Abstract

Idiopathic membranous nephropathy (MN) is one common cause of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome in adults; 25% of MN patients proceed to end-stage renal disease. In adults, membranous nephropathy is a lead cause of nephrotic syndrome, with about 75% of the cases idiopathic. Secondary causes include autoimmune disease, infection, drugs and malignancy. Three hypotheses about pathogenesis have surfaced: preformed immune complex, in situ immune complex formation, and auto-antibody against podocyte membrane antigen. Pathogenesis does involve immune complex formation with later deposition in sub-epithelial sites, but definite mechanism is still unknown. Several genes were recently proven associated with primary membranous nephropathy in Taiwan: IL-6, NPHS1, TLR-4, TLR-9, STAT4, and MYH9 . These may provide a useful tool for diagnosis and prognosis. This article reviews epidemiology and lends new information on KIRREL2 (rs443186 and rs447707) polymorphisms as underlying causes of MN; polymorphisms revealed by this study warrant further investigation.

Keywords: Membranous glomerulonephritis (MN), Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), Haplotype

1. Introduction

Idiopathic membranous nephropathy (MN), common cause of nephrotic syndrome, accounts for about 40% of adult cases with clinical presentation of severe proteinuria, edema, hypoalbuminuria and hyperlipidemia [1]. Its characteristics include basement membrane thickening and subepithelial immune deposits without cellular proliferation or infiltration [2]. Prior study suggested MN as causing chronic kidney disease (CKD) and as final result of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [3]. Therapy such as nonspecific antiproteinuric measures and immunosuppressive drugs yielded disappointing results, heightening interest in new therapeutic targets [4]. Taiwan has the highest prevalence of ESRD worldwide; MN may be one cause [5-7]. Genetic and environmental factors may contribute to progression and renal fibrosis in most renal diseases. Identifying genetic mechanisms related to high incidence of MN is crucial to current situation in Taiwan. This review highlights candidate genes studied over these past three years in Taiwan and discusses their implications in MN pathogenesis.

2. Genetic association studies on MN over three years in Taiwan

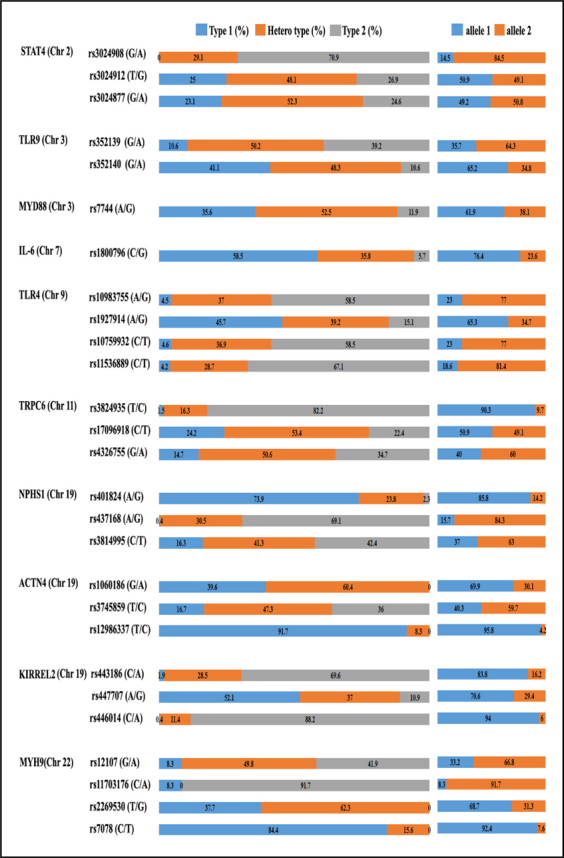

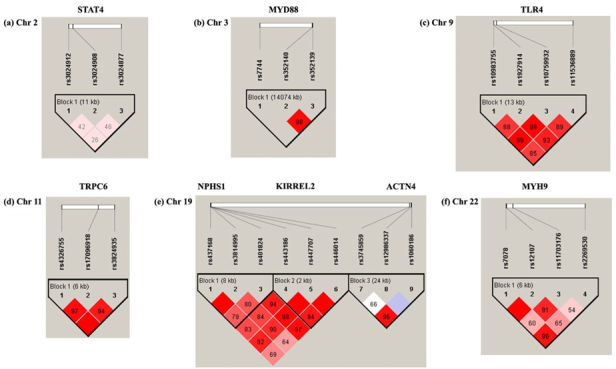

Table 1 displays characteristics of genetic polymorphisms in MN research across three years in Taiwan. Genes were discussed previously, all involved in pathogenesis: STAT4 , TLR9 , IL-6 , TLR4 , TRPC6 , NPHS1 , and MYH9 [8-14]. Our new information about polymorphisms on MYD88, ACTN4, and KIRREL2 relates to MN susceptibility. Figure 1 shows distributions of genotypic and allelic frequencies of 27 polymorphisms on 10 genes in normal population in Taiwan. We observed rs3024908 polymorphism on STAT4 gene without G/G genotype; rs1060186 and rs12986337 on ACTN4 without A/A and C/C genotype, respectively; and rs2269530 on MYH9 without G/G genotype in normal population. We assessed genotypic and allelic frequencies of these in MN cases and controls (Table 2) to find strong links between MN and rs3024908 on STAT4 gene, rs352139 on TLR9 , rs1800796 on IL-6 , rs10983755 and rs1927914 on TLR4 , rs437168 on NPHS1 , and rs443186 on KIRREL2. LD and Haplotype block structure were estimated via 27 polymorphisms on 10 MN-linked genes (Fig. 2). According to chromosome type, structures appeared as (a) Chr2 (b) Chr3 (c) Chr9 (d) Chr11 (e) Chr19 (f) Chr22. Color scheme of linkage disequilibrium (LD) map is based on standard D’/LOD option in Haploview software, LD blocks calculated by CI method.

Table 1.

Characteristics of polymorphisms in study of idiopathic membranous nephropathy over these past three years in Taiwan.

| Gene name | SNP database ID | Location | Variation Legend | Referneces |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAT4 | rs3024908 | 2:191894141 | 3’UTR(G/T) | Chen et al., 2011 [8] |

| rs3024912 | 2:191893087 | 3’UTR(A/G) | ||

| rs3024877 | 2:191904889 | intro n 15(A/G) | ||

| TLR9 | rs352140 | 3:52256697 | exon 2(C/T) | Chen et al., 2013 [9] |

| rs352139 | 3:52258372 | intro n 1 (C/T) | ||

| MYD88* | rs7744 | 3:38184021 | 3’UTR(A/G) | |

| IL-6 | rs1800796 | 7:22766246 | C-572G | Chen et al., 2010 [10] |

| TLR4 | rs10983755 | 9:120464670 | 5’UTR(A/G) | Chen et al., 2010 [11] |

| rs1927914 | 9:120464725 | 5’UTR(A/G) | ||

| rs10759932 | 9:120465144 | 5’UTR(C/T) | ||

| rs11536889 | 9:120478131 | 3’UTR(C/G) | ||

| TRPC6 | rs3824935 | 11:101456002 | 3’UTR(C/T) | Chen et al., 2010 [12] |

| rs17096918 | 11:101453995 | intro n 1 (C/T) | ||

| rs4326755 | 11:101449358 | intron 1 (A/G) | ||

| NPHS1 | rs401824 | 19:36342909 | 5’UTR(A/G) | Lo et al, 2010 [13] |

| rs437168 | 19:36334419 | exon 3(C/T) | ||

| rs3814995 | 19:36342212 | exon 17(A/G) | ||

| ACHT4* | rs1060186 | 19:39221295 | 3’TJTR(A/G) | |

| rs3745859 | 19:39196745 | exon 5(C/T) | ||

| rsl2986337 | 19:39215172 | exon 16 (C/T) | ||

| KIRREL2* | rs443186 | 19:36345951 | 5’UTR(A/C) | |

| rs447707 | 19:36347400 | 5’UTR(A/G) | ||

| rs446014 | 19:36348078 | exon 1(AJC) | ||

| MYH9 | rs12107 | 22:36677982 | 3’UTR(A/G) | Chen et al., 2013 [14] |

| rs11703176 | 22:36678476 | 3’UTR(A/G) | ||

| rs2269530 | 22:36684358 | 3’UTR(A/C) | ||

| rs7078 | 22:36677914 | exon 34(T/G) |

*: Unpublished new results by authors

Fig. 1.

Distributions of genotypic and allelic frequencies of polymorphisms in normal population in Taiwan.

Table 2.

Genotypic and allelic frequencies of polymorphisms in MGN patients versus controls.

| Genotype frequency | Allele frequency | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | db SNP ID | Patient with MGN (%) | Control (%) | p value | Patient with MGN (%) | Central (%) | p value | ||||||

| 1 | heter | 2 | 1 | heter | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| STAT4 (Chr2) | rs3024903 (G/A) | 4(2.9) | 33(24.1) | 100(73) | 0(0) | 77(29.1) | 188(70.9) | 0.014 * | 41(15) | 233(85) | 77(14.5) | 453(84.5) | 0.869 |

| rs3024912 (T/G) | 31(22,8) | 7X55.1) | 30(22.1) | 66(25) | 127(48.1) | 71(26.9) | 0,388 | 135(49.6) | 137(50.4) | 269(50.9) | 259(49.1) | 0.725 | |

| rs3024877 (G/A) | 36 (26.1) | 70(50.7) | 32(23.2) | 61(23.1) | 138(52J) | 65(246) | 0.797 | 142(51.4) | 134(43.6) | 260(49.2) | 263(50.8) | 0.552 | |

| TLR9 (Chr3) | rs352139 (G/A) | 16 (11.9) | 51 (38.1) | 67(50.0) | 28 (10 6) | 133 (50 2) | 104(393) | 0.067 * | 83(31.0) | 185 (69D) | 189 (35.7) | 341 (64.3) | 0.187 |

| rs35214Q (G/A) | 70(523 | 48 (35.8) | 16(11.9) | 108(41.1) | 127 (48,3) | 28(10.6) | 0J3J7 | 188 (70.1) | 80(29.9) | 343 (65.2) | 183 (34.8) | 0.162 | |

| MYD88 (Chr3) | rs7744(A/G) | 44(331) | 75(56.4) | 14(10.5) | 93(35.6) | 137(52.5) | 31(115) | 0758 | 163(613) | 103(38.7) | 323(61.9) | 199(38.1) | 0.870 |

| IL6 (Chr7) | rs1800796 (C/G) | 84(79.2) | 20 (18.9) | 2(1-9) | 155(585) | 95 (35.8) | 15(5.7) | < 0.001 * | 188 (88.7) | 24(11.3) | 405 (76.4) | 125(23.6) | < 0.1101 * |

| TLR.4(Chi9) | rs10983755 (A/G) | 3(6.0) | 75 (56.0) | 51 (38.1) | 12 (4 J) | 98 (37.0) | 155 (585) | < 0.001 * | 91 (34.0) | 177 (66.8) | 122 (23.D) | 408(77.0) | 0.001 * |

| rs1S27914(A/G) | 44(32.8) | 67 (50.0) | 33(17.2) | 121 (45 7) | 104(392) | 40(15.1) | 0.045 * | 155 (57.8) | 113(42.2) | 346 (65.3) | 184(34.7) | 0.039 * | |

| rs10759932 (C/T) | 8(6.0) | 56(41.8) | 70(52.2) | 12(4.6) | 97(36 9) | 154(58 6) | 0.465 | 72(26.9) | 196(73.1) | 121(23.0) | 405(77.0) | 0.230 | |

| rs11536889 (C/T) | 6(4.5) | 45 (33.8) | 82(61.7) | 11(4.2) | 75 (28.7) | 175 (67.0) | 0.559 | 57(21.4) | 209 (78 j6) | 97(186) | 425(81.4) | 0.341 | |

| TRPC6 (Chrll) | rs3824935 (T/C) | 0(0) | 16(11.9) | 118(88.1) | 4(1.5) | 43(16 J) | 216(82.1) | 0.126 | 252 (94.0) | 16(6.0) | 475(90.3) | 52(97) | 0.063 |

| rs17096918(C/T) | 32(23.9) | 74(55,2) | 28(20.9) | 64(24.2) | 141(53.4) | 59 (22.3) | 0.930 | 138 (51.5) | 130 (48.5) | 269(50.9) | 259(49.1) | 0.834 | |

| rs432S755(G/A) | 25 (18.7) | 74(55.2) | 35(26.1) | 39 (147) | 134(50 6) | 92 (34.7) | 0.192 | 124(463) | 144(53.7) | 212(40.0) | 318 (60.0) | 0.090 | |

| NPHS1 (ChrlS) | rs401824(A/G) | 113(81.9) | 24(174) | 1(07) | 196(74.0) | 63(23,8) | 6(2.3) | 0.158 | 250(90.6) | 26(9.4) | 455(35.8) | 75(142) | 0.054 |

| rs437168(A/G) | 0(0) | 25 (18.5) | 110(81.5) | 1 (0.4) | 81 (30.6) | 183 (69 1) | 0.026 * | 25(9.3) | 245 (90.7) | 83(15.7) | 447 (84.3) | 0.012 * | |

| rs3814995 (C/T) | 18(136) | 51(3Sj6) | 63(47,7) | 42(16.3) | 106(41.2) | 109(42 4) | 0372 | 87(33.0) | 177(67 0) | 190(37.0) | 324(63,0) | 0.269 | |

| ACTN4(Chrl9) | rs10601S6 (G/A) | 55(401) | 32(599) | 0 | 105(39.6) | 160(60.4) | 0 | 0919 | 192(70) | 82(30) | 370(69.9) | 160(30.1) | 0.939 |

| rs3745859 (T/C) | 18(13.3) | 73(53.7) | 45(33) | 44(16.7) | 125(47.3) | 95(36) | 0.444 | 109(40) | 163(60) | 213(403) | 315(59.7) | 0.942 | |

| rs12986337 (T/C) | 125(92.6) | 10(7.4) | 0 | 242(91.7) | 22(83) | 0 | 0747 | 260(96.3) | 10(3.7) | 506(95.8) | 22(4.2) | 0.752 | |

| KIKREL2 (Chr 19) | rs443186 (C/A) | 0(0) | 26(19.1) | 110(80.9) | 5(1.9) | 75 (28.5) | 183 (69.6) | 0.015 * | 246(90.4) | 26 (9.6) | 441 (33.8) | 85 (16.2) | 0.011 * |

| rs447707 (A/G) | 83(619) | 43 (32.1) | 8(6.0) | 138(52.1) | 98 (37.0) | 29(10.9) | 0.103 | 209(78.0) | 59 (22.0) | 374(70.6) | 156(294) | 0.026 * | |

| rs446014(C/A) | 0(0) | 15(11.2) | 119(88.8) | 1 (0.4) | 30(11.4) | 233 (88.3) | 0872 | 253 (94.4) | 15(5.6) | 496(94.0) | 32 (6.0) | 0.793 | |

| MYH9(Chr 22) | rs12107 (G/A) | 9(6.7) | 53(39.3) | 73(54) | 22(8.3) | 132(49.8) | 111(41,9) | 0.069 | 71(26.3) | 199(73.7) | 176(33.2) | 354(66.8) | 0.045 * |

| rs11703176 (C/A) | 9(6.7) | 0(0) | 125(93.3) | 22(83) | 0(0) | 243(91.7) | 0J76 | 18(6.7) | 250(93.3) | 44(3.3) | 486(91,7) | 0.429 | |

| rs2269530 (T/G) | 51(38.1) | 83(61.9) | 0(0) | 100(37.7) | 165(62.3) | 0(0) | 0.950 | 185(69) | 83(31) | 36X68.7) | 165(31.3) | 0.963 | |

| rs7078 (C/T) | 115(85.8) | 19(143) | 0(0) | 221(84.4) | 42(15,6) | 0(0) | 0.640 | 249(92.9) | 19(7.1) | 434(924) | 42(7.6) | 0.654 | |

Fig. 2.

LD and haplotype block structure of genes associated with MN by different chromosomes: (a) Chr2 (b) Chr3 (c) Chr9 (d) Chr11 (e) Chr19 (f) Chr22. Color scheme of linkage disequilibrium LD map is based on standard D’/LOD option in Haploview software, LD blocks calculated based on CI method.

3. Transducer and Activator of Transcription 4 (STAT4)

The signal transducer and activator of transcription 4 (STAT4 ) gene, located on chromosome 2q32.2-32.3, encodes a transcription factor essential to inflammation in various immune-mediated diseases [15]. STAT4 plays a key role in regulating immune response by transmitting signals activated in response to cytokines like Type 1 IFN, IL-12, and IL-23 [16]. STAT4 is vital for IL-12 inducing naïve CD4+ T differentiation of into Th1 cells that drive chronic inflammation by secreting high levels of cytokines like IFN-γ and TNF-α [17]. STAT4 haplotype characterized by rs7574865 exhibited strong linkage with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and autoimmune disease: e.g., systemic sclerosis, Sjögren’s syndrome, Type 1 diabetes [18-22]. SY Chen et al. (2011) reported significant difference in genotype frequency at rs3024908 SNP in MN patients versus controls (p = 0.014); those with GG genotype at rs3024912 SNP face higher risk of kidney failure in MN cases (adjusted odds ratio [OR] = 3.255; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.155-9.176, p = 0.026) [8].

4. Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR-9)

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) play a central role in response of both the innate and adaptive immune system to microbial ligands [23]. Glomerular disease is triggered or exacerbated by microbes that activate the immune system by Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligation [24-25]. Exaggerated TLR activation associates with ischemic kidney damage, acute kidney injury, end-stage renal failure, acute renal transplant rejection, acute tubulointerstitial nephritis and delayed allograft function [25]. TLR9 is implicated in initiation and progression of kidney disease (human and experimental): e.g., crescetic, lupus nephritis, glomerulonephritis, IgA nephropathy [26-28]. YT Chen et al. (2013) cited AA genotype at rs352139 SNP or GG at rs352140 SNP indicating higher risk of MN (odds ratio [OR]=1.55; 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.02–2.35, at rs352139 SNP; OR=1.57; 95% CI=1.03–2.39, at rs352140 SNP); A-G haplotype raised susceptibility to decreased creatinine clearance rate and serious tubule-interstitial fibrosis [9].

5. Interleukin-6 (IL-6)

Mounting evidence hints pro-inflammatory cytokines like tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-1 (IL-I), playing a crucial role in lupus nephritis and proliferative IC glomerulonephritis [29-31]. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is also implicated in manifestations of nephropathy [32-33]. Urinary IL-6 stimulated proliferation of rat mesangial cells yielding IL-6 in vitro [32]. Urinary IL-6 has been identified as a marker of renal IL-6 production [34]: high levels of it arise in 30-50% of IgA nephropathy cases [32-33]. IL-6 may thus act as an autocrine growth factor in the mesangium and dysregulated IL-6 production in mesangial proliferation linked with glomerulonephritis. Among Taiwan’s Han Chinese, data show starkly different genotype and allele frequency at IL-6 C-572G SNP in MN cases versus controls (p=1.6E-04 and 1.7E-04, respectively). People with C allele or with CC genotype at IL-6 C-572G SNP show higher risk of MN (OR=2.42 and 2.71; 95% CI=1.51-3.87 and 1.60-4.60, respectively) [10].

6. Toll-like receptors 4 (TLR-4)

Toll-like receptors (TLRs), a key element of human innate immune response, up-regulate proinflammatory cytokines and co-stimulatory molecules as a first line host defence [35]. TLRs are cited as key components of pathogen-recognition process mediating inflammatory response [36]. TLR4 interacts with ligands such as heat-shock proteins [37]; TLR4 polymorphisms reportedly link with inflammatory disease and/or cancer: e.g., Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, cervical cancer [38-40]. Recent report indicated significant difference of TLR4 gene rs10983755 A/G (p < 0.001) and rs1927914 A/G (p < 0.05) polymorphisms between controls and MN patients. Distributions of rs10759932 C/T and rs11536889 C/T polymorphisms differed significantly. Higher triglyceride level arose in non-GG versus GG group. Genotype of non-AA had a far higher proteinuria ratio than AA group [11].

7. Nephrin (NPHS1)

This signaling adhesion protein is believed to play a vital role in modulating renal function [41]. Research on nephrin function initially focused on interaction of slit diaphragm structural components (SD) [42]. Recent research demonstrates nephrin as involved in signal processes critical to podocyte function, survival and differentiation [43]. Polymorphisms in NPHS1 demonstratrably play a pivotal role in progression of renal failure [44]. Mutations of NPHS1 or NPHS2 reportedly associate with severe nephrotic syndrome that progresses to end-stage renal failure in children [45]. R229Q, a NPHS1 variant, meant 20-40% higher risk of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in European populations [46]. Lo et al., 2010 reported significant difference in genotype frequency distribution of rs437168 polymorphism between MN patients and controls. Their results also showed frequency of G allele significantly higher in the MN group; stratified analysis linked high disease progression in AA genotype of rs401824 and GG genotype of rs437168 patients with low rate of remission [13].

8. Myosin Heavy Chain 9 (MYH9)

This gene, expressed in glomerular podocytes and mesangial cells, encodes nonmuscle myosin IIA [47, 48]. Currently, 44 of it mutations have been reported [49], possibly involving either N-terminal motor or C-terminal tail domain of MYH9 gene encoding for the heavy chain of nonmuscle myosin-IIA. The MYH9 haplotypes show replicated association with risk and protection [50, 51]. They are proven as associated with kidney disease in African Americans and European Americans [52, 53]; MYH9 also affects kidney function in Europeans [54]. Results portend statistically significant difference in allele frequency distribution at rs12107 between MN cases and controls (p = 0.04). Persons with AA genotype at rs12107 SNP who contract MN face higher risk of kidney failure than other MN cases (adjusted odds ratio: 1.63; 95% confidence interval: 1.08-2.48, p = 0.02). C-A haplotype is susceptible to MN [14].

9. Kin of IRRE Like 2 (Drosophila) (KIRREL2)

This protein exhibits sequence resembling that of several cell adhesion proteins: e.g., Drosophila RST (irregular chiasm C-roughest), mammalian KIRREL (akin to irregular chiasm C-roughest; NEPH1), NPHS1 (nephrin). The former, a complex gene with mutations originally assigned to separate loci, has alleles originally assigned to irregular chiasm locus, affecting axonal migration in the optic lobes. Other alleles, originally assigned to the roughest locus, link with reduced apoptosis in the retina, inducing roughened appearance of the compound eye [55] and [56]. The mammalian KIRREL/NEPH1 and NPHS1 genes both encode components of the glomerular slit diaphragm in kidneys [57], [58] and [59]. We noted significant difference in genotype frequency distribution of rs443186 polymorphism between MN patients and controls. Data showed frequency of C allele at rs443186 and A allele at rs447707 definitely higher in the MN group. Data indicate individuals with AA genotype at rs443186 SNP face higher risk of MN (Table 2).

10. Conclusion

Genetic susceptibility plays a major role in pathogenesis [60]. Research efforts, including GWASs, have been invested worldwide to identify susceptibility genes for several diseases. GWASs are considered as a powerful and promising approach [61]. Candidate gene approach along with an appropriate analysis remains the method of choice to evaluate genes of interest conferring susceptibility to specific disease. Most genes contributing to MN susceptibility remain unidentified; well-organized approach like GWASs may obtain definite conclusions regarding such genes in the near future.

Acknowledgements

This study is supported in part by Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare Clinical Trial and Research Center of Excellence (DOH102-TD-B-111-004), China Medical University Hospital (DMR-102-086) in Taiwan.

References

- [1].Lewis EJ. Management of nephrotic syndrome in adults. In: Cameron JS, Glassock RJ, editors. The nephrotic syndrome. New York: Marcel Dekker. 1988; 461–521.

- [2].Schieppati A, Mosconi L, Perna A, Mecca G, Bertani T, Garattini S, Remuzzi G. Prognosis of untreated patients with idiopathic membranous nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:85–89. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307083290203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Philibert D, Cattran D. Remission of proteinuria in primary glomerulonephritis: we know the goal but do we know the price? Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2008;4:550–59. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Glassock RJ. Diagnosis and natural course of membranous nephropathy. Semin Nephrol. 2003;23:324–32. doi: 10.1016/S0270-9295(03)00049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ponticelli C. Membranous nephropathy. J Nephrol. 2007;20:268–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Chen KH, Chang CT, Hung CC. Glomerulonephritis associated with chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Ren Fail. 2006;28:255–59. doi: 10.1080/08860220600580415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Yen TH, Huang JY, Chen CY. Unexpected IgA nephropathy during the treatment of a young woman with idiopathic dermatomyositis: case report and review of the literature. J Nephrol. 2003;16:148–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Chen SY, Chen CC, Huang YC, Chan CJ, Hsieh YY, Tu MC. Association of STAT4 Polymorphisms with Susceptibility to Primary Membranous Glomerulonephritis and Renal Failure. Clin Chim Acta. 2011;412:899–904. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Chen YT, Wei CC, Ng KL, Chen CH, Chan CJ, Chen XX. Toll-like receptor 9 SNPs are susceptible to the development and progression of membranous glomerulonephritis: 27 years follow up in Taiwan. Renal Failure. 2013;35:1370–75. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2013.828264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Chen SY, Chen CH, Huang YC, Chuang HM, Lo MM, Tsai FJ. Effect of IL-6 C-572G Polymorphism on Idiopathic Membranous Nephropathy Risk in a Han Chinese Population. Renal Failure. 2010;32:1172–76. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2010.516857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Chen SY, Chen WC, Chen CH, Huang YC, Lin YW, Lin WY. Association of Toll-like Receptor 4 Gene Polymorphisms with Primary Membranous Nephropathy in High-Prevalence Area, Taiwan. ScienceAsia. 2010;36:130–36. doi: 10.2306/scienceasia1513-1874.2010.36.130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chen WC, Chen SY, Chen CH, Chen HY, Lin YW, Ho TJ. Lack of Association between Transient Receptor Potential Cation Channel 6 Polymorphisms and Primary Membranous Glomerulonephritis. Renal Failure. 2010;32:666–72. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2010.485289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lo WY, Chen SY, Wang HJ, Shih HC, Chen CH, Tsai CH, Tsai FJ. Association between genetic polymorphisms of the NPHS1 gene and membranous glomerulonephritis in the Taiwanese population. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411:714–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chen YT, Chen CH, Yen CH, Chen SY, Tsai FJ. Association between MYH9 gene polymorphisms and membranous glomerulonephritis patients in Taiwan. Science Asia. 2013;39:625–30. doi: 10.2306/scienceasia1513-1874.2013.39.625. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ihle JN. The Stat family in cytokine signaling. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:211–17. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(00)00199-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Watford WT, Hissong BD, Bream JH, Kanno Y, Muul L, O’Shea JJ. Signaling by IL-12 and IL-23 and the immunoregulatory roles of STAT4. Immunol Rev. 2004;202:139–56. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Skapenko A, Leipe J, Lipsky PE, S chulze-Koops H. The role of the T cell in autoimmune inflammation. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:S4–S14. doi: 10.1186/ar1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kobayashi S, Ikari K, Kaneko H, Kochi Y, Yamamoto K, Shimane K. Association of STAT4 with susceptibility to rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus in the Japanese population. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1940–46. doi: 10.1002/art.23494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Korman BD, Alba MI, Le JM, Alevizos I, Smith JA, Nikolov NP. Variant form of STAT4 is associated with primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Genes Immun. 2008;9:267–70. doi: 10.1038/gene.2008.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Remmers EF, Plenge RM, Lee AT, Graham RR, Hom G, Behrens TW. STAT4 and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:977–86. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rueda B, Broen J, Simeon C, Hesselstrand R, Diaz B, Suarez H. The STAT4 gene influences genetic predisposition to systemic sclerosis phenotype. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:2071–77. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zervou MI, Mamoulakis D, Panierakis C, Boumpas DT, Goulielmos GN. STAT4: a risk factor for type 1 diabetes? Hum Immunol 2008; 69: 647–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [23].Medzhitov R, Janeway CJ. The Toll receptor family and microbial recognition. Trends Microbiol. 2008;8:452–56. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(00)01845-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Shirali AC, Goldstein DR. Tracking the toll of kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1444–50. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008010123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Gluba A, Banach M, Hannam S, Mikhailidis DP, Sakowicz A, Rysz J. The role of Toll-like 15 receptors in renal diseases. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2010;6:224–35. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2010.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Pawar RD, Ramanjaneyulu A, Kulkarni OP, Lech M, Segerer S. Anders HJ.Inhibition of Toll-like receptor-7 (TLR-7) or TLR-7 plus TLR-9 attenuates glomerulonephritis and lung injury in experimental lupus. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1721–31. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006101162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Papadimitraki ED, Tzardi M, Bertsias G, Sotsiou E, Boumpas DT. Glomerular expression of toll-like receptor-9 in lupus nephritis but not in normal kidneys: implications for the amplification of the inflammatory response. Lupus. 2009;18:831–35. doi: 10.1177/0961203309103054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Summers SA, Steinmetz OM, Ooi JD, Gan PY, O’Sullivan KM, Visvanathan K. Toll-like receptor 9 enhances nephritogenic immunity and glomerular leukocyte recruitment, exacerbating experimental crescentic glomerulonephritis. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:2234–44. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Boswell JM, Yiu MA, Burt DW, Kelley VE. I. ncreased tumour necrosis factor and IL-1 beta gene expression in the kidneys of mice with lupus nephritis. J Immunol. 1988;141:3050–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Boswell JM, Yui MA, Endres S, Burt DW, Kel ey VE. Novel and enhanced IL-1 gene expression in autoimmune mice with lupus. J Immunol. 1988;141:118–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Noble B, Ren KI, Tavernes J, Dipirro J, Van Liew J, Dukstra C. Mononuclear cells in glomeruli and cytokines in urine reflect the severity of experimental proliferative immune complex glomerulonephritis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1990;80:281–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1990.tb05248.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Horii Y, Muraguchi A, Iwano M, Matsuda T, Hirayama T, Dukstra H. Involvement of IL-6 in mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis. J Immunol 1989. 1989;143:3449–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Dohi K, Iwano M, Muraguchi A, Horii Y, Hirayama T, Ogawa S. The prognostic significance of urinary interleukin 6 in IgA nephropathy. Clin Neplhrol 1991. 1989;86:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Gordon C, Richards N, Howie AJ, Richardson K, Michael J, Adu D. TUrinary IL-6: a marker for mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis? Clin Exp Immunol 1991. 1989;86:145–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1991.tb05787.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Lee CH, Wu CL, Shiau AL. Toll-like receptor 4 signaling promotes tumor growth. J Immunother. 2010;33:73–82. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181b7a0a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Medzhitov R, Janeway C. Jr. The Toll receptor family and microbial recognition. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:452–56. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(00)01845-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Lin FY, Chen YH, Chen YL, Wu TC, Li CY, Chen JW. Ginkgo biloba extract inhibits endotoxininduced human aortic smooth muscle cell proliferation via suppression of toll-like receptor 4 expression and NADPH oxidase activation. J Agr Food Chem. 2007;55:1977–84. doi: 10.1021/jf062945r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Zouiten-Mekki L, Kharrat M, Karoui S, Serghimi M, Fekih M, Matri S. Tolllike receptor 4 (TLR4) polymorphisms in Tunisian patients with Crohn’s disease: genotype-phenotype correlation. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-9-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Rigoli L, Romano C, Caruso RA, Lo Presti MA, Di Bella C, Procopio V, et al. Clinical significance of NOD2/CARD15 and Toll-like receptor 4 gene single nucleotide polymorphisms in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14: 454-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [40].Cristofaro P, Opal SM. Role of Toll-like receptors in infection and immunity: clinical implications. Drugs. 2006;66:15–29. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200666010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Huber TB, Kottgen M, Schilling B, Walz G, Benzing T. Interaction with podocin fecilitates nephrin signaling. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:41543–46. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100452200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Wartiovaara J, Ofverstedt LG, Khoshnoodi J, Zhang J, Makela E, Sandin S. Nephrin strands contribute to a porous slit diaphragm scaffold as revealed by electron tomography. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1475–83. doi: 10.1172/JCI22562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Patrakka J, Tryggvason K. Nephrin—a unique structural and signaling protein of the kidney filter. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Zenker M, Machuca E, Antignac C. Genetics of nephrotic syndrome: new insights into molecules acting at the glomerular filtration barrier. J Mol Med. 2009;87:849–57. doi: 10.1007/s00109-009-0505-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Niaudet P. Genetic forms of nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2004;19:1313–18. doi: 10.1007/s00467-004-1676-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Franceschini N, North KE, Kopp JB, Mckenzie L, Winkler C. NPHS2 gene, nephrotic syndrome and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: a HuGE review. Genet Med. 2006;8:63–75. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000200947.09626.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Arrondel C, Vodovar N, Knebelmann B, Gr¨unfeld JP, Gubler MC, Antignac C, Heidet L. Expression of the nonmuscle myosin heavy chain IIA in the human kidney and screening for MYH9 mutations in Epstein and Fechtner syndromes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:65–74. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V13165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Singh N, Nainani N, Arora P, Venuto RC. CKD in MYH9-related disorders. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54:732–40. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Pecci A, Biino G, Fierro T, Bozzi V, Mezzasoma A, Noris P. Alteration of liverenzymes is a feature of the MYH9-related disease syndrome. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e35986. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Kao WH, Klag MJ, Meoni LA, Reich D, Berthier-Schaad Y, Li M. Family investigation of nephropathy and diabetes research group. MYH9 is associated with nondiabetic end-stage renal disease in African Americans. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1185–92. doi: 10.1038/ng.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Kopp JB, Smith MW, Nelson GW, Johnson RC, Freedman BI, Bowden DW. MYH9 is a major-effect risk gene for focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1175–84. doi: 10.1038/ng.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Freedman BI, Hicks PJ, Bostrom MA, Comeau ME, Divers J, Bleyer AJ. Non-muscle myosin heavy chain 9 gene MYH9 associations in African Americans with clinically diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus-associated ESRD. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:3366–71. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Freedman BI, Kopp JB, Winkler CA, Nelson GW, Rao DC, Eckfeldt JH. Polymorphisms in the nonmuscle myosin heavy chain 9 gene (MYH9) are associated with albuminuria in hypertensive African Americans: the HyperGEN study. Am J Nephrol. 2009;29:626–32. doi: 10.1159/000194791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Pattaro C, Aulchenko YS, Isaacs A, Vitart V, Hayward C, Franklin CS. Genomewide linkage analysis of serum creatinine in three isolated European populations. Kidney Int. 2009;76:297–306. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Ramos RG, Igloi GL, Lichte B, Baumann U, Maier D, Schneider T. The irregular chiasm C-roughest locus of Drosophila, which affects axonal projections and programmed cell death, encodes a novel immunoglobulin-like protein. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2533–47. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12b.2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Schneider T, Reiter C, Eule E, Bader B, Lichte B, Nie Z. Restricted expression of the irreC-rst protein is required for normal axonal projections of columnar visual neurons. Neuron. 1995;15:259–71. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Kestilä M, Lenkkeri U, Männikkö M, Lamerdin J, McCready P, Putaala H. Positionally cloned gene for a novel glomerular protein—nephrin—is mutated in congenital nephrotic syndrome. Mol Cell. 1998;1:575–82. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80057-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Donoviel DB, Freed DD, Vogel H, Potter DG, Hawkins E, Barrish JP. Proteinuria and perinatal lethality in mice lacking NEPH1, a novel protein with homology to NEPHRIN. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:4829–36. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.14.4829-4836.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Ruotsalainen V, Ljungberg P, Wartiovaara J, Lenkkeri U, Kestilä M, Jalanko H. Nephrin is specifically located at the slit diaphragm of glomerular podocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7962–67. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Lin WY, Liu HP, Chang JS, Lin YJ, Wan L, Chen SY. Genetic variations within the PSORS1 region affect Kawasaki disease development and coronary artery aneurysm formation. BioMedicine. 2013;3:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.biomed.2013.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Liao WL, Tsai FJ. Personalized medicine: A paradigm shift in healthcare. BioMedicine. 2013;3:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.biomed.2012.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]