Abstract

For the first time, a general catalytic procedure for the cross coupling of primary amides and alkylboronic acids is demonstrated. The key to the success of this reaction was the identification of a mild base (NaOSiMe3) and oxidant (di-tert-butyl peroxide) to promote the copper-catalyzed reaction in high yield. This transformation provides a facile, high-yielding method for the mono-alkylation of amides.

Over the past two decades, the preparation of nitrogen-containing molecules has been revolutionized by the advent of transition metal-catalyzed cross-coupling procedures for constructing Csp2-N bonds. Both aryl halide/amine cross couplings (palladium- and nickel-catalyzed Buchwald-Hartwig1 and copper-catalyzed Ullmann-type couplings2), as well as arylboronic acid/amine cross couplings (copper-catalyzed Lam-Chan reactions)3,4,5 are used to an extraordinary extent in preparing biologically active compounds and pharmaceutical agents. In contrast to these methods, the development of transition metal-catalyzed Csp3-N bond construction has lagged significantly behind. The difficulty in developing alkyl C-N bond forming reactions stems from the lack of reactivity of alkyl halides and alkylboronic acids with transition metal catalysts, as well as the propensity of intermediate alkylmetal complexes to undergo competitive β-hydride elimination (eq 1).6

Traditionally, the conversion of alkyl boronates to alkylamines has been a challenging process requiring highly electrophilic boronate reagents and electrophilic nitrogen sources.7,8 An alkyl variant of the Lam-Chan protocol has been recognized as a potential solution to this long-standing problem.4b To date, however, only a handful of alkyl Lam-Chan reactions involving alkyl boronates have been reported,9 and most are limited to the use of methyl or cyclopropylboronates.9a-d Notably, both of these substrate classes lack hydrogen atoms suitable for β-elimination.10 Additionally, most of these protocols require stoichiometric or super-stoichiometric copper promoters.9a,9b Only a single report of a catalytic reaction has been described, and the yields are often inferior compared to reactions employing stoichiometric copper.9c The Cruces group has recently reported a series of more general protocols for alkylation of anilines using a range of alkylboronic acids. These procedures require a large excess of both copper and boronic acid (up to 4 equiv each).9e,9f The large excess of alkylboronic acid required in these reactions may be consistent with partial degradation of the starting material via β-elimination pathways.11

Our interest in developing catalytic alkyl carbon-nitrogen bond-forming reactions has led us to explore the cross-coupling of primary amides with alkylboronic acids to provide secondary amides selectively. Secondary amides are important functional groups in organic chemistry, as they comprise the backbones of all natural peptides and proteins, and are widely found in therapeutic small molecules and synthetic intermediates.12 Further, although secondary amides can readily be prepared by acylation of a primary amine, the complementary mono-alkylation of a primary amide with an alkyl halide remains a difficult reaction to control and often provides modest selectivity with respect to over-alkylation (eq 2).13

Herein, for the first time, we report a general protocol for the copper-catalyzed mono-alkylation of primary amides using alkylboronic acids. The key to this reaction is the discovery that combination of a mild base (sodium trimethylsilanolate, NaOSiMe3, pka’ = 12.7)14 and di-tert-butyl peroxide (DTBP) as the oxidant is uniquely effective in promoting the catalytic cross-coupling reaction of primary amides and primary boronic acids.11 This reaction is completely tolerant of β-hydrogen atoms, and, in most cases, requires only a small excess of alkylboronic acid. This protocol offers a simple method for preparing secondary amides, while providing a rare example of catalytic alkyl C–N cross-coupling.8a,9c,15

We began by examining the reaction of benzamide and iso-butylboronic acid (Table 1). Under typical Lam-Chan reaction conditions, employing Cu(OAc)2 as catalyst and air (or dry oxygen) as the oxidant with a mild base, only traces of the desired secondary amide 1 were observed (entries 1 and 2). The use of ligand additives, such as 2,2′-bipyridine, did not positively affect the reaction (not shown). In contrast, the use of stoichiometric Cu(OAc)2 (4 equiv) under air did lead to a small, but measurable increase in the yield of the product (up to 5% as determined by NMR, not shown). We suspected that this result might indicate ineffective catalyst turnover. Accordingly, we examined the role of the oxidant in the reactions conducted under a nitrogen atmosphere. Whereas a range of common oxidants such as (diacetoxyiodo)benzene, benzoquinone, hydrogen peroxide, meta-chloroperbenzoic acid, and tert-butyl hydrogen peroxide (entries 3-7) were completely ineffective, the use of di-tert-butyl peroxide (DTBP, entry 8) provided discernibly more product under catalytic conditions. A stronger base (NaOtBu, entry 9) and optimization of the solvent to tBuOH (entry 10) provided further increases in the yield.16 Interestingly, with the use of tBuOH as solvent, the use of NaOSiMe3 provided a significant increase in yield (87%, entry 15). With this weaker base, the equilibrium concentration of deprotonated amide is expected to be lower, which we suspect might prevent competitive ligation of the copper catalyst. Finally, we elected to examine the use of other copper salts as precatalysts; CuBr proved to be slightly more effective, leading to a 92% assay yield under optimized conditions.17 The reaction is completely selective for mono alkylation; in no case was any dialkylated product detected.

Table 1.

Identification of Reaction Conditions.

| entry | catalyst | base | oxidant | solvent | yielda |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cu(OAc)2 | Na2CO3 | air | DCE | trace |

| 2 | Cu(OAc)2 | Na2CO3 | O2 | DCE | trace |

| 3 | Cu(OAc)2 | Na2CO3 | PhI(OAc)2 | DCE | 0% |

| 4 | Cu(OAc)2 | Na2CO3 | BQ | DCE | 0% |

| 5 | Cu(OAc)2 | Na2CO3 | H2O2 | DCE | 0% |

| 6 | Cu(OAc)2 | Na2CO3 | m-CPBA | DCE | 0% |

| 7 | Cu(OAc)2 | Na2CO3 | TBHP | DCE | 0% |

| 8 | Cu(OAc)2 | Na2CO3 | DTBP | DCE | 5% |

| 9 | Cu(OAc)2 | NatOBu | DTBP | DCE | 31% |

| 10 | Cu(OAc)2 | NatOBu | DTBP | tBuOH | 36% |

| 11 | Cu(OAc)2 | NaOSiMe3 | DTBP | tBuOH | 87% |

| 12 | Cu(OAc) | NaOSiMe3 | DTBP | tBuOH | 71% |

| 13 | CuCl | NaOSiMe3 | DTBP | tBuOH | 70% |

| 14 | CuI | NaOSiMe3 | DTBP | tBuOH | 88% |

| 15 | CuBr | NaOSiMe3 | DTBP | tBuOH | 92% |

Yield determined using NMR. DCE = 1,2-dichloroethane; BQ = Benzoquinone; m-CPBA = meta-chloroperbenzoic acid; TBHP = tert-butyl hydrogen peroxide; DTBP = di-tert-butyl peroxide.

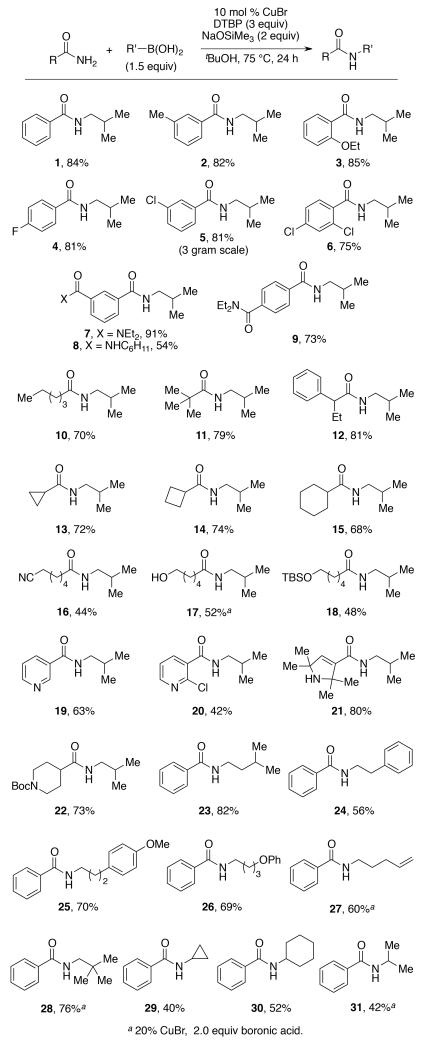

Under preparative conditions, amide 1 was isolated in 84% yield (1 mmol scale, Scheme 1).18 Significantly, the reaction conditions developed for this substrate proved highly general with respect to both amide and alkylboronic acid. As shown in Scheme 1, a variety of substituents on the amide were well tolerated, including alkyl groups (2), aromatic ethers (3), tertiary amides (7 and 9), as well as alkyl nitriles (16), alcohols (17), and silyl ethers (18). As expected from the high selectivity for mono-alkylation, secondary amides were inert under the alkylation conditions (8). Electron-rich (3), as well as mildly electron-deficient (4 and 9), amides were highly effective substrates. However, benzamides bearing electron-withdrawing groups stronger than p-dialkylamides failed to react. While aryl fluorides (4) and chlorides (5 and 6) were well tolerated, we found that reactions involving aromatic bromides were less effective, providing only low yields of the desired product. Unfortunately, esters (both aromatic and alkyl) proved incompatible with the reaction conditions due to competitive hydrolysis.19 In contrast, aliphatic amides were excellent substrates for the reaction. This includes linear amides such as hexanoamide (10), as well as those containing branching alpha to the carbonyl, such as in 11 and benzylic amide 12. Amides containing carbocyclic rings were also were well tolerated, including those containing cyclopropyl, cyclobutyl, and cyclohexyl units (13-15). Significantly, heterocyclic amides were also suitable substrates in the reaction. This includes both heteroaromatic compounds, such as those leading to 19 and 20, as well as non-aromatic heterocycles (21 and 22). The latter two examples demonstrate that both protic and protected amines can also be tolerated in the reaction. Finally, the reaction also proved to be highly scalable; amide 5 was prepared on a 3-gram scale (ca. 20 mmol) in 81% yield, which was nearly identical to that obtained on a 1-mmol scale.

Scheme 1.

Substrate Scope for Amide Alkylation.

The copper-catalyzed alkylation reaction is not limited to the use of iso-butylboronic acid. As demonstrated by the preparation of amides 23-31, a wide range of boronic acids can be utilized as alkylating reagents. This includes those bearing functional groups, such as arenes, ethers and alkenes (24-27), as well as more sterically demanding primary alkylboronic acids, such as neopentylboronic acid (28). Taken together with the examples above, the coupling reaction displays wide functional group tolerance.

Finally, we have examined the scope with respect to more substituted boronic acids. Whereas tertiary boronic acids (such as tert-butylboronic acid, not shown) were not successful substrates for the cross-coupling reaction, some secondary boronic acids did undergo coupling. For example, cyclopropyl- and cyclohexylboronic acids both underwent coupling, giving rise to 29 and 30 in modest yield. However, other similar secondary boronic acids were less successful. For example, the use of isopropylboronic acid required excess reagent and catalyst to afford a modest yield. We believe that this difference in yield corresponds to low stability of isopropylboronic acid relative to the others.

In conclusion, we have developed a mild, inexpensive, functional group tolerant method for the synthesis of secondary amides via the cross coupling of primary amides with alkylboronic acids. We demonstrated that the Lam-Chan-type reaction can be carried out efficiently using a catalytic amount of copper, and for the first time,11 DTBP was discovered as an effective oxidant for the process. Moreover, the application of alkylboronic acids in the cross coupling significantly broadens the scope of Lam-Chan-type reactions in organic synthesis. Further efforts will be directed toward investigation of the detailed reaction mechanism20 and expansion of the generality of the transformation.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Strategies for Monoalkylation of Primary Amides

Acknowledgment

The University of Delaware (UD) and the ACS Petroleum Research Fund (51706-DNI1) are gratefully acknowledged for funding and other research support. NMR and other data were acquired at UD on instruments obtained with the assistance of NSF and NIH funding (NSF MIR CHE0421224 and CHE1229234, NSF CRIF MU CHE0840401, NIH P20 GM103541, NIH S10 RR02692).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available Experimental procedures and spectral data for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- (1).(a) Surry D, Buchwald S. Chem. Sci. 2011;2:27–50. doi: 10.1039/C0SC00331J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hartwig J. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:1534–1544. doi: 10.1021/ar800098p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Surry DS, Buchwald SL. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:6338–6361. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Monnier F, Taillefer M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:6954–6971. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).(a) Chan DMT, Monaco KL, Wang R-P, Winters MP. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:2933–2936. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lam PYS, Clark CG, Saubern S, Adams J, Winters MP, Chan DMT, Combs A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:2941–2944. [Google Scholar]

- (4).For recent reviews, see: Sanjeeva Rao K, Wu T-S. Tetrahedron. 2012;68:7735–7754. Qiao J, Lam P. Synthesis. 2011;2011:829–856. Chan DMTL, P.Y.S. In: Boronic Acids. Hall DG, editor. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2005. pp. 205–240. Ley SV, Thomas AW. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003;42:5400–5449. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300594.

- (5).For a related reaction involving Ar-O bond formation, see: Evans DA, Katz JL, West TR. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:2937–2940.

- (6).A number of C-C cross coupling reactions involving alkyl reagents have been developed. For a recent review, see: Jana R, Pathak TP, Sigman MS. Chem. Rev. 2013;111:1417–1492. doi: 10.1021/cr100327p.

- (7).(a) Brown HC, Heydkamp WR, Breuer E, Murphy WS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964;86:3565–3566. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kabalka GW, Sastry KAR, McCollum GW, Yoshioka H. J. Org. Chem. 1981;46:4296–4298. [Google Scholar]; (c) Brown HC, Kim KW, Srebnik M, Bakthan S. Tetrahedron. 1987;43:4071–4078. [Google Scholar]; (d) Matteson DS, Kim GY. Org. Lett. 2002;4:2153–2155. doi: 10.1021/ol025973d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).For recent advances in this area, see: Rucker RP, Whittaker AM, Dang H, Lalic G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:6571–6574. doi: 10.1021/ja3023829. Mlynarski SN, Karns AS, Morken JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:16449–16451. doi: 10.1021/ja305448w.

- (9).(a) Benard S, Neuville L, Zhu J. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:3393–3395. doi: 10.1039/b925499d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bénard S. b., Neuville L, Zhu J. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:6441–6444. doi: 10.1021/jo801033y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Tsuritani T, Strotman NA, Yamamoto Y, Kawasaki M, Yasuda N, Mase T. Org. Lett. 2008;10:1653–1655. doi: 10.1021/ol800376f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) González I, Mosquera J, Guerrero C, Rodríguez R, Cruces J. Org. Lett. 2009;11:1677–1680. doi: 10.1021/ol802882k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Larrosa M, Guerrero C, Rodríguez R, Cruces J. Synlett. 2010;2010:2101–2105. [Google Scholar]; (f) Naya L, Larrosa M, Rodríguez R, Cruces J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012;53:769–772. [Google Scholar]

- (10).β-Hydride elimination from metal cyclopropanes has been shown to be a highly unfavorable process. See: Nuzzo RG, Mccarthy TJ, Whitesides GM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981;103:3404–3410.

- (11).During the preparation of this manuscipt, a report describing the catalytic alkylation of anilines using similar reaction conditions to ours was published in this journal, see: Sueki S, Kuninobu Y. Org. Lett. 2013;15:1544–1547. doi: 10.1021/ol400323z.

- (12).(a) Zabicky J. Amides. Wiley; Weinheim: 1970. [Google Scholar]; (b) Stanley M, Rotrosen J. The Benzamides: Pharmacology, Neurobiology, and Clinical Aspects. Raven Press; New York: 1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wieland T, Bodanszky M. The World of Peptides: a Brief History of Peptide Chemistry. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 1991. [Google Scholar]; (d) Hecht SM, editor. Bioorganic Chemistry: Peptides and Proteins. Oxford University Press; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]; (e) Greenberg A, Breneman CM, Liebman JF. The Amide Linkage: Structural Significance in Chemistry, Biochemistry, and Materials Science. Wiley; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]; (f) Sinning C, Watzer B, De Petrocellis L, Di Marzo V, Imming P. ChemMedChem. 2008;3:1956–1964. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200800271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) McGrath NA, Brichacek M, Njardarson JT. J. Chem. Ed. 2010;87:1348–1349. [Google Scholar]; (h) Pattabiraman VR, Bode JW. Nature. 2011;480:471–479. doi: 10.1038/nature10702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Watanabe Y, Ohta T, Tsuji Y. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1983;56:2647–2651. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Blaschette A, Bressel B. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. Lett. 1968;4:175–178. [Google Scholar]

- (15).(a) Berman A, Johnson J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:5680–5681. doi: 10.1021/ja049474e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Campbell M, Johnson J. Org. Lett. 2007;9:1521–1524. doi: 10.1021/ol0702829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Matsuda N, Hirano K, Satoh T, Miura M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:11827–11831. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Other solvents were also examined in this reaction, see Supporting Information for details.

- (17).Further attempts to optimize the reaction (varied temperature, time, concentration and equivalents of reagents) lead to lower yields of 1.

- (18).All reported isolated yields are the average of at least two runs.

- (19).The incompatibility of ester under the reaction conditions appears to be due to the combination of the mildly basic conditions with the Lewis acidic catalyst. Control experiments showed that esters decomposed only when base and catalyst were present.

- (20).For mechanistic studies on aryl Lam-Chan reactions, see: King AE, Brunold TC, Stahl SS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:5044–5045. doi: 10.1021/ja9006657.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.