Abstract

Purpose

There is little evidence comparing complications after intensity-modulated (IMRT) vs. three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy (CRT) for prostate cancer. The study objective was to test the hypothesis that IMRT, compared with CRT, is associated with a reduction in bowel, urinary, and erectile complications in elderly men with nonmetastatic prostate cancer.

Methods and Materials

We undertook an observational cohort study using registry and administrative claims data from the SEER-Medicare database. We identified men aged 65 years or older diagnosed with nonmetastatic prostate cancer in the United States between 2002 and 2004 who received IMRT (n = 5,845) or CRT (n = 6,753). The primary outcome was a composite measure of bowel complications. Secondary outcomes were composite measures of urinary and erectile complications. We also examined specific subsets of bowel (proctitis/hemorrhage) and urinary (cystitis/hematuria) events within the composite complication measures.

Results

IMRT was associated with reductions in composite bowel complications (24-month cumulative incidence 18.8% vs. 22.5%; hazard ratio [HR] 0.86; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.79–0.93) and proctitis/hemorrhage (HR 0.78; 95% CI, 0.64–0.95). IMRT was not associated with rates of composite urinary complications (HR 0.93; 95% CI, 0.83–1.04) or cystitis/hematuria (HR 0.94; 95% CI, 0.83–1.07). The incidence of erectile complications involving invasive procedures was low and did not differ significantly between groups, although IMRT was associated with an increase in new diagnoses of impotence (HR 1.27, 95% CI, 1.14–1.42).

Conclusion

IMRT is associated with a small reduction in composite bowel complications and proctitis/hemorrhage compared with CRT in elderly men with nonmetastatic prostate cancer.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, Comparative effectiveness research, IMRT

INTRODUCTION

Policy makers, clinicians, and the media have highlighted the need for rigorous comparative evaluation of prostate cancer treatments (1, 2). Attention has focused particularly on intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT), given its potential to minimize radiation morbidity and its higher cost in comparison to three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy (CRT).

IMRT is an evolution of CRT. CRT uses customized blocks to shape radiation beams to a tumor volume while minimizing dose to nearby normal organs. IMRT uses beams of nonuniform radiation intensity to deliver radiation dose distributions that better conform to targets with irregular shapes (3). Because the prostate gland is adjacent to both the rectum and the bladder, restricting the volume of surrounding tissue irradiated is particularly important in reducing the morbidity of prostate cancer treatment, including bowel, urinary, and erectile complications (4, 5).

There is little evidence comparing IMRT with CRT for prostate cancer (6). Studies to date have been limited to single institution series (7). Despite calls for a randomized trial comparing IMRT to CRT for prostate cancer, such a trial has not been undertaken. The challenges in conducting a randomized trial likely arise from several factors, including reluctance on the part of clinicians and patients to participate and the rapid adoption of IMRT in the United States (8, 9). Thus, the clinical efficacy of IMRT in terms of limiting bowel, urinary, and erectile morbidity remains unknown.

Under conditions in which randomization is not likely feasible, nonrandomized evidence may provide insights into the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions (10, 11).Therefore, we conducted an observational cohort study to test the hypothesis that IMRT compared to CRT is associated with fewer posttreatment complications in men with nonmetastatic prostate cancer.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Study design

The study was an observational cohort study designed to compare rates of complications after IMRT versus CRT using registry and administrative claims data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER)-Medicare database. The study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Pennsylvania.

Data sources

The SEER-Medicare database links patient demographic and tumor-specific data collected by SEER cancer registries to longitudinal health care claims for Medicare .enrollees in the United States and has been used extensively for observational research (12). Medicare claims result from physician documentation of medical diagnoses and procedures in billing records and can be used to assess the complications of cancer treatments (13). The Medicare program provides healthcare benefits to 97% of the U.S. population aged ≥65 years old. Approximately 94% of patients in SEER aged ≥65 years have been successfully linked with their Medicare claims.

Study population

We identified patients with non-metastatic prostate cancer age 65 years or older diagnosed between January 1, 2002 and December 31, 2004 in SEER with follow-up through December 31, 2006 in Medicare (eAppendix Supplementary Fig. 1). IMRTwas not widely used before 2002, and we allowed for enough follow-up for both IMRT and CRT patients to report 24-month complication outcomes. The primary analytic cohort comprised 5,845 men who received IMRT and 6,753 men who received CRT.

Definition of variables

Treatment

External beam radiotherapy was identified from Medicare inpatient, outpatient, and physician/supplier component files as described previously (14, 15). Delivery of IMRT was identified by the presence of Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes 77418 and G1074 (16). Delivery of CRT was identified by the presence of code 77295 (conformal simulation) or a combination of 77290 (complex simulation) and 76370 (computed tomography guidance for placement of radiotherapy portals).

Outcomes

We identified complications in Medicare claims data by searching for ICD-9 diagnosis codes consistent with possible radiotherapy injury and related ICD-9 or HCPCS/CPT-4 invasive procedure codes according to previously published literature (13, 17–23). We included updated codes through 2006 on the basis of review by clinical experts. Because of concern about the lack of specificity of diagnostic codes alone, we required the presence of both a diagnostic and corresponding procedural code to classify a patient as experiencing the complication in our primary analysis. This approach confined our analyses to what were likely to be the more serious outcomes, comparable to Grade 3 toxicity as measured by the NCI Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events scoring system (i.e., requiring hospital admission or surgical intervention) (24). In sensitivity analyses, we also evaluated diagnoses independent of invasive procedures.

To reduce the possibility that preexisting morbidity would be misclassified as associated with IMRT or CRT, we focused our investigation on new complications from the start of radiotherapy through death or December 31, 2006. Men with codes for complications in the 12 months before the start of radiotherapy were considered to have persistent morbidity and were not included in the analysis of newcomplications. We performed an analysis in which we included patients with prior codes for the complication of interest, and results did not differ substantially from our main findings.

The primary outcome was a composite measure of bowel complications, selected because bowel injury is the limiting toxicity of prostate radiotherapy, and evidence suggests that improvements in radiotherapy technique may lessen bowel morbidity (25, 26). Secondary outcomes were a composite measure of urinary complications and a composite measure of erectile complications. In addition, we examined specific subsets of bowel (proctitis/hemorrhage) and urinary (cystitis/hematuria) events within the composite complication measures because of their clinical relevance.

Composite bowel complications were defined as diagnoses of proctitis or hemorrhage, ulceration, stricture, or fistula of the rectum or anus, intestinal obstruction, pain or incontinence of feces with invasive diagnostic or repair procedures of the anus or rectum. Composite urinary complications were defined as diagnoses of cystitis or hematuria, obstruction, stricture, retention, incontinence or sphincter deficiency, and fistula with invasive urinary diagnostic or repair procedures of the urethra or bladder. Composite erectile complications were defined as diagnoses of impotence and invasive procedures including penile prostheses and intracavernosal injections. Measures of proctitis/hemorrhage and cystitis/hematuria consisted of diagnoses and invasive procedures for these specific conditions. eAppendix Supplementary Table 1 shows Medicare codes used to define complication diagnoses and invasive procedures, and eAppendix Supplementary Table 2 shows the five most common diagnosis and procedure codes for bowel and urinary complications.

Other variables

Patient characteristics were categorized from SEER-Medicare data and analyzed according to the variables shown in Table 1. Patient comorbidities were identified by classifying all available inpatient and outpatient Medicare claims for the 12-month interval preceding prostate cancer diagnosis into 46 categories (27–29). Neither PSA nor radiotherapy dose are reported in SEER-Medicare data.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study cohort

| IMRT |

CRT |

p Value |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | Before adjustment |

After propensity adjustment |

|||

| All patients | 5,845 | (46) | 6,753 | (53.6) | ||

| Patient characteristics | ||||||

| Age at diagnosis | ||||||

| 65–74 years | 3,204 | (55) | 3,684 | (55) | ||

| 75 years or older | 2,641 | (45) | 3,069 | (45) | 0.778 | 0.616 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 4,851 | (83) | 5,707 | (85) | ||

| Black | 521 | (9) | 708 | (10) | ||

| Other | 371 | (6) | 249 | (4) | ||

| Unknown | 102 | (2) | 89 | (1) | <0.0001 | 0.805 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | ||||||

| Not Hispanic | 5,384 | (92) | 6,207 | (92) | ||

| Hispanic | 311 | (5) | 384 | (6) | ||

| Unknown | 150 | (3) | 162 | (2) | 0.569 | 0.903 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 4,153 | (71) | 4,789 | (71) | ||

| Not married | 1,154 | (20) | 1,418 | (21) | ||

| Unknown | 538 | (9) | 546 | (8) | 0.030 | 0.908 |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||

| Tumor stage (AJCC 6th ed.) |

||||||

| T1 | 2,511 | (43) | 2,547 | (38) | ||

| T2 | 3,081 | (51) | 3,908 | (58) | ||

| T3 | 215 | (4) | 230 | (3) | ||

| T4 | 38 | (1) | 68 | (1) | <0.0001 | 0.824 |

| Gleason sum | ||||||

| 8–10 | 1,590 | (27) | 1,937 | (29) | ||

| 5–7 | 4,091 | (70) | 4,603 | (68) | ||

| 2–4 | 61 | (1) | 107 | (2) | ||

| Unknown | 103 | (2) | 106 | (2) | 0.009 | 0.971 |

| History of TURP | ||||||

| No | 5,617 | (96) | 6,432 | (95) | ||

| Yes | 228 | (4) | 321 | (5) | 0.019 | 0.683 |

| Adjuvant androgen suppression |

||||||

| No | 2,225 | (38) | 2,526 | (37) | ||

| Yes | 3,620 | (62) | 4,227 | (63) | 0.445 | 0.909 |

| Comorbidity index* | ||||||

| 0 | 1,470 | (25) | 1,669 | (24) | ||

| 1 | 1,759 | (30) | 2,065 | (31) | ||

| ≥2 | 2,616 | (45) | 3,019 | (45) | 0.786 | 0.921 |

| Demographic characteristics |

||||||

| Year of diagnosis | ||||||

| 2002 | 1,183 | (20) | 3,278 | (49) | ||

| 2003 | 1,911 | (33) | 2,172 | (32) | ||

| 2004 | 2,751 | (47) | 1,303 | (19) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| SEER registry** | ||||||

| San Francisco | 200 | (3) | 239 | (3) | ||

| Connecticut | 474 | (8) | 599 | (9) | ||

| Detroit | 642 | (11) | 890 | (13) | ||

| Hawaii | 156 | (3) | 75 | (1) | ||

| Iowa | 214 | (4) | 589 | (9) | ||

| New Mexico | 203 | (3) | 176 | (3) | ||

| Seattle | 157 | (3) | 387 | (6) | ||

| Utah | 39 | (1) | 109 | (2) | ||

| Atlanta | 97 | (2) | 103 | (1) | ||

| San Jose | 109 | (2) | 153 | (2) | ||

| Los Angeles | 619 | (11) | 250 | (4) | ||

| Greater California | 1,065 | (18) | 1,072 | (16) | ||

| Kentucky | 175 | (3) | 801 | (12) | ||

| Louisiana | 510 | (9) | 376 | (6) | ||

| New Jersey | 1,178 | (20) | 922 | (14) | <0.0001 | 0.418 |

| Population of county of residence | ||||||

| 1,000,000 or more | 3,700 | (63) | 3,326 | (49) | ||

| 250,000 to 999,999 | 1,091 | (19) | 1,317 | (20) | ||

| 0 to 249,999 | 1,054 | (18) | 2,110 | (31) | <0.0001 | 0.025 |

| Median household income in census tract of residence (US$) |

||||||

| 34,000 or less | 1,225 | (21) | 1,828 | (27) | ||

| > 34,000 to 44,000 | 992 | (17) | 1,493 | (22) | ||

| > 44,000 to 60,000 | 1,437 | (25) | 1,741 | (26) | ||

| > 60,000 | 2,191 | (37) | 1,691 | (25) | <0.0001 | 0.123 |

Abbreviations: AJCC = American Joint Committee on Cancer; CRT = three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy; IMRT = intensity-modulated radiotherapy. SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results; TURP = transurethral resection of the prostate.

Comorbidity score of ≥2 represents highest level of comorbidity.

Data not shown for 19 patients in the SEER Rural Georgia registry, according to SEER-Medicare guidelines.

Statistical analysis

We used chi-square tests to compare baseline characteristics between patients receiving IMRT vs. CRT. To balance observed covariates between the IMRT and CRT groups in regression analyses, we used propensity score methods. Propensity scores reflect the probability that a patient will receive therapy on the basis of his observed covariates and can help adjust for selection bias when comparing groups of patients in observational studies (30, 31). For example, patients given CRT may have more severe comorbid disease that may be associated with bowel or urinary complications than those given IMRT. Bowel or urinary complications in these patients may reflect differences in underlying characteristics rather than treatment effects. Propensity score methods try to construct a randomized trial–like comparison between treatment groups that are comparable across observed characteristics. We calculated propensity scores using multivariable logistic regression with receipt of IMRT as the outcome of interest, adjusting for age at diagnosis, race, ethnicity, marital status, T-stage, Gleason sum, history of transurethral resection of the prostate or androgen suppression, comorbidity, diagnosis year, SEER registry, area population, and median income (32). We used chi-square tests to determine whether the covariates were balanced within propensity score quintiles and found that diagnosis year and population size in the county of residence were still not balanced (Table 1).

The Kaplan-Meier method was used to compare estimates of the unadjusted, cumulative incidence of primary and secondary complication outcomes between IMRT and CRT. The observation time for follow-up was calculated as the time from the start date of radiotherapy (determined by the first code for radiotherapy delivery) until either the occurrence of the complication outcome being analyzed or censorship. Patients were censored at death or end of follow-up (December 31, 2006).

To adjust for potential measured confounders, we constructed Cox proportional hazard models to compare complication outcomes between IMRTand CRT, adjusting for propensity score as a continuous variable as well as diagnosis year and area population, which were not balanced after propensity score adjustment. To assess the proportional hazards assumption, we used the Schoenfeld residuals test and complementary log-log plots, and demonstrated that this assumption was not violated in our models (33). In sensitivity analysis, we limited the cohort to men with a minimum follow-up period of 2 years, and results were similar (data not shown).

In observational data sets, it is not always clear why certain patients receive particular treatments. Treatment decisions may be made on the basis of baseline differences between patients that may be prognostically important and that may be measured or unmeasured. When unknown or unmeasured patient characteristics (sometimes called ‘‘hidden bias’’) potentially affect both the decision to treat and the outcome of treatment, bias between patient groups cannot be removed using propensity score methods. To examine the effects of unknown or unmeasured confounders, we performed a sensitivity analysis to assess the potential influence an unmeasured covariate might have on the hazard ratio (HR) estimates of the association between IMRT and complications (29, 34, 35). We varied both the prevalence of the unmeasured covariate in the CRT group and the relative hazard of complications associated with the confounder. Propensity score calculations and survival analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (Cary, NC), and sensitivity analyses were performed using R version 2.7.2 (Vienna, Austria). Statistical significance was set at 0.05, and all tests were two-tailed.

RESULTS

Patient baseline characteristics

The analytic cohort consisted of 12,598 patients diagnosed between 2002 and 2004, of whom 5,845 received IMRT and 6,753 received CRT. Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the two groups. Patients who received IMRT were more likely to reside in areas with larger populations or higher median income and to have earlier stage and lower grade tumors. During the study period, IMRT use increased dramatically.

Unadjusted cumulative incidence of complication outcomes after IMRT vs. CRT

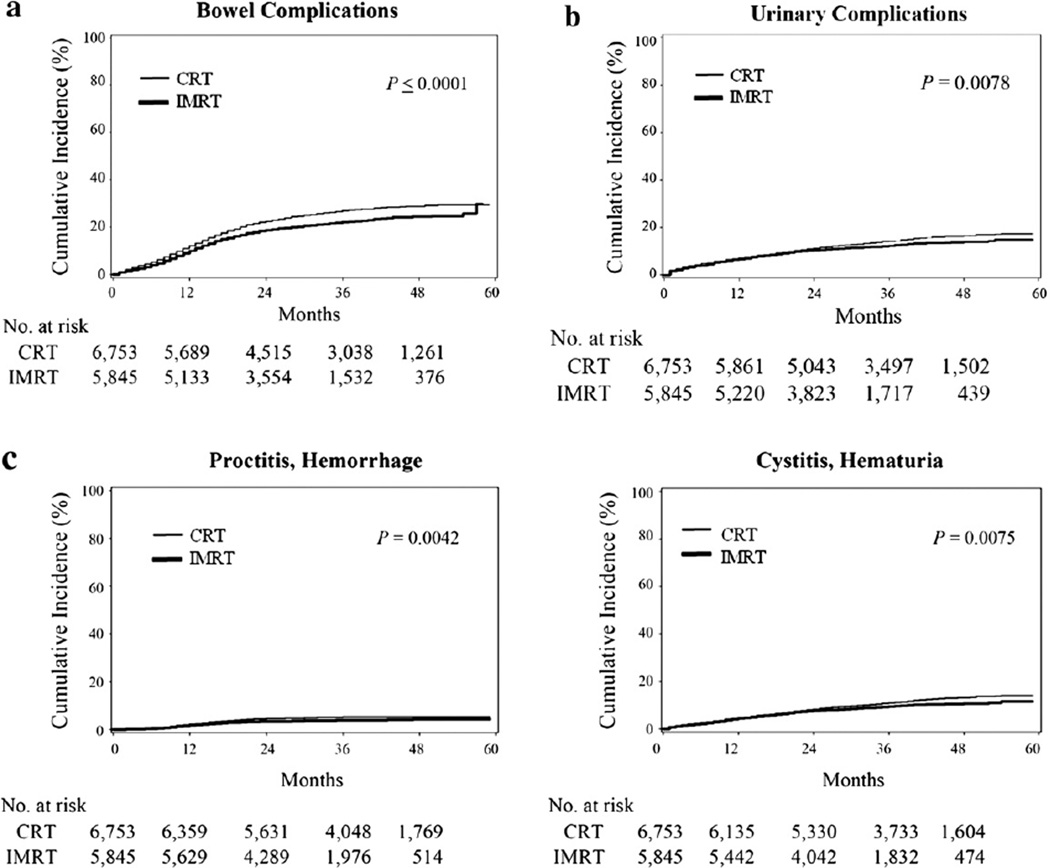

Because of differences in median length of follow-up between men in the IMRT and CRT groups, we evaluated rates of complications over time accounting for censoring. The Kaplan-Meier curve for the estimated cumulative incidence of the primary outcome is shown in Fig. 1a. The incidence of composite bowel complications requiring invasive procedures was less in the IMRT group vs. the CRT group (24-month cumulative incidence of 18.8% vs. 22.5%, Table 2). The incidence of composite urinary complications was lower in the IMRT group (Fig. 1b). The incidence of composite erectile complications involving procedural intervention was low and did not differ significantly between groups. The incidence of proctitis/hemorrhage and cystitis/ hematuria were also lower with IMRT than CRT (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

(a) Cumulative incidence of composite bowel complications requiring an invasive procedure after intensitymodulated (IMRT) and three-dimensional conformal (CRT) radiotherapy. (b) Cumulative incidence of composite urinary complications requiring invasive procedures after IMRT and CRT. (c). Cumulative incidence of subsets of bowel and urinary complications requiring invasive procedures after IMRT and CRT

Table 2.

24-Month cumulative incidence of complications requiring an invasive procedure after intensity-modulated (IMRT) and three-dimensional conformal (CRT) radiotherapy

| IMRT |

CRT |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median follow- up (months)* |

Cohort at risk (24 months) |

24-month estimate, % (95% CI) |

Median follow- up (months)* |

Cohort at risk (24 months) |

24-month estimate, % (95% CI) |

|

| Primary outcome | ||||||

| Bowel complications | 28 | 3,727 | 18.8 (17.8–19.9) | 34 | 4,614 | 22.5 (21.5–23.5) |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||

| Urinary complications | 29 | 3,997 | 10.4 (9.6–11.1) | 37 | 5,145 | 11.2 (10.4–12.0) |

| Erectile complications | 32 | 4,586 | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 41 | 5,946 | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) |

| Subsets of bowel and urinary | ||||||

| complications | ||||||

| Proctitis, hemorrhage | 31 | 4,472 | 3.5 (3.0–4.0) | 40 | 5,723 | 4.5 (4.0–5.0) |

| Cystitis, hematuria | 30 | 4,226 | 7.7 (7.0–8.4) | 39 | 5,433 | 8.3 (7.6–9.0) |

Abbreviation: CI = confidence interval.

Median follow-up for surviving patients.

Adjusted hazard of complication outcomes after IMRT vs. CRT

After adjusting for propensity score, diagnosis year, and area population in Cox models, IMRT was associated with a significant reduction in composite bowel complications (hazard ratio [HR] 0.86; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.79–0.93) and proctitis/hemorrhage (HR 0.78; 95% CI, 0.64–0.95; Table 3). In contrast, the associations between IMRT and reductions in composite urinary complications and cystitis/hematuria were no longer significant.

Table 3.

Association between intensity-modulated radiotherapy and complications requiring an invasive procedure

| Univariate HR for complication |

Multivariable HR for complication* |

|

|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) | (95% CI) | |

| Primary outcomes | ||

| Bowel complications | 0.86 (0.76–0.88) | 0.86 (0.79–0.93) |

| Secondary outcomes | ||

| Urinary complications | 0.87 (0.79–0.97) | 0.93 (0.83–1.04) |

| Erectile complications | 1.30 (0.91–1.88) | 1.50 (1.00–2.24) |

| Subsets of bowel and urinary complications |

||

| Proctitis, Hemorrhage | 0.78 (0.66–0.93) | 0.78 (0.64–0.95) |

| Cystitis, Hematuria | 0.86 (0.77–0.96) | 0.94 (0.83–1.07) |

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio.

Adjusted for propensity score, year of diagnosis, and area population

Cumulative incidence and hazard of complication diagnoses

We performed a sensitivity analysis to evaluate differences in rates of complication diagnoses independent of invasive procedures. Not surprisingly, complication diagnoses were more frequent than complications with invasive procedures (eAppendix Supplementary Fig. 2). The incidence of bowel diagnoses was less in the IMRT group than the CRT group, whereas the incidence of urinary diagnoses did not differ significantly between the groups. The incidence of new impotence diagnoses was higher in the IMRT group vs. the CRT group (24-month cumulative incidence of 15.6% vs. 12.6%). In Cox models adjusted for propensity score, diagnosis year, and area population, hazards of complication diagnoses associated with IMRT vs. CRT were very similar to the main analysis of complications with invasive procedures (eAppendix Supplementary Table 2). IMRTwas associated with a significant increase in impotence diagnoses in unadjusted (HR 1.28, 95% CI, 1.16–1.41) and adjusted (HR 1.27, 95% CI, 1.14–1.42) proportional hazards models.

Effect of an unmeasured confounder

In nonrandomized studies, an observed association between treatment and outcome may reflect the effects of unmeasured confounders. Poor functional status is an example of an unmeasured confounder that may be relevant to the cohort and outcomes under study that is not recorded in SEER-Medicare data. The strength of the association between IMRTand complications is affected by (1) the prevalence of the unmeasured confounder in the IMRT group, (2) the prevalence of the unmeasured confounder in the CRT group, and (3) the hazard associated with the unmeasured confounder (which is assumed to be the same in the IMRT and CRT groups).

The sensitivity analysis for the primary outcome is shown in Table 4 and is based on the estimated adjusted hazard ratio for composite bowel complications for IMRT vs. CRT (0.86, 95% CI, 0.79–0.93). We set the prevalence of the unmeasured confounder in the IMRT group at 10%, which is in the range, for example, of prevalence estimates of poor functional status or disability among the elderly (36). We then varied the prevalence of the unmeasured confounder in the CRT group to determine the extent to which its distribution would need to be imbalanced between the groups to influence the statistical significance of the results (i.e., the upper bound of the 95% CI crosses 1.0). For example, if the unmeasured confounder were a moderate confounder, increasing the risk of complications by 50% (HR 1.50), the estimated hazard ratio would be significantly affected if the prevalence of the unmeasured confounder in the IMRT and CRT groups were threefold different (i.e., 30% prevalence in the CRT group but only 10% prevalence in the IMRT group). Under these conditions, our results would no longer be significant.

Table 4.

Sensitivity analysis estimating the effect of an unmeasured confounder on the hazard ratio of bowel complications after intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT)

| Prevalence of UC in IMRT group | Prevalence of UC in CRT group | UC HR | Treatment HR adjusted for UC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.10 | 0.3 | 1.25 | 0.90 (0.83, 0.98) |

| 0.10 | 0.4 | 1.25 | 0.92 (0.85, 0.99) |

| 0.10 | 0.5 | 1.25 | 0.94 (0.87, 1.02) |

| 0.10 | 0.2 | 1.50 | 0.90 (0.83, 0.97) |

| 0.10 | 0.3 | 1.50 | 0.94 (0.86, 1.02) |

| 0.10 | 0.2 | 1.75 | 0.92 (0.85, 0.99) |

| 0.10 | 0.3 | 1.75 | 0.98 (0.90, 1.06) |

| 0.10 | 0.2 | 2.0 | 0.94 (0.86, 1.01) |

Abbreviations: CRT = three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy; HR = hazard ratio; UC = unmeasured confounder.

The rows in bold highlight situations in which the unmeasured confounder is strong enough to influence the significance of the results (e.g., the upper bound of the 95% CI crosses 1).

DISCUSSION

We conducted this study to compare complications after IMRT vs. CRT in a population-based cohort of men with nonmetastatic prostate cancer. Analyzing administrative claims data from patients diagnosed between 2002 and 2004 in the United States, we found that IMRT was associated with a small reduction in a composite measure of bowel complications as well as the specific complications of proctitis/hemorrhage. Measures of urinary complications did not differ significantly between patients treated with IMRT vs. CRT. Although erectile complications involving invasive procedures were rare in both treatment groups, IMRT was associated with a moderate increase in new diagnoses of impotence compared with CRT.

The lower rate of bowel complications we observed is consistent with the reduced proportion of rectum exposed to higher doses of radiation with IMRT (25). Minimal differences in urinary side effects between IMRTand CRT may be explained because a portion of bladder neck and prostatic urethra are included in the irradiated target volume regardless of radiotherapy technique (37).

Our findings are consistent with and extend those of previous studies examining technological improvements in radiotherapy delivery. The only randomized comparison between different radiotherapy techniques for patients with prostate cancer compared CRT to conventional radiation therapy, a two-dimensional technique employed before the introduction of CRT that used rectangular irradiation fields rather than three-dimensional imaging to shape the radiation beam to the prostate (26). Fewer patients developed radiation-induced proctitis in the CRT group vs. the conventional group, whereas there were no significant differences in rates of cystitis. The proportion of patients experiencing Grade ≥3 proctitis (i.e., requiring hospital admission or procedural intervention) in this study and other controlled trials of CRT, using radiation doses ranging from 64 to 78 Gy, has ranged from 0% to 7% (26, 38–40).

A recent systematic review of IMRT identified five published studies in which late toxicity data was compared between IMRT and CRT, and we identified one additional study based on a comprehensive search (7, 41–46). Table 5 summarizes these studies and compares results to our findings. Although differences exist between patient characteristics in the IMRT and CRT groups and several studies used historical controls from the previous decade (42, 44, 47), the limited evidence available shows that IMRT is generally associated with lower rates of Grade ≥3 proctitis (range, 1%–6%), compared with CRT (range, 2%–21%). Taken together, the magnitude and direction of the IMRT treatment effect from these studies is very similar to the rates of proctitis/hemorrhage (the most comparable endpoint) in our population-based cohort. This evidence provides some external validity of our outcome measures but also highlights the fact that any improvement with IMRT, although perhaps measurable and important, will be modest in absolute terms. Our study augments the existing literature by examining a large and broad population of patients and adjusting for known confounders, including an extensive set of comorbidities ascertained from Medicare data.

Table 5.

Summary of studies comparing late rectal and urinary toxicity after intensity-modulated (IMRT) and three-dimensional conformal (CRT) radiotherapy

| Study | Follow-up median/ reported (months) |

Definition | IMRT |

CRT |

Late rectal toxicity |

Late urinary toxicity |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Dose | n | Dose | IMRT | CRT | pvalue | IMRT | CRT |

P value |

|||

| Shu 200143 | 23/10 | RTOG Gr. ≥2 | 18 | 85 Gy | 26 | 84 Gy | NR | NR | 0.163 | NR | NR | 0.025 |

| Kupelian 200241 | 25/30 | RTOG Gr. 3 | 166 | 70 Gy/2.5 Gy | 116 | 78 Gy | 2% | 8% | 0.059 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Sanguineti 200642 | 26/24 | RTOG Gr. ≥2 | 45 | 76 Gy | 68 | 76 Gy | 6% | 21% | 0.06 | NR | NR | NR |

| Vora 200744 | 60/60 | RTOG Gr. 3 | 145 | 75.6 Gy | 271 | 68.4 Gy | 1% | 2% | 0.24 | 6% | 5% | 0.33 |

| Zelefsky 200845 | 96/120 | CTC ≥Gr. 2 | 472 | 81 Gy | 358 | ≤75.6 Gy | 5% | 13% | <0.001 | 20% | 12% | 0.01 |

| Odrazka 201046 | 53/36 | RTOG Gr. 3 | 112 | 78 Gy | 228 | 70 Gy | 2% | 5% | 0.20 | 5% | 16% | 0.01 |

| Bekelman 2011 | 36/24 | Medicare claims* | 5,845 | NA | 6,753 | NA | 3.5% | 4.5% | 0.01** | 7.7% | 8.3% | 0.19** |

Abbreviations: CTC = Common Toxicity Criteria; Gr = Grade; NA = not applicable; NR = not reported; RTOG = Radiation Therapy Oncology Group.

Based on Medicare claims for diagnoses and procedures consistent with proctitis/hemorrhage or cystitis/hematuria

Adjusted p.

The finding that IMRT is associated with increased new diagnoses of impotence raises several important questions. Although a growing literature describes the use of IMRT to limit the dose of radiation to presumed erectile structures, the etiology of erectile dysfunction after radiotherapy remains poorly established (48, 49). Because IMRT increases radiation dose heterogeneity (e.g., ‘‘hot spots’’) compared with CRT (50), IMRT may result in higher doses of radiation to erectile structures and higher rates of subsequent impotence. In addition, radiotherapy dose escalation has been facilitated by IMRT, and it is possible that men in the IMRT group were treated with higher overall doses of radiation than men in the CRT group. Systematic differences in radiotherapy dose, which are not recorded in SEERMedicare data, may contribute to the observed differences in erectile dysfunction. However, the measurement of impotence from Medicare claims data is well known to be challenging and to underestimate actual rates of erectile dysfunction (13). Moreover, men who were early adopters of IMRT may be intrinsically more likely to pursue medical care than those who received CRT. This bias may result in a higher rate of claims-based detection of impotence among men undergoing IMRT, thereby inflating the association between IMRT and impotence.

Because our study design was observational rather than randomized, our results must be interpreted within the context of the limitations of observational research (51). The propensity score approach reasonably adjusts for potential bias due to measured confounders and revealed little material change in the IMRT treatment effect across study endpoints. However, residual bias due to unmeasured confounders remains a challenge for observational research (52). In addition, the statistically significant treatment effect we report for the primary outcome is of moderate strength and thus possibly sensitive to systematic bias (53, 54). In the sensitivity analysis, we found that the statistical significance of the observed association between IMRT and reduced bowel complications could be eliminated under what would be considered extreme scenarios (i.e., an unmeasured confounder, such as poor functional status, would need to have an increased risk of bowel complications of 1.5- and a 3-fold difference in prevalence between the CRT and IMRT groups); however, such situations are plausible in a broadly representative population-based cohort.

Given the challenges in conducting randomized trials in this area, complementary observational studies with more extensive clinical data, including clinician- or patient-reported toxicity measures, would be helpful, particularly for disentangling the possible relationship between IMRT and erectile dysfunction. For example, cancer cooperative groups could retrospectively analyze prospective clinical trials in which both IMRT and CRT where used. The creation of registries with patientreported outcomes would also be an important contribution. Moreover, the gap in randomized evidence for new medical technology that is highlighted by the case of IMRTunderscores the need and opportunity to design efficient, pragmatic clinical trials as new therapies are developed (55).

Using Medicare claims data to study the complications of cancer treatment has limitations. Medicare billing codes are an imperfect measure of complications, particularly when the complication does not involve further procedures. Although we assume that new, posttreatment Medicare claims related to bowel, urinary, or erectile morbidity reflect complications from radiotherapy, there may be several reasons for these claims, possibly leading to higher complication estimates (18). For example, physicians may be particularly diligent about documenting diagnoses of morbidity for billing purposes, even though the incidence of serious complications requiring procedural intervention is lower. In the primary analysis, our outcome measures required the presence of both a procedure and diagnosis billing code, thereby maximizing the specificity of the measure for serious complications. Although this approach underestimates the rates of less severe complications that do not involve a procedure, the results of sensitivity analyses using diagnoses alone were very similar to the primary analyses for both bowel and urinary complications. Furthermore, any misclassification of Medicare claims is likely to be nondifferential (e.g., equal among men in the IMRT and CRT groups) or potentially biased in favor of the CRT group (men who are early adopters of IMRT are also more likely to seek medical attention for their complications) (13). It is important to note as well that we are unable to ascertain more minor complications consistent with clinicianreported Grade 1 or 2 toxicity.

Although IMRT was associated with a small reduction in composite bowel complications (our primary endpoint), our results show that approximately one in five patients experienced such complications requiring an invasive procedure at 24 months. When used to assess complications of cancer treatment, Medicare claims measure the incidence of interventions rather than the prevalence of adverse function (12). The incidence of interventions after radiotherapy among this U.S. population–based cohort may reflect, in part, U.S.-specific practice patterns consistent with health services overutilization (2). In addition, although we adjusted for known covariates that may increase the likelihood of complications after treatment, we could not characterize baseline bowel, urinary, or erectile function on the basis of Medicare billing codes. Also, early vs. late or transient vs. chronic radiotherapy complications cannot be reliably ascertained from SEERMedicare data.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that IMRT is associated with a small reduction in composite bowel complications and proctitis/hemorrhage compared to CRT in elderly men with nonmetastatic prostate cancer. Our results have both internal and external validity. They are biologically plausible based on established dose–volume–outcome principles of radiotherapy. The selected outcomes are confined to diagnoses consistent with radiotherapy injury and associated with invasive procedures likely to be well documented in claims data (13). Although restricted to men aged 65 years and older, findings from this population-based cohort are generalizable to the great majority of men who receive radiotherapy for prostate cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This study used the linked Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare database. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Program, National Cancer Institute (NCI), the Office of Research, Development and Information, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), Information Management Services (IMS), Inc., and the SEER Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database.

This paper was supported in part by funds from Grant No. IRG-78–002–29 from the American Cancer Society.

Footnotes

The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Dr. Bekelman had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Conflicts of interest: Dr. Bekelman reports serving as a consultant for the Riverside Company and receiving grants to his institution from the American Cancer Society and philanthropic sources. Dr. Armstrong reports receiving grants to her institution from the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Defense, the American Cancer Society, and the RobertWood Johnson Foundation. All other authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material cited in this article is available online.

REFERENCES

- 1.Leonhardt D. New York Times. 2009. Jul 7, In health reform, a cancer offers an acid test. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emanuel EJ, Fuchs VR. The perfect storm of overutilization. JAMA. 2008;299:2789–2791. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.23.2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ling CC, Burman C, Chui CS, et al. Conformal radiation treatment of prostate cancer using inversely-planned intensity-modulated photon beams produced with dynamic multileaf collimation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;35:721–730. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(96)00174-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bentzen SM, Constine LS, Deasy JO, et al. Quantitative Analyses of Normal Tissue Effects in the Clinic (QUANTEC): An introduction to the scientific issues. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76(3 Suppl.):S3–S9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emami B, Lyman J, Brown A, et al. Tolerance of normal tissue to therapeutic irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;21:109–122. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90171-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilt T, Shamliyan T, Taylor B, et al. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 13. Prepared by Minnesota Evidence-based Practice Center under contract no. 290-02-0009. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. Comparative effectiveness of therapies for clinically localized prostate cancer. Available at, http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/reports/final.cfm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hummel S, Simpson E, Hemingway P, et al. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy for the treatment of prostate cancer: A systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technology Assessment. 2010;14 doi: 10.3310/hta14470. Available at, http://www.hta.ac.uk/fullmono/mon1447.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bentzen SM. Randomized controlled trials in health technology assessment: Overkill or overdue? Radiother Oncol. 2008;86:142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mell LK, Mehrotra AK, Mundt AJ. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy use in the U.S., 2004. Cancer. 2005;104:1296–1303. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Black N. Why we need observational studies to evaluate the effectiveness of health care. BMJ. 1996;312:1215–1218. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7040.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rawlins M. De testimonio: On the evidence for decisions about the use of therapeutic interventions. Lancet. 2008;372:2152–2161. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61930-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Potosky AL, Riley GF, Lubitz JD, et al. Potential for cancer related health services research using a linked Medicaretumor registry database. Medical Care Aug. 1993;31:732–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Potosky AL, Warren JL, Reidel ER, et al. Measuring complications of cancer treatment using the SEER-medicare data. Med Care. 2002;40(Suppl. 8):IV62–IV68. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bekelman JE, Zelefsky MJ, Jang TL, et al. Variation in adherence to external beam radiotherapy quality measures among elderly men with localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:1456–1466. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jang TL, Bekelman JE, Liu Y, et al. Physician visits prior to treatment for clinically localized prostate cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:440–450. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.CMSManual System. Centers for Medicare& Medicaid Services (CMS). Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS). Pub. No. 100–04 Medicare Claims Processing Transmittal 1139. Change Request 5438. 2006 Dec 22; Available at http://www.cms.hhs.gov/transmittals/downloads/R1139CP.pdf.

- 17.Chen A, DAmico A, Neville B, Earle C. Provider case volume and outcomes following prostate brachytherapy. J Urol. 2009;181:113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen A, DAmico A, Neville B, Earle C. Patient and treatment factors associated with complications after prostate brachytherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5298–5304. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alibhai S, Leach M, Warde P. Major 30-day complications after radical radiotherapy: A population-based analysis and comparison with surgery. Cancer. 2009;15:293–302. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Begg CB, Riedel ER, Bach PB, et al. Variations in morbidity after radical prostatectomy [see comment] New Engl J Med. 2002;346:1138–1144. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa011788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu-Yao G, Albertsen P, Warren J, Yao S. Effect of age and surgical approach on complications and short-term mortality after radical prostatectomy—a population-based study. Urology. 1999;54:301–307. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)00100-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu JC, Xiangmei G, Lipsitz S, et al. Comparative effectiveness of minimally invasive vs open radical prostatectomy. JAMA. 2009;302:1557–1564. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anger J, Litwin M, Wang Q, et al. The effect of age on outcomes of sling surgery for urinary incontinence. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:1927–1931. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) National Institutes of Health. National Cancer Institute. Available at http://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.02_2009-09-15_QuickReference_5×7.pdf.

- 25.Michalski JM, Gay H, Jackson A, et al. Radiation dose–volume effects in radiation-induced rectal injury. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76(Suppl. 1):S123–S129. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.03.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dearnaley DP, Khoo VS, Norman AR, et al. Comparison of radiation side-effects of conformal and conventional radiotherapy in prostate cancer: A randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;353:267–272. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)05180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silber J, Rosenbaum P, Trudeau M, et al. Multivariate matching and bias reduction in the surgical outcomes study. Med Care. 2001;39:1048–1064. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200110000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong YN, Mitra N, Hudes G, et al. Survival associated with treatment vs observation of localized prostate cancer in elderly men. JAMA. 2006;296:2683–2693. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.22.2683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rubin D. Estimating causal effects from large data sets using propensity scores. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:757–763. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-8_part_2-199710151-00064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenbaum P, Rubin D. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brookhart MA, Schneeweiss S, Rothman KJ, et al. Variable selection for propensity score models. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:1149–1156. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Collett D. Modelling survival data in medical research. 2nd ed. New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mitra N, Heitjan DF. Sensitivity of the hazard ratio to nonignorable treatment assignment in an observational study. Stat Med. 2007;26:1398–1414. doi: 10.1002/sim.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin D, Psaty B, Kronmal R. Assessing the sensitivity of regression results to unmeasured confounders in observational studies. Biometrics. 1998;54:948–963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spillman B. Changes in elderly disability rates and the implications for health care utilization and cost. Milbank Q. 2004;82:157–194. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00305.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Viswanathan AN, Yorke ED, Marks LB, et al. Radiation dose/ volume effects of the urinary bladder. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:S116–S122. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.02.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dearnaley DP, Sydes MR, Graham JD, et al. Escalated-dose versus standard-dose conformal radiotherapy in prostate cancer: first results from the MRC RT01 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:475–487. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuban DA, Tucker SL, Dong L, et al. Long-term results of the M. D. Anderson randomized dose-escalation trial for prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peeters ST, Heemsbergen WD, Koper PC, et al. Dose-response in radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer: results of the Dutch multicenter randomized phase III trial comparing 68Gy of radiotherapy with 78 Gy. J ClinOncol. 2006;24:1990–1996. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kupelian PA, Reddy CA, Carlson TP, et al. Preliminary observations on biochemical relapse-free survival rates after shortcourse intensity-modulated radiotherapy (70 Gy at 2.5 Gy/ fraction) for localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53:904–912. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02836-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanguineti G, Cavey ML, Endres EJ, et al. Does treatment of the pelvic nodes with IMRT increase late rectal toxicity over conformal prostate-only radiotherapy to 76 Gy? Strahlenther Onkol. 2006;182:543–549. doi: 10.1007/s00066-006-1586-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shu HK, Lee TT, Vigneauly E, et al. Toxicity following highdose three-dimensional conformal and intensity-modulated radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. Urology. 2001;57:102–107. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00890-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vora SA, Wong WW, Schild SE, et al. Analysis of biochemical control and prognostic factors in patients treated with either low-dose three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy or high-dose intensity-modulated radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68:1053–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zelefsky MJ, Levin EJ, Hunt M, et al. Incidence of late rectal and urinary toxicities after three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy and intensity-modulated radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:1124–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Odrazka K, Dolezel M, Vanasek J, et al. Late toxicity after conformal and intensity-modulated radiation therapy for prostate cancer: Impact of previous surgery for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Int J Urol. 2010;17:784–790. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2010.02592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chu KC, Tarone RE, Freeman HP. Trends in prostate cancer mortality among black men and white men in the United States. Cancer. 2003;97:1507–1516. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roach M, Nam J, Gagliardi G, et al. Radiation dose–volume effects and the penile bulb. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76(Suppl. 1):S130–S134. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.04.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buyyounouski MK, Horwitz EM, Price RA, et al. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy with MRI simulation to reduce doses received by erectile tissue during prostate cancer treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58:743–749. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(03)01617-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luxton G, Hancock SL, Boyer AL. Dosimetry and radiobiologic model comparison of IMRT and 3D conformal radiotherapy in treatment of carcinoma of the prostate. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59:267–284. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lawlor DA, Smith GD, Bruckdorfer KR, et al. Those confounded vitamins: What can we learn from the differences between observational versus randomised trial evidence? Lancet. 2004;363:1724–1727. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bosco JLF, Silliman RA, Thwin SS, et al. A most stubborn bias: No adjustment method fully resolves confounding by indication in observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;63:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Glasziou P, Chalmers I, Rawlins M, McCulloch P. When are randomised trials unnecessary? Picking signal from noise. BMJ. 2007;334:349–351. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39070.527986.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Doll R, Peto R. Randomised controlled trials and retrospective controls. Br Med J. 1980;280:44. doi: 10.1136/bmj.280.6206.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luce BR, Kramer JM, Goodman SN, et al. Rethinking randomized clinical trials for comparative effectiveness research: The need for transformational change. Ann Int Med. 2009;151:206–209. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-3-200908040-00126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.