Abstract

Objectives

Considering equity into guidelines presents methodological challenges. This study aims to qualitatively synthesise the methods for incorporating equity in clinical practice guidelines (CPGs).

Setting

Content analysis of methodological publications.

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies

Methodological publications were included if they provided checklists/frameworks on when, how and to what extent equity should be incorporated in CPGs.

Data sources

We electronically searched MEDLINE, retrieved references, and browsed guideline development organisation websites from inception to January 2013. After study selection by two authors, general characteristics and checklists items/framework components from included studies were extracted. Based on the questions or items from checklists/frameworks (unit of analysis), content analysis was conducted to identify themes and questions/items were grouped into these themes.

Primary outcomes

The primary outcomes were methodological themes and processes on how to address equity issues in guideline development.

Results

8 studies with 10 publications were included from 3405 citations. In total, a list of 87 questions/items was generated from 17 checklists/frameworks. After content analysis, questions were grouped into eight themes (‘scoping questions’, ‘searching relevant evidence’, ‘appraising evidence and recommendations’, ‘formulating recommendations’, ‘monitoring implementation’, ‘providing a flow chart to include equity in CPGs’, and ‘others: reporting of guidelines and comments from stakeholders’ for CPG developers and ‘assessing the quality of CPGs’ for CPG users). Four included studies covered more than five of these themes. We also summarised the process of guideline development based on the themes mentioned above.

Conclusions

For disadvantaged population-specific CPGs, eight important methodological issues identified in this review should be considered when including equity in CPGs under the guidance of a scientific guideline development manual.

Keywords: QUALITATIVE RESEARCH, PUBLIC HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Methodological challenges are the barriers of incorporating equity into guidelines. For this topic, this study synthesises some themes (‘scoping questions’, ‘searching relevant evidence’, ‘appraising evidence and recommendations’, ‘formulating recommendations’, ‘monitoring implementation’, ‘providing a flow chart to include equity in CPGs’, and ‘others: reporting of guidelines and comments from stakeholders’ for clinical practice guidelines (CPG) developers and ‘assessing the quality of CPGs’ for CPG users) and a developing process through a content analysis of eight studies.

These findings allow the guideline panel to consider equity issues into guidelines and contribute methodologists to develop a methodological document in future.

These findings provide some valuable guidance, however no statement on methodological issues in equity or new checklist is built.

Background

Health is defined by the WHO as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’.1 Health outcomes can be influenced by inaccessibility to health interventions for certain population groups, such as the poor and because of unequal distribution of medical resources. When differences in health outcomes across socioeconomic, demographic and geographic factors are avoidable, unnecessary and unjust they are described as health inequities.2 3 The WHO recognises that inequities in health should be reduced since health is a fundamental human right4 and, in 2005, set up the Commision on Social Determinants of Health to collect, collate and synthesise evidence on inequities and to make recommendations for action to address them.5

Inequities in health and healthcare are well documented in relation to social and economic factors, according to the actronym PROGRESS-Plus, including Place of residence, Race/ethnicity/culture/language, Occupation, Gender/sex, Religion, Education, Socioeconomic status and Social capital6 and additional factors related to personal characteristic, features of relationships and time-dependent characteristics (captured by ‘Plus’).7 Equity issues have been shown to have negative effects on health status.8–13 For example, as Wallace et al14 reported, the HIV epidemics structure in the USA was influenced by two such determinants, the link between geographic regions and the socioeconomic structure, function and history of the regions.

Clinical practice guidelines (CPGs), as defined by the Institute of Medicine, are ‘systematically developed statements to assist practitioner and patient decisions about appropriate healthcare for specific clinical circumstances.’15 They are an increasingly familiar part of clinical practice and may provide concise guidance on which assessment programmes to order, how to provide medical or surgical interventions, or other details of clinical practice.16 Guideline development is becoming more evidence-based.17 CPGs advocate that the most effective therapies are recommended as suggested by the evidence, however, the most effective intervention may not be available to all groups within a population. For example, a new therapy may be effective, but CPG developers need to consider whether it is available (and sufficiently cost-effective) for disadvantaged populations.18

Therefore, CPG developers should discuss whether recommendations can ensure equitable provision of healthcare for the disadvantaged. Regardless of the setting, there is potential for the CPG to introduce inequities. Differences in health outcomes across population groups are possible if equity is not considered in guideline development. CPGs and their recommendations have the potential to create or increase health inequities.19 The inclusion of equity considerations in CPG development and implementation has become increasingly important.20 21 For example, to balance the effective versus efficiency dilemma of CPGs, the National Health Service (NHS) recommends the development of guiding principles to support the pursuit of equity in healthcare.22 However, incorporating equity into guidelines remains a challenge; the main barriers are methodological and conceptual limitations.20 23 We aimed to review methods for including equity considerations in CPGs in this paper.

Present investigation

Eligibility criteria

We conducted this review to investigate methodological guidance for including equity in CPGs. Only methodological guidance, guidelines and articles that described when, how and to what extent equity issues could be incorporated in CPGs were included in this review. Types of eligible studies included: guidelines for incorporating equity into CPGs, empirical literature discussing equity-specific methodological issues of CPG development, quantitative or qualitative literature reviews that identify equity-specific methodological elements of CPG development.

Information sources and search

Relevant studies were obtained from the following sources.

MEDLINE (1966 to January 2013) was electronically searched using an adapted version of the search strategy developed by Haase et al24 for the identification of clinical practice guidelines: (recommendation[All Fields] OR ‘consensus’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘consensus’[All Fields] OR ‘guideline’[Publication Type] OR ‘guidelines as topic’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘guideline’[All Fields]) AND (equal* OR equal[All Fields] OR ‘Civil Rights’[Mesh] OR equity[All Fields] OR equit*) limited in ‘Humans and Title/Abstract’;

Relevant studies were retrieved from reference lists of eligible articles;

In January 2013, we browsed guideline development organisations’ websites including: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), New Zealand Guidelines Group, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), Guideline International Network (G-I-N), CMA Infobase: Clinical Practice Guidelines, PUBGLE, Trip Database and National Guideline Clearinghouse, etc;

Online publications from the ‘International Journal for Equity in Health’ (from 2002 to January 2013) was manually searched;

We also emailed SIGN, the New Zealand Guidelines Group and National Guideline Clearinghouse, etc to access specific documents.

Study selection and data collection process

Authors CHS and QW independently screened titles and abstracts. The full text (if published) of all potentially relevant studies were retrieved and independently assessed for inclusion by QW and KHY. CHS and KHY carried out data extraction independently using a standard data extraction form (see online supplementary appendix 1). We planned to translate papers reported in non-English language journals (if any) before assessment. Where more than one publication on the same guidance existed, only the publication with the most complete data was included. Any further information or clarification required from the authors was requested by written or electronic correspondence and relevant data obtained in this manner were included in the review. Disagreements were resolved in consultation with coauthors.

Data items

In this review, data items are the questions or items from all available instruments, checklists, critical appraisal tools and indices which were designed to guide the incorporation of equity issues into CPGs or assessing the quality of equity considerations within CPGs. No data on participants, interventions, comparators, clinical outcomes and study designs was extracted.

Synthesis of results

Written phrases were the unit of analysis and therefore no quantitative data were analysed by specific software. Using content analysis, authors CHS and JHT synthesised methodological themes and processes on how to address equity issues in guideline development. Content analysis is ‘a research technique for making replicable and valid inferences from data to their context.’,25 which ‘emphasises the quantification of the ‘what’ that messages communicate, the ‘who’ (the source), the ‘why’ (the encoding process) and the consequences of ‘effects’ they have ‘on whom’,25 by which themes can be summarised from meaningful qualitative data. A simplified process was used in this review: identifying units of analysis (the items/questions), excluding irrelevant information, abstracting the phrase or words from each unit of analysis, labelling these concepts, grouping them, and creating themes to link the underlying concepts together in categories (see online supplementary appendix 2). No additional analysis was used in this review.

Results

Guidance selection

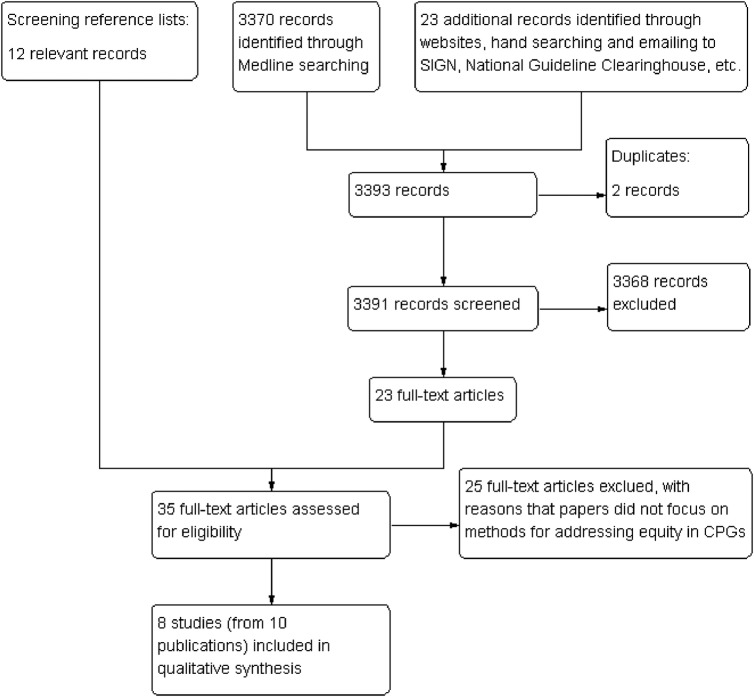

We retrieved 3370 citations from MEDLINE and 23 additional citations from the guideline development organisation websites, the International Journal for Equity in Health and emailing guideline development organisations. After removing duplicates and reviewing titles and abstracts, 3368 citations were excluded. By reviewing reference lists of the remaining 23 full-text articles, we obtained 12 relevant citations. In total, 35 potentially relevant full texts were screened, out of which 25 full-texts were excluded. The main reason for exclusion was that the focus of the papers was not on methods for addressing equity in CPGs. Finally, 8 studies with 10 publications19–21 26–32 were included in this review (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Selection process of included studies.

Study characteristics

Six studies19–21 26 27 31 were retrieved from MEDLINE, and four28–30 32 were identified from guideline development organisations’ websites. Only three studies19 21 26 defined equity issues according to different definitions.2 33 34 Included studies focused on different methodological topics related to equity including why,19 when,26 what26 and how19 20 26–32 CPG developers should address equity issues in CPGs, and how to assess the quality of CPGs, including equity,21 for CPG users. Five studies (from 7 publications)19 20 27–30 32 did not provide details of financial support. The characteristics of the included studies are provided in the table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Study | Journal/sources | Publication type | Definition of equity | Scope | Targeted users | Funding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eslava-Schmalbach et al19 | Rev. salúd publica | Review | Casas-Zamora,34 Whitehead2 | Why, How | CPGs developers* | No declaration |

| Dans et al21 | Journal of Clinical Epidemiology | Article | Braveman,33 Whitehead2 | Assessing the quality of CPGs | CPGs users | Rockefeller Foundation, Norwegian Health Services Research Center |

| Oxman et al26 | Health Research Policy and Systems | Review | Braveman,33 Whitehead2 | When, What, How | CPGs developers | WHO, Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services |

| Acosta et al27 | Rev. salúd publica | Review | None provided | How | CPGs developers | No declaration |

| NICE28 and NICE29 |

NICE | Guideline | None provided | How | CPGs developers | No declaration |

| Aldrich et al20 and NHMRC30 |

BMJ and NHMRC |

Article and guideline | None provided | How | CPGs developers | No declaration |

| Keuken et al31 | Dissertation | Dissertation | None provided | How | CPGs developers* | Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development |

| WHO32 | WHO | Guideline | None provided | How | CPGs developers | No declaration |

*Indicates that original studies did not report their targeted users by themselves and authors of this study specified them to be clinical practice guidelines developers.

CPGs, clinical practice guidelines.

In terms of relevant information extracted and analysed, Keuken et al31 provided ‘Recommendation for focusing on sex-related factors in guideline development’; NICE28 29 provided ‘The protected characteristics’, ‘Equality in guideline development’, a ‘Checklist for scoping’, a ‘Checklist for early guideline development’ and a ‘Checklist for formulating recommendations’; Dans et al21 provided ‘The equity lens’ to assess the quality of guidelines including equity issues; targeting at on the WHO guidelines mainly, Oxman et al26 reviewed related articles to provide guidance to address equity in guidelines; Eslava-Schmalbach J et al19 described why equity issues should be addressed in guidelines; Acosta et al27 provided simple guidance for including equity in guidelines; Aldrich et al20 and NHMRC30 provided indicators and search terms for socioeconomic factors and a framework for using evidence on socioeconomic factors in the development of clinical practice guidelines; rather than focusing on equity issues in particular, the WHO32 provided advice on equity issues in its ‘PICO question components’ and evidence retrieval and synthesis’ sections.

Synthesis of results

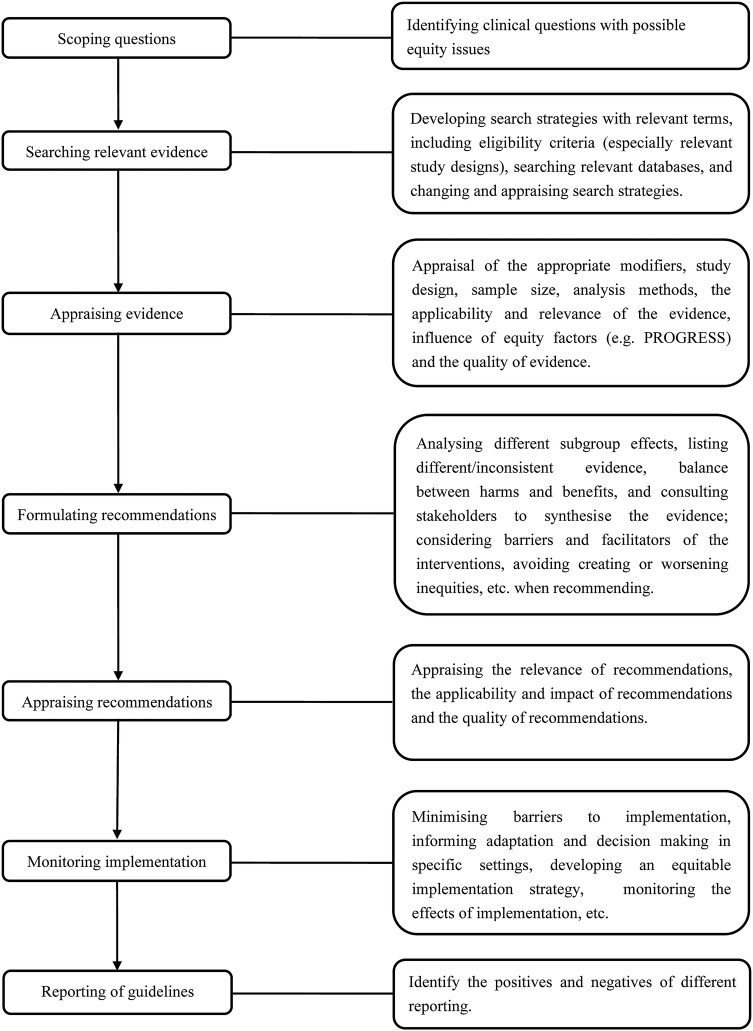

In total, 87 questions/items were collected. After content analysis, eight themes (seven for CPG developers, one for CPG users) were identified as following (see online supplementary appendix 3). Then based on them, we outlined an integrated CPG development process for developers, including seven steps in total (see figure 2).

Figure 2.

Overview of clinical practice guidelines development process (for CPGs developers).

For CPG developers:

Scoping questions

Seven studies19 20 26–32 reported the development of CPGs should include ‘Scoping questions’ by which CPG developers could consider the reasons for addressing equity in their CPG (ie, differential effectiveness across groups, negative impact of guideline without equity considerations, and improving overall effectiveness of guideline within equity),19 the scenario and timing when equity should be addressed (eg, the presence of differential effects across groups),26 targeted populations, social determinants of health specified by PROGRESS or PROGRESS-Plus frameworks,6 7 and the changes and comments from stakeholders for the proposed question.28 29

Searching relevant evidence

Four of the included studies20 28–32 (six publications) described the ‘Searching relevant evidence’ theme, including appropriate study designs, changing search strategies when necessary, using terms/markers for equity and appraising the eligibility criteria.

Appraising evidence and recommendations

Five studies20 26–31 with seven publications fulfilled the ‘Appraising evidence and recommendations’ theme, including the appraisal of scientific evidence, such as the appraisal of appropriate modifiers, study design, sample size, analysis methods, the applicability and relevance of evidence, influence of equity evidences, the quality of evidence, the necessity of evidence and making changes and evidence gaps, as well as the appraisal of recommendations, such as the relevance of recommendations, the impact of recommendations and the quality of development process.

Formulating recommendations

Three studies20 28–31 with five publications provided guidance for how CPG developers should formulate recommendations to address equity issues as well as the elements that should be considered when synthesising the evidence and formulating recommendations, including analysing different subgroup effects, listing different/inconsistent evidence, balancing harms and benefits for disadvantaged populations, formulating equitable recommendations (such as considering barriers and facilitators of interventions for disadvantaged populations and mitigating negative effects that may produce inequities during the formulation of recommendations), and how to advance recommendations and adjust recommendations.

Monitoring implementation

Four studies20 26 27 30 31 with five publications described the ‘Monitoring implementation’ theme. These studies included guidance on what should be considered during the implementation of CPGs and how to monitor implementation. Guidance suggested that CPG developers should minimise barriers to implementation, inform adaptation and decision-making in some specific settings, develop an equitable implementation strategy, change the organisational structure, and monitor the effects of implementation. When no evidence is available, CPG developers should change search strategies, scope of the questions and promotion strategies.

Providing a flow chart to include equity in CPGs

Four studies19 20 28–31 were included in the ‘Providing a flow chart to include equity in CPGs’ theme. These included following common steps: identifying questions, developing search strategies, appraising scientific evidence, synthesising the evidence, formulating recommendations and writing the guideline documents. Almost all of the elements in this theme were captured by the other themes except ‘Synthesising the evidence’. This additional element suggests that CPG developers should analyse subgroup effects, describe different/inconsistent evidence, balance harms and benefits and consult comments from stakeholders.

Others: reporting of guidelines and comments from stakeholders

Keuken et al31 reported the knowledge needs for the various ways of reporting guidelines. The authors stated that CPGs developers should balance advantages and disadvantages of different reporting methods. NICE28 29 highlighted the need for engagement with stakeholders during every stage of the development process.

For the CPGs users

Assessing the quality of CPGs

Dans et al21 reported how CPG users can assess the quality of CPGs. This study includes limited guidance, including whether recommendations considered priorities for disadvantaged populations, and factors to explore differential effects across groups during the scoping stage. The authors suggest CPG users assess whether differential effects of the intervention across groups are valued, consider these when implementing the recommendations in practice, and address barriers to implementation, and the impact of the recommendations.

Discussion

Summary of evidence

We identified eight studies with 10 publications focusing on how to address equity issues in guidelines. Using different definitions of health equity the eight guiding studies may result in the difference of identifying the same conditions related to equity. Few studies provided methodological guidance to help CPG users identify important information on equity. After qualitative analysis, eight themes were identified, which included ‘scoping questions’, ‘searching relevant evidence’, ‘appraising evidence’, ‘formulating recommendations’, ‘monitoring implementation’, ‘providing a flow chart to include equity in CPGs’, and ‘others: reporting of guidelines and comments from stakeholders’ for CPG developers and ‘assessing the quality of CPGs’ for CPG users. Most of the included studies provided CPG developers or users with open-ended questions in checklists/frameworks rather than with a tool (with examples) to judge why, what, when and how equity issues should be addressed. Few guidance publications described how to assess the quality of CPGs which considered equity issues in their recommendations, the process for developing CPGs, or how to report equity considerations. NHMRC,30 Keuken et al,31 Aldrich et al20 and NICE28 29 covered more than five themes.

All included studies reported the ‘scoping questions’ theme. When a guideline is developed, a rational for equity considerations should be described based on the differential effectiveness of interventions between subgroups. The PROGRESS and PROGRESS-Plus acronyms are recommended for identifying potentially disadvantaged groups when describing the scope of the CPG.6 Four studies20 28–32 described the ‘searching relevant evidence’ theme, but, only NICE28 29 suggested the consideration of study design. NHMRC30 and Aldrich et al20 provided search terms on equity issues. Identifying evidence including systematic reviews, clinical practice guidelines, randomised controlled trials and supplementary literature is essential for CPG development. The search strategy must be transparent and reproducible. The reporting of databases, time periods, key words, subject headings, language restrictions, grey literature and eligibility criteria should be considered.35

Before formulating recommendations, the quality of scientific evidence must be appraised by appropriate appraisal tools. The relevance, applicability, impact of evidence on equity and evidence gaps should be assessed. Equity-specific CPG developers should focus on important questions, for example whether CPGs gave priority to the disadvantaged, how the applicability of the CPG and its evidence for disadvantaged populations was assessed, and whether implementation and monitoring strategies will detect effects for the most disadvantaged.36 When evidence gaps exist, expert opinion or consensus is necessary to allow CPG developers to highlight future research needs.35 NHMRC30 and Aldrich et al20 provide strategies that can be used when there is a lack of evidence. For specific population subgroups, guideline developers should counterpoise harms and benefits of interventions, consider barriers and facilitators of interventions, and adjust recommendations for specific settings. Only Dans AM (2007) provided an equity lens to appraise the quality of a CPG with equity considerations. For the development of a CPG, we suggest that a well-designed handbook such as the ‘WHO handbook for guideline development’,32 ‘SIGN 50 A guideline developer's handbook’,37 ‘Handbook on Clinical Practice Guidelines’38 or NICE ‘the guidelines manual 2012’28 is utilised. The process of CPG development (figure 2) outlined in this paper will be more effective when used in combination with the handbooks mentioned above.

Limitations

With the comprehensive search strategy, only eight studies (containing 87 questions or items) were included in this review. However, compared to previous reviews,27 our study includes a wider collection of handbooks and guidance documents. Although Acosta et al27 included 20 studies (of which only three21 26 30 were included in our review), the authors only discussed equity in the development of CPGs with a narrative literature review. We extracted the methodological checklists/frameworks from the eligible studies and conducted content analysis. Content analysis was used because of its methodological characteristics and reliable measures to achieve trustworthiness.39 However, a limitation of content analysis is that the likelihood of replicability for the analysis procedure is low.25

Conclusions

By reviewing the existing guidance documents and guidelines, eight themes (ie, ‘scoping questions’, ‘searching relevant evidence’, ‘appraising evidence and recommendations’, ‘formulating recommendations’, ‘monitoring implementation’, ‘providing a flow chart to include equity in CPGs’, and ‘others: reporting of guidelines and comments from stakeholders for CPGs developers and ‘assessing the quality of CPGs’ for CPGs users) were identified for guiding the incorporation of equity issues into clinical practice guidelines. Among existing checklists, Keuken et al31 and NHMRC30 covered most of these themes and have the greatest potential to be used as a tool for guiding equity considerations in guidelines. No grading systems or scoring criteria were found from existing checklists.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: CS, JT and KY took part in conceiving and designing this review. CS, QW and KY were involved in searching, extracting data and analysing the data. CS, JT, DRN, JP and YY participated in writing, amending and revising the manuscript. When disagreements arose, they were solved through discussion with KY and JT. CS, JT, QW, DR, JP, KY and YY approved the final manuscript. JP and YY made important comments and were involved in English editing.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. The constitution of the World Health Organization. World Health Organization Chronicles, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitehead M. The concepts and principles of equity in health. Int J Health Serv 1992;22:429–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ministry of Health. Reducing inequalities in health. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Health Systems: Equity. http://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/equity/en (accessed 25 Sep 2013).

- 5.CSDH. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Neill J, Tabish H, Welch V et al. Applying an equity lens to interventions: using PROGRESS ensures consideration of socially stratifying factors to illuminate inequities in health. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:56–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oliver S, Dickson K, Newman M. Getting started with a review. In: Gough D, Oliver S, Thomas J, eds. An introduction to systematic reviews. London, UK: SAGE Publications, 2012:67–81.. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Long JA, Chang VW, Ibrahim SA et al. Update on the health disparities literature. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:805–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vogel TR. Update and review of racial disparities in sepsis. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2012;13:203–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang H, Dwyer-Lindgren L, Lofgren KT et al. Age-specific and sex-specific mortality in 187 countries, 1970–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2071–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallace R, Wallace D. Socioeconomic determinants of health: community marginalisation and the diffusion of disease and disorder in the United States. BMJ 1997;314:1341–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2197–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2095–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wallace R, Huang Y, Gould P et al. The hierarchical diffusion of AIDS and violent crime among US metropolitan regions: innercity decay, stochastic resonance and reversal of the mortality transition. Soc Sci Med 1997;44:935–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.IOM (Institute of Medicine). Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington DC: The National Academies Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woolf SH, Grol R, Hutchinson A et al. Potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. BMJ 1999;318:527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shekelle PG, Woolf SH, Eccles M et al. Clinical guidelines: developing guidelines. BMJ 1999;318:593–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McFarlane P. Not all guidelines are created equal. CMAJ 2006;174:814; discussion 815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eslava-Schmalbach J, Sandoval-Vargas G, Mosquera P. Incorporating equity into developing and implementing for evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Rev Salud Pública (Bogota) 2011;13:339–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aldrich R, Kemp L, Williams JS et al. Using socioeconomic evidence in clinical practice guidelines. BMJ 2003; 327:1283–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dans AM, Dans L, Oxman AD et al. Assessing equity in clinical practice guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol 2007;60:540–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sassi F, Le Grand J, Archard L. Equity versus efficiency: a dilemma for the NHS. If the NHS is serious about equity it must offer guidance when principles conflict. BMJ 2001;323:762–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burgers JS, Grol R, Klazinga NS et al. Towards evidence-based clinical practice: an international survey of 18 clinical guideline programs. Int J Quality Healthcare 2003;15:31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haase A, Follmann M, Skipka G et al. Developing search strategies for clinical practice guidelines in SUMSearch and Google Scholar and assessing their retrieval performance. BMC Med Res Methodol 2007;7:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krippendorff K. Content analysis. An introduction to its methodology. London: The Sage Commtext Series, Sage Publications Ltd., 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oxman AD, Schünemann HJ, Fretheim A. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 12. Incorporating considerations of equity. Health Res Policy Syst 2006; 4:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Acosta N, Pollard J, Mosquera P et al. [The concept of equity when developing clinical practice guidelines]. [Article in Spanish]. Rev Salud Publica (Bogota) 2011;13:327–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. The guidelines manual 2012. http://publications.nice.org.uk/the-guidelines-manual-pmg6 (accessed 29 Oct 2013).

- 29.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Positively equal: a guide to addressing equality issues in developing NICE clinical guidelines. 2nd edn London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2012. http://www.nice.org.uk [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Health and Medical Research Council. Using socioeconomic evidence in clinical practice guidelines. Canberra: NHMRC, 2003:95 http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/publications/synopses/cp65syn.htm (accessed 20 Jan 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keuken DG, Haafkens JA, Moerman CJ et al. Attention to sex-related factors in the development of clinical practice guidelines. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2007;16:82–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization. WHO handbook for guideline development. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press, 2012. http://www.who.int [Google Scholar]

- 33.Braveman PA, Gruskin S. Defining equity in health. J Epidemiol Community Health 2003;57:254e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Casas-Zamora JA, Ibrahim SA. Confronting health inequity: the global dimension. Am J Public Health 2004;94:2055–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenfeld RM, Shiffman RN, Robertson P. Clinical Practice Guideline Development Manual, Third Edition: a quality-driven approach for translating evidence into action. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2013;148(1 Suppl):S1–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dans AL, Dans LF. Appraising a tool for guideline appraisal (the AGREE II instrument). J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:1281–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. SIGN 50 a guideline developer's handbook. http://www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/50/index.html (accessed 29 Oct 2013).

- 38.Canadian Medical Association. Guidelines for Canadian clinical practice guidelines. http://mdm.ca/cpgsnew/cpgs/gccpg-e.htm (accessed 29 Oct 2013).

- 39.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today 2004;24:105–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.