Abstract

Objective

To synthesise qualitative studies that explore prescribers’ perceived barriers and enablers to minimising potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) chronically prescribed in adults.

Design

A qualitative systematic review was undertaken by searching PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, PsycINFO, CINAHL and INFORMIT from inception to March 2014, combined with an extensive manual search of reference lists and related citations. A quality checklist was used to assess the transparency of the reporting of included studies and the potential for bias. Thematic synthesis identified common subthemes and descriptive themes across studies from which an analytical construct was developed. Study characteristics were examined to explain differences in findings.

Setting

All healthcare settings.

Participants

Medical and non-medical prescribers of medicines to adults.

Outcomes

Prescribers’ perspectives on factors which shape their behaviour towards continuing or discontinuing PIMs in adults.

Results

21 studies were included; most explored primary care physicians’ perspectives on managing older, community-based adults. Barriers and enablers to minimising PIMs emerged within four analytical themes: problem awareness; inertia secondary to lower perceived value proposition for ceasing versus continuing PIMs; self-efficacy in regard to personal ability to alter prescribing; and feasibility of altering prescribing in routine care environments given external constraints. The first three themes are intrinsic to the prescriber (eg, beliefs, attitudes, knowledge, skills, behaviour) and the fourth is extrinsic (eg, patient, work setting, health system and cultural factors). The PIMs examined and practice setting influenced the themes reported.

Conclusions

A multitude of highly interdependent factors shape prescribers’ behaviour towards continuing or discontinuing PIMs. A full understanding of prescriber barriers and enablers to changing prescribing behaviour is critical to the development of targeted interventions aimed at deprescribing PIMs and reducing the risk of iatrogenic harm.

Keywords: QUALITATIVE RESEARCH, GERIATRIC MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the most comprehensive review to date of prescribers’ barriers and enablers to minimising potentially inappropriate medications which are chronically prescribed in adults.

Although database and manual searching was protracted and extensive, it is possible that not all relevant studies were found due to the poor indexing and inconsistent terminology for this topic.

Utilisation of a peer-reviewed, published method for thematic synthesis and a checklist to assess potential bias in studies contributed to the review’s methodological rigour.

The included studies largely explored primary care physicians’ perspectives on managing older, community-based adults in relation to relatively few drug classes and may limit the generalisability of the findings.

Introduction

Studies in the USA and Australia indicate that at least one in two older people (aged 65 years or greater) living in the community use five or more prescription, over-the-counter or complementary medicines every day, and the number used increases with age.1 2 Polypharmacy (the use of multiple medications concurrently) predisposes older people to being prescribed potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs), that is, where the actual or potential harms of therapy outweigh the benefits.3–5 Recent international data suggest that one in five prescriptions for community-dwelling older adults is inappropriate.6 In Australia, approximately 20–50% of individuals in this age group are prescribed one or more PIMs, with higher rates seen in residential aged care facilities (RACFs).3 7–10 For adults younger than 65 years of age, rates of prescribing of PIMs have not been quantified beyond single medication classes (eg, benzodiazepines, proton pump inhibitors). The rates and harms of polypharmacy in this population remain uncertain, although they are likely to be considerably less than that seen in older adults. In contrast, the harms of polypharmacy and prescribing of PIMs in older people are well established. Prescribing of PIMs is independently associated with adverse drug events, hospital presentations, poorer health-related quality of life and death.11 12 Up to 15% of all hospitalisations involving older people in Australia are medication-related, with one in five potentially preventable.13

These well-documented harms of prescribing PIMs should evoke a response from clinicians to identify and stop, or reduce the dose of, inappropriate medications as a matter of priority. While there is some evidence that PIM exposure has decreased marginally over recent years, its prevalence remains high.3 14–16 The process of reducing or discontinuing medications, with the goal of minimising inappropriate use and preventing adverse patient outcomes, is increasingly referred to as ‘deprescribing’.17 Although the term may be new, appropriate cessation or reduction of medication is a long accepted component of competent prescribing.18 19

The act of stopping a medication prescribed over months to years, however, is complicated by many factors related to patients and prescribers. These need to be understood if effective deprescribing strategies are to be developed. A recent review by Reeve et al20 identified patient barriers to, and enablers of, deprescribing, but to the best of our knowledge, no comprehensive review of prescribers’ perspectives has been reported, which this paper aims to provide.

Methods

In the absence of a universally accepted method to conduct a systematic review of qualitative data, we utilised principles of quantitative systematic review, applied to qualitative research,21 and were guided by the Cochrane endorsed ENTREQ (Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research) position statement.22

Search strategy and sources

An initial search was conducted to ensure that no systematic review on the same topic already existed. Two experienced health librarians were independently consulted in developing a comprehensive search strategy, which was informed by extensive prior scoping.23

PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus (limited to Health Sciences), PsycINFO, CINAHL and INFORMIT (Health Collection) electronic databases were searched from inception to March 2014. Filters to identify qualitative research were used and adapted to improve search sensitivity.24 These were combined with terms and text words for: medical and non-medical prescribers and either inappropriate prescribing or reducing, stopping or optimising medications. Terms/text words were searched in all/any fields or restricted to the title, abstract or keyword, depending on the size of the database and sophistication of its indexing. Reference lists and related citations of relevant articles were reviewed for additional studies. The full search strategy is detailed in the online supplementary appendix.

Study selection

After duplicate citations were excluded, one reviewer (KA) screened titles, abstracts and, where necessary, full text, to create a list of potentially relevant full text articles. Articles were required to meet provisional, intentionally overly inclusive, eligibility criteria to minimise the risk of inappropriate exclusions by the single reviewer. This list was forwarded to three reviewers (CF, DS and IS) who independently assessed the articles for inclusion. Discrepant views were resolved by group discussion to create the final list of included papers based on the refined eligibility criteria.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria comprised: (1) original research articles with a qualitative component (ie, qualitative, mixed or multimethod studies all accepted); and (2) focus on eliciting prescribers’ perspectives of factors that influence their decision to continue or cease chronically prescribed PIMs (as defined by the authors of each study) in adults.

No limits were placed on the care or practice setting of the patient or prescriber, respectively, or whether the article related to single or multiple medications.

Exclusion criteria comprised: (1) reviews, papers not published in English, and those for which the abstract or full text were not available; (2) focus on medication management decisions in the final weeks of life; (3) focus entirely on initiation of PIMs and (4) reported only quantitative data derived from structured questionnaires.

Assessment of the quality of studies

One researcher (KA) assessed the reporting of studies using the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist. This reporting guideline, endorsed by the Cochrane Collaboration, assesses the completeness of reporting and potential for bias in studies of interviews or focus groups.25 Any instances of interpretive uncertainty arising from the checklist were discussed and resolved within the four investigators.

Studies were not excluded or findings weighted on the basis of the COREQ assessment. Rather, we elected to include all studies, ascribing to the theory that the value of insights contained within individual studies may only become apparent at the point of synthesis rather than during the appraisal process.26

Data extraction process

For all included articles, data were extracted about study aims, location, setting, study design, participants, recruitment, PIMs examined and prescribers’ perspectives of factors influencing the chronic prescription of PIMs. Data for thematic analysis were only extracted from the results (not discussion) section of papers, with particular notice taken of quotations from prescriber participants.

Synthesis of results

The method used to synthesise results was based on the technique of thematic synthesis described by Thomas and Harden.27 Following multiple readings of the papers to achieve immersion, KA manually coded and extracted the text, and developed subthemes until no further subthemes could be identified. Two reviewers (DS and IS) independently read all papers and then reviewed the extracted, coded text and subthemes to confirm the comprehensiveness and reliability of the findings.28 Descriptive and draft analytical themes were subsequently developed by KA and then presented to, and discussed with, all investigators in developing and finalising the new analytical construct. The study characteristics and results were analysed for associations between specific themes and studies.

Results

Study selection

The search yielded 6011 papers, 21 of which met the selection criteria (see figure 1). There were no studies exploring the perspectives of non-medical prescribers.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of included studies are presented in table 1. All but one, which collected data by survey, used focus groups and semistructured interviews to collect qualitative data.29 Four papers explored prescribers’ views in relation to multiple medications (ie, polypharmacy)30–33 while the remaining papers investigated prescribers’ views in relation to single PIMs or classes of medications (10 described one or more centrally acting agents such as psychotropics, hypnotics, benzodiazepines, minor opiates and antidepressants34–43; 2 for proton pump inhibitors44 45 and 5 for miscellaneous PIMs defined according to prespecified criteria, a preset medication list or clinical judgement.29 46–49 Eighteen studies elicited the views of prescribers practising in primary care,29–41 44–48 one of the prescribers in secondary care,49 and two of the prescribers servicing RACFs.42 43

Table 1.

Studies investigating the perspectives of prescribers in various settings

| Year of publication | Lead author | Country | Aim | Medication types | Participants and setting | Age focus* | Data collection method | Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | Britten | England | To identify patients whose current medication is the result of past treatment decisions and is regarded by their current GP as no longer appropriate, and to describe the drugs and the circumstances in which they continue to be prescribed | Miscellaneous PIMs | 7 GPs, primary care | All ages | Descriptive survey; GP selected patients prescribed inappropriate medicines, structured data extraction from notes and GP-facilitated interview of patient | N/A |

| 1997 | Dybwad | Norway | To understand factors that could result in variations between GPs in order to form hypotheses and build theories about prescribing (main focus on factors that explain higher rates of prescribing) | Benzodiazepines and minor opiates | 38 GPs (18 high rate prescribers, 20 medium to low rate prescribers), primary care | All ages | SSIs (combined with prescription registration information) | Not stated |

| 1999 | Damestoy | Canada | To explore physicians’ perceptions and attitudes and the decision-making process associated with prescribing psychotropic medications for elderly patients | Psychotropics (sedatives, hypnotics, anxiolytics and antidepressants) | 9 physicians who conduct home visits, primary care | Older patients | (Presumed face-to-face) SSIs | Grounded theory analysis |

| 2000 | Cantrill | England and Scotland | To explore factors which may contribute to inappropriate long-term prescribing in UK general practice | Miscellaneous PIMs | 22 GPs, primary care | All ages | Face-to-face and telephone interviews informed by specific examples of PIMs identified by validated indicators | Not stated |

| 2004 | Iliffe | England | To explore beliefs and attitudes about continuing or stopping benzodiazepine hypnotics among older patients using such medicines, and among their GPs | Benzodiazepines | 72 GPs, primary care | Older patients | Non-standardised interview group discussions | Not stated |

| 2005 | Spinewine | Belgium | To explore the processes leading to inappropriate use of medicines for elderly patients admitted for acute care | Miscellaneous PIMs | 3 geriatricians and 2 house officers, hospital elderly acute care wards | Older patients | SSIs with health professionals triangulated with observation on wards and FGs with elderly inpatients | Not stated |

| 2005 | Raghunath | England | To understand the prescribing behaviour of GPs by exploring their knowledge, understanding and attitudes towards PPIs | PPIs | 49 GPs, primary care | All ages | Focus groups | Not stated |

| 2006 | Parr | Australia | To gain a more detailed understanding of GP and benzodiazepine user perceptions relating to starting, continuing and stopping benzodiazepine use | Benzodiazepines | 28 GPs, primary care | All ages | SSIs | Not stated |

| 2007 | Cook | USA | To understand factors influencing the chronic use of benzodiazepines in older adults | Benzodiazepines | 33 primary care physicians | Older patients | Face-to-face and telephone SSIs | Narrative analysis |

| 2007 | Rogers | England | To explore the dilemma the controversial benzodiazepine legacy has created for recent practitioners and their view of prescribing benzodiazepines | Benzodiazepines | 22 GPs, primary care | All ages | SSIs | Not stated |

| 2010 | Anthierens | Belgium | To describe GPs’ views and beliefs on polypharmacy in order to identify the role of the GP in improving prescribing behaviour | Polypharmacy | 65 GPs, primary care | Older patients | Face-to-face individual SSIs (literature informed interview guide) | Content analysis |

| 2010 | Dickinson | UK | To explore the attitudes of older patients and their GPs to chronic prescribing of antidepressant therapy, and factors influencing such prescribing | Antidepressants | 10 GPs, primary care | Older patients | SSIs | Framework analysis |

| 2010 | Frich | Norway | To explore GPs’ and tutors’ experiences with peer group academic detailing, and to explore GPs’ reasons for deviating from recommended prescribing practice | Miscellaneous PIMs | 20 GPs (39 GPs also interviewed on topics outside the scope of this review) | Older patients | Focus group interviews following individual receipt of prescription profile report | Thematic content analysis |

| 2010 | Moen | Sweden | To explore GPs’ perspectives of treating older users of multiple medicines | Polypharmacy | 31 GPs (4 private, 27 county-employed), primary care | Older patients | Focus groups (literature informed question guide) | Conventional content analysis |

| 2010 | Subelj | Slovenia | To investigate how high-prescribing family physicians explain their own prescription | Benzodiazepines | 10 family physicians (5 high and 5 low prescribers), primary care | All ages | SSIs | Not stated |

| 2011 | Fried | USA | To explore clinicians’ perspectives of and experiences with therapeutic decision-making for older persons with multiple medical conditions | Polypharmacy | 36 physicians, primary care, vet affairs and academia | Older patients | Focus groups | Content analysis |

| 2011 | Iden | Norway | To explore decision-making among doctors and nurses on antidepressant treatment in nursing homes | Antidepressants | 16 doctors, 8 each working full-time and part-time in residential aged care facilities | Older patients | Focus groups | Systematic text condensation and analysis |

| 2012 | Flick | Germany | To explore, given the specific risks and the limited effect of sleeping medication, why doctors prescribe hypnotics for the elderly in long-term care settings | Hypnotics | 20 prescribers servicing residential aged care facilities | Older patients | Episodic interviews | Thematic analysis |

| 2012 | Schuling | The Netherlands | To explore how experienced GPs feel about deprescribing medication in older patients with multimorbidity and to what extent they involve patients in these decisions | Polypharmacy | 29 GPs, primary care | Older patients | Focus groups | Not stated |

| 2013 | Clyne | Ireland | To evaluate GP perspectives on a pilot intervention (to reduce PIP in Irish primary care) | Miscellaneous PIMs | 8 GPs in the focus group and 5 GPs for SSIs, primary care | Older patients | Focus group and SSIs | Thematic analysis |

| 2013 | Wermeling | Germany | To describe factors and motives associated with the inappropriate continuation of prescriptions of PPIs in primary care | PPIs | 10 GPs (5 who frequently continue and 5 who frequently discontinue PPIs), primary care | All ages | SSIs | Framework analysis |

*Age focus refers to the indicative age group of patients who were the focus of participant discussions, as suggested by the terms used in each article, which did not specify the exact age ranges.

GPs, general practitioners; PIMs, potentially inappropriate medications; PIP, potentially inappropriate prescribing; PPIs, proton pump inhibitors; SSIs, semi-structured interviews.

COREQ assessment

The completeness of reporting varied across studies, with an average of 17 (range 8–22) of 32 items from the COREQ checklist clearly documented (table 2). The single descriptive survey reported 9 of 24 applicable fields.29 See online supplementary table for the completed COREQ assessment for each study.

Table 2.

Comprehensiveness of reporting assessment (Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative studies checklist)25

| Reporting criteria | Number of studies reporting each criterion N=x of 21 |

References of studies reporting each criterion |

|---|---|---|

| Domain 1 | ||

| Characteristics of research team | ||

| Interviewer/facilitator identified | 14 | 30–34 37 38 42 44–49 |

| Credentials | 12 | 29 30 33–35 38–40 42 46 47 49 |

| Occupation | 7 | 34 38–40 42 46 49 |

| Gender | 16 | 30–35 37–39 42 43 45–49 |

| Experience and training | 2 | 38 39 |

| Relationship with participants | ||

| Relationship established before study started | 5 | 34 36 41 44 45 |

| Participant knowledge of the interviewer | 3 | 34 36 41 |

| Interviewer characteristics | 4 | 38 39 42 47 |

| Domain 2 | ||

| Study design | ||

| Methodological theory identified | 15 | 30 32–35 37 38 40 42–45 47–49 |

| Participant selection | ||

| Sampling method (eg, purposive, convenience) | 21 | 29–49 |

| Method of approach | 12 | 32 34 37 38 40–43 45–47 49 |

| Sample size | 21 | 29–49 |

| Number/reasons for non-participation | 7 | 32 34 35 37 40 41 44 |

| Setting | ||

| Setting of data collection | 11 | 29–32 34 36 37 39 41 45 46 |

| Presence of non-participants | 0 | – |

| Description of sample | 17 | 29–34 37–45 47 49 |

| Data collection | ||

| Interview guide | 16 | 29–35 37 38 40–43 46 47 49 |

| Repeat interviews | 0 | – |

| Audio/visual recording | 19 | 30–35 37–49 |

| Field notes | 6 | 30 32 37 40 42 47 |

| Duration | 12 | 30 31 33 35 37 41–45 48 49 |

| Data saturation | 7 | 30 31 35 37–39 44 |

| Transcripts returned to participants | 1 | 44 |

| Domain 3 | ||

| Data analysis | ||

| Number of data coders | 16 | 30–34 36 37 39–42 44–47 49 |

| Description of coding tree | 15 | 30–34 37 39–45 47 49 |

| Derivation of themes | 18 | 30–34 36–47 49 |

| Software | 6 | 30 38 40 44 48 49 |

| Participant checking | 2 | 37 49 |

| Reporting | ||

| Participant quotations presented | 18 | 30–34 37–49 |

| Data and findings consistent | 20 | 29–35 37–49 |

| Clarity of major themes | 18 | 29–34 37–47 49 |

| Clarity of minor themes | 14 | 29–31 33 34 36 37 39–41 43–45 49 |

The lowest rates of reporting were observed in domain 1, meaning that researcher bias (poor confirmability) cannot be excluded.26 Greater transparency was apparent with domains 2 and 3 allowing comparatively better assessment of the credibility, dependability and transferability of study findings. For example, all studies reported the sample size and method and most reported a description of the sample and interview guide. There was consistency between raw data and interpretive findings in all papers except one in which the interpretation was so brief that its accuracy was considered doubtful.36 For five papers, it was unclear whether ethics approval was obtained.29 34 43 44 46

Synthesis of results

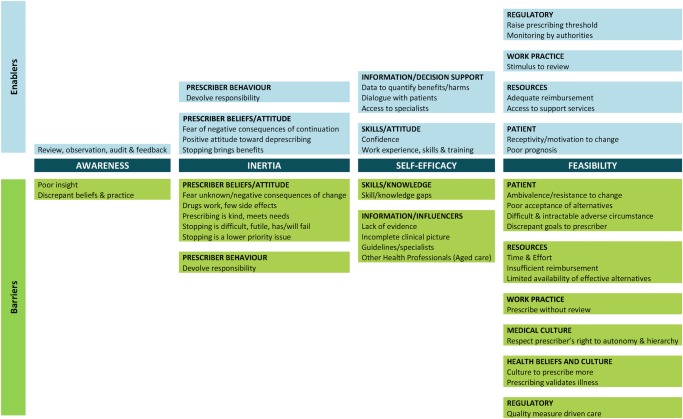

Thematic synthesis yielded 42 subthemes, 12 unique descriptive themes and 4 analytical themes (figure 2), with multiple interdependencies and relationships. Barrier and enabler descriptive themes and subthemes tended to mirror each other for each analytical theme of Awareness, Inertia, Self-efficacy and Feasibility. The first three themes reflect factors intrinsic to the prescriber and his/her decision-making process while the fourth deals with extrinsic factors. Tables 3 and 4 provide illustrative quotations from either primary study participants or study authors relating to barrier and enabler subthemes, respectively.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of barriers and enablers associated with each analytical and descriptive theme.

Table 3.

Illustrative quotations for barrier themes and subthemes

| Analytical and descriptive themes | Subtheme and references | Characteristics of studies from which subthemes were derived Type of PIMs; age focus*; setting (number of references) |

Illustrative quotations “Italicised text”=primary quote (ie, quote from a study participant from an included paper) ‘Non-italicised text’=secondary quote (ie, quote from study authors’ findings from an included paper) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness | |||

| Poor insight46 47 49 | Misc PIMs (3); Older (2) and all ages (1); Primary (2) and secondary care (1) |

“When I saw the list of patients [to be discussed with the researcher], I was quite happy about the prescriptions…but obviously when you look at them in more detail there are anomalies there that ought to be either checked on, reviewed or even altered”46 | |

| Discrepant beliefs and practice31 34 38 41 44 | Benzos (2) and minor opiates (1), Polypharm (1), PPIs (1); Older (1) and all ages (4); Primary care (5) |

‘In contrast to stated beliefs about best practice, physicians estimated that 5–10% of their older adult patients were using benzodiazepines on a daily basis for at least the past 3 months’38 | |

| Inertia | |||

| Prescriber beliefs/attitude | Fear of unknown/negative consequences of change (for the prescriber, patient and staff)29–31 34–36 38 40 42–47 49 | Antidepressants (2), Benzos (2) and minor opiates (1), hypnotics (1), Misc PIMs (4), Polypharm (2), PPIs (2), psychotropics (1); Older (9) and all ages (6); Primary (12), residential aged (2) and secondary (1) care |

“He gets very worried and excitable if you attempt to change anything… even just something minor would cause him virtually a breakdown”46 “We can't predict the effect [of deprescribing] for the individual patient”31 “It's scary to stop a medication that's been going for a long time, because you kind of think am I opening a can of worms here, because I don't know what the reasons were for them starting that medication. To explore all that will take, you know, I can't do all that now, I will have to do that another time”40 “I suggest to them that ideally we should try to get them off of that, but if they're saying, been there, done that, that didn't work for me when I came off of this, I don't think it's worth getting into a big knock-down drag-out [fight] with them or having them leave my practice over this issue”38 |

| Drugs work, few side effects34 35 38 39 41 43–45 47 | Benzos (3) and minor opiates (1), hypnotics (1), Misc PIMs (1), PPIs (2), psychotropics (1); Older (4) and all ages (5); Primary (8) and residential aged (1) care |

‘In their [the physicians’] view psychotropic medication helps the elderly patient remain functional and is the least problematic solution… The physicians stated that they often do not see side effects and that patients often do not report them…’35 | |

| Prescribing is kind, meets needs (of patient, staff, carer)34 37–41 43 44 | Antidepressants (1), Benzos (4) and minor opiates (1), hypnotics (1), PPIs (1); Older (3) and all ages (5); Primary (7) and residential aged (1) care |

“There is a paradox concerning older patients. You do not want to make them grow dull, but on the other hand you know their chronic problems, and you know that at their age the drugs are not so addictive. You want them to keep their minds clear, but on the other hand I do have a tendency to be permissive to older patients”34 “…It treats our own pain as well as our patients’ pain, 'cos we want to help people and make people feel better. So if we give people something and make them feel better, then everybody seems to be happier”39 |

|

| Stopping is difficult, futile has/will fail 31 34 36–38 42 43 46 47 | Antidepressants (1), Benzos (3) and minor opiates (1), hypnotics (1), Polypharm (1), Misc PIMs (2); Older (6) and all ages (3); Primary (7) and residential aged (2) care |

“Let's pretend it’s an octogenarian…if it's gonna make the patient feel better, I don't care if the patient's on it for the rest of their life”38 ‘Most frequent concern identified was the difficulty anticipated in persuading older patients to withdraw after years of using benzodiazepines’36 “In my experience, patients get hooked on PPIs, it is almost addictive like heroin and people appear to experience severe indigestion symptoms on attempting to stop them”44 |

|

| Stopping is a lower priority issue38 40 44 45 49 | Antidepressants (1), Benzos (1), Misc PIMs (1), PPIs (2); Older (3) and all ages (2); Primary (4) and secondary (1) care |

“We are always faced with multiple problems and PPIs are just one issue…”44 | |

| Prescriber behaviour | Devolve responsibility 29 34 35 40–43 49 | Antidepressants (2), Benzos (1) and minor opiates (1), hypnotics (1), Misc PIMs (2), psychotropics (1); Older (5) and all ages (3); Primary (5), secondary (1) and residential aged (2) care |

‘They [the physicians] recognized that the inappropriate use of psychotropic medication for elderly patients was a public health problem, but they felt that it was beyond the scope of the individual physician’35 “(…) I ask them if it should be a sleeping pill or another of the available options and mostly they have a need for sleeping pills”43 “I have been running this practice for twelve years. I took it over from an older colleague. I took over all his patients. They were mostly old people. Prescribing policy has been rather liberal, and I have continued this policy”34 |

| Self-efficacy | |||

| Skills/knowledge | Skills/knowledge gaps30–35 40 45 49 | Antidepressants (1), Benzos and minor opiates (1), Misc PIMs (1), Polypharm (4), PPIs (1), psychotropics (1); Older (7) and all ages (2); Primary (8) and secondary (1) care |

“I don't have enough time for education about the newest information on psychiatric disorders, and better communication with specialists would be very helpful”41 ‘Side effects are not always recognised as such’ 32 “When house officers come on our ward, they haven't necessarily been trained in geriatrics. So they arrive here, and then they start with 10 mg of morphine every four hours. That's too much” (Hospital based geriatrician)49 “You look at the medication list and want to reduce it but then you can't find things you can eliminate”31 |

| Information/influencers | Lack of evidence30 31 33 | Polypharm (3); Older age (3); Primary care (3) |

“To me, the guidelines are kind of a hindrance. At the moment they do not cater for older patients”31 |

| Incomplete clinical picture 30–33 40 41 46 47 49 | Antidepressants (1), Benzos (1), Misc PIMs (3), Polypharm (4); Older (7) and all ages (2); Primary (8) and secondary (1) care |

“The problem is that the medication lists of the doctors involved are not exchanged and are consequently inconsistent”31 “One has discovered that they might have completely different expectations than what the doctor had from the beginning. Do they want to survive for five more years or? And so on. What are their expectations?”30 ‘Medicines, (mainly for chronic conditions) were sometimes not appropriately reviewed because there was no written information on indication and follow-up or because this was not readily available’49 “Sometimes the older people decide for themselves to reduce some of their medication or to adjust the doses without telling their GP. Therefore as their GP you can have the wrong impression about their medication intake…”32 |

|

| Guidelines/specialists30–33 38 44 46 49 | Benzos (1), Misc PIMs (2), Polypharm (4), PPIs (1); Older (6) and all ages (2); Primary (7) and secondary (1) care |

‘When existing guidelines are debated, GPs felt deceived and insecure… The importance of individualising treatment was also expressed and many guidelines were perceived as too rigid leading to a standardized ‘kit’ of medicines per indication…’30 “I have difficulty not following the guidelines if I don't have good reasons to do so”31 “When the hospital consultant recommends a treatment it's difficult… for us not to prescribe unless there is a very good reason. To some extent we feel obliged to carry on when they have initiated it”46 |

|

| Other health professionals (aged care) 42 43 | Antidepressants (1) and hypnotics (1); Older patients (2); Aged care (2) |

“(…) in such a situation it amounts to the sleeping pill, because everybody else's need is the sleeping pill, and I would have to fight tooth and nail if really I wanted to avoid this”43 “They (RACF nurses) called me on the carpet to tell me that withdrawing antidepressants was not a clever thing to do because the patient became angrier and resisted care. They therefore demanded that I reinstate medication”42 |

|

| Feasibility | |||

| Patient | Ambivalence/resistance to change 29–32 35 37 38 40 43 44 46 48 49 | Antidepressants (1), Benzos (2), hypnotics (1), Misc PIMs (4), Polypharm (3), PPIs (1), psychotropics (1); Older (9) and all ages (4); Primary (11), secondary (1) and residential aged (1) care |

“When I said initially we wanted her to come off it, she said, oh no, I’ve been on that for ages, and I don't want to come off it”48 “The discontent rarely lies with the patient themselves”31 |

| Poor acceptance of alternatives37 38 42–44 | Antidepressants (1), Benzos (2), hypnotics (1), PPIs (1); Older (3) and all ages (2); Primary (3) and residential aged (2) care |

“…these types of people and they tend not to want to help themselves, you know they won't take the hypnotherapy and they won't go to yoga classes and they won't do anything else. They just want a quick fix”37 | |

| Difficult and intractable adverse circumstance 34 35 37 39 40 | Antidepressants (1), Benzos (2) and minor opiates (1), psychotropics (1); Older (2) and all ages (3); Primary care (5) |

“I think they have horrible lives, a lot of them… I think it's a combination of all things, their health, their social circumstances… I think a lot of people are on antidepressants because of everything put together. And you can't… change most of the factors that cause it”40 | |

| Discrepant goals to prescriber 30 33 | Polypharm (2); Older age (2); Primary care (2) |

“I kind of get aggravated that half of the medicines that I think are totally rubbish are the ones that the patient really wants to take”33 | |

| Resources | Time and effort30 33 34 37 38 40–42 46 48 49 | Antidepressants (2), Benzos (3) and minor opiates (1), Misc PIMs (3), Polypharm (2); Older (7) and all ages (4); Primary (9), secondary (1) and residential aged (1) care |

“We have a big problem with long-term hypnotic use. It would take an awful lot of work and it's purely a time and work problem”46 |

| Insufficient reimbursement37 38 | Benzos (2); Older (1) and all ages (1); Primary (2) care |

‘A lack time or resources to provide counselling, especially due to the absence of remuneration for doing so’37 | |

| Limited availability of effective alternatives37 38 41–43 | Antidepressants (1), Benzos (3), hypnotics (1); Older (3) and all ages (2); Primary (3) and residential aged (2) care |

‘…There is hardly any alternative to medicamentous therapy’43 | |

| Work practices | Prescribe without review34 35 42 43 45–47 | Antidepressants (1), Benzos and minor opiates (1), hypnotics (1), Misc PIMs (2), PPIs (1), psychotropics (1); Older (4) and all ages (3); Primary (5) and residential aged (2) care |

“(…) then he gets something and he continues this pill, and then the issue is over for him, then it's quiet, and then he has his pill and then he sleeps through, and from time to time you may enquire, it if occurs to you while looking at his medication”43 “When we work in a large health centre, then we sign prescriptions for each other…when a colleague is absent, we issue prescriptions for him that day. Any prescription I issue is my responsibility, but if you are asked to prescribe a particular drug [for a colleague] then you sign it in the reception. I don't check which other drugs that person uses”47 |

| Medical culture | Respect prescriber's right to autonomy and hierarchy 29 30 34 37 45 46 49 | Benzos (1) and minor opiates (1), Misc PIMs (3), Polypharm (1), PPIs (1); Older (2) and all ages (5); Primary (6) and secondary (1) care |

‘The GPs rarely contact colleagues, for example, hospital specialists, as there is a perceived lack of routines for this as well as an informal understanding not to pursue colleagues’ motivations for prescriptions’30 |

| Health beliefs and culture | Culture to prescribe more32 42 47 | Antidepressants (1), Misc PIMs (1), Polypharm (1); Older patients (3), Primary (2) and residential aged (1) care |

“The number of medications grows slowly. There is a complaint, we give new medication, it continues without really stopping it after a while… and it is our responsibility to try and withdraw it from the patient”32 |

| Prescribing validates illness34 40 43 | Antidepressants (1), Benzos and minor opiates (1), hypnotics (1); Older (2) and all ages (1); Primary (2) and residential aged (1) care |

“They feel that unless they are on a tablet for it then they are not having any treatment. There are a lot of those kinds of people”40 | |

| Regulatory | Quality measure driven care33 | Polypharm (1); Older (1); Primary care (1) |

“Another factor that we experience at the VA is these electronic reminders that tell you to do things…What I do really depends on who is in front of me…So the reminder comes up and it makes no sense. This guy's LDL is 101.8… Should I go from 40 to 80 of simvastatin? And what's the risk and benefit there?”33 |

*Age focus refers to the indicative age group of patients who were the focus of participant discussions, as suggested by the terms used in each article, which did not specify the exact age ranges.

Benzos, benzodiazepines; Misc, miscellaneous; PIMs, potentially inappropriate medications; Polypharm, polypharmacy, PPIs, proton pump inhibitors.

Table 4.

Illustrative quotations for enabler themes and subthemes

| Analytical and descriptive themes | Subtheme | Characteristics of studies from which subthemes were derived including: type of PIMs; age focus*; setting (number of references) | Illustrative quotations “Italicised text”=primary quote (ie, quote from a study participant from an included paper) ‘Non-italicised text’=secondary quote (ie, quote from study authors’ findings from an included paper) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness | |||

| Review, observation, audit and feedback 46 47 49 | Misc PIMs (3); Older (2) and all ages (1); Primary (2) and secondary (1) care |

As above46 | |

| Inertia | |||

| Prescriber beliefs/attitude | Fear of negative/unknown consequences of continuation 44 | PPIs (1); All ages (1); Primary care (1) |

“Miracle all right, but too good of anything can be dangerous. Would just like to reiterate that, let me say they [PPIs] even work too well, what worries me is won't there be long-term missed cancers?”44 |

| Positive attitude towards deprescribing31 | Polypharm (1); Older age (1); Primary care (1) |

“You can have a field day with crossing off medication: ‘sure, scrap half of it’”31 | |

| Stopping brings benefits 36 37 48 | Benzos (2) and Misc PIMs (1); Older (2) and all ages (1); Primary care (3) |

“O ya, and she was delighted, I stopped some of her other medications because she was in front of me and I had a bit of time to do it”48 | |

| Prescriber behaviour | Devolve responsibility29 40 44 | Antidepressants (1), Misc PIMs (1), PPIs (1); Older (1) and all ages (2); Primary care (1) |

‘Some [GPs] preferred to wait until the patient went to hospital where they would be taken off their drugs without the GP being blamed. The GP might even write and ask a hospital doctor to do this’29 “Why not be honest and say, the NHS can't afford to keep giving you these drugs unless there's a very good reason. The patients understand that, and in this day and age they understand perfectly well about cost”44 |

| Self-efficacy | |||

| Skills/attitude | Confidence (to stop therapy/deviate from guidelines)33 45 | Polypharm (1), PPIs (1); Older patients (1) and all ages (1); Primary care (2) |

“It's not as if the life of the patient is suddenly at risk because I take away a pill, yes. […] in the worst case heartburn may re-occur or there is upper abdominal discomfort, but that will not immediately cause a bleeding ulcer”45 “I sort of you know tone those goals down. I am not looking for a Hemaglobin A1C of 7 anymore…so I take the pressure off them and I start removing those medications especially the ones that cause hypoglycaemia”33 |

| Work experience, skills and training30 45 49 | Misc PIMs (1), Polypharm (1), PPIs (1); Older (2) and all ages (1); Primary (2) and secondary (1) care |

“Yes, maybe problem oriented when you are new. Maybe now one thinks more about consequences, in another way”30 | |

| Information/decision support | Data to quantify benefits/harms30–32 48 | Misc PIMs (1), Polypharm (3); Older (4); Primary care (4) |

“Because actually what you could do is to give him (patient) some more ‘hard core’ facts like: ‘If you refrain from treatment your chance of stroke is 20%…”30 |

| Dialogue with patients29 30 31 44 46 | Misc PIMs (2), Polypharm (2), PPIs (1); Older (2) and all ages (3); Primary care (5) |

‘Discussion during the research interview made some patients more willing to consider a change in medication’29 ‘Adequate discussion with patients was widely recognised as one of the keys to influencing change, but although practiced by some GPs it was not always successful’46 |

|

| Access to specialists 40 41 44 49 | Antidepressants (1), Benzos (1), Misc PIMs (1), PPIs (1); Older (2) and all ages (2); Primary (3) and secondary (1) care |

‘They (low benzodiazepine prescribing family physicians) desired better co-operation and clear instructions from psychiatrists’ 41 | |

| Feasibility | |||

| Patient | Receptivity/motivation to change 33 37 46 | Benzos (1), Misc PIMs (1), Polypharm (1); Older (1) and all ages (2); Primary care (3) |

“He’s fairly amenable to tinkering with his pills, so we'll look at that”46 |

| Poor prognosis49 | Misc PIMs (1); Older age (1); Secondary care (1) |

“Sometimes people have taken 10 medicines while they were in curative care, and gradually they move on to palliative care. Then we must reconsider all the prescriptions, drug by drug, saying: OK, what's the goal? To improve your comfort? Well, this medicine will make you feel more comfortable; we can stop this other one”49 | |

| Resources | Adequate reimbursement 38 | Benzos (1); Older age (1); Primary care (1) |

“Reimbursement is very low…I think if it was something that we did get reimbursed on I think you would see physicians’ attitudes a lot different. You'd be more willing to spend time”38 |

| Access to support services31 37 41 46 | Benzos (2), Polypharm (1), Misc PIMs (1); Older (1) and all ages (3); Primary care (4) |

‘Most GPs work closely with a local pharmacist [when undertaking medication review to stop medicines]: the task perception of such pharmacists was an important factor when a GP was looking for decision support in medication review’31 | |

| Work practice | Stimulus to review29 31 40 44 48 49 | Antidepressants (1), Misc PIMs (3); Polypharm (1), PPIs (1); Older (4) and all ages (2); Primary (5) and secondary (1) care |

‘A new patient entering the practice list is welcomed as an opportunity to review their medication’31 |

| Regulatory | Raise the prescribing threshold 44 45 | PPIs (2); All ages (2); Primary care (2) |

“I think we are all sitting here and debating about this mainly because of the pressure on us by our pharmaceutical advisors not to prescribe PPIs because of cost implications to the NHS; I bet that this will not be an important topic in 2 years when Losec goes generic”44 |

| Monitoring by authorities 34 | Benzos and minor opiates (1); All ages (1); Primary care (1) |

‘The continuous monitoring of prescriptions by health authorities also put stress on the doctors’34 | |

*Age focus refers to the indicative age group of patients who were the focus of participant discussions, as suggested by the terms used in each article, which did not specify the exact age ranges.

Benzos, benzodiazepines; Misc, miscellaneous; PIMs, potentially inappropriate medications; Polypharm, polypharmacy; PPIs, proton pump inhibitors.

Fewer enablers were reported than barriers and there was variation in the relative contribution of each study to each theme.

Awareness

Awareness refers to the level of insight a prescriber has into the appropriateness of his/her prescribing. This theme was apparent in the three papers which utilised audit or informal third-party (eg, other health professional) observation and feedback.46 47 49 Poor insight was an observed rather than reported barrier, with interventions to raise prescriber awareness an enabler to minimising the prescription of PIMs. Prescriber beliefs at a population level did not necessarily translate to prescribing practices at an individual level. For example, agreement among prescribers that benzodiazepines should not be used regularly or in the long term did not necessarily preclude such prescribing in individual patients.34 38 41

Inertia

Inertia is defined as the failure to act, despite awareness that prescribing is potentially inappropriate, because ceasing PIMs is perceived to be a lower value proposition than continuing PIMs.

Fear of unknown/negative consequences of change featured in 15 of 22 papers, and related to consequences for: the prescriber (threatened therapeutic relationship, diminished credibility, increased initial and ongoing workload, potential for litigation, conflict with other prescribers/health professionals)29–31 34–36 38 40 43–47 49; the patient (withdrawal syndrome, symptom relapse or increased risk of the condition/event for which preventive medication was originally prescribed)36 38 40 42–47 and other health professionals (increased workload and safety concerns of staff in RACFs).42 43 The prescriber beliefs that facilitate cessation were the converse, that is, fear of unknown/negative consequences of continuation,44 a positive attitude to stopping medicines31 and a belief that this practice can bring benefits.36 37 48

The barrier belief that drugs appear to work with few adverse effects was apparent in nine papers34 35 38 39 41 43–45 47 of which two studied ‘high-rate’ and ‘low-rate’ benzodiazepine prescribers. ‘High-rate’ prescribers consistently downplayed risks of harm, whereas ‘low/ medium-rate’ prescribers were more conscious of such risks.34 41 The futility and potential harm of cessation in patients of advanced age was a subtheme predominantly present in papers considering psychoactive agents.34 35 38 43 46 47

Another barrier was the devolvement of responsibility to another party for the decision to continue or cease a medication (eg, another prescriber, health professional, society or the patient). One example was continuation of PIMs in patients that prescribers had inherited from colleagues where the former failed to question the rationale used by the latter in prescribing such drugs.29 34 41 49 Another example was the provision of PIMs on the request of RACF nursing staff42 or patients34 40 43 without a critical prescriber review. Finally, inappropriate prescribing of psychotropics, while viewed as a public health concern, was considered beyond the scope of individual prescribers.35

Self-efficacy

This analytical theme refers to factors that influence a prescriber's belief and confidence in his or her ability to address PIM use. It involves subthemes relating to knowledge, skill, attitudes, influences, information and decision support.

Knowledge or skill deficits,30–35 40 45 49 including difficulty in balancing the benefits and harms of therapy,30–33 recognising adverse drug effects31 32 and establishing clear-cut diagnoses/indications for medicines,34 35 40 were challenges prescribers faced in identifying and managing PIMs. Balancing the benefits and harms was perceived to be especially difficult when reviewing preventive medications in multimorbid older people with polypharmacy where shorter life expectancy, uncertain future benefits and higher susceptibility to more immediate adverse drug effects must all be considered.30–33 On the other hand, better quantification of the benefits and harms of therapy,30–32 48 confidence to deviate from guidelines and stop medications if thought necessary,33 45 greater experience,30 45 and targeted training, especially in prescribing for older people,49 were seen as enabling factors.

Compounding generic knowledge and skill gaps were information deficits specific to individual prescribing decisions, resulting from poor communication with multiple prescribers and specialists involved in patient care, inadequate transfer of information at care interfaces, fragmented and difficult-to-access patient medical records, and failure of patients to know/disclose their full medical history/medication lists to prescribers.30–33 40 41 46 47 49 This subtheme linked strongly with time and effort demands on prescribers, and in two papers was associated with low motivation arising from a perceived inability to efficiently access all information required for optimal prescribing.40 49

Eight papers discussed the influence of care recommendations from guidelines and specialists.30–33 38 44 46 49 Guidelines were often viewed negatively, with prescribers feeling pressured to comply with recommendations at odds with the complexities of clinical practice.30–32 44 46 Pressure from staff to continue prescribing PIMs, often to maintain facility routines, was presented as a barrier unique to RACFs.42 43 Offsetting this were enablers centred on greater dialogue with patients to increase understanding and facilitate shared decision-making,29 30 31 44 46 as well as timely access to, and decision support from, specialists, particularly geriatricians and psychiatrists.37 40 41 44 46 49

Feasibility

Feasibility refers to factors, external to the prescriber, which determine the ease or likelihood of change. They relate to patient characteristics, resource availability, work practices, medical and societal health beliefs and culture, and regulations.

The most frequently expressed barrier concerning patients was their ambivalence or resistance to change29–32 35 37 38 40 43 44 46 48 49 and their poor acceptance of alternative therapies.37 38 42–44 In contrast, receptivity and capacity to change were identified as enablers in three studies,33 37 46 as was a poor prognosis which helped crystallise care goals and prompt review of the appropriateness of existing drug regimens.49

The limited time and effort to review and discontinue medications30 33 34 37 38 40–42 46 48 49 was the most common resource constraint followed by the limited availability of effective non-drug treatment options.35 37 38 41–43 Adequate reimbursement38 and access to support services such as mental health workers and pharmacists for medication review31 37 41 46 emerged as enablers.

Certain work practices were raised as barriers to deprescribing, such as provision of repeats for a prescriber's own or colleague's patients,34 46 47 and the absence of explicit treatment plans or a formal or scheduled medication review.34 43 The mirroring enablers were opportunities to review medication regimens (eg, hospital admission,29 49 change of prescriber,31 specialist40 or scheduled review).44 48

The remaining descriptive themes related to medical and societal health beliefs and cultural and regulatory factors. The most frequently mentioned barrier was discomfort and reluctance to question a colleagues’ prescribing decisions29 30 34 37 45 46 49 associated with respect for professional autonomy or the medical hierarchy when specialist prescribers were involved.

Externally imposed guideline-based quality measures were presented as a barrier to minimising the prescription of PIMs.33 Raising the prescribing threshold for medications (eg, through increased cost or restricted access)44 45 and monitoring by authorities34 were seen by prescribers as unwelcome, perverse enablers.

Discussion

This systematic review comprehensively investigates prescriber barriers and enablers to minimising the prevalence of chronically prescribed PIMs in adults. The thematic construct which was developed from published literature centres on Awareness, Inertia, Self-efficacy and Feasibility. It principally reflects the perspectives of primary care physicians managing older, community-based adults. Although the themes and subthemes have been presented separately, the reasons doctors continue to prescribe, or do not cease, PIMs are multifactorial, highly interdependent and impacted by considerable clinical complexity.

Many subthemes were common to papers regardless of interstudy differences in the PIMs discussed, patient age and clinical setting (eg, primary, secondary or residential aged care).

Subthemes varied according to whether studies focused on polypharmacy or single PIMs or classes of PIMs, which were also associated with differing levels of prescriber insight and certainty. In the four studies focused on polypharmacy, prescribers were aware of polypharmacy-related harm but could not easily identify which medications were inappropriate, as reflected by the subthemes ‘difficulty/inability to balance benefits and harms of therapy’,30–33 ‘inability to recognise adverse drug effects’,31 32 ‘lack of evidence’30 31 33 and ‘incomplete clinical picture’.30–33 In other studies focusing on specific classes of overprescribed medications, prescribers were aware of this inappropriateness, but in response voiced various rationalisations for continued prescribing such as ‘drugs work, few adverse effects’,34 35 38 39 41 43–45 47 ‘prescribing is kind and meets needs’,34 37–41 43 44 ‘stopping is difficult, futile, has or will fail’,34 36–38 42 43 47 ‘poor (patient) acceptance of alternatives’,37 38 42–44 and ‘difficult and intractable adverse (patient) circumstance’.34 35 37 39 40

However, in other studies focusing on miscellaneous PIMs, prescribers were generally not aware of their inappropriate prescribing until this was revealed to them (eg, through audit and feedback).46 47 49

No definite thematic pattern was observed from the subthemes of six studies which did not specifically focus on the care of older people29 37 39 41 44 45 compared with the remaining 15 which did. Compared with studies in primary care, unique themes emerged from papers set in RACFs and acute care settings. For example, pressure on prescribers to continue prescribing PIMs at the request of RACF nursing staff was unique to this setting.42 43 The one study set in acute care highlighted inexperience and training deficiencies of junior prescribers, as viewed by three geriatricians.49

The finding that poor insight into potentially inappropriate prescribing (PIP) practices was only apparent in studies where prescribers were made aware of this is unsurprising given that prescribers do not intentionally prescribe medications inappropriately. It demonstrates the importance of awareness-raising strategies for prescribers. Inertia, as in failure to deprescribe when appropriate, sits at odds with the more traditional use of the word as symbolising failure to intensify therapy when indicated.50 Inertia has been linked to ‘omission bias’ where individuals deem harm resulting from an act of commission to be worse than that resulting from an act of omission.51 52 In the case of deprescribing as an act of commission, it becomes more a matter of reconciling a level of expected utility (accrual of benefits) with a level of acceptable regret (potential to cause some harm).53 Fear of negative consequences resulting from deprescribing contributes to inertia and is not easily allayed by the current limited evidence base regarding the safety and efficacy of deprescribing.54 In the same papers in which prescribers rationalised continuation of therapy with the belief that drugs work and have few adverse effects,34 35 38 39 41 43–45 47 prescribers also identified different thresholds for initiating versus continuing the same therapy. This anomaly suggests a lack of prescriber insight, clear differences in prescribers’ attitudes towards initiation versus continuation, or a social response bias towards a false belief induced by the methodology used by interviewers.

Relevance to previous literature

One meta-synthesis of seven papers has recently been published online exploring prescribers’ perspectives of why PIP occurs in older people.55 Compared with our review, this study had a generic focus on PIP, including underprescribing, and its search strategy retrieved fewer articles (n=7). Scanning their reference list did not reveal any additional papers which would have met our selection criteria and their results yielded no additional themes.

Our findings are consistent with those in the literature (largely focused on initiation of therapy), suggesting that pharmacological considerations are not the only factors impacting doctors' prescribing decisions.56 Interacting clinical, social and cultural factors relating to both the patient and prescriber influence prescribing decisions.56–58

Reeve et al20 recently published a review of patient barriers and enablers to deprescribing and have emphasised the importance of a patient-centred deprescribing process.59 When comparing their results with ours, we find that prescribers’ barriers are concordant with those of patients with respect to resistance to change, poor acceptance of non-drug alternatives, and fear of negative consequences of discontinuation. However, prescribers also underestimate enabling factors including patients’ experiences/concerns of adverse effects, dislike of multiple medicines, and being assured that a ceased medication can be recommenced if necessary. Patients also reported that their primary care physician could be highly influential in encouraging them to discontinue therapy, a perception not echoed among prescribers in this review.20 Prescribers need to discuss, rather than assume, patient attitudes towards their medicines and to deprescribing, in the context of their current care goals.

Previous reviews of interventions to reduce inappropriate prescribing/polypharmacy in older patients have not been able to conclude with certainty that multifaceted interventions are more effective than single strategies.60 61 Although our findings suggest that the former are likely to be more successful, further research is required to identify the barriers and enablers with the greatest potential for impact in designing targeted deprescribing interventions.

Strengths and limitations

Inconsistent terminology and poor indexing of search terms relating to deprescribing and inappropriate therapy greatly hampered our ability to identify relevant studies. Our mitigation efforts comprised a comprehensive prescoping exercise, a highly iterative search strategy tailored to each database, and snowballing from reference lists and related citations.

Despite no search restrictions on patient age, clinical setting or type of PIM, most study participants were experienced primary care physicians caring for older, community-based adults. Caution is therefore needed when transferring our results to other settings or patient groups. However, two recent cross-sectional studies looking at barriers to discontinuation of benzodiazepines and antipsychotics in nursing homes reflected subthemes identified in our review—fear of negative consequences of discontinuation such as poorer quality of life, symptom recurrence, greater workload and a lack of available, effective, non-drug alternatives.62 63

Many of the papers focused on relatively few drug classes (psychotropics and PPIs) and only four focused on polypharmacy. Although some subthemes were common to all types of studies (single and miscellaneous PIMs and polypharmacy papers), others were not. It is possible that, had more medication classes been studied, some of our results may have been different.

The strengths of our review include adherence to a peer-reviewed, documented methodology for thematic synthesis, COREQ assessment of studies allowing the assessment of potential for bias, compliance with ENTREQ reporting requirements and a multidisciplinary team of investigators to validate theme identification and synthesis.

Implications for clinicians and policymakers and future research

The results of this review disclose prescriber perceptions of their own cognitive processes as well as patient, work setting and other health system factors which shape their behaviour towards continuing or discontinuing chronically prescribed PIMs. The thematic synthesis provides a clear conceptual framework to understand this behaviour. Rendering these issues visible for both clinicians and policymakers is the first stage in minimising inappropriate prescribing in routine clinical practice. It facilitates what has been lacking in deprescribing intervention studies to date—a pragmatic approach towards identifying and accounting for local barriers and enablers which will determine the overall effectiveness of targeted interventions.

Further high-quality prospective clinical trials are urgently needed in demonstrating the safety, benefits and optimal modes of deprescribing, especially in relation to multimorbid older people.61 64 The fog of polypharmacy clouds a prescriber's capacity and confidence to identify PIMs which, to be overcome, requires complete and accurate clinical information and decision support.

Professional organisations and colleges have an important role in encouraging the necessary cultural and attitudinal shifts towards ‘less can be more’ in appropriate patients. The push for guideline adherence and intensification of therapy needs to be counterbalanced by the view that judicious reduction, discontinuation or non-initiation of medication, in the context of shared decision-making and agreed care goals, is an affirmation of highest quality, individualised care.65 This view needs to be embraced in the education and training of all health professionals, not just doctors, who influence the prescribing process.

Prescribers are making decisions in the face of immense clinical and health system complexity. Appropriate deprescribing needs to be regarded as equally important and achievable as appropriate initiation of new medications. Understanding how prescribers perceive and react to prescribing and deprescribing contexts is the first step to designing policy initiatives and health system reforms that will minimise inappropriate overprescribing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the University of Queensland librarians Mr Lars Eriksson and Ms Jill McTaggart for their assistance in developing the search strategy and Ms Debra Rowett for her invaluable insights when scoping the search and developing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: IS conceived the paper, the scope of which was refined by all authors. KA searched the literature, led the data analysis and drafted the manuscript. IS and DS read articles and assessed the data analysis for comprehensiveness and reliability. IS, DS and CF provided critical comments and contributed to the interpretation of the analysed results and framework development. All authors read, revised and accepted the final draft.

Funding: KA and IS are funded through a National Health and Medical Research Council grant under the Centre of Research Excellence Quality & Safety in Integrated Primary/Secondary Care (Grant ID, GNT1001157).

Competing interests: KA received a speaker honorarium for an Australian Association of Consultant Pharmacy presentation. DS reports personal fees from the National Prescribing Service, outside the submitted work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data used to develop the tables and figures presented in this article are available by emailing the corresponding author, Kristen Anderson, k.anderson8@uq.edu.au.

References

- 1.Morgan T, Williamson M, Pirotta M et al. A national census of medicines use: a 24-hour snapshot of Australians aged 50years and older. Med J 2012;196:50–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qato DM, Alexander G, Conti RM et al. Use of prescription and over-the-counter medications and dietary supplements among older adults in the united states. JAMA 2008;300:2867–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Price SD, Holman CD, Sanfilippo FM et al. Are older Western Australians exposed to potentially inappropriate medications according to the Beers Criteria? A 13-year prevalence study. Australas J Ageing 2014;33:E39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guaraldo L, Cano FG, Damasceno GS et al. Inappropriate medication use among the elderly: a systematic review of administrative databases. BMC Geriatr 2011;11:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aparasu R, Mort J. Inappropriate prescribing for the elderly: beers criteria-based review. Ann Pharmacother 2000;34:338–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Opondo D, Eslami S, Visscher S et al. Inappropriateness of medication prescriptions to elderly patients in the primary care setting: a systematic review. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e43617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roughead EE, Anderson B, Gilbert AL. Potentially inappropriate prescribing among Australian veterans and war widows/widowers. Intern Med J 2007;37:402–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byles JE, Heinze R, Nair BK et al. Medication use among older Australian veterans and war widows. Intern Med J 2003;33:388–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stafford AC, Alswayan MS, Tenni PC. Inappropriate prescribing in older residents of Australian care homes. J Clin Pharm Ther 2011;36:33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Somers M, Rose E, Simmonds D et al. Quality use of medicines in residential aged care. Aust Fam Physician 2010;39:413–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cahir C, Bennett K, Teljeur C et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing and adverse health outcomes in community dwelling older patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2014;77:201–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dedhiya SD, Hancock E, Craig BA et al. Incident use and outcomes associated with potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2010;8:562–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalisch LM, Caughey GE, Barratt JD et al. Prevalence of preventable medication-related hospitalizations in Australia: an opportunity to reduce harm. Int J Qual Health Care 2012;24:239–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carey IM, De Wilde S, Harris T et al. What factors predict potentially inappropriate primary care prescribing in older people? Analysis of UK primary care patient record database. Drugs Aging 2008;25:693–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lai HY, Hwang SJ, Chen YC et al. Prevalence of the prescribing of potentially inappropriate medications at ambulatory care visits by elderly patients covered by the Taiwanese National Health Insurance program. Clin Ther 2009;31:1859–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meurer WJ, Potti TA, Kerber KA et al. Potentially inappropriate medication utilization in the emergency department visits by older adults: analysis from a nationally representative sample. Acad Emerg Med 2010;17:231–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alldred DP. Deprescribing: a brave new word? Int J Pharm Pract 2014;22:2–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organisation. Guide to Good Prescribing—A Practical Manual. Chapter 11. STEP 6: Monitor (and stop?) the treatment 1994.

- 19.NPS: Better Choices BH. Competencies required to prescribe medicines: putting quality use of medicines into practice. Sydney: National Prescribing Service Limited, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reeve E, To J, Hendrix I et al. Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing: a systematic review. Drugs Aging 2013;30:793–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dixon-Woods M, Bonas S, Booth A et al. How can systematic reviews incorporate qualitative research? A critical perspective. Qual Res 2006;6:27–44. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E et al. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mays N, Pope C, Popay J. Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy-making in the health field. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10(Suppl 1):6–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.InterTASC Information Specialists’ Sub-Group. Filters to Identify Qualitative Research. Secondary Filters to Identify Qualitative Research. https://sites.google.com/a/york.ac.uk/issg-search-filters-resource/filters-to-identify-qualitative-research

- 25.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hannes K. Chapter 4: Critical appraisal of qualitative research. In: Noyes J, Booth A, Hannes K, et al., eds. Supplementary Guidance for Inclusion of Qualitative Research in Cochrane Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 1 (updated Aug 2011). Cochrane Collaboration Qualitative Methods Group, 2011. http://cqrmg.cochrane.org/supplemental-handbook-guidance [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tong A, Lesmana B, Johnson DW et al. The perspectives of adults living with peritoneal dialysis: thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Am J Kidney Dis 2013;61:873–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Britten N, Brant S, Cairns A et al. Continued prescribing of inappropriate drugs in general practice. J Clin Pharm Ther 1995;20:199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moen J, Norrgard S, Antonov K et al. GPs’ perceptions of multiple-medicine use in older patients. J Eval Clin Pract 2010;16:69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schuling J, Gebben H, Veehof LJG et al. Deprescribing medication in very elderly patients with multimorbidity: the view of Dutch GPs. A qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract 2012;13:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anthierens S, Tansens A, Petrovic M et al. Qualitative insights into general practitioners views on polypharmacy. BMC Fam Pract 2010;11:65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fried TR, Tinetti ME, Iannone L. Primary care clinicians’ experiences with treatment decision making for older persons with multiple conditions. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:75–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dybwad TB, Kjolsrod L, Eskerud J et al. Why are some doctors high-prescribers of benzodiazepines and minor opiates? A qualitative study of GPs in Norway. Fam Pract 1997;14:361–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Damestoy N, Collin J, Lalande R. Prescribing psychotropic medication for elderly patients: some physicians’ perspectives. CMAJ 1999;161:143–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iliffe S, Curran HV, Collins R et al. Attitudes to long-term use of benzodiazepine hypnotics by older people in general practice: findings from interviews with service users and providers. Aging Ment Health 2004;8:242–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parr JM, Kavanagh DJ, Young RM et al. Views of general practitioners and benzodiazepine users on benzodiazepines: a qualitative analysis. Soc Sci Med 2006;62:1237–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cook JM, Marshall R, Masci C et al. Physicians’ perspectives on prescribing benzodiazepines for older adults: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:303–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rogers A, Pilgrim D, Brennan S et al. Prescribing benzodiazepines in general practice: a new view of an old problem. Health (London) 2007;11:181–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dickinson R, Knapp P, House AO et al. Long-term prescribing of antidepressants in the older population: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract 2010;60:e144–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Subelj M, Vidmar G, Svab V. Prescription of benzodiazepines in Slovenian family medicine: a qualitative study. Wiener klinische Wochenschrift 2010;122:474–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iden KR, Hjorleifsson S, Ruths S. Treatment decisions on antidepressants in nursing homes: a qualitative study. Scand J Prim Health Care 2011;29:252–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Flick U, Garms-Homolová V, Röhnsch G. “And mostly they have a need for sleeping pills”: physicians’ views on treatment of sleep disorders with drugs in nursing homes. J Aging Stud 2012;26:484–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raghunath AS, Hungin APS, Cornford CS et al. Use of proton pump inhibitors: an exploration of the attitudes, knowledge and perceptions of general practitioners. Digestion 2005;72:212–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wermeling M, Himmel W, Behrens G et al. Why do GPs continue inappropriate hospital prescriptions of proton pump inhibitors? A qualitative study. Eur J Gen Pract 2013;20:174–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cantrill JA, Dowell J, Roland M. Qualitative insights into general practitioners’ views on the appropriateness of their long-term prescribing. Int J Pharm Pract 2000;8:20–6. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frich JC, Hoye S, Lindbaek M et al. General practitioners and tutors’ experiences with peer group academic detailing: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract 2010;11:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clyne B, Bradley MC, Hughes CM et al. Addressing potentially inappropriate prescribing in older patients: development and pilot study of an intervention in primary care (the OPTI-SCRIPT study). BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spinewine A, Swine C, Dhillon S et al. Appropriateness of use of medicines in elderly inpatients: qualitative study. BMJ 2005;331:935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ostini R, Hegney D, Jackson C et al. Knowing how to stop: ceasing prescribing when the medicine is no longer required. J Manag Care Pharm 2012;18:68–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ritov I, Baron J. Status-quo and omission biases. J Risk Uncertainty 1992;5:49–61. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spranca M, Minsk E, Baron J. Omission and commission in judgment and choice. J Exp Soc Psychol 1991;27:76–105. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsalatsanis A, Hozo I, Vickers A et al. A regret theory approach to decision curve analysis: a novel method for eliciting decision makers’ preferences and decision-making. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2010;10:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I et al. The benefits and harms of deprescribing. Med J Aust 2014;201:386–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cullinan S, O'Mahony D, Fleming A et al. A meta-synthesis of potentially inappropriate prescribing in older patients. Drugs Aging 2014;31:631–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bradley CP. Factors which influence the decision whether or not to prescribe: the dilemma facing general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract 1992;42:454–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Butler CC, Rollnick S, Pill R et al. Understanding the culture of prescribing: qualitative study of general practitioners’ and patients’ perceptions of antibiotics for sore throats. BMJ 1998;317:637–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cohen D, McCubbin M, Collin J et al. Medications as social phenomena. Health 2001;5:441–69. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I et al. Review of deprescribing processes and development of an evidence based, patient-centred deprescribing process. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2014;78:738–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kaur S, Mitchell G, Vitetta L et al. Interventions that can reduce inappropriate prescribing in the elderly. Drugs Aging 2009;26:1013–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Patterson S, Hughes C, Kerse N et al. Interventions to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy for older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;5:CD008165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Azermai M, Vander Stichele RRH, Van Bortel LM et al. Barriers to antipsychotic discontinuation in nursing homes: an exploratory study. Aging Ment Health 2014;18:346–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bourgeois J, Elseviers MM, Azermai M et al. Barriers to discontinuation of chronic benzodiazepine use in nursing home residents: perceptions of general practitioners and nurses. Eur Geriatr Med 2013;5:181–7. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Iyer S, Naganathan V, McLachlan A et al. Medication withdrawal trials in people aged 65 years and older. Drugs Aging 2008;25: 1021–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Scott I, Anderson K, Freeman C et al. First do no harm: a real need to deprescribe in older patients. Med J Aust 2014;201:309–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.