Abstract

Objectives

Headaches are a common medical problem, yet few studies, particularly trials, have evaluated therapies that might prevent or control headaches. We, thus, investigated the effects on the occurrence of headaches of three levels of dietary sodium intake and two diet patterns (the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet (rich in fruits, vegetables and low-fat dairy products with reduced saturated and total fat) and a control diet (typical of Western consumption patterns)).

Design

Randomised multicentre clinical trial.

Setting

Post hoc analyses of the DASH-Sodium trial in the USA.

Participants

In a multicentre feeding study with three 30 day periods, 390 participants were randomised to the DASH or control diet. On their assigned diet, participants ate food with high sodium during one period, intermediate sodium during another period and low sodium during another period, in random order.

Outcome measures

Occurrence and severity of headache were ascertained from self-administered questionnaires, completed at the end of each feeding period.

Results

The occurrence of headaches was similar in DASH versus control, at high (OR (95% CI)=0.65 (0.37 to 1.12); p=0.12), intermediate (0.57 (0.29 to 1.12); p=0.10) and low (0.64 (0.36 to 1.13); p=0.12) sodium levels. By contrast, there was a lower risk of headache on the low, compared with high, sodium level, both on the control (0.69 (0.49 to 0.99); p=0.05) and DASH (0.69 (0.49 to 0.98); p=0.04) diets.

Conclusions

A reduced sodium intake was associated with a significantly lower risk of headache, while dietary patterns had no effect on the risk of headaches in adults. Reduced dietary sodium intake offers a novel approach to prevent headaches.

Trial registration number

Keywords: Headache, Sodium, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension, DASH-Sodium trial

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Post hoc analysis of a multicentre randomised clinical trial comparing effects of the two diet patterns using parallel design together with a three-period crossover of three levels of dietary sodium (high (150 mmol), intermediate (100 mmol), low (50 mmol)) on headaches in healthy adults with stage 1 hypertension.

Three screening and two run-in feeding periods prior to randomisation to assess participant's eligibility, compliance with dietary requirements and to estimate caloric requirements to maintain weight during study.

Vigorous efforts made to promote adherence with assigned diets during feeding periods.

Lack of information on the prevalence of headaches at baseline as well as type of self-reported headaches experienced by participants at the end of feeding periods.

Introduction

Worldwide, headache is a common medical problem and among the most frequently reported disorders of the nervous system.1–3 Globally, 46% of adults are estimated to have an active headache disorder (42% for tension-type headaches; 11% for migraines).2 4–6 Headaches affect all age groups, with a higher prevalence in women compared with men.4–6 The direct cost of healthcare services, and medications for the management of headaches is likewise substantial,7–11 as are indirect costs. Patients with frequent headaches have a poor quality of life and a higher number of days absent from work, compared with others.12–15 Hence, successful strategies to prevent and treat headache would confer substantial benefits to afflicted individuals, as well as to society in general.

Available data support a direct association between blood pressure and the occurrence of headache.16–19 Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that dietary factors that lower blood pressure (eg, reduced sodium intake and the DASH diet20 21) might also reduce the occurrence of headache. However, evidence on the relationship of headaches with sodium intake and other dietary factors is sparse, with most attention focusing on the potential role of monosodium glutamate intake.22–24 In the primary results paper of the DASH-Sodium trial, which focused on the blood pressure effects of the dietary interventions, the authors briefly comment on the occurrence of headaches in the broad context of side effects. They reported that the side effect of headache occurred in 47% of participants during the high, compared with 39 percent during the low, sodium feeding period.21 In this paper, we expand on these preliminary observations.

Methods

A detailed description of the rationale, design and methods of the DASH-Sodium trial has been published.25 Briefly, DASH-Sodium was a multicentre, randomised clinical trial, conducted between September 1997 and November 1999, designed to compare the effects on blood pressure of three levels of dietary sodium and two diet patterns. The study design incorporated a parallel, two-group, comparison of diet (DASH diet vs control diet) together with a three-period crossover of the three levels of dietary sodium intake, with a primary outcome of mean systolic blood pressure (figure 1). The three sodium levels were (1) ‘high’ (150 mmol, at 2100 kcal caloric intake), reflecting average consumption in the USA, (2) ‘intermediate’ (100 mmol) reflecting the upper limit of current recommendations for adults26 and (3) ‘low’ (50 mmol). The DASH diet is rich in fruits, vegetables and low-fat dairy products; high in dietary fibre, potassium, calcium and magnesium; moderately high in protein; and low in saturated fat, cholesterol and total fat. The control diet is typical of what many in the Western world eat.

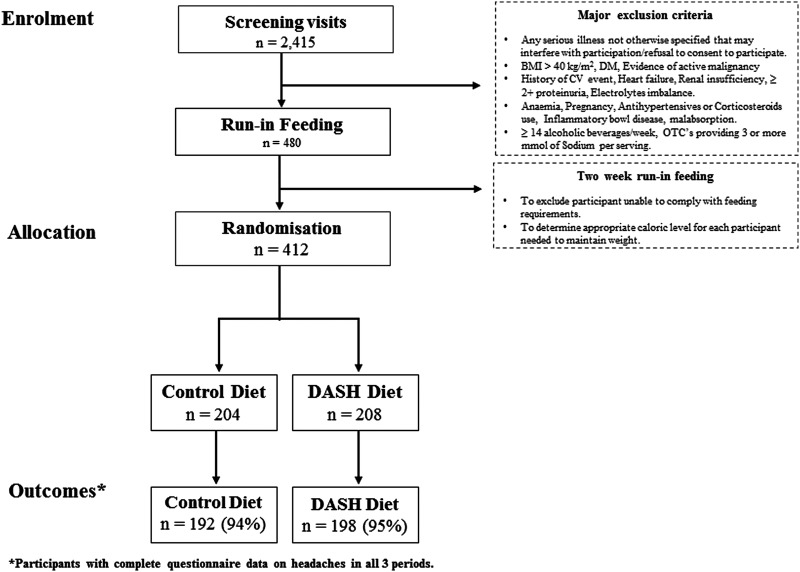

Figure 1 .

DASH -Sodium trial flow diagram (BMI, body mass index; CV, cardiovascular; DM, diabetes mellitus; OTC, over the counter).

Study participants were 412 adults (age ≥22 years) with systolic blood pressure between 120 and 159 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure between 80 and 95 mm Hg (ie, prehypertension or stage 1 hypertension). Major exclusion criteria were diabetes mellitus, evidence of active malignancy, history of cardiovascular event (angina, myocardial infarction, angioplasty or stroke), renal insufficiency (serum creatinine >1.2 mg/dL for females or 1.5 mg/dL for males), anaemia (haematocrit at least 5% below normal range), pregnancy, inflammatory bowel disease, body mass index (BMI) >40 kg/m2, use of antihypertensive drugs and corticosteroids, and consumption of more than 14 alcoholic beverages per week.

Three screening visits (each separated by at least 7 days) were conducted to assess general eligibility and to collect baseline data. Following the screening visits, eligible participants started a 2-week run-in feeding period during which they ate the control diet at the high sodium level. The run-in feeding period was designed to exclude participants who were unlikely to comply with the dietary requirements and to estimate caloric requirements needed to maintain weight. Participants were then randomly assigned (generated using desktop PC at each coordinating centre) to one of the two diets using a parallel-group design, and ate each of three sodium levels (feeding periods) for 30 days each, in a randomised crossover design. Participants were not notified of their assigned dietary pattern or sodium sequence.

During feeding periods (run-in and intervention), participants were required to eat at least one meal per day on site at the clinical centre, 5 days per week, and to take food home for other meals. Participants were expected to eat all of their food and were instructed to record the type and amount of any uneaten study food. Caffeinated beverages and alcohol were limited and monitored. Individual energy intake (calorie content) was adjusted, so that each participant’s weight during each feeding period remained stable.

Data collection staff were masked to randomised sodium and diet sequence. Measurements were obtained during screening and at the end of each feeding period. Blood pressure was measured in a seated position, using the right arm of participants. Twenty-four hour urine (for analysis of sodium, potassium, urea nitrogen and creatinine) and body weight were also collected. Compliance with the feeding protocol was assessed by urinary excretion of sodium, potassium, phosphorus, urea nitrogen and creatinine, estimated from 24 h urine collections.

Symptoms (side effects), including headache, bloating, dry mouth, excessive thirst, fatigue or low energy, lightheadedness, nausea and change in taste, were collected via self-administered questionnaires (see online supplement) completed during the last 7 days of each sodium feeding period. For each symptom, potential responses were (1) ‘none’ for not experiencing any symptom, (2) ‘mild’ if symptom occurred but did not interfere with usual activities, (3) ‘moderate’ if symptom occurred and somewhat interfered with usual activities and (4) ‘severe’ if participants were unable to perform usual activities due to the symptom.

This analysis of the DASH-Sodium trial included 390 (95%) of the 412 randomised participants. Excluded participants were those with missing information on headaches in any of the three feeding periods. For the primary analysis in this study, headache was defined as ‘any headache’ (mild, moderate or severe) during the last 7 days of each feeding period. Subsequently, we report frequency of headache by severity.

The means and proportions between groups were explored using t tests and χ2 tests, respectively. A non-parametric test (extension of Wilcoxon rank-sum test) was used for trends in the frequency of headache by sodium intake. Since multiple observations were obtained on each participant, we used generalised estimating equation (GEE) models,27 with a logit link and binomial error and an exchangeable covariance structure, to model the odds of a headache. The adjusted covariates used in this analysis were measured at baseline. Models were adjusted for age, sex, race, clinical site, systolic blood pressure, BMI and smoking status. The potential for carryover effects was unavoidable in this trial; however, since the experimental agent was one's diet and participants must eat something during these intervals, statistical GEE models were also adjusted for carryover effects from the previous periods. To address the qualitative consistency and benefit-hazard profiles between participants, subgroup analysis by diet stratified by age, sex, race, obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2 vs not) and hypertension (blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg vs not) status at baseline were also performed. Interactions between subgroups were tested by the addition of an interaction term to the main effects model.

Each participant provided written, informed consent.

A p value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using Stata V.12.1 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

The 390 participants included in our analyses were those with completed symptoms questionnaires—192 (94%) of the 204 participants assigned to the control diet and 198 (95%) of the 208 participants assigned to the DASH diet. Clinical and demographic characteristics of the two groups were similar (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants in DASH-Sodium trial (number (percentage) or mean (SD))

| Characteristic | Control diet (n=192) | DASH diet (n=198) | Total (n=390) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 49 (10) | 47 (10) | 48 (10) |

| Females, n (%) | 104 (54) | 118 (60) | 222 (57) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 78 (41) | 81 (41) | 159 (41) |

| African American | 109 (57) | 114 (57) | 223 (57) |

| Other | 5 (3) | 3 (2) | 8 (2) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 30 (5) | 29 (5) | 29.2 (5) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 135 (9) | 134 (9) | 135 (9) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 86 (4) | 85 (5) | 86 (4) |

| Hypertension, n (%)* | 76 (40) | 79 (40) | 155 (40) |

| Current Smoker, n (%) | 21 (11) | 21 (11) | 42 (11) |

*Hypertension was defined as an average systolic blood pressure of 140 mm of Hg or an average diastolic blood pressure of 90 mm Hg during the three screening visits.

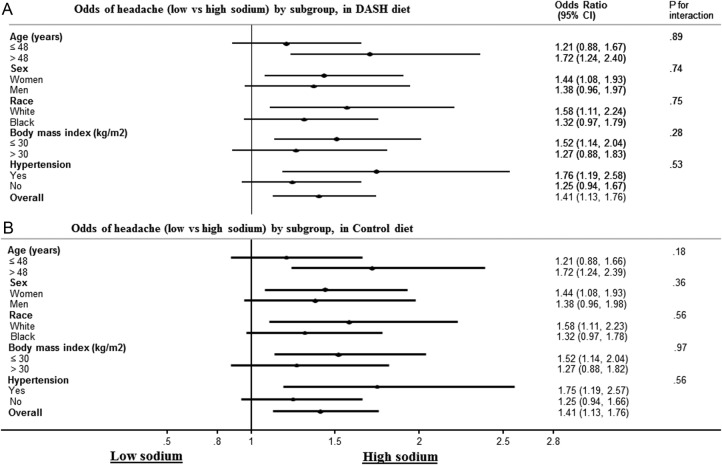

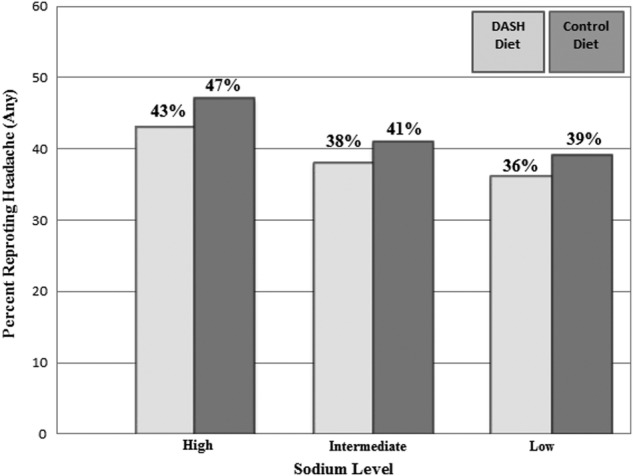

Figure 2 displays the distribution of headaches by sodium level and assigned diet. The highest occurrence of headache was reported by participants on the control diet with high sodium (47%) and the lowest by participants on the DASH diet with low sodium level (36%). On both diets, the number of headaches reported was greatest for the high sodium level and least on the low sodium level.

Figure 2 .

Frequency of headache by diet and sodium level.

Among those assigned to the control diet, mean (SD) urinary sodium excretion was 141 (55), 106 (43) and 64 (37) mmol per 24 h during the high, intermediate and low sodium feeding periods, respectively. In the DASH diet group, mean (SD) urinary sodium levels were 144 (57), 107 (52) and 67 (46) mmol per 24 h during the high, intermediate and low sodium feeding periods, respectively. On each sodium level, mean urinary sodium excretion was similar in those assigned to the two diets (each p>0.05). Mean urinary potassium and urea nitrogen were higher in the DASH diet group, reflecting the higher vegetable, dairy and protein content of the DASH diet compared with the control diet, at each sodium level (table 2).

Table 2.

Urinary excretion according to sodium level and diet (Mean (SD))

| Level of sodium |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High |

Intermediate |

Low |

||||

| DASH (n=198) | Control (n=192) | DASH (n=198) | Control (n=192) | DASH (n=198) | Control (n=192) | |

| Sodium | ||||||

| g/day | 3.3 (1.3) | 3.2 (1.3) | 2.5 (1.2) | 2.4 (0.9) | 1.5 (1.1) | 1.5 (0.8) |

| mmol/day | 144 (57) | 141 (55) | 107 (52) | 106 (43) | 67 (46) | 64 (37) |

| Potassium | ||||||

| g/day | 3.0 (1.1) | 1.6 (0.5) | 3.2 (1.2) | 1.6 (0.5) | 3.2 (1.1) | 1.6 (0.5) |

| mmol/day | 76 (27) | 40 (14) | 82 (31) | 41 (14) | 81 (29) | 41 (14) |

| Urea nitrogen g/day |

11.5 (4) | 9.5 (3.2) | 12.4 (4.5) | 9.7 (3.4) | 12 (4) | 10 (3.3) |

| Creatinine g/day |

1.4 (0.5) | 1.5 (0.5) | 1.5 (0.6) | 1.5 (0.6) | 1.4 (0.5) | 1.5 (0.6) |

Table 3 shows differences in the odds of headache by diet and sodium level. Compared with the high sodium level, we observed a lower odds of any headache during the low sodium period both on the control diet (adjusted OR=0.69, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.99) and the DASH diet (adjusted OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.98). Although the relationship appeared graded (figure 2), there was no significant difference between the intermediate level of sodium and either the low or high sodium levels, on either diet. There was no significant association of diet pattern (DASH vs control) with headache on any sodium level. There was also no significant interaction between diet and sodium on the occurrence of headaches (p interaction >0.05). Compared with the control diet with high sodium, there was a reduced risk of a headache on the DASH diet with low sodium (adjusted OR=0.64, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.99, p=0.05).

Table 3.

OR of headaches by diet and sodium sequence

| OR (95%CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium effects on the DASH diet | ||

| Intermediate vs high sodium | 0.72 (0.51 to 1.01) | 0.06 |

| Low vs intermediate sodium | 0.96 (0.68 to 1.37) | 0.85 |

| Low vs high sodium | 0.69 (0.49 to 0.98) | 0.04 |

| Sodium effects on the control diet | ||

| Intermediate vs high sodium | 0.81 (0.57 to 1.15) | 0.24 |

| Low vs intermediate sodium | 0.86 (0.59 to 1.24) | 0.42 |

| Low vs high sodium | 0.69 (0.49 to 0.99) | 0.05 |

| Diet effects (DASH vs control) at each sodium level | ||

| On high sodium | 0.65 (0.37 to 1.12) | 0.12 |

| On intermediate sodium | 0.57 (0.29 to 1.12) | 0.10 |

| On low sodium | 0.64 (0.36 to 1.13) | 0.12 |

| Low sodium on DASH vs high sodium on control | 0.64 (0.14 to 0.99) | 0.05 |

Models adjusted for age, sex, race, site, systolic blood pressure, body mass index, smoking status and carryover effects from the previous period.

While on control diet, the number of persons who reported a severe headache was 4 (2.1%) during high, 1 (0.5%) during intermediate and 1 (0.5%) during low sodium periods, respectively (p for trend =0.13). On DASH diet, the corresponding number of persons who reported a severe headache was 8 (4%) during high, 2 (1%) during intermediate and 3 (1.5%) during low sodium periods, respectively (p for trend=0.08). The frequency of severe headache was similar (p=0.3) by diet (DASH 8 (4%) and control 4 (2%)) during high sodium feeding period (table 4).

Table 4.

Occurrence and severity of headache by sodium level and diet, n (%)

| Level of sodium |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High |

Intermediate |

Low |

||||

| DASH (n=198) | Control (n=192) | DASH (n=198) | Control (n=192) | DASH (n=198) | Control (n=192) | |

| Mild | 60 (30) | 70 (36) | 43 (22) | 62 (32) | 53 (27) | 53 (28) |

| Moderate | 17 (9) | 17 (9) | 31 (16) | 16 (8) | 16 (8) | 21 (11) |

| Severe | 8 (4) | 4 (2) | 2 (1) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1) | 1 (0.5) |

There was no evidence that the relationship between sodium levels and headache was modified by age, sex, race, baseline BMI or blood pressure (figure 3).

Figure 3 .

(A) Odds of headache (low vs high sodium) by subgroup, in the DASH diet. (B) Odds of headache (low vs high sodium) by subgroup, in the control diet.

Discussion

In this secondary analysis of the DASH-Sodium trial, which enrolled adults with prehypertension and stage 1 hypertension, a reduced dietary sodium intake was associated with a lower risk of headache, both on the control diet and the DASH diet. In contrast, the risk of headache was similar on the DASH and control diets.

The epidemiological literature on headaches in adults is limited.1 2 6 However, it is well recognised that, compared to normotensive individuals, individuals with hypertension have a higher frequency of headaches.16–19 28 Of note, Cooper et al17 reported a direct relationship of headaches with both systolic and diastolic blood pressure. As regards trials, in a pooled analysis that included seven double-blinded, randomised placebo controlled trials of Irbesartan therapy, Hansson et al29 found a direct relationship of diastolic blood pressure with incident headaches in 2673 patients with mild-to-moderate hypertension.

The association between dietary sodium intake and blood pressure is also well recognised.30 31 The DASH diet alone and in combination with reduced sodium intake lowers blood pressure in patients with or without hypertension.20 21 It is noteworthy that there was no significant relationship between diet pattern and headache. This suggests that a process that is independent of a blood pressure may mediate the relationship between sodium and headaches.

Our results contrast with the popular belief that a diet rich in fruits, vegetables and potassium and low in saturated and total fat may ease the frequency, or even prevent, headache.32 Several dietary factors, including fasting, alcoholic drinks, chocolate, coffee and cheese, appear to trigger vascular headache (cluster or migraine) in adults.33–36 In some studies, an increased intake of monosodium glutamate is associated with the occurrence of headaches.22–24 However, a recent review concluded that evidence on the relationship of sodium glutamate intake and headaches is inconsistent.37 In one study of 200 adults (mean age 37.7 years, 81% females), monosodium glutamate was identified as a trigger for migraine headache in only 5 (2.5%) of study participants.36 However, data on the relationship between sodium intake and any form of headaches are sparse.

The results of this study provide encouraging evidence in support of dietary recommendations to lower sodium intake: recommendations which are currently based on the relationship of sodium intake with blood pressure. The daily intake of sodium in adults living in the USA is already in excess of their physiological need and for many individuals, is much higher than the highest level tested in this study.38 39 Our results also support the recent WHO guidelines for reducing sodium intake to less than 87 mmol/day40 and American Heart Association guidelines for reducing sodium intake to 65 mmol/day.31

Strengths of our study include its randomised controlled design comparing two diets using a parallel design and a three-period crossover of three levels of dietary sodium (high, intermediate and low). Dietary intake during the feeding periods was closely monitored and vigorous efforts were made to promote adherence with assigned diets. The participants of this study were healthy, non-institutionalised, racially diverse, middle-aged and older-aged men and women. Hence we believe that these results are applicable to a large fraction of adults.

Our study also has limitations. Information on the prevalence of headache at baseline from eligible participants was lacking. In addition, there was no information about the type of headache (tension, cluster or migraine) experienced by study participants. However, we suspect that most of the headaches were tension headaches. Whether a reduced sodium intake can prevent vascular headache is unknown. Second, the instrument was administered just once in each feeding period and does not allow calculation of an event rate, such as person-days of headaches. Third, these are secondary, post hoc analyses from a trial that was not explicitly designed to test the effects of dietary factors on headaches. Nonetheless, a rigorously controlled feeding study designed to test the effects of dietary factors on occurrence of headaches would be extremely expensive and logistically challenging. Fourth, our results likely underestimate the relationship of sodium intake with headaches. The range of sodium intake was relatively narrow—the highest sodium group in our trial actually corresponds to the average in the USA and is much lower than the intake in many countries, particularly in Asia. Self-report of symptoms is inherently imprecise and could bias results to the null, given that a validated instrument was not used for patient-reported headache.

In conclusion, a reduced sodium intake was associated with significantly lower risk of headache, while diet patterns had no effect on the risk of headaches. A reduced dietary sodium intake offers a novel approach to prevent headache in adults. Additional studies are needed to replicate these findings and to explore mechanisms that mediate the association between sodium intake and headache.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All three authors (MA, MW and LJA) have substantially contributed to the conception, drafting, editing and revising for the important intellectual content of the manuscript. MA and MW were responsible for analyses of the data. All three authors participated in the interpretation of the analysis and agreed for the final approval of the version to be published. Authors are in agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work related to this manuscript and responsible for the integrity of any part of the work shown in this post hoc analysis of the DASH-Sodium clinical trial.

Funding: LJA and MW were co-investigators in a trial sponsored by the McCormick Science Institute (completed in spring 2013).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Institutional review boards at the participating centres and an external data and safety monitoring committee approved the trial protocol and consent procedures.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Benbir G, Karadeniz D, Göksan B. The characteristics and subtypes of headache in relation to age and gender in a rural community in Eastern Turkey. Agri 2012;24:145–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stovner Lj, Hagen K, Jensen R et al. The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia 2007;27:193–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andlin-Sobocki P, Jönsson B, Wittchen HU et al. Cost of disorders of the brain in Europe. Eur J Neurol 2005;12(Suppl 1):1–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jensen R, Stovner LJ. Epidemiology and comorbidity of headache. Lancet Neurol 2008;7:354–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zwart JA, Dyb G, Holmen TL et al. The prevalence of migraine and tension-type headaches among adolescents in Norway: The Nord- Trøndelag Health Study (Head-Hunt). Cephalalgia 2004;24:373–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rasmussen BK. Epidemiology of headache. Cephalalgia 2001;21:774–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berg J, Stovner LJ. Cost of migraine and other headaches in Europe. Eur J Neurol 2005;12(Suppl 1):59–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rasmussen BK, Jensen R, Olesen J. Impact of headache on sickness absence and utilisation of medical services: a Danish population study. J Epidemiol Community Health 1992;46:443–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lyngberg AC, Rasmussen BK, Jensen R et al. Secular changes in health care utilization and work absence for migraine and tension type headache. A population based study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2005;20:1007–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Von Korff M, Stewart W, Lipton RB. Assessing headache severity: new directions. Neurology 1998;44(Suppl 4):40–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michel P, Dartiques J, Duru G et al. Incremental absenteeism due to headache in migraine: results from the Mig-Access French National Cohort. Cephalalgia 1999;19:503–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vinding GR, Zeeberg P, Lyngberg A et al. The burden of headache in a patient population from a specialized headache centre. Cephalalgia 2007;27:263–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medizabel JE, Rothrock JF. An interregional comparative study of headache clinic populations. Cephalalgia 1998;18:57–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saper JR, Lake AE, Madden SF et al. Comprehensive/tertiary care for headache: a 6-month outcome study. Headache 1999;39:249–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bussone G, Usai S, Grazzi L et al. Disability and quality of life in different primary headaches: results from Italian studies. Neurol Sci 2004;25(Suppl 3):S105–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kruszewski P, Bieniaszewski L, Neubauer J et al. Headache in patients with mild to moderate hypertension is generally not associated with simultaneous blood pressure elevation. J Hypertens 2000;18:437–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper WD, Glover DR, Hormbrey JM et al. Headache and blood pressure: evidence of a close relationship. J Hum Hypertens 1989;3:41–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janeway TC. A clinical study of hypertensive cardiovascular disease. Arch Intern Med 1913;12:755–98. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barlow DH, Beevers DG, Hawthorne VM et al. Blood pressure measurement at screening and in general practice. Br Heart J 1977;39:7–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E et al. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. DASH Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med 1997;336:1117–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sacks FM, Svetkey LP, Vollmer WM et al. ; DASH-Sodium Collaborative Research Group. Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. DASH-Sodium Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med 2001;344:3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang WH, Drouin MA, Herbert M et al. The monosodium glutamate symptom complex: assessment in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1997;99(6 Pt 1):757–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Randolph TG, Rollins JP. Beet sensitivity: allergic reactions from the ingestion of beet sugar (sucrose) and monosodium glutamate of beet origin. J Lab Clin Med 1950;36:407–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ratner D, Eshel E, Shoshani E. Adverse effects of monosodium glutamate: a diagnostic problem. Israel J Med Sci 1984;20:252–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Svetkey LP, Sacks FM, Obarzanek E et al. The DASH Diet, Sodium Intake and Blood Pressure Trial (DASH-sodium): rationale and design. DASH-Sodium Collaborative Research Group. J Am Diet Assoc 1999;99(8 Suppl):S96–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.[No authors listed]. The sixth report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Arch Intern Med 1997;157:2413–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sigurdsson JA, Bengtsson C. Symptoms and signs in relation to blood pressure and antihypertensive treatment. A cross-sectional and longitudinal population study of middle-aged Swedish women. Acta Med Scand 1983;213:183–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hansson L, Smith DH, Reeves R et al. Headache in mild-to-moderate hypertension and its reduction by irbesartan therapy. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:1654–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aburto NJ, Ziolkovska A, Hooper L et al. Effect of lower sodium intake on health: systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ 2013;346:f1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Appel LJ, Brands MW, Daniels SR et al. American Heart Association. Dietary approaches to prevent and treat hypertension: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension 2006;47:296–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buchholz D. Heal your headache: the 1-2-3 program for taking charge of your headaches. New York: Workman, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Savi L, Rainero I, Valfrè W et al. Food and headache attacks. A comparison of patients with migraine and tension-type headache. Panminerva Med 2002;44:27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peatfield RC. Relationships between food, wine, and beer-precipitated migrainous headaches. Headache 1995;35:355–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carod-Artal FJ, Ezpeleta D, Martín-Barriga ML et al. Triggers, symptoms, and treatment in two populations of migraneurs in Brazil and Spain. A cross-cultural study. J Neurol Sci 2011;304:25–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fukui PT, Gonçalves TR, Strabelli CG et al. Trigger factors in migraine patients. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2008;66(3A):494–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Freeman M. Reconsidering the effects of monosodium glutamate: a literature review. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2006;18:482–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown IJ, Tzoulaki I, Candeias V et al. Salt intakes around the world: implications for public health. Int J Epidemiol 2009;38:791–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention Fact sheet; http://www.cdc.gov/salt/pdfs/Sodium_Fact_Sheet.pdf (accessed 28 Sep 2013).

- 40.WHO. Guideline: sodium intake for adults and children. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO), 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.