Abstract

Nucleic acid modulation by small molecules is an essential process across the kingdoms of life. Targeting nucleic acids with small molecules represents a significant challenge at the forefront of chemical biology. Nucleic acid junctions are ubiquitous structural motifs in nature and in designed materials. Herein, we describe a new class of structure specific nucleic acid junction stabilizers based on a triptycene scaffold. Triptycenes provide significant stabilization of DNA and RNA three-way junctions, providing a new scaffold for building nucleic acid junction binders with enhanced recognition properties. Additionally, we report cytotoxicity and cell uptake data in two human ovarian carcinoma cell lines.

Keywords: DNA recognition, RNA recognition, Triptycene, three-way junctions, antitumor agents, nucleic acid recognition, molecular recognition

Nucleic acid junctions are ubiquitous structural motifs, occurring in both DNA and RNA.[1] Three-way junctions have been extensively studied by many biophysical techniques[2] and represent important and sometimes transient structures in biological processes, such as replication and recombination,[3] while also occuring in triplet repeat expansions, which are associated with a number of neurodegenerative diseases.[4] Nucleic acid junctions are ubiquitous in viral genomes and are important structural motifs in riboswitches where small molecule modulation holds great potential.[5] Three-way junctions are key building blocks present in many nanostructures,[6] soft materials,[7] multichromophore assemblies,[8] and aptamer-based sensors.[9] In the case of aptamer based sensors, DNA three-way junctions serve as an important structural motif. The ability to modulate aptamers using specific small molecules represents an important challenge for designing nucleic acid sensors, switches and devices.[9]

Pioneering discoveries by Hannon, Coll and co-workers have demonstrated that metal helicates can bind nucleic acid junctions in addition to quadruplexes and helical motifs.[10] Inspiring structural studies have yielded high-resolution details of nucleic acid junctions complexed with proteins and metal helicates, providing a starting point for rational structure-based design efforts.[3b, 10b, 10g] Given the ubiquity of nucleic acid junctions and the potential for many diverse applications, a better understanding of junction molecular recognition is needed in addition to an expanded toolbox of small molecule probes. Despite the vast number of important nucleic acid targets, we still lack the ability to selectively modulate predetermined nucleic acid structures using small molecules with high specificity and affinity beyond a few well-established recognition modes such as groove binding.[11] Small molecule targeting of non-canonical nucleic acid motifs and higher-order structures represent an important challenge at the forefront of chemistry and chemical biology.[12]

Herein, we report a new structure selective triptycene-based scaffold for targeting nucleic acid junctions. UV-Vis, circular dichroism (CD), gel shift, and fluorescence quenching experiments were used to assess junction recognition properties. We find that triptycene-based junction binders exhibit a significant stabilization of perfectly paired DNA and RNA three-way junctions.[13] Further, we report initial cytotoxicity and cell uptake data compared to cisplatin, in two human ovarian carcinoma cell lines.

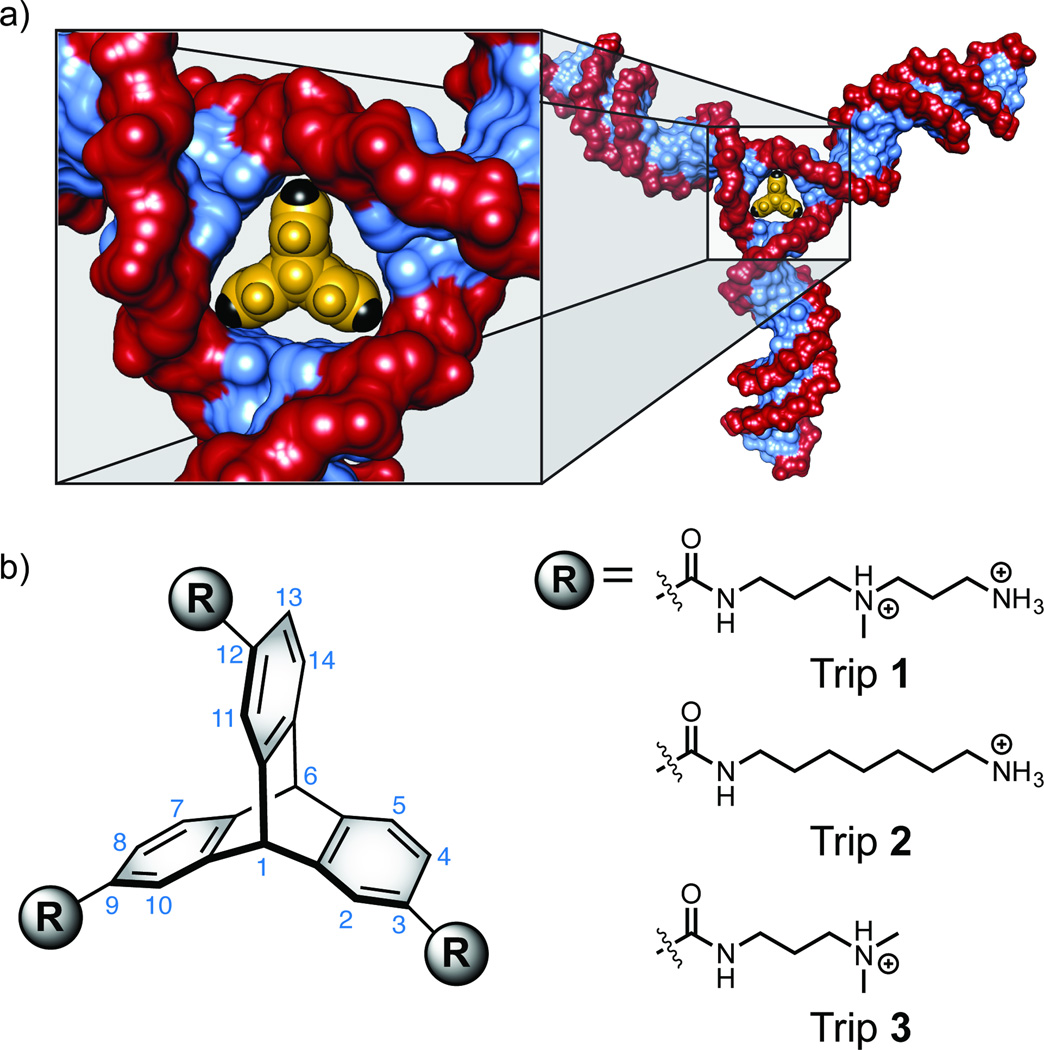

Our molecular design began with the recognition that triptycene[14] possessed a 3-fold symmetric architecture with dimensions similar to those of the central helical interface of a perfectly base-paired nucleic acid three-way junction.[3b, 10b, 10g] Despite the occurrence of triptycene in materials applications,[15] there is a paucity of examples where it has successfully been used for biomolecular recognition.[16] From our analysis of the three-way junction binding site dimensions, we envisioned that the trigonal symmetry and non-planar π-surface of the aromatic rings in triptycene could potentially form stacking or buckled base pair interactions with nucleobases at the junction interface, allowing for a shape selective fit.[3b, 10b, 10g, 17] The choice of a non-intercalative scaffold to minimize non-specific nucleic acid binding was important to our design, and the triptycene structure satisfied this requirement. In previous studies, we have demonstrated that the introduction of geometric and macrocyclic constraints in nucleic acid binding small molecules can be used as a strategy to lock out common binding modes such as intercalation and groove binding.[18] Recently, we reported that dimeric azaxanthone (diazaxanthylidene) structures lack the ability to bind B-form DNA due to their preference for an anti-folded conformation, despite the DNA binding ability of well-known monomeric xanthone intercalators.[18b] In our previous studies we attributed the lack of B-form DNA binding to the discontinuous pi-system, caused by the overcrowded anti-folded molecular architecture.[18b] This hypothesis is consistent with the architectural requirements for classical intercalator scaffolds, requiring more than one ring of continuous planar π-surface area.[19] By a similar structural analysis, we expected the discontinuous π-surface area of triptycene to rule out classical intercalative binding modes. In addition to the shape complementarity and three-dimensional architecture of the triptycene scaffold, we were attracted to its modularity and potential for diversity. The triptycene scaffold provides up to 14 positions for diversification, three rings with four positions each in addition to two bridgehead positions. Triptycene can also be thought of as having three buckled π-faces and two three-fold symmetric edge faces with a bridgehead located at the center of each. These structural attributes of triptycene will become important for future studies as we consider topological differentiation of nucleic acid junction faces for achieving sequence specificity and distinguishing DNA from RNA junctions. Size comparison of the triptycene core relative to previously reported DNA and RNA three-way junction crystal structures[3b, 10b, 10g] confirmed our initial hypothesis regarding triptycene shape complementarity, prompting us to initiate synthetic efforts toward the first rationally designed nucleic acid junction binders based on triptycene (Figure 1a). We synthesized triptycenes 1–3 (Trip 1–3) and evaluated their ability to discriminate a DNA 3WJ from dsDNA, using well-established UV and CD spectroscopic techniques (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Triptycene scaffold for nucleic acid three-way junction targeting. (a) Relative size comparison of triptycene bound to the putative DNA 3WJ binding pocket. Model complex based on a crystal structure of trimeric Cre recombinase bound to a three-way Lox DNA junction (PDB ID: 1F44). [3b] (b) Structure of triptycene derivatives (Trip 1–3) utilized for targeting nucleic acid junctions.

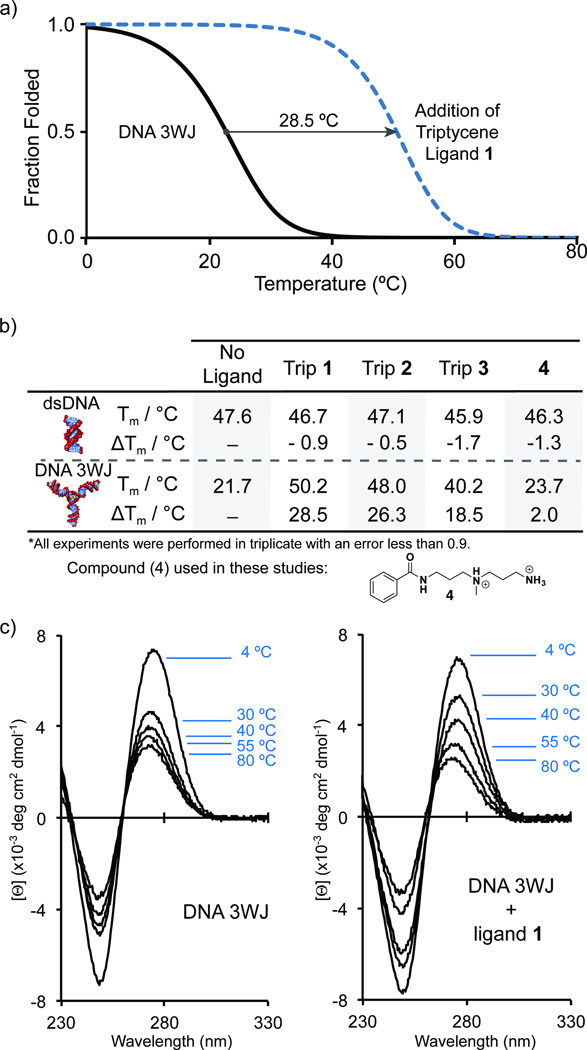

Figure 2.

Thermal stabilization data. (a) Representative fraction folded plot derived from UV thermal melting experiments showing significant stabilization in the presence of triptycene 1. Plot was derived using standard fitting procedures. (b) Table of UV thermal stabilization data comparing dsDNA and DNA 3WJ. Compound 4 was used to demonstrate the unique ability of triptycene to act as a structure specific core. Hairpin DNA showed no significant stabilization in the presence of ligands. (c) Circular dichroism spectra of DNA 3WJ in the absence (left) and presence (right) of triptycene 1. (Sequences of oligonucleotides used in these studies are as follows: DNA 3WJ: 5’-CGA CAA AAT GCA AAA GCA TTA CTT CAA AAG AAG TTT GTC G-3’, dsDNA: 5’-CCAGTACTGG-3’, Hairpin DNA: 5’-CAA AAT GCA AAA GCA TTT TG-3’.)

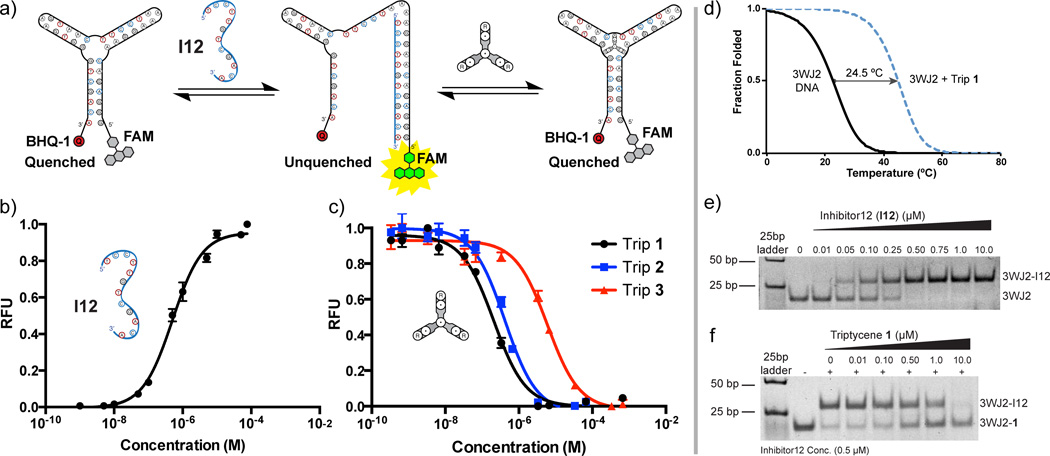

UV thermal melting experiments were performed to determine the degree of stabilization of Trip 1–3 toward a DNA 3WJ versus dsDNA (Figure 2a,b). Triptycenes 1–3 did not stabilize dsDNA even though a significant stabilization of the DNA 3WJ was observed, with ΔTm values of 28.5, 26.3, and 18.5 °C for Trip 1–3, respectively (Figure 2b). Maximum stabilization was achieved after addition of slightly more than one equivalent of ligand (Figure S4). Triptycene derivatives 1–3 also provide a comparison of the effect of positive charge and linker length on junction stabilization. Triptycenes 2 and 3, where the internal and terminal amines have been removed, demonstrate that the linker length is an important structural parameter to explore in future studies. Despite the decreased number of charges in Trip 2 and 3, both compounds retain significant 3WJ stabilizing ability (Figure 2b). As a further control experiment, stabilization of a DNA hairpin corresponding to one of the arms of the junction was evaluated and showed no significant stabilization (Figure S8). To further study the impact of the triptycene core, compound 4 was synthesized. Compound 4 consists of the minimal repeating structural motif embedded in the trimeric architecture of triptycenes 1–3. UV melting analysis with 4 results in a ΔTm = 2.0 °C for DNA 3WJ and a ΔTm = −1.3 °C for dsDNA (Figure 2b). This lack of stabilization further demonstrates the unique structure selectivity imparted by triptycenes 1–3. Trip 1 was also evaluated against a well studied three-way junction (3WJ2) shown in Figure 3.[9c] The stability of this junction was found to increase by 24.5 °C in the presence of Trip 1. In addition to DNA three-way junction stabilization studies, we have conducted initial studies with RNA three-way junctions. Triptycenes 1–3 stabilize RNA three-way junctions by UV melting analysis. The ΔTm values for stabilization of the RNA 3WJ are as follows: Trip 1 = 12.5 °C, Trip 2 = 2.9 °C, and Trip 3 = 3.4 °C (Figure S13). Development of RNA selective junction binders is underway and will be reported in due course.

Figure 3.

Fluorescence quench assay, thermal stability data, and gel shift data. (a) Schematic of the fluorescence quench based competitive oligonucleotide inhibition assay. (b) Opening the three-way junction (3WJ2) with a complementary oligonucleotide (I12). Fluorescence increases with an increase in concentration of I12. (c) Closing of the three-way junction (3WJ2) and displacement of competitive inhibitor I12 with triptycenes 1, 2, and 3. Fluorescence decreases with an increase in concentration of triptycene. The observed Kd’s for Trip 1, 2, and 3 were determined to be 0.221 µM, 0.396 µM, and 5.50 µM, respectively. (d) Fraction folded plot derived from UV thermal melting experiments showing significant stabilization in the presence of triptycene 1. (e) Gel shift data showing opening of the three-way junction DNA using a complementary oligonucleotide analogous to the fluorescence quench in 3b. (f) Displacement of the complementary oligonucleotide and reformation of the three-way junction upon titration of triptycene 1. (Sequences of oligonucleotides used in these studies are as follows: DNA 3WJ2: 5’-GGG AGA CAA GGA AAA TCC TTC AAT GAA GTG GGT CGA CA-3’, Inhibitor strand I12: 5’-TCC TTG TCT CCC-3’, double labeled oligo sequence matches that of 3WJ2)

Circular dichroism (CD) was used to further explore the interaction of Trip 1 with the DNA 3WJ (Figure 2c and Figure S9). The temperature-dependent CD spectra of the DNA 3WJ with and without Trip 1 exhibit a maximum at 275 nm and a minimum at 245 nm centered around 260 nm, which is indicative of the B-DNA helical conformation. This CD signature resembles that of other intramolecular nucleic acid junctions.[20] As the temperature was increased from 4 °C to 80 °C, the maximum at 275 nm decreased, and the minimum at 245 nm became less negative. The temperature-induced change in the CD spectrum indicates melting of the DNA 3WJ helical arms. The largest change in the spectrum for the DNA 3WJ was observed between 4 °C and 30 °C. In the presence of Trip 1, the CD maximum at 275 nm decreased more gradually with increasing temperature, which is consistent with the ligand-induced stabilization observed during UV experiments. A CD thermal denaturation experiment, in which the molar ellipticity is measured at 255 nm as a function of temperature, further demonstrated the dramatic stabilization of DNA 3WJ in the presence of Trip 1. The CD ΔTm was determined to be 27.4 °C, which is in agreement with the UV thermal denaturation results (Figure S10).

Gel shift experiments were performed on DNA 3WJ2 to further support junction binding by 1 (Figure 3). Addition of increasing concentrations of Trip 1 directly to DNA 3WJ2 did not result in a measurable shift using a polyacrylamide gel. This indicates that there is likely not a non-specific intercalative binding mode. To further confirm that Trip 1 binds the three-way junction, 3WJ2 was incubated with a 12 bp oligonucleotide complementary to the 5‘-end of the junction (inhibitor 12). Consistent with the known DNA three-way junctions in the literature, faster migration was observed relative to the migration of duplex DNA (<25 bp), suggesting the formation of a more compact 3WJ structure. Titration of inhibitor 12 (I12) results in a slower-migrating band on the gel, indicating the formation of a larger complex (Figure 3e). Addition of increasing concentrations of Trip 1, results in reformation of the three-way junction and displacement of the inhibitor strand (Figure 3f).

A fluorescence quenching experiment was used to verify binding to the three-way junction.[9c] The 5’- and 3’-ends of a DNA 3WJ forming oligonucleotide were labeled with a fluorophore (FAM) and a quencher (BHQ-1), respectively (Figure 3). Folding of the junction brings the 5’ and 3’ ends into close proximity resulting in fluorescence quenching. A 12 bp oligonucleotide, complementary to the 5’-end of the junction, was used as an inhibitor to stabilize the open state of the junction.[9c] Addition of Trip 1 to the unquenched state of the 3WJ2-I12 complex resulted in a decrease in fluorescence, indicating that the ends were brought into close proximity as a result of 3WJ formation. The apparent Kd of the triptycenes were determined to be 0.221 µM for Trip 1, 0.396 µM for Trip 2, and 5.50 µM for Trip 3 in the fluorescence displacement assay (Figure 3a, b).

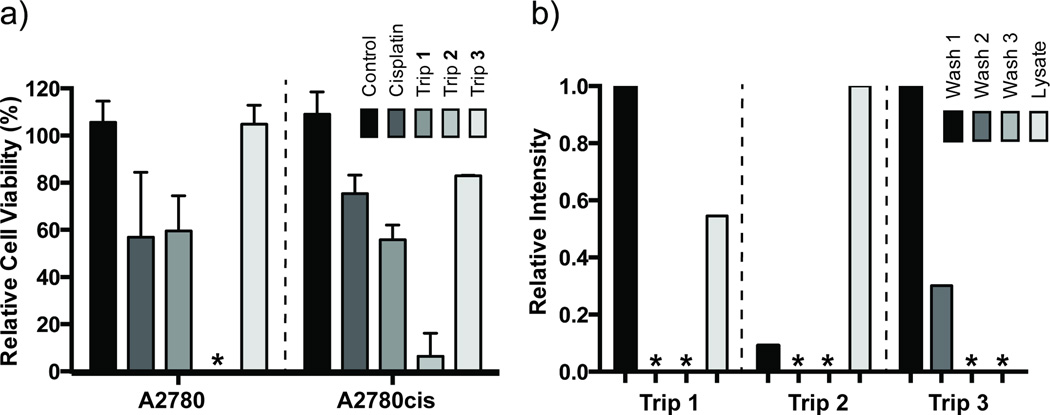

Initial studies of the cytotoxicity and cell uptake for Trip 1–3 were conducted using human ovarian carcinoma cell lines. Previous studies of metallohelicates show diverse biological activity[10a, 10f, 21] and cytotoxic effects in cisplatin resistant A2780cis cell lines. This promising result for the metallohelicates led us to explore initial cytotoxicity studies for triptycenes 1–3 in these cell lines. Their activity was investigated in human ovarian carcinoma A2780 cells and the cisplatin-resistant A2780cis cell line using an Alamar blue assay.[22] Significant differences in sensitivity were observed for each of the triptycenes in the two cell lines compared to cisplatin (Figure 4a). No cytotoxic activity was observed for triptycene 3. Triptycene 1 shows similar potency to cisplatin in the A2780 cell line, but demonstrated increased cytotoxicity against the A2780cis cell line compared to cisplatin. The highest potency was observed for triptycene 2, with a complete loss of cell viability observed for A2780 cells and only 6% viability for A2780cis cells. Triptycenes 1–3 show very promising anticancer activity, demonstrating increased or similar potency to cisplatin in the cell lines tested. We conducted cellular uptake studies in A2780 cells and demonstrate that triptycenes can be efficiently internalized within two hours post treatment. Trends in cellular uptake parallel our initial cytotoxicity data with the most potent compound Trip 2 showing the greatest cellular uptake, followed by Trip 1 and Trip 3 (Figure 4b). Further biological and structure-activity relationship studies are underway and will be reported in due course.

Figure 4.

Cytotoxicity and cell uptake studies using human ovarian carcinoma cell lines. (a) Percent viability of A2780, a cisplatin sensitive ovarian cancer cell line, and A2780cis, a cisplatin-sensitive ovarian cancer cell line, in the presence of triptycenes 1–3 or cisplatin. Viability is shown at a final concentration of 50 µM for each compound. All experiments were conducted in duplicate and the asterisk indicates zero viability. (b) Cell uptake studies using MALDI-MS for Trip 1–3 in A2780 cells. Asterisk = no detectible compound.

In summary, we have rationally designed a new class of non-intercalative triptycene-based nucleic acid junction binders. We have demonstrated that triptycene-based molecules have the ability to recognize both DNA and RNA three-way junctions, providing a new versatile scaffold for targeting higher-order nucleic acid structure. Initial biological studies show promising cytotoxicity in cisplatin resistant human ovarian carcinoma cell lines and positive cellular uptake. Ongoing efforts in our laboratory are directed toward the recognition of both DNA and RNA junctions in addition to the development of new classes of structure specific nucleic acid modulators. Junctions are one of the most ubiquitous structural motifs and many exciting opportunities exist for developing small molecule modulators of higher-order structures such as three-way and four-way junctions.[12, 23–25] Small molecule targeting of non-canonical nucleic acid motifs and higher-order structures represent an important challenge at the forefront of chemistry and chemical biology with many exciting opportunities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the University of Pennsylvania. Instruments supported by the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health including HRMS (NIH RR-023444) and MALDI-MS (NSF MRI-0820996). S.A.B. wishes to thank the NIH for funding through the Chemistry-Biology Interface Training Program (T32 GM07133). We thank Professor Ashani Weeraratna, Amanpreet Kaur, and Professor Rugang Zhang for the cell lines and advice on cell culture. We also thank the Wistar Molecular Screening Facility for assistance.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

References

- 1.a) Lilley DM. Quarterly reviews of biophysics. 2000;3:109–159. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500003590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Duckett DR, Lilley DM. The EMBO journal. 1990;9:1659–1664. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08286.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Altona C. J Mol Biol. 1996;263:568–581. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Seeman NC, Kallenbach NR. Annu Rev Bioph Biom. 1994;23:53–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.23.060194.000413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Overmars FJ, Pikkemaat JA, van den Elst H, van Boom JH, Altona C. J Mol Biol. 1996;255:702–713. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) van Buuren BN, Overmars FJ, Ippel JH, Altona C, Wijmenga SS. J Mol Biol. 2000;304:371–383. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Welch JB, Walter F, Lilley DM. J Mol Biol. 1995;251:507–519. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Muhuri S, Mimura K, Miyoshi D, Sugimoto N. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:9268–9280. doi: 10.1021/ja900744e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Sabir T, Toulmin A, Ma L, Jones AC, McGlynn P, Schroder GF, Magennis SW. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:6280–6285. doi: 10.1021/ja211802z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Zhang X, Tung CS, Sowa GZ, Hatmal MM, Haworth IS, Qin PZ. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:2644–2652. doi: 10.1021/ja2093647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Leontis NB, Piotto ME, Hills MT, Malhotra A, Ouporov IV, Nussbaum JM, Gorenstein DG. Methods in enzymology. 1995;261:183–207. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(95)61010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Lilley DM. Methods in enzymology. 2009;469:143–157. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)69007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Bailor MH, Mustoe AM, Brooks CL, 3rd, Al-Hashimi HM. Nature protocols. 2011;6:1536–1545. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Klostermeier D, Millar DP. Biochemistry-Us. 2000;39:12970–12978. doi: 10.1021/bi0014103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k) Kadrmas JL, Ravin AJ, Leontis NB. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:2212–2222. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.12.2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l) Husler PL, Klump HH. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;313:29–38. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Singleton MR, Scaife S, Wigley DB. Cell. 2001;107:79–89. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00501-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Woods KC, Martin SS, Chu VC, Baldwin EP. J Mol Biol. 2001;313:49–69. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Mirkin SM. Nature. 2007;447:932–940. doi: 10.1038/nature05977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Slean MM, Reddy K, Wu B, Nichol Edamura K, Kekis M, Nelissen FH, Aspers RL, Tessari M, Scharer OD, Wijmenga SS, Pearson CE. Biochemistry-Us. 2013;52:773–785. doi: 10.1021/bi301369b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Leonard CJ, Berns KI. Progress in nucleic acid research and molecular biology. 1994;48:29–52. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60852-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Smith KD, Lipchock SV, Ames TD, Wang J, Breaker RR, Strobel SA. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2009;16:1218–1223. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Deigan KE, Ferre-D'Amare AR. Accounts of chemical research. 2011;44:1329–1338. doi: 10.1021/ar200039b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Serganov A, Patel DJ. Annu Rev Biophys. 2012;41:343–370. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-101211-113224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Serganov A, Patel DJ. Curr Opin Struc Biol. 2012;22:279–286. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Serganov A, Nudler E. Cell. 2013;152:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Breaker RR. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2012:4. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Aldaye FA, Palmer AL, Sleiman HF. Science. 2008;321:1795–1799. doi: 10.1126/science.1154533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Shu D, Shu Y, Haque F, Abdelmawla S, Guo P. Nature nanotechnology. 2011;6:658–667. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Duprey JLHA, Takezawa Y, Shionoya M. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2013;52:1212–1216. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Seeman NC, Lukeman PS. Rep Prog Phys. 2005;68:237–270. doi: 10.1088/0034-4885/68/1/R05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li YG, Tseng YD, Kwon SY, D'Espaux L, Bunch JS, Mceuen PL, Luo D. Nature materials. 2004;3:38–42. doi: 10.1038/nmat1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Teo YN, Kool ET. Chemical reviews. 2012;112:4221–4245. doi: 10.1021/cr100351g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Benvin AL, Creeger Y, Fisher GW, Ballou B, Waggoner AS, Armitage BA. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:2025–2034. doi: 10.1021/ja066354t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Wang F, Lu CH, Willner I. Chemical reviews. 2014;114:2881–2941. doi: 10.1021/cr400354z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kellenberger CA, Wilson SC, Sales-Lee J, Hammond MC. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:4906–4909. doi: 10.1021/ja311960g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Porchetta A, Vallee-Belisle A, Plaxco KW, Ricci F. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:20601–20604. doi: 10.1021/ja310585e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Sharma AK, Heemstra JM. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:12426–12429. doi: 10.1021/ja205518e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Stojanovic MN, de Prada P, Landry DW. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:11547–11548. doi: 10.1021/ja0022223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Kato T, Yano K, Ikebukuro K, Karube I. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:1963–1968. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.9.1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Hannon MJ, Moreno V, Prieto MJ, Moldrheim E, Sletten E, Meistermann I, Isaac CJ, Sanders KJ, Rodger A. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2001;40:880–884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Oleksi A, Blanco AG, Boer R, Uson I, Aymami J, Rodger A, Hannon MJ, Coll M. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2006;45:1227–1231. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Cerasino L, Hannon MJ, Sletten E. Inorganic chemistry. 2007;46:6245–6251. doi: 10.1021/ic062415c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Malina J, Hannon MJ, Brabec V. Chemistry. 2007;13:3871–3877. doi: 10.1002/chem.200700159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Ducani C, Leczkowska A, Hodges NJ, Hannon MJ. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2010;49:8942–8945. doi: 10.1002/anie.201004471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Cardo L, Sadovnikova V, Phongtongpasuk S, Hodges NJ, Hannon MJ. Chem Commun (Camb) 2011;47:6575–6577. doi: 10.1039/c1cc11356a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Phongtongpasuk S, Paulus S, Schnabl J, Sigel RKO, Spingler B, Hannon MJ, Freisinger E. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2013;52:11513–11516. doi: 10.1002/anie.201305079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Dervan PB. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry. 2001;9:2215–2235. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00262-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Chenoweth DM, Meier JL, Dervan PB. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;52:415–418. doi: 10.1002/anie.201205775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Chenoweth DM, Dervan PB. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:14521–14529. doi: 10.1021/ja105068b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Chenoweth DM, Dervan PB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13175–13179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906532106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howell LA, Searcey M. Chembiochem : a European journal of chemical biology. 2009;10:2139–2143. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Lilley DMJ, Clegg RM, Diekmann S, Seeman NC, Vonkitzing E, Hagerman PJ. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3363–3364. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.17.3363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lilley DMJ, Clegg RM, Diekmann S, Seeman NC, Vonkitzing E, Hagerman P. Eur J Biochem. 1995;230:1–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Bartlett PD, Ryan MJ, Cohen SG. J Am Chem Soc. 1942;64:2649–2653. [Google Scholar]; b) Hart H, Shamouilian S, Takehira Y. J Org Chem. 1981;46:4427–4432. [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Swager TM. Accounts of chemical research. 2008;41:1181–1189. doi: 10.1021/ar800107v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Chong JH, MacLachlan MJ. Chemical Society reviews. 2009;38:3301–3315. doi: 10.1039/b900754g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perchellet EM, Wang Y, Lou K, Zhao HP, Battina SK, Hua DH, Perchellet JPH. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:3259–3271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Long TM, Swager TM. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:3826–3827. doi: 10.1021/ja017499x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.a) Chenoweth DM, Harki DA, Dervan PB. Organic letters. 2009;11:3590–3593. doi: 10.1021/ol901311m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Rarig RAF, Tran MN, Chenoweth DM. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:9213–9219. doi: 10.1021/ja404737q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waring MJ, Fox KR, Haylock S. In: Cancer Chemotherapy and Selective Drug Development. Harrap KR, Davis W, Calvert AH, editors. Vol. 23. Springer US: 1984. pp. 377–381. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Makube N, Klump H, Pikkemaat J, Altona C. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;364:53–60. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.a) Pascu GI, Hotze ACG, Sanchez-Cano C, Kariuki BM, Hannon MJ. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2007;46:4374–4378. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hotze ACG, Hodges NJ, Hayden RE, Sanchez-Cano C, Paines C, Male N, Tse MK, Bunce CM, Chipman JK, Hannon MJ. Chemistry & biology. 2008;15:1258–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Richards AD, Rodger A, Hannon MJ, Bolhuis A. Int J Antimicrob Ag. 2009;33:469–472. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Yu HJ, Wang XH, Fu ML, Ren JS, Qu XG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:5695–5703. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Yu HJ, Zhao CQ, Chen Y, Fu ML, Ren JS, Qu XG. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2010;53:492–498. doi: 10.1021/jm9014795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Zhao CQ, Geng J, Feng LY, Ren JS, Qu XG. Chem-Eur J. 2011;17:8209–8215. doi: 10.1002/chem.201100272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Yu HJ, Li M, Liu GP, Geng J, Wang JZ, Ren JS, Zhao CQ, Qu XG. Chem Sci. 2012;3:3145–3153. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hexum JK, Tello-Aburto R, Struntz NB, Harned AM, Harki DA. ACS medicinal chemistry letters. 2012;3:459–464. doi: 10.1021/ml300034a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holliday R. Genet Res. 1964;5:282–304. [Google Scholar]

- 24.a) Kallenbach NR, Ma RI, Seeman NC. Nature. 1983;305:829–831. [Google Scholar]; b) Churchill MEA, Tullius TD, Kallenbach NR, Seeman NC. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:4653–4656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.13.4653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Guo Q, Seeman NC, Kallenbach NR. Biochemistry-Us. 1989;28:2355–2359. doi: 10.1021/bi00432a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Guo Q, Lu M, Seeman NC, Kallenbach NR. Biochemistry-Us. 1990;29:570–578. doi: 10.1021/bi00454a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Lu M, Guo Q, Pasternack RF, Wink DJ, Seeman NC, Kallenbach NR. Biochemistry-Us. 1990;29:1614–1624. doi: 10.1021/bi00458a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Lu M, Guo Q, Seeman NC, Kallenbach NR. Biochemistry-Us. 1990;29:3407–3412. doi: 10.1021/bi00465a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.a) Cassell G, Klemm M, Pinilla C, Segall A. J Mol Biol. 2000;299:1193–1202. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Boldt JL, Pinilla C, Segall AM. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:3472–3483. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309361200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Bolla ML, Azevedo EV, Smith JM, Taylor RE, Ranjit DK, Segall AM, McAlpine SR. Organic letters. 2003;5:109–112. doi: 10.1021/ol020204f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Pan PS, Curtis FA, Carroll CL, Medina I, Liotta LA, Sharples GJ, McAlpine SR. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry. 2006;14:4731–4739. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Brogden AL, Hopcroft NH, Searcey M, Cardin CJ. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2007;46:3850–3854. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.