Abstract

AIM: To investigate the epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection among the healthy asymptomatic population in Iran and countries of the Eastern Mediterranean Region.

METHODS: A computerized English language literature search of PubMed, ISI Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar was performed in September 2013. The terms, “Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office (EMRO)” and “Helicobacter pylori”, “H. pylori” and “prevalence” were used as key words in titles and/or abstracts. A complementary literature search was also performed in the following countries: Afghanistan, Bahrain, Djibouti, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Oman, Pakistan, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, The United Arab Emirates, and Yemen.

RESULTS: In the electronic search, a total of 308 articles were initially identified. Of these articles, 26 relevant articles were identified and included in the study. There were 10 studies from Iran, 5 studies from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 4 studies from Egypt, 2 from the United Arab Emirates, and one study from Libya, Oman, Tunisia, and Lebanon, respectively. The overall prevalence of H. pylori infection in Iran, irrespective of time and age group, ranged from 30.6% to 82%. The overall prevalence of H. pylori infection, irrespective of time and age group, in other EMRO countries ranged from 22% to 87.6%.

CONCLUSION: The prevalence of H. pylori in EMRO countries is still high in the healthy asymptomatic population. Strategies to improve sanitary facilities, educational status, and socioeconomic status should be implemented to minimize H. pylori infection.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Prevalence, Epidemiology, Iran, Eastern Mediterranean Region Office

Core tip: Countries in the World Health Organization, Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office include a group of developing countries located in the southwest and west of Asia as well as North Africa. Understanding the epidemiological aspects of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is important and helpful in clarifying the consequences and complications of infection. There are no systematic reviews on the prevalence and epidemiology of H. pylori in this geographically important region of the world. The aim of this study was to perform a comprehensive review of the epidemiology of H. pylori infection in this area.

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a gram negative, non-spore forming spiral bacterium which colonizes the human stomach and is prevalent worldwide[1]. It has been associated with peptic ulcer disease, gastric adenocarcinoma, and type B low-grade mucosal-associated lymphoma[2]. Furthermore, the organism is also thought to be involved in other human illnesses such as hematologic and autoimmune disorders, insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome[3-5]. Although nearly 50% of the population is infected with H. pylori worldwide, the prevalence, incidence, age distribution and sequels of infection are significantly different in developed and developing countries[6]. The prevalence of H. pylori infection is decreasing in both developed and developing countries; however, the prevalence is still high in developing countries[6]. In Argentina, the prevalence of a positive urea breath test (UBT) declined from 41.2% during 2002-2004 to 26% during 2007-2009 among children[7]. Furthermore, the age of developing the infection is lower in developing countries compared with industrialized nations[6]. It has been estimated that more than 50% of the population aged 5 years is infected and this rate may exceed 90% during adulthood[8]. In a cohort of Brazilian children, the prevalence of H. pylori was 53.4% at baseline and 64.7% 8 years later[9].

Understanding the epidemiological aspects of H. pylori infection is important and helpful in clarifying the consequences and complications of the infection, and is fundamental for eradication, treatment, and the pattern of antibiotic resistance. Countries in the World Health Organization, Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office (EMRO) include a group of developing countries located in southwest and western Asia as well as North Africa[10]. Economically heterogenous nations ranging from rich oil producing countries to poor countries are included in this group of countries. The ancient land of Iran is also located in this region. There are no systematic reviews on the prevalence and epidemiology of H. pylori in this geographically important region of the world. The aim of this study was to perform a comprehensive review of the epidemiology of H. pylori infection in this area.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was conducted according to the PRISMA (Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analyses) guidelines, flow diagram and checklist[11]. A computerized English language literature search of PubMed, ISI Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar was performed in September 2013. No time limitation was applied and studies on animal models were excluded. After a preliminary search of the MeSH database, search terms were selected. The terms, “EMRO” and “Helicobacter pylori”, “H. pylori” and “prevalence” were used as key words in titles and/or abstracts. A complementary literature search was also performed in the following countries: Afghanistan, Bahrain, Djibouti, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Oman, Pakistan, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, The United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Yemen.

Eligibility and critical appraisal of the studies

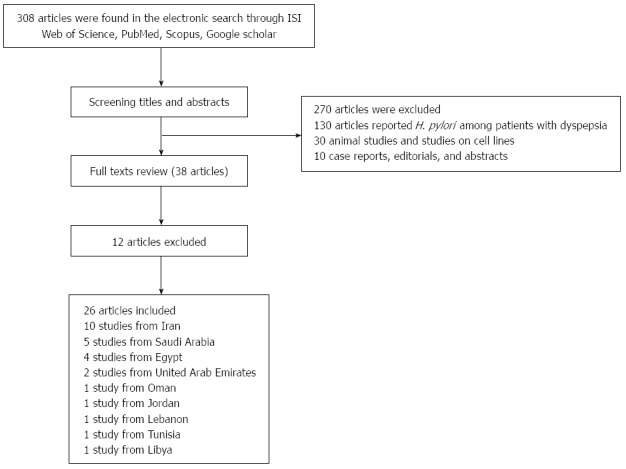

All the studies were reviewed and carefully appraised for inclusion in the study. All descriptive/analytical cross-sectional, case-control, and epidemiological studies, as well as cohort studies with appropriate methods were included. H. pylori was detected using anti-IgG H. pylori, the UBT, stool antigen, saliva anti-IgG H. pylori or endoscopy. Editorials, case reports, letters to the editor, hypotheses, studies on animals or cell lines, abstracts from conferences and unpublished reports were excluded. Studies were eligible for review if they reported H. pylori epidemiology in asymptomatic healthy individuals. Therefore, studies reporting the prevalence of H. pylori in patients with dyspepsia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, gastric or duodenal ulcer, gastritis, esophagitis, and gastric and esophageal cancer were excluded (Figure 1). Studies on pediatric subjects (age < 18 years) were also included.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study. H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori.

Data extraction

Data were abstracted from the full texts of relevant articles. Relevant data from articles reporting the prevalence of H. pylori and its epidemiology in Iran and other countries of the EMRO were extracted. Data on the number and sex of participants in each eligible study, study country (including city for Iran), prevalence of H. pylori infection, method of H. pylori detection, population age group, year of study, and risk factors were collected and classified in separate tables.

RESULTS

In the electronic search, a total of 308 articles were initially identified. After a review of titles/ abstracts and assessment of the relevance and validity of papers, studies with other determinants, those not related to our aims, case reports, animal studies, editorials, papers from other regions, and overlapping studies, 270 articles in total, were excluded. Based on the full text review of 38 papers, another 12 papers were excluded. Thus, 26 relevant articles were included in the review and data were abstracted and categorized into subsections. The detailed search strategy and results of the search for eligible studies are outlined in Figure 1. There were 10 relevant studies from Iran and 16 other studies from Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan, United Arab Emirates, Tunisia and Libya. Unfortunately, there were no relevant studies from Afghanistan, Bahrain, Djibouti, Iraq, Kuwait, Morocco, Pakistan, Palestine, Qatar, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen on the prevalence of H. pylori in healthy populations.

Prevalence and risk factors of H. pylori infection in Iran

In total, 10 relevant articles from different geographical areas in Iran were included. Seven studies used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay IgG-Ab for detection of H. pylori and 3 studies used stool antigen. There were 8459 participants in these 10 studies (3575 males and 4172 females; one study did not report gender). The age of the patients ranged from 4 mo to 83 years. These studies were conducted from 1997 to 2010. The overall prevalence of H. pylori infection, irrespective of time and age group, ranged from 30.6% to 82%. The prevalence of Anti-Cag A positivity was reported in 3 studies, and ranged from 57.7% to 72.8% (Table 1). The results regarding risk factors were conflicting; however, higher age, female sex, larger family size, source of water supply, level of education and hygiene practice were associated with H. pylori infection in different populations. Interestingly, residing in urban or rural areas was not among the independent risk factors for H. pylori infection, while anti-Cag A positivity was reported to increase with increasing age and in male gender, and this was higher in subjects aged < 30 years in one study (Table 2).

Table 1.

Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in the Iranian population

| Ref. | Year | Location | Age group | Number (M/F) | Prevalence | Prevalence (%) (M/F) | Method of detection |

| Alborzi et al[12] | 2005 | Shiraz (Southern Iran) | 8 mo-15 yr | 593 (308/284) | 82.0% | 81/83 | Stool antigen |

| Nouraie et al[13] | 2009 | Tehran | 18-65 yr | 2326 (968/1358) | 69.0% | 67.6/70.0 | ELISA IgG-Ab |

| Jafarzadeh et al[14] | 2005 | Rafsanjan (Southeast Iran) | 1-15 yr | 386 (187/199) | 46.6% | 51.9/41.7 | ELISA IgG-Ab |

| Jafarzadeh et al[15] | 2005 | Rafsanjan (Southeast Iran) | 20-60 yr | 200 (114/86) | 67.5% | 71.9/61.6 | ELISA IgG-Ab |

| Alizadeh et al[16] | 2003 | Nahavand (Western Iran) | ≥ 6 yr | 1518 (653/865) | 70.6% | 66.6/73.4 | ELISA IgG-Ab |

| Ghasemi Kebria et al[17] | 2010 | Golestan province (Northeast Iran) | 1-83 yr | 1028 (489/539) | 66.4% | 66.3/66.6 | ELISA IgG-Ab |

| Jafar et al[18] | 2007 | Sanandaj (Western Iran) | 4 mo-15 yr | 458 (231/227) | 64.2% | 65/63 | Stool antigen |

| Mikaeli et al[19] | 1997 | Ardebil and Yazd (Northwest and Central Iran) | < 20 yr | 711 (NA) | 47.5% (Ardebil) | NA | ELISA IgG-Ab |

| 30.6% (Yazd) | |||||||

| Mansour-Ghanaei et al[20] | 2007 | Rasht (Northern Iran) | 7-11 yr | 961 (475/486) | 40.0% | 49.7/50.3 | Stool antigen |

| Mahram et al[21] | 2004 | Zanjan (Western Iran) | 7-9 yr | 278 (150/128) | 52.8% | 56.0/50.7 | ELISA IgG-Ab |

M: Male; F: Female; ELISA: Enzyme- linked immunosorbent assay; Ab: Antibody; NA: Not available.

Table 2.

Risk factors for Helicobacter pylori infection and prevalence of Anti-Cag A seropositivity in the Iranian population

| Ref. | Prevalence of Anti-Cag A | Main findings and risk factors |

| Alborzi et al[12] | NA | The prevalence of H. pylori was significantly lower in the 15-yr-old age group compared to the < 14-yr-old age group |

| Sex was not a risk factor for prevalence | ||

| Nouraie et al[13] | NA | Higher maternal education was protective against H. pylori infection |

| Low education, increasing age and overcrowding were risk factors for H. pylori infection | ||

| Jafarzadeh et al[14] | 72.8% | Prevalence of Anti-Hp IgG and Anti-Cag A Ab were increased with age |

| Jafarzadeh et al[15] | 67.4% | Prevalence of Anti-Cag A Ab was higher in males than females |

| Prevalence of Anti-Cag A Ab was higher in those < 30 yr | ||

| Alizadeh et al[16] | NA | Female sex and age (median 37 yr) were risk factors for H. pylori infection |

| Hygienic practice and crowding were not risk factors for H. pylori infection | ||

| Ghasemi Kebria et al[17] | 57.7% | No significant difference between rural and urban areas regarding prevalence |

| Seroprevalence increased with increasing age | ||

| Jafar et al[18] | NA | Larger family size was associated with higher prevalence |

| Increasing age was associated with H. pylori infection | ||

| Mikaeli et al[19] | NA | Increasing age was the only predictor of H. pylori infection |

| Mansour-Ghanaei et al[20] | NA | Water supply was a predictor of H. pylori infection |

| Mahram et al[21] | NA | Age and sex were not risk factors for H. pylori infection |

NA: Not available; H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori.

Prevalence and risk factors of H. pylori infection in other countries of the Eastern Mediterranean region

There were 16 studies from other countries in the eastern Mediterranean region: Saudi Arabia (5 studies), Egypt (4 studies), Jordan (1 study), Libya (1 study), UAE (2 studies), Tunisia (1 study), Lebanon (1 study) and Oman (1 study). Of these, (ELISA) IgG-Ab was used for the detection of H. pylori in 13 studies. One study from Lebanon used stool antigen and one study form Saudi Arabia used saliva IgG-Ab for the detection of H. pylori infection. In total, 5233 participants were included in these 16 studies. These studies were conducted between 1989 and 2013 among individuals aged 1 mo to 97 years. The overall prevalence of H. pylori infection, irrespective of time and age group, ranged from 22% to 87.6%. Living in rural areas, poor sanitation, overcrowding, lower educational level, and low socioeconomic status were independent risk factors for H. pylori infection in different countries of the EMRO (Table 3).

Table 3.

Prevalence and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection in the healthy population of Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office countries

| Ref. | Year | Country | Age group | Number | Prevalence | Method of detection | Risk factors |

| Bani-Hani et al[22] | 2006 | Jordan | 1-9 yr | 200 | 55.5% | ELISA IgG-Ab | Living in rural areas, poor sanitation, overcrowding, low maternal educational level, low socioeconomic status |

| Naous et al[23] | 2007 | Lebanon | 1 mo-17 yr | 414 | 21.0% | Stool antigen | Low socioeconomic status, overcrowded houses, lower family income and poor parental education |

| Bakka et al[24] | 2002 | Libya | 1- > 70 yr | 360 | 76.0% | ELISA IgG-Ab | Low socioeconomic status, low educational level |

| Mansour et al[25] | 2010 | Tunisia | Any age | 250 | 64.0% | ELISA IgG-Ab | NA |

| Bener et al[26] | 2000 | UAE | Any age | 223 | 78.4% | ELISA IgG-Ab | NA |

| Bener et al[27] | 2006 | UAE | Any age | 151 | 74.1% | ELISA IgG-Ab | Unavailable drinking water, low educational level, long working duration, BMI > 25, housing conditions |

| Salem et al[28] | 1993 | Egypt | < 30 yr | 89 | 87.6% | ELISA IgG-Ab | NA |

| Mohammad et al[29] | 2007 | Egypt | 6-15 yr | 286 | 72.38% | UBT | Low socioeconomic status, low body weight and height, living in rural areas |

| Naficy et al[30] | 1997 | Egypt | < 36 mo | 187 | 10.0% | ELISA IgG-Ab | Only age (6-17 mo) |

| Bassily et al[31] | 1992 | Egypt | 17-42 yr | 169 | 88.0% | ELISA IgG-Ab | Lower level of education |

| Al Faleh et al[32] | 2007 | KSA | 16-18 yr | 1200 | 47.0% | ELISA IgG-Ab | Being female |

| Residing in Medina region | |||||||

| Hanafi et al[33] | 2012 | KSA | Any age | 456 | 28.3% | ELISA IgG-Ab | Rural residence, crowded housing, low socioeconomic status, use of tanks for drinking water supply, active smoking, alcohol drinking, eating raw vegetables, eating spicy food, presence of asthmatic/atopic symptoms |

| Khan et al[34] | 2003 | KSA | 15-50 yr | 396 | 51.0% | ELISA IgG-Ab | Higher age |

| Al-Moagel et al[35] | 1989 | KSA | 5-90 yr | 364 | 66.0% | ELISA IgG-Ab | Higher age |

| Al-knawy et al[36] | 1999 | KSA | 2-97 yr | 355 | 67% Mother | Saliva IgG-Ab | The infection was higher in infants when both parents were positive |

| 64% Father | |||||||

| 23% Children | |||||||

| Al-Balushi et al[37] | 2013 | Oman | 15-50 yr | 133 | 69.5% | ELISA IgG-Ab | Increasing age |

| Being male |

ELISA: Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; Ab: Antibody; NA: Not available; UAE: United Arab Emirates; KSA: Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; UBT: Urea breath test.

DISCUSSION

As H. pylori is known to be the responsible pathogen in several gastrointestinal disorders, especially gastric cancer, understanding the epidemiology of H. pylori in different regions is of great importance. More than 60% of gastric cancers occur in developing countries with great variations in different geographical areas[38]. Geographical variations in the prevalence of H. pylori have been established not only in different countries from different regions of the world, but also within regions of a single country. In Ardabil, which has the highest incidence of gastric cancer in Iran, the prevalence of H. pylori among adults aged 40 years and over was estimated to be as high as 90% using the rapid urease test and histopathology[39,40]. This study confirmed a parallel increase in the rate of gastric cancer with increased incidence of H. pylori.

In the current study, the epidemiology of H. pylori infection among the asymptomatic healthy population of Iran and other countries in the EMRO region was reviewed. In Iran, 2 studies reported the prevalence of H. pylori infection among healthy asymptomatic adults (> 18 years). The prevalence of H. pylori infection among asymptomatic healthy adults in Tehran, the capital of Iran, was estimated to be 69% using ELISA[13]. In this study, low education, increasing age, and overcrowding were risk factors for H. pylori infection[13]. In another study conducted in Kerman province (southern Iran), the seroprevalence of H. pylori infection among healthy adults was 67.5% which is comparable to the prevalence in a previous report[15]. Based on the results of the present review, the prevalence of H. pylori in the pediatric age group in Iran seems to be more diverse than in adults. This may be secondary to the different methods of H. pylori detection or different inclusion criteria regarding the age of the study population. However, it should be noted that different sanitary, cultural and educational levels in different Iranian provinces may have an important role in this pattern. This important point should be interpreted cautiously. For instance, Alborzi et al[12] reported a H. pylori prevalence of 82% using stool antigen in Shiraz, a municipal city in southern Iran which is a medical referral center with good sanitary facilities. On the other hand, the prevalence was much lower in other areas with fewer sanitary facilities than Shiraz. The prevalence of H. pylori in the asymptomatic pediatric age group in Rafsanjan, southern Iran, was reported to be 46.6%[14]. In four other studies on healthy pediatric age groups, the prevalence of H. pylori was reported to range from 40% to 65%[18-21].

In other countries of the EMRO, Egypt had the highest prevalence of H. pylori in the healthy asymptomatic population both in adults and the pediatric age group[28,29,31]. Low socioeconomic status, low body weight and height, living in rural areas and lower educational status were risk factors for the acquisition of H. pylori in Egyptian studies[29]. In Saudi Arabia, there has been a decline in the prevalence of H. pylori in the past ten years according to recent reports[33]. Although this decline may be the result of improvements in sanitary conditions, it may be secondary to different methods of H. pylori detection in different studies. Rural residence, crowded housing, low socioeconomic status, the use of tanks for drinking water supply, active smoking, alcohol drinking, eating raw uncooked vegetables, and eating spicy food were risk factors for H. pylori infection in Saudi Arabia[33]. In other countries of the Persian Gulf region, a prevalence of 74%-78% was reported from the United Arab Emirates[26,27] and 70% from Oman[37]. In North African countries, data were available for Libya and Tunisia with an estimated prevalence of 76% and 64%, respectively[24,25].

It should be emphasized that these studies are not concordant regarding the time of study, age of the population and methods of H. pylori detection. Therefore, comparisons of different countries should be made cautiously. However, it is noteworthy that the prevalence is declining with time even in these developing countries. This is compatible with other reports from other parts of the world[41].

Invasive tests for H. pylori detection include histology[42], culture[43], the rapid urease test[44], and molecular studies[45]. These tests have high specificity and sensitivity, but cannot be used for the detection of H. pylori in the healthy asymptomatic population. Non-invasive tests including serology[46], stool antigen[47] and the UBT[48] are also available with different sensitivities and specificities. While serology is the most widely available test for H. pylori detection, the sensitivity of stool antigen and UBT is higher[49]. Therefore, there is no consensus on the gold standard test for H. pylori detection. The studies in this review also used serology or stool antigen testing as non-invasive methods of H. pylori detection.

As reflected in the tables, the overall prevalence was lower in children, and childhood is probably the primary period of acquisition of H. pylori[50,51]. Transmission occurred during childhood via the oral-oral or fecal-oral route[52,53]. Transmission between siblings has also been demonstrated as an important route of transmission[54].

Several treatment regimens have been introduced with different results in different populations[55]. Antibiotic resistance, patient compliance, and environmental factors are among the major factors in eradication failure[56]. Therefore, understanding the epidemiologic burden of H. pylori infection is also critical for programming eradication strategies.

EMRO countries are a group of developing countries located in southwest Asia and North Africa. H. pylori prevalence in EMRO countries is still high in the healthy asymptomatic population. Strategies to improve sanitary facilities, educational status, and socioeconomic status should be implemented to minimize H. pylori infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank Dr. Shokrpour for improving use of the English language in this manuscript.

COMMENTS

Background

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a gram negative, non-spore forming spiral bacterium which colonizes the human stomach and is prevalent worldwide. It has been associated with peptic ulcer disease, gastric adenocarcinoma, and type B low-grade mucosal-associated lymphoma. Furthermore, the organism is also suspected to be involved in other human illnesses such as hematologic and autoimmune disorders, insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome.

Research frontiers

Nearly 50% of the population is infected with H. pylori worldwide, and the prevalence, incidence, age distribution and sequels of infection are significantly different in developed and developing countries. The prevalence of H. pylori infection is decreasing in both developed and developing countries; however, the prevalence is still high in developing countries. In Argentina, the prevalence of a positive urea breath test declined from 41.2% during 2002-2004 to 26% during 2007-2009 among children. Furthermore, the age of infection acquisition is lower in developing countries compared with industrialized nations. It has been estimated that more than 50% of the population aged 5 years is infected and this rate may exceed 90% during adulthood. In a cohort of Brazilian children, the prevalence of H. pylori was 53.4% at baseline and 64.7% 8 years later.

Innovations and breakthroughs

There are no systematic reviews on the prevalence and epidemiology of H. pylori in this geographically important region of the world. This study is a comprehensive review of the epidemiology of H. pylori infection in this area.

Applications

Understanding the epidemiological aspects of H. pylori infection is important and helpful in clarifying the consequences and complications of this infection, and is also fundamental for eradication, treatment, and the pattern of antibiotic resistance.

Peer review

This review on prevalence and risk factors of H. pylori infection is well written and covered up-to-date information regarding epidemiology among healthy population in Iran and countries of Eastern Mediterranean Region.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Engin AB, Federico A, Khedmat H, Tarnawski AS S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Webster JR E- Editor: Ma S

References

- 1.Smolka AJ, Backert S. How Helicobacter pylori infection controls gastric acid secretion. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:609–618. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0592-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asaka M, Dragosics BA. Helicobacter pylori and gastric malignancies. Helicobacter. 2004;9 Suppl 1:35–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-4389.2004.00252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hasni SA. Role of Helicobacter pylori infection in autoimmune diseases. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012;24:429–434. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283542d0b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eshraghian A, Hashemi SA, Hamidian Jahromi A, Eshraghian H, Masoompour SM, Davarpanah MA, Eshraghian K, Taghavi SA. Helicobacter pylori infection as a risk factor for insulin resistance. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1966–1970. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0557-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gunji T, Matsuhashi N, Sato H, Fujibayashi K, Okumura M, Sasabe N, Urabe A. Helicobacter pylori infection is significantly associated with metabolic syndrome in the Japanese population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:3005–3010. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torres J, Pérez-Pérez G, Goodman KJ, Atherton JC, Gold BD, Harris PR, la Garza AM, Guarner J, Muñoz O. A comprehensive review of the natural history of Helicobacter pylori infection in children. Arch Med Res. 2000;31:431–469. doi: 10.1016/s0188-4409(00)00099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janjetic MA, Goldman CG, Barrado DA, Cueto Rua E, Balcarce N, Mantero P, Zubillaga MB, López LB, Boccio JR. Decreasing trend of Helicobacter pylori infection in children with gastrointestinal symptoms from Buenos Aires, Argentina. Helicobacter. 2011;16:316–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bardhan PK. Epidemiological features of Helicobacter pylori infection in developing countries. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:973–978. doi: 10.1086/516067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Queiroz DM, Carneiro JG, Braga-Neto MB, Fialho AB, Fialho AM, Goncalves MH, Rocha GA, Rocha AM, Braga LL. Natural history of Helicobacter pylori infection in childhood: eight-year follow-up cohort study in an urban community in northeast of Brazil. Helicobacter. 2012;17:23–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Afzal M. Health research in the World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. East Mediterr Health J. 2008;14 Suppl:S67–S73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alborzi A, Soltani J, Pourabbas B, Oboodi B, Haghighat M, Hayati M, Rashidi M. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in children (south of Iran) Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;54:259–261. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nouraie M, Latifi-Navid S, Rezvan H, Radmard AR, Maghsudlu M, Zaer-Rezaii H, Amini S, Siavoshi F, Malekzadeh R. Childhood hygienic practice and family education status determine the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in Iran. Helicobacter. 2009;14:40–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jafarzadeh A, Ahmedi-Kahanali J, Bahrami M, Taghipour Z. Seroprevalence of anti-Helicobacter pylori and anti-CagA antibodies among healthy children according to age, sex, ABO blood groups and Rh status in south-east of Iran. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2007;18:165–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jafarzadeh A, Rezayati MT, Nemati M. Specific serum immunoglobulin G to H pylori and CagA in healthy children and adults (south-east of Iran) World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3117–3121. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i22.3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alizadeh AH, Ansari S, Ranjbar M, Shalmani HM, Habibi I, Firouzi M, Zali MR. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori in Nahavand: a population-based study. East Mediterr Health J. 2009;15:129–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghasemi Kebria F, Bagheri H, Semnani S, Ghaemi E. Seroprevalence of anti-Hp and anti-cagA antibodies among healthy persons in Golestan province, northeast of Iran (2010) Caspian J Intern Med. 2011;2:256–260. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jafar S, Jalil A, Soheila N, Sirous S. Prevalence of helicobacter pylori infection in children, a population-based cross-sectional study in west iran. Iran J Pediatr. 2013;23:13–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mikaeli J, Malekzadeh R, Ziad Alizadeh B, Nasseri Moghaddam S, Valizadeh M, Khoncheh R, Massarrat S. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in two Iranian provinces with high and low incidence of gastric carcinoma. Arch Iran Med. 2000;3:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mansour-Ghanaei F, Yousefi Mashhour M, Joukar F, Sedigh M, Bagher-Zadeh AH, Jafarshad R. Prevalence of Helicobacter Pylori Infection among Children in Rasht, Northern Iran. Middle East J Dig Dis. 2009;1:84–88. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahram M, Ahmadi F. Seroprevalence of helicobacterpylori infection among 7-9 year-old children in Zanjan-2004. J Res Med Sci. 2006;11:297–301. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bani-Hani KE, Shatnawi NJ, El Qaderi S, Khader YS, Bani-Hani BK. Prevalence and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection in healthy schoolchildren. Chin J Dig Dis. 2006;7:55–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-9573.2006.00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naous A, Al-Tannir M, Naja Z, Ziade F, El-Rajab M. Fecoprevalence and determinants of Helicobacter pylori infection among asymptomatic children in Lebanon. J Med Liban. 2007;55:138–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bakka AS, Salih BA. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in asymptomatic subjects in Libya. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2002;43:265–268. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(02)00411-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mansour KB, Keita A, Zribi M, Masmoudi A, Zarrouk S, Labbene M, Kallel L, Karoui S, Fekih M, Matri S, et al. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori among Tunisian blood donors (outpatients), symptomatic patients and control subjects. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2010;34:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.gcb.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bener A, Uduman SA, Ameen A, Alwash R, Pasha MA, Usmani MA, AI-Naili SR, Amiri KM. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among low socio-economic workers. J Commun Dis. 2002;34:179–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bener A, Adeyemi EO, Almehdi AM, Ameen A, Beshwari M, Benedict S, Derballa MF. Helicobacter pylori profile in asymptomatic farmers and non-farmers. Int J Environ Health Res. 2006;16:449–454. doi: 10.1080/09603120601093428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salem OE, Youssri AH, Mohammad ON. The prevalence of H. pylori antibodies in asymptomatic young egyptian persons. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 1993;68:333–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohammad MA, Hussein L, Coward A, Jackson SJ. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among Egyptian children: impact of social background and effect on growth. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11:230–236. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007000481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naficy AB, Frenck RW, Abu-Elyazeed R, Kim Y, Rao MR, Savarino SJ, Wierzba TF, Hall E, Clemens JD. Seroepidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection in a population of Egyptian children. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:928–932. doi: 10.1093/ije/29.5.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bassily S, Frenck RW, Mohareb EW, Wierzba T, Savarino S, Hall E, Kotkat A, Naficy A, Hyams KC, Clemens J. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori among Egyptian newborns and their mothers: a preliminary report. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:37–40. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al Faleh FZ, Ali S, Aljebreen AM, Alhammad E, Abdo AA. Seroprevalence rates of Helicobacter pylori and viral hepatitis A among adolescents in three regions of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: is there any correlation? Helicobacter. 2010;15:532–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2010.00800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanafi MI, Mohamed AM. Helicobacter pylori infection: seroprevalence and predictors among healthy individuals in Al Madinah, Saudi Arabia. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2013;88:40–45. doi: 10.1097/01.EPX.0000427043.99834.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khan MA, Ghazi HO. Helicobacter pylori infection in asymptomatic subjects in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. J Pak Med Assoc. 2007;57:114–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Al-Moagel MA, Evans DG, Abdulghani ME, Adam E, Evans DJ, Malaty HM, Graham DY. Prevalence of Helicobacter (formerly Campylobacter) pylori infection in Saudia Arabia, and comparison of those with and without upper gastrointestinal symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:944–948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Al-Knawy BA, Ahmed ME, Mirdad S, ElMekki A, Al-Ammari O. Intrafamilial clustering of Helicobacter pylori infection in Saudi Arabia. Can J Gastroenterol. 2000;14:772–774. doi: 10.1155/2000/952965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al-Balushi MS, Al-Busaidi JZ, Al-Daihani MS, Shafeeq MO, Hasson SS. Sero-prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among asymptomatic healthy Omani blood donors. Asia Pac J Trop Dis. 2013;3:146–149. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Graham DY, Lu H, Yamaoka Y. African, Asian or Indian enigma, the East Asian Helicobacter pylori: facts or medical myths. J Dig Dis. 2009;10:77–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2009.00368.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malekzadeh R, Sotoudeh M, Derakhshan MH, Mikaeli J, Yazdanbod A, Merat S, Yoonessi A, Tavangar M, Abedi BA, Sotoudehmanesh R, et al. Prevalence of gastric precancerous lesions in Ardabil, a high incidence province for gastric adenocarcinoma in the northwest of Iran. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:37–42. doi: 10.1136/jcp.57.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sotoudeh M, Derakhshan MH, Abedi-Ardakani B, Nouraie M, Yazdanbod A, Tavangar SM, Mikaeli J, Merat S, Malekzadeh R. Critical role of Helicobacter pylori in the pattern of gastritis and carditis in residents of an area with high prevalence of gastric cardia cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:27–33. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9817-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.World Gastroenterology Organisation. World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guideline: Helicobacter pylori in developing countries. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:383–388. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31820fb8f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Braden B. Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. BMJ. 2012;344:e828. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi YJ, Kim N, Lim J, Jo SY, Shin CM, Lee HS, Lee SH, Park YS, Hwang JH, Kim JW, et al. Accuracy of diagnostic tests for Helicobacter pylori in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding. Helicobacter. 2012;17:77–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koumi A, Filippidis T, Leontara V, Makri L, Panos MZ. Detection of Helicobacter pylori: A faster urease test can save resources. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:349–353. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i3.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Woo HY, Park DI, Park H, Kim MK, Kim DH, Kim IS, Kim YJ. Dual-priming oligonucleotide-based multiplex PCR for the detection of Helicobacter pylori and determination of clarithromycin resistance with gastric biopsy specimens. Helicobacter. 2009;14:22–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, Atherton J, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gensini GF, Gisbert JP, Graham DY, Rokkas T, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection--the Maastricht IV/ Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646–664. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shimoyama T, Sawaya M, Ishiguro A, Hanabata N, Yoshimura T, Fukuda S. Applicability of a rapid stool antigen test, using monoclonal antibody to catalase, for the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:487–491. doi: 10.1007/s00535-011-0371-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leal YA, Flores LL, Fuentes-Pananá EM, Cedillo-Rivera R, Torres J. 13C-urea breath test for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 2011;16:327–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garza-González E, Perez-Perez GI, Maldonado-Garza HJ, Bosques-Padilla FJ. A review of Helicobacter pylori diagnosis, treatment, and methods to detect eradication. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:1438–1449. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i6.1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Malaty HM, Graham DY. Importance of childhood socioeconomic status on the current prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut. 1994;35:742–745. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.6.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Opekun AR, Gilger MA, Denyes SM, Nirken MH, Philip SP, Osato MS, Malaty HM, Hicks J, Graham DY. Helicobacter pylori infection in children of Texas. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;31:405–410. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200010000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jones N, Chiba N, Fallone C, Thompson A, Hunt R, Jacobson K, Goodman K; Canadian Helicobacter Study Group Participants. Helicobacter pylori in First Nations and recent immigrant populations in Canada. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26:97–103. doi: 10.1155/2012/174529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vale FF, Vítor JM. Transmission pathway of Helicobacter pylori: does food play a role in rural and urban areas? Int J Food Microbiol. 2010;138:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cervantes DT, Fischbach LA, Goodman KJ, Phillips CV, Chen S, Broussard CS. Exposure to Helicobacter pylori-positive siblings and persistence of Helicobacter pylori infection in early childhood. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50:481–485. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181bab2ee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Taghavi SA, Jafari A, Eshraghian A. Efficacy of a new therapeutic regimen versus two routinely prescribed treatments for eradication of Helicobacter pylori: a randomized, double-blind study of doxycycline, co-amoxiclav, and omeprazole in Iranian patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:599–603. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0374-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Camargo MC, García A, Riquelme A, Otero W, Camargo CA, Hernandez-García T, Candia R, Bruce MG, Rabkin CS. The problem of Helicobacter pylori resistance to antibiotics: a systematic review in Latin America. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:485–495. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]