Abstract

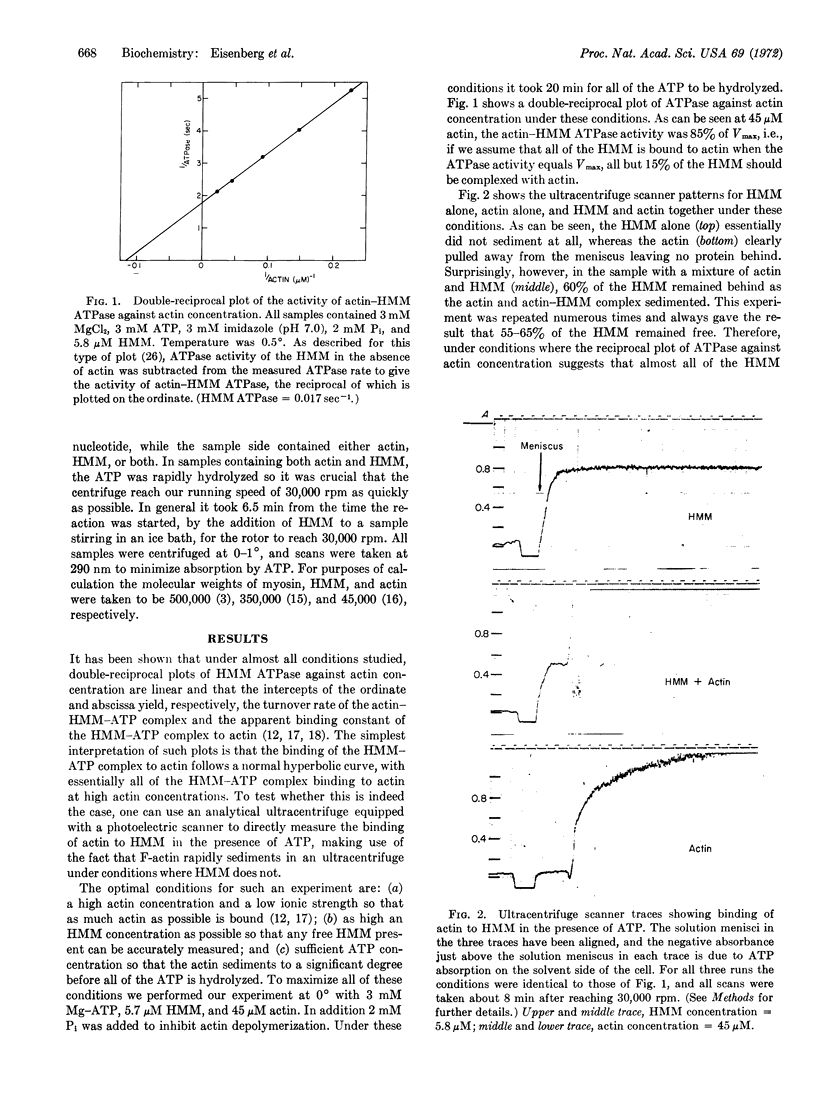

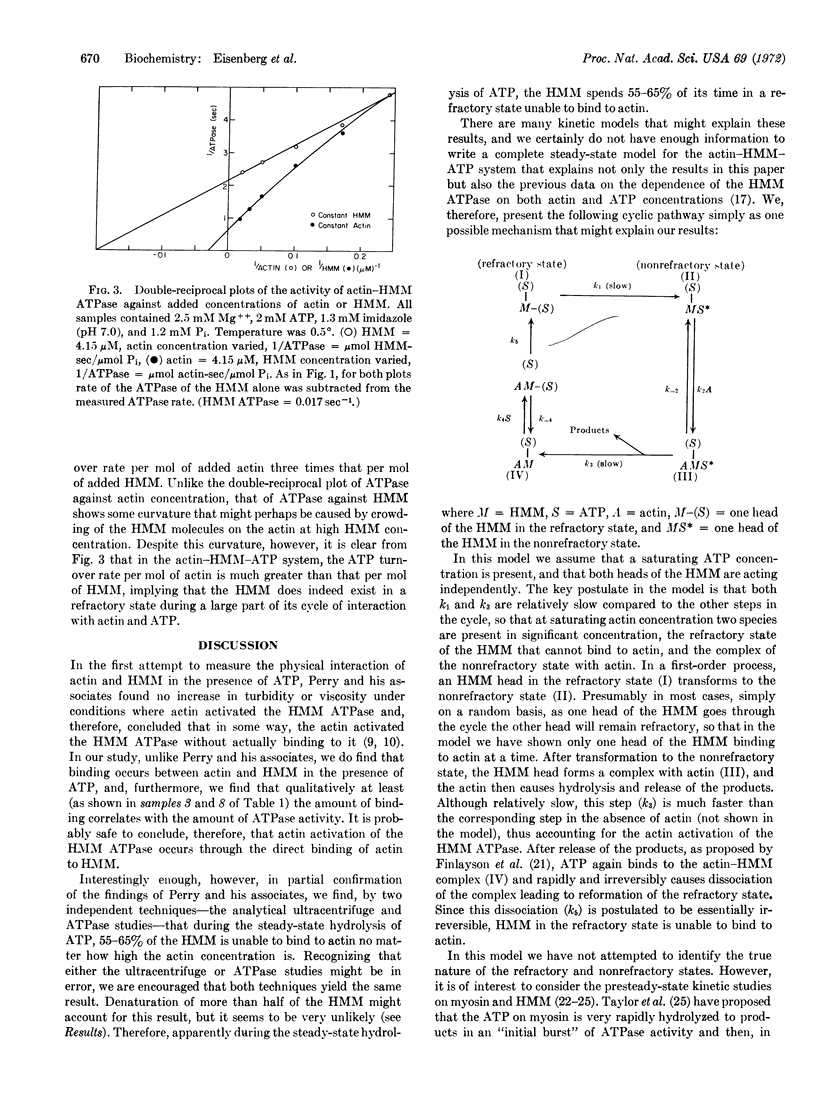

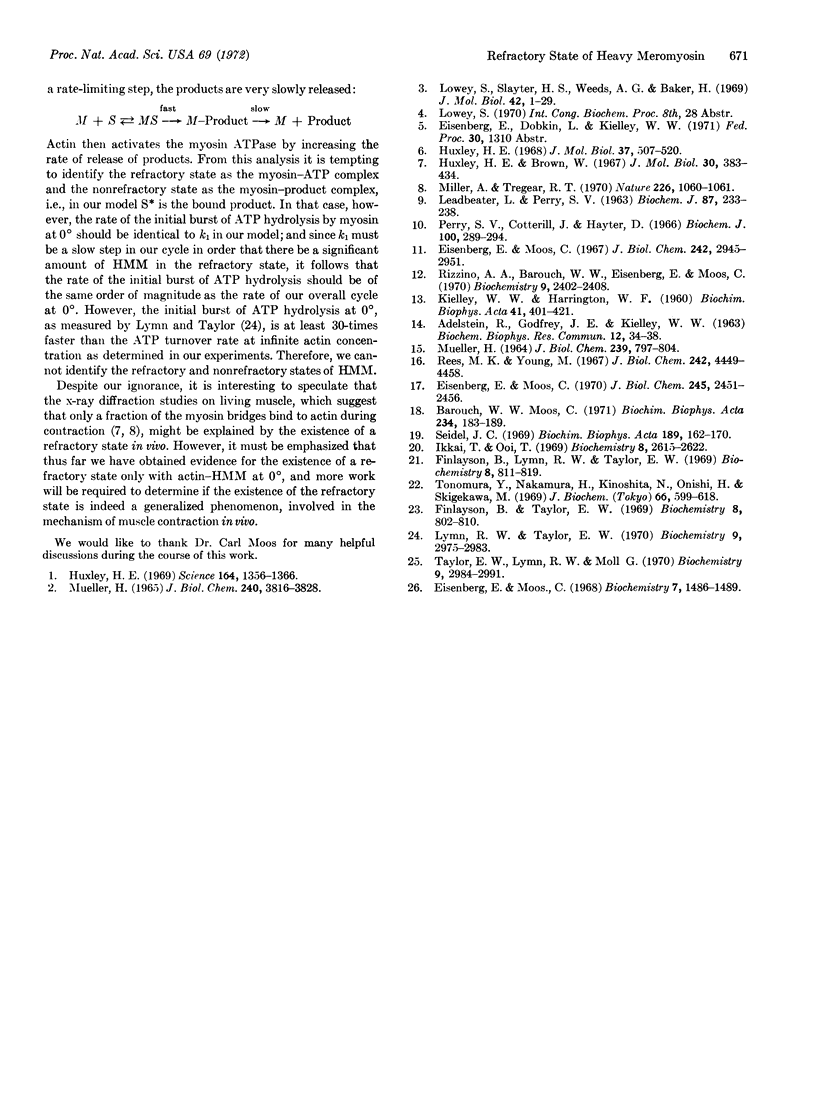

The binding of actin to heavy meromyosin (HMM) in the presence of ATP was studied by analytical ultracentrifuge and ATPase studies. At 0°C, at very low ionic strength, the double-reciprocal plot of HMM ATPase against actin concentration is linear. If one assumes that all of the HMM is bound to actin when the ATPase activity equals Vmax, then, at an actin concentration where the actin-HMM ATPase is 85% of Vmax, all but 15% of the HMM should be complexed with actin. However, when the binding of HMM to actin in the presence of ATP was measured with the analytical ultracentrifuge, more than 60% of the HMM was not bound to actin. From experiments with EDTA- and Ca-ATPases it seemed unlikely that the unbound HMM was denatured. It is thus possible that during the steady-state hydrolysis of ATP, HMM spends more than 50% of its cycle of interaction with actin and ATP in a “refractory state,” unable to bind to actin, i.e., while an HMM molecule goes through one cycle of interaction with actin and ATP, an actin monomer could bind and release several HMM molecules so that the turnover rate per mole of added actin would be considerably greater than that per mole of added HMM. Comparison of the rate of ATPase activity at very high actin concentration with that at very high HMM concentration shows that this is indeed so. Therefore, both kinetic and ultracentrifuge studies suggest that the HMM exists in a refractory state during a large part of its cycle of interaction with actin and ATP.

Keywords: muscle, myosin, enzyme kinetics

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- ADELSTEIN R. S., GODFREY J. E., KIELLEY W. W. G-actin:preparation by gel filtration and evidence for a double stranded structure. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1963 Jul 10;12:34–38. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(63)90409-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barouch W. W., Moos C. Effect of temperature on actin activation of heavy meromyosin ATPase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1971 May 11;234(2):183–189. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(71)90073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg E., Moos C. Actin activation of heavy meromyosin adenosine triphosphatase. Dependence on adenosine triphosphate and actin concentrations. J Biol Chem. 1970 May 10;245(9):2451–2456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg E., Moos C. The adenosine triphosphatase activity of acto-heavy meromyosin. A kinetic analysis of actin activation. Biochemistry. 1968 Apr;7(4):1486–1489. doi: 10.1021/bi00844a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg E., Moos C. The interaction of actin with myosin and heavy meromyosin in solution at low ionic strength. J Biol Chem. 1967 Jun 25;242(12):2945–2951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlayson B., Lymn R. W., Taylor E. W. Studies on the kinetics of formation and dissociation of the actomyosin complex. Biochemistry. 1969 Mar;8(3):811–819. doi: 10.1021/bi00831a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlayson B., Taylor E. W. Hydrolysis of nucleoside triphosphates by myosin during the transient state. Biochemistry. 1969 Mar;8(3):802–810. doi: 10.1021/bi00831a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley H. E., Brown W. The low-angle x-ray diagram of vertebrate striated muscle and its behaviour during contraction and rigor. J Mol Biol. 1967 Dec 14;30(2):383–434. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(67)80046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley H. E. Structural difference between resting and rigor muscle; evidence from intensity changes in the lowangle equatorial x-ray diagram. J Mol Biol. 1968 Nov 14;37(3):507–520. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley H. E. The mechanism of muscular contraction. Science. 1969 Jun 20;164(3886):1356–1365. doi: 10.1126/science.164.3886.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikkai T., Ooi T. The effects of pressure on actomyosin systems. Biochemistry. 1969 Jun;8(6):2615–2622. doi: 10.1021/bi00834a054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIELLEY W. W., HARRINGTON W. F. A model for the myosin molecule. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1960 Jul 15;41:401–421. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(60)90037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEADBEATER L., PERRY S. V. The effect of actin on the magnesium-activated adenosine triphosphatase of heavy meromyosin. Biochem J. 1963 May;87:233–239. doi: 10.1042/bj0870233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowey S., Slayter H. S., Weeds A. G., Baker H. Substructure of the myosin molecule. I. Subfragments of myosin by enzymic degradation. J Mol Biol. 1969 May 28;42(1):1–29. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90483-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lymn R. W., Taylor E. W. Transient state phosphate production in the hydrolysis of nucleoside triphosphates by myosin. Biochemistry. 1970 Jul 21;9(15):2975–2983. doi: 10.1021/bi00817a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MUELLER H. MOLECULAR WEIGHT OF MYOSIN AND MEROMYOSINS BY ARCHIBALD EXPERIMENTS PERFORMED WITH INCREASING SPEED OF ROTATIONS. J Biol Chem. 1964 Mar;239:797–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A., Tregear R. T. Evidence concerning crossbridge attachment during muscle contraction. Nature. 1970 Jun 13;226(5250):1060–1061. doi: 10.1038/2261060a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller H. Characterization of the molecular region containing the active sites of myosin. J Biol Chem. 1965 Oct;240(10):3816–3828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry S. V., Cotterill J., Hayter D. The adenosine-triphosphatase activity of dissociated acto-heavy-meromyosin. Biochem J. 1966 Aug;100(2):289–294. doi: 10.1042/bj1000289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees M. K., Young M. Studies on the isolation and molecular properties of homogeneous globular actin. Evidence for a single polypeptide chain structure. J Biol Chem. 1967 Oct 10;242(19):4449–4458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzino A. A., Barouch W. W., Eisenberg E., Moos C. Actin-heavy meromyosin biding. Determination of binding stoichiometry from adenosine triphosphatase kinetic measurements. Biochemistry. 1970 Jun 9;9(12):2402–2408. doi: 10.1021/bi00814a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidel J. C. The effects of monovalent and divalent cations on the ATPase activity of myosin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1969 Oct 21;189(2):162–170. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(69)90044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor E. W., Lymn R. W., Moll G. Myosin-product complex and its effect on the steady-state rate of nucleoside triphosphate hydrolysis. Biochemistry. 1970 Jul 21;9(15):2984–2991. doi: 10.1021/bi00817a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonomura Y., Nakamura H., Kinoshita N., Onishi H., Shigekawa M. The pre-steady state of the myosin-adenosine triphosphate system. X. The reaction mechanism of the myosin-ATP system and a molecular mechanism of muscle contraction. J Biochem. 1969 Nov;66(5):599–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]