Abstract

Objective

We sought to evaluate the extent to which major depressive disorder (MDD) is associated with cardiometabolic diseases and risk factors.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional epidemiologic study of 1,924 employed adults in Ethiopia. Structured interview was used to collect sociodemographic data, behavioral characteristics and MDD symptoms using a validated Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) depression scale. Fasting blood glucose, insulin, C-reactive protein, and lipid concentrations were measured using standard approaches. Multivariate logistic regression models were fitted to estimate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

Results

A total of 154 participants screened positive for MDD on PHQ-9 (8.0%; 95% CI 6.7-9.2%). Among women, MDD was associated with more than 4-fold increased odds of diabetes (OR=4.14; 95% CI:1.03-16.62). Among men the association was not significant (OR=1.04; 95% CI: 0.35-3.05). Similarly, MDD was not associated with metabolic syndrome among women (OR=1.51; 95% CI: 0.68-3.29) and men (OR=0.61; 95% CI: 0.28-1.34). Lastly, MDD was not associated with increased odds of systemic inflammation.

Conclusion

The results of our study do not provide convincing evidence that MDD is associated with cardiometabolic diseases among Ethiopian adults. Future studies need to evaluate the effect of other psychiatric disorders on cardiometabolic disease risk.

Keywords: Cardiovascular Diseases, Africa, Ethiopia, Depression

Introduction

The global prevalence of cardiometabolic risk such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes and obesity is increasing at an alarming rate, with the majority of cases occurring in low and middle income countries [1]. A growing body of epidemiologic evidence shows that incidence of cardiometabolic diseases are increasing in sub-Saharan Africa [2-6]. Kearney at al. reported that in the year 2000 an estimated 639 million individuals had hypertension in low and middle income countries and this number is expected to rise to 1.15 billion by 2025 [7]. In 2006, 10.8 million sub-Saharan Africans were estimated to have diabetes. This number is expected to rise to 18.7 million by 2025 [8]. The rise in cardiometabolic disease prevalence is driven, in part, by significant changes in dietary habits, physical activity levels, and increased stress as a result of increased urbanization and economic development [1]. An expanding body of evidence now implicates unipolar major depressive disorder (MDD) as one of the major risk factors for and conditions co-occurring with cardiometabolic disease [9-11]. Several studies, primarily conducted in developed countries, have documented associations of MDD with cardiometabolic disease including hypertension, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, myocardial infarction, sudden death, and other cardiac events [12-15]. Some investigators, however, have found no significant associations between cardiometabolic disease risk and MDD [16-18]. Reasons for these inconsistent findings are unclear.

Although causal relationships, and biological mechanisms underlying associations of MDD with cardiometabolic diseases have yet to be clearly established, understanding the epidemiological characteristic of these disorders (e.g., assessment of comorbidity) may help inform health promotion and disease control efforts[11]. For example, investigators have reported that individuals with comorbid diabetes and MDD are more likely than individuals with diabetes alone to have poor glycemic control and consequently to have more severe complications and lower quality of life [11, 19]. Given the increased burden of cardiometabolic disease risk and the available body of evidence documenting the association between MDD and cardiometabolic disease risk, we sought to evaluate the extent to which MDD is associated with cardiometabolic disease risk factors among an epidemiologically well characterized occupational cohort of bankers and teachers residing in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Materials & Methods

Design and Participants

This study was conducted in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, during the months of December 2009 and January 2010. Study participants were permanent employees of the Commercial Bank of Ethiopia and teachers in government and public schools of Addis Ababa. These workplaces were selected based on their high stability of workforce and willingness to participate in the study. Multistage sampling was done by means of probability proportional to size (PPS) sampling [20]. This was performed for both institutions, and all individuals at selected locations were invited to participate. The original study population was comprised of 2,207 individuals. Subjects were excluded due to missing anthropometric information (n=35), pregnancy (n=21), and incomplete laboratory measures (n=227), the final analytical sample included 1,924 (1,165 men and 759 women) participants. Participants who were excluded were similar in sociodemographic and lifestyle characteristics to those who were included in the analysis.

Data Collection and Variable Specification

Each participant was interviewed by a trained interviewer in accordance with the WHO STEPwise approach for non-communicable diseases surveillance in developing countries [21]. The approach had three levels: (1) questionnaire to ascertain demographic and behavioral characteristics, (2) simple physical measurements, and (3) biochemical tests. Some questions were added to supplement the WHO questionnaire reflect on the local context. Questions were also included regarding behavioral risk factors such as tobacco, alcohol, and khat consumption. Khat is an evergreen plant with amphetamine-like effects commonly used as a mild stimulant for social recreation and to improve work performance in Ethiopia [22, 23]. The modified questionnaire was first written in English and then translated into Amharic by experts and was translated back in to English. The questionnaire was pre-tested before the initiation of the study and contained information regarding socio-demographic characteristics, tobacco and alcohol use, nutritional status, and physical activity. A five-day training of the contents of the STEPs questionnaire, data collection techniques, and ethical conduct of human research was provided to research interviewers prior to the commencement of the study. . Details regarding data collection methods and study procedures have been previously described in detail [5, 24]

Cardiometabolic Disease Risk Factors

Blood pressure was digitally measured (Microlife BP A50, Microlife AG, Switzerland) after individuals had been resting for five minutes. Two additional blood pressure measurements were taken with three minutes elapsing between successive measurements. In accordance with the WHO recommendation the mean systolic and diastolic BP from the second and third measurements were considered for analyses. For the collection of blood samples, individuals were advised to skip meals for 12 hours. Blood samples of 12 mL were obtained, using proper sanitation and infection prevention techniques. The collected aliquots of blood were used to determine participants' fasting blood glucose (FBG) concentrations and lipid profiles. Serum was used for the measurement of triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), glucose concentrations, insulin and C-reactive protein (CRP). These were measured at the International Clinical Laboratory (ICL) in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. ICL is the only clinical laboratory in East Africa accredited by the Joint Commission International (JCI) of USA. TG concentrations were determined by standardized enzymatic procedures using glycerol phosphate oxidase assay. HDL-C was measured using the Ultra HDL assay which is a homogeneous method for directly measuring HDL-C concentrations in serum or plasma without the need for off-line pretreatment or centrifugation steps. Participants' FBG was determined using the standardized glucose oxidase method. Serum CRP concentrations were measured by an ultrasensitive competitive immunoassays. All laboratory assays were completed without knowledge of participants' medical history. Lipid, lipoprotein and FBG concentrations were reported as mg/dL and CRP as mg/L.

Height and weight were measured with participants wearing light clothing and no shoes[21]. Waist circumference measurements were performed with a fixed tension tape, at the midpoint between the lower margin of the last palpable rib and the top of the iliac crest. This was done in a private place over light clothing. Hip circumference measurements were conducted in a similar manner, at the point of the maximum circumference of the buttocks.

Analytical Variable Specification

Metabolic Syndrome

We defined abdominal obesity using the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) criteria [25] where those having a waist circumference of ≥94 cm for men and ≥80 cm for women. Low HDL-C was defined to be <40 mg/dL in men and <50 mg/dL in women. We defined elevated blood pressure as having systolic blood pressure (SBP) of ≥135 mmHg or a diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥85 mmHg. Impaired fasting glucose was defined to be ≥100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) or with a previous history of diabetes. Elevated TG was defined as ≥150 mg/dL. Metabolic syndrome was defined in accordance with the IDF as presence of abdominal obesity and presence of two or more metabolic syndrome components described above [25].

According to the definitions of the American Heart Association and the National Cholesterol Education Program [26] we grouped fasting blood glucose in to normal (<100 mg/dL), impaired fasting glucose (100-125 mg/dL), and diabetes (≥126 mg/dL or a previous history of diabetes or currently on medication). LDL concentrations were classified as: optimal (<100 mg/dL); near or above optimal (100-129 mg/dL); and high (≥130 mg/dL). Total cholesterol concentrations were classified as: desirable (<200 mg/dL), borderline high (200-239 mg/dL), and high (≥ 240 mg/dL). HDL concentrations levels were grouped as: low (<40 mg/dL), normal, (40-59 mg/dL), and high (≥60 mg/dL). We grouped triglyceride concentrations as: desirable (<200 mg/dL), borderline high (200-239 mg/dL), and high (≥ 240 mg/dL).

Insulin Resistance Syndrome and C-reactive Protein

Furthermore, we implemented a nested, case–control design based on metabolic syndrome status within the entire cohort to assess the extent to which insulin resistance syndrome (a condition in which peripheral tissues become nonresponsive to the effects of insulin) and C-reactive protein (marker of systemic inflammation) are associated with MDD. This was done first by stratifying the study cohort according to the presence or absence of metabolic syndrome. Next, we selected all participants with metabolic syndrome (case group). Then, we randomly selected those without metabolic syndrome (control group). A total of 516 participants (156 metabolic syndrome cases and 360 controls) were selected for this nested case-control analysis. The age and sex distribution of those included in the nested analyses were similar to those not included. As an index of insulin resistance, we determined the Homeostatis Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) index by dividing the product of fasting glucose (mg/dl) and fasting insulin (μIU/ml) by 405 [27]. The HOMA IR is widely used in clinical trials and has been shown to be correlated with the results obtained from the &ldquogold standard&rdquo euglycemic glucose clamp method [28]. We evaluated the presence of insulin resistance syndrome based on the upper 10th percentile of HOMA-IR values for normal-weight male and female subjects with normal fasting blood glucose in this study. This is an approach that has been used by other investigators [29]. Categories of CRP were defined using tertiles (based on the distribution among controls). The groups with the lowest two tertiles were defined as low CRP (reference group) and the group with the highest tertile as high CRP.

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD)

We used the PHQ-9 to classify participants with regard to MDD. Because of its brevity, the PHQ-9 has gained increased recognition as a preferred instrument for depression screenings and diagnosis in research and primary care settings among racially and ethnically diverse populations [30, 31]. The PHQ-9 items queries participants about the frequency of nine depressive symptoms experienced. Scores for each question range from 0 (“not at all”) to 3 (“nearly every day”). The PHQ-9 total score is the sum of scores for the nine items for each participant, and ranged from 0-27. A score of ≥ 9 on the Amharic version of PHQ-9 is associated with 90% sensitivity and 62% specificity in diagnosing “major depressive disorder” using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) criteria[32]. Therefore, we defined presence of MDD using a score ≥9 on PHQ-9.

Covariates

Participants were classified according to their alcohol consumption habits: nondrinker (< 1 alcoholic beverage a week), moderate (1–21 alcoholic beverages a week), and high to excessive consumption (> 21 alcoholic beverages a week) according to the WHO classification [33]. Other variables were categorized as follows: age (years), sex (male, female), education (≤ high school, technical school, ≥ college education), smoking history (never, former, current), and current Khat consumption (yes, no). Participants were also asked the following question about their self-reported health status: “Would you say your health in general is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” We classified those who reported fair or poor health and those who reported excellent, very good, or good health. All participants provided informed consent, and the research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Addis Continental Institute of Public Health, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and the Human Subjects Division at the University of Washington, USA.

Statistical Analysis

Subjects' characteristics were summarized using means (± standard deviation) for continuous variables and counts and percentages for categorical variables. For skewed variables median [interquartile range] were provided. Differences in categorical variables were evaluated using Chi-square test. For continuous variables with normal distributions, Student's t tests were used to evaluate differences in mean values by depression status. We used unadjusted and multivariable-adjusted logistic regression models to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the association between cardiometabolic risk and presence of MDD. Conditional logistic regression procedures were used for the nested case control samples. Confounding was assessed by entering potential confounders into a logistic model one at a time, and then comparing the unadjusted and adjusted ORs. Final logistic regression models included covariates that altered unadjusted ORs by at least 10% [34]. Finally, we assessed for any evidence of modification in the magnitude of effect in participants with and without cardiometabolic risk by including an interaction term between MDD and potential effect modifiers. Evidence for effect modification was assessed in Likelihood Ratio Tests comparing the goodness of fit of models with and without the interaction term. We considered the following variables, a priori, as potential confounders and/or effect modifiers in these analyses:age, sex, occupation, self-reported health status, physical activity, education, cigarette smoking, Khat use and alcohol consumption [35, 36]. All analyses were performed using STATA 11.0 statistical software for Windows (Statacorp, College Station, TX, USA). All reported p-values are two-sided and deemed statistically significant at α=0.05.

Results

A summary of selected socio-demographic and lifestyle characteristics of study participants is presented in Table 1. A total of 1,924 participants between the ages of 18 and 67 years (mean age=35 years, standard deviation=11 years) participated in the study. The majority of participants were men (60.6%), unmarried (51%) and more likely to have a college diploma, bachelor's degree, or higher education (70.7%). Approximately 7% of participants reported that they were heavy drinkers and 9% reported that they were current smokers. Khat consumption was reported by 8.8% of participants. Approximately 40% of participants reported having a fair or poor health status.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study population according to major depressive disorder status.

| Characteristic | All N=1,924 | Depression N=154 | No Depression N=1,770 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | P-value** | |

| Mean Age* | 35.9 ± 11.8 | 33.1 ± 10.9 | 36.1 ± 11.9 | |

| Sex | ||||

| Women | 759 (39.4) | 60 (39.0) | 699 (39.5) | 0.897 |

| Men | 1,165 (60.6) | 94 (61.0) | 1071 (60.5) | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18-29 | 799 (41.6) | 83 (54.3) | 716 (39.8) | 0.017 |

| 30-39 | 441 (22.9) | 32 (20.9) | 409 (23.6) | |

| 40-49 | 307 (16.0) | 17 (11.1) | 290 (16.5) | |

| 50-59 | 353 (18.4) | 20 (13.1) | 333 (18.9) | |

| ≥60 | 21 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) | 20 (1.2) | |

| Education | ||||

| ≤ High school | 564 (29.3) | 55 (35.7) | 509 (28.8) | 0.069 |

| ≥ College education | 1,360 (70.7) | 99 (64.3) | 1,261 (71.2) | |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never | 1,670 (86.8) | 126 (81.8) | 1,544 (87.2) | 0.153 |

| Former smoker | 84 (4.4) | 10 (6.5) | 74 (4.2) | |

| Current smoker | 170 (8.8) | 18 (11.7) | 152 (8.6) | |

| Alcohol consumption in past year | ||||

| Non drinker | 435 (22.6) | 25 (16.2) | 410 (23.2) | 0.032 |

| Moderate | 1,353 (70.3) | 112 (72.7) | 1,241 (70.1) | |

| Heavy | 136 (7.1) | 17 (11.1) | 119 (6.7) | |

| Khat use | ||||

| No | 1,758 (91.4) | 137 (89.0) | 1,621 (91.6) | 0.256 |

| Yes | 165 (8.6) | 17 (11.0) | 148 (8.4) | |

| Self-reported health status | ||||

| Excellent/very good/good | 1,161(60.3) | 61 (39.6) | 1,100 (62.2) | <0.001 |

| Poor/fair | 763 (39.7) | 93 (60.4) | 670 (37.8) | |

Mean ± standard deviation (SD);

P-value from Chi-Square test or Student's t test

Numbers/percentages may not add up to the total number due to missing data.

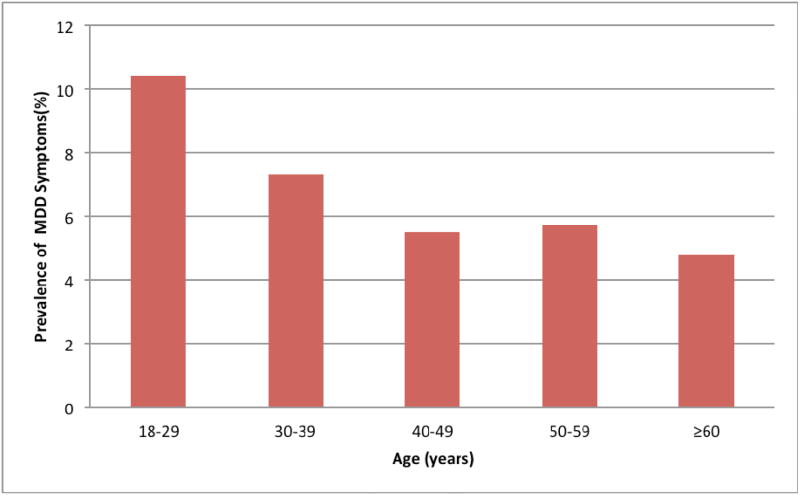

Distributions of the socio-demographic and lifestyle characteristics according to participants' depression status are also presented in Table 1. A total of 154 participants screened positive for MDD on PHQ-9 (8.0%; 95% CI 6.7-9.2). No significant difference in MDD prevalence was noted between men and women. Depressed participants were more likely to be younger, to have a lower level of educational attainment, to be heavy drinkers, and to report a poor health status. The prevalence of MDD according to age groups is presented in Figure 1. Depression prevalence varied with age with the highest being in early adult life (18-29 years), and declining thereafter.

Figure 1. Prevalence of MDD symptoms according age.

The prevalence of MDD varied with age with the highest being in early adult life (18-29 years), and declining thereafter.

As shown in Table 2, we calculated the odds ratio for diabetes and hypertension status in relation to MDD. Among women, MDD was associated with more than 4-fold increased odds of diabetes (OR =4.14; 95% CI: 1.03-16.62) after adjusting for confounders. Among men, we observed no evidence of an association of MDD with diabetes (OR=1.04; 95% CI: 0.35-3.05). After controlling for confounders, there was no clear evidence for a positive association between MDD and hypertension status in women (OR=1.05; 95% CI: 0.37-2.99) or men (OR=0.76; 95% CI: 0.37-1.57).

Table 2. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of diabetes status and hypertension status in relation to major depressive disorder among men and women.

| Normal Fasting Glucose | Impaired Fasting Glucose | Diabetes Mellitus | Normotensive | Hypertensive | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | |||||

| Unadjusted | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.05 (0.56-1.98) | 1.28 (0.37-4.37) | 1.0 (Reference) | 0.93 (0.38-2.25) |

| Model 1 | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.24 (0.66-2.37) | 2.77 (0.73-10.65) | 1.0 (Reference) | 0.94 (0.33-2.65 |

| Model 2 | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.35 (0.93-3.86) | 3.37 (0.86-13.22) | 1.0 (Reference) | 0.98 (0.35-2.77) |

| Model 3 | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.44 (0.74-2.78) | 4.14 (1.03-16.62) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.05 (0.37-2.99) |

| Men | |||||

| Unadjusted | 1.0 (Reference) | 0.92 (0.55-1.55) | 0.76 (0.27-2.16) | 1.0 (Reference) | 0.68 (0.35-1.32) |

| Model 1 | 1.0 (Reference) | 0.99 (0.58-1.67) | 0.93 (0.32-2.70) | 1.0 (Reference) | 0.75 (0.36-1.53) |

| Model 2 | 1.0 (Reference) | 0.94 (0.54-1.62) | 0.98 (0.33-2.89) | 1.0 (Reference) | 0.73 (0.35-1.47) |

| Model 3 | 1.0 (Reference) | 0.98 (0.57-1.71) | 1.04 (0.35-3.05) | 1.0 (Reference) | 0.76 (0.37-1.57) |

Model 1 (age and BMI): Adjusted for age and body mass index

Model 2 (lifestyle): Adjusted for age, Khat consumption, alcohol drinking, smoking and physical activity

Model 3 (fully adjusted): Adjusted for age, body mass index, occupation, Khat consumption, alcohol consumption, smoking and physical activity

As presented in Table 3, the odds of lipid abnormalities in relation to MDD were evaluated. After adjusting for possible confounding by age, alcohol consumption, Khat consumption, smoking status, body mass index, and occupation, there was no statistically significant association of MDD with lipid abnormalities.

Table 3. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of lipid abnormalities in relation to major depressive disorder among men and women.

| Lipids (mg/dL) | Women | Men | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted* OR (95% CI) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted* OR (95% CI) | |

| HDL-C | ||||

| Low (<40) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Normal (40-60) | 0.47 (0.18-1.18) | 0.54 (0.21-1.38) | 0.73 (0.42-1.30) | 0.69 (0.39-1.25) |

| High (≥ 60) | 0.67 (0.23-1.94) | 0.80 (0.26-2.41) | 0.45 (0.13-1.62) | 0.39 (0.11-1.41) |

| LDL-C | ||||

| Optimal (<100) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Above optimal (100-129) | 1.05 (0.56-1.96) | 1.25 (0.65-2.42) | 0.97 (0.60-1.59) | 1.01 (0.62-1.68) |

| High (>130) | 0.67 (0.33-1.36) | 0.94 (0.42-2.06) | 0.77 (0.45-1.33) | 0.84 (0.47-1.52) |

| TC | ||||

| Desirable (<200) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Borderline high (200-239) | 1.05 (0.58-1.88) | 1.27 (0.68-2.36) | 0.87 (0.51-1.48) | 0.86 (0.49-1.51) |

| High (≥ 240) | 0.36 (0.11-1.29) | 0.41 (0.09-1.84) | 0.62 (0.29-1.32) | 0.67 (0.31-1.50) |

| Triglycerides | ||||

| Normal(<150) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Borderline-high (150-199) | 0.85 (0.33-2.20) | 1.32 (0.48-3.61) | 1.01 (0.56-1.81) | 1.16 (0.61-2.19) |

| High (≥ 200) | 1.75 (0.66-4.67) | 3.08 (0.92-10.35) | 0.64 (0.33-1.24) | 0.70 (0.34-1.43) |

Adjusted for alcohol consumption, Khat consumption, smoking status, age, body mass index, occupation, and physical activity

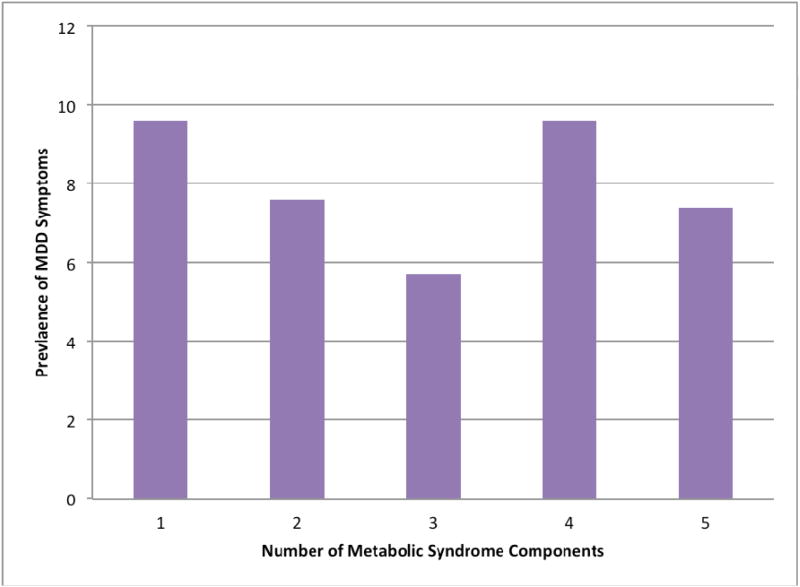

As shown in Table 4, there was no statistically significant association of MDD with metabolic syndrome among women (OR=1.51; 95% CI: 0.68-3.29) or men (OR=0.61; 95% CI: 0.28-1.34). In addition, there was no evidence of statistically significant associations of MDD with increasing number of MetS components (p for trend=0.189) (Figure 2). The odds of insulin resistance among women and men were (OR=2.89; 95% CI: 0.73-11.35) and (OR=0.66; 95% CI: 0.08-5.61), respectively. Lastly, MDD was not statistically significantly associated with the odds of chronic systemic inflammation as measured with high CRP concentrations among both women (OR=0.87; 95% CI: 0.12-1.49) and men (OR=1.51: 95% CI: 0.50-4.49).

Table 4. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of metabolic syndrome, C-reactive protein, and insulin resistance in relation to major depressive disorder among men and women – Nested case control (156 cases and 360 controls).

| All | Women | Men | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted* OR (95% CI) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted* OR (95% CI) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted** OR (95% CI) | |

| Metabolic Syndrome | ||||||

| No | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Yes | 0.70 (0.43-1.17) | 0.93 (0.52-1.64) | 0.54 (0.26-1.13) | 1.51 (0.68-3.29) | 1.24 (0.43-3.59) | 0.61 (0.28-1.34) |

| C-reactive Protein | ||||||

| Low | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| High | 0.71 (0.32-1.54) | 0.75 (0.34-1.66) | 0.41 (0.12-1.43) | 0.42 (0.12-1.49) | 1.24 (0.43-3.59) | 1.51 (0.50-4.49) |

| Insulin Resistance | ||||||

| No | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Yes | 1.13 (0.38-3.32) | 1.32 (0.43-3.99) | 2.58 (0.68-9.83) | 2.89 (0.73-11.35) | 0.45 (0.06-3.52) | 0.66 (0.08-5.61) |

Adjusted for age, work place, alcohol consumption, and physical activity

Adjusted for age, work place, BMI, Khat consumption, and physical activity

Figure 2. Prevalence of MDD symptoms according to number of MetS components.

There was no evidence of statistically significant associations of MDD with increasing number of MetS components (p for trend=0.189).

Discussion

Given the body of epidemiologic evidence showing that depression is associated with and increased risk of cardiometabolic disease, we expected that MDD would be associated with cardiometabolic disease risk factors. However, we found little evidence of such an association among Ethiopian adults after controlling for confounders. Specifically, MDD was not associated with increased odds of hypertension, metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance or inflammation. However, among women, MDD was associated with more than 4-fold increased odds of diabetes.

There is a growing body of epidemiologic evidence that shows MDD as risk factor for diabetes [19]. Our study results showing significant association between MDD and diabetes among women are in agreement with some prior studies although inferences from this analysis are limited by our relatively small size as reflected by the wide 95% CI. A longitudinal study conducted among participants in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) found that depressive symptoms at baseline were associated with an increased incidence of type 2 diabetes after adjusting for confounding factors. However, baseline impaired fasting glucose was associated with reduced risk of depression. Other investigators have reported that depression is a risk factor for diabetes. For instance, Carnethon et al [37] in their study among Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) participants found that older adults who reported higher depressive symptoms were more likely to develop diabetes than their counterparts. Wagner et al [38] also found higher HbA1c (marker of diabetes status) and more diabetes complications among African Americans with higher depressive symptoms after controlling for confounders. In the current study, similar increased odds in insulin resistance were observed for women, although statistical significance was not achieved. The lack of association observed in our study is, in part, due to small sample size as reflected by the wider 95% CIs. Collectively the results of our study and those of others underscore the importance of evaluating depression among diabetics as it is associated with poor diabetes outcomes such as glycemic control and need of insulin therapy [19].

In the current study, we found no evidence of an association between MDD and CRP after adjustment for possible confounders. There is an accumulating epidemiologic evidence suggesting an association between depression and elevated levels of inflammatory markers such as CRP [15, 39-42]. For instance, Ford et al using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) reported that MDD was strongly associated with increased CRP concentrations among men (OR=3.00;95% CI: 1.39-6.48). There was, however, no evidence of an association of elevated CRP concentrations and depression among women [43]. Similar observation was noted by Danner et al using NHANES data [44]. Others have also noted that depression was independently associated with elevated CRP concentrations [45, 46]. Recently Wium-Andersen et al in Denmark using population based studies noted that elevated levels of CRP were associated with increased risk of depression in the general population[47]. On the other hand, Tiemeier et al [17] in their population-based Rotterdam Study found no significant association between depression and CRP after multivariate adjustment. Although available evidence suggests an association between depression and inflammation, it remains unclear whether the inflammation seen in depressed patients is a result of stress response or whether cardiometabolic disease risk related inflammation contributes to the pathogenesis of depression.

Most investigators, though not all, have shown previously that a bi-directional association between depression and hypertension in the US and European populations [48]. Very little is known, however, about this association among sub-Saharan Africans. To the best of our knowledge, to date, only one group of investigators has evaluated the relationship. Using a nationally representative sample from South Africa, as part of the World Mental Health Survey, Grimsrud et al found that MDD was not associated with previous medical diagnosis of hypertension [18]. Our study results documenting lack of association between MDD and hypertension are in agreement with their finding. Notably, the South African study [18] showed that anxiety disorders were associated with hypertension status. Perhaps, future studies among sub-Saharan Africans that evaluate other comorbid psychiatric disorders and with longitudinal cardiometabolic disease risk measures might shed light on this issue.

Similarly, we found no evidence of associations of MDD with lipid abnormalities. Some investigators have shown that total cholesterol, in particular, low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol is associated with increased risks of depression; while high density lipoprotein is inversely related to depressive symptoms [49]. This finding is however in contrast with other reports. Tedders et al [50] using the NHANES survey reported no significant association between depression and lipid concentrations. However, the authors noted a U shaped association between LDL and depression among men [50].

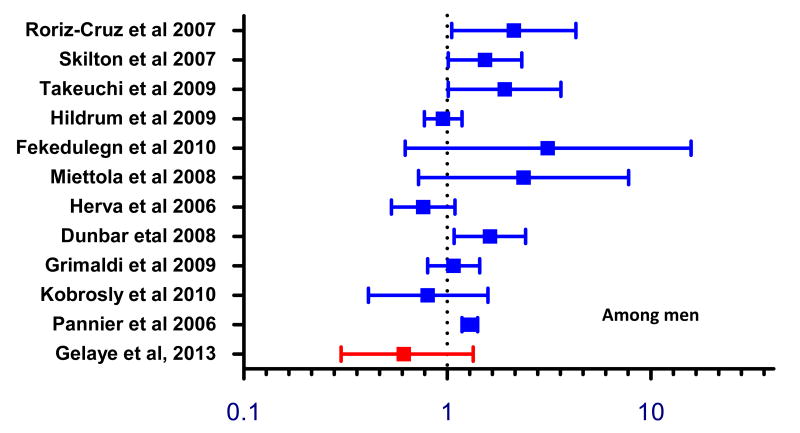

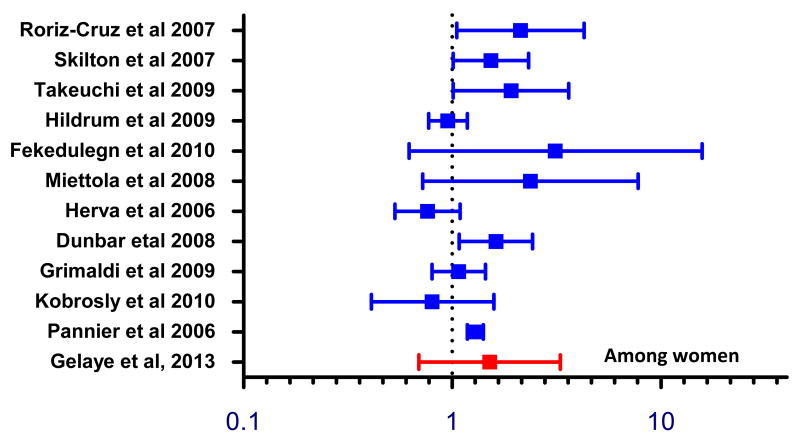

The relationship between MDD and metabolic syndrome has been widely studied. However, results have been inconclusive, and few studies have examined sub-Saharan African population [48, 51-53]. Our study results are consistent with some prior studies that showed no significant association between depression and metabolic syndrome (Figures 3 and 4) [51, 53]. Our results, however, are not in agreement with findings from studies by other investigators (Figures 3 and 4) [54-66]. Recently, a meta-analysis conducted by Pan et al [52] reviewed cohort and cross-sectional studies that examined the association between depression and metabolic syndrome. Within cohort studies, the authors noted a bi-directional relationship where the pooled adjusted OR among studies that used depression as the outcome was (OR= 1.49; 95% CI: 1.19–1.87) and among studies that used metabolic syndrome as an outcome (OR=1.52; 95% CI: 1.20–1.91]. Similar bi-directional associations were found in cross-sectional studies. The lack of association observed in most of the prior studies, in part, may be due to small sample size. Our findings documenting gender difference in the magnitude of association between MDD and metabolic syndrome are in agreement with those reported by others. We do not have clear explanation for these findings but we speculate that difference in physical activity and other lifestyle characteristics might have contributed to the observed differences[67]. It is also possible that that there could be underlying biological differences in metabolic syndrome risk among men and women that requires further study [68].

Figure 3. Forest plot of cross-sectional studies evaluating the odds of metabolic syndrome in relation to depression.

Figure 4. Forest plot of cross-sectional studies evaluating the odds of metabolic syndrome in relation to depression.

Among women, the magnitude and direction of associations between metabolic syndrome and depression was largely similar to prior studies.

The biological mechanisms linking depression and cardiometabolic disease risk are plausible but not fully established. Most investigators have suggested that alterations in the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis might be playing an important role in the pathophysiology of depression and cardiometabolic metabolic disease [69]. A large proportion of depressed subjects have autonomic imbalance characterized by increased sympathetic activation, decreased vagal tone, and abnormal HPA activity [12, 42, 70, 71]. In addition activation of the HPA axis results in increased secretion of corticotrophin-releasing factor (CRF) [15] resulting in excess cortisol secretion. Cortisol is a counter-regulatory hormone known to be associated with type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension [11, 13]. There is also an expanding literature suggesting endothelial dysfunction as a potential link between cardiometabolic disease risk and depression [14, 72]. Finally, some investigators have speculated that depression may be associated with unhealthy lifestyle habits, such as smoking, non-compliance with medical recommendation, unhealthy diet, and physical inactivity, which in turn increase the risk of cardiometabolic disease [73]. While conclusive answers about the mechanistic link between cardiometabolic disease risk and depression remain elusive, an increasing body of research has begun to shed light on these important topics. Clearly, however, future research is needed to more definitively establish a causal link and to help understand the role of depression in the pathogenesis of cardiometabolic disease.

The results of the current study have several potential limitations that bear on the interpretation of the study findings. First, our analyses are based on cross-sectionally collected data which leaves ambiguity concerning the temporal relation between depression and cardiometabolic disease. Longitudinal studies are needed to examine the temporal association between depression and cardiometabolic disease risk. Second, although we adjusted for several potential confounders, we cannot exclude the possibility of residual confounding due to misclassification of adjusted variables or confounding by other unmeasured variables. Third, the classification of MDD was done using the PHQ-9 questionnaire that does not give definitive clinical diagnosis of depression. However, use of validated instruments such as PHQ-9 remains the most feasible method of data collection for large-scale epidemiological studies[74]. Fourth, given the imperfect sensitivity and specificity of PHQ-9 in our study, there is a possibility of misclassification of MDD. The impact of this non-differential misclassification would generally underestimate the true magnitude of associations detected in our study[75]. Findings from other studies that used screening and diagnostic instruments with better psychometric properties attenuate concerns about misclassification of MDD status. Fifth, though we consider it very unlikely, we cannot rule out the possibility of missing weaker associations or association that may only be present among sub-specific subject groups. However the consistencies of our findings with prior studies, in part, provide some assurance that misclassification and other biases are probably not responsible for the observed association. Finally, our study findings may not be generalized to the broader Ethiopian population since our study was limited to a largely well-educated, urban dwelling, occupational cohort comprised of white-collar professionals in banking and academic sectors. The concordance of our results with those from other studies that have included various socio-economic status and geographically diverse populations, however, serve to attenuate some concerns about the generalizability of our findings.

In conclusion, our study results do not provide convincing evidence of associations of MDD with cardiometabolic disease among Ethiopian adults. Future studies need to evaluate the associations of other psychiatric disorders on cardiometabolic risk and shed further light on these relationships among sub-Saharan Africans.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by an award from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities (T37-MD001449). The authors wish to thank the staff of Addis Continental Institute of Public Health for their expert technical assistance. The authors would also like to thank the participants in the study, the Commercial Bank of Ethiopia and the Addis Ababa Education Office for granting access to conduct the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Reddy K, Yusuf S. Emerging epidemic of cardiovascular disease in developing countries. Circulation. 1998;97(6):596–601. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.6.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Njelekela MA, Mpembeni R, Muhihi A, Mligiliche NL, Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E, Liu E, Finkelstein JL, Fawzi WW, Willett WC, et al. Gender-related differences in the prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors and their correlates in urban Tanzania. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2009;9:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-9-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oladapo OO, Salako L, Sodiq O, Shoyinka K, Adedapo K, Falase AO. A prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors among a rural Yoruba south-western Nigerian population: a population-based survey. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2010;21(1):26–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tesfaye F, Byass P, Wall S. Population based prevalence of high blood pressure among adults in Addis Ababa: uncovering a silent epidemic. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2009;9:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-9-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tran A, Gelaye B, Girma B, Lemma S, Berhane Y, Bekele T, Khali A, Williams MA. Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome among Working Adults in Ethiopia. Int J Hypertens. 2011;2011:193719. doi: 10.4061/2011/193719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wai WS, Dhami RS, Gelaye B, Girma B, Lemma S, Berhane Y, Bekele T, Khali A, Williams MA. Comparison of measures of adiposity in identifying cardiovascular disease risk among Ethiopian adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20(9):1887–1895. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Muntner P, Whelton PK, He J. Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet. 2005;365(9455):217–223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17741-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roglic G, Unwin N, Bennett PH, Mathers C, Tuomilehto J, Nag S, Connolly V, King H. The burden of mortality attributable to diabetes: realistic estimates for the year 2000. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(9):2130–2135. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.9.2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomlinson M, Swartz L, Kruger LM, Gureje O. Manifestations of affective disturbance in sub-Saharan Africa: key themes. J Affect Disord. 2007;102(1-3):191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kinder LS, Carnethon MR, Palaniappan LP, King AC, Fortmann SP. Depression and the metabolic syndrome in young adults: findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(3):316–322. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000124755.91880.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katon W, Maj M, Sartorius N. Depression and diabetes Chichester. West Sussex; Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carney RM, Freedland KE, Sheline YI, Weiss ES. Depression and coronary heart disease: a review for cardiologists. Clin Cardiol. 1997;20(3):196–200. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960200304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Celano CM, Huffman JC. Depression and cardiac disease: a review. Cardiol Rev. 2011;19(3):130–142. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e31820e8106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glassman AH, Maj M, Sartorius N. Depression and heart disease Chichester. West Sussex; Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carney RM, Freedland KE, Miller GE, Jaffe AS. Depression as a risk factor for cardiac mortality and morbidity: a review of potential mechanisms. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(4):897–902. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foley DL, Morley KI, Madden PA, Heath AC, Whitfield JB, Martin NG. Major depression and the metabolic syndrome. Twin research and human genetics : the official journal of the International Society for Twin Studies. 2010;13(4):347–358. doi: 10.1375/twin.13.4.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tiemeier H, Hofman A, van Tuijl HR, Kiliaan AJ, Meijer J, Breteler MM. Inflammatory proteins and depression in the elderly. Epidemiology. 2003;14(1):103–107. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200301000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grimsrud A, Stein DJ, Seedat S, Williams D, Myer L. The association between hypertension and depression and anxiety disorders: results from a nationally-representative sample of South African adults. PloS one. 2009;4(5):e5552. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katon WJ. The comorbidity of diabetes mellitus and depression. The American journal of medicine. 2008;121(11 Suppl 2):S8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization. Primary Health Care Management of Trachoma. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 21.WHO. STEPs manual. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Belew M, Kebede D, Kassaye M, Enquoselassie F. The magnitude of khat use and its association with health, nutrition and socio-economic status. Ethiop Med J. 2000;38(1):11–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalix P. Khat: scientific knowledge and policy issues. Br J Addict. 1987;82(1):47–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1987.tb01436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wai WS, Dhami RS, Gelaye B, Girma B, Lemma S, Berhane Y, Bekele T, Khali A, Williams MA. Comparison of Measures of Adiposity in Identifying Cardiovascular Disease Risk Among Ethiopian Adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011 doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J. Metabolic syndrome--a new world-wide definition. A Consensus Statement from the International Diabetes Federation. Diabet Med. 2006;23(5):469–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Expert Panel on Detection E, Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in A. Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285(19):2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28(7):412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deveci E, Yesil M, Akinci B, Yesil S, Postaci N, Arikan E, Koseoglu M. Evaluation of insulin resistance in normoglycemic patients with coronary artery disease. Clin Cardiol. 2009;32(1):32–36. doi: 10.1002/clc.20379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hillman AJ, Lohsoonthorn V, Hanvivatvong O, Jiamjarasrangsi W, Lertmaharit S, Williams MA. Association of High Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein Concentrations and Metabolic Syndrome among Thai Adults. Asian biomedicine : research, reviews and news. 2010;4(3):385–393. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang FY, Chung H, Kroenke K, Delucchi KL, Spitzer RL. Using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 to measure depression among racially and ethnically diverse primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(6):547–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lichtman JH, Bigger JT, Jr, Blumenthal JA, Frasure-Smith N, Kaufmann PG, Lesperance F, Mark DB, Sheps DS, Taylor CB, Froelicher ES. Depression and coronary heart disease: recommendations for screening, referral, and treatment: a science advisory from the American Heart Association Prevention Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research: endorsed by the American Psychiatric Association. Circulation. 2008;118(17):1768–1775. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.190769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gelaye B, Williams MA, Lemma S, Deyessa N, Bahretibeb Y, Shibre T, Wondimagegn D, Lemenhe A, Fann JR, Vander Stoep A, et al. Validity of the patient health questionnaire-9 for depression screening and diagnosis in East Africa. Psychiatry research. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.WHO. Global status report on alcohol. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Modern epidemiology. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alem A, Kebede D, Woldesemiat G, Jacobsson L, Kullgren G. The prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of mental distress in Butajira, Ethiopia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1999;397:48–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb10694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gelaye B, Lemma S, Deyassa N, Bahretibeb Y, Tesfaye M, Berhane Y, Williams MA. Prevalence and correlates of mental distress among working adults in ethiopia. Clinical practice and epidemiology in mental health : CP & EMH. 2012;8:126–133. doi: 10.2174/1745017901208010126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carnethon MR, Biggs ML, Barzilay JI, Smith NL, Vaccarino V, Bertoni AG, Arnold A, Siscovick D. Longitudinal association between depressive symptoms and incident type 2 diabetes mellitus in older adults: the cardiovascular health study. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(8):802–807. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.8.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wagner JA, Abbott GL, Heapy A, Yong L. Depressive symptoms and diabetes control in African Americans. Journal of immigrant and minority health/Center for Minority Public Health. 2009;11(1):66–70. doi: 10.1007/s10903-008-9147-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith PJ, Blumenthal JA. Psychiatric and Behavioral Aspects of Cardiovascular Disease: Epidemiology, Mechanisms, and Treatment. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.recesp.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blumberger DM, Daskalakis ZJ, Mulsant BH. Biomarkers in geriatric psychiatry: searching for the holy grail? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21(6):533–539. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328314b763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Howren MB, Lamkin DM, Suls J. Associations of depression with C-reactive protein, IL-1, and IL-6: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2009;71(2):171–186. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181907c1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F, Irwin MR, Talajic M, Pollock BG. The relationships among heart rate variability, inflammatory markers and depression in coronary heart disease patients. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23(8):1140–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ford DE, Erlinger TP. Depression and C-reactive protein in US adults: data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(9):1010–1014. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.9.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Danner M, Kasl SV, Abramson JL, Vaccarino V. Association between depression and elevated C-reactive protein. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(3):347–356. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000041542.29808.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C, Chrysohoou C, Tsetsekou E, Papageorgiou C, Christodoulou G, Stefanadis C, study A. Inflammation, coagulation, and depressive symptomatology in cardiovascular disease-free people; the ATTICA study. European heart journal. 2004;25(6):492–499. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kop WJ, Gottdiener JS, Tangen CM, Fried LP, McBurnie MA, Walston J, Newman A, Hirsch C, Tracy RP. Inflammation and coagulation factors in persons > 65 years of age with symptoms of depression but without evidence of myocardial ischemia. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89(4):419–424. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)02264-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wium-Andersen MK, Orsted DD, Nielsen SF, Nordestgaard BG. Elevated C-reactive protein levels, psychological distress, and depression in 73 131 individuals. JAMA psychiatry. 2013;70(2):176–184. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meng L, Chen D, Yang Y, Zheng Y, Hui R. Depression increases the risk of hypertension incidence: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Journal of hypertension. 2012;30(5):842–851. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32835080b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Manfredini R, Caracciolo S, Salmi R, Boari B, Tomelli A, Gallerani M. The association of low serum cholesterol with depression and suicidal behaviours: new hypotheses for the missing link. The Journal of international medical research. 2000;28(6):247–257. doi: 10.1177/147323000002800601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tedders SH, Fokong KD, McKenzie LE, Wesley C, Yu L, Zhang J. Low cholesterol is associated with depression among US household population. J Affect Disord. 2011;135(1-3):115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pulkki-Raback L, Elovainio M, Kivimaki M, Mattsson N, Raitakari OT, Puttonen S, Marniemi J, Viikari JS, Keltikangas-Jarvinen L. Depressive symptoms and the metabolic syndrome in childhood and adulthood: a prospective cohort study. Health Psychol. 2009;28(1):108–116. doi: 10.1037/a0012646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pan A, Keum N, Okereke OI, Sun Q, Kivimaki M, Rubin RR, Hu FB. Bidirectional association between depression and metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(5):1171–1180. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vogelzangs N, Beekman AT, Boelhouwer IG, Bandinelli S, Milaneschi Y, Ferrucci L, Penninx BW. Metabolic depression: a chronic depressive subtype? Findings from the InCHIANTI study of older persons. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(5):598–604. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mast BT, Miles T, Penninx BW, Yaffe K, Rosano C, Satterfield S, Ayonayon HN, Harris T, Simonsick EM. Vascular disease and future risk of depressive symptomatology in older adults: findings from the Health, Aging, and Body Composition study. Biological psychiatry. 2008;64(4):320–326. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Almeida OP, Calver J, Jamrozik K, Hankey GJ, Flicker L. Obesity and metabolic syndrome increase the risk of incident depression in older men: the health in men study. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry : official journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. 2009;17(10):889–898. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181b047e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dunbar JA, Reddy P, Davis-Lameloise N, Philpot B, Laatikainen T, Kilkkinen A, Bunker SJ, Best JD, Vartiainen E, Kai Lo S, et al. Depression: an important comorbidity with metabolic syndrome in a general population. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(12):2368–2373. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fekedulegn D, Andrew M, Violanti J, Hartley T, Charles L, Burchfiel C. Comparison of statistical approaches to evaluate factors associated with metabolic syndrome. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2010;12(5):365–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2010.00264.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grimaldi S, Englund A, Partonen T, Haukka J, Pirkola S, Reunanen A, Aromaa A, Lonnqvist J. Experienced poor lighting contributes to the seasonal fluctuations in weight and appetite that relate to the metabolic syndrome. Journal of environmental and public health. 2009;2009:165013. doi: 10.1155/2009/165013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Herva A, Rasanen P, Miettunen J, Timonen M, Laksy K, Veijola J, Laitinen J, Ruokonen A, Joukamaa M. Co-occurrence of metabolic syndrome with depression and anxiety in young adults: the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort Study. Psychosom Med. 2006;68(2):213–216. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000203172.02305.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hildrum B, Mykletun A, Midthjell K, Ismail K, Dahl AA. No association of depression and anxiety with the metabolic syndrome: the Norwegian HUNT study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;120(1):14–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kobrosly RW, van Wijngaarden E. Revisiting the association between metabolic syndrome and depressive symptoms. Annals of epidemiology. 2010;20(11):852–855. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miettola J, Niskanen LK, Viinamaki H, Kumpusalo E. Metabolic syndrome is associated with self-perceived depression. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2008;26(4):203–210. doi: 10.1080/02813430802117624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pannier B, Thomas F, Eschwege E, Bean K, Benetos A, Leocmach Y, Danchin N, Guize L. Cardiovascular risk markers associated with the metabolic syndrome in a large French population: the “SYMFONIE” study. Diabetes & metabolism. 2006;32(5 Pt 1):467–474. doi: 10.1016/s1262-3636(07)70305-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roriz-Cruz M, Rosset I, Wada T, Sakagami T, Ishine M, Roriz-Filho JS, Cruz TR, Rodrigues RP, Resmini I, Sudoh S, et al. Stroke-independent association between metabolic syndrome and functional dependence, depression, and low quality of life in elderly community-dwelling Brazilian people. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2007;55(3):374–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Skilton MR, Moulin P, Terra JL, Bonnet F. Associations between anxiety, depression, and the metabolic syndrome. Biological psychiatry. 2007;62(11):1251–1257. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Takeuchi T, Nakao M, Nomura K, Yano E. Association of metabolic syndrome with depression and anxiety in Japanese men. Diabetes & metabolism. 2009;35(1):32–36. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Workalemahu T, Gelaye B, Berhane Y, Williams MA. Physical Activity and Metabolic Syndrome among Ethiopian Adults. American journal of hypertension. 2013 doi: 10.1093/ajh/hps079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Muhtz C, Zyriax BC, Klahn T, Windler E, Otte C. Depressive symptoms and metabolic risk: effects of cortisol and gender. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(7):1004–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Grippo AJ, Johnson AK. Biological mechanisms in the relationship between depression and heart disease. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2002;26(8):941–962. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Esler M, Turbott J, Schwarz R, Leonard P, Bobik A, Skews H, Jackman G. The peripheral kinetics of norepinephrine in depressive illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39(3):295–300. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290030035006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Siever LJ, Davis KL. Overview: toward a dysregulation hypothesis of depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(9):1017–1031. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.9.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pariante CM. Understanding depression : a translational approach. London; New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Empana JP, Jouven X, Lemaitre RN, Sotoodehnia N, Rea T, Raghunathan TE, Simon G, Siscovick DS. Clinical depression and risk of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(2):195–200. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gelaye B, Peterlin BL, Lemma S, Tesfaye M, Berhane Y, Williams MA. Migraine and Psychiatric Comorbidities Among Sub-Saharan African Adults. Headache. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2012.02259.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.White E, Armstrong BK, Saracci R, Armstrong BK. Principles of exposure measurement in epidemiology : collecting, evaluating, and improving measures of disease risk factors. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]