Abstract

During recent decades, the increasing use of opioids for chronic non-cancer pain has raised concerns regarding tolerance, addiction, and importantly cognitive dysfunction. Current research suggests that the somatotrophic axis could play an important role in cognitive function. Administration of growth hormone (GH) to GH-deficient humans and experimental animals has been shown to result in significant improvements in cognitive capacity. In this report, a patient with cognitive disabilities resulting from chronic treatment with opioids for neuropathic pain received recombinant human growth hormone (rhGH) replacement therapy. A 61-year-old man presented with severe cognitive dysfunction after long-term methadone treatment for intercostal neuralgia and was diagnosed with GH insufficiency by GH releasing hormone-arginine testing. The effect of rhGH replacement therapy on his cognitive capacity and quality of life was investigated. The hippocampal volume was measured using magnetic resonance imaging, and the ratios of the major metabolites were calculated using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Cognitive testing revealed significant improvements in visuospatial cognitive function after rhGH. The hippocampal volume remained unchanged. In the right hippocampus, the N-acetylaspartate/creatine ratio (reflecting nerve cell function) was initially low but increased significantly during rhGH treatment, as did subjective cognitive, physical and emotional functioning. This case report indicates that rhGH replacement therapy could improve cognitive behaviour and well-being, as well as hippocampal metabolism and functioning in opioid-treated patients with chronic pain. The idea that GH could affect brain function and repair disabilities induced by long-term exposure to opioid analgesia is supported.

Previous research has suggested that growth hormone (GH) and its mediator insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) could affect brain targets for these hormones and influence cognitive functioning in humans1 and rats.2 This is supported by findings indicating that both GH and IGF-1 receptors are located in several brain regions, including the hippocampus, a brain area known to have an essential role in cognitive processes, particularly memory and learning. The exact mechanism by which the GH/IGF-1 axis affects cognitive functioning has not yet been fully clarified, and very little is known about the cognitive capacity of adults with either childhood-onset or adult-onset GH deficiency (GHD). Nonetheless, accumulating data suggest that the cognitive abilities, especially attention and memory, of adult patients with GHD could be impaired.3,4 There is also evidence that impaired cognitive functioning could be induced by addictive drugs, such as central stimulants and opioids.5 In fact, cognitive dysfunction has been recorded in patients receiving long-term opioid treatment for chronic non-cancer pain.6,7 These effects of opioids on cognition appear to result from inhibition of neurogenesis8 and increased apoptosis induced by these drugs.9,10 Moreover, we have previously reported that recombinant human growth hormone (rhGH) reversed morphine-induced apoptosis in primary cell cultures from the murine foetal hippocampus.11 Furthermore, GH treatment of hypophysectomised male rats improved their performance in various memory tests.12 Several studies involving patients with GHD have demonstrated beneficial effects on cognitive capacity following GH replacement therapy.13,14 These observations prompted us to study the effects of GH replacement therapy on cognitive disabilities in patients chronically exposed to opioids.

The aim of the study was to examine the effect of daily administration of rhGH to a patient with chronic pain and impaired cognitive functioning as a possible complication of long-term exposure to methadone, using hormonal analysis, and neuropsychological and neuroradiological tests.

Case report

A 61-year-old man with chronic, severe, left-sided, intercostal neuropathic pain after a kidney operation had been receiving 90–110 mg of methadone daily for 6 years and was diagnosed with adult-acquired GHD. His symptoms were somnolence, fatigue, sweating, and concentration and memory disturbances, including depressive mood. He had difficulty finding his way home from the central part of the city. He had no other significant comorbidities or medications during the study period.

Four healthy volunteers were used to estimate the reproducibility of the hippocampal volume measurements on magnetic resonance (MR) images and of the metabolite ratios of the hippocampal region on MR spectroscopy. They underwent the MR examinations twice, with a 0.5- to 4.5-month interval.

Hormonal analysis

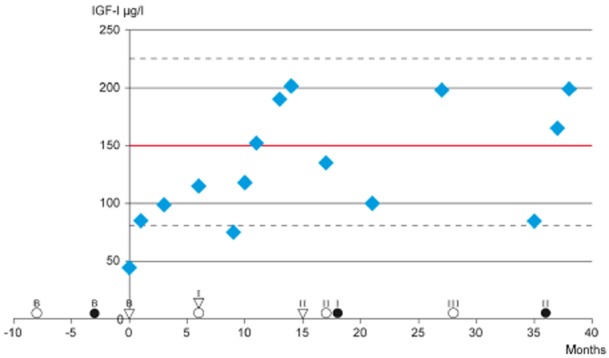

A GH releasing hormone (GHRH)-arginine test was performed to assess GH insufficiency. IGF-1 and B-glucose were monitored every 1–3 months to guide the dose of rhGH (Fig. 1). The thyroid, gonadal and adrenal hormonal axes were also monitored at baseline, and at the end of 6 months of effective treatment period.

Fig 1.

Time schedule of the examinations and the patient' h rhGH.  Cognitive testing; • MR examination; ▽ Quality of life and symptom evaluation with EORTC-QLQ; ----- Upper and lower limits of the normal range (2 SD variation); ____ Statistical mean of the normal range. Low dose 0,1–0,2 mg rhGH sc daily; effective dose 0,3 mg rhGH sc daily. IGF-1, insulin growth-like factor-1; rhGH, recombinant human growth hormone; MR, magnetic resonance; EORTC-QLQ, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality-of-Life Questionnaire; SD, standard deviation.

Cognitive testing; • MR examination; ▽ Quality of life and symptom evaluation with EORTC-QLQ; ----- Upper and lower limits of the normal range (2 SD variation); ____ Statistical mean of the normal range. Low dose 0,1–0,2 mg rhGH sc daily; effective dose 0,3 mg rhGH sc daily. IGF-1, insulin growth-like factor-1; rhGH, recombinant human growth hormone; MR, magnetic resonance; EORTC-QLQ, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality-of-Life Questionnaire; SD, standard deviation.

rhGH treatment

The patient received a daily low dose (0.1–0.2 mg) of rhGH (Genotropin®, Pfizer Health AB, Strängnäs, Sweden) for the first 6 months to keep the IGF-1 levels below or in the lower quartile of the normal range (= age-corrected mean ± 2 standard deviation; Fig. 1). Thereafter, the rhGH dose was increased to 0.3 mg to keep the IGF-1 levels above the mean but within the normal range (i.e. effective treatment) as suggested by Bennett15 and Ahmad et al.16

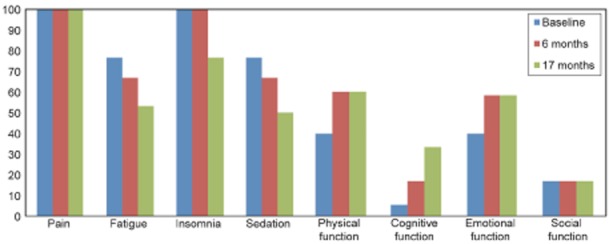

Measurement of symptoms and quality of life

The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality-of-Life Questionnaire (EORTC-QLQ)17 form, which measures symptoms of pain, fatigue, insomnia, sedation, and physical, social, emotional and cognitive functioning, was used at baseline, and again after 6 and 15 months of treatment.

Assessment of cognitive capacity

Cognitive skills were tested using the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS III), the Claeson–Dahl verbal learning and verbal retention tests, and the Rey Complex Fig. Test for visuospatial retention at baseline, after 6 months of low-dose treatment and 6 months of effective treatment, and after a total of 28 months of treatment (Fig. 1).

MR examinations

MR examinations were performed with an MR imager operating at 1.5 T.

T1- and T2-weighted sequences were used for imaging the hippocampi. Hippocampal volumes were measured manually in coronal slices perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the hippocampus by one observer. All volume measurements were repeated once for each examination and the mean value was used.

Proton MR spectroscopy of the hippocampal region was performed using a single voxel technique including almost the entire hippocampus. A PRESS sequence with a TR/TE 2500/22 ms was used and the LCModel was used for analysis. The metabolites were quantified as ratios to creatine (Cr) to avoid the effects of cerebrospinal fluid in the voxels. The ratios used were N-acetylaspartate (NAA)/Cr, choline (Cho)/Cr, and myoinositol (Ins)/Cr.

MR examinations were made at baseline and at 18 and 36 months after initiation of rhGH treatment (Fig. 1).

The metabolite changes were considered significant if they were at least 1.5 times larger than the largest percentage change in the controls.

The study was accepted by the Uppsala University Ethics Committee 2006 02 08 Dnr 2006:015 (Regionala Etikprövningsnämnden, Box 256, 751 22 Uppsala Sweden).

Results

Hormonal analysis

At baseline, GHRH-arginine testing of the patient revealed a GHD with maximum GH levels of 4.3 μg/l and an IGF-1 level of 44 μg/l (normal range 81–225 μg/l). His body mass index (BMI) was 25.6, which satisfies the BMI corrected definition of GHD (cut-off level for GH level is below 8.0 μg/l for BMI > 25).18 After initiation of rhGH therapy, IGF-1 levels increased slowly. In the first 6 months, with low-dose treatment, IGF-1 levels remained in the lower quartile of the normal range (Fig. 1). After increasing the dose of rhGH, the patient's IGF-1 level initially reached the mean 150 μg/l of the normal range (Fig. 1).

Thyroid, adrenal and gonadal axes, including prolactin, remained unchanged during the treatment period. All the measurements were within normal limits except for testosterone index, which was low at 17–18% but also unchanged through the treatment period. (The patient had earlier been offered but declined testosterone substitution.)

Cognitive capacity and quality of life

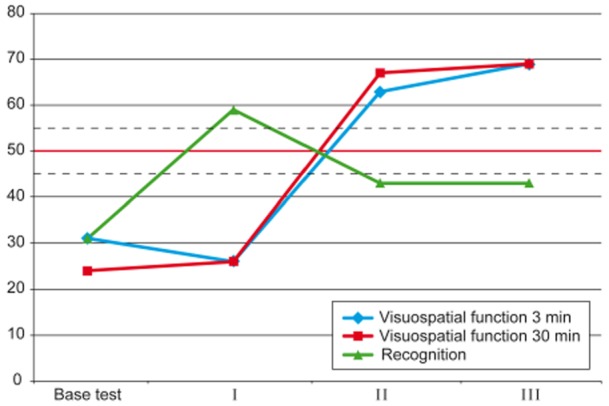

The Rey Complex Fig. cognitive test scores indicated an increase in visuospatial performance (Fig. 2) after 6 months of effective (high-dose) rhGH treatment in parallel with an increase in the levels of IGF-1 above the mean of the normal range. This is in contrast to the 6 months of low-dose treatment, during which there were no changes in this test. There were no changes in the verbal learning and retention test scores. There was successive improvement in symptoms of fatigue, insomnia, sedation, and cognitive, emotional and physical functioning (EORTC-QLQ scores). However, the intensity of pain was unchanged (Fig. 3).

Fig 2.

Cognitive tests. Reyes Complex Fig. Test scores at baseline (base test), after 6 months of low-dose treatment (I) and after 6 months of effective rhGH treatment resulting in IGF-1 levels above the normal mean (II). ------ Normal range of variation;  Statistical mean of the normal range. rhGH, recombinant human growth hormone; IGF-1, insulin growth-like factor-1.

Statistical mean of the normal range. rhGH, recombinant human growth hormone; IGF-1, insulin growth-like factor-1.

Fig 3.

Quality of life and symptoms tested with the EORTC-QLQ form. For symptoms, a low value equates to a low intensity; for function, a low value equates to a low level of functioning. EORTC-QLQ, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality-of-Life Questionnaire.

MR evaluation of the hippocampi

The hippocampi of the patient were normal in size. However, both of the patient's hippocampi were the same size, or the left was a little smaller; usually the right hippocampus is a little larger. The changes in the patient's hippocampal volumes during follow-up did not exceed the differences between repeat studies in the controls (Table 1).

Table 1.

Metabolite measurements; percentage change in the follow-up examinations compared with the baseline examination

| Right hippocampal region | Left hippocampal region | Estimated significant change* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up I | Follow-up II | Follow-up I | Follow-up II | ||

| Choline/creatine | +46% | +12% | −8% | −13% | ± 20% |

| NAA/creatine | +43% | −3% | −8% | −21% | ± 30% |

| Myoinositol/creatine | +10% | −1% | −5% | −13% | ± 30% |

Bold numbers indicate significant changes.

Based on the variations in the repeated examinations of the healthy controls.

NAA, N-acetyl aspartate.

Before treatment, the NAA/Cr ratio in the right hippocampus of the patient was lower than that in the controls: 0.79 vs. 1.18 (= mean, range 1.11–1.38) (Tables 2 and 3). After treatment with rhGH, the NAA/Cr and Cho/Cr ratios increased significantly in the right hippocampus: NAA/Cr increased by 43% and Cho/Cr by 46%. The estimated limits of significant, i.e. not method-related, changes were ± 35% and ± 25%, respectively. In the last examination, performed when the IGF-1 concentration was temporarily low, the metabolite ratios did not differ significantly from baseline. The metabolite ratios did not change significantly in the left hippocampus throughout the study.

Table 2.

Variation of metabolite ratios in repeated examinations of the controls

| Metabolite ratio | Change in repeated examinations (%) | Change estimated not to be method-related (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right | Left | Control 1 | Control 2 | Control 3 | Control 4 | ||||||

| Mean ± SD, range | Mean ± SD, range | Right | Left | Right | Left | Right | Left | Right | Left | ||

| Cho/Cr | 0.31 ± 0.03, 0.28–0.33 | 0.33 ± 0.02, 0.32–0.35 | +17 | +13 | −7 | +13 | +9 | +11 | −4 | +4 | ± 25 |

| NAA/Cr | 1.18 ± 0.08, 1.11–1.29 | 1.30 ± 0.08 1.22–1.38 | +21 | −24 | −7 | −8 | +5 | +11 | +8 | +15 | ± 35 |

| Ins/Cr | 0.91 ± 0.06, 0.85–0.99 | 0.98 ± 0.07 0.93–1.06 | +4 | −9 | −22 | +12 | +0.3 | + 3 | +0.7 | +13 | ± 30 |

Ratios in the second examinations are compared with those in the first examination.

Cho, choline; Cr, creatine; NAA, N-acetyl aspartate; Ins, myoinositol; SD, standard deviation.

Table 3.

Changes of the metabolite ratios in the follow-up examinations of the patient compared with his baseline examination

| Metabolite ratio | Right hippocampal region | Left hippocampal region | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio in change (%) | Ration in change (%) | |||||

| Exam. I | Follow-up I | Follow-up II | Exam. I | Follow-up I | Follow-up II | |

| Cho/Cr | 0.30 | +46% | +12% | 0.40 | −8 % | −13% |

| NAA /Cr | 0.79 | +43% | −3% | 1.31 | −8 % | −21% |

| Ins/Cr | 0.91 | +10 % | −1 | 1.09 | −5 % | −13% |

Changes larger than method-related in bold type. Abbreviations as in Table 2.

Discussion

In this report, we have described the response to rhGH replacement therapy in a patient with chronic pain and cognitive disabilities likely to be caused by long-term treatment with opioids (in this case methadone). The patient's symptoms of fatigue, sedation and insomnia improved, along with subjective cognitive, physical and emotional functioning, despite a lack of improvement in the intensity of the pain. The Rey Complex Fig. Test indicated improvements in visuospatial functioning following 6 months of effective rhGH treatment.

The metabolite NAA is only found in nerve cells and is regarded as a marker for neuronal function. Increases in the NAA/Cr ratio indicate activated neuronal function. Choline is a marker for membrane turnover. Increase in the Cho/Cr ratio after rhGH treatment could reflect cellular proliferation. However, we did not find an increase in hippocampal volume. Data recorded by MR spectroscopy support the observations made in the neurocognitive tests: NAA and Cho levels became higher in the right hippocampus, and the cognitive improvement in visuospatial performance was attributed to the right hippocampus. The right hippocampus is associated with visual memory.19 It was intriguing to observe the changes in the specific visuospatial deficit in this patient, who was so compromised in cognitive capacity at baseline that he could not find his way home. After 6 months of effective treatment with rhGH, both his subjective cognitive functioning and the Rey Complex Fig. Test score revealed improvement congruent with increased functioning of the right hippocampus. The metabolite concentrations measured by proton MR spectroscopy decreased during extended follow-up after the IGF-1 concentration had dropped. The reason for this drop in IGF-1 is unknown, since the dose of rhGH remained the same. Nonetheless, the IGF-1 values remained within the normal range.

The finding that, at baseline, only the right hippocampus was affected remains to be explained. If the opioid treatment alone had caused the change, a bilateral, symmetrical change seems more likely. The chronic pain stimuli, which in this case had a strictly unilateral location in the left thorax, might have been a contributing factor, but knowledge on the somatosensory projections to the hippocampus, and the possible somatotopic organisation, is scarce. There is evidence that stress and pain could affect the functioning and volume of the hippocampus.20,21 In our study, only the affected hippocampus responded to treatment. A decrease in hippocampal volume has been detected in patients suffering from chronic pain due to fibromyalgia,22 as well as in complex regional pain syndrome and low back pain.23 In our patient, the hippocampi were not shrunken, but the normal volume difference between the right and left sides was lacking.

Although opioids provide effective pain control, they are connected with some unwanted events, such as constipation, nausea and vomiting, along with adverse effects associated with cognition and memory function. Opioids like morphine and oxycodone may impair cognitive capacity in a dose-dependent manner.24,25 Cognitive impairment in drug-dependent patients receiving methadone maintenance treatment has also been reported,26 although the literature is limited and results remain controversial. For example, heroin addicts on long-term methadone treatment did not deteriorate in cognition or memory in one study.27 Data from animal studies suggest that neural apoptotic damage could contribute to impairment of the cognitive abilities of mice after chronic methadone administration and withdrawal.28

Our findings, although they were only from a pilot study of a single patient, are in line with previous observations that opioid-induced cell damage caused by increased apoptosis11 and inhibited neurogenesis8 can be reversed by growth factors such as rhGH,11 and that GH/IGF-1 contribute to plastic regeneration and neuroprotection.5,29 To confirm and better understand the mechanisms behind these preliminary observations, we are now planning another study with more subjects. The aim is to continue and extend our studies of patients with chronic pain who have received long-term opioids and who subsequently receive rhGH replacement therapy. Our long-term aim is to describe the relevant strategies associated with the ability of rhGH to reverse opioid-induced damage of hippocampal cells and repair other brain damage caused by misuse of other drugs of abuse, including alcohol, central stimulants and anabolic steroids.

In conclusion, the cognitive capacity of a patient with impairment of several aspects of cognitive functioning, presumably as a result of side effects of long-term treatment with strong opioids, improved significantly following treatment with rhGH. The improvements in neuropsychological tests were correlated with higher plasma levels of IGF-1, as well as neuroradiological evidence of increased hippocampal activation.

Conflict of interest: The authors have nothing to declare.

Funding: This study was supported by the Swedish Medical Research Council (Grant 9459), the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research, and grants from the Uppsala Berzelii Technology Centre for Neurodiagnostics.

References

- 1.Nyberg F. Growth hormone in the brain: characteristics of specific brain targets for the hormone and their functional significance. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2000;21:330–348. doi: 10.1006/frne.2000.0200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Le Greves M, Steensland P, Le Greves P, Nyberg F. Growth hormone induces age-dependent alteration in the expression of hippocampal growth hormone receptor and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits gene transcripts in male rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:7119–7123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092135399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Dam PS, Aleman A. Insulin-like growth factor-I, cognition and brain aging. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;490:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deijen JB, de Boer H, Blok GJ, van der Veen EA. Cognitive impairments and mood disturbances in growth hormone deficient men. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1996;21:313–322. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(95)00050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nyberg F. The role of the somatotrophic axis in neuroprotection and neuroregeneration of the addictive brain. Int Rev Neurobiol. 88:399–427. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(09)88014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sjogren P, Christrup LL, Petersen MA, Hojsted J. Neuropsychological assessment of chronic non-malignant pain patients treated in a multidisciplinary pain centre. Eur J Pain. 2005;9:453–462. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaertner J, Radbruch L, Giesecke T, Gebershagen H, Petzke F, Ostgathe C, Elsner F, Sabatowski R. Assessing cognition and psychomotor function under long-term treatment with controlled release oxycodone in non-cancer pain patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2006;50:664–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.01027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eisch AJ, Barrot M, Schad CA, Self DW, Nestler EJ. Opiates inhibit neurogenesis in the adult rat hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:7579–7584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120552597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu S, Sheng WS, Lokensgard JR, Peterson PK. Morphine induces apoptosis of human microglia and neurons. Neuropharmacology. 2002;42:829–836. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mao J, Sung B, Ji RR, Lim G. Neuronal apoptosis associated with morphine tolerance: evidence for an opioid-induced neurotoxic mechanism. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7650–7661. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-17-07650.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Svensson AL, Bucht N, Hallberg M, Nyberg F. Reversal of opiate-induced apoptosis by human recombinant growth hormone in murine foetus primary hippocampal neuronal cell cultures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7304–7308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802531105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Le Greves M, Zhou Q, Berg M, Les Greves P, Fholenhag K, Meyerson B, Nyberg F. Growth hormone replacement in hypophysectomized rats affects spatial performance and hippocampal levels of NMDA receptor subunit and PSD-95 gene transcript levels. Exp Brain Res. 2006;173:267–273. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0438-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oertel H, Schneider HJ, Stalla GK, Holsboer F, Zihl J. The effect of growth hormone substitution on cognitive performance in adult patients with hypopituitarism. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:839–850. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(03)00151-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arwert LI, Deijen JB, Muller M, Drent ML. Long-term growth hormone treatment preserves GH-induced memory and mood improvements: a 10-year follow-up study in GH-deficient adult men. Horm Behav. 2005;47:343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bennett R. Growth hormone in musculoskeletal pain states. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2004;6:266–273. doi: 10.1007/s11926-004-0034-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmad AM, Hopkins MT, Thomas J, Ibrahim H, Fraser WD, Vora JP. Body composition and quality of life in adults with growth hormone deficiency; effects of low-dose growth hormone replacement. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2001;54:709–717. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2001.01275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Bjordal K, Kaasa S. Health-related quality of life in the general Norwegian population assessed by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality-of-Life Questionnaire: the QLQ = C30 (+ 3) J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1188–1196. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.3.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corneli G, Di Somma C, Baldelli R, Rovere S, Gasco V, Croce CG, Grottoli S, Maccario M, Colao A, Lombardi G, Ghigo E, Camanni F, Aimaretti G. The cut-off limits of the GH response to GH-releasing hormone-arginine test related to body mass index. Eur J Endocrinol. 2005;153:257–264. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.01967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gleissner U, Helmstaedter C, Elger CE. Right hippocampal contribution to visual memory: a presurgical and postsurgical study in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65:665–669. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.65.5.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graybiel AM, Morris R. Behavioural and cognitive neuroscience. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2011;21:365–367. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moriarty O, McGuire BE, Finn DP. The effect of pain on cognitive function: a review of clinical and preclinical research. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;93:385–404. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lutz J, Jager L, de Quervain D, Krauseneck T, Padberg F, Wichnalek M, Beyer A, Stahl R, Zirngibi B, Morhard D, Reiser M, Schelling G. White and gray matter abnormalities in the brain of patients with fibromyalgia: a diffusion-tensor and volumetric imaging study. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3960–3969. doi: 10.1002/art.24070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mutso AA, Radzicki D, Baliki MN, Huang M, Banisadr G, Centeno MV, Radulovic J, Martina M, Miller RJ, Apkarian AV. Abnormalities in hippocampal functioning with persistent pain. J Neurosci. 2012;32:5747–5756. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0587-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kerr B, Hill H, Coda B, Calogero M, Chapman CR, Hunt E, Buffington V, Mackie A. Concentration-related effects of morphine on cognition and motor control in human subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1991;5:157–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zacny JP, Gutierrez S. Characterizing the subjective, psychomotor, and physiological effects of oral oxycodone in non-drug-abusing volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;170:242–254. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1540-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rapeli P, Fabritius C, Alho H, Salaspuro M, Wahlbeck K, Kalska H. Methadone vs. buprenorphine/naloxone during early opioid substitution treatment: a naturalistic comparison of cognitive performance relative to healthy controls. BMC Clin Pharmacol. 2007;7:5. doi: 10.1186/1472-6904-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soyka M, Zingg C, Koller G, Hennig-Fast K. Cognitive function in short- and long-term substitution treatment: are there differences? World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010;11:400–408. doi: 10.1080/15622970902995604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tramullas M, Martinez-Cue C, Hurle MA. Chronic methadone treatment and repeated withdrawal impair cognition and increase the expression of apoptosis-related proteins in mouse brain. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;193:107–120. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0751-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Isgaard J, Aberg D, Nilsson M. Protective and regenerative effects of the GH/IGF-I axis on the brain. Minerva Endocrinol. 2007;32:103–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]