Abstract

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a major public health problem worldwide. Although nucleos(t)ide analogs inhibiting viral reverse transcriptase are clinically available as anti‐HBV agents, emergence of drug‐resistant viruses highlights the need for new anti‐HBV agents interfering with other targets. Here we report that cyclosporin A (CsA) can inhibit HBV entry into cultured hepatocytes. The anti‐HBV effect of CsA was independent of binding to cyclophilin and calcineurin. Rather, blockade of HBV infection correlated with the ability to inhibit the transporter activity of sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP). We also found that HBV infection‐susceptible cells, differentiated HepaRG cells and primary human hepatocytes expressed NTCP, while nonsusceptible cell lines did not. A series of compounds targeting NTCP could inhibit HBV infection. CsA inhibited the binding between NTCP and large envelope protein in vitro. Evaluation of CsA analogs identified a compound with higher anti‐HBV potency, having a median inhibitory concentration <0.2 μM. Conclusion: This study provides a proof of concept for the novel strategy to identify anti‐HBV agents by targeting the candidate HBV receptor, NTCP, using CsA as a structural platform. (Hepatology 2014;59:1726–1737)

Abbreviations

- CN

calcineurin

- CsA

cyclosporin A

- CyPs

cyclophilins

- HBs

viral envelope protein

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HCVpp

HCV pseudoparticles

- IFN

interferon

- LHBs

large envelope protein

- MDR

multidrug resistance

- MHBs

middle envelope protein

- MRP

MDR‐related protein

- NTCP

sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide

- PHH

primary human hepatocytes

- PPIase

peptidyl prolyl cis/trans‐isomerase

- SHBs

small envelope protein

- TCA

taurocholic acid

- TUDCA

tauroursodeoxycholic acid

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a substantial public health problem, affecting ∼350 million people worldwide.1, 2, 3 HBV‐infected patients have an elevated risk for developing liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Currently, clinical treatment for HBV infection includes interferon alpha (IFN‐α) and nucleos(t)ide analogs. IFN‐α therapy yields long‐term clinical benefit in only less than 40% of patients and can cause significant side effects. Nucleos(t)ide analog treatment can suppress HBV replication and is accompanied by substantial biochemical and histological improvement; however, it may select for drug‐resistant viruses, which limit the efficacy of long‐term treatment. To overcome these problems, the development of new anti‐HBV agents targeting a different step of the HBV life cycle is urgently needed.

As HBV has only one viral gene encoding an enzymatic activity, the polymerase, there is no apparent strategy to develop a new class of antiviral agents other than polymerase inhibitors. Hence, it is important to define alternative molecular targets for anti‐HBV agents as well as to identify potential anti‐HBV compounds.3, 4 Myrcludex‐B is a peptide mimicking pre‐S1, which is crucial for the virus‐cell membrane interaction. Pretreatment with this peptide has been shown to prevent virus entry and spread of virus infection.5, 6 Phenylpropenamide derivatives and heteroaryl‐pyrimidines (HAP) suppressed HBV replication through capsid disassembly.7, 8, 9, 10 Although the development of the former was discontinued because of significant toxicity,3 HAP exhibited anti‐HBV efficacy in the absence of robust toxicity.8, 10 Deoxynojirimycin derivatives are iminosugars that inhibit alpha‐glucosidases. Although treatment with these compounds suppressed HBV secretion in both cell culture and mouse models,11, 12 further investigation will be required to assess their anti‐HBV efficacy and the specificity to HBV. Thus, it is an attractive strategy to identify a cellular factor that is specifically involved in HBV infection and relevant for the development of anti‐HBV agents.

Cyclosporin A (CsA) is an immunosuppressant clinically used for suppression of the immunological failure of xenograft tissues. CsA primarily targets cellular peptidyl prolyl cis/trans‐isomerase (PPIase) cyclophilins (CyPs).13 The resultant CsA/CyP complex subsequently binds to and inhibits calcineurin (CN), a phosphatase that dephosphorylates nuclear factor of activated T cell (NF‐AT) to allow nuclear translocation and transactivation of downstream genes. This CN inhibition contributes to the suppression of immune responses. In addition, CsA is known to inhibit the transporter activity of membrane transporters, including the multidrug resistance (MDR) and MDR‐related protein (MRP) families.14 Previously, we demonstrated that CsA and its nonimmunosuppressive derivatives suppress hepatitis C virus (HCV) replication,15, 16 with the anti‐HCV activity being mediated by the inhibition of CyPs.17, 18, 19 Currently, a series of drugs classified as CyP inhibitors are in clinical development for treatment of HCV‐infected patients.20, 21

In this study we report that CsA and its analogs inhibited HBV entry through a CyP‐independent mechanism. We established a screening system that can identify small molecules inhibiting HBV entry. Screening in this system revealed that CsA blocked HBV entry. The anti‐HBV activity of CsA was not correlated with binding to CyPs and CN. CsA inhibited the transporter activity of sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP), a recently reported candidate for the HBV entry receptor,22 and interrupted the binding between NTCP and large envelope protein in vitro. Other NTCP inhibitors also blocked HBV infection. Analog testing identified CsA‐related compounds with higher anti‐HBV potency than CsA. Thus, CsA and NTCP inhibitors can be used as a platform to develop a novel class of anti‐HBV agents.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

HepaRG (Biopredic), HepAD38 (kindly provided by Dr. Christoph Seeger at Fox Chase Cancer Center), and primary human hepatocytes (PHHs) (Phoenixbio) were cultured as described previously.23

HBV Preparation and Infection

The HBV used in this study was mainly derived from the culture supernatant of HepAD38 cells. HBV infection was performed as described previously.23 More detailed procedures are given in the Supporting Information.

Indirect Immunofluorescence Analysis, Real‐Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), Southern Blot Analysis, 3‐(4,5‐Dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)−2,5‐diphenyltetrazolium Bromide (MTT) Assays, and Reporter Assays

Indirect immunofluorescence analysis, real‐time PCR, southern blot analysis, MTT assays, and reporter assays were performed essentially as described.23 More detailed procedures are given in the Supporting Information.

Detection of HBs and HBe Antigens

HBs antigen was quantified by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described previously.23 HBe antigen was detected by a Chemiluminescent Immuno‐Assay (Mitsubishi Chemical Medience).

HCV Pseudoparticle Assay

The HCV pseudoparticles (HCVpp), which reproduce HCV envelope‐mediated entry, were generated by transfecting the expression plasmids for MLV Gag‐Pol, HCV E1E2, and a luciferase that can be packaged into the virion (kindly provided by Dr. Francois‐Loic Cosset at the University of Lyon) into 293T cells. HCVpp recovered from the culture supernatant of transfected cells were used in a HCV entry assay as described previously.24

Transporter Assay

The transporter activity of NTCP was assayed essentially as described25 using 293 (Sekisui Medical) and HepG2 cells permanently overexpressing human NTCP. Briefly, the cells were preincubated with compounds at 37°C for 15 minutes and then incubated with radiolabeled substrate, [3H]taurocholic acid (TCA), at 37°C for 5 minutes to allow substrate uptake into the cells. The cells were then washed and lysed to measure the accumulated radioactivity. In this assay, we did not observe cytotoxic effects of compounds at any of the concentrations tested. More detailed procedures are given in the Supporting Information.

AlphaScreen Assay

Recombinant NTCP and HBs proteins, which were tagged with 6xHis and biotin, respectively, were synthesized using a wheat cell‐free protein system as described previously.26 Protein‐protein interactions were detected using the AlphaScreen IgG (ProteinA) detection kit (PerkinElmer) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Briefly, the recombinant tagged proteins were incubated with streptavidin‐coated donor beads and anti‐6xHis antibody‐conjugated acceptor beads that generate a luminescence signal when brought into proximity by binding to interacting proteins. Luminescence was analyzed with the AlphaScreen detection program of an Envision spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer). More detailed procedures for the AlphaScreen assay are described in the Supporting Information.

Additional experimental procedures are included in the Supporting Information.

Results

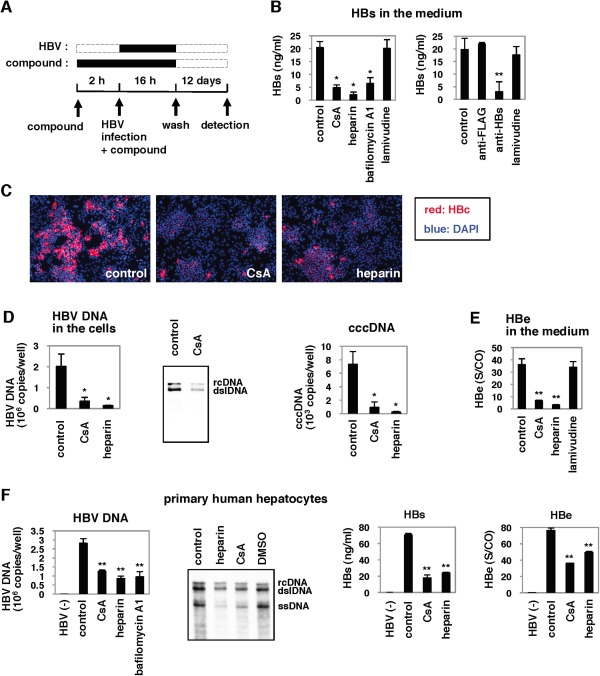

Cyclosporin A Blocked HBV Infection

We focused on HBV entry and established a cell culture system to evaluate this step in HBV infection. To identify small molecules inhibiting HBV entry, we pretreated HepaRG cells27 with compounds for 2 hours, then added a HBV inoculum and continued incubation with compounds for 16 hours (Fig. 1A). After washing out free HBV and compounds, the cells were cultured for an additional 12 days in the absence of compounds (Fig. 1A). For robust chemical screening, HBV infection was monitored by the viral envelope protein (HBs) level secreted from the infected cells at 12 days postinfection by ELISA. This assay could identify heparin, an HBV attachment inhibitor,28, 29 and bafilomycin A1, a v‐type H+ ATPase inhibitor that blocks acidification of vesicles and HBV entry,30 but not lamivudine, a reverse transcriptase inhibitor,31 as compounds reducing HBs protein level in the medium (Fig. 1B). In addition, use of an anti‐HBs antibody to neutralize viral entry, but not use of an anti‐FLAG antibody, reduced viral protein secreted from the HBV‐infected cells (Fig. 1B). Thus, this system is likely to evaluate the effect of compounds on the early phase of the HBV life cycle, including attachment and entry, but not effects on HBV replication. A chemical screen with this system revealed that CsA reduced HBs secretion from HBV‐infected cells (Fig. 1B). Treatment with CsA significantly decreased HBc protein expression (Fig. 1C) and HBV DNA as well as cccDNA (Fig. 1D) in the cells and HBe in the medium (Fig. 1E), without causing cytotoxicity (Supporting Fig. S1A). This effect of CsA was not limited to infection of HepaRG cells, as we observed a similar anti‐HBV effect of CsA for PHHs (Fig. 1F). The anti‐HBV effect of CsA was also observed on HBV infection of PHHs in the absence of PEG8000 (Fig. S1B), indicating that the effect of CsA did not depend on PEG8000, which was normally included in the HBV infection experiments. These data suggest that CsA blocked HBV infection.

Figure 1.

Cyclosporin A (CsA) blocked HBV infection. (A) Schematic representation of the schedule for exposing HepaRG cells to compounds and HBV. HepaRG cells were pretreated with compounds for 2 hours and then inoculated with HBV for 16 hours. After washing out the free HBV and compounds, the cells were cultured with the medium in the absence of compounds for an additional 12 days to quantify HBs protein secreted from the infected cells into the medium. Black and dotted bars indicate the interval for treatment and without treatment, respectively. (B) CsA 4 μM, heparin 25 U/mL, bafilomycin A1 200 nM, lamivudine 1 μM, anti‐FLAG 10 μg/mL, and anti‐HBs antibody 10 μg/mL, were tested for effect on HBV infection according to the protocol shown in (A). (C‐E) HBc protein (C), HBV DNAs, and cccDNA (D) in the cells as well as HBe antigen in the medium (E) at 12 days postinfection according to the protocol shown in (A) were detected by immunofluorescence, real‐time PCR analysis, southern blot, and ELISA. Red and blue in (C) show the detection of HBc protein and nuclear staining, respectively. (F) PHHs were treated with the indicated compounds and infected with HBV using the protocol shown in (A). The levels of HBV DNAs in the cells, as well as of HBs and HBe antigens in the medium, were determined. Statistical significance was determined using the Student t test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

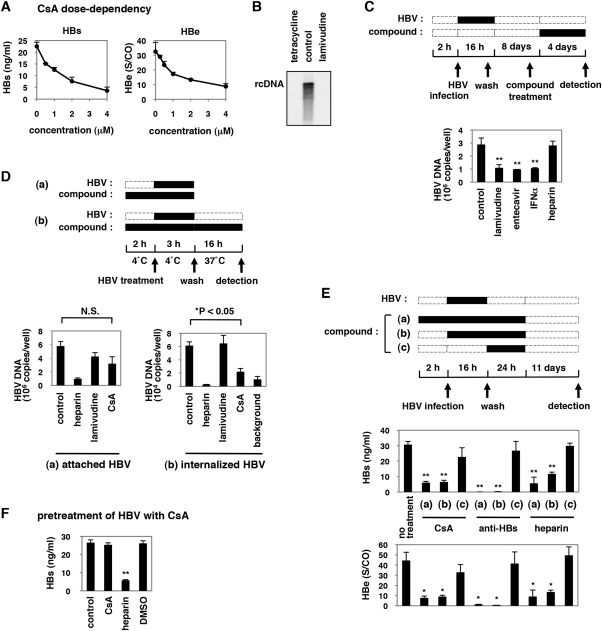

Effect of Cyclosporin A on HBV Entry

CsA decreased HBs and HBe secreted from the infected cells in a dose‐dependent manner (Fig. 2A). We next investigated which step in the HBV life cycle was blocked by CsA. The HBV life cycle can be divided into two phases: the early phase of infection including attachment, entry, nuclear import, and cccDNA formation, and the following late phase representing HBV replication that includes transcription, assembly, reverse transcription, and viral release.32 Lamivudine drastically decreased HBV DNAs in HepAD38 cells,33 which reproduce HBV replication but not the early phase of infection (Fig. 2B). In addition, continuous treatment with lamivudine as well as entecavir and interferon‐α for 4 days after HBV infection could decrease HBV DNA levels in HBV‐infected HepaRG cells, which suggests an inhibition of HBV replication (Fig. 2C). Nevertheless, lamivudine did not show an anti‐HBV effect when applied only prior to and during HBV infection (Fig. 1A,B), suggesting that the anti‐HBV compounds identified in Fig. 1A interrupted the early phase of the HBV life cycle.

Figure 2.

CsA reduced internalized HBV. (A) HepaRG cells were treated with or without various concentrations of CsA (0.5, 1, 2, and 4 μM) as shown in Fig. 1A. HBV infection was monitored by HBs and HBe secretion. (B) HBV DNA in core particles was detected by southern blot analysis of DNA extracts from HepAD38 cells treated for 6 days with or without tetracycline 0.5 μg/mL and lamivudine 1 μM. (C) Upper scheme indicates the treatment schedule of HepaRG cells with compounds and HBV. HepaRG cells were infected with HBV for 16 hours. After washing out the input virus, cells were cultured in the absence of compounds for 8 days. The cells were then cultured with compounds (lamivudine 1 μM, entecavir 1 μM, IFN‐α 100 IU/mL, or heparin 25 U/mL) for 4 days and recovered for detection of HBV DNA. Black and dotted boxes indicate the periods with and without treatment, respectively. Lower graph shows the quantified relative HBV DNA level in cells treated according to the above scheme. (D) Upper scheme shows the experimental procedure for examining the attached and internalized HBV. (a) The cells were pretreated with compounds (heparin 25 U/mL, lamivudine 1 μM, or CsA 4 μM) at 4°C for 2 hours and then treated together with HBV at 4°C for 3 hours to allow HBV attachment to the cells. After washing out the free virus, cell surface HBV DNA was extracted and quantified by real‐time PCR. (b) After attachment of HBV at 4°C for 3 hours and the following wash, the cells were cultured in the presence or absence of compounds at 37°C for 16 hours to allow the cells to internalize bound HBV. The cells were then trypsinized and extensively washed prior to quantifying the cellular HBV DNA. The lower graphs show the level of HBV DNA attached to the cells (a) and internalized inside the cells (b). “Background” in (b) indicates the signal from cells incubated at 4°C, instead of 37°C, for 16 hours after washing out the virus in (b), which shows the background signal level of the assay. (E) The upper scheme shows the procedure for the time of addition experiment. Compounds (CsA 4 μM, anti‐HBs antibody 10 μg/mL, or heparin 25 U/mL) were applied beginning 2 hours prior to HBV infection (a), beginning during HBV infection (b), or beginning immediately after HBV infection (c) until 24 hours postinfection. HBs and HBe protein secretion were measured at 12 days postinfection. Middle and lower graphs indicate HBs and HBe secretion, respectively, from the cells treated according to the above scheme. (F) Preincubation of HBV with compounds. HBV was preincubated with the indicated compounds for 30 minutes at 37°C. Compounds were then removed by ultrafiltration. The recovered compound‐treated HBV was used to infect HepaRG cells (16 hours incubation), and HBV infection was monitored with HBs antigen secreted into the medium at 12 days postinfection. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, N.S., not significant.

We then examined whether CsA inhibited attachment or entry. For evaluating HBV attachment,34 cell surface HBV DNA was extracted and quantified from HepaRG cells exposed to HBV at 4°C for 3 hours and then washed (Fig. 2D‐a). For the internalization assay,34 the above cells, after washing, were further cultured at 37°C for 16 hours to allow HBV to internalize into the cells, and then trypsinized to digest HBV remaining on the cell surface to allow quantification of internalized HBV DNA (Fig. 2D‐b). CsA slightly reduced the amount of attached HBV DNA, although the effect was not statistically significant (Fig. 2D‐a). In contrast, CsA caused a significant reduction of HBV DNA in the internalization assay (Fig. 2D‐b). In the time of addition assay as shown in Fig. 2E, treatment with CsA during HBV infection decreased HBs and HBe production (Fig. 2E‐b), while CsA did not have an anti‐HBV effect when delivered after HBV infection (Fig. 2E‐c). Thus, CsA appears to primarily block the entry step including internalization. To examine whether CsA targeted HBV particles or host cells, we preincubated HBV with CsA and then purified the CsA from the HBV inoculum, followed by measurement of the HBV infectivity using HepaRG cells (Fig. 2F). Preincubation with CsA did not affect HBV infectivity, in contrast to the antagonizing effect of heparin to HBV particles (Fig. 2F), suggesting that CsA did not affect HBV particles but rather targeted host cells.

Cyclosporin A Showed a Pan‐Genotypic Anti‐HBV Effect

We examined the anti‐HBV effect of CsA on the infection of different genotypes of HBV into PHHs. As shown in Fig. 3A, CsA reduced the infection of HBV genotype A, C, or D, which differ in sequences from the virus strain used in all of the other figures. However, CsA did not affect the entry of HCV, in contrast to the inhibition of HCV entry by heparin, bafilomycin A1, or an anti‐HCV E2 antibody (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

CsA showed a pan‐genotypic anti‐HBV effect. (A) PHHs were treated with compounds (CsA 4 μM or heparin 25 U/mL) according to the scheme in Fig. 1A with different genotypes of HBV inoculum, and either HBs protein in the medium or HBV DNA in the cells at 12 days postinfection was quantified. (B) CsA did not affect the entry of HCV. Huh‐7.5.1 cells were pretreated with the indicated compounds for 1 hour and then infected with HCVpp for 4 hours. At 72 hours postinfection, intracellular luciferase activity was measured. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, N.S., not significant.

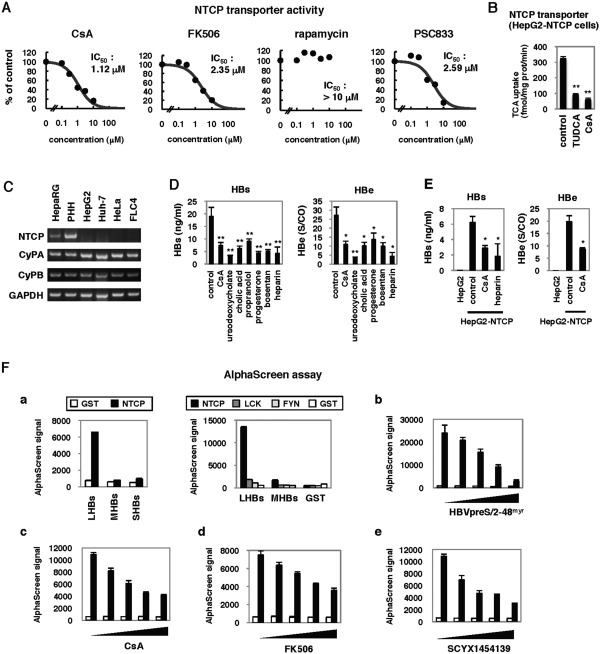

Effect of Immunosuppressants on HBV Infection

CsA is used clinically as an immunosuppressant, such as in patients following liver transplantation.13 We therefore investigated the activity of other immunosuppressants on HBV infection. Among the additional immunosuppressive drugs examined, only FK506 was able to suppress HBV infection (Fig. 4A). CsA is known to have three major cellular targets: cellular cyclophilins (CyPs), calcineurin (CN), and transporters including MDRs and MRPs.18 Although both CsA and FK506 can inhibit CN (Fig. 4B), this activity was dispensable for the anti‐HBV effect, as PSC833, a CsA derivative inactive for CN inhibition (Fig. 4B),18 could still inhibit HBV infection (Fig. 4C). As PSC833 and FK506 did not bind to the active site of CyPs (Fig. 4D), CyP inhibition is not likely to be responsible for the anti‐HBV activity.

Figure 4.

Effect of immunosuppressants on HBV infection. (A,C) HepaRG cells were treated with or without the indicated compounds at 2 μM (FK506 4 μM) in (A), and CsA (2 and 4 μM) and PSC833 (2 and 4 μM) in (C), according to the scheme in Fig. 1A. HBs (A,C) and HBe (C) secretion was determined. (B) Effect of compounds on the activity of the calcineurin/NF‐AT pathway. Jurkat cells transfected with pNF‐AT‐luc and pRL‐TK were stimulated with PMA and ionomycin in the presence or absence of CsA, FK506, and PSC833 for 24 hours to measure the luciferase activity. (D) Cyclophilin binding activity of CsA, FK506, and PSC833 was determined in a competitive binding assay as described in the Materials and Methods using a CsA‐derived fluorescent probe. IC50s (μM) for the inhibition of probe binding to CyPA, CyPB, and CyPD are shown. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

CsA Blocked HBV Infection Through Targeting NTCP

Recently, NTCP was reported as a candidate entry receptor for HBV.22 A transporter activity assay showed that CsA inhibited the activity of NTCP both in 293 (Fig. 5A) and HepG2 cells (Fig. 5B) engineered to stably overexpress NTCP, as previously reported.35 CsA was also suggested to bind to NTCP on the membrane in a ligand binding assay using HepG2‐NTCP cells (Fig. S2).

Figure 5.

NTCP inhibitors blocked HBV infection. (A) NTCP transporter activity was examined following CsA, FK506, rapamycin, and PSC833 treatment of 293 cells overexpressing NTCP, as described in the Materials and Methods. Dose‐response curves and IC50s for inhibition of NTCP transporter activity are shown. (B) NTCP transporter activity was measured in HepG2‐NTCP cells treated with or without CsA 10 μM or tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA) 10 μM as a positive control. (C) Expression of mRNAs for NTCP, CyPA, CyPB, and GAPDH in HepaRG, PHHs, HepG2, Huh‐7, HeLa, and FLC4 cells was determined by RT‐PCR. (D) HepaRG cells were treated with or without CsA 4 μM, ursodeoxycholate 100 μM, cholic acid 100 μM, propranolol 100 μM, progesterone 40 μM, bosentan 100 μM, and heparin 25 U/mL according to the scheme in Fig. 1A. Secretion of HBs and HBe was quantified. (E) HepG2 cells overexpressing NTCP (HepG2‐NTCP) and the parental HepG2 cells were pretreated with or without CsA or heparin for 2 hours, then treated with HBV for 16 hours. HBV infection was monitored with HBs and HBe secreted from the cells. (F) AlphaScreen assay to evaluate the binding between NTCP and large envelope protein (LHBs) as described in the Materials and Methods. (a) Left, His‐tagged GST (white bars) or NTCP (black bars) are incubated with large (LHBs), middle (MHBs), or small envelope protein (SHBs). Right, His‐tagged NTCP and other nonrelevant proteins, LCK and FYN, and GST were incubated with LHBs, MHBs, and GST. (b‐e) His‐tagged GST (white bars) or NTCP (black bars) were incubated with LHBs in the presence of varying amounts of pre‐S1 lipopeptide HBVpreS/2‐48myr (b; 0, 7.7, 15.3, 30.7, and 61.3 μM), CsA (c; 0, 37.5, 75, 150, and 300 μM), FK506 (d; 31, 63, 125, 250, and 500 μM), and SCYX1454139 (e; 0, 37.5, 75, 150, and 300 μM), respectively. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

NTCP messenger RNA (mRNA) was expressed in HepaRG cells and PHH, which are HBV‐susceptible, while little to no expression was detected in HBV‐nonsusceptible cell lines including HepG2, Huh‐7, FLC4, and nonhepatocyte HeLa cells (Fig. 5C). In contrast, CyPA and CyPB were expressed in all of these cell lines, irrespective of infection susceptibility. Intriguingly, we found that the inhibition of NTCP transporter activity correlated with anti‐HBV entry activity (Figs. 5A, 4A,B). These results suggest the possibility that compounds targeting NTCP have the potential to block HBV infection. To test this prediction, we treated HepaRG cells with compounds known to inhibit NTCP, including ursodeoxycholate, cholic acid, propranolol, progesterone, and bosentan35, 36 to investigate the effect on HBV entry using the protocol in Fig. 1A. As shown in Fig. 5D, these compounds inhibited HBV infection. Thus, inhibition of NTCP blocked HBV infection. We also showed that HepG2 cells overexpressing NTCP were susceptible to HBV infection (Fig. 5E), as reported recently.22 Treatment with CsA also reduced HBs and HBe secretion when these cells were infected with HBV (Fig. 5E), suggesting that CsA inhibited NTCP‐mediated HBV infection.

The binding of the HBV large envelope protein (LHBs) to NTCP was reported to be important for HBV entry.22 Thus, one mechanism by which compounds that directly inhibit NTCP activity may block HBV entry is interruption of the binding between NTCP and LHBs. To test this possibility, we established an AlphaScreen assay to evaluate LHBs‐NTCP binding in vitro as described in the Materials and Methods. In vitro synthesized NTCP and LHBs were at least partially functional, as NTCP bound to its substrate TCA (Fig. S3A) and LHBs could neutralize HBV infection into HepaRG cells (Fig. S3B). As shown in Fig. 5F, incubation of recombinant NTCP with LHBs but not middle (MHBs) and small envelope protein (SHBs) produced a significant AlphaScreen signal (Fig. 5F‐a, left) indicative of a direct protein‐protein interaction. In contrast to NTCP, recombinant GST or other nonrelevant proteins, LCK and FYN,37 did not produce a binding signal when incubated with LHBs (Fig. 5F‐a), suggesting that our AlphaScreen assay produced a specific signal for the interaction of NTCP with LHBs. Consistent with the report that the pre‐S1 region of LHBs was important for the binding to NTCP,22 the signal was decreased in a dose‐dependent manner by the addition of pre‐S1 lipopeptide HBVpreS/2‐48myr,5 (Fig. 5F‐b) but not of an inactive mutant of pre‐S1 (Fig. S3C), indicating a competition of pre‐S1 with LHBs for NTCP binding. In this assay, CsA as well as FK506 and a CsA derivative, SCYX1454139 (see the next section), were shown to reduce the signal for LHBs‐NTCP binding in a dose‐dependent manner (Fig. 5F‐c,d,e). These results suggest that CsA targets NTCP and thereby inhibits the interaction between LHBs and NTCP.

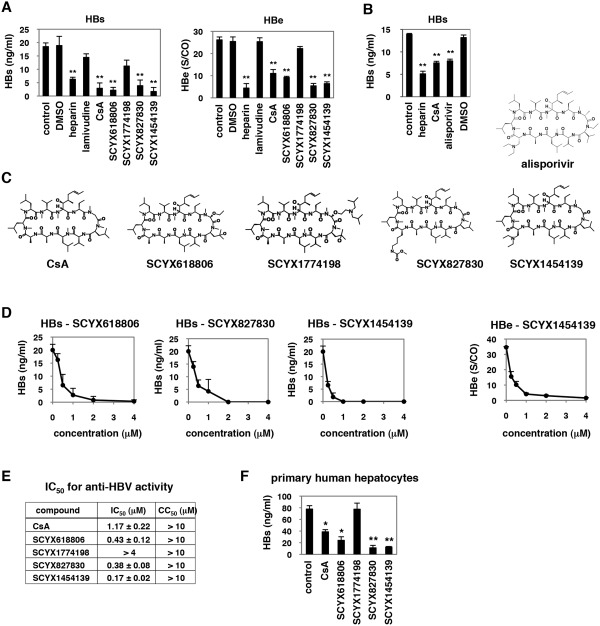

Identification of CsA Analogs Possessing a Higher Anti‐HBV Potential

Considering CsA as a lead compound, we tested CsA analogs for anti‐HBV activity. As shown in Fig. 6A, SCYX618806 reduced HBs secretion after HBV infection, while a related analog SCYX1774198 did not have a significant anti‐HBV effect (Fig. 6A,C). Additional analogs, SCYX827830 and SCYX1454139, had significant anti‐HBV activities (Fig. 6A,C). Alisporivir (Debio 025), an anti‐HCV drug candidate,38 also decreased HBV infection to the equivalent level to CsA (Fig. 6B). Figure 6D shows a dose‐dependent reduction of HBs secretion by treatment with SCYX618806, SCYX827830, and SCYX1454139, all of which had more potent anti‐HBV activities than CsA (compare Fig. 6D with Fig. 2A). These results indicate that anti‐HBV activity is not disrupted by at least some changes to the 3‐glycine, 4‐leucine, and 8‐alanine residues of CsA, although additional analogs will need to be evaluated for a full understanding of the structure‐activity relationships. Notably, SCYX618806 and alisporivir bear modifications on the 4‐leucine residue of the CsA backbone that prevent CN binding and immunosuppressive activity (Table S1), further confirming that anti‐HBV activity does not require immunosuppressive activity. Notably, SCYX1454139 showed the strongest anti‐HBV entry activity among 50 CsA derivatives examined (data not shown and Fig. 6E). The median inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) for anti‐HBV activity as well as CC50s determined by an MTT‐based cell viability assay are shown in Fig. 6E. The IC50 and CC50 of SCYX1454139 were 0.17 ± 0.02 and >10 μM, respectively, a profile superior to that of CsA (IC50 and CC50 of 1.17 ± 0.22 and >10 μM, respectively). Inhibition of HBV infection by treatment with SCYX1454139 was also observed in PHHs, in which also the anti‐HBV effect of SCYX1454139 was more remarkable than that of CsA (Fig. 6F). These results clearly indicate that analogs of CsA may include compounds with greater anti‐HBV potency than that of CsA itself.

Figure 6.

Analysis of CsA analogs. (A,B) Anti‐HBV activity of CsA analogs. HepaRG cells were treated with or without dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), heparin 10 U/mL, lamivudine 1 μM, CsA 4 μM, or its analogs, SCYX618806, SCYX1774198, SCYX827830, and SCYX1454139 (A) or alisporivir (B) at 4 μM, as shown in Fig. 1A to measure HBs and HBe secretion level. (C) Chemical structures of CsA and its derivatives. (D) Dose‐response curves for CsA analogs. HepaRG cells were treated with or without various concentrations of SCYX618806, SCYX827830, or SCYX1454139 (0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 μM) as shown in Fig. 1A. (E) IC50s (μM) for CsA and its analogs in blocking HBV infection are shown. CC50s (μM) determined by the MTT cell viability assay are also shown. (F) PHHs were treated with CsA and its derivatives at 4 μM or left untreated according to the protocol in Fig. 1A, and HBV infection was monitored by HBs protein secretion. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Discussion

Previous reports have demonstrated that CsA suppresses the replication of a variety of viruses including human immunodeficiency virus, HCV, influenza virus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus, human papillomavirus, flaviviruses, vesicular stomatitis virus, and vaccinia virus.16, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46 Virological analyses using CsA further demonstrate that CyPs are involved in the replication of these viruses. In this study, we showed that CsA inhibited the entry of HBV but in an apparent CyP‐independent manner. It was previously reported that CsA suppressed HBV replication in a cell culture system carrying an HBV transgene.47 However, this antireplication effect is not likely to be responsible for the anti‐HBV activity observed in this study, based on several observations. First, the experimental system mainly used in this study (Fig. 1A) is likely to evaluate the early phase of HBV infection but not HBV replication. Second, the suppression of HBV replication by CsA reported previously was mediated by blocking the mitochondrial permeability transition pore possibly through binding to mitochondrial CyPD.47, 48 The anti‐HBV activity shown in this study, however, had no correlation with binding to CyPs, suggesting that the inhibition of HBV infection in HepaRG cells and PHHs is not from the result of suppression of HBV replication. Rather, CsA inhibited NTCP transporter activity and disrupted the binding between NTCP and LHBs in vitro. Moreover, inhibition of HBV infection could be observed by treatment with other compounds having the capacity to inhibit NTCP. These results suggest that targeting NTCP blocks HBV infection.

The current anti‐HBV agents are mainly comprised of nucleos(t)ide analogs and IFNs. Development of anti‐HBV agents targeting different molecules is greatly needed for achieving improved treatment of HBV infection, especially to combat drug‐resistant virus. HBV cell entry mechanisms have been poorly defined. At the initial stage, HBV attaches to target cells with low affinity through binding involving cellular factors including heparan sulfate proteoglycans.28, 29 For the subsequent entry mechanism, it has recently been reported that NTCP is essential for HBV‐specific entry.22 Although the precise mechanism for entry and internalization is as yet incompletely understood, interference with this step has emerged as an attractive approach for development of novel therapeutics. For example, Gripon et al.5 demonstrated that a peptide mimicking the pre‐S1 region of large envelope protein prevented HBV infection in a mouse model. These results suggest that inhibition of virus cell entry could be an effective strategy for preventing HBV infection to achieve clinical outcomes such as for postexposure prophylaxis, blockage of vertical transmission, and prevention of HBV recurrence after liver transplantation. Given that HBV reactivation generally occurs under immunosuppressive conditions,49, 50 it is uncertain whether clinically relevant doses of CsA or FK506 could be helpful in preventing HBV reactivation after liver transplantation. It remains also unknown in general whether entry inhibitors could be effective in eliminating chronic HBV infection. Future studies should evaluate whether inhibition of HBV entry by CsA or its derivatives can reduce persistent HBV infection, especially in combination with nucleos(t)ide analogs or interferons. In this study, we obtained nonimmunosuppressive CsA derivatives that could inhibit HBV entry (Fig. 6). Moreover, a small‐scale analog analysis identified a CsA derivative exhibiting more potent inhibition of HBV infection, with an IC50 of 0.1‐0.2 μM (Fig. 6). This IC50 is equivalent to the anti‐HCV replication activities of alisporivir or SCY‐635 (0.22 μM and 0.08 μM, respectively), drugs which have been shown to reduce HCV viral load in infected patients during clinical trials.38 Further analog analysis using CsA as a platform may identify more potent anti‐HBV compounds.

In general, antiviral drugs targeting a cellular factor select drug‐resistant viruses at a lower frequency than do direct‐acting antiviral agents. Cellular targets relevant for anti‐HBV drug development have been poorly defined to date. This study has demonstrated that small molecules targeting NTCP can inhibit HBV infection. Further study of NTCP inhibitors and CsA derivatives may provide a new anti‐HBV strategy targeting a cellular factor, which is less likely to foster emergence of drug‐resistant viruses.

Supporting information

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgment

HepAD38 and Huh‐7.5.1 cells were kindly provided by Dr. Christoph Seeger at Fox Chase Cancer Center and Dr. Francis Chisari at Scripps Research Institute. Purified CyPA, B, and D were generous gifts from Dr. Gunter Fischer, Max Planck Research Unit for Enzymology of Protein Folding, Halle, Germany. Plasmids for the HCVpp system were the kind gift from Dr. Francois‐Loic Cosset at the University of Lyon. A pre‐S1 lipopeptide HBVpreS/2‐48myr was kindly provided by Dr. Stephan Urban at the University Hospital Heidelberg. We are also grateful to all of the members of Department of Virology II, National Institute of Infectious Diseases.

Potential conflict of interest: A.S., T.D., and K.B.E. are employees of SCYNEXIS, Inc. Y.T. is on the speakers' bureau for and received grants from Bristol‐Myers Squibb and Chugai.

Partly supported by grants‐in‐aid from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, Japan, from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan, and from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

References

- 1. Pawlotsky JM, Dusheiko G, Hatzakis A, Lau D, Lau G, Liang TJ, et al. Virologic monitoring of hepatitis B virus therapy in clinical trials and practice: recommendations for a standardized approach. Gastroenterology 2008;134:405–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rapicetta M, Ferrari C, Levrero M. Viral determinants and host immune responses in the pathogenesis of HBV infection. J Med Virol 2002;67:454–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zoulim F. Hepatitis B virus resistance to antiviral drugs: where are we going? Liver Int 2011;31(Suppl 1):111–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Grimm D, Thimme R, Blum HE. HBV life cycle and novel drug targets. Hepatol Int 2011;5:644–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gripon P, Cannie I, Urban S. Efficient inhibition of hepatitis B virus infection by acylated peptides derived from the large viral surface protein. J Virol 2005;79:1613–1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Petersen J, Dandri M, Mier W, Lutgehetmann M, Volz T, von Weizsacker F, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in vivo by entry inhibitors derived from the large envelope protein. Nat Biotechnol 2008;26:335–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Delaney WEt, Edwards R, Colledge D, Shaw T, Furman P, Painter G, et al. Phenylpropenamide derivatives AT‐61 and AT‐130 inhibit replication of wild‐type and lamivudine‐resistant strains of hepatitis B virus in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2002;46:3057–3060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Deres K, Schroder CH, Paessens A, Goldmann S, Hacker HJ, Weber O, et al. Inhibition of hepatitis B virus replication by drug‐induced depletion of nucleocapsids. Science 2003;299:893–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. King RW, Ladner SK, Miller TJ, Zaifert K, Perni RB, Conway SC, et al. Inhibition of human hepatitis B virus replication by AT‐61, a phenylpropenamide derivative, alone and in combination with (‐)beta‐L‐2',3'‐dideoxy‐3'‐thiacytidine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1998;42:3179–3186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Weber O, Schlemmer KH, Hartmann E, Hagelschuer I, Paessens A, Graef E, et al. Inhibition of human hepatitis B virus (HBV) by a novel non‐nucleosidic compound in a transgenic mouse model. Antiviral Res 2002;54:69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Block TM, Lu X, Mehta AS, Blumberg BS, Tennant B, Ebling M, et al. Treatment of chronic hepadnavirus infection in a woodchuck animal model with an inhibitor of protein folding and trafficking. Nat Med 1998;4:610–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Block TM, Lu X, Platt FM, Foster GR, Gerlich WH, Blumberg BS, et al. Secretion of human hepatitis B virus is inhibited by the imino sugar N‐butyldeoxynojirimycin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994;91:2235–2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Watashi K, Shimotohno K. Cyclophilin and viruses: cyclophilin as a cofactor for viral infection and possible anti‐viral target. Drug Target Insights 2007;2:9–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Loor F, Tiberghien F, Wenandy T, Didier A, Traber R. Cyclosporins: structure‐activity relationships for the inhibition of the human MDR1 P‐glycoprotein ABC transporter. J Med Chem 2002;45:4598–4612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. El‐Farrash MA, Aly HH, Watashi K, Hijikata M, Egawa H, Shimotohno K. In vitro infection of immortalized primary hepatocytes by HCV genotype 4a and inhibition of virus replication by cyclosporin. Microbiol Immunol 2007;51:127–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Watashi K, Hijikata M, Hosaka M, Yamaji M, Shimotohno K. Cyclosporin A suppresses replication of hepatitis C virus genome in cultured hepatocytes. Hepatology 2003;38:1282–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nakagawa M, Sakamoto N, Tanabe Y, Koyama T, Itsui Y, Takeda Y, et al. Suppression of hepatitis C virus replication by cyclosporin a is mediated by blockade of cyclophilins. Gastroenterology 2005;129:1031–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Watashi K, Ishii N, Hijikata M, Inoue D, Murata T, Miyanari Y, et al. Cyclophilin B is a functional regulator of hepatitis C virus RNA polymerase. Mol Cell 2005;19:111–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yang F, Robotham JM, Nelson HB, Irsigler A, Kenworthy R, Tang H. Cyclophilin A is an essential cofactor for hepatitis C virus infection and the principal mediator of cyclosporine resistance in vitro. J Virol 2008;82:5269–5278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schlutter J. Therapeutics: new drugs hit the target. Nature 2011;474:S5–S7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Watashi K. Alisporivir, a cyclosporin derivative that selectively inhibits cyclophilin, for the treatment of HCV infection. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 2010;11:213–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yan H, Zhong G, Xu G, He W, Jing Z, Gao Z, et al. Sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide is a functional receptor for human hepatitis B and D virus. Elife 2012;1:e00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Watashi K, Liang G, Iwamoto M, Marusawa H, Uchida N, Daito T, et al. Interleukin‐1 and tumor necrosis factor‐alpha trigger restriction of hepatitis b virus infection via a cytidine deaminase activation‐induced cytidine deaminase (AID). J Biol Chem 2013;288:31715–31727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nakajima S, Watashi K, Kamisuki S, Tsukuda S, Takemoto K, Matsuda M, et al. Specific inhibition of hepatitis C virus entry into host hepatocytes by fungi‐derived sulochrin and its derivatives. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2013;440:515–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mita S, Suzuki H, Akita H, Hayashi H, Onuki R, Hofmann AF, et al. Inhibition of bile acid transport across Na+/taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (SLC10A1) and bile salt export pump (ABCB 11)‐coexpressing LLC‐PK1 cells by cholestasis‐inducing drugs. Drug Metab Dispos 2006;34:1575–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Takai K, Sawasaki T, Endo Y. Practical cell‐free protein synthesis system using purified wheat embryos. Nat Protoc 2010;5:227–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gripon P, Rumin S, Urban S, Le Seyec J, Glaise D, Cannie I, et al. Infection of a human hepatoma cell line by hepatitis B virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002;99:15655–15660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Leistner CM, Gruen‐Bernhard S, Glebe D. Role of glycosaminoglycans for binding and infection of hepatitis B virus. Cell Microbiol 2008;10:122–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schulze A, Gripon P, Urban S. Hepatitis B virus infection initiates with a large surface protein‐dependent binding to heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Hepatology 2007;46:1759–1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Funk A, Mhamdi M, Hohenberg H, Will H, Sirma H. pH‐independent entry and sequential endosomal sorting are major determinants of hepadnaviral infection in primary hepatocytes. Hepatology 2006;44:685–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. De Clercq E, Ferir G, Kaptein S, Neyts J. Antiviral treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections. Viruses 2010;2:1279–1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Locarnini S, Zoulim F. Molecular genetics of HBV infection. Antivir Ther 2010;15(Suppl 3):3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ladner SK, Otto MJ, Barker CS, Zaifert K, Wang GH, Guo JT, et al. Inducible expression of human hepatitis B virus (HBV) in stably transfected hepatoblastoma cells: a novel system for screening potential inhibitors of HBV replication. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1997;41:1715–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Aizaki H, Morikawa K, Fukasawa M, Hara H, Inoue Y, Tani H, et al. Critical role of virion‐associated cholesterol and sphingolipid in hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol 2008;82:5715–5724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kim RB, Leake B, Cvetkovic M, Roden MM, Nadeau J, Walubo A, et al. Modulation by drugs of human hepatic sodium‐dependent bile acid transporter (sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide) activity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1999;291:1204–1209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Leslie EM, Watkins PB, Kim RB, Brouwer KL. Differential inhibition of rat and human Na+‐dependent taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP/SLC10A1)by bosentan: a mechanism for species differences in hepatotoxicity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2007;321:1170–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Palacios EH, Weiss A. Function of the Src‐family kinases, Lck and Fyn, in T‐cell development and activation. Oncogene 2004;23:7990–8000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Paeshuyse J, Kaul A, De Clercq E, Rosenwirth B, Dumont JM, Scalfaro P, et al. The non‐immunosuppressive cyclosporin DEBIO‐025 is a potent inhibitor of hepatitis C virus replication in vitro. Hepatology 2006;43:761–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bienkowska‐Haba M, Patel HD, Sapp M. Target cell cyclophilins facilitate human papillomavirus type 16 infection. PLoS Pathog 2009;5:e1000524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bose S, Mathur M, Bates P, Joshi N, Banerjee AK. Requirement for cyclophilin A for the replication of vesicular stomatitis virus New Jersey serotype. J Gen Virol 2003;84:1687–1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Damaso CR, Moussatche N. Inhibition of vaccinia virus replication by cyclosporin A analogues correlates with their affinity for cellular cyclophilins. J Gen Virol 1998;79(Pt 2):339–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Liu X, Zhao Z, Li Z, Xu C, Sun L, Chen J, et al. Cyclosporin A inhibits the influenza virus replication through cyclophilin A‐dependent and ‐independent pathways. PLoS One 2012;7:e37277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Luban J, Bossolt KL, Franke EK, Kalpana GV, Goff SP. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein binds to cyclophilins A and B. Cell 1993;73:1067–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pfefferle S, Schopf J, Kogl M, Friedel CC, Muller MA, Carbajo‐Lozoya J, et al. The SARS‐coronavirus‐host interactome: identification of cyclophilins as target for pan‐coronavirus inhibitors. PLoS Pathog 2011;7:e1002331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Qing M, Yang F, Zhang B, Zou G, Robida JM, Yuan Z, et al. Cyclosporine inhibits flavivirus replication through blocking the interaction between host cyclophilins and viral NS5 protein. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009;53:3226–3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Towers GJ, Hatziioannou T, Cowan S, Goff SP, Luban J, Bieniasz PD. Cyclophilin A modulates the sensitivity of HIV‐1 to host restriction factors. Nat Med 2003;9:1138–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bouchard MJ, Puro RJ, Wang L, Schneider RJ. Activation and inhibition of cellular calcium and tyrosine kinase signaling pathways identify targets of the HBx protein involved in hepatitis B virus replication. J Virol 2003;77:7713–7719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Xia WL, Shen Y, Zheng SS. Inhibitory effect of cyclosporine A on hepatitis B virus replication in vitro and its possible mechanisms. Hepatobil Pancreat Dis Int 2005;4:18–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Coffin CS, Terrault NA. Management of hepatitis B in liver transplant recipients. J Viral Hepat 2007;14(Suppl 1):37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fox AN, Terrault NA. The option of HBIG‐free prophylaxis against recurrent HBV. J Hepatol 2012;56:1189–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information