Abstract

Local neurons in the vertebrate retina are instrumental in transforming visual inputs to extract contrast, motion, and color information and in shaping bipolar-to-ganglion cell transmission to the brain. In Drosophila, UV vision is represented by R7 inner photoreceptor neurons that project to the medulla M6 stratum, with relatively little known of this downstream substrate. Here, using R7 terminals as references, we generated a 3D volume model of the M6 stratum, which revealed a retinotopic map for UV representations. Using this volume model as a common 3D framework, we compiled and analyzed the spatial distributions of more than 200 single M6-specific local neurons (M6-LNs). Based on the segregation of putative dendrites and axons, these local neurons were classified into two families, directional and nondirectional. Neurotransmitter immunostaining suggested a signal routing model in which some visual information is relayed by directional M6-LNs from the anterior to the posterior M6 and all visual information is inhibited by a diverse population of nondirectional M6-LNs covering the entire M6 stratum. Our findings suggest that the Drosophila medulla M6 stratum contains diverse LNs that form repeating functional modules similar to those found in the vertebrate inner plexiform layer. J. Comp. Neurol. 522:3795–3816, 2014. © 2014 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Keywords: UV circuit, vision, retinotopic map

The neural circuits underlying vision in flies exhibit striking similarities to those of vertebrates (Sanes and Zipursky, 2010). In the vertebrate retina, rods and cones serve as photoreceptor neurons that deliver light-evoked signals to dendrites of bipolar cells in the outer plexiform layer (Wassle, 2004; Li and DeVries, 2006). Each of ∼10 types of bipolar cells carries a different parameter of visual information and synapses with the dendrites of specific types of ganglion cell at a unique depth of the inner plexiform layer, forming a stratic structure (Famiglietti and Kolb, 1976; Wu et al., 2000). Modulated by amacrine cells ramifying horizontally within specific strata or vertically over several strata (MacNeil and Masland, 1998; MacNeil et al., 1999), complex visual signals become progressively more selectively tuned as they proceed through a series of synaptic sublamina (Sanes and Zipursky, 2010). The diverse morphological and biochemical features of amacrine cells indicate their multifaceted functions (MacNeil and Masland, 1998; MacNeil et al., 1999; Roska and Werblin, 2001; Roska et al., 2006). Consequently, it has been suggested that, in the inner plexiform layer, each stratum innervated by its own input, output, and local neurons (LNs) is responsible for a unique visual representation (Sanes and Zipursky, 2010; Werblin, 2011). It remains to be confirmed whether such morphological and functional variation in the inner plexiform layer is evolutionarily conserved and is found in the Drosophila visual system.

The Drosophila compound eye has approximately 800 ommatidia, and each ommatidium contains eight photoreceptor neurons. Six outer photoreceptor neurons (i.e., R1–R6, which express the blue/green-sensitive rhodopsin Rh1) surround two inner photoreceptor neurons (R7 on top of R8). The ommatidia are of three kinds, differing in the rhodopsin types expressed in R7 and R8 (Wernet et al., 2003). The pale ommatidia express the UV-sensitive Rh3 in R7 and the blue-sensitive Rh5 in R8, whereas the yellow ommatidia express UV-sensitive Rh4 in R7 and green-sensitive Rh6 in R8. These two types of ommatidium are stochastically distributed throughout the main part of the retina. A third type forms one or two rows of ommatidia at the dorsal margin of the Drosophila eye, a specialized region known as the dorsal rim area (DRA) where Rh3 is expressed in both R7 and R8 neurons (Fortini and Rubin, 1990,1991).

The Drosophila optic lobe contains four neuropils, each representing a different stage of visual processing: the lamina, medulla, lobula, and lobula plate (Morante and Desplan, 2004). Starting with the compound eye, visual signals are transmitted through a two-dimensional array of modular longitudinal structures called cartridges in the lamina and columns in the other three neuropils, which retains the spatial organization of the visual field captured by the ommatidia. In the medulla, each column is subdivided into 10 strata (M1–M10) with R7, R8, and the monopolar L1–L5 neurons of the lamina specifically terminating in one or a few of the distal (relative to brain) M1–M6 strata (Fischbach and Dittrich, 1989; Meinertzhagen and Sorra, 2001; Morante and Desplan, 2004; Takemura et al., 2008). R7 and R8 neurons terminate in M6 and M3, respectively, making the medulla the first stage of color-vision processing and simultaneously the second stage of motion-detection processing through L1–L5 neurons. Converging evidence from studies conducted in several insect species, including Drosophila, indicates that DRA ommatidia are sensitive to the oscillation plane (E-vector orientation) of linearly polarized light (Hardie, 1984; Labhart and Meyer, 1999; Wernet et al., 2012).

Drosophila has been a great model organism for studying the role of LNs across several sensory modalities. The diversity and variability of LNs in the Drosophila antennal lobe are essential for olfactory information processing (Wilson and Laurent, 2005; Olsen et al., 2007; Olsen and Wilson, 2008; Chou et al., 2010; Seki et al., 2010). Such LNs also exist in the antennal mechanosensory and motor centers for acoustic information processing (Lai et al., 2012; Lehnert et al., 2013).

As the largest neuropil in the Drosophila brain, the medulla contains more than 30 morphologically distinct types of neuron, having branches that are extensive yet limited to the region (Fischbach and Dittrich, 1989; Morante and Desplan, 2008; Raghu and Borst, 2011; Raghu et al., ,). Few of their arborizations display layer specificity (e.g., Dm1 and Dm6 in M1; Pm1 and Pm2 in M9), leaving open the question of whether each of the 10 medulla strata functions as a distinct unit, with its own layer-specific LNs for visual information processing, in a manner similar to mammalian amacrine cells in the inner plexiform strata.

Here, by morphologically aligning and warping 233 single LNs into a common M6 volume model defined by R7 terminals, we demonstrate that the M6 stratum contains at least two morphologically distinct families of M6-specific LNs (M6-LNs), the directional and nondirectional LNs. Each family contains a diverse population of neurons, which differ in their size, shape, location, and coverage of the retinotopic field.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid constructs

pP[UAST-Brainbow2.1R-2] and pCaspeR-hs-CRE-HA constructs were created by standard cloning techniques. CMV-Brainbow-2.1 R (Livet et al., 2007) was purchased from Addgene (Cambridge, MA; plasmid 18723) and contains four cassettes of fluorescent protein (hrGFPII-NLS, eYFP, tdimer2, and M-mCerulean), each containing a loxp site linked to a fluorescent protein-coding region and a terminator. The CMV-Brainbow-2.1 R clone contains NheI and XhoI cutting sites for the release of the full four cassettes; hence, this region was cloned into the XhoI and XbaI sites of the pP[UAST-AI] vector (Kuo et al., 2012) to create the pP[UAST-Brainbow2.1R-2] transgene. pAD-CRE-HA was also purchased from Addgene (plasmid 16583) and contains XhaI and NheI cutting sites for the release of CRE-HA; hence, the CRE-HA gene was cloned into the XbaI site of the pCaspeR-hs vector (DGRC 1215) to create the pCaspeR-hs-CRE-HA transgene.

Fly stocks

Fly stocks were grown on standard corn medium at 25°C and 60% relative humidity, under a 14:10-hour light:dark cycle. The following fly stocks were used: PanR7-GAL4, PanR8-GAL4, Rh3-LexA, UAS-hth, UAS-hthHM (provided by Claude Desplan), C202a-GAL4, 21D-GAL4 (Rister et al., 2007), Cha3.3kb-GAL80 (Kitamoto, 2002), UAS-Dscam::GFP (Wang et al., 2004), UAS-Syt::HA (Jefferis et al., 2007), UAS-FB1.0260b;hs-mFlp5 (Hadjieconomou et al., 2011), GMR-GAL4, Rh5-GAL4, Rh6-GAL4, 30A-GAL4 (Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, stock number BL-37534), and VT12760. For mosaic analysis with a repressible marker (MARCM) to label single neurons, FRT19A,UAS-mCD8::GFP;30A-GAL4 was crossed with hs-FLP,FRT19A,tubGAL80;+;TM3/UAS-syt::HA, and FRTg13, UAS-mCD8::GFP;VT12760 was crossed with hs-FLP;FRTg13,tubGAL80 (Lee and Luo, 1999). Flippase was activated by keeping third-instar larvae at 37°C for 45 minutes. For polarity analysis, 30A-GAL4;Cha3.3kb-GAL80,UAS-GAL4, 30A-GAL4, or VT12760 was crossed with UAS-Dscam::GFP;UAS-mko;UAS-Syt::HA/TM3. The UAS-Syt::HA (III) line was generated by remobilizing the P-element insertion from a starter line (Jefferis et al., 2007). For Flybow analysis, 30A-GAL4;Cha3.3kb-GAL80,UAS-GAL4 or 30A-GAL4 was crossed with UAS-FB1.0260b;hs-mFlp5. Flippase was activated by keeping pupae at 37°C for 45 minutes. For Brainbow analysis, w,UAS-Brainbow2.1R-2;30A-GAL4 or w,UAS-Brainbow2.1R-2;VT12760 was crossed with hs-CRE-HA. Flippase was activated by keeping pupae at 37°C for 15 minutes.

Antibody characterization

Table1 lists the primary antibodies used in this study, with their sources and specificity tests on Drosophila tissue. Anti-Dscs large (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank; catalog No. 4F3 anti-discs large, RRID:AB_528203) antibody was raised against a fragment that includes the second PDZ domain of DLG fused to GST. It strongly labels the lamina and central brain neuropils in Drosophila (Hamanaka and Meinertzhagen, 2010). This monoclonal anti-DLG antibody labels larval neuromuscular junctions in a pattern similar to that of a widely used polyclonal anti-DLG antibody (Lahey et al., 1994; Parnas et al., 2001).

Table 1.

Primary Antibodies Used for Immunohistochemistry

| Antibody | Immunogen | Source | Dilution | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse anti-DLG | DLG PDZ2 domain fused to GST | DSHB, Iowa City, IA | 1:50 | Drosophila lamina and central brain (Hamanaka and Meinertzhagen, 2010) |

| Drosophila larva NMJ (Lahey et al., 1994; Parnas et al., 2001) | ||||

| Rabbit anti-HA | YPYDVPDYA (influenza hemagglutinin-HA-epitope) conjugated to KLH | Abcam, ab9110 | 1:500 | Transgenically expressed in Drosophila PN axons (Jefferis et al., 2007) |

| Rabbit anti-5HT | Serotonin creatinine sulfate complex conjugated to BSA | Sigma, S5545 | 1:500 | Colocalized immunoreactivity with tryptophan hydroxylase (Park et al., 2006; Huser et al., 2012) |

| Rabbit anti-GABA | γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) conjugated to BSA | Sigma, A2052 | 1:500 | Drosophila lamina C2 neurons (Enell et al., 2007; Kolodziejczyk et al., 2008) |

| Rabbit anti-DVGLUT | The peptide CQMPSYDPQGYQQQ encoding amino acids 620–632 of DVGLUT | A. DiAntonio (Washington University School of Medicine) | 1:5,000 | Transgenically expressed in Drosophila embryo (Daniels et al., 2004) |

| Western blotting characterization (Daniels et al., 2006) |

Anti-5HT (5-hydroxytryptamine) antibody was produced in rabbit by using serotonin–creatinine sulfate complex conjugated to bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the immunogen and was then affinity immunopurified. The immunopositive signal can be inhibited by preincubation of diluted antiserum with serotonin or serotonin–BSA (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO; catalog No. S5545, RRID:AB_477522). Staining specificity in the Drosophila brain has been demonstrated by immunoreactivity of anti-5HT antibody in the tryptophan hydroxylase promoter-driven neurons (Huser et al., 2012) that are antitryptophan hydroxylase immunopositive (Park et al., 2006). Tryptophan hydroxylase is the key enzyme for 5HT biosynthesis.

Anti-γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA; Sigma) antibody against GABA–BSA conjugate was produced in rabbit, affinity immunopurified, and characterized by dot blot immunoassay (Sigma-Aldrich; catalog No. A2052, RRID:AB_477652). Staining specificity in the Drosophila brain has been demonstrated in the lamina C2 neurons by colocalization of immunopositive signals from the anti-GABA antibody with those from antibodies against glutamic acid decarboxylase, the key enzyme for GABA biosynthesis (Kolodziejczyk et al., 2008) and Drosophila vesicular GABA transporter (Enell et al., 2007).

Anti-Drosophila vesicular glutamate transporter (DVGLUT; a gift from Dr. A. DiAntonio, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO; Dr. A. Diantonio; catalog No. NA, RRID:AB_2307294) was raised against the C-terminal peptide (see Table1 for sequence) of DVGLUT. This antiserum was affinity purified and found to recognize a single band of DVGLUT of the expected molecular weight (2.3 kD) in Western blots (Daniels et al., 2004). Its specificity was further confirmed by the finding of a reduced immunopositive signal in a hypomorphic dvglut allele expressing low levels of DVGLUT protein (Daniels et al., 2006).

Sample preparation

Brain samples were dissected in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 30 minutes. Samples were then blocked and permeabilized in PBS containing 1% Triton X-100 and 10% normal goat serum (PBS-T) and degassed in a vacuum chamber to expel tracheal air, with six cycles of depressurization to 70 cmHg, holding pressure at this value for 10 minutes in each cycle. Next, the brain samples were incubated in PBS-T, which contained one of the following (see Table1): 1:50 mouse 4F3 anti-Discs large (DLG) monoclonal antibody for neuropil counterstaining, 1:500 rabbit anti-HA (Abcam, Cambridge, MA; catalog No. ab9110, RRID:AB_307019) for MARCM single neuron polarity labeling, 1:500 rabbit anti-5HT for labeling putative serotonergic neurons, 1:500 rabbit anti-GABA for labeling putative GABAergic neurons, or 1:5,000 rabbit anti-DVGLUT (Daniels et al., 2004) for labeling putative glutamatergic neurons, all overnight at room temperature. After being washed three times in PBS-T, the samples were incubated in PBS-T containing 1:250 biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG, biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG, or Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) overnight at room temperature. Next, the brain samples were washed and incubated with 1:500 Alexa Fluor 635 streptavidin (Molecular Probes), again overnight at room temperature. Finally, after extensive washing, the immunolabeled brain samples were directly cleared in FocusClear (CelExplorer, Taiwan). Samples were imaged under a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope with either a ×40 C-Apochromat water-immersion objective lens (N.A. 1.2, working distance 220 μm) or a ×63 Plan-Apochromat oil-immersion objective lens (N.A. 1.4). The following settings were used: scanning speed 6, resolution 1,024 × 1,024, line averaged 4×, zoom 0.7, and optical slice 1 μm for the ×40 lens and 0.75 μm for the ×63 lens. The corrected voxel size was x:y:z = 0.32 × 0.32 × 1 μm for the ×40 lens and x:y:z = 0.18 × 0.18 × 0.75 μm for the ×63 lens.

3D model generation

The optic lobe from an intact dissected brain was recorded with the ×63 lens for the whole medulla and M6 stratum, with manual segmentation performed in Amira 4.1.2 (now Avizo, Visualization Science Group, Merignac, France; RRID:nif-0000–00262). The segmented medulla model was automatically warped into the medulla model from the standard brain of FlyCircuit (Chiang et al., 2011), and the M6 stratum in our sample was then carried over into this model. The GMR-GAL4 expressing pattern was manually segmented in Amira 4.1.2 and compiled into the common 3D framework of our representative M6 volume model, as described above. Global and local registrations were performed as described previously (Chiang et al., 2011), by applying the automated global affine registration and the optic-lobe-specific local registration. The registration precision was estimated to be 3.9 ± 0.4 μm after global registration and 1.1 ± 0.2 μm after local registration (Chiang et al., 2011). Single M6-LNs were identified by manually examining the original confocal stacks, in which M1–M6 layers were labeled by anti-DLG immunostaining. Individual neurons were segmented and registered in the same way as described above. The hypothetical innervating columns in the retinotopic model were visually identified and manually colored.

RESULTS

Analytical strategy

Here we describe our procedure for the analysis of spatial relationships between R7/R8 terminals and M6-LNs in the medulla. First, we generated a volume model of the M6 stratum, defined by the array of terminals of specific kinds of columnar neurons. We then generated an internal retinotopic map, by intersecting (displaying the overlaps of) the M6 volume model and the terminals of photoreceptor neurons. Second, we visually identified 200 single LNs with arborizations exclusively in the M6 stratum, based on the location of GFP expression relative to the DLG immunostaining background in the raw image of each sample brain. Third, using the M6 volume model as a common 3D framework, we compiled all of the single M6-LNs, and predicted the pattern of innervation of the retinotopic field by each individual M6-LN. Finally, we classified these M6-LNs into two families based on the retinotopic coverage and further verified this categorization with polarity labeling, neurotransmitter immunostaining, and Cha-Gal80 (a neuronal transcription repressor) subtraction.

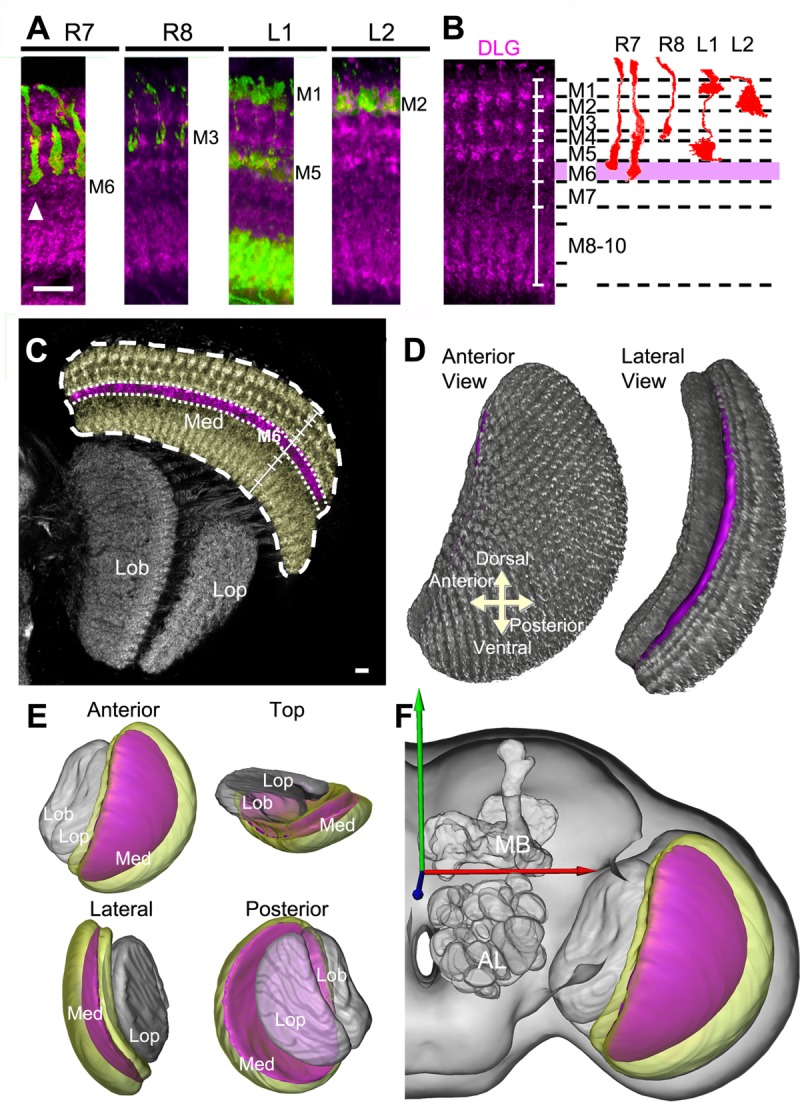

Generation of the M6 volume model

The medulla has previously been subdivided into 10 neuropilar strata, based on neurite arborizations of selected input neurons at a specific stratum (Fischbach and Dittrich, 1989). To identify the boundary of each specific medulla stratum, we used the following drivers as references: Rh3-LexA, which labels both short- and long-form R7 neurons terminating at the middle and at the lower boundary of M6, respectively (Fischbach and Dittrich, 1989); Rh5-GAL4, which labels R8 neurons terminating at M3; c202a-GAL4, which labels L1 neurons terminating at M1 and M5; and 21D-GAL4, which labels L2 neurons terminating at M2 (Fig. 1A). These landmark references allowed us to identify reliably specific distal medulla strata directly from brains immunostained with the postsynaptic density marker anti-DLG. M7, also referred to as the serpentine layer, is the stratum with the weakest intensity of anti-DLG immunostaining, separating the distal medulla (M1–M6) from the proximal medulla (M8–M10). In the distal medulla, the strata show alternating levels of DLG-immunostaining intensity, with M2, the proximal half of M3, and M5 staining more intensely than other strata (Fig. 1B). Next, we manually demarcated the boundaries of the M6 stratum and of the entire medulla (Fig. 1C) and generated a 3D volume model (Fig. 1D,E). The reconstructed M6 model took the form of a 5-μm-thick concave dish. To analyze UV representation in the M6 stratum, the reconstructed volume model and images of all single neurons presented below were aligned and warped into the standard model brain in the FlyCircuit database, using DLG-immunostaining channels as their common references (Fig. 1F; http://www.flycircuit.tw/; Chiang et al., 2011).

Figure 1.

Generation of medulla volume models. A: Arborizations of retinotopic afferents (green) within medulla columns in relation to DLG-immunostained medulla strata (magenta). A long-form R7 (arrowhead) defines the proximal boundary of M6. B: Identification of specific strata in the distal medulla (M1–M6) based on differences in DLG-immunostaining intensity (left), using specific columnar neurons as references (right). C: Segmentation of the M6 stratum (magenta) and medulla (yellow) from the DLG-immunostained optic lobe (gray). D: Volume rendering of the M6 stratum (magenta) within the medulla (gray). E: Spatial relationship of M6 (magenta), medulla (yellow), lobula, and lobula plate (gray) volume models. F: The M6 volume model provided by the standard model fly brain. Med, medulla; Lob, lobula; Lop, lobula plate; MB, mushroom body; AL, antennal lobe. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Generation of the M6 retinotopic map

The glass multiple reporter (GMR) promoter element drives GAL4 expression in all photoreceptor neurons in the Drosophila optic lobe (Freeman, 1996; see also Fig. 2A,B), and M6 is the deepest stratum in the medulla innervated by GMR-GAL4 neurons. Note that GMR-GAL4 was also expressed in the eyelet neurons that form an axonal bundle bypassing the medulla to terminate at the accessory medulla (Fig. 2A,B), a small triangular neuropil at the anterior-medial edge of the medulla (Yasuyama and Meinertzhagen, 1999). Using an intersection between the GMR-GAL4 neurons and the M6 volume model, we generated an internal representation of the retinotopic inputs in the M6 stratum (Fig. 2C–F, Supp. Info. Movie 1). The spatial distribution of the intersected retinotopic inputs showed a hexagonal pattern, with a maximum of ∼30 columns from the anterior boundary to the posterior edge.

Figure 2.

Retinotopic map in the M6 stratum. A: Frontal view of the GMR-GAL4 expression pattern in the optic lobe. B: Rear view of terminals of GMR-GAL4-labeled neurons in the medulla. Locations of closeup images in G and H are indicated. Arrow indicates the axonal terminal in the accessory medulla. C: The sample M6 surface model is warped into the medulla of the standard M6 model. D: GMR-GAL4-labeled neurons are warped into the standard M6 volume model, using the transformation matrix generated in C. E: Schematic illustration of an R7 neuron terminating at the M6 stratum. F: The M6 retinotopic map generated by the intersection (overlap) between terminals of GMR-GAL4 neurons and the M6 volume model. G: Transverse section of the ventral medulla, showing an array of the typical R7 terminals that occur in most parts of M6 stratum. H: Transverse section of the dorsal medulla, showing dual terminals (arrows) in the dorsal-posterior part of the M6 stratum. Other R8s in inner columns terminate at M3 (arrowhead). I: Preferential expression of PanR7-GAL4, showing that the dual terminals at the dorsal-posterior M6 stratum (arrows) are derived from DRA R7 and R8 neurons. PanR8-GAL4 (J) and Rh6-GAL4 (K), both expressing in R8, innervating M6 (arrow) in the dorsal-posterior region and M3 (arrowhead) in all other regions. L: Dual expression of Rh3-LexA (yellow) and Rh6-GAL4 (cyan) labels the dual terminals (arrows) at dorsal-posterior M6 with different colors. Rh6-GAL4 also labels R8s terminating at M3 (arrowhead) in other medulla regions. M: Ectopic expression of hth in all photoreceptor neurons driven by GMR-GAL4 induces dual terminals (arrows) at medial M6 stratum. N: Overexpression of hthHM in all photoreceptor neurons driven by GMR-GAL4 induces single terminals (arrow) at dorsal-posterior M6. Scale bars = 10 μm.

High-resolution imaging indicated that each M6 column contained one swollen terminal derived from an R7 neuron (Fig. 2G), except at the dorsal-posterior M6, where terminals were significantly larger (Fig. 2F). A closer examination revealed that dual terminals from ∼30 paired photoreceptor neurons contributed to the larger terminals in the dorsal-posterior M6 (Fig. 2H). The dual terminals along the M6 dorsal-posterior edge were also observed in PanR7-GAL4 (Fig. 2J), which was preferentially expressed in R7 and DRA R8 neurons (Lee et al., 2001; Wernet et al., 2006). Surprisingly, we found that neurons in Pan R8-GAL4 (Mikeladze-Dvali et al., 2005; Fig. 2J), Rh6-GAL4 (Fig. 2K), and Rh3-LexA (Fig. 3F) have a single terminal at the dorsal-posterior M6. Two-color labeling indicated that the proximal long-form terminals were from Rh3-LexA-positive neurons and that the distal short-form terminals were from Rh6-GAL4-positive neurons (Fig. 2L). The dual terminals could be induced by ectopically expressing DRA ommatidia-inducing homothorax (hth; Wernet et al., 2003; Fig. 2M) in all photoreceptors terminating at other M6 regions, which originally had only one terminal (Fig. 2K). Furthermore, terminals at the dorsal-posterior M6 could be altered to single terminals by overexpressing the dominant-negative form of Hth (hthHM; Ryoo et al., 1999; Fig. 2N), which leads to a loss of the DRA ommatidia (Wernet et al., 2003). Together, these results suggest that the dual terminals at dorsal-posterior M6 arise from DRA R7 and R8.

Figure 3.

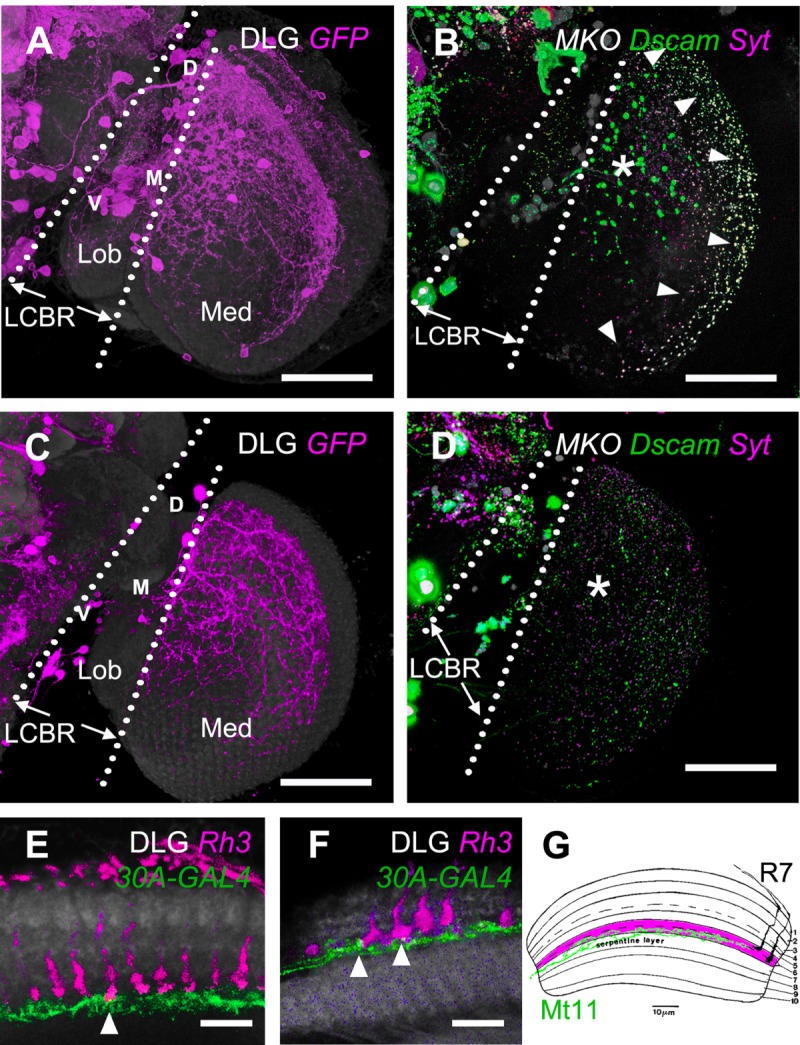

A specific driver of M6-LNs. A: Expression pattern of 30A-GAL4 (magenta). The brain is immunostained with anti-DLG (gray). Locations of M6-LN cell bodies at the ventral (V), medial (M), and dorsal (D) LCBR are marked. B: Presynaptic marker Syt::HA (magenta) and postsynaptic marker Dscam-GFP (green) in the 30A-GAL4 neurons labeled by MKO (gray). C: Expression pattern of 30A-GAL4;Cha-GAL80. The brain is immunostained with anti-DLG (gray). D: Presynaptic marker Syt::HA (magenta) and postsynaptic marker Dscam-GFP (green) in the 30A-GAL4;Cha-GAL80 neurons labeled by MKO (gray). The intense Dscam-GFP signal at the anterior M6 (asterisk), and the overlapping Dscam-GFP/Syt::HA signal at the posterior M6 (arrowhead) in B is absent in D. LCBR, lateral cell body rind; Med, medulla; Lob, lobula. E,F: Dual expression of 30A-GAL4 (green) and Rh3-LexA (magenta) in anti-DLG immunostained medulla (gray). At the medial M6 (E), only long-form R7 (arrowhead) intersects with M6-LNs (green). At the dorsal-posterior M6 (F), all R7s intersect with M6-LNs. G: A merged illustration of Mt11 (green) and two forms of R7 in medulla from Fischbach and Dittrich (1989). The restriction of the terminals of Mt11 to the proximal half of layer M6 is similar to that of the M6-LNs expressed by 30A-GAL4. Scale bars = 50 μm in A–D; 10 μm in E,F.

Identification of M6-LNs

From among the 3,000 single neurons with all processes restricted to the medulla that are found in the FlyCircuit image database (http://www.flycircuit.tw/; Chiang et al., 2011), we visually identified 155 neurons having arborizations restricted to the M6 stratum in every sample brain (Supp. Info. Movie 2). We further characterized these M6-LNs by using 30A-GAL4, a driver with preferential expression in some M6-LNs that consistently project dense fibers to the anterior-dorsal and posterior edges and sparse fibers to the center field (Fig. 3A; n = 10). Using synaptotagmin::HA (Syt::HA) and Dscam::GFP to label putative axons and dendrites, respectively, we found that axonal terminals were distributed throughout the whole M6 retinotopic field and were homogeneous in size and shape (Fig. 3B). In contrast, dendritic terminals were of two different sizes. Large dendritic terminals were distributed exclusively at the anterior M6 (Fig. 3B, asterisk), and small dendritic terminals were distributed throughout the whole M6 and mostly colocalized with axonal terminals along the posterior M6 edge (Fig. 3B, arrowheads). In the presence of Cha-GAL80 inhibition, 30A-GAL4 was expressed in fewer M6-LNs (Fig. 3C). These Cha-GAL80-negative neurons had small dendritic terminals and noncolocalized axonal terminals (Fig. 3D), indicating that M6-LNs with large dendritic terminals are Cha-GAL80 positive (Fig. 3D, asterisk), and their axonal terminals colocalized with the dendritic terminals of Cha-GAL80-negative neurons at the posterior M6 edge (Fig. 3B). Therefore, Cha-GAL80 inhibition revealed two M6-LN families and their divergence in hard wiring.

Three-color imaging of R7 neurons in Rh3-LexA, M6-LNs in 30A-GAL4, and DLG background immunolabeling showed that the M6-LN terminals were distributed exclusively in the proximal half of the M6 stratum, where they interdigitated with long-form R7 terminals (Fig. 3E), especially at the dorsal-posterior region where Rh3-LexA was expressed in many long-form R7s (Fig. 3F). Intriguingly, most R7 terminals were of the short form that were distributed in the distal half of the M6 stratum, suggesting that most R7s do not directly intersect with the M6-LNs. The M6-LNs projected their primary neurites along the M7 stratum (Fig. 3E,F), which is similar to the reported Mt11 neuron that also restricts its synaptic arborizations to the proximal half of the M6 stratum (Fig. 3G; Fischbach and Dittrich, 1989).

Diversity of M6-LNs

Using MARCM labeling, together with Syt::HA as a presynaptic marker, we imaged 45 additional M6-LNs in 30A-GAL4 and analyzed their dendrite–axon distributions. The cell bodies of the 200 identified M6-LNs were all located at the anterior part of the lateral cell body rind (LCBR), between the optic lobe and the central brain. We classified these M6-LNs into two morphologically distinct families, directional and nondirectional neurons (Table2).

Table 2.

Categorization of M6-LNs

| Family | Neuron variety | Cell body location | Column coverage | Expression | Immunopositive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Directional | Medial or dorsal | 157 ± 60/65.3 ± 8.3 (n = 9) | VGlut-GAL4 (n = 129) | Unknown | |

| fru-GAL4 (n = 18) | Unknown | ||||

| 30A-GAL4 (n = 6) | Anti-DVGLUT | ||||

| Nondirectional | M6-LN1 | Ventral | 60.7 ± 5.0 (n = 3) | 30A-GAL4 (n = 24) | Anti-GABA |

| M6-LN2 | Ventral | 80.3 ± 5.0 (n = 3) | Cha-GAL4 (n = 1) | Unknown | |

| 30A-GAL4 (n = 4) | Anti-GABA | ||||

| M6-LN3 | Ventral | 148.0 ± 15.8 (n = 3) | VGlut-GAL4 (n = 2) | Unknown | |

| 30A-GAL4 (n = 5) | Anti-GABA | ||||

| M6-LN4 | Dorsal | 157 (n = 1) | VGlut-GAL4 (n = 1) | Unknown | |

| 30A-GAL4 (n = 6) | Unknown | ||||

| M6-LN5 | Ventral | 114 (n = 1) | Gad1-GAL4 (n = 1) | Unknown | |

| M6-LN6 | Ventral | 102 (n = 1) | Cha-GAL4 (n = 1) | Unknown | |

| M6-LN7 | Dorsal | 387 (n = 1) | Trh-GAL4 (n = 2) | Unknown | |

| M6-LN8 | Dorsal | 148 ± 25.5 (n = 2) | VT12760-GAL4 (n = 4) | Anti-GABA | |

| M6-LN9 | Dorsal | 40 ± 1.4 (n = 2) | VT12760-GAL4 (n = 4) | Anti-GABA | |

| M6-LN10 | Dorsal | 111.5 ± 26.2 (n = 2) | VT12760-GAL4 (n = 4) | Anti-GABA | |

| M6-LN11 | Dorsal | 51 ± 5.0 (n = 3) | VT12760-GAL4 (n = 8) | Anti-GABA | |

| M6-LN12 | Dorsal | 54 ± 5.6 (n = 3) | VT12760-GAL4 (n = 7) | Anti-GABA | |

| M6-LN13 | Dorsal | 74 (n = 1) | VT12760-GAL4 (n = 6) | Anti-GABA | |

| Two families | 13 Clusters | 233 Single neurons | |||

Number of retinotopic columns covered by individual M6-LNs (mean ± SD).

Number of anterior/posterior retinotopic columns.

The directional M6-LNs (n = 153) were characterized by their segregated fibers with putative dendrites at the anterior M6 stratum and Syt::HA-positive axons at the posterior M6 stratum (Fig. 4A). Individual directional M6-LNs varied greatly in their innervation of M6 retinotopic columns (Fig. 4B). Aligning all of the imaged directional M6-LNs into the common M6 retinotopic model revealed the unidirectional relay of visual information from the anterior to the posterior M6, without covering the central M6 retinotopic field (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Directional M6-LNs. A: A single directional M6-LN with axonal terminals labeled by Syt::HA at the posterior (arrows, colocalized as white), but not anterior (asterisk), branches. Cell body is indicated by arrowhead. B: Four variants of directional M6-LNs. In A,B, brains are immunostained with anti-DLG. Arrowheads indicate cell bodies. C: Merged skeletal models of the four directional M6-LNs in B illustrate the coverage of M6 retinotopic columns by individual neurons; innervation patterns in anterior and posterior M6 domains are variable. Scale bars = 50 μm.

Variability of nondirectional M6-LNs

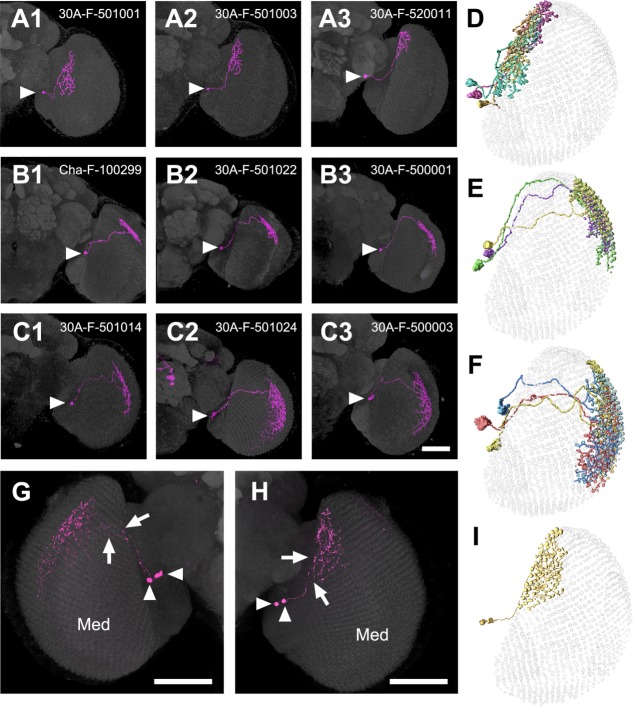

The nondirectional M6-LNs (n = 47) shared the common feature of spatially mixed dendrites and axons. These nondirectional M6-LNs were also highly variable in their morphology and spatial location. By aligning individual neurons with similar morphology into the common M6 retinotopic model, we found that nondirectional M6-LNs could be segregated into seven clusters, each cluster covering one distinct M6 subarea or domain (Fig. 5; in what follows, the seven clusters will be numbered 1–7 and neurons in them named as M6-LNn, where n is cluster number). Within each domain, individual neurons covered similar numbers, but different identities, of retinotopic columns, with extensive areal overlapping (Fig. 6A–C). Thus, together, but not individually, nondirectional M6-LNs with similar morphologies are likely covering all the retinotopic columns within each M6 domain (Fig. 6D–F). This is supported by the observation that arborizations from two sister M6-LN1s (Fig. 6G) or two sister M6-LN2s (Fig. 6H) in the same brain covered the same M6 domain as a single M6-LN1 (Fig. 5A) or a single M6-LN2 (Fig. 5B). We found that two sister M6-LN3s covered 91 columns in M6 (Fig. 6I), which is larger than but not twice as large as the coverage of a single of M6-LN3 (60.7 ± 5.0 columns; Table2), indicating a partial overlap and complementary coverage of retinotopic columns.

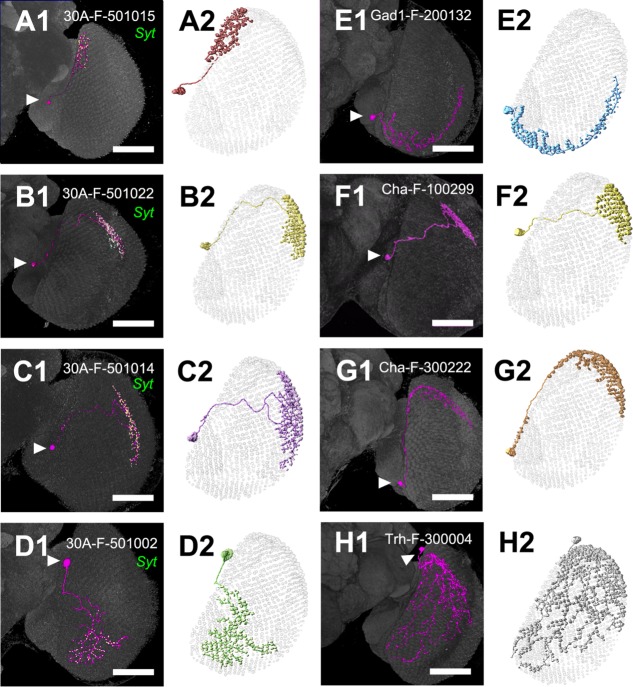

Figure 5.

Nondirectional M6-LNs. A: M6-LN1. B,F: M6-LN2. C: M6-LN3. D: M6-LN4. E: M6-LN5. G: M6-LN6. H: M6-LN7. A1–D1: Single nondirectional M6-LNs (magenta) with axonal terminals labeled by Syt::HA (green). E1–G1: Single nondirectional M6-LNs derived from the FlyCircuit database. Arrowhead indicates cell body. Brains are immunostained with anti-DLG (gray). The skeletal models in A2–H2 illustrate the coverage of the M6 retinotopic columns by each LN. Scale bars = 50 μm.

Figure 6.

Variability and domain specificity of nondirectional M6-LNs. A: M6-LN1. B: M6-LN2. C: M6-LN3. Cell bodies are indicated by arrowheads. D: Merged skeletal models of the three M6-LN1s shown in A1–3. E: Merged skeletal models of the three M6-LN2s shown in B1–3. F: Merged skeletal models of the three M6-LN3s shown in C1–3. Nondirectional M6-LNs innervating the same domain show similar global distributions, grouped cell bodies, and overlapping and complementary coverage of the M6 retinotopic columns. G: Two-cell clones of M6-LN2. H: Two-cell clones of M6-LN1. I: Skeletal models of the two sister M6-LN1s in G show overlapped and complementary coverage of 91 retinotopic columns in the same M6 domain. Arrowheads indicates cell body. Arrows indicates primary neurite. Med, medulla. Scale bars = 50 μm.

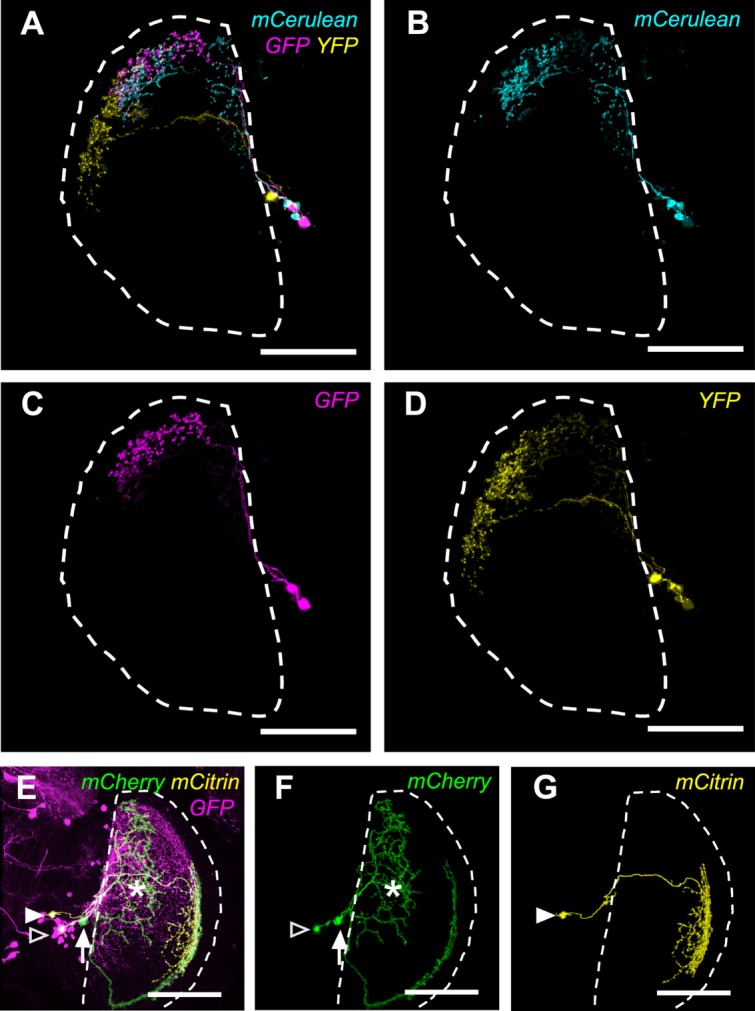

Using Brainbow 2.1R-2 to label a majority of Gal4 neurons in the same brain in different colors, we confirmed that the dorsal-posterior domain is covered by complementary innervations of multiple M6-LN2s (Fig. 7A) that are restricted within the same domain (Fig. 7B,C). Using Flybow to label a few Gal4 neurons in the same brain in different colors (Hadjieconomou et al., 2011), we confirmed that directional (Fig. 7F) and nondirectional (Fig. 7G) M6-LNs coexisted in the same brain (Fig. 7E).

Figure 7.

Multicolor labeling of M6-LNs in the same brain. A: Brainbow shows combinatory labeling of M6-LNs. B: An M6-LN1 and an M6-LN2. C: Two M6-LN2s. D: A single M6-LN3. Genotype: w,UAS-Brainbow2.1R-2;30A-GAL4/hs-CRE-HA. E: Flybow labels the whole expression pattern. F: Directional M6-LN (arrow) and nondirectional M6-LN (open arrowhead) with putative dendritic arborizations at the anterior M6 (asterisk). G: A nondirectional M6-LN3 (solid arrowhead). Genotype: 30A-GAL4/UAS-FB1.1260;+/hs-mFlp5. Dashed line sketches the boundary of the medulla. Scale bars = 50 μm.

M6-LN neurotransmitters

Next, we showed that the two M6-LN families differ in their neurotransmitter types, using immunostaining with three different antibodies: anti-GABA for putative GABAergic neurons, anti-DVGLUT for putative glutamatergic neurons, and anti-5HT for putative serotonergic neurons (Fig. 8). We found that most 30A-GAL4 neurons with cell bodies at the ventral LCBR and fibers at dorsal M6 are anti-GABA immunopositive. Some cell bodies at the dorsal and medial LCBR were also anti-GABA immunopositive (Fig. 8A). MARCM imaging of single-cell clones with Syt::HA labeling confirmed that nondirectional M6-LNs with cell bodies at the ventral LCBR, and mixed pre- and postsynaptic label at dorsal M6 were anti-GABA immunopositive (Fig. 8B).

Figure 8.

Neurotransmitters of M6-LNs in 30A-GAL4. A: Cell bodies at the dorsal (A1), medial (A2), and ventral (A3) LCBR are labeled by GFP (green) and immunostained by three different antibodies (magenta). Dorsal and ventral M6-LN cell bodies are anti-GABA immunopositive (solid arrowheads) but anti-DVGLUT immunonegative (open arrowheads). Medial M6-LN cell bodies are anti-DVGLUT immunopositive (solid arrowheads). All M6-LN cell bodies are anti-5HT immunonegative (open arrowheads). B: MARCM clones of five nondirectional M6-LNs. Syt::HA-positive terminals (magenta) and Syt::HA-negative terminals (green) are mixed. Insets: The nondirectional M6-LNs (green) in B are anti-GABA immunopositive (magenta). C: Anti-DVGLUT immunostaining at posterior M6. A representative optical section (1 μm in thickness) shows colocalization (solid arrowheads) between M6-LN boutons (green) and anti-DVGLUT-immunopositive signals (magenta). D: The remaining M6-LN boutons after Cha-GAL80 inhibition are anti-DVGLUT immunonegative (open arrowheads). E: Cha-GAL80 inhibition eliminates all anti-DVGLUT-immunopositive cell bodies but not anti-GABA-immunopositive cell bodies. Cell bodies at dorsal (E1), medial (E2), and ventral (E3) LCBR are labeled by GFP (green) and immunostained by two different antibodies (magenta). Genotypes: 1) UAS-mCD8::GFP;+/30A-GAL4 (B,C) and 2) FRT19A,UAS-mCD8::GFP;+/30A-GAL4;+/Cha-GAL80 (D,E). Scale bars = 10 μm.

The medulla contains abundant anti-DVGLUT-immunopositive fibers (Daniels et al., 2008). We found that some 30A-GAL4 neurons with their cell bodies at the medial LCBR (Fig. 8A) and fibers in the M6 (Fig. 8C) are anti-DVGLUT immunopositive (n = 3). In the presence of Cha-GAL80 inhibition, the remaining 30A-GAL4 neurons were mostly anti-DVGLUT immunonegative (Fig. 8D,E) but were all anti-GABA immunopositive (Fig. 8E). Together, these results suggest that directional M6-LNs in 30A-GAL4 are Cha-GAL80 positive, anti-DVGLUT immunopositive, and anti-GABA immunonegative. Additionally, at least some nondirectional M6-LNs are Cha-GAL80 negative, anti-DVGLUT immunonegative, and anti-GABA immunopositive. All cell bodies of 30A-GAL4 neurons at LCBR were anti-5HT immunonegative (Fig. 8A).

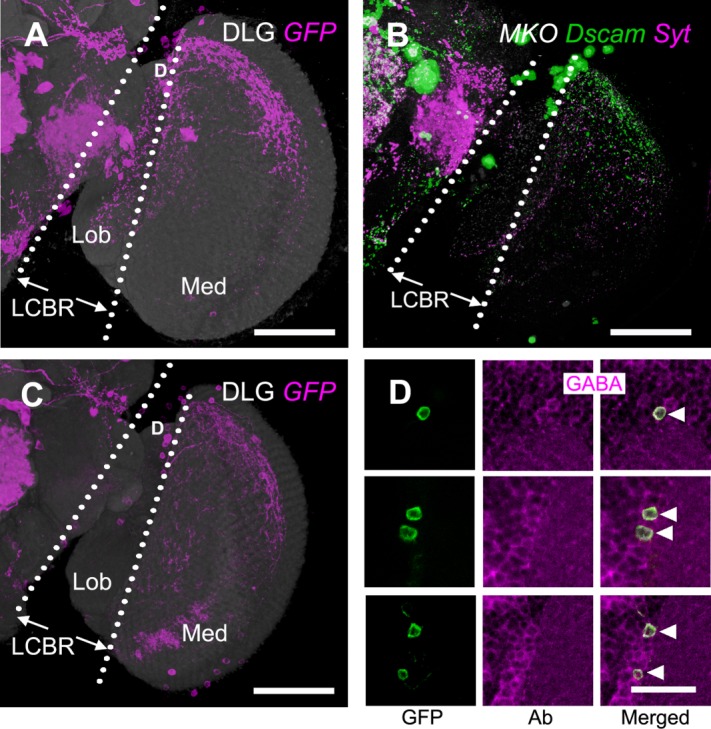

Confirming diversity and variability

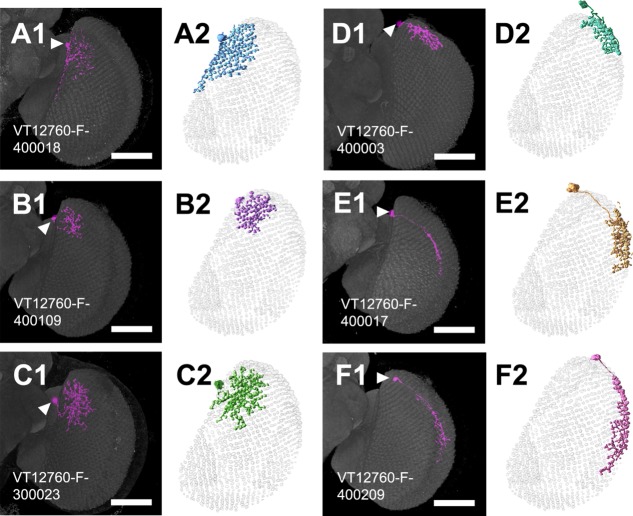

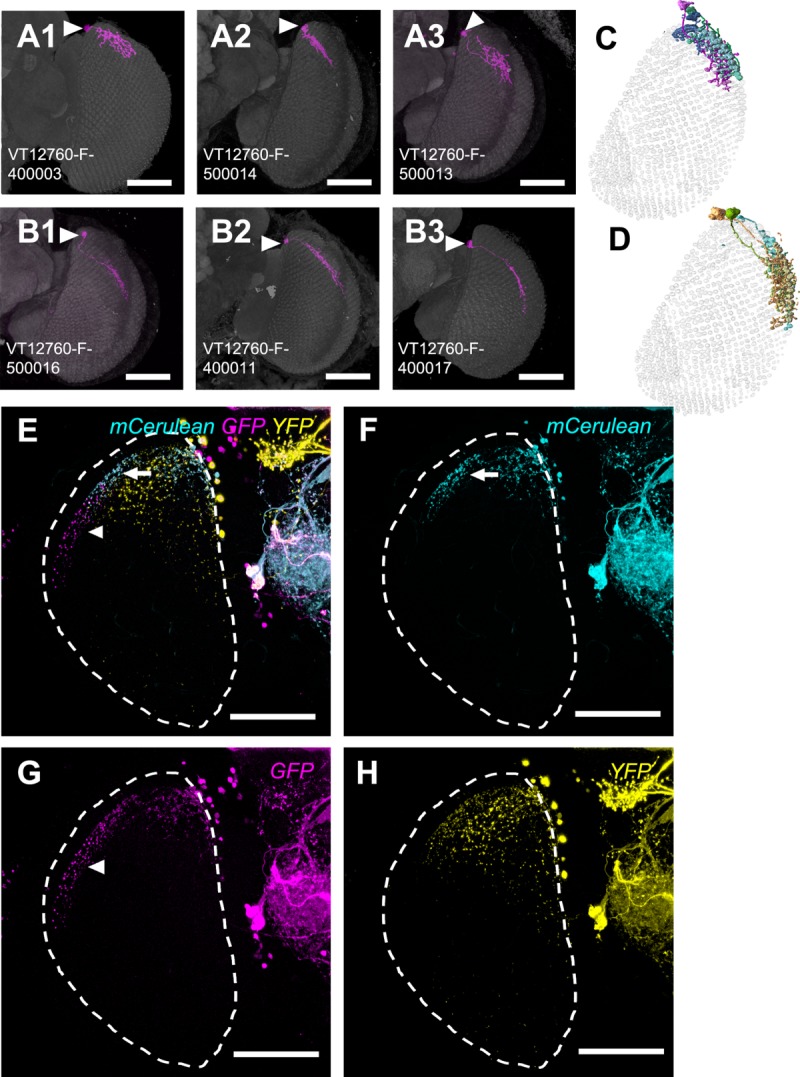

We identified an independent Gal4 line, VT12760-GAL4, that showed GAL4 expression in only the nondirectional M6-LNs in the optic lobes. Compared with M6-LNs in the 30A-GAL4, those in the VT12760-GAL4 projected dense fibers to the anterior-dorsal and posterior edges but not the center field of M6 (Fig. 9A; n = 12). The terminals of putative dendrites and axons labeled by Dscam::GFP and Syt::HA, respectively, were small and mixed but did not colocalize (Fig. 9B), suggesting that VT12760-GAL4 expresses only nondirectional M6-LNs. This was confirmed by the following findings: 1) Cha-GAL80 inhibition reduced expression in the central brain (showing that the test was valid) but not in the anterior-dorsal and posterior edges of M6 (Fig. 9C) and 2) M6-LNs in the VT12760-GAL4 were all anti-GABA immunopositive (Fig. 9D). MARCM imaging collected at least six additional clusters of nondirectional M6-LNs (Fig. 10, Table12; n = 33). In addition, individual M6-LNs in the same cluster covered a similar number of retinotopic columns, with extensive areal overlapping between their axonal arbors, but made different choices for which specific columns to innervate (Fig. 11A,B). Combining several M6-LNs of the same cluster to the common M6 volume model showed that each cluster covered one distinct M6 domain (Fig. 11C,D). Brainbow labeling of multiple VT12760-GAL4 neurons with different colors in the same brain confirmed that M6-LNs exhibit individual variability limited within the same domain and domain specificity between different clusters (Fig. 11E–H).

Figure 9.

M6-LNs in VT12760-GAL4. A: Expression pattern of VT12760-GAL4 (magenta). M6-LNs cell bodies are located at the dorsal (D) LCBR. The brain is immunostained with anti-DLG (gray). B: Polarity labeling with presynaptic marker Syt::HA (magenta) and postsynaptic marker Dscam-GFP (green) in the M6-LNs labeled by MKO (gray). C: VT12760-GAL4 expression pattern subjected to Cha-GAL80 inhibition (magenta). The brain is immunostained with anti-DLG (gray). D: Remaining cell bodies of M6-LNs in VT12760-GAL4 after Cha-GAL80 inhibition (green) are all anti-GABA (magenta) immunopositive (arrowheads). LCBR, lateral cell body rind; Med, medulla; Lob, lobula. Scale bars = 50 μm in A–C; 10 μm in D.

Nondirectional M6-LNs in VT12760-GAL4. A: M6-LN8. B: M6-LN9. C: M6-LN10. D: M6-LN11. E: M6-LN12. F: M6-LN13. A1–F1: MARCM labeling of single nondirectional M6-LNs (magenta). Arrowhead indicates the cell body. Brains are immunostained with anti-DLG (gray). The skeletal models in A2–F2 illustrate coverage of the M6 retinotopic columns by each LN. Scale bars = 50 μm.

Figure 11.

Variability and domain specificity of nondirectional M6-LNs in VT12760-GAL4. A: Variability of nondirectional M6-LN11. B: Variability of nondirectional M6-LN12. C: Merged skeletal models of three M6-LN11s. D: Merged skeletal models of three M6-LN12s. LNs in the same cluster show domain-specific distribution, grouped cell bodies, and overlapping and complementary innervations of the M6 retinotopic columns. Arrowhead indicates the cell body. E: Brainbow labeling of M6-LNs in VT12760-GAL4. F: M6-LN12 (arrow). G: M6-LN13 (arrowhead). H: M6-LN8 and M6-LN10. Genotype: w,UAS-Brainbow2.1R-2;+/hs-CRE-HA;VT12760-GAL4/+. Scale bars = 50 μm.

DISCUSSION

Several lines of evidence indicate that medulla M6 stratum contains at least two distinct families of LNs, directional and nondirectional neurons. First, using MARCM labeling, we visualized hundreds of single LNs with arborizations restricted within the M6 stratum (Figs. 4-6, 10, 11, Supp. Info. Movie 2). These M6-LNs exhibited a great degree of variability in cell body location, retinotopic coverage, and spatial distribution (Table2). Second, polarity analysis showed that these M6-LNs could be classified into two families, directional neurons with segregated axons and dendrites and nondirectional neurons with mixed axons and dendrites (Figs. 3, 9). Third, multicolor labeling with Brainbow and Flybow revealed that individual M6-LNs in the two families are highly variable in their spatial distribution and coexist in the same brain (Figs. 7, 1). Fourth, neurotransmitter immunolabeling showed that some directional neurons are anti-DVGLUT immunopositive, and some nondirectional neurons are anti-GABA immunopositive (Figs. 8, 9), but not vice versa. Fifth, Cha-Gal80 inhibits Gal4 expression in directional (Figs. 3C,D, 8D) but not in nondirectional M6-LNs (Figs. 8E, 9C). Sixth, M6-LNs in 30A-GAL4 are directional or nondirectional but in VT12760-GAL4 are exclusively nondirectional. Together, our data reveal a complex local network for visual information processing within the medulla M6 stratum.

Retinotopic representation at M6

UV polarization information is sent by Rh3-positive neurons in the DRA ommatidia to the medulla (Strausfeld and Wunderer, 1985; Fortini and Rubin, ,; Wernet et al., ,). Although most columns in the M6 retinotopic field are terminated only by R7, our results suggest that the enlarged columns at the M6 dorsal-posterior edge consist of dual terminals derived from Rh3-LexA-positive R7s and Rh6-GAL4-positive R8s, respectively (Fig. 2F,H–L). Genetic manipulation of Hth expression confirmed that the dual terminals originate from the photoreceptor neurons in the DRA (Figs. 2M,N, 12A). Nevertheless, DRA R7s and R8s are both Rh3-antibody immunopositive (Mazzoni et al., 2008). One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that Rh3-LexA and Rh6-GAL4 drivers report the neuron type but not the opsin type. Alternatively, there might be two subsets of DRA R8s with different layer specificity, i.e., Rh3-positive R8s terminating at M3 and Rh6-positive R8s terminating at M6.

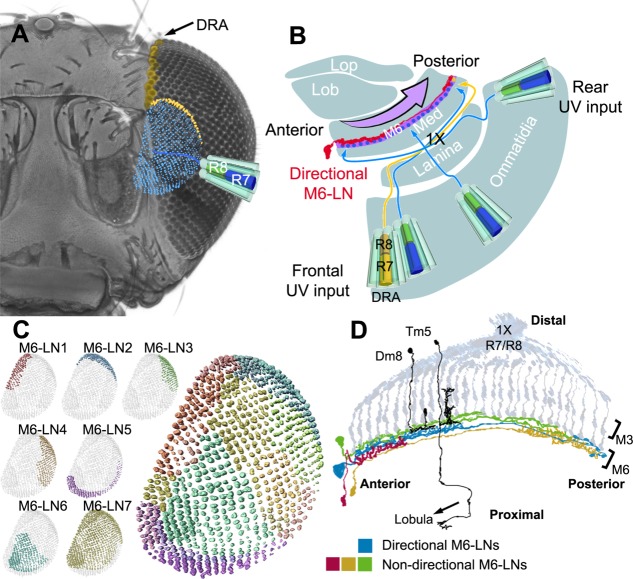

Directional M6-LNs

Directional M6-LNs in 30A-GAL4 were found to be anti-DVGLUT immunopositive (Fig. 8C–E) and Cha-GAL80 positive (Fig. 3B,D). These directional M6-LNs may be excitatory or inhibitory depending on whether downstream neurons express ionotropic or metabotropic glutamate receptors. However, directional LNs are not unusual in the fly brain. For example, all Kenyon cells forming the mushroom body are directional, with dendrites receiving olfactory information from the calyx and axons sending information to the output neurons innervating different lobes (Ito et al., 1997; Strausfeld et al., 2003). Similar directional LNs also exist in the antennal lobe, where most LNs are nondirectional but some oligoglomerular LNs have a selective synaptotagmin-HA distribution (Chou et al., 2010), suggesting directional information flow between glomeruli. In the protocerebral bridge, all LNs are directional, with a highly ordered pattern of innervation among different glomeruli, suggesting information integration and reiteration (Lin et al., 2013). If Rh6-GAL4-positive R8s and Rh3-immunopositive R8s at DRA are assumed to be the same, we can speculate that frontal UV inputs from R7 and polarized UV signals from DRA R7/R8 are converged at the dorsal-posterior M6 domain, where they integrate with rear visual signals relayed by directional M6-LNs (Fig. 12B). It will be interesting to determine whether directional M6-LNs pointing in the opposite direction exist for visual information integration and reiteration, similar to those in the protocerebral bridge, and how the directionality of information flow in M6 affects the fly's polarotaxis and phototaxis behavior. A more comprehensive anatomical mapping of M6-LNs and other layer-specific LNs will help us to understand why the fly has a better phototactic response to UV than to visible light (Hu and Stark, 1977).

Figure 12.

Schematic representation of UV vision in the M6 stratum. A: Retinotopic representation of UV-sensitive neurons in the M6 stratum. Each of approximately 800 R7 neurons relays UV information along one column to terminate at the M6 stratum, forming a UV retinotopic map (blue). The UV polarization-detecting DRA neurons (yellow) project to the dorsal-lateral M6 stratum. B: Top view of the left optic lobe shows chiasmatic information relay (×1) from frontal and rear ommatidia to posterior and anterior M6, respectively. Directional M6-LNs (red) relay information from the anterior to the posterior M6 (arrow). Med, medulla; Lob, lobula; Lop, lobula plate. C: Innervation territories of nondirectional M6-LN clusters (shown in different colors) form a mosaic of seven domains, covering the whole M6 retinotopic field. D: Functional motif in the M6 stratum: R7/R8 input neurons, narrow-field output projection neurons (black; i.e., Dm8 to the M4 stratum and Tm5 to the lobula), nondirectional LNs (green, red, and orange), and directional M6-LNs (blue).

Nondirectional M6-LNs

By aligning 72 single neurons derived from different brains to the common M6 volume model and by Brainbow labeling multiple neurons in the same brain, we showed that nondirectional M6-LNs are highly variable in their morphology and spatial distribution but could be grouped into distinct clusters, each cluster covering a specific M6 domain (Figs. 5, 6, 10). Analysis of two independent Gal4 drivers, 30A-GAL4 (Fig. 5) and VT12760-GAL4 (Fig. 10), showed that individual nondirectional M6-LNs are highly variable with regard to retinotopic innervation. Nevertheless, M6-LNs in each Gal4 line always covered the same domains of the retinotopic field in different brains. Together, these results suggest that nondirectional M6-LNs show local variability but global stereotypy. Combining all 72 identified nondirectional M6-LNs into the common M6 volume model covers only the dorsal half of the M6 retinotopic field (Fig. 12C, Table2). These dorsal M6-LNs identified in the current study together with the ventral M6-LNs (i.e., M6-LN5, M6-LN6, and M6-LN7) found in the FlyCircuit database form a mosaic distribution over the retinotopic map in which each tile is the unique innervation domain of exactly one LN cluster (Fig. 2C). However, some ventral M6-LNs derived from the FlyCircuit database have only one example (Table2), and their neurotransmitters are unclear. Further studies of specific Gal4 drivers expressed in the ventral M6-LNs are necessary to determine whether specifically GABAergic M6-LNs cover the entire M6 retinotopic field.

Because many, if not all, of these nondirectional M6-LNs are anti-GABA immunopositive (Figs. 8, 9), it is tempting to speculate that such a domain-specific inhibitory local field might be useful in preventing signal saturation from a bright spot, without compromising sensitivity to the surrounding visual field. Alternatively, such domain-specific inhibition in the visual field could serve as lateral inhibition in sharpening the input signal, similarly to the role of medium-field amacrine cells in the vertebrate retina (Werblin, 2011).

Information integration

For Drosophila, three classes of medulla neurons have been previously described, 1) medulla intrinsic neurons (Mi) that connect the distal with the proximal medulla neuropil, 2) distal medulla amacrine cells (Dm) that arborize exclusively in the distal medulla, and 3) proximal medulla amacrine cells (Pm) that branch exclusively in the proximal medulla (Fischbach and Dittrich, 1989). At the single-cell level, each of these types innervates specific medulla layers and exhibits diverse sizes of field coverage within each layer (Fischbach and Dittrich, 1989; Bausenwein et al., 1992; Bausenwein and Fischbach, 1992; Morante and Desplan, 2008).

At the M6 stratum, the dendrites of narrow-field projection neurons (i.e., Dm8 and Tm5) receive UV inputs from fewer than 20 columns of R7/R8 terminals (Fischbach and Dittrich, 1989; Gao et al., 2008), whereas wide-field Mt11 neurons may cover more than 20 columns (Fischbach and Dittrich, 1989). Golgi staining has identified additional M6 projection neurons such as Dm2, Dm5-like, Mi3, Mt11-like, Tm5a, Tm5b, Tm5c, TmY5a, and TmY10 (Fischbach and Dittrich, 1989). Three-dimensional reconstruction from serial-section transmission electron microscopy has confirmed most of the previous findings and revealed several additional M6 projection neurons, including Unknown Tm-1, 3, 7, 8, 9, 12, 13, 14, 16, and 17 (Takemura et al., 2013). At least some of these M6 projection neurons have been implicated in visual processing and behavior (Gao et al., 2008; Karuppudurai et al., 2014; Otsuna et al., 2014).

A local processing unit (LPU) is a brain region that contains its own populations of LNs, with their dendrites and axons both restricted within this region, and that connects to other brain regions via projection neurons with axons organized in tracts (Chiang et al., 2011). The diversity (directional vs. nondirectional families) and variability (individual differences in retinotopic coverage) of M6-LNs revealed by the current study, however incompletely, imply another level of complexity in visual information processing, suggesting that M6 may act as an LPU for UV vision. Intriguingly, except for a few long-form R7 terminals, most R7 terminals locate close to, but separate from, M6-LN fibers. Specific contact with long-form, but not short-form, R7s is consistent with the results of the previous Golgi study showing two potential R7 subtypes terminating at different depths in the medulla (Fischbach and Dittrich, 1989). This observation is of potential interest because it implies subdivision of R7s into two morphologically and functionally distinct types.

We speculate that the Drosophila M6 stratum is constructed from a small, modular synaptic interaction motif consisting of visual input (R7/R8), output (Dm8/Tm5 and others), and local (M6-LNs) neurons, repeated across the entire M6 retinotopic field underlying visual functionality (Fig. 2D). In addition, nondirectional GABAergic M6-LNs might synapse mostly with M6 output neurons, serving as lateral inhibition to sharpen the output signal. It remains to be shown whether such a hypercircuit exists in other medulla strata and whether the insect medulla is actually subdivided into multiple LPUs, one for each stratum, in a manner similar to that observed in the vertebrate inner plexiform layer (Werblin, 2011), to provide multiple, differently specialized representations of the visual world. Comparisons between different medulla strata in Drosophila may uncover the basic operating principles of a hypercircuit and help us to understand visual information processing in higher organisms.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jens Rister, Claude Desplan, Richard Axel, Tzumin Lee, Kristin Scott, and the Bloomington Stock Center for providing transgenic flies and Aaron DiAntonio for sharing anti-DVGLUT serum with us. We also thank the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB) for the 4F3 anti-Discs large antibodies and the Taiwan National Center for High-performance Computing (NCHC) for the FlyCircuit database images.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ROLE OF AUTHORS

A-LC and A-SC had full access to all study data, and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analysis. Study concept and design: A-LC, A-SC. 3D model generation: A-LC, C-YL. Acquisition of data: A-LC, C-YL. Analysis and interpretation of data: A-LC, A-SC. Drafting the manuscript: A-LC, A-SC.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Movie 1. Procedures for the generation of the M6 retinotopic map. The M6 stratum is segmented from the DLG-immunostained standard brain (gray). Isolating the intersection of all photoreceptor neurons (green) expressing glass multiple reporter (GMR) with the M6 volume model (magenta) results in a retinotopic map representing R7/R8 terminals (blue) in the M6 stratum.

Movie 2. Skeleton views of 57 individual M6-LNs. All axons and dendrites of these M6-LNs are confined to the M6 stratum, suggesting that the M6 stratum acts as an independent LPU. Each color represents a distinct neuron. Gray: Medulla, lobula, and lobula plate.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Bausenwein B, Fischbach KF. Activity labelings patterns in the medulla of Drosophila melanogaster caused by motion stimuli. Cell Tissue Res. 1992;270:25–35. doi: 10.1007/BF00381876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bausenwein B, Dittrich APM, Fischbach KF. The optic lobe of Drosophila melanogaster. II. Sorting of retinotopic pathways in the medulla. Cell Tissue Res. 1992;267:17–28. doi: 10.1007/BF00318687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiang AS, Lin CY, Chuang CC, Chang HM, Hsieh CH, Yeh CW, Shih CT, Wu JJ, Wang GT, Chen YC, Wu CC, Chen GY, Ching YT, Lee PC, Lin CY, Lin HH, Wu CC, Hsu HW, Huang YA, Chen JY, Chiang HJ, Lu CF, Ni RF, Yeh CY, Hwang JK. Three-dimensional reconstruction of brain-wide wiring networks in Drosophila at single-cell resolution. Curr Biol. 2011;21:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chou YH, Spletter ML, Yaksi E, Leong JCS, Wilson RI, Luo L. Diversity and wiring variability of olfactory local interneurons in the Drosophila antennal lobe. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:439–449. doi: 10.1038/nn.2489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniels RW, Collins CA, Gelfand MV, Dant J, Brooks ES, Krantz DE, DiAntonio A. Increased expression of the Drosophila vesicular glutamate transporter leads to excess glutamate release and a compensatory decrease in quantal content. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10466–10474. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3001-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daniels RW, Collins CA, Chen K, Gelfand MV, Featherstone DE, DiAntonio A. A single vesicular glutamate transporter is sufficient to fill a synaptic vesicle. Neuron. 2006;49:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daniels RW, Gelfand MV, Collins CA, DiAntonio A. Visualizing glutamatergic cell bodies and synapses in Drosophila larval and adult CNS. J Comp Neurol. 2008;508:131–152. doi: 10.1002/cne.21670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enell L, Hamasaka Y, Kolodziejczyk A, Nassel DR. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) signaling components in Drosophila: immunocytochemical localization of GABAB receptors in relation to the GABAA receptor subunit RDL and a vesicular GABA transporter. J Comp Neurol. 2007;505:18–31. doi: 10.1002/cne.21472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Famiglietti EV, Jr, Kolb H. Structural basis for ON- and OF-center responses in retinal ganglion cells. Science. 1976;194:193–195. doi: 10.1126/science.959847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischbach KF, Dittrich APM. The optic lobe of Drosophila melanogaster. I. A Golgi analysis of wild-type structure. Cell Tissue Res. 1989;258:441–475. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fortini ME, Rubin GM. Analysis of cis-acting requirements of the Rh3 and Rh4 genes reveals a bipartite organization to rhodopsin promoters in Drosophila melanogaster. Genes Dev. 1990;4:444–463. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.3.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fortini ME, Rubin GM. The optic lobe projection pattern of polarization-sensitive photoreceptor cells in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Tissue Res. 1991;265:185–191. doi: 10.1007/BF00318153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freeman M. Reiterative use of the EGF receptor triggers differentiation of all cell types in the Drosophila eye. Cell. 1996;87:651–660. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81385-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao S, Takemura SY, Ting CY, Huang S, Lu Z, Luan H, Rister J, Thum AS, Yang M, Hong ST, Wang JW, Odenwald WF, White BH, Meinertzhagen IA, Lee CH. The neural substrate of spectral preference in Drosophila. Neuron. 2008;60:328–342. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hadjieconomou D, Rotkopf S, Alexandre C, Bell DM, Dickson BJ, Salecker I. Flybow: genetic multicolor cell labeling for neural circuit analysis in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat Methods. 2011;8:260–266. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamanaka Y, Meinertzhagen IA. Immunocytochemical localization of synaptic proteins to photoreceptor synaptic proteins to photoreceptor synapses of Drosophila melanogaster. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:1133–1155. doi: 10.1002/cne.22268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardie RC. Properties of photoreceptors R7 and R8 in dorsal marginal ommatidia in the compound eyes of Musca and Calliphora. J Comp Physiol A. 1984;154:157–165. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu KG, Stark WS. Specific receptor input into spectral preference in Drosophila. J Comp Physiol A. 1977;121:241–252. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huser A, Rowedder A, Apostolopoulou AA, Widmann A, Pfitzenmaier JE, Maiolo EM, Selcho M, Pauls D, von Essen A, Gupta T, Sprecher SG, Birman S, Riemensperger T, Stocker RF, Thum AS. The serotonergic central nervous system of the Drosophila larva: anatomy and behavioral function. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47518. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ito K, Awano W, Suzuki K, Hiromi Y, Yamamoyo D. The Drosophila mushroom body is a quadruple structure of clonal units each of which contains a virtually identical set of neurons and glial cells. Development. 1997;124:761–771. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.4.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jefferis GS, Potter CJ, Chan AM, Marin EC, Rohlfing T, Maurer CR, Jr, Luo L. Comprehensive maps of Drosophila higher olfactory centers: spatially segregated fruit and pheromone representation. Cell. 2007;128:1187–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karuppudurai T, Lin TY, Ting CY, Pursley R, Melnattur KV, Diao F, White BH, Macpherson LJ, Gallio M, Pohida T, Lee CH. A hard-wired glutamatergic circuit pools and relays UV signals to mediate spectral preference in Drosophila. Neuron. 2014;81:603–615. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kitamoto T. Conditional disruption of synaptic transmission induces male–male courtship behavior in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13232–13237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202489099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolodziejczyk A, Sun X, Meinertzhagen IA, Nassel DR. Glutamate, GABA, and acetylcholine signaling components in the lamina of the Drosophila visual system. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuo SY, Tu CH, Hsu YT, Wang HD, Wen RK, Lin CT, Wu CL, Huang YT, Huang GS, Lan TH, Fu TF. A hormone receptor-based transactivator bridges different binary systems to precisely control spatial-temporal gene expression in Drosophila. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50855. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Labhart T, Meyer EP. Detectors for polarized skylight in insects: a survey of ommatidial specializations in the dorsal rim area of the compound eye. Microsc Res Techniq. 1999;47:368–379. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19991215)47:6<368::AID-JEMT2>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lahey T, Gorczyca M, Jia XX, Budnik V. The Drosophila tumor suppressor gene dlg is required for normal synaptic bouton structure. Neuron. 1994;13:823–835. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90249-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lai JS, Lo SJ, Dickson BJ, Chiang AS. Auditory circuit in the Drosophila brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:2607–2612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117307109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee CH, Herman T, Clandinin TR, Lee R, Zipursky SL. N-cadherin regulates target specificity in the Drosophila visual system. Neuron. 2001;30:437–450. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00291-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee T, Luo L. Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker for studies of gene function in neuronal morphogenesis. Neuron. 1999;22:451–461. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80701-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lehnert BP, Baker AE, Gaudry Q, Chiang AS, Wilson RI. Distinct roles of TRP channels in auditory transduction and amplification in Drosophila. Neuron. 2013;77:115–128. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li W, DeVries SH. Bipolar cell pathways for color and luminance vision in a dichromatic mammalian retina. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:669–675. doi: 10.1038/nn1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin CY, Chuang CC, Hua TE, Chen CC, Dickson BJ, Greenspan RJ, Chiang AS. A comprehensive wiring diagram of the protocerebral bridge for visual information processing in the Drosophila brain. Cell Rep. 2013;3:1739–1753. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Livet J, Weissman TA, Kang H, Draft RW, Lu J, Bennis RA, Sanes JR, Lichtman JW. Transgenic strategies for combinatorial expression of fluorescent proteins in the nervous system. Nature. 2007;450:56–62. doi: 10.1038/nature06293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacNeil MA, Masland RH. Extreme diversity among amacrine cells: implications for function. Neuron. 1998;20:971–982. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80478-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacNeil MA, Heussy JK, Dacheux RF, Raviola E, Masland RH. The shapes and numbers of amacrine cells: matching of photofilled with Golgi-stained cells in the rabbit retina and comparison with other mammalian species. J Comp Neurol. 1999;413:305–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mazzoni EO, Celik A, Wernet MF, Vasiliauskas D, Johnston RJ, Cook TA, Pichaud F, Desplan C. Iroquois complex genes induce co-expression of rhodopsins in Drosophila. PLoS Biol. 2008;22:e97. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meinertzhagen IA, Sorra KE. Synaptic organization in the fly's optic lamina: few cells, many synapses and divergent microcircuits. Prog Brain Res. 2001;131:53–69. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(01)31007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mikeladze-Dvali T, Wernet MF, Pistillo D, Mazzoni EO, Teleman AA, Chen YW, Cohen S, Desplan C. The growth regulators warts/lats and melted interact in a bistable loop to specify opposite fates in Drosophila R8 photoreceptors. Cell. 2005;122:775–787. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morante J, Desplan C. Building a projection map for photoreceptor neurons in the Drosophila optic lobes. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2004;15:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morante J, Desplan C. The color-vision circuit in the medulla of Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2008;18:553–565. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.02.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Olsen SR, Wilson RI. Lateral presynaptic inhibition mediates gain control in an olfactory circuit. Nature. 2008;452:956–960. doi: 10.1038/nature06864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Olsen SR, Bhandawat V, Wilson RI. Excitatory interactions between olfactory processing channels in the Drosophila antennal lobe. Neuron. 2007;54:89–103. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Otsuna H, Shinomiya K, Ito K. Parallel neural pathways in higher visual centers of the Drosophila brain that mediate wavelength-specific behavior. Front Neural Circuits. 2014;10:8. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2014.00008. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2014.00008. eCollection 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park J, Lee SB, Lee S, Kim Y, Song S, Kim S, Bae E, Kim J, Shong M, Kim JM, Chung J. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Drosophila PINK1 mutants is complemented by parkin. Nature. 2006;441:1157–1161. doi: 10.1038/nature04788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parnas D, Haghighi AP, Fetter RD, Kim SW, Goodman CS. Regulation of postsynaptic structure and protein localization by the Rho-type guanine nucleotide exchange factor dPix. Neuron. 2001;32:415–424. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00485-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raghu SV, Borst A. Candidate glutamatergic neurons in the visual system of Drosophila. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19472. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Raghu SV, Reiff DF, Borst A. Neurons with cholinergic phenotype in the visual system of Drosophila. J Comp Neurol. 2011;519:162–176. doi: 10.1002/cne.22512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raghu SV, Claussen J, Borst A. Neurons with GABAergic phenotype in the visual system of Drosophila. J Comp Neurol. 2013;521:252–265. doi: 10.1002/cne.23208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rister J, Pauls D, Schnell B, Ting CY, Lee CH, Sinakevitch I, Morante J, Strausfeld NJ, Ito K, Heisenberg M. Dissection of the peripheral motion channel in the visual system of Drosophila melanogaster. Neuron. 2007;56:155–170. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roska B, Werblin FS. Vertical interactions across ten parallel, stacked representations in the mammalian retina. Nature. 2001;410:583–587. doi: 10.1038/35069068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roska B, Molnar A, Werblin F. Parallel processing in retinal ganglion cells: how integration of space–time patterns of excitation and inhibition form the spiking output. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:3810–3822. doi: 10.1152/jn.00113.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ryoo HD, Marty T, Casares F, Affolter M, Mann RS. Regulation of Hox target genes by a DNA bound Homothorax/Hox/extradenticle complex. Development. 1999;126:5137–5148. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.22.5137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sanes JR, Zipursky SL. Design principles of insect and vertebrate visual systems. Neuron. 2010;66:15–36. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Seki Y, Rybak J, Wicher D, Sachse S, Hansson BS. Physiological and morphological characterization of local interneurons in the Drosophila antennal lobe. J Neurophysiol. 2010;104:1007–1019. doi: 10.1152/jn.00249.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Strausfeld NJ, Wunderer H. Optic lobe projections of marginal ommatidia in Calliphora erythrocephala specialized for detecting polarized light. Cell Tissue Res. 1985;242:163–178. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Strausfeld NJ, Sinakevitch I, Vilinsky I. The mushroom bodies of Drosophila melanogaster: an immunocytological and Golgi study of Kenyon cell organization in the calyces and lobes. Microsc Res Techniq. 2003;62:151–169. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takemura SY, Lu Z, Meinertzhagen IA. Synaptic circuits of the Drosophila optic lobe: the input terminals to the medulla. J Comp Neurol. 2008;509:493–513. doi: 10.1002/cne.21757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takemrua SY, Bharioke A, Lu Z, Nern A, Vitaladevuni S, Rivlin PK, Katz WT, Olbris DJ, Plaza SM, Winston P, Zhao T, Horne JA, Fetter RD, Takemura S, Blazek K, Chang LA, Oqundeyi O, Saunders MA, Shapiro V, Siqmund C, Rubin GM, Scheffer LK, Meinertzhagen IA, Chklovskii DB. A visual motion detection circuit suggested by Drosophila connectomics. Nature. 2013;500:175–181. doi: 10.1038/nature12450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang J, Ma X, Yang JS, Zheng X, Zugates CT, Lee CH, Lee T. Transmembrane/juxtamembrane domain-dependent Dscam distribution and function during mushroom body neuronal morphogenesis. Neuron. 2004;43:663–672. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wassle H. Parallel processing in the mammalian retina. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:747–757. doi: 10.1038/nrn1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Werblin FS. The retinal hypercircuit: a repeating synaptic interactive motif underlying visual function. J Physiol. 2011;15:3691–3702. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.210617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wernet MF, Labhart T, Baumann F, Mazzoni EO, Pichaud F, Desplan C. Homothorax switches function of Drosophila photoreceptors from color to polarized light sensors. Cell. 2003;115:267–279. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00848-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wernet MF, Mazzoni EO, Çelik A, Duncan DM, Duncan I, Desplan C. Stochastic spineless expression creates the retinal mosaic for colour vision. Nature. 2006;440:174–180. doi: 10.1038/nature04615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wernet MF, Velez MM, Clark DA, Baumann-Klausener F, Brown JR, Klovstad M, Labhart T, Clandinin TR. Genetic dissection reveals two separate retinal substrates for polarization vision in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2012;22:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wilson RI, Laurent G. Role of GABAergic inhibition in shaping odor-evoked spatiotemporal patterns in the Drosophila antennal lobe. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9069–9079. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2070-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu SM, Gao F, Maple BR. Functional architecture of synapses in the inner retina: segregation of visual signals by stratification of bipolar cell axon terminals. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4462–4700. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-12-04462.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yasuyama K, Meinertzhagen IA. Extraretinal photoreceptors at the compound eye's posterior margin in Drosophila melanogaster. J Comp Neurol. 1999;412:193–202. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990920)412:2<193::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.