Cedarlane, Burlington, Canada).

Mixed lymphocyte reaction

Responder SMNC (2 × 105) were isolated from transplanted and non-transplanted mice and were co-cultured with irradiated stimulator cells (8 × 105) from donor (BALB/cJ), third-party (C57BL/6J), or syngeneic (C3H/HeJ) mice at 37° for 4 days in α-modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Scientific HyClone, Logan, Utah) and 0·5 μm 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). For blocking studies, 10 μg/ml of either anti-FGL2 (6D9; Abnova, Taiwan) or IgG control (RTK2071; Biolegend) was added to cultures. Proliferation was enumerated by either measurement of [3H]thymidine incorporation or CFSE dilution.

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte assay

Responder SMNC were co-cultured with irradiated stimulator SMNC from donor or third party mice at a 1 : 1 ratio for 5 days at 37°. A20 (ATCC) (H-2d) and EL4 (ATCC) (H-2b) cell lines were used as targets and were incubated with 1 mCi/ml sodium chromate (Na2CrO4) (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). A20 and EL4 cells were mixed with the appropriate responder cells at 25 : 1, 10 : 1, 5 : 1 and 1 : 1. Supernatants were collected and counted using a Packard Microplate Scintillation Counter (PerkinElmer). Maximum lysis was determined by addition of Triton-X100 (Sigma-Aldrich) and spontaneous background release was assessed by incubating target cells alone. Per cent specific lysis was calculated with the following formula: per cent cytotoxicity = [(experimental release − background release)]/[(maximum lysis − background release)] × 100%, as previously described.24

Infection with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus strain WE

Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) WE was obtained as a gift from the laboratory of Dr Pamela Ohashi (Ontario Cancer Institute, Toronto, Canada) and was propagated on L929 cells. Virus was purified from virus containing supernatants by banding on isopycnic Renografin-76 (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO) gradients as described previously.25 Cardiac tissues both pre- and post-infection were assessed for presence of virus by staining for LCMV nucleoprotein by immunohistochemistry as previously described.25 To examine whether a viral infection might lead to loss of tolerance, mice that had received fully allogeneic heart transplants and were tolerant and mice that had received syngeneic grafts were infected with 2 × 106 plaque-forming units of LCMV WE for effect on heart function as determined by heart palpation. At time of rejection, hearts were recovered and stained for presence of virus and routine histology.

Flow cytometry

Fluorescein isothiocyanate-, allophycocyanin-, phycoerythrin- and peridinin-chlorophyll proteins–carotenoid-protein 5.5-conjugated monoclonal antibodies against mouse CD4 (RM4-5), Foxp3 (FJK-16S), CD3 (145-2C11), CD25 (PC61.5, 3C7) and their isotype controls were purchased from eBioscience and Biolegend. Propidium iodide and fixable viability dye eFluor 450 (eBioscience) were used as markers of cell viability. SMNC were resuspended and anti-mouse CD16/32 (eBioscience) was added to block Fc receptors. For intracellular staining, cells were incubated overnight with fixation and permeabilization solution (eBioscience). SMNC were then stained for intracellular FoxP3 with a phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-mouse/rat FoxP3 antibody (eBioscience). Flow cytometry was performed on a BD LSR II flow cytometer (BD Bioscience, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Data were analysed using FlowJo software version 8.8.6 (Tree Star Inc, Ashland, OR). First, the singlet gate was set up and forward and side scatter were used to gate on lymphocytes. Viable cells were gated based on the propidium iodide or eFluor 450 negative populations when appropriate.

Flow cytometry for donor-specific antibodies

Donor SMNC were incubated with recipient sera. SMNC were then incubated with FITC-conjugated polyclonal anti-mouse IgG (Immunology Consultants Laboratory, Newberg, OR) followed by incubation with allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-mouse CD3 (145-2C11; eBioscience). Levels of donor-specific antibodies were determined on a BD LSR II flow cytometer (BD Bioscience) gating on the CD3+ fraction and were reported as mean fluorescence intensity.

FGL2 sandwich ELISA

The sandwich FGL2 ELISA was performed as described previously.26 Ninety-six-well plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY) were coated overnight at 4° with anti-FGL2 capture antibody (6H12; Veritas). Plasma diluted 1 : 10 was added and incubated for 1 hr before addition of polyclonal rabbit anti-FGL2 antibody (Veritas). A horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (Bethyl, Montgomery, TX) was added to detect polyclonal anti-FGL2 binding. Following addition of tetramethylbenzidine (Sigma-Aldrich), absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a Multiskan Ascent ELISA plate reader (Titertek Instruments Inc., Huntsville, AL).

Multiplex RT-PCR

Primers were generated for Treg genes that are known to be involved with allograft rejection, allograft recognition, signal transduction, T-cell activation and differentiation, adhesion and migration and immune effector responses as well as five housekeeping genes and one internal control (see Supporting information, Table S1).27 The expression patterns of these genes were analysed with the Genome-Lab GeXP analysis system by multiplex RT-PCR (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). Cardiac allografts were harvested and immersed in RNAlater (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). For expression analysis, RNA was added to a 96-well microplate (Beckman Coulter) along with kanamycin resistance gene RNA, which was an internal control. RT-PCR was performed using primers generously provided by Beckman Coulter. Expression values were normalized to the housekeeping gene hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase and subsequently expressed as a ratio compared with gene expression in non-transplanted hearts. At each time-point, the mean expression from three allografts is shown. Results from GeXP analysis were confirmed using quantitative PCR and data analysis was performed using the LightCycler480 system (Roche, Basel, Switzerland).

Statistics

Log-rank tests were performed to assess the statistical significance of survival data plotted on Kaplan–Meier curves. Unless otherwise specified, statistical significance of other studies was assessed using the analysis of variance test followed by a Tukey's honestly significant difference test as a post-hoc analysis for group comparisons. Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 5 software (Graphpad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). Student's t-test was used for morphometric analysis. Differences with P ≤ 0·05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

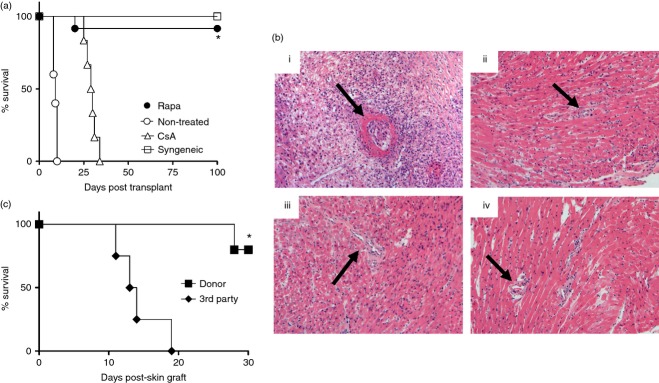

Rapamycin promotes cardiac allograft tolerance

BALB/cJ heart allografts transplanted into C3H/HeJ mice without immunosuppressive therapy were all rejected (mean survival time, 9·0 days), whereas 11 out of 12 allografts from recipients treated with rapamycin continued to function until time of death (> 100 days) similar to syngeneic grafts (Fig. 1a). Allografts from mice that received cyclosporin A were rejected between days 10 and 19 following cessation of cyclosporin A therapy.

Figure 1.

Rapamycin treatment leads to indefinite heart allograft survival (tolerance) in a donor-specific manner. (a) Survival of BALB/cJ hearts transplanted into C3H/HeJ recipient mice. Recipient groups included non-treated (○: mean survival time = 9·0 days, n = 5), rapamycin-treated (•: survival time > 100 days, n = 12), cyclosporin A-treated (▵: mean survival time = 29·5 days, n = 6), and syngeneic (C3H/HeJ → C3H/HeJ) transplants (□: survival time > 100 days, n = 5). *P < 0·05 versus non-treated. (b) Histopathology of heart allografts (H&E stain; magnification 100×). (i) Allografts from non-treated recipients [post-operative day (POD) 7], black arrow indicates vasculitis. (ii) Allograft from rapamycin-treated recipient (POD 100), black arrow indicates normal appearing vessel. (iii) Syngeneic control graft (POD 100). (iv) Non-transplanted control heart. No evidence of vasculitis (black arrows) is present in either control. (c) Survival curves of donor BALB/cJ (▪: survival time > 30 days, n = 5) and third-party C57BL/6J (♦: mean survival time = 14·3 days, n = 4) skin grafts after heart transplantation. *P < 0·05 versus third party. Rapa, rapamycin. CsA, cyclosporin.

C3H/HeJ mice are known to have a mutation in the tlr4 gene, which results in defective Toll-like receptor 4 signalling.28 To determine if a mutation in the tlr4 gene facilitated tolerance induction, BALB/cJ allografts were also transplanted into tlr4+/+ C3H/HeOuJ endotoxin-sensitive recipients. All heart allografts survived indefinitely when these mice received the rapamycin protocol (≥ 100 days, data not shown) demonstrating that tolerance was not dependent on defective tlr4.

Histological examination of allografts from non-treated, rejecting mice showed dense mononuclear cell infiltrates with severe myocyte necrosis and vasculitis by day 7 post transplant (Fig. 1b). Similar pathology was seen in heart grafts following cessation of cyclosporin A on post-operative day 30, demonstrating that cyclosporin A did not induce tolerance (data not shown). Hearts from rapamycin-treated, tolerant mice at 100 days after transplantation were near normal and resembled syngeneic grafts and non-transplanted hearts. However, in all of these grafts, small foci of mononuclear cell infiltrates were observed.

Four of five donor BALB/cJ skin grafts survived indefinitely (≥ 30 days) in tolerant mice, whereas four out of four skin grafts from third-party mice were rejected (mean survival time 14·3 days) demonstrating that tolerance was donor-specific (Fig. 1c). Additional studies demonstrated that BALB/cJ skin grafts survived > 100 days in tolerant mice (data not shown).

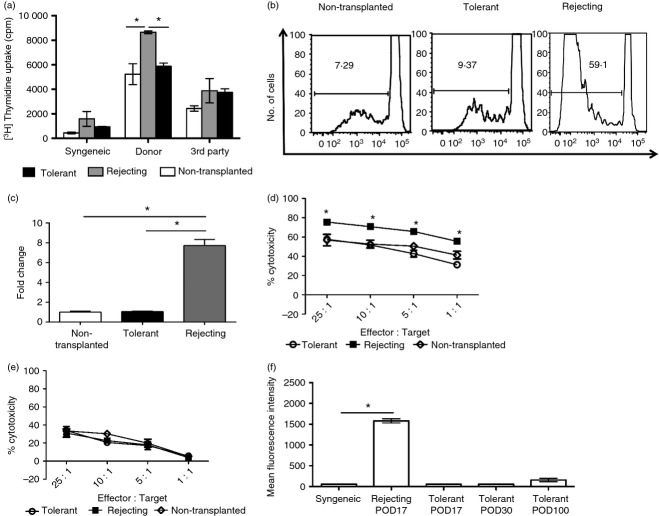

Lymphocytes from tolerant mice maintain primary immune responses to donor antigens in vitro

In a one-way mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) described above, SMNC from tolerant mice had similar proliferation to donor cells compared with SMNC from non-transplanted mice and had significantly less proliferation to donor cells compared with SMNC from rejecting mice (Fig. 2a). Proliferation was not statistically different between the groups when challenged with cells from a third party. There was also minimal proliferation when responder cells were challenged with syngeneic cells. The results were confirmed in a second set of MLR assays performed with CFSE-labelled responder SMNC challenged with donor cells (Fig. 2b,c).

Figure 2.

Lymphocytes from tolerant mice maintain primary immune responses to donor antigens in vitro. (a) Mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) assay. Splenic mononuclear cells (SMNC) were isolated from non-transplanted (□), post-operative day (POD) 100 non-treated and rejecting ( ), and POD 100 rapamycin-treated and tolerant (▪) C3H/HeJ mice and co-cultured with irradiated SMNC from syngeneic (C3H/HeJ), donor (BALB/cJ) or third-party (C57BL/6J) mice. *P < 0·05 versus rejecting group. (b) CFSE proliferation profiles of (i) non-transplanted, (ii) POD 30 tolerant, and (iii) POD 30 rejecting C3H/HeJ SMNC stimulated with irradiated donor SMNC. (c) Quantification of CFSE proliferation data. Proliferation of SMNC from the different groups is shown as a fold change compared with SMNC from non-transplanted mice (mean ± SEM). *P < 0·05 versus rejecting group. (d, e) Cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) assay. SMNC were isolated from non-transplanted controls (♢), POD 100 tolerant (

), and POD 100 rapamycin-treated and tolerant (▪) C3H/HeJ mice and co-cultured with irradiated SMNC from syngeneic (C3H/HeJ), donor (BALB/cJ) or third-party (C57BL/6J) mice. *P < 0·05 versus rejecting group. (b) CFSE proliferation profiles of (i) non-transplanted, (ii) POD 30 tolerant, and (iii) POD 30 rejecting C3H/HeJ SMNC stimulated with irradiated donor SMNC. (c) Quantification of CFSE proliferation data. Proliferation of SMNC from the different groups is shown as a fold change compared with SMNC from non-transplanted mice (mean ± SEM). *P < 0·05 versus rejecting group. (d, e) Cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) assay. SMNC were isolated from non-transplanted controls (♢), POD 100 tolerant ( ) and POD 100 rejecting (▪) C3H/HeJ graft recipients and co-cultured with donor A20 (d) or third-party EL4 (e) target cells. *P < 0·05 versus rejecting group. (f) Sera from syngeneic, tolerant and rejecting recipients were analysed for the presence of donor-specific antibody (DSA) by flow cytometry. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0·05 versus syngeneic control. Data for (a), (c) and (f) have three or four mice per group. Data for (b), (d) and (e) are representative of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Rapa, rapamycin.

) and POD 100 rejecting (▪) C3H/HeJ graft recipients and co-cultured with donor A20 (d) or third-party EL4 (e) target cells. *P < 0·05 versus rejecting group. (f) Sera from syngeneic, tolerant and rejecting recipients were analysed for the presence of donor-specific antibody (DSA) by flow cytometry. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0·05 versus syngeneic control. Data for (a), (c) and (f) have three or four mice per group. Data for (b), (d) and (e) are representative of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Rapa, rapamycin.

To assess cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) activity, 51chromium release assays were performed. At all effector-to-target ratios, SMNC from tolerant mice had equivalent cytotoxicity toward A20 donor targets compared with SMNC from non-transplanted controls and reduced cytotoxicity compared with SMNC from rejecting mice (Fig. 2d). When challenged with third-party EL4 targets, SMNC responses from all three groups were equivalent at all effector-to-target ratios (Fig. 2e).

Flow cytometry was performed to determine if recipient mice develop donor-specific IgG antibody. Non-treated rejecting mice developed a robust antibody response to donor antigens by day 17 after transplantation, whereas rapamycin-treated tolerant mice failed to develop donor-specific antibody even by day 100 (Fig. 2f). Together, these studies further support the assertion that rapamycin treatment leads to allograft tolerance in a donor-specific manner.

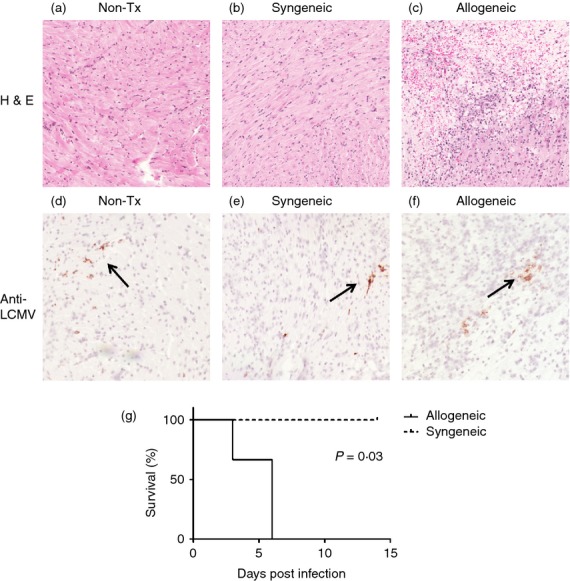

Infection with LCMV strain WE results in loss of tolerance

To examine whether a viral infection might lead to loss of tolerance, we infected mice that were tolerant to allotransplants and mice that had received syngeneic grafts with 2 × 106 plaque-forming units of LCMV WE, a strain of LCMV that causes an acute self-contained viral infection, on day 30 post transplant (after the end of immunosuppressive treatment). Although all mice survived after the infection, all tolerant allografts were rejected by day 6 post LCMV infection, whereas syngeneic grafts continued to beat until time of killing on day 14 at which time the virus had been cleared (Fig. 3g). Histological examination of rejecting grafts showed a large mononuclear cell infiltrate compatible with the histological picture of an acute cellular rejection (Fig. 3c). Syngeneic grafts all continued to function normally after LCMV infection and at death showed no evidence of rejection or inflammation (Fig. 3b). Grafts were also stained for the presence of virus and focal viral deposits were seen in non-transplanted hearts, rejecting allogeneic grafts and non-rejecting syngeneic grafts (Fig. 3d–f). These data suggest that donor-specific T cells are still present and able to respond after rapamycin treatment and that viral infection leads to loss of tolerance.

Figure 3.

Infection with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) leads to rejection of tolerant allografts. Hearts were isolated from non-transplanted (Non-Tx) mice and mice that had received syngeneic grafts and allografts 6 days post-infection with 2 × 106 plaque-forming units of LCMV. Mice that had received allografts were tolerant to the grafts following a short course of rapamycin. (a–c) Haematoxylin & eosin staining (magnification 200×) revealed significant inflammatory cell infiltrates and myocyte necrosis at day 6 post-LCMV infection in allografts consistent with the histological picture of acute cellular rejection and loss of tolerance. Non-transplanted hearts and syngeneic grafts did not show any signs of rejection or inflammation. (d–f) Anti-LCMV immunostaining (black arrow) (magnification 200×) showed near equivalent distribution of nucleocapsid protein in non-transplanted hearts, syngeneic grafts and allografts. (g) Survival of heart grafts is shown as a Kaplan–Meir survival curve post-LCMV infection. The images and survival curve are representative of three mice per group.

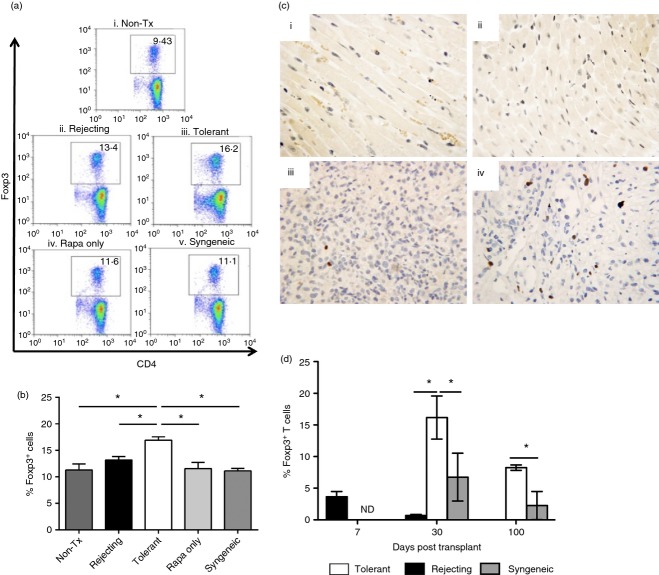

FoxP3+ Treg cells are increased in grafts and spleens of tolerant recipients

To investigate whether rapamycin-induced tolerance was related to Treg cell expansion in vivo, we next enumerated CD4+ FoxP3+ Treg cells in the spleens of recipient mice by flow cytometry. Indeed, tolerant mice exhibited an increase in both the total number (see Supporting information, Fig. S1) and proportion of FoxP3+ cells (as a percentage of total splenic CD4+ cells) as compared with rejecting and other control mice (Fig. 4a,b). Next, we measured the numbers of FoxP3+ cells in allografts by immunostaining with morphometric analysis. On post-operative day 7, only small numbers of FoxP3+ cells were observed in rejecting grafts, when compared with the dense mononuclear cell infiltrate that was present. In syngeneic grafts studied 100 days post transplant and non-transplanted hearts, few if any FoxP3+ cells were found. In contrast, large numbers of FoxP3+ cells were found in allografts from tolerant mice on post-operative day 100 (Fig. 4c). By morphometry, the percentage of FoxP3+ cells at day 30 was significantly increased in allografts from tolerant mice (16·2 ± 3·4%) compared with allografts from rejecting mice (0·7 ± 0·2%) and syngeneic controls (6·7 ± 3·9%, Fig. 4d). At day 100, increased numbers of Foxp3+ cells persisted in grafts from tolerant mice compared with grafts from syngeneic recipients studied at the same time-point. Analysis could not be performed on allografts from rejecting mice at day 100 because these grafts were necrotic and did not contain viable cells. Although the percentage of FoxP3+ cells in allografts from rejecting mice were higher at day 7 than day 30, the percentage of FoxP3+ cells at day 7 was still less than in allografts from tolerant mice.

Figure 4.

Regulatory T (Treg) cells are increased in tolerant mice. (a) Flow cytometry plots of the splenic Treg population (FoxP3+) as a percentage of CD4+ splenic mononuclear cells (SMNC) from (i) non-transplanted (Non-Tx), (ii) post-operative day (POD) 30 rejecting, (iii) POD 30 tolerant, (iv) rapamycin-only non-transplanted (Rapa only), and (v) POD 30 syngeneic C3H/HeJ recipients are shown. Graphs are representative of three independent experiments. (b) Quantification of flow cytometry plots. FoxP3+ cells are shown as a percentage of CD4+ SMNC from the above groups with three or four mice per group (mean ± SEM). *P < 0·05 versus tolerant group. (c) FoxP3 immunohistochemical staining (magnification 400×) in (i) non-transplanted hearts, (ii) POD 100 syngeneic grafts, (iii) POD 7 rejecting and (iv) POD 100 tolerant heart allografts. (d) Morphometric analysis of allografts. Cells positive for FoxP3 are shown as a percentage of CD3+ graft-infiltrating cells from syngeneic ( ), tolerant (□) and rejecting (▪) groups at different time-points after transplantation. A minimum of three mice per group at each time-point. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0·05 versus rejecting group or syngeneic group. ND, not determined.

), tolerant (□) and rejecting (▪) groups at different time-points after transplantation. A minimum of three mice per group at each time-point. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0·05 versus rejecting group or syngeneic group. ND, not determined.

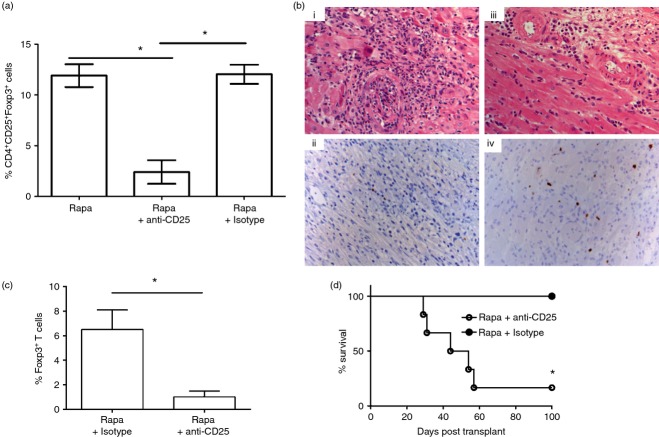

CD4+ CD25+ FoxP3+ Treg cells are necessary for rapamycin-induced graft tolerance

To determine if Treg cells were necessary for development of tolerance, in vivo depletion studies using the mAb PC61 (anti-CD25) were performed. Treatment with PC61 resulted in a decrease in splenic CD4+ CD25+ FoxP3+ cells compared with treatment with an isotype control antibody (Fig. 5a). Furthermore, numbers of Treg cells in PC61-treated mice were found to be markedly reduced in cardiac grafts as determined by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 5b) and morphometry (Fig. 5c). Treatment with PC61 also prevented tolerance induction. Five of six allografts were rejected when PC61 was given to mice that also received rapamycin (mean survival time, 52·5 days), whereas allografts from mice treated with the isotype control antibody survived indefinitely (survival time > 100 days) (Fig. 5d). Histology confirmed that administration of PC61 led to acute cellular rejection (Fig. 5b). Collectively, these results confirmed that CD4+ CD25+ FoxP3+ Treg cells expanded in vivo with rapamycin are necessary for induction of tolerance.

Figure 5.

CD4+ CD25+ FoxP3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells are necessary for rapamycin-induced graft tolerance. (a) CD4+ CD25+ FoxP3+ Treg cells are shown as percentages of CD4+ splenic mononuclear cells (SMNC) from rapamycin treated (Rapa), anti-CD25 treated (Rapa + anti-CD25), and IgG isotype control treated (Rapa + Isotype) recipients. Mice received an intraperitoneal injection of 250 µg of anti-CD25 antibody (PC61) or 250 µg of isotype control antibody 2 days before transplantation and on day 0 and 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15 days post-transplantation concurrently with rapamycin. Minimum of three mice per group. *P < 0·05 compared with Rapa + anti-CD25 group. (b) Histology of grafts from (i) anti-CD25 and (iii) isotype control treated mice (haematoxylin & eosin stain, magnification 300×). FoxP3 immunohistochemistry of grafts from (ii) anti-CD25 and (iv) isotype control treated mice (magnification 100×). (c) Morphometric analysis of allografts. Cells stained positive for FoxP3 are shown as percentage of CD3+ allograft-infiltrating cells from anti-CD25 antibody (Rapa + anti-CD25) and isotype control (Rapa + Isotype) treated groups. Minimum of three mice per group. Graph shows mean ± SEM. *P < 0·001 by two-tailed t-test. (d) Graft survival in anti-CD25 antibody (○, mean survival time = 52·2 days, n = 6) and isotype control treated (•: survival time > 100 days, n = 3) recipients. *P < 0·05. Rapa, rapamycin.

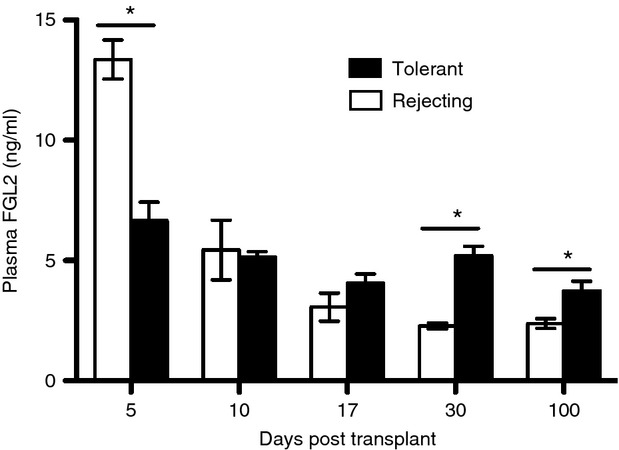

Sustained levels of FGL2 in plasma correlate with allograft tolerance

Based on studies showing that FGL2 is a Treg effector protein, we next examined whether plasma levels of FGL2 might be a useful protein biomarker for tolerance (Fig. 6). At baseline, plasma levels of FGL2 in control non-transplanted mice were low (2·5 ± 0·2 ng/ml, mean ± SEM). At day 5 post transplant, levels of FGL2 were higher in rejecting mice (13·2 ± 1·0 ng/ml) compared with tolerant mice (6·7 ± 0·8 ng/ml) and non-transplanted controls (2·5 ± 0·2 ng/ml). By day 17, levels of FGL2 in rejecting mice returned to baseline, whereas plasma levels of FGL2 in tolerant mice remained persistently elevated. Even at day 100 post transplant, levels of FGL2 remained higher in tolerant mice compared with non-transplanted control mice (3·7 ± 0·3 ng/ml versus 2·5 ± 0·2 ng/ml, P < 0·05) and rapamycin-only treated mice (3·7 ± 0·3 ng/ml versus 2·6 ± 0·2 ng/ml, P < 0·05). Hence, although early levels of FGL2 do not distinguish between rejection and tolerance, at later time-points (> 17 days) levels of FGL2 may be useful to predict tolerance.

Figure 6.

Plasma levels of fibrinogen-like protein 2 (FGL2) after allotransplantation. Plasma levels were measured at different time-points after transplantation in tolerant (▪) and rejecting (□) recipients. n = 3 mice per group at each time-point. Graphs show mean level (ng/ml) ± SEM. *P < 0·05.

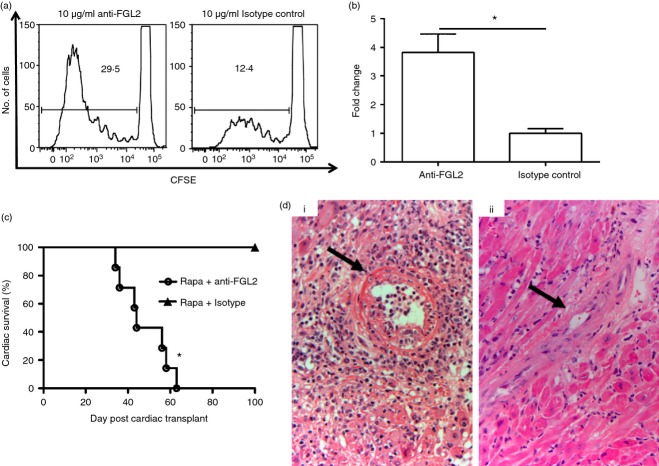

Inhibition of FGL2 reverses the tolerizing effects of rapamycin in vitro and in vivo

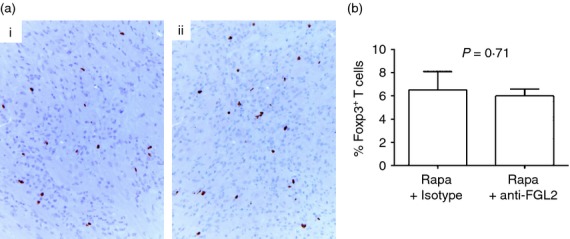

Because plasma levels of FGL2 were persistently elevated in tolerant mice, we examined the effect of FGL2 depletion on tolerance induction. Addition of an anti-FGL2 antibody led to the enhanced proliferation of tolerant SMNC in a one-way MLR in vitro, so supporting the immunosuppressive function of endogenous FGL2 (Fig. 7a,b). Furthermore, treatment of mice with repeated injections of anti-FGL2 antibody prevented the development of tolerance in vivo despite rapamycin treatment. All grafts from recipient mice that were treated with anti-FGL2 antibody were rejected with a mean graft survival of 47·7 days, whereas all grafts survived for > 100 days when recipient mice were treated with an isotype control antibody (Fig. 7c). Histopathology of rejecting grafts confirmed that anti-FGL2 antibody treatment led to acute cellular rejection with vasculitis (Fig. 7d). Unlike treatment with PC61, treatment with anti-FGL2 antibody did not lead to a reduction in the number of Treg cells in the allografts (Fig. 8).

Figure 7.

Inhibition of fibrinogen-like protein 2 (FGL2) reverses the tolerizing effects of rapamycin. (a) Proliferation of splenic mononuclear cells (SMNC) from post-operative day (POD) 30 tolerant mice with either (i) anti-FGL2 or (ii) isotype control by CFSE proliferation. Graphs are representative of three independent experiments. (b) Quantification of CFSE proliferation data. Graph shows proliferation of anti-FGL2-treated SMNC normalized to isotype control-treated SMNC (mean ± SEM). Three independent experiments were performed. *P < 0·05 by two-tailed t-test. (c) Allograft survival in mice following rapamycin treatment and administration of either anti-FGL2 (o: mean survival time = 47·7 days, n = 6) or isotype control (▲: survival time > 100 days, n = 3). *P < 0·05. Mice received an intraperitoneal injection 250 μg of anti-FGL2 antibody or isotype control antibody 2 days before transplantation and on day 0 and 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15 days post-transplantation concurrently with rapamycin. (d) Graft histology following antibody administration. (i) anti-FGL2, black arrow indicates severe vasculitis. (ii) isotype control, black arrow indicates normal appearing blood vessel. (Haematoxylin & eosin stain; magnification 100×).

Figure 8.

Anti-fibrinogen-like protein 2 (FGL2) antibody does not reduce numbers of regulatory T (Treg) cells in allografts. (a) FoxP3 immunohistochemistry of grafts from (i) isotype control and (ii) anti-FGL2 treated mice (magnification 200×). (b) Morphometric analysis of allografts. Cells stained positive for FoxP3 are shown as percentage of CD3+ allograft-infiltrating cells from anti-FGL2 antibody (Rapa + anti-FGL2) (n = 6) and isotype control (Rapa + Isotype) (n = 3) treated groups. Graph shows mean ± SEM. P = 0·71 by two-tailed t-test.

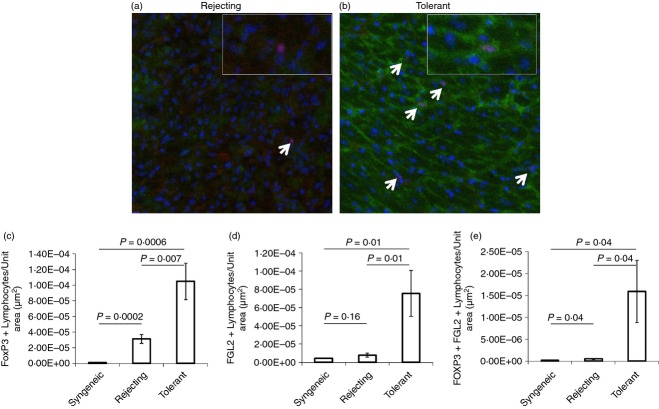

FoxP3+ Treg cells that express FGL2 are enriched in tolerant allografts

To determine whether FoxP3+ Treg cells express FGL2, we co-stained syngeneic, rejecting, and tolerant heart grafts for FoxP3 and FGL2 (Fig. 9a,b). FoxP3 staining was mainly nuclear and co-localized with DAPI staining (Fig. 9a). FGL2 staining was present both in the cell membrane and cytoplasm of positive cells (Fig. 9b). In agreement with data in Fig. 4, grafts from tolerant mice contained greater numbers of FoxP3+ cells compared with rejected allografts and syngeneic grafts (Fig. 9c). Furthermore, grafts from tolerant mice contained greater numbers of FGL2-positive cells than either rejected or syngeneic grafts (Fig. 9d). Of interest, FGL2 and FoxP3 were co-expressed almost exclusively in grafts from tolerant mice, whereas few if any FGL2+ FoxP3+ double-positive cells were seen in rejecting or syngeneic grafts (Fig. 9e). These data strongly support our hypothesis that Treg cells expressing FGL2 are necessary for tolerance induction. Furthermore, these data are supportive of the recent observations that Treg cells are not monomorphic and may express different cytokine profiles.29 Of note, FGL2 staining was not exclusive to the Treg cell compartment; FGL2 staining was also seen in cardiac myocytes and in infiltrating mononuclear cells.

Figure 9.

Co-expression of fibrinogen-like protein 2 (FGL2) and FoxP3 in regulatory T (Treg) cells in tolerant allografts. (a, b) Transplanted hearts were harvested from (a) rejecting mice or from (b) tolerant C3H mice at post-operative day (POD) 100 and subsequently immunostained for FoxP3 (red) and FGL2 (green) (magnification 200×). Nuclei were visualized with DAPI (blue). Tolerant mice had significantly increased numbers of FoxP3+ Treg (white arrow). Whereas FoxP3+ Treg from tolerant mice largely expressed FGL2, FoxP3+ Treg in rejecting mice did not express FGL2. Inset shows a FGL2− Treg in a rejecting allograft and a FGL2+ Treg in a tolerant allograft (magnification 1000×). (c–e) Morphometric analysis of the immunostained sections was performed using a Definiens analysis assessing the (c) number of FoxP3+/μm2, (d) FGL2+/μm2 and (e) FoxP3+ FGL2+/μm2. Cardiac myocytes were excluded from analysis using size exclusion. Lymphocytes were defined based on size of 10 µm or less. The morphometric analysis of heart allografts is from six rejecting mice, seven tolerant mice and three syngeneic mice with four serial sections taken at multiple levels of the heart. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed using a Student's t-test.

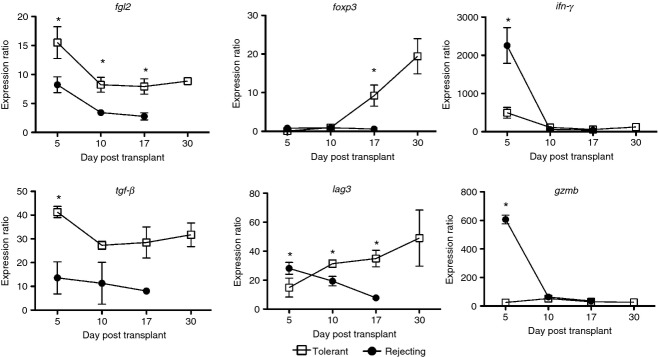

Differentially expressed Treg-related genes in the cardiac allograft correlate with tolerance

The expression level of 22 genes in allografts from tolerant and rejecting mice was assessed by multiplex RT-PCR using GeXP technology (see Supporting information, Fig. S2). Genes were selected in this panel based on their reported association with Treg suppressive activity (see Supporting information, Table S1). Figure 10 shows six genes that were differentially expressed between tolerant and rejecting allografts. Results from the GeXP study were validated by quantitative PCR (data not shown). Four of the genes (foxp3, lag3, tgf-β and fgl2) that were higher in the tolerant allografts have previously been shown to be important for Treg cell functioning in an experimental model of liver transplantation.19 Although these four genes are associated with Treg cells, they displayed different expression kinetics. For example, foxp3 and lag3 rose steadily after transplant in tolerant allografts but had expression levels similar to rejecting allografts at early time-points (day 5). Messenger RNA of fgl2 was elevated early after transplant in tolerant allografts and remained elevated compared with rejecting allografts at all time-points. Expression of ifn-γ and gzmb were markedly higher in rejecting allografts compared with tolerant allografts (Fig. 10). This finding is consistent with the large mononuclear cell infiltrates seen within days in rejecting allografts (Fig. 1b). Interestingly, we did not see this gene expression pattern in SMNC from tolerant or rejecting mice, suggesting that this gene pattern is specific to the graft (data not shown).

Figure 10.

Differentially expressed regulatory T (Treg) -related genes in cardiac allografts serve as putative biomarkers of tolerance. Graphs display differentially expressed genes between tolerant (□) and rejecting (•) grafts from a panel of 22 Treg-related genes (see Supporting information, Table S1) as assessed by multiplex RT-PCR. The expression of a gene was normalized to the housekeeping gene hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase and expression was then calculated as a ratio compared with the expression in non-transplanted hearts. Three allografts were used for each time-point for both tolerant and rejecting groups. Graph shows mean ± SEM. *P < 0·05 versus rejecting group at the same time-point.

Discussion

Although transplantation is a highly effective therapy for patients with end-stage organ failure, the need for immunosuppression limits its long-term success. Hence, new therapies that promote tolerance and novel tools of detecting tolerance are needed to improve long-term patient outcome. In this study, we report that a short course of rapamycin promotes tolerance of fully MHC-mismatched murine cardiac allografts and further showed that tolerant mice maintain in vitro responsiveness to donor antigens consistent with development of peripheral tolerance. We also demonstrated that the novel Treg effector molecule FGL2 is essential to tolerance induction. Finally, we showed that plasma levels of FGL2 as well as allograft expression of a novel gene panel distinguished between tolerant and rejecting grafts.

A number of previous studies have demonstrated that rapamycin promotes tolerance in small animal models of pancreas, skin and heart transplantation.22,30 Although these studies have suggested that Treg cells are important to tolerance induction, the mechanism for rapamycin-induced tolerance has not been fully elucidated. The data presented here demonstrate that rapamycin-induced tolerance is donor-specific as third-party skin grafts were universally rejected in mice that had accepted a BALB/cJ cardiac allograft, whereas skin grafts from BALB/cJ donor mice were accepted. We demonstrated that endotoxin insensitivity was not a pre-requisite for development of graft tolerance as BALB/cJ allografts were accepted in tlr4+/+ C3H/HeOuJ mice treated with rapamycin as well as in mice lacking tlr4 consistent with a previous study that showed that induction and function of Treg cells is independent of Toll-like receptor 4 signalling.31 We also showed that SMNC recovered from tolerant and rejecting mice had equal MLR and CTL responses to third-party alloantigens. In contrast, SMNC from tolerant mice had primary MLR and CTL responses to donor BALB/cJ cells, whereas SMNC from rejecting mice had augmented secondary responses, suggesting that tolerant mice failed to develop immunological memory to donor antigens. In support of this assertion, we demonstrated that tolerant mice failed to develop anti-donor humoral immunity. The finding that donor-specific T cells were present in the peripheral lymphoid compartment suggests that rapamycin-induced tolerance may involve active immune suppression by Treg cells or another suppressive population rather than by deletion of effector cells (central tolerance). Consistent with this observation, we observed that rapamycin-induced tolerance is fragile and that infection with LCMV WE, a virus that produces a self-limited viral infection, led to rejection of tolerant allografts, as has been suggested by other investigators.32–34

A critical role for Treg cells in rapamycin-induced tolerance was demonstrated by the finding that depletion of Treg cells with the anti-CD25 monoclonal antibody (PC61) prevented the establishment of tolerance. Consistent with our findings, previous studies have identified a role for rapamycin in promoting differentiation of Treg cells from naive CD4+ T-cell precursors in vitro as well as in patients who were converted from calcineurin inhibitors to rapamycin.35,36 Interestingly, patients converted to rapamycin also displayed increased numbers of Treg cells within their grafts and immunoregulatory proteogenomic signatures, which might facilitate immunosuppression minimization or withdrawal.35

Donor-specific Treg cells are known to mediate graft tolerance through a number of mechanisms including generation of inhibitory cytokines, induction of apoptosis in effector cells, disruption of effector cell metabolism, and inhibition of DC function.11 FGL2, a member of the fibrinogen superfamily, is a newly described Treg-effector molecule with immunosuppressive properties.15,37 Here, we demonstrated that FGL2 was essential for tolerance induction. Studies performed here demonstrated that tolerant grafts contained high numbers of FGL2+ Treg cells in contrast to rejecting and syngeneic grafts. That FGL2 is critical to tolerance was shown by the observation that depletion of FGL2 in vitro with an anti-FGL2 antibody increased effector cell responses in an MLR assay, and depletion of FGL2 in vivo prevented tolerance leading to rejection of allografts. However, unlike anti-CD25 antibody, use of an anti-FGL2 antibody did not lead to depletion of total numbers of intragraft Treg cells. It has been shown by others that FGL2 is secreted by a number of the members of the Treg family including CD4+ CD25+ FoxP3+ Treg cells as well as CD8+ Treg cells,14,26 and that fgl2 mRNA is more highly expressed in CD4+ CD25+ FoxP3+ Treg cells and in immunosuppressive CD8αα intraepithelial lymphocytes compared with effector CD4+ T cells.16,37,38

The findings described here are consistent with previous studies showing that FoxP3+ Treg cells are not homogeneous but are comprised of distinct subsets with different cytokine profiles.39 For example, expression of CD134 has been shown to augment T helper type 2 cell responses by inducing expression of IL-4, whereas PD-1L has been shown to be important for induced Treg cell stability and suppressive activity.40 A recent observation showed that T-cell immunoglobulin and ITIM (immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif) domain (TIGIT) -expressing Treg cells, which constitute a large percentage of Treg cells, express large amounts of FGL2, which accounts for their immunosuppressive activity.29 The importance of TIGIT+ and FGL2+ Treg cells was shown in models of experimental colitis as well as a model of allergic airway disease.29

A number of groups have shown that FGL2 prevents DC maturation, inhibits T-cell proliferation and skews immune responses to a T helper type 2 phenotype by binding FcγRIIB/III on antigen-presenting cells including B lymphocytes, DC and macrophages.15 The finding that rapamycin-induced tolerance was blocked by either anti-CD25 or anti-FGL2 antibodies and that FGL2 is highly expressed by Treg cells supports the proposed concept that FGL2-producing Treg cells are critical for the development of rapamycin-induced tolerance.

Notably, FGL2 was not expressed exclusively by Treg cells, it was also expressed by cardiac myocytes as previously reported41 and was localized to the cytoplasm and membranes. We have preliminary data that over-expression of fgl2 in the heart does not lead to long-term acceptance of allografts, suggesting that cardiac myocyte expression of FGL2 is not sufficient for tolerance induction. Future studies will use tissue-specific knockouts of fgl2 to determine conclusively if it is the FGL2 produced by Treg cells that is necessary for tolerance induction.

The lack of reliable biomarkers to detect clinical tolerance is a major impediment to its clinical implementation.18 A number of investigators have attempted to use immunological assays as surrogates of tolerance.17–20 More recently, microarray technology has been employed to identify tolerant recipients.42,43 We recently identified a set of genes that have immunoregulatory (Treg-associated) and pro-inflammatory properties and showed that expression of these genes correlated with spontaneous liver allograft acceptance.19 In the present report, we scrutinized in detail this same gene panel. We found that rejecting cardiac allografts were characterized by high expression of the pro-inflammatory genes gzmb and ifn-γ with low expression of foxp3, lag3, tgf-β and fgl2. Tolerant cardiac allografts, on the other hand, were characterized by high expression of immunoregulatory genes foxp3, lag3, tgf-β and fgl2 and low expression of gzmb and ifn-γ, leading to a high immunoregulatory to pro-inflammatory gene expression ratio, similar to what we previously reported in tolerant liver allografts.19 Four immunoregulatory genes (foxp3, lag3, tgf-β and fgl2) with high expression in tolerant cardiac allografts displayed distinct kinetics. Both tgf-β and fgl2 were elevated at the earliest time-points after transplant in tolerant allografts, suggesting that tgf-β and fgl2 may be important in induction of tolerance. Although the mRNA expression levels of foxp3 and lag3 were similar in tolerant and rejecting allografts early after transplantation, expression of both genes increased significantly in tolerant allografts at later time-points, suggesting that these genes may be critical for maintenance of tolerance. FoxP3 is a master regulator of the Treg cell phenotype so it is not surprising that expression of the foxp3 gene increased in tolerant allografts.27,44 Lymphocyte activating gene 3 is a Treg effector protein that inhibits DC maturation,9 which has been proposed to be important in transplant tolerance.45 We did not find differences in gene expression of IL-10 between rejecting and tolerant allografts and so this gene was not included in our data set (data not shown). Although the same gene panel was studied in SMNC from tolerant and rejecting recipients, the same gene signatures were not found, suggesting that monitoring expression of these genes within the allograft may be required for assessing graft rejection and tolerance. Given that heart biopsies are routinely performed post transplant to screen for graft rejection, this biomarker gene panel may be easily translatable to the clinic as an additional tool to monitor for tolerance.

We also examined the utility of measurement of plasma levels of FGL2 using a sensitive bioassay established in our laboratory.46 Although plasma levels of FGL2 were statistically higher in the tolerant grafts at later time-points, marked increases in the levels of FGL2 in the plasma of mice during acute rejection were also observed. The increase in FGL2 was coincident with evidence of severe cell-mediated rejection and so could be an attempt by the host to control graft injury. At later time-points, levels of FGL2 returned to baseline in these rejecting mice. In contrast, levels of FGL2 remained elevated in the plasma of mice that had developed graft tolerance even at 100 days post transplant. Hence, the findings suggest that plasma levels of FGL2 may not discriminate between tolerance and rejection early post transplant. However, plasma levels of FGL2 may have the ability to predict tolerance at later time-points. Whether these findings have relevance to human clinical transplantation remains to be determined.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that Treg cells and FGL2 are necessary for rapamycin-induced tolerance in a murine cardiac allograft model. Tolerant allografts were identified by a high immunoregulatory to pro-inflammatory gene expression ratio distinguishing them from rejecting allografts. Future studies are needed to determine if molecular therapies based on FGL2 can be used to achieve tolerance and if our gene panel and plasma levels of FGL2 can identify tolerant recipients in the setting of heart transplantation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Beckman Coulter for supplying reagents and technical assistance with the GeXP studies. This work was supported by the Heart and Stroke Foundation (Ontario, Canada) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). AC is supported by a postdoctoral award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation and CIHR Training Program in Regenerative Medicine. We also thank the STARR facility at the MARS Facility (Toronto, Ontario, Canada) for performing the co-localization staining and analysis of FoxP3 and FGL2-positive cells. PU, WS, AC, JW, AZ, WH, RK, AA, OA and HS performed experiments in this paper. PU, WS, AC, IS, MJP, OA, DG and GL designed the experiments. PU, WS, AC, RK, HR, DG and GL wrote the paper.

Glossary

- DC

dendritic cell

- DSA

donor-specific antibody

- FGL2

fibrinogen-like protein 2

- FoxP3

forkhead box P3

- IL-2

interleukin-2

- LCMV

lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus

- POD

post-operative day

- SMNC

splenic mononuclear cell

- Rapa

rapamycin

- TIGIT

T-cell immunoreceptor with immunoglobulin and ITIM domains

- Treg

regulatory T

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Figure S1. Absolute numbers of regulatory T (Treg) cells are increased in spleens from tolerant mice. Absolute numbers of splenic FoxP3+ cells are shown from non-transplanted (Non-Tx), post-operative day (POD) 30 rejecting, POD 30 tolerant, rapamycin-only non-transplanted (Rapa only), and POD 30 syngeneic C3H/HeJ recipients. Graph includes data from three or four mice per group (mean ± SEM). *P < 0·05 versus Non-Tx, Rapa only, and syngeneic recipients. **P < 0·05 tolerant versus rejecting mice.

Figure S2. Graphs of all 22 genes in the GeXP RT-PCR assay. Graphs show differential expression of genes in tolerant (□) and rejecting (•) allografts. The expression of each gene was normalized to the housekeeping gene HPRT. In the graphs, gene expression is shown as a ratio compared with the expression of the same gene in non-transplanted control hearts. Three allografts were used for each time-point for both tolerant and rejecting groups. Graph shows mean ± SEM. *P < 0·05 versus no treatment group at the same time-point.

Table S1. Panel of genes in the GEXP RT-PCR assay. 1c to 5c are housekeeping genes and 6c is an internal control. Table lists gene ID, gene name, and gene description.

References

- 1.Lechler RI, Sykes M, Thomson AW, Turka LA. Organ transplantation – how much of the promise has been realized? Nat Med. 2005;11:605–13. doi: 10.1038/nm1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Battaglia M, Stabilini A, Migliavacca B, Horejs-Hoeck J, Kaupper T, Roncarolo MG. Rapamycin promotes expansion of functional CD4+ CD25+ FOXP3+ regulatory T cells of both healthy subjects and type 1 diabetic patients. J Immunol. 2006;177:8338–47. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.12.8338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Battaglia M, Stabilini A, Roncarolo MG. Rapamycin selectively expands CD4+ CD25+ FoxP3+ regulatory T cells. Blood. 2005;105:4743–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomson AW, Turnquist HR, Raimondi G. Immunoregulatory functions of mTOR inhibition. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:324–37. doi: 10.1038/nri2546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dai Z, Li Q, Wang Y, Gao G, Diggs LS, Tellides G, Lakkis FG. CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells suppress allograft rejection mediated by memory CD8+ T cells via a CD30-dependent mechanism. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:310–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI19727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xia G, He J, Zhang Z, Leventhal JR. Targeting acute allograft rejection by immunotherapy with ex vivo-expanded natural CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells. Transplantation. 2006;82:1749–55. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000250731.44913.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Powell JD, Pollizzi KN, Heikamp EB, Horton MR. Regulation of immune responses by mTOR. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:39–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strauss L, Czystowska M, Szajnik M, Mandapathil M, Whiteside TL. Differential responses of human regulatory T cells (Treg) and effector T cells to rapamycin. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5994. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang CT, Workman CJ, Flies D, et al. Role of LAG-3 in regulatory T cells. Immunity. 2004;21:503–13. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Read S, Malmstrom V, Powrie F. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 plays an essential role in the function of CD25+ CD4+ regulatory cells that control intestinal inflammation. J Exp Med. 2000;192:295–302. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vignali DA, Collison LW, Workman CJ. How regulatory T cells work. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:523–32. doi: 10.1038/nri2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gondek DC, Lu LF, Quezada SA, Sakaguchi S, Noelle RJ. Cutting edge: contact-mediated suppression by CD4+ CD25+ regulatory cells involves a granzyme B-dependent, perforin-independent mechanism. J Immunol. 2005;174:1783–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pandiyan P, Zheng L, Ishihara S, Reed J, Lenardo MJ. CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells induce cytokine deprivation-mediated apoptosis of effector CD4+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1353–62. doi: 10.1038/ni1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li XL, Menoret S, Bezie S, et al. Mechanism and localization of CD8 regulatory T cells in a heart transplant model of tolerance. J Immunol. 2010;185:823–33. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu H, Shalev I, Manuel J, et al. The FGL2-FcγRIIB pathway: a novel mechanism leading to immunosuppression. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:3114–26. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shalev I, Liu H, Koscik C, et al. Targeted deletion of fgl2 leads to impaired regulatory T cell activity and development of autoimmune glomerulonephritis. J Immunol. 2008;180:249–60. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurian SM, Heilman R, Mondala TS, et al. Biomarkers for early and late stage chronic allograft nephropathy by proteogenomic profiling of peripheral blood. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turka LA, Lechler RI. Towards the identification of biomarkers of transplantation tolerance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:521–6. doi: 10.1038/nri2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xie L, Ichimaru N, Morita M, et al. Identification of a novel biomarker gene set with sensitivity and specificity for distinguishing between allograft rejection and tolerance. Liver Transpl. 2012;18:444–54. doi: 10.1002/lt.22480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deng MC, Eisen HJ, Mehra MR, et al. Noninvasive discrimination of rejection in cardiac allograft recipients using gene expression profiling. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:150–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corry RJ, Winn HJ, Russell PS. Primarily vascularized allografts of hearts in mice. The role of H-2D, H-2K, and non-H-2 antigens in rejection. Transplantation. 1973;16:343–50. doi: 10.1097/00007890-197310000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y, Li XC, Zheng XX, Wells AD, Turka LA, Strom TB. Blocking both signal 1 and signal 2 of T-cell activation prevents apoptosis of alloreactive T cells and induction of peripheral allograft tolerance. Nat Med. 1999;5:1298–302. doi: 10.1038/15256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braun M, Kirsten R, Rupp NJ, Moch H, Fend F, Wernert N, Kristiansen G, Perner S. Quantification of protein expression in cells and cellular subcompartments on immunohistochemical sections using a computer supported image analysis system. Histol Histopathol. 2013;28:605–10. doi: 10.14670/HH-28.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawrence BP. Measuring the activity of cytolytic lymphocytes. Curr Protoc Toxicol. 2005 doi: 10.1002/0471140856.tx1806s22. Chapter 18:Unit18 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khattar R, Luft O, Yavorska N, et al. Targeted deletion of FGL2 leads to increased early viral replication and enhanced adaptive immunity in a murine model of acute viral hepatitis caused by LCMV WE. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e72309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shalev I, Wong KM, Foerster K, et al. The novel CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cell effector molecule fibrinogen-like protein 2 contributes to the outcome of murine fulminant viral hepatitis. Hepatology. 2009;49:387–97. doi: 10.1002/hep.22684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fontenot JD, Rasmussen JP, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. A function for interleukin 2 in Foxp3-expressing regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1142–51. doi: 10.1038/ni1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, et al. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science. 1998;282:2085–8. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joller N, Lozano E, Burkett PR, et al. Treg cells expressing the coinhibitory molecule TIGIT selectively inhibit proinflammatory Th1 and Th17 cell responses. Immunity. 2014;40:569–81. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gagliani N, Gregori S, Jofra T, et al. Rapamycin combined with anti-CD45RB mAb and IL-10 or with G-CSF induces tolerance in a stringent mouse model of islet transplantation. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e28434. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhai Y, Meng L, Gao F, Wang Y, Busuttil RW, Kupiec-Weglinski JW. CD4+ T regulatory cell induction and function in transplant recipients after CD154 blockade is TLR4 independent. J Immunol. 2006;176:5988–94. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.5988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pascher A, Proesch S, Pratschke J, et al. Rat cytomegalovirus infection interferes with anti-CD4 mAb-(RIB 5/2) mediated tolerance and induces chronic allograft damage. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:2035–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stapler D, Lee ED, Selvaraj SA, Evans AG, Kean LS, Speck SH, Larsen CP, Gangappa S. Expansion of effector memory TCR Vbeta4+ CD8+ T cells is associated with latent infection-mediated resistance to transplantation tolerance. J Immunol. 2008;180:3190–200. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chong AS, Alegre ML. The impact of infection and tissue damage in solid-organ transplantation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:459–71. doi: 10.1038/nri3215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levitsky J, Mathew JM, Abecassis M, et al. Systemic immunoregulatory and proteogenomic effects of tacrolimus to sirolimus conversion in liver transplant recipients. Hepatology. 2013;57:239–48. doi: 10.1002/hep.25579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strauss L, Whiteside TL, Knights A, Bergmann C, Knuth A, Zippelius A. Selective survival of naturally occurring human CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells cultured with rapamycin. J Immunol. 2007;178:320–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koyama T, Hall LR, Haser WG, Tonegawa S, Saito H. Structure of a cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-specific gene shows a strong homology to fibrinogen β and γ chains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:1609–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.6.1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marazzi S, Blum S, Hartmann R, et al. Characterization of human fibroleukin, a fibrinogen-like protein secreted by T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1998;161:138–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chaudhry A, Rudra D, Treuting P, Samstein RM, Liang Y, Kas A, Rudensky AY. CD4+ regulatory T cells control TH17 responses in a Stat3-dependent manner. Science. 2009;326:986–91. doi: 10.1126/science.1172702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Francisco LM, Salinas VH, Brown KE, Vanguri VK, Freeman GJ, Kuchroo VK, Sharpe AH. PD-L1 regulates the development, maintenance, and function of induced regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206:3015–29. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mu J, Qu D, Bartczak A, et al. Fgl2 deficiency causes neonatal death and cardiac dysfunction during embryonic and postnatal development in mice. Physiol Genomics. 2007;31:53–62. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00026.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sagoo P, Perucha E, Sawitzki B, et al. Development of a cross-platform biomarker signature to detect renal transplant tolerance in humans. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1848–61. doi: 10.1172/JCI39922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lande JD, Patil J, Li N, Berryman TR, King RA, Hertz MI. Novel insights into lung transplant rejection by microarray analysis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4:44–51. doi: 10.1513/pats.200605-110JG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zheng Y, Josefowicz SZ, Kas A, Chu TT, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Genome-wide analysis of Foxp3 target genes in developing and mature regulatory T cells. Nature. 2007;445:936–40. doi: 10.1038/nature05563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morelli AE, Thomson AW. Tolerogenic dendritic cells and the quest for transplant tolerance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:610–21. doi: 10.1038/nri2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Foerster K, Helmy A, Zhu Y, et al. The novel immunoregulatory molecule FGL2: a potential biomarker for severity of chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol. 2010;53:608–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Absolute numbers of regulatory T (Treg) cells are increased in spleens from tolerant mice. Absolute numbers of splenic FoxP3+ cells are shown from non-transplanted (Non-Tx), post-operative day (POD) 30 rejecting, POD 30 tolerant, rapamycin-only non-transplanted (Rapa only), and POD 30 syngeneic C3H/HeJ recipients. Graph includes data from three or four mice per group (mean ± SEM). *P < 0·05 versus Non-Tx, Rapa only, and syngeneic recipients. **P < 0·05 tolerant versus rejecting mice.

Figure S2. Graphs of all 22 genes in the GeXP RT-PCR assay. Graphs show differential expression of genes in tolerant (□) and rejecting (•) allografts. The expression of each gene was normalized to the housekeeping gene HPRT. In the graphs, gene expression is shown as a ratio compared with the expression of the same gene in non-transplanted control hearts. Three allografts were used for each time-point for both tolerant and rejecting groups. Graph shows mean ± SEM. *P < 0·05 versus no treatment group at the same time-point.

Table S1. Panel of genes in the GEXP RT-PCR assay. 1c to 5c are housekeeping genes and 6c is an internal control. Table lists gene ID, gene name, and gene description.