Abstract

For many insects, including mosquitoes, olfaction is the dominant modality regulating their behavioral repertoire. Many neurochemicals modulate olfactory information in the central nervous system, including the primary olfactory center of insects, the antennal lobe. The most diverse and versatile neurochemicals in the insect nervous system are found in the neuropeptides. In the present study, we analyzed neuropeptides in the antennal lobe of the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti, a major vector of arboviral diseases. Direct tissue profiling of the antennal lobe by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry indicated the presence of 28 mature products from 10 different neuropeptide genes. In addition, immunocytochemical techniques were used to describe the cellular location of the products of up to seven of these genes within the antennal lobe. Allatostatin A, allatotropin, SIFamide, FMRFamide-related peptides, short neuropeptide F, myoinhibitory peptide, and tachykinin-related peptides were found to be expressed in local interneurons and extrinsic neurons of the antennal lobe. Building on these results, we discuss the possible role of neuropeptide signaling in the antennal lobe of Ae. aegypti. J. Comp. Neurol. 522:592–608, 2014.

Keywords: olfaction, neuromodulation, mass spectrometry, immunocytochemistry, insect brain

Mosquitoes depend on a series of behaviors, including foraging, host seeking, and oviposition, for their survival and reproductive success (Clements, 1999). Each of these behaviors is mediated primarily by olfactory cues; these trigger a stereotypic response from the insect (Zwiebel and Takken, 2004). However, the ability to express a particular behavior is determined by age and physiological status, and is reflected in the function of the mosquito olfactory system (Zwiebel and Takken, 2004; Grant and O'Connell, 2007).

Many neurotransmitters and neuromodulators, including neuropeptides, are thought to play a key role in the regulation of plasticity in the insect olfactory system (Homberg and Müller, 1999; Schachtner et al., 2005; Nässel and Winther, 2010; Heuer et al., 2012). Mass spectrometry and immunocytochemical analyses have elucidated the processing and revealed the location of a variety of neuropeptides, e.g., A-type allatostatins (AST-As), allatotropins (ATs), FMRFamide-related peptides (FaRPs), and tachykinin-related peptides (TKRPs), in the primary olfactory center, the antennal lobe (AL), of insects (Homberg and Müller, 1999; Nässel, 2002; Schachtner et al., 2005; Utz et al., 2007; Nässel and Winther, 2010; Carlsson et al., 2010; Neupert et al., 2012). In fact, mass spectrometric profiling of cockroach ALs confirmed the presence of more than 50 neuropeptides, even in single AL glomeruli (Neupert et al., 2012). However, few studies of the functional role of neuropeptides in the insect olfactory system are available. Currently, these encompass analyses of TKRP and short neuropeptide F (sNPF) signaling in the AL of Drosophila melanogaster (Ignell et al., 2009; Winther and Ignell, 2010; Root et al., 2011).

In the mosquitoes Aedes aegypti and Culex salinarius, earlier immunocytochemical analysis indicated the expression of TKRPs in neuroendocrine cells that synapse with dendrites of olfactory sensory neuron (OSNs) (Meola et al., ,; Meola and Sittertz-Bhatkar, 2002). Furthermore, Ae. aegypti Head Peptide I (Aea-HP-I), acting as a humoral factor, has been shown to inhibit OSNs tuned to specific host cues (Stracker et al., 2002), and directly regulate the host-seeking behavior of female Ae. aegypti (Brown et al., 1994). Although these studies emphasized the key role of neuropeptides in regulating olfactory plasticity in mosquitoes, no comprehensive effort has been made to characterize neuropeptidergic expression in the mosquito olfactory system.

Here we profile the diversity of neuropeptides in the AL of the yellow fever mosquito, Ae. aegypti, using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry and immunocytochemical analyses. We demonstrate evidence for neuropeptides from 10 precursor genes. This study is intended as a foundation for future studies aimed at elucidating the function of neuropeptides in the regulation of odor-mediated behavioral plasticity in mosquitoes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mosquitoes

Two- to 7-day-old male and female Ae. aegypti mosquitoes (Rockefeller strain) were used in the present study. Mosquitoes were reared from larvae to adults at 27°C, 70–80% relative humidity and under a 12h:12h light:dark photoperiod, as described by Siju et al. (2008). Adult mosquitoes were housed in plastic cages with free access to 10% sugar solution.

MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry

Twenty ALs from females and males were prepared for mass spectrometric analysis according to the procedure described in Carlsson et al. (2010). After anesthetizing the insects by cooling, their brains were rapidly dissected from the head capsule in cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 0.3 M NaCl/0.01 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4). The ALs were then, under optic control (Zeiss Stereo Lumar V12), detached from the isolated brains using fine scissors. Each AL was then transferred onto a stainless steel MALDI-TOF sample plate using a glass capillary connected to a tube and a mouthpiece. Excessive PBS was immediately sucked off with the glass capillary. After being air-dried, the tissue spots were covered with a matrix solution using a nanoliter injector (World Precision Instruments, Berlin, Germany). The matrix solution, α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), was prepared as a saturated solution in methanol/ethanol/H2O/trifluoroacetic acid (30/30/39/1). Once dry, mass spectra were acquired by a Voyager 4800 plus MALDI TOF/TOF Analyzer (Applied Biosystems; Warrington, UK) in reflection mode within the mass range of 800–3,000 Da. Final mass spectra represent the average of 1,000 laser shots. Mass calibration was obtained by acquiring spectra from synthetic peptides of the calibration standard no. 206195 from Bruker Daltonics (Bremen, Germany; Angiotensin III: 931.515, Angiotensin II: 1046.542, Angiotensin I: 1296.685, ACTH (18–39): 2465.199). Data were analyzed with the software Data Explorer (v. 4.3, Applied Biosystems). Mass peaks were acknowledged only if they were above the intensity threshold (5% above baseline), with the background noise level being at most about 2% above baseline. In addition, signals above threshold were counted only if they showed the isotopic pattern typical of peptides.

Immunocytochemistry

Tissue preparation and immunostaining procedure

For the immunocytochemical analysis, we followed the protocol described by Siju et al. (2008). Briefly, mosquitoes were anesthetized on ice. After decapitation, heads were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C on a rotator. Following fixation, specimens were dissected in 0.01 M PBS containing 0.25% Triton-X solution (PBSTx) and washed several times for 5 hours at room temperature (RT). Specimens were then incubated overnight at 4°C in 0.01 M PBS with 4% Triton-X solution, washed in PBSTx, and placed in a blocking solution (2% bovine serum albumin) for 1 hour at RT. After being washed in PBSTx, the specimens were incubated with primary antiserum (see below) for 2 days at 4°C on a rotator. Subsequently, the specimens were washed several times in PBSTx and incubated with secondary goat antirabbit antiserum (IgG) conjugated to Alexa 488 (1:200), Cy3, or Cy5 (both 1:300, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) or with a secondary goat antimouse antiserum conjugated to Dylight 488 (1:300, Jackson ImmunoResearch) as well as the F-actin stain, Alexa Phalloidin 546 (1:100) diluted in dilution buffer (2% bovine serum albumin [BSA] in PBSTx), for 2 days at 4°C on a rotator. Specimens were washed repeatedly in PBSTx for 5 hours at RT and then mounted in Vectashield hard mount (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) to be viewed by confocal microscopy. Alternatively, brains were dehydrated in an ascending alcohol series (30–100%, 5 minutes each), cleared in methyl salicylate (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), and subsequently mounted in Permount (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ). Preabsorption of antisera with their respective antigens were carried out overnight at 4°C. Preabsorbed antigens were applied for immunocytochemistry as described above.

Primary antisera

The following polyclonal primary anti-peptide antibodies from rabbit were used (Table1): anti-AST-A (Diploptera punctata AST-7); anti-AT (Manduca sexta AT, No. 13.3.91); anti-SIFamide (D. melanogaster SIFa); anti-FMRFamide (No. 671N); anti-MIP (Periplaneta americana MIP); anti-sNPF (D. melanogaster sNPF-3); and anti-TKRP (Leucophaea maderae TKRP-1, code K 9836). In addition, a mouse monoclonal anti-synapsin antibody (anti-SYNORF1, 3C11, 1:50; kindly provided by E. Buchner, University of Würzburg, Germany) was used to counterstain background neuropil. The antibody recognized multiple isoforms on western blots in wildtype D. melanogaster, which disappeared in synapsin-null mutants (Klagges et al., 1996).

Table 1.

Overview of All Primary Antipeptide Antisera Used in This Study

| Antibody | Dilution | Immunogen | Reference | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AST-A1 | 1:6,000 | APSGAQRLYGFGLa | Vitzthum et al., 46 | Dr. H. Agricola (Jena, Germany) |

| AT2 | 1:5,000 | GFKNVEMMTARGFa | Veenstra and Hagedorn, 42 | Dr. J. Veenstra (Bordeaux, France) |

| SIF3 | 1:1,000 | AYRKPPFNGSIFa | Terhzaz et al., 37 | Dr. J. Veenstra (Bordeaux, France) |

| FMRF4 | 1:2,000 | FMRFa | Marder et al., 15 | Dr. E. Marder (Brandeis Univ., USA) |

| MIP5 | 1:500 | GWQDLQGGWa | Predel et al., 25 | Dr. M. Eckert (Jena, Germany) |

| sNPF6 | 1:1,000 | PQRLRWa | Johard et al., 12 | Dr. J. Veenstra (Bordeaux, France) |

| TKRP7 | 1:1,000 | APSGFLGVRa | Winther and Nässel, 48 | Dr. D.R. Nässel (Stockholm, Sweden) |

All primary antisera were produced in rabbits.

allatostatin-A;

allatotropin;

Ser-Ile-Phe-amide;

Phe-Met-Arg-Phe-amide;

myoinhibitory peptide;

short neuropeptide F;

tachykinin-related peptides.

Description of antiserum production and specificity controls

AST-A antiserum

The AST-A antiserum was raised against synthetic D. punctata allatostatin 7 (APSGAQRLYGFGLamide) coupled to thyroglobulin with glutaraldehyde (Vitzthum et al., 1996). The specificity of the antiserum was characterized by a competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), which showed that the serum crossreacted with other members of the A-type ASTs characterized by a C-terminal Y/FXFGLamide, and preadsorption with antigenic peptide abolished immunolabeling (Vitzthum et al., 1996). This peptide shares the AST-A consensus sequence YXFGLAa with AST-As 1 to 5 of Ae. aegypti (Predel et al., 2010). Specificity was confirmed by the preadsorption of the antiserum with synthetic Dip-AST-7 (Sigma) at concentrations of 10 nM, 100 nM, 1 μM, and 10 μM. Preadsorption with 1 μM and 10 μM synthetic Dip-AST-7 completely abolished the immunostaining.

AT antiserum

The AT antiserum was raised in rabbit against synthetic Mas-AT (GFKNVEMMTARGFamide) coupled to thyroglobulin with glutaraldehyde, and the specificity of the antiserum was tested by competitive ELISA (Veenstra and Hagedorn, 1993). The Mas-AT shares the consensus sequence EMMTARGFa with the AT of Ae. aegypti (Veenstra and Costes, 1999; Predel et al., 2010). Specificity was confirmed by the preadsorption of the antiserum with synthetic Mas-AT (Bachem, Bubendorf, Switzerland) at concentrations of 10 nM, 100 nM, 1 μM, and 10 μM. The preadsorption with 1 μM and 10 μM synthetic Mas-AT completely abolished the immunostaining.

SIFamide antiserum

Immunization with the full SIFamide (AYRKPPFNGSIFamide) coupled to thyroglobulin using difluorodinitrobenzene was used to generate the antiserum to D. melanogaster SIFamide, and standard preadsorption controls were made for immunocytochemistry (Terhzaz et al., 2007). The Ae. aegypti SIFamide shares an almost complete consensus sequence (XYRKPPFNGSIFa) with the D. melanogaster SIFamide (Predel et al., 2010). In Ae. aegypti, specificity was confirmed by the preadsorption of the antiserum with synthetic D. melanogaster SIFamide at concentrations of 10 nM, 100 nM, 1 μM, and 10 μM. Preadsorption with 1 μM and 10 μM synthetic SIFamide completely abolished the immunostaining.

FMRFamide antiserum

The FMRFamide antiserum (No. 671N) was raised in rabbit against synthetic FMRFamide conjugated to thyroglobulin (Marder et al., 1987). Specificity tests by radioimmunoassay showed crossreactivity of the antiserum with various C-terminally extended RFamides (Marder et al., 1987). In Ae. aegypti, specificity was confirmed by the preadsorption of the antiserum with synthetic FMRFamide and FLRFamide (both Sigma) at concentrations of 10 nM, 100 nM, 1 μM, and 10 μM. Preadsorption with 1 μM and 10 μM synthetic FMRFamide and FLRFamide completely abolished the immunostaining.

MIP antiserum

The myoinhibitory peptide (MIP) antiserum was raised in rabbit against the full sequence of synthetic P. americana (Pea-) MIP-1 (GWQDLQGGWamide) coupled to thyroglobulin with glutaraldehyde. Specificity was confirmed by replacing the antiserum with preimmune rabbit serum, as well as by liquid-phase preabsorption using a neuropeptide-conjugate of synthetic Pea-MIP-1 (Predel et al., 2001). The antiserum has been used for the immunolabeling of neurons in D. melanogaster (Santos et al., 2007; Carlsson et al., 2010); MIPs of Ae. aegypti and D. melanogaster share the same consensus sequences (W(X6)Wamide; Nässel and Winther, 2010; Predel et al., 2010). In Ae. aegypti, specificity was confirmed by the preadsorption of the antiserum with synthetic Pea-MIP-1 at concentrations of 10 nM, 100 nM, 1 μM, and 10 μM. Preadsorption with 1 μM and 10 μM synthetic Pea-MIP-1 completely abolished the immunostaining.

sNPF antiserum

The short neuropeptide F (sNPF) antiserum was raised in rabbit against D. melanogaster sNPF-3 (PQRLRWa) coupled with 1,5 difluoro-2,4-dinitrobenzene to BSA (Johard et al., 2008). Specificity was confirmed by replacing the antiserum with preimmune rabbit serum and by liquid-phase preabsorption using synthetic D. melanogaster sNPF-3 (Johard et al., 2008). Drosophila melanogaster sNPF-3 shares the five c-terminal amino acids with Ae. aegypti sNPF-3 (APSQRLRWa; Predel et al., 2010). In Ae. aegypti, specificity was confirmed by the preadsorption of the antiserum with synthetic Ae. aegypti sNPF-3 and Ae. aegypti sNPF-2 (APQLRLRFa; Predel et al., 2010) (both synthesized by Coring System Diagnostix, Gernsheim, Germany) at concentrations of 10 nM, 100 nM, 1 μM, and 10 μM. Preabsorption with 1 μM and 10 μM synthetic sNPF-3 completely abolished the immunostaining, whereas preabsorption with sNPF-2 had no influence on immunocytochemistry at any concentration.

TKRP antiserum

The TKRP antiserum was raised in rabbit against the full peptide sequence of LemTKRP-1 (APSGFLGVRamide) coupled to BSA with carbodiimide (Winther and Nässel, 2001). This antiserum is known to detect TKRPs in other insects by recognizing a distinct consensus sequence, FXGXRamide, also shared by Ae. aegypti (Predel et al., 2010). In Ae. aegypti, specificity was confirmed by the preadsorption of the antiserum with synthetic LemTKRP-1 at concentrations of 10 nM, 100 nM, 1 μM, and 10 μM. Preadsorption with 1 μM and 10 μM synthetic LemTKRP-1 completely abolished the immunostaining.

Neurobiotin application

Anterograde neurobiotin staining of OSNs was performed according to Ignell et al. (2005). Briefly, a glass capillary filled with dH2O was placed over the intact scapus for 2 minutes. The dH2O was then replaced with 4% neurobiotin in 1M KCl saline, and the capillary was put back over the scapus, and the open end sealed with Vaseline. The insect was kept in a humid chamber for 8 hours at 4°C to allow the neurobiotin to diffuse through the antennal nerve. Afterwards, each insect was dissected and all the brains were processed for sNPF immunocytochemistry as described above. Cy3-coupled streptavidin (1:300, Jackson ImmunoResearch), which was used to visualize neurobiotin, was added to the secondary antibody solution.

Microscopy and imaging

Whole-mount specimens were viewed and scanned with an LSM 510 Meta (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) or with a Leica TCS SP2 or SP5 (Leica, Bensheim, Germany) laser-scanning confocal microscope system equipped with Plan-Neofluar 40× (Zeiss), HCX PL APO 40× (Leica), PL APO 63× (Zeiss, Leica) oil immersion objectives or a PL APO 63× glycerol objective (Leica). All fluorescent labels (Alexa 488, Exmax 490 nm, Emmax 508 nm; Cy3, Exmax 550 nm, Emmax 570 nm; Cy5, Exmax 650 nm, Emmax 674 nm) were excited using an argon laser at 488 nm, an He/Ne 1 laser at 543 nm, and an He/Ne laser at 633 nm. Alexa 546 (phalloidin) stainings were excited with an He/Ne 1 laser at 543 nm. Immunostained specimens were scanned at a resolution of 1024 × 1024 pixels with a pinhole size of 1 airy and a distance between optical sections of 1 μm. Final images resulted either from maximal projections of a certain number of optical sections or from single representative sections out of a stack of optical sections. Reconstructions were obtained using modified camera lucida techniques on the projection of a series of high-resolution tagged image files obtained from Z-stack conversion. The final reconstructed image was scanned using an HP Pro scanner (Corvallis, OR) and processed in Adobe Photoshop (San Jose, CA). All image plates were aligned and adjusted for contrast with Adobe Photoshop.

RESULTS

MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry

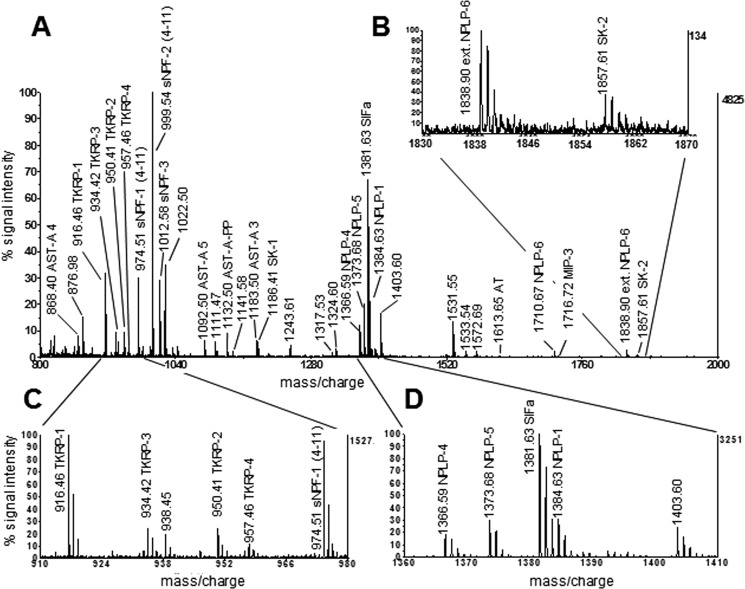

Direct MALDI-TOF mass spectrometric peptide profiling of single ALs revealed numerous ion signals within the mass range from 800–3,000 Da (Fig. 1). The mass spectra of all ALs were nearly identical. In only a few cases did additional signals occur; these signals were likely due to contamination and included ion signals of very low intensity (less than 5% above baseline), which were mass-identical with corazonin and pyrokinins. Within the spectra of both sexes, we found 28 ion signals, all of which were mass-identical with Ae. aegypti neuropeptides, including precursor peptides, recently identified by tandem mass spectrometry (Predel et al., 2010). No sexual dimorphism was observed in the neuropeptidome of male and female ALs (Table2). SIFamide, sNPF-14–11, −2 and −3, neuropeptide-like precursor-1 (NPLP-1) peptides (NPLP-1–4, 1–5, 1–6), and TKRPs (TKRP-1, −2, −3) were highly abundant, and present in nearly all spectra (90–100%; Table2). In addition, mass signals typical of specific AST-A peptides, AT, and sulfakinins (SKs) were detected regularly (20–75% abundance) (Table2). Ion signals matching putative extended FMRFamides 3 and 7, AST-C, and MIP-3 occurred in less than 20% of the samples (Table2). The complete list of peptides, which were identified by mass-match from ALs of Ae. aegypti, is given in Table2.

Figure 1.

A: A representative MALDI-TOF mass spectrum obtained after direct profiling a single female Ae. aegypti AL. Insets B–D: Magnified views of A. Left y-axis: relative signal intensity after autoscaling to maximum peak intensity in the selected mass range; right y-axis: peak intensity in absolute counts.

Table 2.

Calculated and Measured Mono-Isotopic Masses [M+H]+

| mean | abundance [%] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptides | sequence | calculated | measured | mean deviation | male (n=20) | female (n=20) |

| A-type allatostatins | ||||||

| AST-A 4 | RVYDFGLa | 868,4676 | 868,4621 | 0,0444 | 45 | 40 |

| AST-A 5 | LPNRYNFGLa | 1092,5949 | 1092,6023 | 0,0589 | 70 | 75 |

| AST-A 3 | ASAYRYHFGLa | 1183,6007 | 1183,6038 | 0,0565 | 70 | 70 |

| AST-A-PP | RYIIEDVPGA-OH | 1132,5997 | 1132,5747 | 0,0669 | 15 | 20 |

| C-type allatostatins | ||||||

| AST-C | QIRYRQCYFNPISCF-OH | 1935,9154 | 1935,9050 | 0,1660 | 10 | 5 |

| AST-C | pQIRYRQCYFNPISCF-OH | 1918,9100 | 1918,9164 | 5 | 0 | |

| Allatotropin | ||||||

| AT | APFRNSEMMTARGFa | 1613,7675 | 1613,7534 | 0,0749 | 70 | 55 |

| Slfamide | ||||||

| SIFamide | GYRKPPFNGSIFa | 1381,7375 | 1381,7448 | 0,0657 | 100 | 100 |

| FMRFamides | ||||||

| FMRFa-3 | AGQGFMRFa | 912,4514 | 912,4546 | 0,0393 | 20 | 10 |

| FMRFa-7 | GSGNLMRFa | 880,4463 | 880,4472 | 0,0414 | 15 | 5 |

| Myoinhibitory peptides | ||||||

| Mip 3 | VNAGPAQWNKFRGSWa | 1716,8723 | 1716,8640 | 0,0900 | 15 | 10 |

| short neuropeptide F | ||||||

| sNPF-1 (4–11) | SPSLRLRFa | 974,5894 | 974,5958 | 0,0457 | 100 | 100 |

| sNPF-2 (4–11) (x2) | APQLRLRFa | 999,6210 | 999,6275 | 0,0472 | 100 | 100 |

| sNPF-3 | APSQRLRWa | 1012,5805 | 1012,5877 | 0,0473 | 100 | 100 |

| sNPF-1 | AVRSPSLRLRFa | 1300,7966 | 1300,8048 | 0,0722 | 15 | 20 |

| Neuropeptide-like precursor 1 | ||||||

| NPLP-4 | NLASARASGYMLNa | 1366,6901 | 1366,6994 | 0,0659 | 100 | 100 |

| NPLP-5 | NIASLARKYELPa | 1373,7905 | 1373,7980 | 0,0660 | 100 | 100 |

| NPLP-1 | SYRSLLRDGATFa | 1384,7337 | 1384,7599 | 0,0663 | 60 | 65 |

| NPLP-6 | NIQSLLRTGMLPSIAP-OH | 1710,9576 | 1710,8202 | 0,0777 | 90 | 95 |

| ext. NPLP-6 | NIQSLLRTGMLPSIAPK-OH | 1839,0521 | 1839,0482 | 0,0732 | 95 | 85 |

| NPLP-2 | NLGSLARAGLLRTPSTDYL-OH | 2018,1034 | 2018,0983 | 0,0625 | 75 | 65 |

| NPLP-7 | NMQSLARDNSLPHFAGAAAQES-OH | 2315,0838 | 2315,1143 | 0,0787 | 70 | 55 |

| sulfakinin | ||||||

| SK-1 | FDDYGHMRFa | 1186,5104 | 1186,5011 | 0,0628 | 25 | 45 |

| SK-2 | GGGGEGEQFDDYGHMRFa | 1857,7615 | 1857,7446 | 0,0792 | 25 | 20 |

| Tachykinin related peptides | ||||||

| TKRP-1 (x2) | APSGFLGLRa | 916,5363 | 916,5423 | 0,0435 | 100 | 100 |

| TKRP-3 | APSGFLGMRa | 934,4927 | 934,4969 | 0,0437 | 95 | 90 |

| TKRP-2 | VPSGFTGMRa | 950,4876 | 950,4980 | 0,0429 | 95 | 95 |

| TKRP-4 | VPNGFLGVRa | 957,5629 | 957,5361 | 0,0598 | 60 | 60 |

Putative Ae. aegypti neuropeptides detected by the direct profiling of single ALs, and matching with masses calculated from sequences of 28 predicted peptides stemming from 10 different neuropeptide genes in Ae. aegypti. Masses, which we obtained at most once per sex, were not included in further analysis (1770.8149 (sNPF-PP 4), 2229.9816 (sNPF-PP 2), 2599.2682 (NPLP-1–8)). x2: two copies on respective precursor (Predel et al., 2010).

Immunolabeling

To verify the neuronal localization of the peptide precursor products indicated by mass spectrometry, we applied antisera recognizing mature products of at least seven neuropeptide genes (Table1). For each neuropeptide, at least five insects of each sex were analyzed. No obvious sexual dimorphism was observed in immunolabeling. Immunolabeling against NPLP-1 peptides, AST-C, and SK was not performed because appropriate antisera were not available.

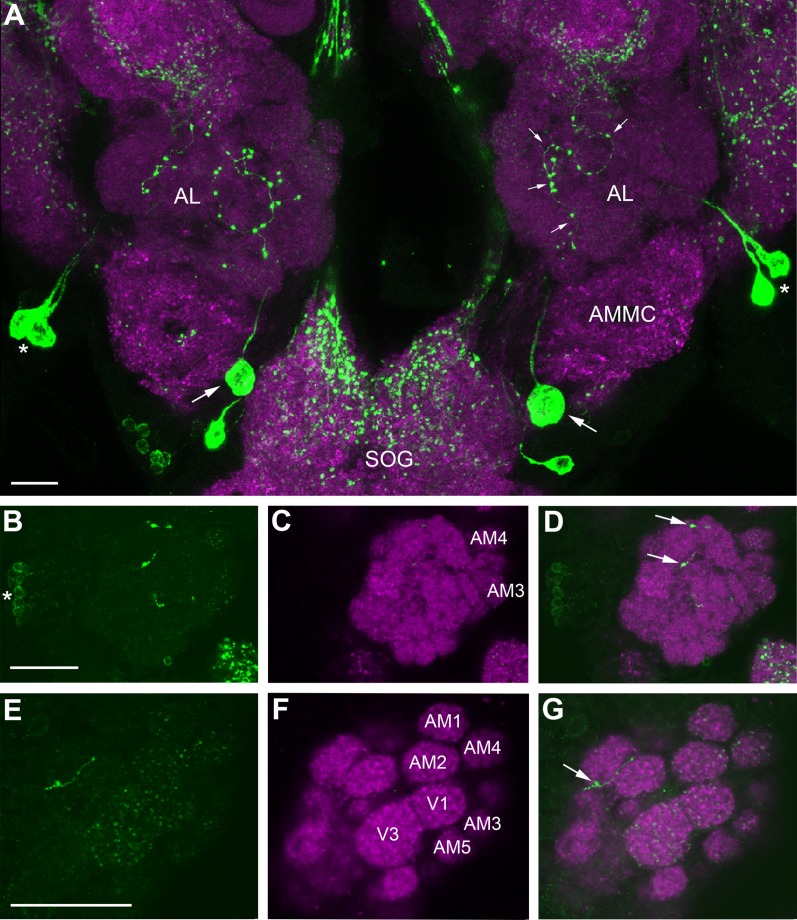

AST-A expression in local interneurons and extrinsic neurons

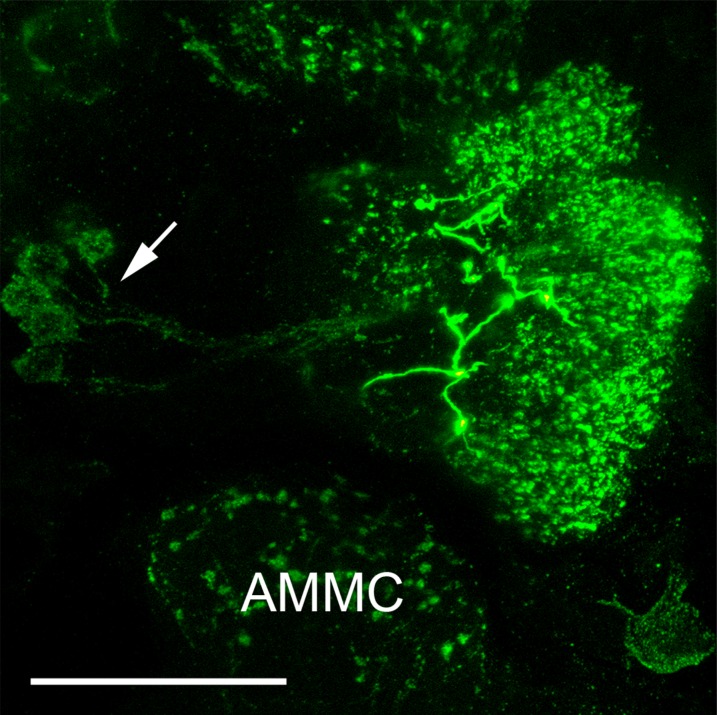

Immunolabeling with AST-A antiserum was observed in 12–16 local interneurons (LNs), with cell bodies located lateral to the AL (Fig. 2B). The LNs innervated the ventral (V1 and V3; nomenclature according to Ignell et al., 2005) and anteromedial glomeruli (AM1–AM5) with thin branches, whereas other glomeruli appeared to receive little or no innervation (Fig. 2B–G). Moreover, we observed an extrinsic neuron innervating each AL. The cell bodies of these neurons were located ipsilaterally in the anterior part of the subesophageal ganglion (SOG) (Fig. 2A, arrow). These neurons innervated the ALs with sparse arborization of fibers with large varicosities (Fig. 2) restricted to the Johnston’s organ center (Fig. 2A), and the mediodorsal glomeruli innervated by maxillary palp OSNs (data not shown). We observed a process of this neuron extending outside the AL but were not able to trace the projection of it.

Figure 2.

Confocal images of a female Ae. aegypti AL labeled with antisera against AST-A (green) and synapsin (magenta). All frontal views. A: Maximum projection of 27 optical sections showing the middle to posterior portion of the ALs and the anterior part of the subesophageal ganglion (SOG). Two large cell bodies (arrow) in the SOG send their neurites into the ipsilateral AL, which give rise to thick fibers and varicosities (small arrows) in the center neuropil of the AL. From there, a sparse fiber network invests the glomerular neuropil. Note that the thick fibers never enter the glomeruli but stay outside between them (see also D,G). The neurites extending from the cell bodies indicated by asterisks bypass the ALs. B–D: Maximum projections of two optical sections in the anterior portion of the AL. A group of 12 to 16 cell bodies in the lateral cell group (asterisk) project their neurites into the AL neuropil. The ventral and anteromedial glomeruli show innervations with immunopositive fibers, whereas other glomeruli show little or no immunostaining. Arrows label thick AST-A-immunoreactive varicosities stemming from the posterior meshwork. E–G: A single optical section through the anterior part of the AL shows the ventral and anteromedial glomeruli with AST-A immunostaining. The arrow marks a thick fiber running between two glomeruli. AMMC: antennal motor and mechanosensory center. Scale bars = 20 μm.

AT expression in local interneurons

Allatotropin immunolabeling was observed in 4–6 LNs with cell bodies lateral to the AL (Fig. 3). The LNs arborized in all or most glomeruli without apparent glomerular preference (Fig. 3). We did not observe any AT-immunoreactive processes outside the AL, excluding the fact that these neurons are extrinsic.

Figure 3.

Maximum projection of 35 optical sections showing a female Ae. aegypti AL labeled with an antiserum against Mas-AT. Four to six large cell bodies are found in the lateral cell cluster of the AL (arrowhead). The Mas-AT-immunoreactive LNs provide a dense varicose innervation of most if not all glomeruli. Scale bar = 25 μm.

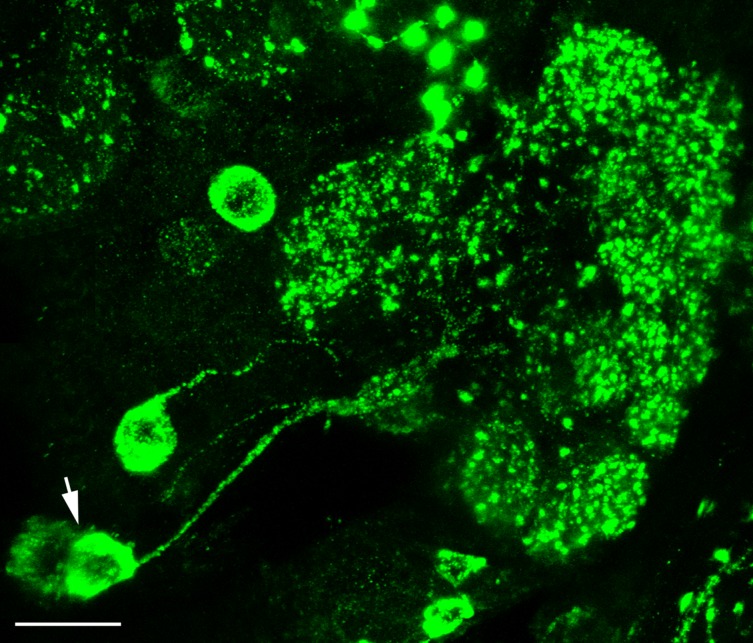

SIFamide expression in extrinsic neurons

The SIFamide antiserum labeled a dense meshwork of varicose fibers in the AL that innervated all or most glomeruli without apparent glomerular preference (Fig. 4). Four SIF-immunoreactive cell bodies were found in the pars intercerebralis, with processes in the medial bundle that innervated most brain neuropils (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Immunolabeling with anti-SIFamide in the AL of Ae. aegypti. Maximum projection of 25 optical sections showing SIFamide immunoreactivity (green) and synapsin (magenta) in the ALs of females (A–C) and males (D–F). Scale bars = 25 μm.

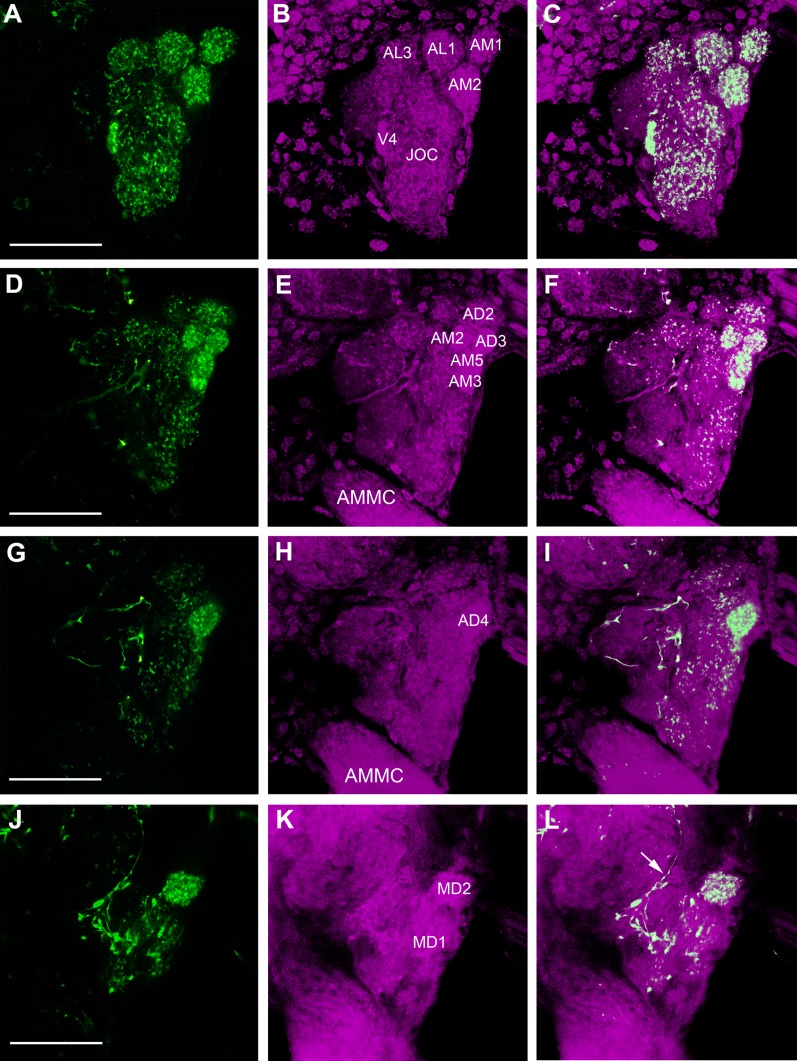

FaRP expression in AL neurons

The FMRFamide antiserum used in this study recognizes various FaRPs, including the extended FMRFamides, MS, sNPFs, and SKs that were identified by mass spectrometry of male and female ALs.

FMRFamide immunoreactivity was observed in 15–20 LNs with cell bodies located lateral to the AL (Figs. 5, 7E). These neurons supplied innervation to all glomeruli and the Johnston’s organ center of the AL (Figs. 5, 6), and did not give rise to any apparent processes outside the AL. We observed a dense innervation of the anteromedial (AM1–5), anterodorsal (AD2–4), and anterolateral (AL1) glomeruli, as well as of a ventral glomerulus (V4) (Fig. 6). Moreover, FMRFamide immunoreactivity was observed in a pair of extrinsic neurons, one in each hemisphere, which innervated the ALs and had widefield innervation in distinct neuropil areas of the protocerebrum (Fig. 7). These neurons innervated the ALs sparsely with thick processes with large varicosities (Fig. 7A,B). Innervation by these processes was restricted to the posterior and lateral portions of the AL and was extraglomerular (Fig. 7A,B). Varicose fibers, however, wrapped around the maxillary-palp-associated glomerulus, MD1 (Fig. 7A; Ignell et al., 2005). The axons of these neurons exited the ALs anterolaterally and then projected medially through the lateral accessory lobe (LAL) to the level of the central complex (CC) (Fig. 7B–E). At this level, the axon of each neuron bifurcated, and one branch projected anteriorly, parallel with the inner antennocerebral tract (IACT) (Fig. 7D,E). This axonal branch displayed further branching shortly after the bifurcation, and each of these branches projected into the superior protocerebrum (Fig. 7D,E); we were unable to trace the full extension of these branches in the protocerebrum. The second branch extended medially, sending a bundle of fibers into the fan-shaped body of the CC (Fig. 7D,E), invading it by densely packed arborizations. Parallel to the axon exiting from the AL, we observed a single varicose fiber that innervated both the LAL and the ventral body of the CC (Fig. 7E).

Figure 5.

FMRFamide immunoreactivity in the AL of a female Ae. aegypti. Maximum projection of 37 optical sections showing a frontal image of an AL, where FMRFamide immunoreactivity is observed in all AL glomeruli. In addition, thick varicose FMRFamide-immunoreactive fibers of an extrinsic neuron are visible at the center of the AL neuropil. The arrow indicates the FMRFamide-immunoreactive cell bodies in the lateral cell cluster. AMMC: antennal motor and mechanosensory center. Scale bar = 25 μm.

Figure 7.

A: Reconstruction of the FMRFamide-immunoreactive extrinsic neuron wrapping around the MD1 glomerulus at the dorsomedial portion of the AL. B: Maximum projection of 40 optical sections showing a frontal view of the FMRFamide-immunoreactive extrinsic neuron in the posterolateral region of the AL of a female Ae. aegypti. Note the loop-like thick varicose FMRFamide-immunoreactive fibers (arrow). C: Maximum projection of 40 optical sections showing the axon of the FMRFamide-immunoreactive extrinsic neuron, which bifurcates at the level of the central complex (CC) and extends one branch, which further bifurcates, into the superior protocerebrum (arrow), and a second branch into the base of the CC (arrow head). D: Maximum projection of 40 optical sections showing a bifurcated branch of the axon that extends into the superior protocerebrum where it further branches (arrow) (see also E). E: Frontal reconstruction of the FMRFamide-immunoreactive neurons in the brain of Ae. aegypti. Fifteen to 20 cell bodies of LN in the lateral cell cluster project primary neurites into the AL as one thick bundle that supplies immunoreactivity to the AL glomeruli. Intensely stained and clearly delineated medial glomeruli can be seen in the AL neuropil. A pair of FMRFamide-immunoreactive extrinsic neurons connects the AL neuropil with higher brain centers. Axons of these neurons exit the AL and run medially through the lateral accessory lobe (LAL) and bifurcate at the level of the CC. Here, one branch ascends further into the superior protocerebrum and a second branch extends medially to the base of the CC and arborizes densely in the core of the CC. A varicose fiber innervating the LAL and the ventral body of the CC is also seen (arrow). AMMC: antennal motor and mechanosensory center; OE: esophagus; AN: antennal nerve; SOG: subesophageal ganglion; OL: optic lobe. Scale bars = 25 μm.

Figure 6.

Detailed innervation pattern of FMRFamide-immunoreactive fibers (green) in the AL neuropil (magenta) of a female Ae. aegypti. A–C: Maximum projection of six optical sections showing a frontal image of the AL, where strong FMRFamide-immunoreactivity is observed in the anteromedial (AM1, AM2) and anterolateral glomeruli (AL1, AL3), as well as in a ventral glomerulus (V4). Note the compartmentalization of immunoreactivity in the AL glomeruli and the Johnston’s organ center (JOC). D–I: Maximum projections of six optical sections showing the strong immunoreactivity in the anteromedial (AM2, AM3, AM5) and anterodorsal glomeruli (AD3, AD4). Note that the lateral part of the AL is almost devoid of immunoreactivity. Coarse varicose fibers are also seen in this posterolateral region of the AL. J–L: Maximum projection of five optical sections showing the axon (arrow) of the FMRFamide-immunoreactive extrinsic neuron that connects the protocerebrum and the AL. The varicose fibers of this neuron converge on the posterior and lateral side of the AL. At this level the varicose neuron starts to wrap around the maxillary palp glomerulus, MD1, sparing neighboring glomeruli like MD2. AMMC: antennal motor and mechanosensory center. Scale bars = 25 μm.

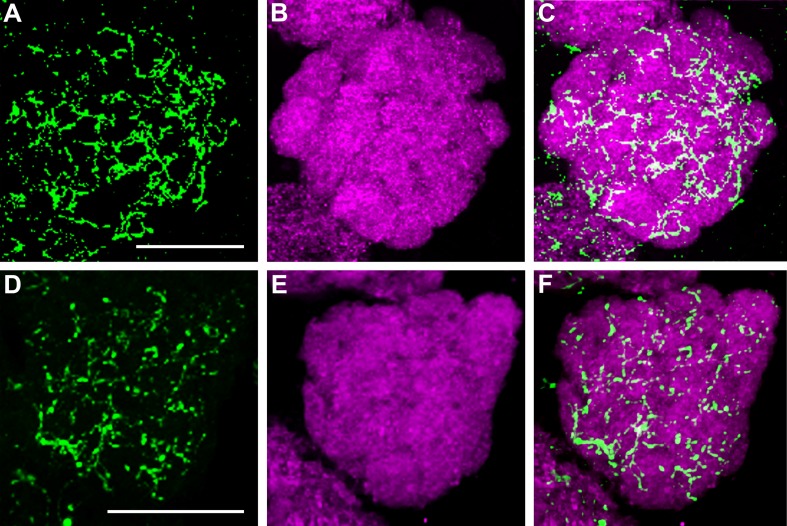

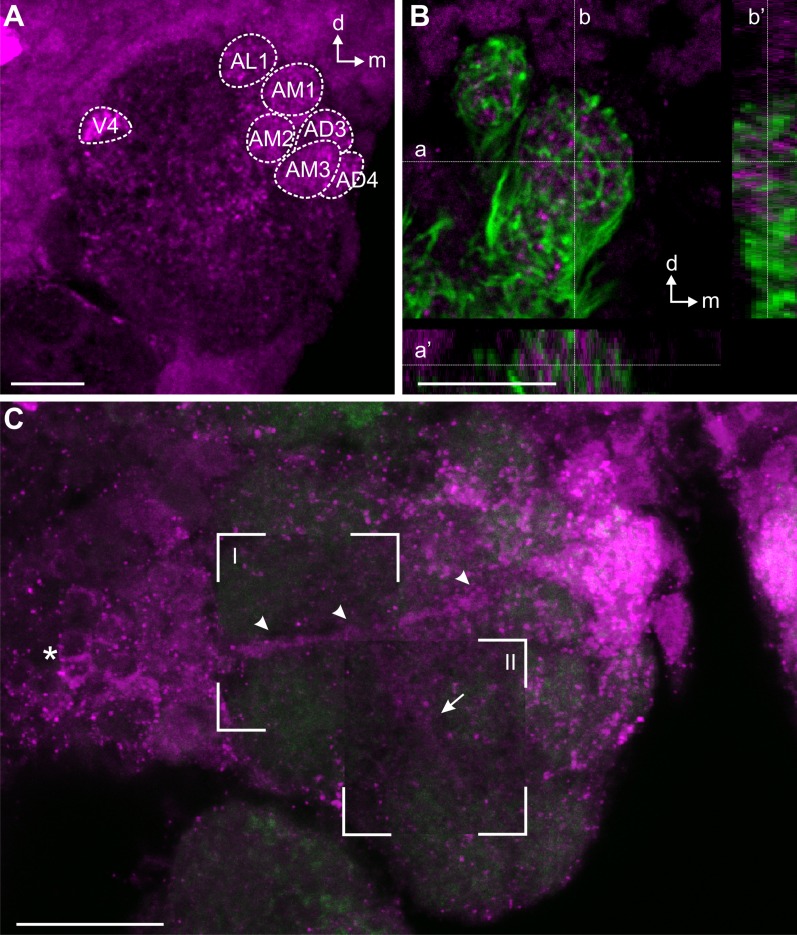

sNPF is differentially distributed in olfactory glomeruli

Strong sNPF immunoreactivity was observed in the anteromedial (AM1–5) and anterodorsal (AD2–4) glomeruli, as well as in an anterolateral (AL1) and a ventral (V4) glomerulus of the AL (Fig. 8A). Remaining glomeruli showed only sparse varicose sNPF immunoreactivity (Fig. 8A, C). The sNPF immunoreactivity did not overlap with the anterograde staining of the OSNs (Fig. 8B), excluding that the OSNs are the source for the sNPF (Fig. 8B). Instead, we identified four strongly labeled cell bodies located lateral to the AL. These cells can be accounted as LNs as they projected their primary neurites as a tract into the AL and supplied uniform varicose innervation to the glomeruli (Fig. 8C). In some preparations, the four strongly labeled cell bodies were accompanied by up to six additional weakly labeled somata, suggesting up to 10 sNPF-containing LNs. We did not observe any immunoreactive fibers exiting the AL, excluding that the sNPF neurons are extrinsic.

Figure 8.

sNPF immunoreactivity (magenta) in the AL of a female Ae. aegypti. A: Maximum projection of 38 optical sections, showing six strongly labeled glomeruli in the anterior part of the AL (AL1, AM1–3, AD3, AD4) and one strongly labeled glomerulus in the ventral area of the AL (V4). B: Comparison of sNPF immunostaining (magenta) with back-filled OSN fibers (green) revealed no overlap between sNPF and OSN profiles. Confocal image stack of 13 optical images. Insets below and to the right show the z-stack along lines a and b, whereas lines a′ and b′ mark the position of the main optical image within the stack. C: Collage of maximum projections containing different numbers of optical sections from the same stack of 16 optical sections, revealing a cell cluster lateral to the AL sending axons to the AL (arrowheads) innervating the glomeruli. The background maximum projection contains sections 1 to 7, and maximum projections shown in I and II contain optical sections 7 to 16 and 11 to 13, respectively. Green, synapsin immunostaining; compare with FMRFamide immunostaining in Figs. 5, 6. A–C: Z-distances between optical sections: 0.5 μm. Scale bars = 10 μm.

MIP expression in local interneurons

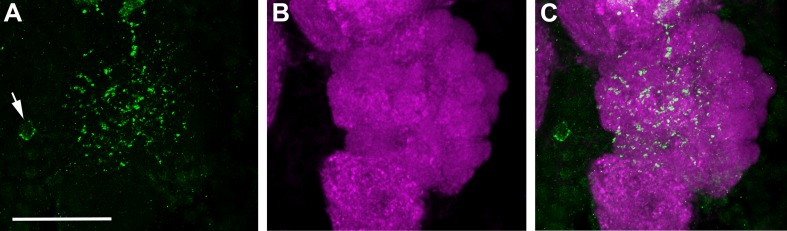

MIP immunoreactivity was observed in two LNs with cell bodies located lateral to the AL (Fig. 9). These LNs sparsely arborized in most if not all glomeruli, with no particular glomerular preference. No axonal processes were observed, excluding that the MIP neurons are extrinsic.

Figure 9.

Anti-MIP immunoreactivity in the AL of a female Ae. aegypti. Maximum projection of 25 optical sections showing labeling with anti-MIP (green) and synapsin (magenta). Scale bar = 25 μm.

TKRP expression in local interneurons

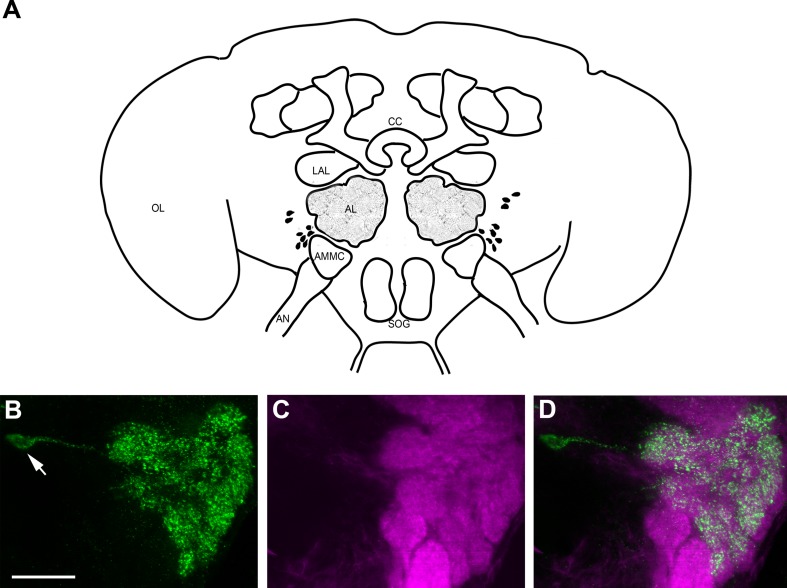

TKRP immunolabeling was derived from seven to nine LNs with cell bodies lateral to the AL (Fig. 0). The TKRP-immunoreactive neurons arborized in most if not all glomeruli, without any glomerular preference, as well as in the Johnston’s organ center of the AL. We did not observe any processes extending outside the AL. TKRP immunoreactivity was not observed in the peripheral olfactory system.

Lem-TKRP immunolabeling in the AL of Ae. aegypti. A: Schematic representation of a mosquito brain showing the distribution of TKRP-immunoreactive cell bodies supplying the AL of Ae. aegypti. (B–D) Maximum projections of 15 optical sections showing labeling with TKRP (green) and synapsin (magenta) in the AL of a female mosquito. A uniform granular appearance of TKRP immunoreactivity was found in the AL neuropil. The arrows point to the TKRP-immunoreactive cell bodies. AMMC: antennal motor and mechanosensory center; CC: central complex; LAL: lateral accessory lobe. Scale bars = 25 μm.

DISCUSSION

A prerequisite to understanding the function of neuropeptides in a given neuronal network, like the AL, is knowledge of the neuropeptides involved and their cellular localization. The direct tissue profiling protocol used in this study allowed for the fast and reliable detection of the neuropeptides from Ae. aegypti ALs. Between the numerous mass spectra, minor discrepancies in terms of ion signal intensity were detected. The analysis of the 40 mass spectra revealed, by mass-match, 28 mature peptides that are products of 10 neuropeptide genes. This represents 40% of the peptides from Ae. aegypti that were structurally identified in its central nervous system (Predel et al., 2010). Most of the neuropeptides were recognized by one of the seven neuropeptide antisera used in this study. Each of the neuropeptides found in the olfactory system is discussed separately below. The results suggest a rich substrate for modulation and plasticity within the olfactory system of Ae. aegypti.

AST-A expression in LNs and extrinsic neurons

In Ae. aegypti, the AST-A gene encodes for five ASTs expressed in the central nervous system and the midgut (Veenstra et al., 1997; Hernández-Martinez et al., 2005; Predel et al., 2010). Three of these neuropeptides, as well as a structurally unrelated AST-A precursor peptide (PP-1), were detected in the AL.

Allatostatin-A-immunoreactive LNs have been described in many species with innervation patterns similar to the pattern observed in Ae. aegypti (Homberg and Müller, 1999; Schachtner et al., 2005; Carlsson et al., 2010; Neupert et al., 2012). This distribution suggests that AST-A may function as a local neuromodulator in the AL. Alternatively, or in addition, AST-A LNs may be involved in the formation of the AL network during development, as has been suggested for M. sexta (Utz et al., 2007).

Extrinsic AST-A neurons have been found in evolutionarily distant species, including P. americana (Schildberger and Agricola, 1992; Neupert et al., 2012), M. sexta (Utz and Schachtner, 2005), and D. melanogaster (Carlsson et al., 2010); only in M. sexta has the source of the AST-A extrinsic input been identified. The identification of an extrinsic AST-A neuron in Ae. aegypti supports the hypothesis that AST-A extrinsic neurons are a plesiomorphic characteristics of the AL (Schachtner et al., 2005). The functional significance of these types of neurons is unknown.

Expression of AT in LNs

The at-gene in Ae. aegypti encodes a single copy of the neuropeptide (Veenstra and Costes, 1999), which is expressed in the central nervous system and midgut (Hernández-Martinez et al., 2005; Predel et al., 2010).

In insects in which the distribution of AT has been investigated, antibody staining has been observed in LNs of the AL, and in a few cases in extrinsic neurons (reviewed by Schachtner et al., 2005; see also Berg et al., 2007; Utz et al., 2008; Neupert et al., 2012). In Ae. aegypti, LNs also express AT, which suggests that AT plays a common role in the insect AL. Like AST-As, AT is a candidate molecule involved in AL development (Utz et al., 2007).

SIFamide is expressed in extrinsic neurons

Both the SIFamide sequence and the SIFamide-immunoreactive distribution pattern are highly conserved across insect species (Verleyen et al., ,; Heuer et al., 2012). In Ae. aegypti, Predel et al. (2010) showed by mass spectrometry that SIFamide is expressed in neurosecretory cell clusters of the pars intercerebralis, with fibers throughout the central nervous system of Ae. aegypti. Our study confirmed SIFamide immunolocalization in Ae. aegypti and revealed four immunoreactive cell bodies in the pars intercerebralis, and axons that projected through the medial bundle and gave rise to a large number of varicose processes. These neurons are morphologically homologous to those described in D. melanogaster (Carlsson et al., 2010). SIFamide affects courtship behavior in D. melanogaster (Terhzaz et al., 2007) and is thought to regulate the neural circuits affecting olfactory responsiveness to sexual signals (Carlsson et al., 2010).

FaRPs are expressed in LNs and extrinsic neurons

FMRFamide-related peptides, identified in Ae. aegypti by mass spectrometry, make up the extended FMRFamides, myosuppressin, sNPF, and SKs (Predel et al., 2010). Besides myosuppressin, our mass spectrometric analyses indicate the presence of all of these peptides in the ALs of both male and female Ae. aegypti. The presence of the extended FMRFamides, however, is ambiguous, since these peptides were observed in only a few mass spectra with very low ion intensity.

The FMRFamide antiserum used in this study recognizes most peptides of the FaRP superfamily. The staining pattern we revealed reflects the peptide of all four genes of this superfamily. Previous studies have detected FMRFamide immunoreactivity in the ALs of all insect species studied that originate from LNs (Schachtner et al., 2005; Neupert et al., 2012). By comparing FMRFamide and sNPF immunostaining, we have shown that at least some LNs express sNPF (see below). The observed selective innervation of FaRP-immunoreactive LNs in specific AL glomeruli of Ae. aegypti is compelling. The functional identity of a subset of these glomeruli has been shown by anterograde staining of functionally characterized OSNs from antennal trichoid sensilla (Ghaninia et al., 2007); glomeruli AM2, AM4, AD2, and AD3 all receive innervation from OSNs that respond to mosquito oviposition attractants (Ghaninia et al., 2007). Hence, FaRPs may play a role in regulating oviposition-related behaviors.

FMRFamide-immunoreactive extrinsic neurons are another feature described in other insect species (reviewed by Schachtner et al., 2005). The observed morphology of the FMRFamide-immunoreactive extrinsic neuron in Ae. aegypti is, however, a unique finding. The extrinsic neuron connecting a maxillary palp-associated glomerulus, MD1 (Ignell et al., 2005), to areas that are involved in motor regulation, the CC and LAL, suggests a unique FaRP signaling pathway mediating odor perception and motor control in these mosquitoes. Although the functional role of these extrinsic neurons is unknown, their widefield arborization in areas of the protocerebrum and the AL suggests that they may regulate key physiological functions involved in odor-mediated behavior.

sNPF is expressed in LNs

The sNPF antiserum used in this study specifically recognizes c-terminal RLRWamide but not RLRFamide. Of the Ae. aegypti sNPFs, only sNPF-3 ends with RLRWamide, whereas the other sNPF peptides end with RLRFamide (Table2). Using sNPF-3, in combination with the FMRFamide antiserum, which selectively recognizes RFamides, we were thus able to distinguish the sNPF substaining from the rest of the FMRFamide staining. The rest of the FMRFamide staining recognizes peptides of all four peptide families belonging to the superfamily of FaRPs.

The sNPF immunostaining revealed a set of LNs that innervated all glomeruli, but a number of anterior glomeruli and one ventral glomerulus were more intensely stained. A similar staining pattern was observed for the FMRFamide immunostaining, suggesting that the immunolabeling of the extrinsic neuron with the FMRFamide antibody is due to the expression of extended FMRFs, sulfakinins, or myosuppressin. We cannot exclude the fact that the described neurons express peptides belonging to more than one of the FaRP peptide families. As discussed above, FMRFamide-immunoreactive LNs and extrinsic neurons seem to be a common feature of the AL innervation pattern across many insect species (Schachtner et al., 2005). We postulate that in other insect species as well, sNPF very likely is responsible for LN staining, whereas other peptides of the FaRP superfamily are expressed by the extrinsic neurons.

Results from staining with the same sNPF antiserum in D. melanogaster contrast the results in this study. In D. melanogaster, sNPF is expressed in a subset of OSNs from the antennae and maxillary palps that innervate a subset of 13 glomeruli distributed across the AL (Nässel et al., 2008; Carlsson et al., 2010). In comparison to the situation in other insect species, the situation in Ae. aegypti may in an evolutionary sense reflect the more typical insect situation, whereas the sNPF expression in D. melanogaster may have been derived later. However, the localization of sNPF expressing neurons has so far only been described in D. melanogaster and Ae. aegypti, and more data from different insect species have to be provided to better support this hypothesis. An interesting question for future studies is to examine whether these glomeruli are involved in the processing of similar odors in both species.

MIPs are expressed in LNs

Five MIPs are processed in the central nervous systems and midguts of Ae. aegypti, based on mass spectrometric analysis (Predel et al., 2010). The detection of only a single MIP (MIP-3) in the current study can be explained by the presence of Arg in this peptide; the other MIPs are devoid of Arg or other basic amino acids and therefore yielded much lower ion intensities (see Predel, 2001).

Studies of MIPs expression in ALs have been conducted in D. melanogaster (Carlsson et al., 2010), M. sexta (Utz et al., 2007), and P. americana (Neupert et al., 2012), and show more MIP-immunolabeled LNs than are found in Ae. aegypti. MIP function in the AL, as well as in the rest of the central nervous system, requires further exploration.

TKRP expression in LNs

The first insect TKRPs were identified in Locusta migratoria (Schoofs et al., 1990), and these neuropeptides share the consensus sequence, FXGXRamide, with TKRPs identified in Ae. aegypti (Predel et al., 2010), and the mosquitoes Anopheles gambiae (Riehle et al., 2002) and Cu. salinarius (Meola et al., 1998). Four of the five isoforms of TKRPs identified in Ae. aegypti (Predel et al., 2010) were identified in AL preparations.

TKRP-expressing LNs seem to be another plesiomorphic feature of the insect olfactory system (reviewed by Schachtner et al., 2005). In D. melanogaster, TKRPs have been shown to have a functional role in olfactory processing, where TKRP-expressing LNs act by presynaptically inhibiting OSNs and ensuing olfactory behavior (Ignell et al., 2009). These neurons also act postsynaptically on other LNs, and interference with TKRP receptor expression in these neurons causes a different behavioral phenotype than that observed in presynaptic interference (Winther and Ignell, 2010). Together, these results suggest that TKRP signaling pathway is involved in sharpening the behavioral response to odors by modulating output from OSNs and LNs.

AST-C expression in ALs

The identification of equimolar amounts of N-terminally blocked (pGlu) and nonblocked forms of AST-C in a number of AL preparations indicates that this neuropeptide might also be involved in olfactory information processing. As is the case with different FaRPs (MS, SKs, FMRFamides), ion signal intensity of AST-C was generally low in AL preparations. Specific antisera were not available and therefore the presence of these peptides in LNs or glomeruli has still to be confirmed. For P. americana, AST-C expression in LNs was experimentally verified by single cell analysis (Neupert et al., 2012).

MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry and neuropeptide detection

Generally, ion signal intensity is only one indicator for the amount of a neuropeptide in a given sample. The quality of a preparation, the intensity of the laser beam, and particularly the amino acid composition of a peptide have a strong impact on the relative abundance of the different ions (see Krause et al., 1999; Predel, 2001; Schachtner et al., 2010). In addition, physiological conditions could influence the amount of peptide in individual animals and thus influence the detection frequency. To minimize this possibility, we worked with animals that were in similar physiological conditions: 2–7-day-old adults fed only sugar water. Finally, very low detection frequencies can also pertain to contaminations from neighboring nontarget tissue. Our mass spectra, which yielded very similar results in terms of the ratios of the different ion signals, are averages resulting from 750–1,000 laser shots, all of which were randomly taken under the condition of constant laser power. The reliability of the relative ion intensities in mass spectra of AL is corroborated by the fact that TKRP-1 and sNPF-2 were always more abundant than the remaining TKRPs/sNPFs; the respective precursors contain two copies of these neuropeptides (Predel et al., 2010). Similar observations concerning the copy number of neuropeptides and their relationship to the intensity of the corresponding ion signals have been made for extended FMRFamides in D. melanogaster (Predel et al., 2004) and also for TKRPs in AL spectra of D. melanogaster and Tribolium castaneum (Schachtner et al., 2010).

We were unable to detect Aedes Head peptides that share limited similarity to sNPFs (Brown et al., 1994) in the mass spectra of the AL. Similarly, Head peptides have not been detected by mass spectrometry in any other part of the central nervous system and midgut of Ae. aegypti (Predel et al., 2010), although synthetic Head peptides are easily detectable by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. A recent study suggested that Head peptides, despite its designation, are expressed in male accessory glands of Ae. aegypti and transferred to the female reproductive tract during copulation (Naccarati et al., 2012).

In summary, our study presents the first detailed analysis of neuropeptides in the AL of a mosquito. Direct tissue profiling using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry revealed 28 mature peptides in Ae. aegypti ALs, which represent the AL neuropeptidome in the mass range from 800–3,000 Da. Immunostainings with seven antisera, which according to the mass spectrometric findings recognized products of seven out of nine neuropeptide genes detected by mass-match in the AL, revealed a varying pattern of glomerular innervation stemming from LNs and from extrinsic neurons.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ROLE OF AUTHORS

All authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: KPS, BS, JS, RI. Acquisition of data: KPS, AR, HS, RI. Analysis and interpretation of data: KPS, AR, SN, RP, JS, RI. Drafting of the article: KPS, JS, RI. Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: SN, RP, BSH, JS, RI. Obtained funding: BSH, RI. Study supervision: JS, RI.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Hans Agricola and Manfred Eckert (both University of Jena, Germany), Erich Buchner (University of Würzburg, Germany), Dick Nässel (Stockholm University, Sweden), and Jan Veenstra (University of Bordeaux, Talence, France) for kindly providing the various antisera. We thank Sharon Rose Hill (Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Alnarp, Sweden) for helpful comments throughout the course of this project. We also thank Lotte Søgaard-Andersen and Jörg Kahnt (both Max Planck Institute of Terrestrial Microbiology, Marburg, Germany) for the use of the mass spectrometer, and Martina Kern (Philipps-University Marburg, Germany) for expert technical assistance. Emily Wheeler is acknowledged for editorial assistance.

LITERATURE CITED

- Berg BG, Schachtner J, Utz S, Homberg U. Distribution of neuropeptides in the primary olfactory center of the heliothine month Heliothis virescens. Cell Tissue Res. 2007;327:385–398. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0318-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MR, Klowden MJ, Crim JW, Young L, Shrouder LA, Lea AO. Endogenous regulation of mosquito host-seeking behavior by a neuropeptide. J Insect Phys. 1994;40:399–406. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson MA, Diesner MA, Schachtner J, Nässel DR. Multiple neuropeptides in the Drosophila antennal lobe suggest complex modulatory circuits. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:3359–3380. doi: 10.1002/cne.22405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements AN. Sensory reception and behaviour. Vol. 2. Wallingford, UK: CABI Publishing; 1999. The biology of mosquitoes. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaninia M, Ignell R, Hansson BS. Functional classification and central nervous projections of olfactory receptor neurons housed in antennal trichoid sensilla of female yellow fever mosquitoes, Aedes aegypti. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:1611–1623. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05786.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant AJ, O'Connell RJ. Age-related changes in female mosquito carbon dioxide detection. J Med Entomol. 2007;44:617–623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Martínez S, Li Y, Lanz-Mendoza H, Rodríguez MH, Noriega FG. Immunostaining for allatotropin and allatostatin-A and -C in the mosquitoes Aedes aegypti and Anopheles albimanus. Cell Tissue Res. 2005;321:105–113. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-1133-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuer CM, Kollmann M, Binzer M, Schachtner J. Neuropeptides in insect mushroom bodies. Arthropod Struct Dev. 2012;41:199–226. doi: 10.1016/j.asd.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homberg U, Müller U. Neuroactive substances in the antennal lobe. In: Hansson BS, editor. Insect olfaction. Berlin, Heidelberg. New York: Springer; 1999. pp. 181–206. [Google Scholar]

- Ignell R, Dekker T, Ghaninia M, Hansson BS. Neuronal architecture of the mosquito deutocerebrum. J Comp Neurol. 2005;493:207–240. doi: 10.1002/cne.20800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignell R, Root CM, Birse RT, Wang JW, Nässel DR, Winther AM. Presynaptic peptidergic modulation of olfactory receptor neurons in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13070–13075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813004106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johard HAD, Enell LE, Gustafsson E, Trifilieff P, Veenstra JA, Nässel DR. Intrinsic neurons of Drosophila mushroom bodies express short neuropeptide F: relations to extrinsic neurons expressing different neurotransmitters. J Comp Neurol. 2008;507:1479–1496. doi: 10.1002/cne.21636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klagges BRE, Heimbeck G, Godenschwege TA, Hofbauer A, Pflugfelder GO, Reifegerste R, Reisch D, Schaupp M, Buchner S, Buchner E. Invertebrate synapsins: a single gene codes for several isoforms in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 1996;16:3154–3165. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-10-03154.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause E, Wenschuh H, Jungblut PR. The dominance of arginine-containing peptides in MALDI-derived tryptic mass fingerprints of proteins. Anal Chem. 1999;71:4160–4165. doi: 10.1021/ac990298f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder E, Calabrese RL, Nusbaum MP, Trimmer B. Distribution and partial characterization of FMRFamide-like peptides in the stomatogastric nervous system of the rock crab, Cancer borealis, and the spiny lobster Panulirus interruptus. J Comp Neurol. 1987;259:150–163. doi: 10.1002/cne.902590111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meola SM, Sittertz-Bhatkar H. Neuroendocrine modulation of olfactory sensory neuron signal reception via axo-dendritic synapses in the antennae of the mosquito, Aedes aegypti. J Mol Neurosci. 2002;18:239–245. doi: 10.1385/JMN:18:3:239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meola SM, Clottens FL, Holman GM, Nachman RJ, Nichols R, Schoofs L, Wright MS, Olson JK, Hayes TK, Pendleton MW. Isolation and immunocytochemical characterization of three tachykinin-related peptides from the mosquito, Culex salinarius. Neurochem Res. 1998;23:189–202. doi: 10.1023/a:1022432909360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meola SM, Sittertz-Bhatkar H, Pendleton MW, Meola RW, Knight WP, Olson J. Ultrastructural analysis of neurosecretory cells in the antennae of the mosquito, Culex salinarius (Diptera: Culicidae) J Mol Neurosci. 2000;14:17–25. doi: 10.1385/JMN:14:1-2:017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naccarati C, Audsley N, Keen JN, Kim JH, Howell GJ, Kim YJ, Isaac RE. The host-seeking inhibitory peptide, Aea-HP-1, is made in the male accessory gland and transferred to the female during copulation. Peptides. 2012;34:150–157. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2011.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nässel DR. Neuropeptides in the nervous system of Drosophila and other insects: multiple roles of neuromodulators and neurohormones. Progr Neurobiol. 2002;68:1–84. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(02)00057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nässel DR, Winther ÅM. Drosophila neuropeptides in regulation of physiology and behavior. Progr Neurobiol. 2010;92:42–104. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nässel DR, Enell LE, Santos JG, Wegener C, Johard HA. A large population of diverse neurons in the Drosophila central nervous system expresses short neuropeptide F, suggesting multiple distributed peptide functions. BMC Neurosci. 2008;9:90. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-9-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neupert S, Fusca D, Schachtner J, Kloppenburg P, Predel R. Toward a single-cell-based analysis of neuropeptide expression in Periplaneta americana antennal lobe neurons. J Comp Neurol. 2012;520:694–716. doi: 10.1002/cne.22745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Predel R. Peptidergic neurohemal system of an insect: mass spectrometric morphology. J Comp Neurol. 2001;436:363–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Predel R, Rapus J, Eckert M. Myoinhibitory neuropeptides in the American cockroach. Peptides. 2001;22:199–208. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(00)00383-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Predel R, Wegener C, Russell WK, Tichy SE, Russell DH, Nachman RJ. Peptidomics of CNS-associated neurohemal systems of adult Drosophila melanogaster: a mass spectrometric survey of peptides from individual flies. J Comp Neurol. 2004;474:379–392. doi: 10.1002/cne.20145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Predel R, Neupert S, Garczynski SF, Crim JW, Brown MR, Russell WK, Kahnt J, Russell DH, Nachman RJ. Neuropeptidomics of the mosquito Aedes aegypti. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:2006–2015. doi: 10.1021/pr901187p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riehle MA, Garczynski SF, Crim JW, Hill CA, Brown MR. Neuropeptides and peptide hormones in Anopheles gambiae. Science. 2002;298:172–175. doi: 10.1126/science.1076827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Root CM, Ko KI, Jafari A, Wang JW. Presynaptic facilitation by neuropeptide signaling mediates odor-driven food search. Cell. 2011;145:133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos JG, Vömel M, Struck R, Homberg U, Nässel DR, Wegener C. Neuroarchitecture of peptidergic systems in the larval ventral ganglion of Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e695. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachtner J, Schmidt M, Homberg U. Organization and evolutionary trends of primary olfactory brain centers in Tetraconata (Crustacea+Hexapoda) Arthropod Struct Dev. 2005;34:257–299. [Google Scholar]

- Schachtner J, Wegener C, Neupert S, Predel R. Direct peptide profiling of brain tissue by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;615:129–135. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-535-4_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schildberger K, Agricola H. Allatostatin-like immunoreactivity in the brains of crickets and cockroaches. In: Elsner N, Richter DW, editors. Rhythmogenesis in neurons and networks. Stuttgart: Thieme; 1992. p. 489. [Google Scholar]

- Schoofs L, Holman GM, Hayes TK, Nachman RJ, DeLoof A. Locusta-tachykinin I and II, two novel insect neuropeptides with homology to peptides of the vertebrate tachykinin family. FEBS Lett. 1990;261:397–401. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80601-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siju KP, Hansson BS, Ignell R. Immunocytochemical localization of serotonin in the central and peripheral chemosensory system of mosquitoes. Arthropod Struct Dev. 2008;37:248–259. doi: 10.1016/j.asd.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracker TH, Thompson S, Grossman GL, Riehle MA, Brown MR. Characterization of the AeaHP gene and its expression in the mosquito Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) J Med Entomol. 2002;39:331–342. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-39.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terhzaz S, Rosay P, Goodwin SF, Veenstra JA. The neuropeptide SIFamide modulates sexual behavior in Drosophila. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;352:305–310. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utz S, Schachtner J. Development of A-type allatostatin immunoreactivity in antennal lobe neurons of the sphinx moth Manduca sexta. Cell Tissue Res. 2005;320:149–162. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-1059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utz S, Huetteroth W, Wegener C, Kahnt J, Predel R, Schachtner J. Direct peptide profiling of lateral cell groups of the antennal lobes of Manduca sexta reveals specific composition and changes in neuropeptide expression during development. Dev Neurobiol. 2007;67:764–777. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utz S, Huetteroth W, Vömel M, Schachtner J. Mas-allatotropin in the developing antennal lobe of the sphinx moth Manduca sexta: distribution, time course, developmental regulation, and colocalization with other neuropeptides. Dev Neurobiol. 2008;68:123–142. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenstra JA, Costes L. Isolation and identification of a peptide and its cDNA from the mosquito Aedes aegypti related to Manduca sexta allatotropin. Peptides. 1999;20:1145–1151. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(99)00117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenstra JA, Hagedorn HH. Sensitive enzyme immunoassay for Manduca allatotropin and the existence of an allatotropin-immunoreactive peptide in Periplaneta americana. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 1993;23:99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Veenstra JA, Noriega FG, Graf R, Feyereisen R. Identification of three allatostatins and their cDNA from the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Peptides. 1997;18:937–942. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(97)00032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verleyen P, Huybrechts J, Baggerman G, Van Lommel A, De Loof A, Schoofs L. SIFamide is a highly conserved neuropeptide: a comparative study in different insect species. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;320:334–341. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verleyen P, Huybrechts J, Schoofs L. SIFamide illustrates the rapid evolution in arthropod neuropeptide research. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2009;162:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2008.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitzthum H, Homberg U, Agricola H. Distribution of Dip-allatostatin I-like immunoreactivity in the brain of the locust Schistocerca gregaria with detailed analysis of immunostaining in the central complex. J Comp Neurol. 1996;369:419–437. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960603)369:3<419::AID-CNE7>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winther ÅM, Ignell R. Local peptidergic signaling in the antennal lobe shapes olfactory behavior. Fly. 2010;4:2. doi: 10.4161/fly.4.2.11467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winther ÅM, Nässel DR. Intestinal peptides as circulating hormones: release of tachykinin-related peptide from the locust and cockroach midgut. J Exp Biol. 2001;204:1269–1280. doi: 10.1242/jeb.204.7.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwiebel LJ, Takken W. Olfactory regulation of mosquito-host interactions. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;34:645–652. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]