Synopsis

Objective

The maintenance of youthful skin appearance is strongly desired by a large proportion of the world's population. The aim of the present study was therefore to evaluate the effect on skin wrinkling, of a combination of ingredients reported to influence key factors involved in skin ageing, namely inflammation, collagen synthesis and oxidative/UV stress. A supplemented drink was developed containing soy isoflavones, lycopene, vitamin C and vitamin E and given to post-menopausal women with a capsule containing fish oil.

Method

We have performed a double-blind randomized controlled human clinical study to assess whether this cocktail of dietary ingredients can significantly improve the appearance of facial wrinkles.

Results

We have shown that this unique combination of micronutrients can significantly reduce the depth of facial wrinkles and that this improvement is associated with increased deposition of new collagen fibres in the dermis.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that consumption of a mixture of soy isoflavones, lycopene, vitamin C, vitamin E and fish oil is able to induce a clinically measureable improvement in the depth of facial wrinkles following long-term use. We have also shown, for the first time with an oral product, that the improvement is associated with increased deposition of new collagen fibres in the dermis.

Résumé

Objectif

Le maintien de l'apparence d'une peau jeune est vivement souhaité par une grande proportion de la population mondiale. L'objectif de la présente étude était donc d'évaluer l'effet sur les rides de la peau, d'une combinaison d'ingrédients rapportés à influer sur les facteurs clés impliqués dans le vieillissement de la peau, à savoir l'inflammation, la synthèse du collagène et le stress oxydatif / UV. Une boisson supplémentée a été élaborée contenant des isoflavones de soja, le lycopène, la vitamine C et la vitamine E et donnée aux femmes ménopausées avec une capsule contenant de l'huile de poisson.

Méthode

Nous avons effectué une étude clinique humaine contrôlée randomisée en double aveugle afin de déterminer si ce cocktail d'ingrédients alimentaires pouvait améliorer considérablement l'apparence des rides du visage.

Résultats

Nous avons montré que cette combinaison unique de micronutriments peut réduire considérablement la profondeur des rides du visage et que cette amélioration est associée à un dépôt de nouvelles fibres de collagène dans le derme.

Conclusion

Cette étude montre que la consommation d'un mélange d'isoflavones de soja, de lycopène, de la vitamine C et de la vitamine E et de l'huile de poisson est capable d'induire une amélioration cliniquement mesurable dans la profondeur des rides du visage après utilisation à long terme. Nous avons également montré, pour la première fois avec un produit oral, que l'amélioration est associée à une augmentation du dépôt de nouvelles fibres de collagène dans le derme.

Keywords: collagen synthesis, oral supplement, post-menopausal women, skin physiology, wrinkle reduction

Introduction

The maintenance of youthful skin appearance is strongly desired by a large proportion of the world's population. Skin, like all organs of the body, undergoes alterations due to the passage of time and changes are primarily characterized by a loss of elasticity, increased roughness, uneven skin tone and the appearance of wrinkles. The prevalence of pruritus also increases in aged skin, reflecting poor hydration, impaired skin barrier and altered neural function 1,2.

The underlying biological mechanisms that give rise to these symptoms are numerous, including changes in dermal extracellular matrix (ECM) turnover, increases in inflammatory status and reduction in blood flow. Skin wrinkling in particular arises, in part, from atrophy of the dermal layer of which type I collagen is the major component. This protein is by far the most abundant in human skin, comprising more than 90% of its dry weight and it confers structural integrity on the skin 3. With increasing age, the amount and integrity of collagen in skin is reduced, a process that is further enhanced in photodamage 4. This decline is brought about by increased expression of collagen-degrading matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) with age, coupled with the failure to replace the damaged collagen with newly synthesized protein 5.

The period of most rapid decline in skin quality is around the menopause, with the dramatic decline in circulating oestrogen correlating strongly with loss of dermal collagen and contributing significantly to pronounced skin atrophy, dryness and sensitivity 6, along with decreased elasticity and wrinkle formation 7. Furthermore, the positive effects of oestrogen replacement on skin have been demonstrated in clinical studies that have shown that hormone replacement therapy (HRT) greatly improves the skin of menopausal women 8,9. Increased collagen content, dermal thickness and elasticity have also been demonstrated 10.

Because many of the age-associated changes in skin occur deep in the dermis, they are often difficult to influence with topical products. Effective delivery of nutrients through the diet to the lower region of the skin, particularly to the collagen-producing dermal fibroblasts, is therefore an attractive option. There has been an increasing amount of evidence in recent years showing the potential effects of diet on skin ageing, with new insights into the relationship between food intake and skin appearance beginning to emerge 11,12.

There is now convincing evidence from in vitro, animal and human studies that dietary constituents can afford an important degree of endogenous photoprotection and may therefore be presumed to help reduce skin photoageing. Whilst the level of sun protection (measured as the sun protection factor; SPF) with an SPF 2 to 4 is considerably lower than that afforded by topical sun creams with an SPF of 5 to >50, over a lifetime systemic dietary, photoprotection is still expected to contribute very significantly to overall improved skin appearance.

The ability of a nutrient to provide systemic photoprotection requires it to have one or more of the following functions: prevent the absorption of UV light by skin, protect target molecules by acting as an antioxidant scavenger, induce cellular repair systems or suppress cellular responses such as inflammation. Vitamins such as vitamin C and vitamin E 13–16, carotenoids (E.g. lycopene) 17–22 and n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids 23,24 have all been shown to provide photoprotective benefits, following oral consumption and are believed to operate through one or more of the above mechanisms. Carotenoids are highly effective scavengers of singlet oxygen 25,26, whilst n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids have been shown to influence inflammation in skin through down regulation of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and leukotriene B4 (LTB4) 27–29. Both vitamin E and vitamin C form part of the skin's natural defence against reactive oxygen species and their interaction is thought to be particularly important in the protection of skin against photo-oxidation 30. Vitamin C is also an essential cofactor in the biosynthesis of collagen, an important process in the prevention of skin ageing 31.

Given the association of oestrogen levels with deterioration in skin quality at menopause, plant-derived compounds that are able to mimic oestrogen have also received much attention as potential anti-ageing nutrients. These so-called phytoestrogens have been described as a partial alternative to HRT, due to their ability to bind to and activate the oestrogen receptor 32,33. Activation of this receptor has also been associated with induction of collagen synthesis by dermal fibroblasts 34. Phytoestrogens are believed to offer potential therapies for hormonal-dependent conditions, including the menopause, without the unwanted side effects associated with HRT 35. Indeed, epidemiological studies have indicated a strong correlation between the consumption of soya products in the Far East, containing high levels of phytoestrogens and reduced incidence of hormone-related diseases, including some menopausal symptoms 36–38. In addition to their hormonal-like effect, dietary phytoestrogens have also been reported to exert their effects via non-hormonal mechanisms 39. It is therefore hypothesized that long-term consumption of foods containing phytoestrogens may exert anti-ageing effects in post-menopausal women, including alleviation of skin-associated symptoms.

The aim of the present study was therefore to evaluate the effect on skin wrinkling, of a combination of ingredients reported to influence key factors involved in skin ageing; namely inflammation, collagen synthesis and oxidative/UV stress. A supplemented drink was therefore developed containing soy isoflavones, lycopene, vitamin C and vitamin E and given to post-menopausal women with a capsule containing fish oil.

Post-menopausal women are considered a useful cohort to study, with respect to skin ageing, as the quality of skin declines dramatically in women following the menopause. Any intervention aimed at correcting the symptoms of skin ageing are therefore likely to have a greater effect in this target population.

Materials and methods

Randomized controlled study

The study was double-blind and placebo-controlled and conducted by ProDERM Institute for Applied Dermatological Research (Hamburg, Germany) between January and July 2006.

Eligible subjects were healthy, non-smoking, post-menopausal females (skin type I-III as described by the Fitzpatrick skin type scale 40) who were not receiving HRT, not using dietary supplements and with a BMI between 18 and 33 kg m−2. Power calculations for the smallest difference between the treatments were performed by bootstrapping data of sample sizes of 101 individuals from a previous double-blind placebo-controlled study with identical primary objectives 41. These calculations indicated that a sample size of 50 individuals per treatment group would be sufficient to achieve a power of 75%.

Subjects were allocated to treatment groups using a random allocation procedure in SAS (SAS Institute Inc., Cary NC, U.S.A). The randomization was stratified by age, BMI and time at menopause. Study sponsors, investigators and statisticians remained blind to the treatment allocation to avoid bias during data analysis. Subjects were randomized into three groups of equal size in a parallel design. Two arms of the study were given a combination of drinks and capsules containing differing dose levels of the active ingredients. The third arm was given placebo drinks & capsules, containing no active ingredients. Test products were a combination of a fruit-based drink containing vitamin C, vitamin E, lycopene and isoflavones and capsules containing omega-3 EFA. The respective doses are outlined in Table1.

Table 1.

Study treatments and active ingredient doses

| Active ingredient | mg per daily dose | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo group | Test group 1 | Test group 2 | |

| Total isoflavone (expressed as aglycone) | 0 | 70 (43) | 40 (25) |

| Lycopene | 0 | 8 | 3 |

| Vitamin C | 0 | 250 | 180 |

| Vitamin E | 0 | 250 | 30 |

| Omega-3 EFA's (23% EPA:16% DHA) | 0 | 660 | 660 |

| Dose (quantity per day) | |||

| 100 mL drink | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Soft gel capsules | 2 | 2 | 2 |

Subjects were asked to consume one dose of the study treatment per day for 14 weeks. Non-invasive skin measurements were taken at baseline (T1) and week 15 (T15) along with blood samples, following a minimum 6-h fast, to assess plasma nutrient status. In addition, 3-mm full thickness punch biopsies were taken at baseline and at the end of the study to assess skin quality.

The Freiburger Ethik-Kommission International GmbH approved the study and all subjects gave written and informed consent. All the subjects were monitored for the occurrence of serious adverse events up to, and including, 28 days after their involvement with this study.

Study outcomes

The primary endpoint of the study was the measurement of wrinkle depth around the crow's foot area of the eye. This was assessed by: (i) PRIMOS analysis of Silflo replicas taken according to manufacturer's guidelines and (ii) high-quality photography (Fuji S2 Pro Digital camera). In addition, skin firmness and elasticity (Courage & Khazaka Cutometer® CM825), barrier function and skin hydration (Dermalab® TEWL), skin colour (Konica Minolta Chromameter CR300) and histological biopsy analyses (collagen and elastin) were also measured.

Punch biopsies, at baseline (T1) and following 14 weeks intervention (T15), were obtained and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C prior to analysis. The biopsies were defrosted and fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin before being sectioned. Tissue was then stained with H&E and evaluated by a blinded, independent histopathologist for scored, qualitative changes in the quantity and quality of collagen and elastin fibres.

Analysis of vitamin and carotenoid levels in blood samples was performed by the Scottish Trace Element and Micronutrient Reference Laboratory at the Glasgow Royal Infirmary using standard HPLC methods. Triglyceride and isoflavone analyses were carried out at Unilever R&D Colworth using Fatty Acid Methyl Ester-Gas Chromatography (FAME-GC) analysis and automated immunoassay methods, respectively 42,43.

Study products

Study drinks were prepared on behalf of Unilever at Crown Package Ltd, U.K. Drinks (100 mL units) were supplemented with the required level of individual actives, except those used for the placebo group. The capsules were produced by EuroCaps Ltd. Active capsules contained Omega-3 fish oil (Marinol C38; 23% EPA and 16% DHA) and placebo capsules contained sunflower oil (high oleic). To preserve study blinding, all test and placebo products were of similar appearance and were packaged and labelled in an identical way.

Statistical analyses

Study data were analysed using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with change from baseline after 14 weeks used as the response variable and the treatment group as the fixed effect of interest. Baseline, age and BMI were included in the model as covariates and results considered significant if P < 0.05 (95% confidence interval) as calculated using standard methodology for least-squares means (LSMEAN) within SAS.

A per-protocol analysis set with extreme outliers excluded separately for each parameter was defined prior to the treatment code being broken. A log-transformation was applied to the raw data and subsequently the change from baseline calculated for T15. This was included in a general linear mixed model as the dependent variable with the treatment as the three-level fixed effect of interest. Fixed continuous covariate terms were included for log (baseline) and the stratification variables age, BMI and time since menopause. Estimates were obtained for the least-squares means for the dependent variable for each treatment and also for the differences between test group 1/test group 2 and placebo. P-values for the differences were calculated and adjusted for multiplicity within each model using a Dunnett's correction. In a post-hoc analysis, the interaction of treatment effect with the baseline wrinkle R3z scores, measured by PRIMOS, was also analysed.

Clinical assessment of biopsies

Differences in the quantity and quality of collagen and elastin in the skin of subjects receiving the placebo and test group 2 products over 14 weeks were assessed visually. Analysis was performed blinded from an independent histopathologist who documented changes in the quantity (i.e. changes in the number of orderly reticular collagen bundles and increases in branch-like elastin fibrils) and quality (such as fibre expansion/regression of collagen and arrangement/orientation of elastin fibrils seen above the capillary plexus). Each panellist was scored for a decrease (−1), maintenance (0) or increase (+1) in the level of collagen and/or elastin over the study period. The significance was assessed using a Fisher's exact test, to give an overall P-value.

Results

Subject characteristics

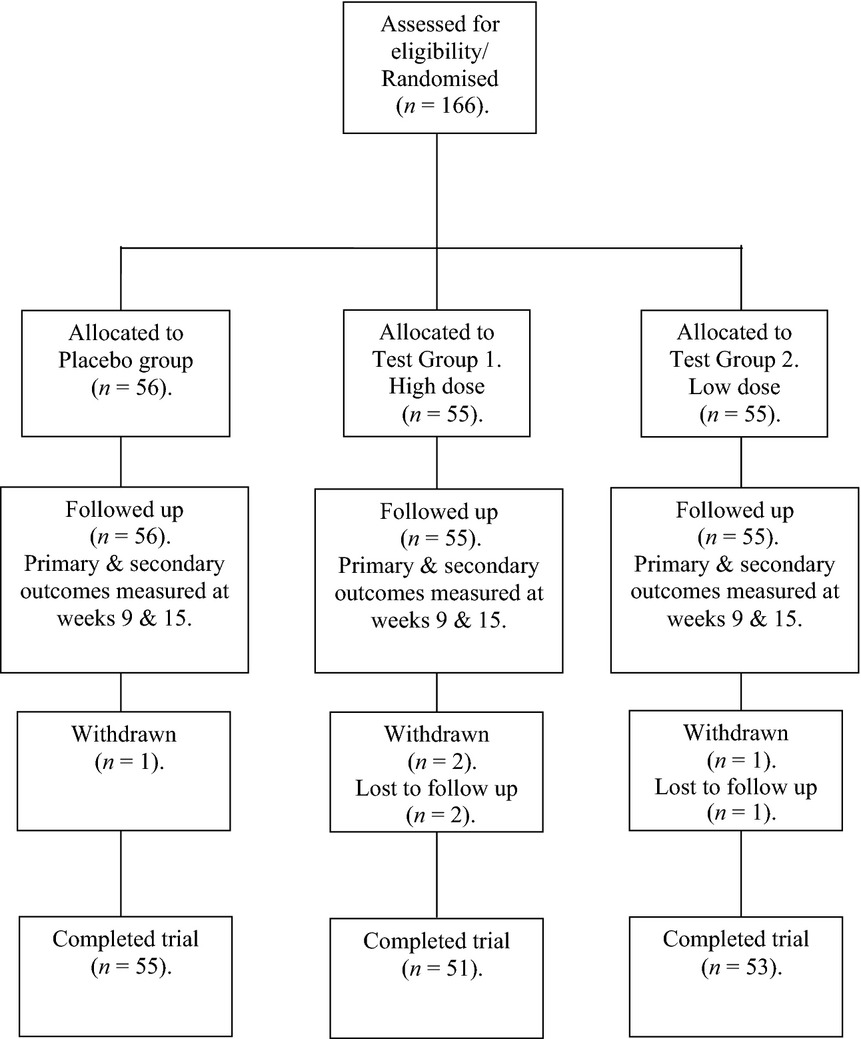

One-hundred and sixty six post-menopausal women were recruited onto the study and were subsequently randomized into three equal treatment arms (a study flow chart is outlined in Table2). Baseline demographics for all treatment groups are indicated in Table3. Dropout rates were low, with only three subjects lost to follow-up and four withdrawn due to poor compliance or voluntary withdrawal. A total of 159 subjects completed the study and no serious adverse events were recorded.

Table 2.

Study flow chart

Table 3.

Mean subject demographics at screening (range)

| Placebo group | Test group 1 | Test group 2 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of subjects: | 56 | 55 | 55 | |

| Age (years) | 61 (45–71) | 61 (49–71) | 61 (48–70) | N.S |

| Years post-menopausal | 13 (2–19) | 12 (2–34) | 13 (3–30) | N.S |

| BMI | 27 (18–33) | 27 (19–33) | 27 (19–33) | N.S |

Study compliance and uptake of functional ingredients

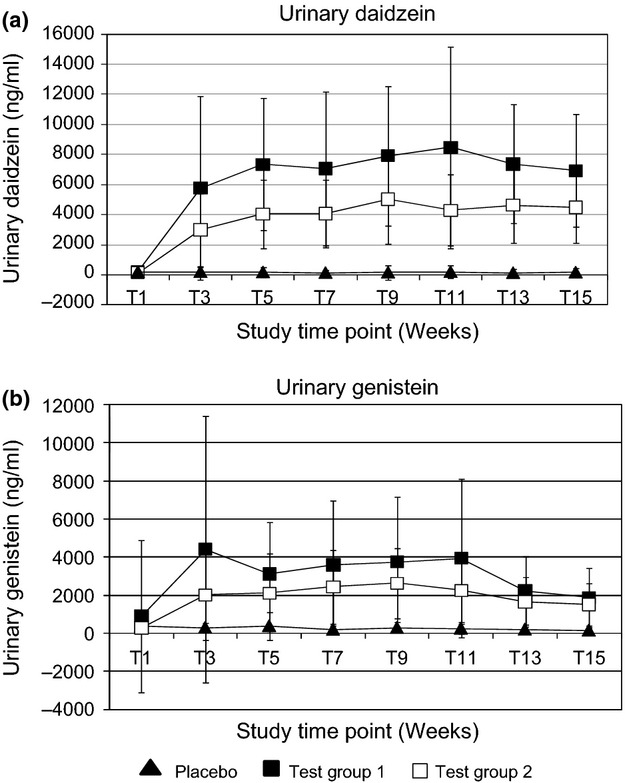

Compliance, as assessed by urinary isoflavone concentration at fortnightly intervals, was considered to be good throughout the study. Mean urinary isoflavone levels, detected in 24-h urine samples, were significantly higher in the test groups compared to placebo for the duration of the study (P < 0.001). In addition, a difference could be observed between the two active treatments at all time points after baseline (P < 0.01), with subjects on test group 1 consistently demonstrating higher excretion of both daidzein and genistein (Fig.1).

Figure 1.

Analysis of Urinary Isoflavones (mean + standard deviation). (a) ng/ml urinary daidzein (b) ng/ml urinary genistein. Significance tested with students t-test and considered significant if P < 0.05 (95% confidence interval).

The plasma levels of all active ingredients measured are also detailed in Table4. Data show that all active ingredients were effectively absorbed into the bloodstream and again indicate that compliance was good throughout the study.

Table 4.

Mean ingredient plasma levels (standard deviation)

| Mean plasma levels | Placebo group | Test group 1 | Test group 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin C (μM) | |||

| T1 | 55.07 (15.66) | 59.50 (16.8) | 56.85 (17.8) |

| T9 | 52.80 (15.05) | 74.64 (19.54)*† | 72.37 (13.93)*† |

| T15 | 55.00 (13.22) | 72.30 (17.06)*† | 72.46 (14.56)*† |

| Vitamin E (μM) | |||

| T1 | 34.44 (7.45) | 34.60 (9) | 38.50 (10)†‡ |

| T9 | 34.85 (7.28) | 50.10 (14)*† | 46.90 (13)*† |

| T15 | 36.30 (7.58) | 50.90 (13)*† | 47.20 (11)*† |

| Lycopene (μg L−1) | |||

| T1 | 114.94 (65.76) | 108.71 (77) | 124.00 (75) |

| T9 | 120.50 (74.09) | 234.70 (104)*†‡ | 179.20 (70)*†‡ |

| T15 | 100.87 (61.00) | 254.40 (103)*†‡ | 201.4 (75)*†‡ |

| Plasma EPA (μg mL−1) | |||

| T1 | 43.37 (26.11) | 42.91 (28.59) | 44.40 (41.2) |

| T15 | 42.98 (21.36) | 67.32 (26.45)*† | 71.09 (28.28)*† |

| Plasma DHA (μg mL−1) | |||

| T1 | 80.20 (26.86) | 76.25 (29.37) | 80.36 (23.69) |

| T15 | 82.69 (25.10) | 97.54 (31.18)*† | 103.56 (33.36)*† |

Significant difference from baseline (T1): P < 0.05.

Significant difference from placebo (within time point): P < 0.05.

Significant difference from other active treatment (within time point): P < 0.05.

Non-invasive skin measures

Wrinkle replica analysis

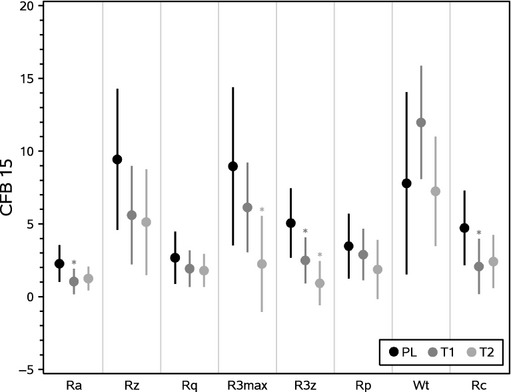

At the end of the study, silflo replicas collected of the crow's foot area of both sides of the face were analysed using standard Phaseshift Rapid In-vivo Measurement Of Skin (PRIMOS) optical 3D technology 44. Data were generated for a number of roughness parameters appropriate to the 3D profile characterization of the skin 45,46 as summarized in a means plot analysis (Fig.2).

Figure 2.

Means plot + Standard Error of the Mean (SEM). PRIMOS analysis generates quantitative data for several parameters with relation to the 3D profile of the skin including Ra, Rz, Rq, R3Max, R3z, Rp, Wt and Rc. Placebo (PL), Test group 1 (T1) and Test group 2 (T2).

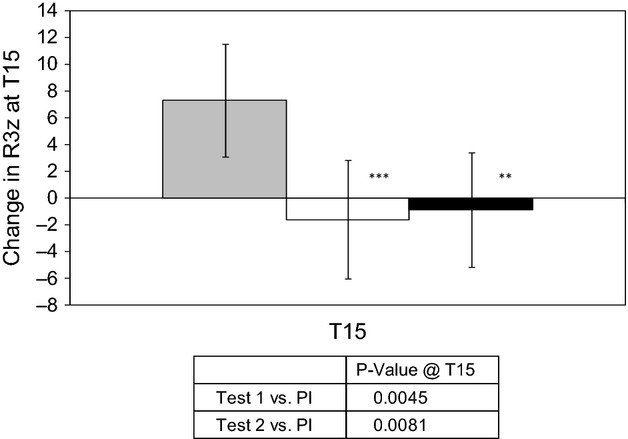

Statistically significant changes were observed over 14 weeks in several of the parameters, indicating that the test groups generally experienced a reduced severity of skin roughness compared with the placebo group over the same period. In particular, the change in R3z value over 14 weeks in both test groups was significantly reduced compared with placebo (Fig.3). This parameter is considered to be one of the primary indicators of wrinkle depth 47, and the changes observed support a significant reduction in average wrinkle depth in both test groups compared with placebo.

Figure 3.

Mean Replica R3z values, expressed as change from baseline (CFB T15-T1). Values are mean ± standard deviation. Placebo (grey), Test group 1 (white), Test group 2 (black). Significance is displayed vs. placebo using ANOVA (** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.005).

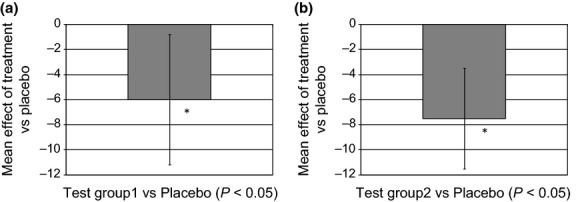

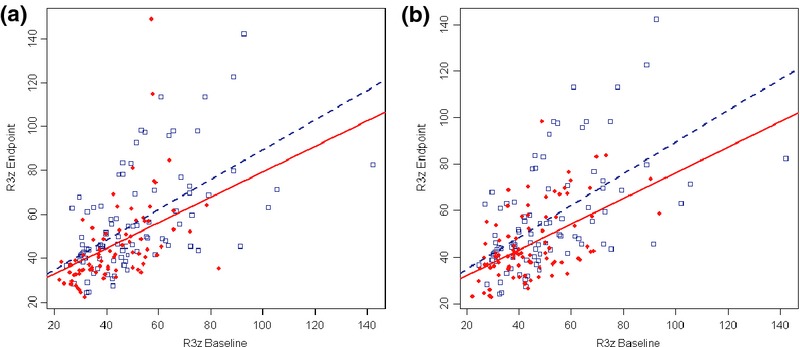

The mean treatment effect on R3z value for both test groups was also examined, and this analysis showed a statistically significant effect (P < 0.05) of both groups when compared with placebo (Fig.4). Furthermore, in a post-hoc analysis, the interaction effect of treatment and baseline R3z was also assessed. As seen in Fig.5, the gradients of the best-fit lines are distinct and separate to the greatest extent at higher baseline R3z values, with the relationship being clearly significant for test group 2 (P = 0.01). This interaction highlights that treatment with the active ingredients had a stronger effect on deeper wrinkles.

Figure 4.

Mean treatment effect on R3z value. (a) Test group1 vs. Placebo (*P < 0.05). (b) Test group2 vs. Placebo (*P < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Best fit lines of treatment-baseline interaction on R3z. (a) Test group1 vs. Placebo (P = 0.057). (b) Test group2 vs. Placebo (P = 0.01).

Firmness & elasticity

Skin elasticity was measured using a Courage & Khazaka Cutometer (probe aperture size 8 mm) at baseline and week 15 on the inner & outer forearm. However, there was no statistical difference from baseline or between placebo and test treatment at any time point in any of the parameters measured (data not shown).

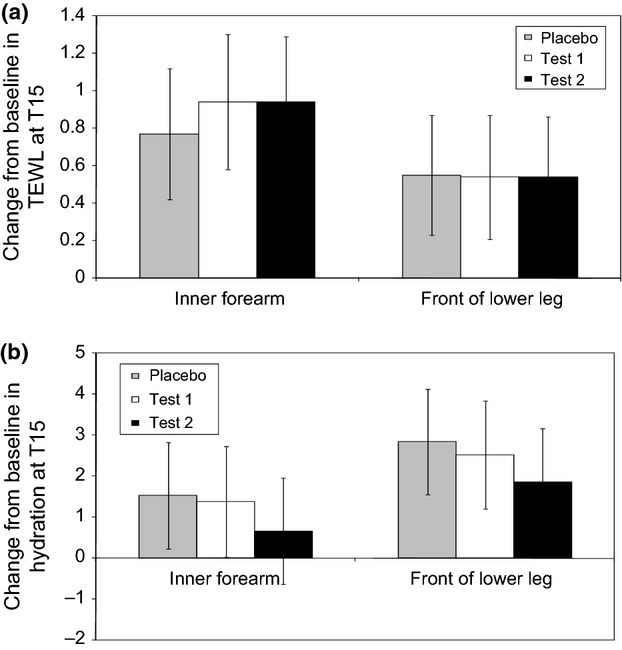

Barrier function & skin hydration

Transepidermal water loss (TEWL) and hydration were also measured at baseline and after 14 weeks of intervention. There was a significant increase from baseline in TEWL with all treatments and at both test sites (Fig.6a). This was not unexpected as seasonal differences in skin barrier integrity have previously been documented 48. However, no significant difference was observed between test and placebo. Similarly, hydration also increased from baseline with all treatments and at both sites measured, but no statistical significance was observed between test and placebo (Fig.6b).

Figure 6.

(a) Change from baseline - TEWL results. Results are displayed as mean change from baseline ± 95% confidence interval (b) Change from baseline – Corneometer results (Hydration). Results are displayed as mean change from baseline ± 95% confidence interval.

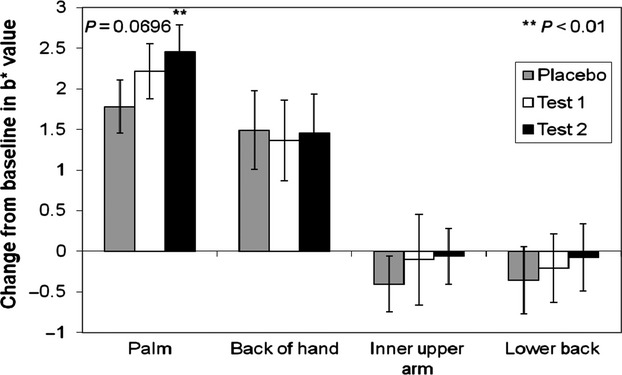

Skin colour

The Minolta Chromameter allows for the objective determination of skin colour using the tristimulus L a* b* system, and increases in b* values are commonly associated with the accumulation of carotenoids in the skin 49. Measurements were taken at baseline and after 14 weeks of intervention, and higher b* values were observed in test groups, particularly within areas of the skin with high levels of subcutaneous fat (such as the palm and lower back) (Fig.7). This data strongly indicates an accumulation of dermal carotenoids in the skin following 14 weeks of intervention 50.

Figure 7.

Minolta chromameter b* values expressed as change from baseline (T15-T1). Values are mean CFB and 95% confidence interval. Statistical significance (**) is displayed vs. placebo using ANOVA (palm & lower back).

There was no evidence of a significant treatment effect at any site for L and a* values (skin lightness and blood flow, respectively).

Biopsy analysis

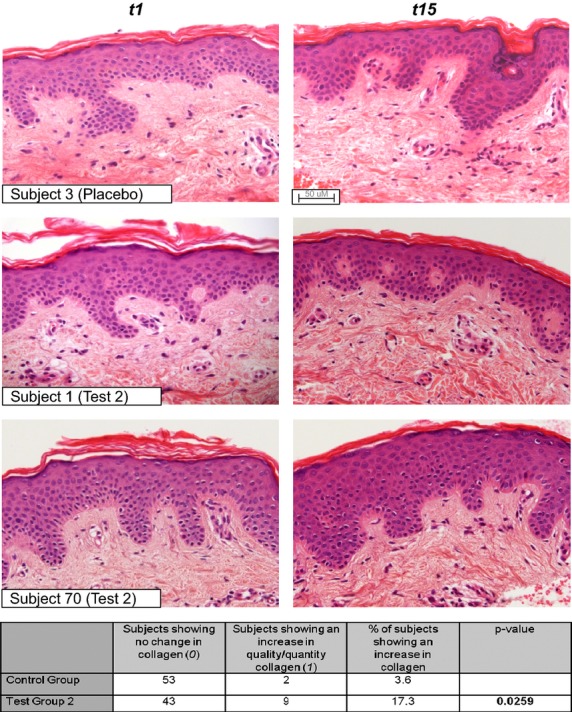

Following evaluation from an independent histopathologist, a significant number of individuals in test group 2 demonstrated an increase in collagen quantity and quality in biopsies after 14 weeks compared with those on the placebo treatment when examined by Fisher's exact test (Fig.8). Given the high number of individuals recruited into each cell and the time-consuming nature of the histological evaluation, biopsies from individuals on test group 1 treatment were not analysed for changes in collagen levels. No significant differences were observed in elastin quantity and/or quality between control and test group 2.

Figure 8.

Examples of H&E staining in three individuals. Table summarises an independent evaluation from a blinded histopathologist. Test group 2 shows a statistically significant increase in quality and/or quantity of collagen after 14 weeks (P = 0.0259).

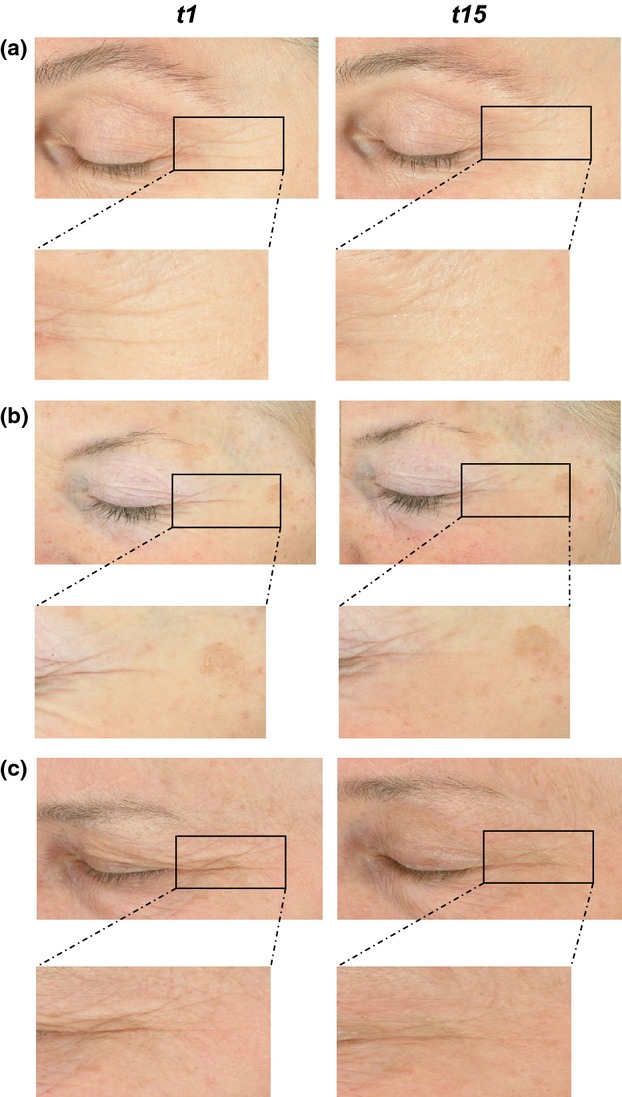

Digital photography

High-quality photography was taken at the beginning (T0) and end of the study (T15). Examples of subjects are shown in Fig.9.

Figure 9.

Examples of high quality digital photography with a Fuji S2 Pro Digital camera and two Nikon flashes (SB80DX) in three individuals from test group 2.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to establish that a unique combination of ingredients given through the diet would have a significant benefit on skin wrinkle formation in a population of post-menopausal Caucasian women. We have shown that a combination of isoflavones, omega-3 fatty acids, lycopene, vitamin C and vitamin E when consumed orally for 14 weeks can significantly reduce the depth of facial wrinkles. We have also demonstrated, for the first time with an oral product, that the improvement is associated with increased deposition of new collagen fibres.

We have performed a double-blind randomized controlled investigation to assess whether a combination of dietary ingredients, selected for their proposed skin anti-ageing benefits, can significantly improve the appearance of facial wrinkles. The study was conducted following the principles of international good clinical practice standards, with products coded and randomized at source and with subjects, investigators and statistician remaining ‘blind’ to the coding until the study and initial data analysis were complete.

We observed no benefit of the test or placebo products on skin colour, hydration or barrier quality. However, we did demonstrate that individuals consuming the active test products showed significantly improved skin texture and reduced wrinkle depth when compared with the placebo group. On average, there was a 10% reduction in wrinkle depth in the test group when compared with placebo.

Interestingly, we also demonstrated a baseline interaction effect with regard to wrinkle depth and response to treatment, that is, the deeper the wrinkle the greater the reduction in depth after 14 weeks. This potentially highlights the mechanistic action of the treatment. The smaller wrinkles as measured by PRIMOS technology are most likely a result of surface changes in the upper epidermal layers, whilst deeper wrinkles are potentially caused by alterations in the deeper dermal layer of skin. Any nutritional intervention therefore, taken orally is likely to have a greater effect on this latter type of wrinkle, so individuals with deeper wrinkles will experience the greatest benefit.

Interest in the role of specific food ingredients on promoting optimal skin condition has grown considerably in the past few years, with new insights into the relationship between food intake and skin health beginning to emerge. There are now comprehensive clinical data demonstrating the photoprotective benefits of dietary carotenoids 51,52 vitamins E & C 13,14 and fish oil (containing EPA and DHA) 27,28. Furthermore, recent studies have indicated that oral intake of soy isoflavone aglycones appears to improve the aged skin of middle-aged women 53–55.

In addition, we examined the distribution of collagen in skin samples taken at the beginning and end of the study. Collagen is the main structural protein of the skin, and the abrupt onset of visible skin ageing around the menopause is primarily the consequence of a lower production of collagen, the supportive protein network of the skin 56–58.

We found that a significantly higher number of individuals consuming the test product (test group 2) showed increased levels of collagen in skin biopsies after 14 weeks, than those who consumed placebo products. To our knowledge, this is the first published report of increased collagen production in skin as a result of an oral intervention.

A reduction in the level of collagen synthesis and general decline in the quality of existing collagen has been reported to contribute greatly to the increase in wrinkles and loss of firmness associated with ageing skin 59. To obtain real wrinkle reduction effects therefore, matrix rejuvenation would be needed. The increase in collagen observed provides a potentially underlying reason for the reduction in wrinkle depth demonstrated in the study.

The ability of the ingredients described here to induce skin collagen is further supported by evidence from previously published studies. Cultured human fibroblasts in vitro treated with an isoflavone soy-containing extract demonstrated an increased level of collagen synthesis 60, whilst mice fed dietary soy isoflavones also showed increased deposition of collagen in their skin 61. In addition, there are numerous reports of omega-3 fatty acids influencing collagen production in ligaments and connective tissue cells 62,63. Furthermore, addition of omega-3 fatty acids to mouse 3T3 cells in vitro has also been shown to be associated with enhanced collagen synthesis 64. More recently, increased levels of collagen were also detected in human skin following topical application of omega-3 fatty acids 65.

Surprisingly, in this investigation, we were unable to detect any significant changes between the quantity and quality of elastin fibres between test and placebo groups. In fact, detailed histological evaluation revealed that the papillary microfibril scaffolds of elastin were already well organized and uniform in distribution and excellent in condition. These histological observations may provide further support to the lack of beneficial effects we observed between test and placebo firmness and elasticity measurements.

In conclusion, we believe that the combination of ingredients, rather than the level of each individual active, is the most important aspect for the overall functionality of the mix and that this study demonstrates that consumption of these specific nutritional ingredients is able to induce a clinically measureable improvement in the depth of facial wrinkles following long-term use. This improvement is associated with increased deposition of newly formed collagen in the dermis of panellists consuming the active combination.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Thomas Brenn, Edinburgh Dermatopathology, for expert visual examination and quantitation of histological samples and Winfried Theis and Tony Dadd, Unilever Data Science, for statistical analyses and interpretation.

Sources of funding

Unilever R&D Colworth funded the research.

Conflict of interest

All the authors are employees of the industrial funder of this research (Unilever R&D Colworth).

References

- 1.Garibyan L, Chiou AS, Elmariah SB. Advanced aging skin and itch: addressing an unmet need. Dermatol. Ther. 2013;26:92–103. doi: 10.1111/dth.12029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jenkins G. Molecular mechanisms of skin ageing. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2002;123:801–810. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(01)00425-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisher GJ, Varani J, Voorhees JJ. Looking older: fibroblast collapse and therapeutic implications. Arch. Dermatol. 2008;144:666–672. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.5.666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baroni Edo R, Biondo-Simões Mde L, Auersvald A, et al. Influence of aging on the quality of the skin of white women: the role of collagen. Acta Cir. Bras. 2012;27:736–740. doi: 10.1590/s0102-86502012001000012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varani J, Dame MK, Rittie L, et al. Decreased collagen production in chronologically aged skin. Am. J. Pathol. 2006;168:1861–1868. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah MG, Maibach HI. Estrogen and skin. An overview. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2001;2:143–150. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200102030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolognia JL, Braverman IM, Rousseau ME, Sarrel PM. Skin changes in menopause. Maturitas. 1989;11:295–304. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(89)90026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piérard GE, Letawe C, Dowlati A, Piérard-Franchimont C. Effect of hormone replacement therapy for menopause on the mechanical properties of skin. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1995;43:662–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb07202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunn LB, Damesyn M, Moore AA, et al. Does oestrogen prevent skin aging? Results from the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch. Dermatol. 1997;133:339–342. doi: 10.1001/archderm.133.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevenson S, Thornton J. Effect of estrogens on skin aging and the potential role of SERMs. Clin. Interv. Aging. 2007;2:283–297. doi: 10.2147/cia.s798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jenkins G, Wainwright LJ, Green MR. Nutrition and skin ageing. In: Stanner S, Thompson R, Buttriss JL, editors. Healthy Ageing: The Role of Nutrition and Lifestyle. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. pp. 107–124. Chapter 7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cosgrove M, Jenkins G. Nutrition and skin aging. In: Rhein LD, Fluhr JW, editors. Aging Skin: Current and Future Therapeutic Strategies. Illinois: Allured books; 2010. pp. 377–394. Chapter 13. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuchs J, Kern H. Modulation of UV-light-induced skin inflammation by D-alpha-tocopherol and L-ascorbic acid: a clinical study using solar simulated radiation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1998;25:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eberlein-König B, Placzek M, Przybilla B. Protective effect against sunburn of combined systemic ascorbic acid (vitamin C) and d-alpha-tocopherol (vitamin E) J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1998;38:45–48. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70537-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.La Ruche G, Césarini JP. Protective effect of oral selenium plus copper associated with vitamin complex on sunburn cell formation in human skin. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 1991;8:232–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Werninghaus K, Meydani M, Bhawan J, et al. Evaluation of the photoprotective effect of oral vitamin E supplementation. Arch. Dermatol. 1994;130:1257–1261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith-Warner SA, Elmer PJ, Tharp TM, et al. Increasing vegetable and fruit intake: randomized intervention and monitoring in an at-risk population. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9:307–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heinrich U, Wiebusch M, Tronnier H. Photoprotection from ingested carotenoids. Cosm. Toilet. 1998;113:61–70. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heinrich U, Gartner C, Wiebusch M, et al. Supplementation with ß-carotene or a similar amount of mixed carotenoids protects humans from UV-induced erythema. J. Nutr. 2003;133:98–101. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.1.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stahl W, Heinrich U, Wiseman S, et al. Dietary tomato paste protects against Ultraviolet Light-Induced Erythema in Humans. J. Nutr. 2001;131:1449–1451. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.5.1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stahl W, Heinrich U, Jungmann H, et al. Increased dermal carotenoid levels assessed by non-invasive reflection spectrophotometry correlate with serum levels in women ingesting Betatene. J. Nutr. 1998;128:903–907. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.5.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aust O, Stahl W, Sies H, et al. Supplementation with tomato-based products increases lycopene, phytofluene and phytoene levels in human serum and protects against UV-light-induced erythema. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2005;75:54–60. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831.75.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rhodes LE, Shahbakhti H, Azurdia RM, et al. Effect of eicosapentaenoic acid, an omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid, on UVR-related cancer risk in humans. An assessment of early genotoxic markers. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:919–925. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orengo IF, Black HS, Wolf JE. Influence of fish oil supplementation on the minimal erythema dose in humans. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 1992;284:219–221. doi: 10.1007/BF00375797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sies H, Stahl W, Sundquist AR. Antioxidant functions of vitamins Vitamins E and C, beta-carotene, and other carotenoids. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1992;669:7–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb17085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Handelman GJ. The evolving role of carotenoids in human biochemistry. Nutrition. 2001;17:818–822. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(01)00640-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rhodes LE, O'Farrell S, Jackson MJ, Friedmann PS. Dietary fish-oil supplementation in humans reduces UVB-erythemal sensitivity but increases epidermal lipid peroxidation. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1994;103:151–154. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12392604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rhodes LE, Durham BH, Fraser WD, Friedmann PS. Dietary fish oil reduces basal and ultraviolet B-generated PGE2 levels in skin and increases the threshold to provocation of polymorphic light eruption. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1995;105:532–535. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12323389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pilkington SM, Watson RE, Nicolaou A, Rhodes LE. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids: photoprotective macronutrients. Exp. Dermatol. 2011;20:537–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2011.01294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wefers H, Sies H. The protection by ascorbate and glutathione against microsomal lipid peroxidation is dependent on vitamin E. Eur. J. Biochem. 1988;174:353–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb14105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pinnel SR, Murad S, Darr D. Induction of collagen synthesis by ascorbic acid. A possible mechanism. Arch. Dermatol. 1987;123:1684–1686. doi: 10.1001/archderm.123.12.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Albertazzi P, Purdie D. The nature and utility of the phytoestrogens: a review of the evidence. Maturitas. 2002;42:173–185. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(02)00024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Maturitas. 2008;61:214–226. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cassidy A. Potential risks and benefits of phytoestrogen-rich diets. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2003;73:120–126. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831.73.2.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Surazynski A, Jarzabek K, Haczynski J, et al. Differential effects of estradiol and raloxifene on collagen biosynthesis in cultured human skin fibroblasts. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2003;12:803–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Setchell KD, Cassidy A. Dietary isoflavones: biological effects and relevance to human health. J. Nutr. 1999;129:758S–767S. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.3.758S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.North American Menopause Society. The role of soy isoflavones in menopausal health: report of The North American Menopause Society/Wulf H. Utian Translational Science Symposium in Chicago, IL (October 2010) Menopause. 2011;18:732–753. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31821fc8e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Welty FK, Lee KS, Lew NS, et al. The association between soy nut consumption and decreased menopausal symptoms. J. Women's Health (Larchmt) 2007;16:361–369. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ho SC, Woo J, Lam S. Soy protein consumption and bone mass in early postmenopausal Chinese women. Osteoporos. Int. 2003;14:835–842. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1453-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wei H, Saladi R, Lu Y, et al. Isoflavone genistein: photoprotection and clinical implications in dermatology. J. Nutr. 2003;133(Supplement 1):3811S–3819S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.11.3811S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fitzpatrick TB. Soleil et peau. J. Med. Esthet. 1975;2:33034. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wainwright LJ, Barrett KE, Casey J, et al. Effect of a novel supplemented drink on skin aging: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2010;130(Supplement 1):S48. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Masood A, Stark KD, Salem K., Jr A simplified and efficient method for the analysis of fatty acid methyl esters suitable for large clinical studies. J. Lipid Res. 2005;46:2299–2305. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D500022-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Talbot DC, Ogborne RM, Dadd T, et al. Monoclonal antibody-based time-resolved fluorescence immunoassays for daidzein, genistein, and equol in blood and urine: application to the Isoheart intervention study. Clin. Chem. 2007;53:748–756. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.075077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leveque JL. EEMCO guidance for the assessment of skin topography. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 1999;12:103–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fujimura T, Haketa K, Hotta M, et al. Global and systematic demonstration for the practical usage of a direct in vivo measurement system to evaluate wrinkles. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2007;29:423–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2494.2007.00399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grove GL, Grove MJ. Effects of topical retinoids on photoaged skin measured by optical profilometry. Methods Enzymol. 1990;190:360–371. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)90042-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jacobi U, Chen M, Frankowski G, et al. In vivo determination of skin surface topography using an optical 3D device. Skin Res. Technol. 2004;10:207–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0846.2004.00075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Conti A, Rogers J, Verdejo P, et al. Seasonal influences on stratum corneum ceramide 1 fatty acids and the influence of topical essential fatty acids. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 1996;18:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2494.1996.tb00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alaluf S, Heinrich U, Stahl W, et al. Dietary carotenoids contribute to normal human skin color and UV photosensitivity. J. Nutr. 2002;132:399–403. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.3.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stahl W, Heinrich U, Jungmann H, et al. Increased dermal carotenoid levels assessed by non-invasive reflection spectrophotometry correlate with serum levels in women ingesting Betatene. J. Nutr. 1998;128:903–907. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.5.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mathews-Roth MM, Pathak MA, Parrish J, et al. A clinical trial of the effects of oral beta-carotene on the responses of human skin to solar radiation. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1972;59:349–353. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12627408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Césarini JP, Michel L, Maurette JM, et al. Immediate effects of UV radiation on the skin: modification by an antioxidant complex containing carotenoids. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2003;19:182–189. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0781.2003.00044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Izumi T, Saito M, Obata A, et al. Oral intake of soy isoflavone aglycone improves the aged skin of adult women. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2007;53:57–62. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.53.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Skovgaard GR, Jensen AS, Sigler ML. Effect of a novel dietary supplement on skin aging in post-menopausal women. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006;60:1201–1206. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thom E. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study on the clinical efficacy of oral treatment with DermaVite on ageing symptoms of the skin. J. Int. Med. Res. 2005;33:267–272. doi: 10.1177/147323000503300301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brincat M, Kabalan S, Studd JW, et al. A study of the decrease of skin collagen content, skin thickness, and bone mass in the postmenopausal woman. Obstet. Gynecol. 1987;70:840–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Affinito P, Palomba S, Sorrentino C, et al. Effects of postmenopausal hypoestrogenism on skin collagen. Maturitas. 1999;33:239–247. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(99)00077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Adamiak A, Skorupski P, Rechberger T, Jakowicki JA. The expression of the gene encoding pro-alpha 1 chain of type I collagen in the skin of premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2000;93:9–11. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(00)00251-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McGrath JA, Eady RAJ, Pope FM. Anatomy and organization of human skin. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2004. pp. 3.1–3.84. 7th edn Chapter 3. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Südel KM, Venzke K, Mielke H, et al. Novel aspects of intrinsic and extrinsic aging of human skin: beneficial effects of soy extract. Photochem. Photobiol. 2005;81:581–587. doi: 10.1562/2004-06-16-RA-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim SY, Kim SJ, Lee JY, et al. Protective effects of dietary soy isoflavones against UV-induced skin-aging in hairless mouse model. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2004;2:157–162. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2004.10719356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jia Y, Turek JJ. Altered NF-kappaB gene expression and collagen formation induced by polyunsaturated fatty acids. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2005;16:500–506. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hankenson KD, Watkins BA, Schoenlein IA, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids enhance ligament fibroblast collagen formation in association with changes in interleukin-6 production. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 2000;223:88–95. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1373.2000.22312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jia Y, Turek JJ. Polyenoic fatty acid ratios alter fibroblast collagen production via PGE2 and PGE receptor subtype response. Exp. Biol. Med (Maywood) 2004;229:676–683. doi: 10.1177/153537020422900712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim HH, Cho S, Lee S, et al. Photoprotective and anti-skin-aging effects of eicosapentaenoic acid in human skin in vivo. J. Lipid Res. 2006;47:921–930. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500420-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]