Abstract

Purpose

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and American Urological Association (AUA) provide guidelines for surveillance after surgery for renal cell carcinoma (RCC). Herein, we assess the ability of the guidelines to capture RCC recurrences and determine the duration of surveillance required to capture 90%, 95%, and 100% of recurrences.

Patients and Methods

We evaluated 3,651 patients who underwent surgery for M0 RCC between 1970 and 2008. Patients were stratified as AUA low risk (pT1Nx-0) after partial (LR-partial) or radical nephrectomy (LR-radical) or as moderate/high risk (M/HR; pT2-4Nx-0/pTanyN1). Guidelines were assessed by calculating the percentage of recurrences detected when following the 2013 and 2014 NCCN and AUA recommendations, and associated Medicare costs were compared.

Results

At a median follow-up of 9.0 years (interquartile range, 5.7 to 14.4 years), a total of 1,088 patients (29.8%) experienced a recurrence. Of these, 390 recurrences (35.9%) were detected using 2013 NCCN recommendations, 742 recurrences (68.2%) were detected using 2014 NCCN recommendations, and 728 recurrences (66.9%) were detected using AUA recommendations. All protocols missed the greatest amount of recurrences in the abdomen and among pT1Nx-0 patients. To capture 95% of recurrences, surveillance was required for 15 years for LR-partial, 21 years for LR-radical, and 14 years for M/HR patients. Medicare surveillance costs for one LR-partial patient were $1,228.79 using 2013 NCCN, $2,131.52 using 2014 NCCN, and $1,738.31 using AUA guidelines. However, if 95% of LR-partial recurrences were captured, costs would total $9,856.82.

Conclusion

If strictly followed, the 2014 NCCN and AUA guidelines will miss approximately one third of RCC recurrences. Improved surveillance algorithms, which balance patient benefits and health care costs, are needed.

INTRODUCTION

Multiple protocols exist for the oncologic surveillance of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) after surgical resection. However, there is no consensus as to which protocol is most effective.1,2 Single institutions and national organizations, such as the National Comprehensive Cancer Institute (NCCN) and American Urological Association (AUA), have formulated recommendations that are either generalized3–5 or based on tumor stage6–9 or integrated prognostic algorithms.10–14 Without prospective or randomized trials, there is no definitive evidence to clarify which protocol is the most efficacious. As a result, significant heterogeneity in the delivery of surveillance care has developed, leading to both the over- and underutilization of testing for certain patient groups.15

The NCCN and AUA represent two highly recognized RCC surveillance guidelines in the medical community. However, until recently, these protocols were greatly disparate. In 2014, the NCCN updated their recommendations from those that advocated the same protocol for all patients to a strategy that uses a risk-adapted algorithm similar to the AUA.5 Despite this recent change, the NCCN and AUA protocols are not uniform. This lack of protocol conformity among guidelines perpetuates the heterogeneity within surveillance practice. Variability in care delivery can translate into inefficient medical resource allocation and loss of health care dollars. As reimbursement becomes tightly connected to standardized guidelines, it is important to understand which surveillance strategies are most effective. Herein, we sought to evaluate the performance of the 2013 NCCN, recently updated 2014 NCCN, and AUA guidelines, by determining how many RCC recurrences after surgery would be detected when abiding by the prescribed protocols. We then summarized the total duration of surveillance required to capture 90%, 95%, and 100% of RCC recurrences when using a surveillance design that incorporated location-specific recurrence patterns among risk groups. Finally, a 2014 Medicare cost comparison was performed among established guidelines and for the hypothetical situation if surveillance was extended to capture 95% of RCC recurrences.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Sample

After obtaining institutional review board approval, we reviewed our prospectively maintained renal tumor registry and identified 3,803 patients treated with radical or partial nephrectomy for M0 sporadic RCC between 1970 and 2008. A total of 152 patients were excluded because of missing tumor stage classification (n = 55), fewer than 30 days of follow-up (n = 42), development of metastatic disease within 30 days of surgery (n = 24), receipt of neoadjuvant therapy (n = 19), a rare histologic subtype of RCC (n = 7), or intraoperative death (n = 5). Given the retrospective nature of the study, surveillance regimens were not standardized. However, the majority of patients received a history/physical examination, laboratory testing, and abdominal and chest imaging quarterly for the first 2 years, semiannually for the next 3 years, and then annually thereafter. Bone scan and brain imaging were performed only when clinically indicated.

Classification of Disease Recurrence

Disease recurrence was defined as demonstrable metastasis on imaging studies or via biopsies at least 30 days after surgery. Recurrences were classified according to location as abdomen, chest, bone, or other sites, which included the CNS and skin. Use of these particular locations allowed for direct translation into the types of imaging or clinical procedures that could be used for surveillance. Recurrence in the location of the abdomen included both locoregional relapse and visceral sites. The first recurrence in time for each patient was counted as an event, and all other recurrences were censored to prevent double counting. Recurrences occurring simultaneously in multiple locations were individually counted as events.

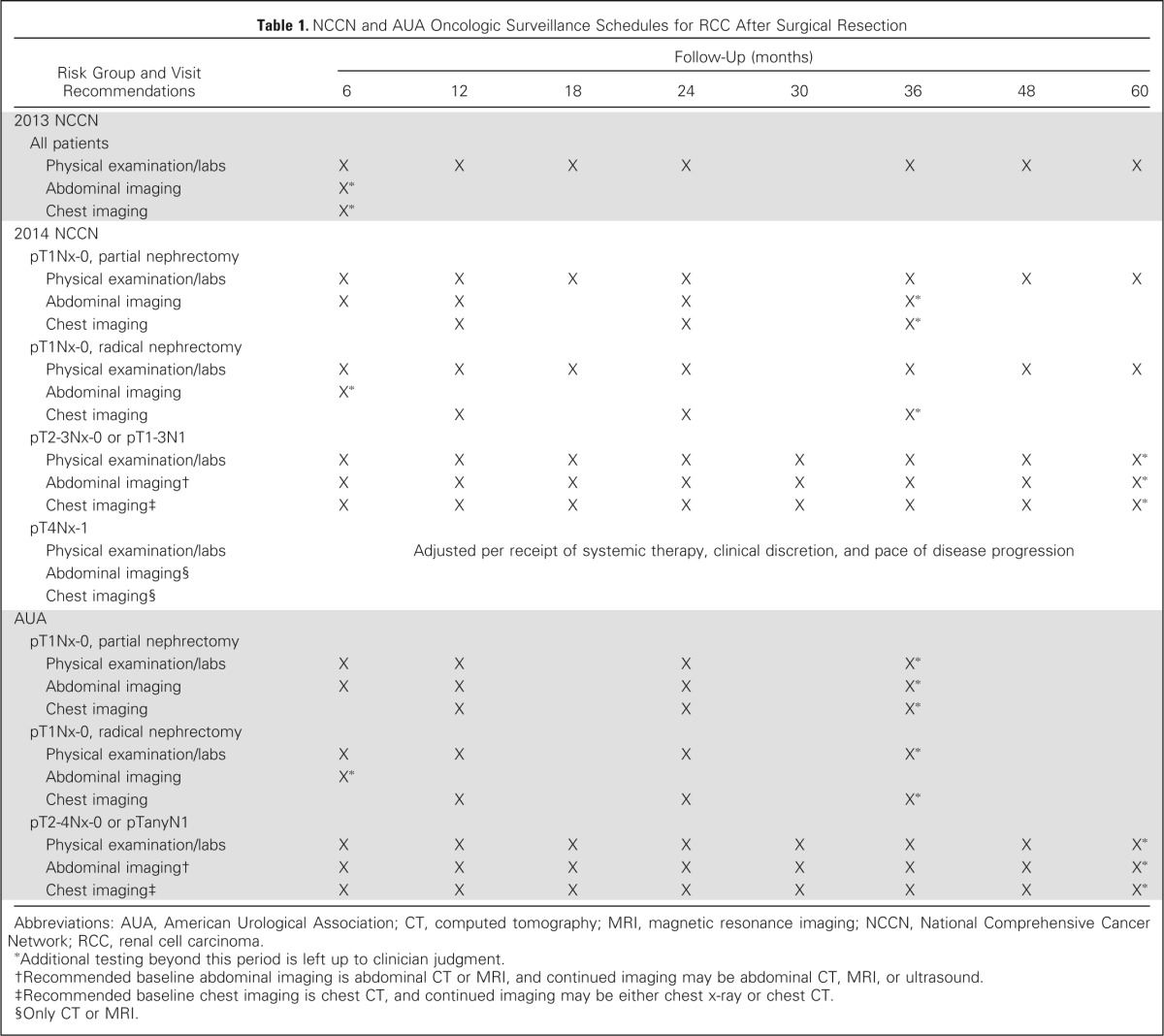

Evaluation of Current Guidelines

Table 1 lists the current surveillance protocols according to the 2013 NCCN, 2014 NCCN, and AUA recommendations. We evaluated the ability of these guidelines to capture recurrences by determining the total number of recurrences that would be detected if patients were strictly observed for the length of time recommended for each location—abdomen, chest, bone, and other sites. Because recurrences in bone and other sites are detected clinically or via imaging used for the chest or abdomen, the length of time to detect recurrences in these locations was based on the time recommended for the physical examination/labs. Thus, according to the 2013 NCCN guidelines, recurrences would have been detected in the abdomen and chest if captured within 6 months and in bone and other sites if captured within 5 years16 (Table 1).

Table 1.

NCCN and AUA Oncologic Surveillance Schedules for RCC After Surgical Resection

| Risk Group and Visit Recommendations | Follow-Up (months) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 12 | 18 | 24 | 30 | 36 | 48 | 60 | |

| 2013 NCCN | ||||||||

| All patients | ||||||||

| Physical examination/labs | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Abdominal imaging | X* | |||||||

| Chest imaging | X* | |||||||

| 2014 NCCN | ||||||||

| pT1Nx-0, partial nephrectomy | ||||||||

| Physical examination/labs | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Abdominal imaging | X | X | X | X* | ||||

| Chest imaging | X | X | X* | |||||

| pT1Nx-0, radical nephrectomy | ||||||||

| Physical examination/labs | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Abdominal imaging | X* | |||||||

| Chest imaging | X | X | X* | |||||

| pT2-3Nx-0 or pT1-3N1 | ||||||||

| Physical examination/labs | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X* |

| Abdominal imaging† | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X* |

| Chest imaging‡ | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X* |

| pT4Nx-1 | ||||||||

| Physical examination/labs | Adjusted per receipt of systemic therapy, clinical discretion, and pace of disease progression | |||||||

| Abdominal imaging§ | ||||||||

| Chest imaging§ | ||||||||

| AUA | ||||||||

| pT1Nx-0, partial nephrectomy | ||||||||

| Physical examination/labs | X | X | X | X* | ||||

| Abdominal imaging | X | X | X | X* | ||||

| Chest imaging | X | X | X* | |||||

| pT1Nx-0, radical nephrectomy | ||||||||

| Physical examination/labs | X | X | X | X* | ||||

| Abdominal imaging | X* | |||||||

| Chest imaging | X | X | X* | |||||

| pT2-4Nx-0 or pTanyN1 | ||||||||

| Physical examination/labs | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X* |

| Abdominal imaging† | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X* |

| Chest imaging‡ | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X* |

Abbreviations: AUA, American Urological Association; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; RCC, renal cell carcinoma.

Additional testing beyond this period is left up to clinician judgment.

Recommended baseline abdominal imaging is abdominal CT or MRI, and continued imaging may be abdominal CT, MRI, or ultrasound.

Recommended baseline chest imaging is chest CT, and continued imaging may be either chest x-ray or chest CT.

Only CT or MRI.

To evaluate both the 2014 NCCN and AUA guidelines, patients were first stratified according to stage and surgical approach. Both guidelines used a similar stratification for low-risk patients, as follows: low risk (pT1Nx-0) after partial nephrectomy (LR-partial) and low risk after radical nephrectomy (LR-radical). The AUA stratified the remainder of patients into a moderate-/high-risk group (M/HR; pT2-4Nx-0/pTanyN1) independent of surgical approach, whereas the 2014 NCCN guidelines separated out high-risk patients into the following two groups: pT2-3Nx-0/pT1-3N1 and pT4Nx-1 (Table 1). Thus, according to the 2014 NCCN guidelines,5 LR-partial recurrences to the abdomen and chest would have been detected up to 3 years after surgery and up to 5 years for recurrences to the bone and other sites. Whereas, LR-radical patients had up to 1 year for recurrences to be detected in the abdomen, up to 3 years for the chest, and up to 5 years for bone and other sites. For patients with pT2-3Nx-0/pT1-3N1 disease, a total of 5 years was allowed for the detection of recurrences to all sites. Because the 2014 NCCN follow-up for pT4Nx-1 patients is dependent on their receipt of systemic therapy, pace of disease progression, and clinical discretion, we estimated that such recommendations would facilitate the capture of all recurrences. In regard to the AUA guidelines,14 LR-partial patients had up to 3 years after surgery to detect recurrences to all sites and M/HR patients had up to 5 years. For LR-radical patients, recurrences in the abdomen would have been detected up to 1 year after surgery and up to 3 years for the chest, bone, and other sites (Table 1).

Medicare Cost Analysis

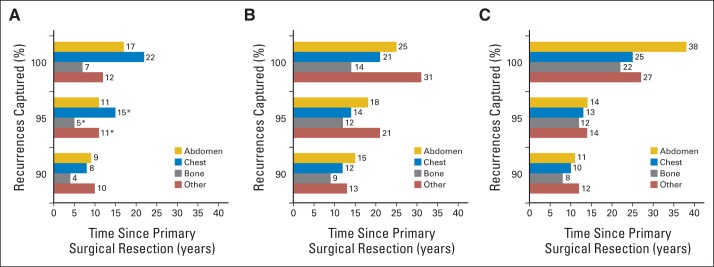

Using the 2014 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services fee schedule, the nonfacility global costs associated with the 2013 and 2014 NCCN and AUA guidelines were estimated on a per-patient basis when strictly adhering to and completing the recommended follow-up schedules as shown in Table 1. The Common Procedural Terminology codes used in the analysis included 99214 (established midlevel office visit), 74170 (computed tomography of abdomen), 71250 (computed tomography of chest), 71020 (chest x-ray), 80053 (complete metabolic panel), and 85027 (CBC). Use of alternative imaging, such as magnetic resonance imaging or ultrasound, or additional imaging beyond that which was specified according to the protocols was not applied to the cost analysis. Finally, the cost of capturing 95% of all recurrences was estimated using the total duration of follow-up outlined in Figure 1 and frequency of testing used during surveillance at the Mayo Clinic.

Fig 1.

Total duration of surveillance required to capture 90%, 95%, and 100% of recurrences in patients stratified by American Urological Association risk groups and recurrence locations: (A) low risk after partial nephrectomy; (B) low risk after radical nephrectomy; and (C) moderate/high risk. (*) Estimated duration of surveillance as a result of the few recurrences in these groups.

Statistical Analysis

The duration of surveillance required to capture 90%, 95%, and 100% of recurrences was summarized by AUA risk group and location using the cumulative frequency of time to recurrence. Because of the few recurrences in the chest (n = 9), bone (n = 6), and other sites (n = 5) for LR-partial patients, there was no corresponding time point associated with the capture of 95% of recurrences. Therefore, the duration of surveillance required to capture 95% of recurrences in LR-partial patients at these locations was estimated to be halfway between the time points to capture 90% and 100% of recurrences. Recurrence rates after surgery were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences were evaluated using log-rank tests. Clinicopathologic features between LR-partial and LR-radical patients were compared using Wilcoxon rank sum, χ2, Cochran-Armitage trend, and Fisher's exact tests. All tests were two-sided, with P < .05 considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

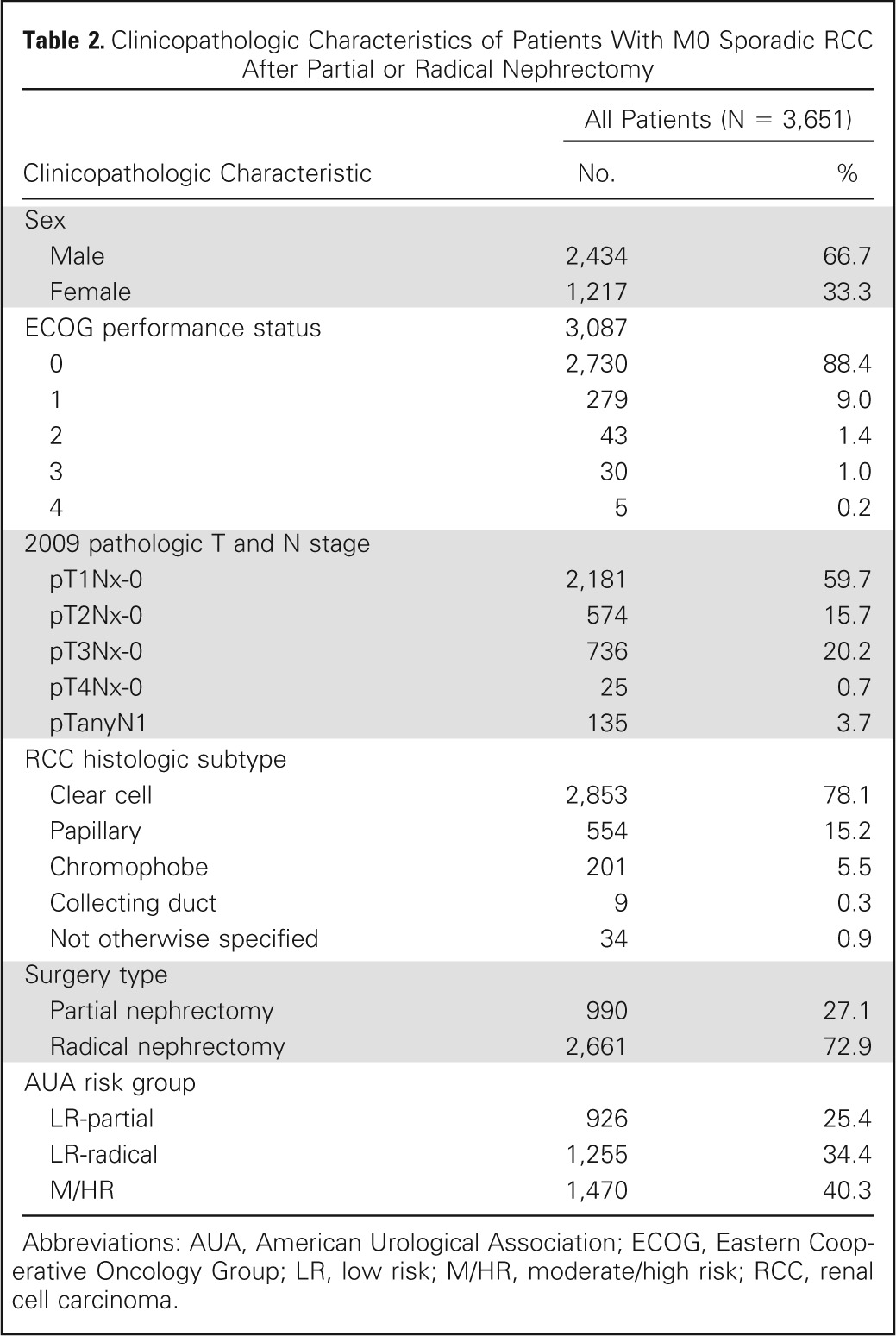

Of the 3,651 patients who underwent partial or radical nephrectomy, 1,088 patients (29.8%) developed disease recurrence at a median of 1.9 years (interquartile range [IQR], 0.6 to 5.5 years) after surgery (range, 0.1 year to 37.5 years). Median postoperative follow-up was 9.0 years (IQR, 5.7 to 14.4 years). Table 2 lists patient clinicopathologic features. The median age for the group was 64 years (IQR, 54 to 71 years).

Table 2.

Clinicopathologic Characteristics of Patients With M0 Sporadic RCC After Partial or Radical Nephrectomy

| Clinicopathologic Characteristic | All Patients (N = 3,651) |

|

|---|---|---|

| No. | % | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 2,434 | 66.7 |

| Female | 1,217 | 33.3 |

| ECOG performance status | 3,087 | |

| 0 | 2,730 | 88.4 |

| 1 | 279 | 9.0 |

| 2 | 43 | 1.4 |

| 3 | 30 | 1.0 |

| 4 | 5 | 0.2 |

| 2009 pathologic T and N stage | ||

| pT1Nx-0 | 2,181 | 59.7 |

| pT2Nx-0 | 574 | 15.7 |

| pT3Nx-0 | 736 | 20.2 |

| pT4Nx-0 | 25 | 0.7 |

| pTanyN1 | 135 | 3.7 |

| RCC histologic subtype | ||

| Clear cell | 2,853 | 78.1 |

| Papillary | 554 | 15.2 |

| Chromophobe | 201 | 5.5 |

| Collecting duct | 9 | 0.3 |

| Not otherwise specified | 34 | 0.9 |

| Surgery type | ||

| Partial nephrectomy | 990 | 27.1 |

| Radical nephrectomy | 2,661 | 72.9 |

| AUA risk group | ||

| LR-partial | 926 | 25.4 |

| LR-radical | 1,255 | 34.4 |

| M/HR | 1,470 | 40.3 |

Abbreviations: AUA, American Urological Association; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; LR, low risk; M/HR, moderate/high risk; RCC, renal cell carcinoma.

In the 1,088 patients who experienced recurrence, there were 437 abdominal recurrences (40.2%), 442 chest recurrences (40.6%), 166 bone recurrences (15.3%), and 158 recurrences to other sites (14.5%). Note that simultaneous recurrences in two or more locations were found among 102 patients (9.4%). For the 94 LR-partial patients, the majority of recurrences were within the abdomen compared with other locations (81.9% abdomen, 9.6% chest, 6.4% bone, and 5.3% other sites). For both the 190 LR-radical patients and the 804 M/HR patients, the majority of recurrences were in either the abdomen or chest (LR-radical: 44.2% abdomen, 34.7% chest, 15.3% bone, and 16.8% other; M/HR: 34.3% abdomen, 45.7% chest, 16.3% bone, and 15.1% other).

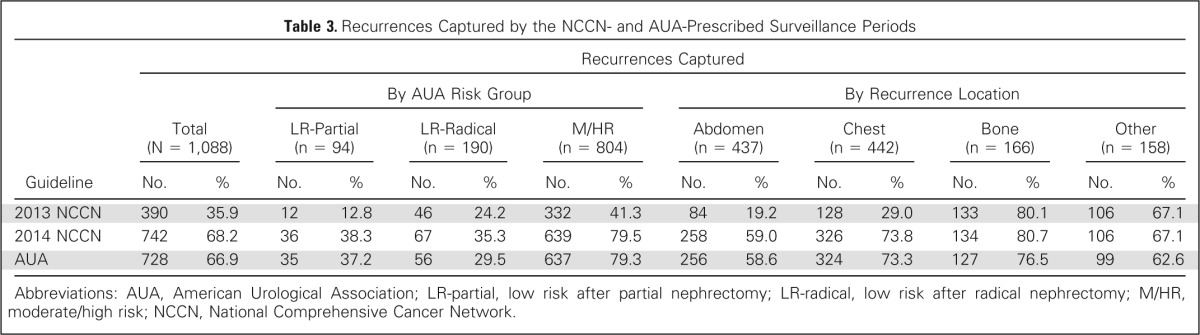

When evaluating the ability of the NCCN and AUA guidelines to capture recurrences after surgery, we found that the 2013 NCCN surveillance protocol would only capture 35.9% of all recurrences, whereas the updated 2014 NCCN risk-adapted protocol improved the overall detection rate to 68.2% (Table 3). With use of a similar risk-based approach, the AUA guidelines allowed detection of 66.9% of all recurrences. When evaluating the 2013 NCCN recommendations according to risk group and recurrence location, we found these guidelines to be most restrictive for LR-partial patients, where only 12.8% of recurrences were detected (Table 3). Both the 2014 NCCN and the AUA guidelines showed to be most limited for LR-radical patients, in which only 35.3% and 29.5% of recurrences were detected, respectively. Among the four recurrence locations, all of the guidelines were least likely to capture abdominal relapses, with only 19.2% detected by the 2013 NCCN guidelines, 59% detected by the 2014 NCCN guidelines, and 58.6% detected by the AUA guidelines. Overall, a greater percentage of recurrences were captured with the 2014 NCCN and AUA risk-adapted approaches.

Table 3.

Recurrences Captured by the NCCN- and AUA-Prescribed Surveillance Periods

| Guideline | Recurrences Captured |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 1,088) |

By AUA Risk Group |

By Recurrence Location |

||||||||||||||

| LR-Partial (n = 94) |

LR-Radical (n = 190) |

M/HR (n = 804) |

Abdomen (n = 437) |

Chest (n = 442) |

Bone (n = 166) |

Other (n = 158) |

||||||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2013 NCCN | 390 | 35.9 | 12 | 12.8 | 46 | 24.2 | 332 | 41.3 | 84 | 19.2 | 128 | 29.0 | 133 | 80.1 | 106 | 67.1 |

| 2014 NCCN | 742 | 68.2 | 36 | 38.3 | 67 | 35.3 | 639 | 79.5 | 258 | 59.0 | 326 | 73.8 | 134 | 80.7 | 106 | 67.1 |

| AUA | 728 | 66.9 | 35 | 37.2 | 56 | 29.5 | 637 | 79.3 | 256 | 58.6 | 324 | 73.3 | 127 | 76.5 | 99 | 62.6 |

Abbreviations: AUA, American Urological Association; LR-partial, low risk after partial nephrectomy; LR-radical, low risk after radical nephrectomy; M/HR, moderate/high risk; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

Incorporating location-specific recurrence patterns with the AUA risk groupings, a total duration of surveillance of 5 years or greater was required to capture 95% of recurrences. For example, to capture 95% of recurrences among LR-partial patients, surveillance of the abdomen would be required for 11 years, the chest for 15 years, bone for 5 years, and other sites for 11 years (Fig 1); whereas for LR-radical patients, surveillance of the abdomen would be required for 18 years, the chest for 14 years, bone for 12 years, and other sites for 21 years. In general, both LR-radical and M/HR patients required longer surveillance durations compared with LR-partial patients for similar recurrence locations. However, to capture 100% of recurrences, M/HR patients required the most extensive follow-up for the majority of locations.

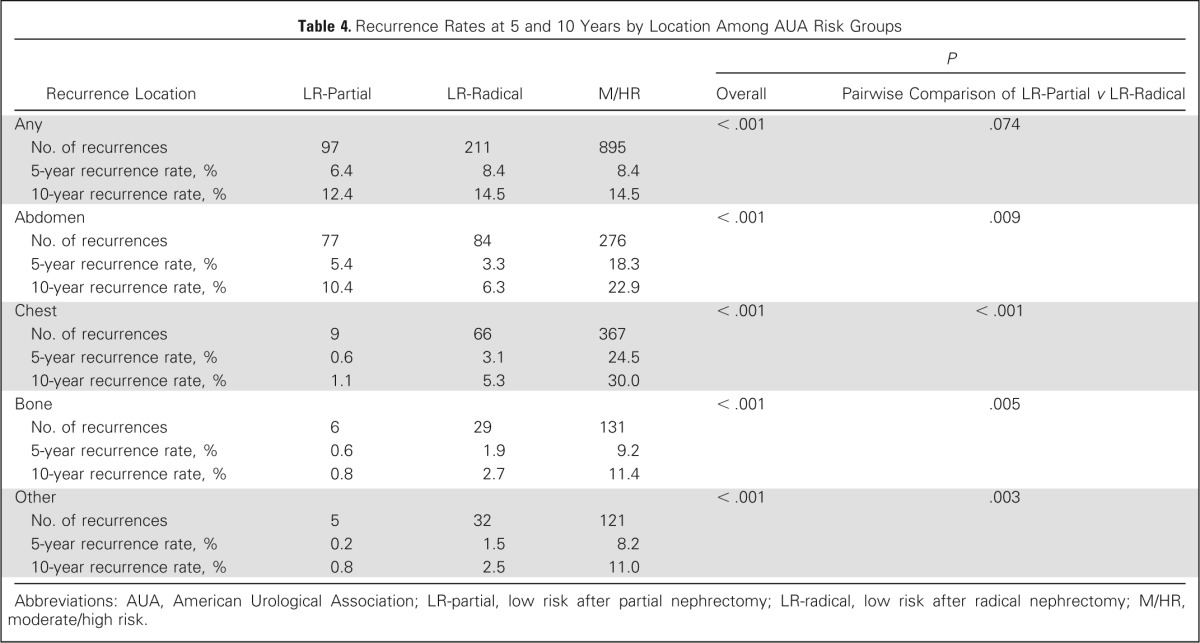

To explore the reasons for the differences in surveillance durations seen among the three risk groups, we analyzed their 5- and 10-year recurrence rates at each location (Table 4). Except for the abdomen, there was a consistent trend in which the LR-partial group had the lowest rate of recurrence and the M/HR group had the highest. Interestingly, LR-radical patients had significantly higher recurrence rates compared with LR-partial patients at all locations except for the abdomen. Because of this finding, we assessed differences in clinicopathologic features among the low-risk groups and found that LR-partial patients had less aggressive tumor characteristics. For example, LR-partial patients, compared with LR-radical patients, had more frequently papillary histology (25% v 14.9%, respectively; P < .001), a stage of pT1a (75.3% v 46.5%, respectively; P < .001), a smaller median tumor size (3 cm; IQR, 2.0 to 4.0 v 4.5 cm; IQR, 3.2 to 5.7, respectively; P < .001) and less sarcomatoid differentiation (1% v 12%, respectively; P = .011).

Table 4.

Recurrence Rates at 5 and 10 Years by Location Among AUA Risk Groups

| Recurrence Location | LR-Partial | LR-Radical | M/HR |

P |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Pairwise Comparison of LR-Partial v LR-Radical | ||||

| Any | < .001 | .074 | |||

| No. of recurrences | 97 | 211 | 895 | ||

| 5-year recurrence rate, % | 6.4 | 8.4 | 8.4 | ||

| 10-year recurrence rate, % | 12.4 | 14.5 | 14.5 | ||

| Abdomen | < .001 | .009 | |||

| No. of recurrences | 77 | 84 | 276 | ||

| 5-year recurrence rate, % | 5.4 | 3.3 | 18.3 | ||

| 10-year recurrence rate, % | 10.4 | 6.3 | 22.9 | ||

| Chest | < .001 | < .001 | |||

| No. of recurrences | 9 | 66 | 367 | ||

| 5-year recurrence rate, % | 0.6 | 3.1 | 24.5 | ||

| 10-year recurrence rate, % | 1.1 | 5.3 | 30.0 | ||

| Bone | < .001 | .005 | |||

| No. of recurrences | 6 | 29 | 131 | ||

| 5-year recurrence rate, % | 0.6 | 1.9 | 9.2 | ||

| 10-year recurrence rate, % | 0.8 | 2.7 | 11.4 | ||

| Other | < .001 | .003 | |||

| No. of recurrences | 5 | 32 | 121 | ||

| 5-year recurrence rate, % | 0.2 | 1.5 | 8.2 | ||

| 10-year recurrence rate, % | 0.8 | 2.5 | 11.0 | ||

Abbreviations: AUA, American Urological Association; LR-partial, low risk after partial nephrectomy; LR-radical, low risk after radical nephrectomy; M/HR, moderate/high risk.

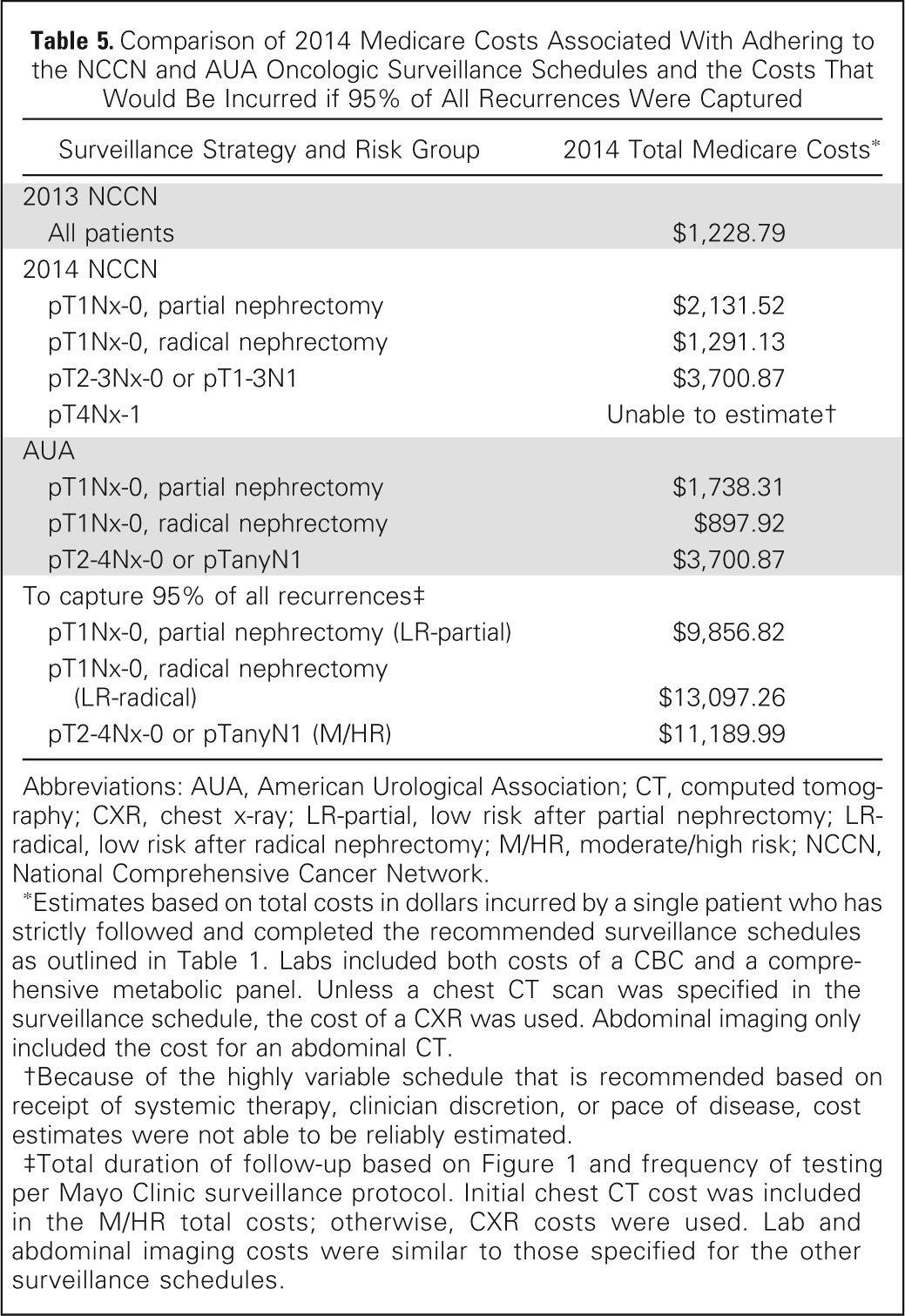

When assessing the total Medicare costs among guidelines, we found that a patient would incur the lowest cost, $1,228.79, if following the 2013 NCCN protocol (Table 5). Among the 2014 NCCN and AUA guidelines, the highest surveillance costs, $3,700.87, would be incurred by patients with high-risk disease because of the longer recommended follow-up. Similarly, on account of longer follow-up, an LR-partial patient would incur a greater cost for surveillance than an LR-radical patient (Table 5). However, to capture 95% of all recurrences, all risk groups would incur greater costs than those appreciated using current guidelines. For example, per-patient surveillance costs would be $9,856.82 for the LR-partial group, $13,097.26 for the LR-radical group, and $11,189.99 for the M/HR group.

Table 5.

Comparison of 2014 Medicare Costs Associated With Adhering to the NCCN and AUA Oncologic Surveillance Schedules and the Costs That Would Be Incurred if 95% of All Recurrences Were Captured

| Surveillance Strategy and Risk Group | 2014 Total Medicare Costs* |

|---|---|

| 2013 NCCN | |

| All patients | $1,228.79 |

| 2014 NCCN | |

| pT1Nx-0, partial nephrectomy | $2,131.52 |

| pT1Nx-0, radical nephrectomy | $1,291.13 |

| pT2-3Nx-0 or pT1-3N1 | $3,700.87 |

| pT4Nx-1 | Unable to estimate† |

| AUA | |

| pT1Nx-0, partial nephrectomy | $1,738.31 |

| pT1Nx-0, radical nephrectomy | $897.92 |

| pT2-4Nx-0 or pTanyN1 | $3,700.87 |

| To capture 95% of all recurrences‡ | |

| pT1Nx-0, partial nephrectomy (LR-partial) | $9,856.82 |

| pT1Nx-0, radical nephrectomy (LR-radical) | $13,097.26 |

| pT2-4Nx-0 or pTanyN1 (M/HR) | $11,189.99 |

Abbreviations: AUA, American Urological Association; CT, computed tomography; CXR, chest x-ray; LR-partial, low risk after partial nephrectomy; LR-radical, low risk after radical nephrectomy; M/HR, moderate/high risk; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

Estimates based on total costs in dollars incurred by a single patient who has strictly followed and completed the recommended surveillance schedules as outlined in Table 1. Labs included both costs of a CBC and a comprehensive metabolic panel. Unless a chest CT scan was specified in the surveillance schedule, the cost of a CXR was used. Abdominal imaging only included the cost for an abdominal CT.

Because of the highly variable schedule that is recommended based on receipt of systemic therapy, clinician discretion, or pace of disease, cost estimates were not able to be reliably estimated.

Total duration of follow-up based on Figure 1 and frequency of testing per Mayo Clinic surveillance protocol. Initial chest CT cost was included in the M/HR total costs; otherwise, CXR costs were used. Lab and abdominal imaging costs were similar to those specified for the other surveillance schedules.

DISCUSSION

In the first, to our knowledge, large-scale study to evaluate the NCCN and AUA surveillance guidelines for RCC, our results demonstrate that strict adherence to these protocols results in a number of missed recurrences after partial or radical nephrectomy. In fact, we found that 31.8% and 33.1% of all primary recurrences would have been missed by the 2014 NCCN and AUA guidelines, respectively, and that 64.1% of primary recurrences would have been missed if following the 2013 NCCN guidelines. The lowest number of recurrences captured among all three guidelines occurred in patients who were pT1Nx-0 or those who developed an abdominal relapse. Overall, the risk-adapted approaches advocated by the 2014 NCCN and AUA guidelines allowed for a greater percentage of recurrences to be identified. Incorporating recurrence location into the risk stratification used by the AUA allowed us to understand which risk groups and relapse sites required longer follow-up than what has previously been recommended.

Because relapse site influences recurrence patterns, adding this feature to the stratification schemes used in RCC surveillance may improve the number of recurrences detected. For example, in developing surveillance guidelines, Levy et al8 examined site-specific recurrence patterns among stage groups and found noticeable differences in time to recurrence. Indeed, the median time to recurrence for lung metastases was 53 months (range, 30 to 67 months) in pT1 patients, 31 months (range, 4 to 67 months) in pT2 patients, and 14 months (range, 5 to 59 months) in pT3 patients. Similar differences were observed among other recurrence sites such as bone, liver, and brain.8 When we included location into the stratification design, noticeable contrast in surveillance duration became evident among the three AUA risk groups. To capture the same percentage of recurrences, LR-radical patients necessitated a longer period of follow-up compared with LR-partial patients. These findings are in contrast to both the 2014 NCCN and AUA protocols, in which LR-radical patients are recommended the least intensive follow-up. When evaluating the differences in 5- and 10-year recurrence rates between these low-risk groups, we found that for all locations except the abdomen LR-radical patients had a higher recurrence rate than LR-partial patients. In our data set, investigation of differences between the two low-risk groups revealed that LR-radical patients were more likely to harbor adverse characteristics, such as increased tumor size, pT1b stage, and clear cell histology, which have all been associated with disease progression.17,18 These results support that LR-radical patients seem to be at a higher risk of recurrence compared with LR-partial patients and may warrant more rigorous follow-up than what has been recommended by guidelines.

In addition to showing more precisely the length of follow-up required for certain patient groups and locations, our evaluation, in general, highlighted the degree of undersurveillance that may be occurring when strictly abiding by current guidelines. Even for high-risk patients, all three guidelines provide no specific recommendations beyond 5 years. Although the risk-adapted strategies of the 2014 NCCN and AUA protocols were more successful at capturing recurrences than the 2013 NCCN guidelines, these updated algorithms still showed considerable shortcomings. By limiting specific abdominal and chest recommendations to 3 years or less for low-risk disease, the 2014 NCCN and AUA guidelines missed at least 60% of recurrences.

Although, extending surveillance beyond current recommendations may allow for a more comprehensive detection of recurrences, our cost analysis demonstrates that increased expenditures would be required. Compared with the costs associated with the 2014 NCCN and AUA guidelines, surveillance costs associated with the length of follow-up required to capture 95% of recurrences were three to 14 times more expensive; however, we submit that the Medicare costs for surveillance (approximately $10,000) to capture 95% of recurrences may not be unreasonable. This analysis highlights the importance of developing a more sophisticated approach to surveillance such that patient benefit can be balanced with health care costs. Development of such individualized surveillance protocols will become vital with the transition of health care into a more value-based system. For example, if the care of chronic conditions, such as the oncologic surveillance of patients with RCC, transitions away from specialist care, it will be of utmost importance to define effective care pathways that can be followed by the general practitioner. Furthermore, in such a system where reimbursement will be tightly connected with the adherence to standardized guidelines, it will be crucial to define the most effective protocol to prevent the unnecessary loss of health care dollars.

We recognize that our study is limited by its retrospective design. Although our follow-up was not standardized, the protocol instituted was uniform, and less than 3% of patients were lost to follow-up. Furthermore, any patient missing follow-up in this study would translate into an underestimate of the true number of missed recurrences. In addition, various imaging techniques were used during surveillance because our cohort spanned more than three decades. Although more advanced radiology techniques would have allowed earlier capture of recurrences, it is unlikely that using a contemporary cohort would eliminate the large differences found in follow-up length. Finally, because there is no strong evidence that surveillance for RCC or the detection of asymptomatic recurrences translates into a survival benefit, we acknowledge that the utility of improving such protocols remains in debate. However, despite this unknown, surveillance continues to remain an integral part of RCC care. This is likely a result of of patient preference, lack of opposing evidence, and the appreciation that treatment outcomes are improved with early detection of recurrences compared with detection at an advanced, symptomatic stage.8 Until research can determine the benefit of surveillance, we advocate for the investigation of more sophisticated and individualized surveillance approaches.

The NCCN and AUA surveillance guidelines do not comprehensively capture RCC recurrences after partial and radical nephrectomy. Our results suggest that even with the current 2014 NCCN and AUA recommendations, approximately one third of all recurrences are missed if these guidelines are strictly followed. However, extending surveillance to capture 95% of all recurrences, using similar algorithms, leads to higher costs. Thus, further research remains necessary to identify an optimal surveillance approach that balances patient benefit and health care costs.

Footnotes

See accompanying editorial on page 4031

Supported by Clinical and Translational Science Award Grant No. UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, a component of the National Institutes of Health.

Presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2014 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium, San Francisco, CA, January 31-February 1, 2014, and the 2014 Annual Meeting of the American Urological Association, Orlando, FL, May 16-21, 2014.

The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Suzanne B. Stewart, R. Houston Thompson, Stephen A. Boorjian, Bradley C. Leibovich

Administrative support: R. Houston Thompson, Stephen A. Boorjian, Bradley C. Leibovich

Provision of study materials or patients: R. Houston Thompson, John C. Cheville, Stephen A. Boorjian, Bradley C. Leibovich

Collection and assembly of data: Suzanne B. Stewart, R. Houston Thompson, John C. Cheville, Christine M. Lohse

Data analysis and interpretation: Suzanne B. Stewart, Sarah P. Psutka, Christine M. Lohse, Stephen A. Boorjian, Bradley C. Leibovich

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Skolarikos A, Alivizatos G, Laguna P, et al. A review on follow-up strategies for renal cell carcinoma after nephrectomy. Eur Urol. 2007;51:1490–1500. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chin AI, Lam JS, Figlin RA, et al. Surveillance strategies for renal cell carcinoma patients following nephrectomy. Rev Urol. 2006;8:1–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montie JE. Follow-up after partial or total nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma. Urol Clin North Am. 1994;21:589–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sandock DS, Seftel AD, Resnick MI. A new protocol for the followup of renal cell carcinoma based on pathological stage. J Urol. 1995;154:28–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Kidney Cancer 2.2014. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/kidney.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Gofrit ON, Shapiro A, Kovalski N, et al. Renal cell carcinoma: Evaluation of the 1997 TNM system and recommendations for follow-up after surgery. Eur Urol. 2001;39:669–674. doi: 10.1159/000052525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hafez KS, Novick AC, Campbell SC. Patterns of tumor recurrence and guidelines for followup after nephron sparing surgery for sporadic renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 1997;157:2067–2070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levy DA, Slaton JW, Swanson DA, et al. Stage specific guidelines for surveillance after radical nephrectomy for local renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 1998;159:1163–1167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stephenson AJ, Chetner MP, Rourke K, et al. Guidelines for the surveillance of localized renal cell carcinoma based on the patterns of relapse after nephrectomy. J Urol. 2004;172:58–62. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000132126.85812.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lam JS, Shvarts O, Leppert JT, et al. Postoperative surveillance protocol for patients with localized and locally advanced renal cell carcinoma based on a validated prognostic nomogram and risk group stratification system. J Urol. 2005;174:466–472. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000165572.38887.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ljungberg B, Alamdari FI, Rasmuson T, et al. Follow-up guidelines for nonmetastatic renal cell carcinoma based on the occurrence of metastases after radical nephrectomy. BJU Int. 1999;84:405–411. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.00202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siddiqui SA, Frank I, Cheville JC, et al. Postoperative surveillance for renal cell carcinoma: A multifactorial histological subtype specific protocol. BJU Int. 2009;104:778–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zisman A, Pantuck AJ, Wieder J, et al. Risk group assessment and clinical outcome algorithm to predict the natural history of patients with surgically resected renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4559–4566. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.05.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Urological Association. Follow-up for clinically localized renal neoplasms: AUA guideline 2013. http://www.auanet.org/education/guidelines/renal-cancer-follow-up.cfm. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Feuerstein MA, Huang WC, Russo P, et al. Patterns of surveillance imaging after nephrectomy in the Medicare population. Presented at the 14th Annual Meeting of the Society of Urologic Oncology; December 4-6, 2013; Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Motzer RJ, Agarwal N, Beard C, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Kidney cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7:618–630. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim SP, Weight CJ, Leibovich BC, et al. Outcomes and clinicopathologic variables associated with late recurrence after nephrectomy for localized renal cell carcinoma. Urology. 2011;78:1101–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leibovich BC, Blute ML, Cheville JC, et al. Prediction of progression after radical nephrectomy for patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma: A stratification tool for prospective clinical trials. Cancer. 2003;97:1663–1671. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]