Abstract

The discovery of millions of PIWI–interacting RNAs revealed a fascinating and unanticipated dimension of biology. The PIWI–piRNA pathway has been commonly perceived as germline–specific, even though the somatic function of PIWI proteins was documented when they were first discovered. Recent studies have begun to re–explore this pathway in somatic cells in diverse organisms, particularly lower eukaryotes. These studies have illustrated the multifaceted somatic functions of the pathway not only in transposon silencing but also in genome rearrangement and epigenetic programming, with biological roles in stem–cell function, whole–body regeneration, memory and possibly cancer.

The discoveries of small non-coding RNAs, including PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs), have significantly expanded the RNA world. piRNAs are generally 24–32 nucleotides in length and bind specifically to the PIWI subfamily of Argonaute proteins. Piwi was originally discovered in Drosophila1, in which it functions in germline stem-cell maintenance and self-renewal2. For clarity, we use PIWIs to refer collectively to PIWI proteins, whereas Piwi refers to the individual protein. Although piRNAs were discovered and formally defined in mammalian systems in 2006 as small non-coding RNAs that specifically interact with PIWIs3-6, cloning of piRNAs in Drosophila7-9 revealed that they include a previously discovered class of small non-coding RNAs called repeat-associated RNAs (rasiRNAs)10,11. Since 2006, the PIWI–piRNA field has rapidly advanced, with a focus on the germ line, in which PIWIs and piRNAs are enriched and PIWI mutations lead to a profound infertility phenotype12-14. Indeed, the name PIWI comes from the original mutant phenotype P-element-induced wimpy testis1. The best-known role of the PIWI–piRNA pathway in the germ line is in transposon silencing, because piRNAs map largely to transposable elements9, with PIWI depletion leading to a drastic increase in transposon messenger RNA expression15.

Despite the germline focus, since their discovery, PIWIs’ somatic function has long been documented. Initial work on the Drosophila gene piwi, the first identified member that defines the Argonaute gene family, determined that its germline function depends on the somatic cells of the gonad2. Recently, significant insight into the somatic function of the PIWI–piRNA pathway has come from the ovarian somatic cells of Drosophila. In addition, groundbreaking work in lower eukaryotes has demonstrated a conserved function for PIWIs and their associated piRNAs in somatic tissues — particularly in stem cells. In this Review, we focus on the role of the PIWI–piRNA pathway in the soma of diverse organisms, from basal eukaryotes to humans. We begin by looking at PIWI expression and piRNA biogenesis in somatic tissues, and then illustrate how the PIWI–piRNA pathway exerts diverse functions, including epigenetic regulation, transposon silencing, genome rearrangement and developmental regulation. Through this Review we hope to illustrate a broader role for the PIWI–piRNA pathway in the soma.

Expression of PIWIs and piRNAs in somatic tissues

PIWIs are expressed in organisms from sponges to humans. This expression occurs in remarkably diverse cell types, ranging from naive pluripotent stem cells to differentiated somatic cells, with most somatic expression related to various totipotent and pluripotent stem cells16-24 (Table 1). Several studies have demonstrated an essential stem-cell function for PIWIs. One interesting example comes from planarian stem cells. piwi genes are expressed in planarian totipotent stem cells, called neoblasts, that can repopulate all somatic and germline lineages. Planarians have an unusual regenerative capability, in which neoblasts are responsible for maintaining and regenerating all tissues. PIWIs play a crucial part in the neoblast lineage, as illustrated by the two phenotypic consequences of knockdown of mRNAs encoding PIWIs: first, animals are incapable of body-part regeneration; and second, failure of tissue maintenance ultimately results in death21. Furthermore, piRNA-like small RNAs, which depend on PIWIs for their biogenesis, have been identified in planaria. These RNAs are not germline-restricted, because ablation of the germ line by nanos mRNA knockdown does not affect piRNA-like RNA production21,22. In addition, RNA interference (RNAi) experiments in ascidians have demonstrated the requirement for PIWIs in whole-body regeneration (discussed later)23,24.

Table 1. Piwi orthologue expression.

| Phylum | Common name | Species | Known Piwi genes | PIWI protein expression | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porifera | Sponge | Ephydatia fluviatilis | EfPiwiA and EfPiwiB | Archeocytes (stem cells that differentiate into both somatic and germ cells) |

16 |

| Cnidaria | Jellyfish | Clytia hemisphaerica | Piwi | Somatic stem cells of the tentacle bulb (produce stinging cells characteristic of the cnidarians) |

17 |

| Jellyfish | Podocoryne carnea | Cniwi | Somatic stem cells of the tentacle bulb (see above); striated muscle cells capable of transdifferentiation |

18 | |

| Ctenophora | Comb jellyfish | Pleurobrachia pileus | PpiPiwi1 and PpiPiwi2 | Actively dividing adult somatic cells; germ line | 19 |

| Platyhelminthes | Planaria | Schmidtea mediterranea | smedwi-1, smedwi-2 and smedwi-3 | Neoblasts (totipotent stem cells that can repopulate all somatic and germline lineages) |

21, 22 |

| Saltwater flatworm | Macrostomum lignano | macpiwi | Neoblasts (see above) | 20 | |

| Mollusca | Sea slug | Aplysia californica | Piwi | Nervous system, heart and germ line | 80 |

| Arthropoda | Fruitfly | Drosophila melanogaster | piwi, aub and AGO3 | Gonad, brain, salivary gland | 2, 26, 92, 93 |

| Chordata | Sea squirt (ascidian) |

Botrylloides leachii and Botryllus schlosseri |

Piwi | Stem cell population (capable of whole-body regeneration) | 23, 24 |

| Mouse | Mus musculus | Miwi, Mili and Miwi2 | Diverse cancers (breast cancer, rhabdomyosarcoma, medulloblastoma); male germ line |

12-14, 33 | |

| Human | Homo sapiens | HIWI, HILI, HIWI2 and HIWI3 | Diverse cancers (breast cancer, cervical cancer, endometrial carcinoma, seminomas, hepatocellular carcinoma, gastric cancer, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumours, colon cancer, renal cell carcinoma); haematopoietic stem cells; and male germ line |

30, 32-36 |

Although substantial work has described PIWI expression beyond the germ line of lower eukaryotes, the somatic function of PIWIs was first characterized in somatic cells of the Drosophila ovary. The Drosophila Piwi protein is expressed in all somatic cells within the ovary and in early somatic cells of the testis2,25. Outside the gonad, Piwi binds to polytene chromosomes of the salivary gland26. Emerging and unexpected evidence shows that PIWIs function outside the gonad, particularly in the Drosophila head. The first genetic evidence showed that piwi mutation leads to position effect variegation in the expression of the eye colour gene white in a clonal fashion8,26. This suggests the possibility of cell-autonomous Piwi function in the eye. Direct molecular evidence came from a more recent study in which two Drosophila PIWIs, Argonaute-3 and Aubergine, which were once thought to be germline-specific, showed region-specific expression in the brain, with their mutation leading to transposon upregulation in fly heads27. Interestingly, piRNA-like small RNAs mapping to transposons and heterochromatin are detectable in the Drosophila head on depletion of the RNAi effector Argonaute-2 (ref. 28). A recent publication has shown that all Drosophila PIWIs are expressed during early embryogenesis and that depletion of maternal Drosophila PIWIs results in profound chromosomal and mitotic defects, thus establishing a crucial function for PIWIs in the earliest stage of somatic development29. Together with the work on basal eukaryotes, studies in Drosophila highlight the existence and function of PIWIs in somatic tissues. Although somatic PIWIs clearly function in Drosophila, it remains a mystery whether piRNAs are generated outside the gonad, because some of the most studied piRNA biogenesis factors are not robustly expressed in non-gonadal somatic tissue (discussed later).

In light of the above findings, an important question remains: are PIWIs present in mammalian somatic tissues? There are four human PIWIs: HIWI (also known as PIWIL1), HILI (also known as PIWIL2), HIWI2 (also known as PIWIL4) and HIWI3 (also known as PIWIL3). HIWI is expressed in haematopoietic stem cells but not in their differentiated progeny. Although this once led to the suggestion that HIWI might be involved in the stemness of these stem cells30, a powerful genetic experiment in which all three mouse Piwi genes were knocked out showed no detectable effect on haematopoiesis. Thus, PIWI expression in haematopoietic stem cells may not have any functional implication or PIWI function is redundant with other proteins, possibly Argonaute subfamily proteins31. With regards to human health, many studies demonstrate PIWI expression in a wide variety of human cancers; however, these data are at best correlative and it is too early to tell whether PIWIs have any role in cancer (discussed later)32-36.

The expression of PIWIs in mammalian somatic tissues implies the potential existence of somatic piRNAs. One study provided evidence of piRNA expression in diverse somatic tissues of both the mouse and macaque37. However, the lack of appropriate negative controls combined with a small library size make it difficult to differentiate between true piRNA expression and contamination during library preparation. Indeed, this study might be a cautionary tale describing the challenges in the search for mammalian somatic piRNAs. Further work will help to determine whether piRNAs are expressed outside the germ line in mammals. Perhaps malignant tissues are good sites to begin the search given the expression of PIWIs in cancer.

piRNA biogenesis in the Drosophila ovarian soma

Our mechanistic understanding of somatic piRNA biogenesis comes from recent work in the somatic follicle cells of the Drosophila ovary. piRNAs in the ovarian soma are generated by a Piwi-dependent mechanism through the primary piRNA biogenesis pathway38,39. This process is independent of the other two Drosophila PIWIs, Aubergine and Argonaute-3, which function as a piRNA amplification loop in the germline cells (known as secondary piRNA biogenesis). In the primary piRNA biogenesis pathway, long piRNA precursors are transcribed from specific genomic loci known as piRNA clusters, cleaved and modified in the cytoplasm, and then transported into the nucleus in complex with Piwi (Fig. 1). Ovarian soma-specific piRNAs are transcribed from two main loci. The flamenco locus contains transposon remnants and encodes a long single-stranded piRNA precursor that is antisense to flamenco’s component transposons. Precursors generated from the flamenco locus target transposons of the gypsy family of long terminal repeat (LTR) transposons, including gypsy, ZAM and idefix38. Another ovarian soma-specific locus, traffic jam, has two functions: the 3′ UTR of its transcript is a substrate for somatic piRNA production, whereas its protein product drives Piwi expression in ovarian somatic cells39.

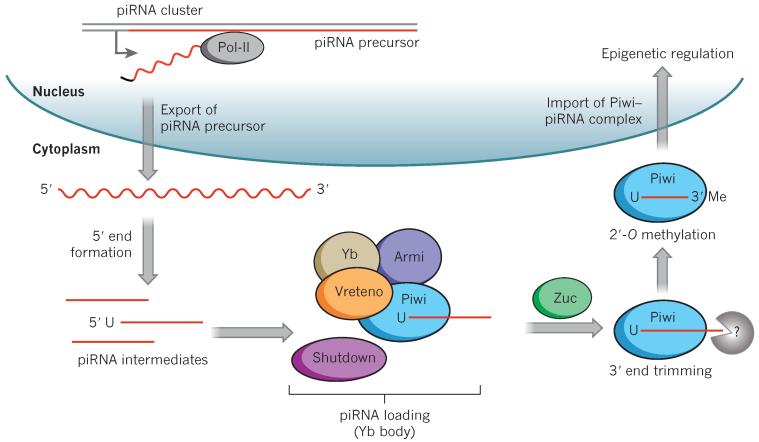

Figure 1. piRNA biogenesis in the Drosophila ovarian soma.

piRNAs are generated from specific genomic loci known as piRNA clusters, which include flamenco, the 5′ UTRs of mRNAs and traffic jam in the soma. The long single-stranded piRNA precursor (red) is then exported from the nucleus. In the cytoplasm, the precursors are processed into mature piRNAs. The precursors are cleaved by an unknown endonuclease to generate their 5′ end, and transported into the perinuclear Yb body for further processing. The precursors are loaded onto Piwi in a process that is dependent on Yb, Armitage (Armi) and Vreteno. Overlapping proteins indicate protein–protein interaction. The co-chaperone Shutdown plays an uncharacterized, but crucial, part in piRNA loading. The putative endonuclease Zucchini (Zuc) is required for piRNA maturation and for nuclear localization of Piwi. Subsequently, piRNAs are trimmed to the appropriate length by an unidentified exonuclease and 2′-O-methylated at the piRNA 3′ end, rendering them more stable. The Piwi–piRNA complex is then transported into the nucleus, where it modulates chromatin state.

It is unclear how long single-stranded piRNA precursors are exported from the nucleus and how these precursors are initially processed into smaller fragments in the cytoplasm. One proposed, but unproven, candidate for piRNA 5′ end determination is Zucchini, an outer mitochondrial membrane protein with single-strand-specific endonuclease activity in vitro40. In Drosophila, the maturing precursor then enters the perinuclear Yb body41-43, an ovarian soma-specific cytoplasmic structure named after the Yb protein44. Although it is not yet clear what occurs in the Yb body, several of its components are crucial for the processing of piRNA precursors into mature piRNAs, and for subsequent Piwi nuclear localization. These components include the helicase Armitage41-43 and the TUDOR-domain-containing protein Vreteno44. Both Vreteno45 and Yb41,43 are needed for Piwi expression and/or stability. Zucchini also functions in piRNA maturation. Knockdown of the mRNA encoding Zucchini in a Drosophila ovarian somatic cell line leads to cytoplasmic accumulation of piRNA-intermediate-like molecules46 and accumulation of Piwi in the Yb body; correspondingly, nuclear Piwi is absent42. The mouse homologues of the above piRNA biogenesis factors, including Zucchini47, Armitage48,49, Shutdown50,51 and Vreteno52 are crucial for piRNA biogenesis in the testes, and male mutants are infertile, thus implying conservation of these factors in piRNA biogenesis.

Next, piRNAs are loaded onto Piwi in the cytoplasm through an uncharacterized step that is independent of Piwi slicer activity and nuclear localization signal39,53. The co-chaperone Shutdown, which is essential to piRNA biogenesis in both the ovarian soma and germ line, may function in piRNA loading54. Ovarian somatic piRNAs contain a characteristic 5′ U, but the mechanism generating this 5′ U bias is unknown. It is possible that Piwi itself preferentially binds RNAs with 5′ U, as is the case for silkworm Piwi in vitro55. This might authenticate and stabilize piRNA intermediates with 5′ U for further processing. An unknown protein then trims the 3′ ends of the maturing piRNAs. The shared structure of Argonaute family proteins suggests the possibility that piRNA length may be determined by the number of bases protected within Piwi56-58. This also explains the characteristic size profile of piRNAs bound by each of the three Drosophila PIWIs9. Mature piRNAs are then 2′-O-methylated by a conserved methyltransferase, Pimet59, perhaps to ensure their stability. Finally, in an uncharacterized step, the Piwi–piRNA complex is imported into the nucleus to exert its regulatory function.

Epigenetic regulation by the PIWI–piRNA pathway

Strong evidence indicates that Piwi and piRNAs play a crucial part in epigenetic regulation. Pioneering work has shown that Piwi functions in the transcriptional silencing of Adh transgene arrays, and small RNAs have been proposed to have a role in Piwi-mediated silencing60. Piwi is a predominantly nuclear protein25 that localizes to salivary gland polytene chromosomes in an RNA-dependent manner26, and co-localizes with known epigenetic modifiers such as the Polycomb group proteins61. There is general agreement that Piwi is required for appropriate histone methylation and transcriptional gene silencing, as loss of Piwi in both germ line and soma leads to a decrease in the repressive methylation mark on histone 3 lysine 9 (H3K9)62-66, an increase in RNA Pol II occupancy63-65 and an increase in nascent transcript60,63,66. Indeed, tissue-specific knockdown of Piwi in somatic ovarian follicle cells implicates transcriptional repression as the dominant mode of transposable element control in the soma66.

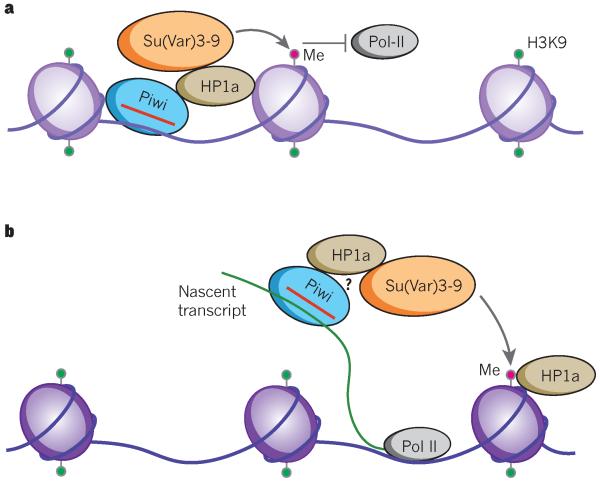

What is the mechanism by which Piwi directs epigenetic modification? The answer to this lies in piRNA, which probably guides Piwi to specific target sequences in the genome by sequence complementarity63-66. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) data from our laboratory suggest that the Piwi–piRNA complex binds its genomic target in euchromatin through a nascent transcript (often a long non-coding RNA), and in heterochromatin predominantly through a direct piRNA-DNA interaction26,64. According to these results, which await reproduction by other labs, the Piwi–piRNA complex then recruits epigenetic factors such as HP1a and the histone methyltransferase Su(var)3-9 to exert their function (Fig. 2). HP1a is a highly conserved chromatin factor whose N-terminal chromodomain binds trimethylated H3K9 whereas the C-terminal chromoshadow domain dimerizes with the same domain in another HP1a molecule and interacts with other proteins64. Piwi may directly recruit HP1a26. HP1a may then recruit one of its well-characterized interactors, Su(var)3-9, which is responsible for most H3K9 methylation in Drosophila64. Alternatively, others have proposed that Piwi may first recruit a histone methyltransferase such as Su(var)3-9 or Setdb1. The methyltransferase could establish H3K9 methylation and in turn recruit HP1a; this possibility is supported by work in fission yeast67. In addition to these core epigenetic factors, Asterix (also known as DmGTSF1), an upstream nuclear factor, is required for Piwi-directed H3K9 methylation68-70. A recently identified downstream effector of Piwi, Maelstrom, is not required for the establishment of H3K9 methylation but is required for the transcriptional silencing of transposable elements63.

Figure 2. Piwi–piRNA mediated epigenetic regulation.

Simplified illustrations of the currently proposed models of Piwi-mediated transcriptional gene silencing. a, In heterochromatin, Piwi may be guided to its target sequences by the complementarity of its bound piRNA (red) to genomic DNA. On binding, Piwi recruits the epigenetic modifier HP1a that then recruits the major Drosophila histone methyltransferase Su(var)3-9, which then deposits a methyl group on the unmethylated histone 3 lysine 9 (H3K9). Through an unknown mechanism, a critical mass of the H3K9 repressive chromatin marks inhibits Pol II transcription, effectively silencing the Piwi–piRNA target. b, In euchromatin, Piwi targets nascent transcripts (green) by piRNA sequence complementarity. Subsequent to this, there are multiple working models. Piwi may directly recruit HP1a, which in turn recruits a histone methyltransferase (Su(var)3-9 is shown) that then deposits methyl groups on the unmethylated H3K9. Alternatively, Piwi may directly recruit the histone methyltransferase, and subsequently HP1a may then bind the methylated H3K9. Regardless of the mechanism, the net effect is that these repressive marks, in concert with Maelstrom (not shown), inhibit RNA Pol II transcription.

Several studies have revealed unanticipated epigenetic gene regulation carried out by Piwi. In Drosophila simulans, maternally deposited piRNAs against the retrotransposon tirant initiated H3K9-mediated transcriptional gene silencing of this element in the somatic tissues of developing embryos71. This study shows that maternal germline-derived piRNAs are required for somatic epigenetic programming. A recent study expanded on this idea by showing that both maternal and zygotic Piwi are required for establishment of heterochromatin in non-gonadal somatic cells of the early embryo72. Interestingly, Piwi-targeting of transposable elements for silencing means that those genes containing or in proximity to transposable element sequences may be piRNA pathway targets. The presence of a transposon or its remnants in an intron or in proximity to a gene correlates with significant transcriptional repression63,69. Surprisingly, Piwi can also act as an epigenetic activator. In Drosophila, Piwi establishes euchromatic features of chromosome 3R telomere-associated sequence (3R-TAS)8, and whole-genome studies have shown that Piwi binding may enhance transcriptional activation marks in multiple regions64. In support of this unexpected epigenetic function, a recent independent study confirmed that piwi mutant flies have increased HP1a enrichment in regions, including 3R-TAS, in which Piwi is implicated as an epigenetic activator72. How can Piwi-binding lead to transcriptional silencing in most target sites, but activation in a small number of target sites? Perhaps Piwi interacts with different partners and/or is influenced by the local chromatin micro-environment or its sublocalization within the nucleus. Clearly, Piwi has many different roles in a variety of cellular processes, and one challenge in the field is to unite or to further distinguish between these many functions.

PIWI–piRNA pathway in genome rearrangement

Ciliates are single-celled organisms that possess remarkable nuclear dimorphism. They have two distinct genomes: a somatic macronucleus that functions in vegetative growth and is actively transcribed, and a transcriptionally silent germline micronucleus that functions in the exchange of genetic information during sexual reproduction, known as conjugation. Following conjugation and mitosis, the zygotic genome in one of the two micronuclei in each daughter cell is extensively edited to create a new and partial somatic genome that replaces the parental germline genome, in a process known as genome rearrangement or, more appropriately, somatic elimination. During somatic elimination, repetitive sequences are removed from the genome before polyploidization, thus preventing their transcription in the resultant macronuclei73. Although other organisms have complex mechanisms for transcriptional and post-transcriptional silencing of transposable elements, the ciliates simply delete such sequences from the somatic macronuclear genome.

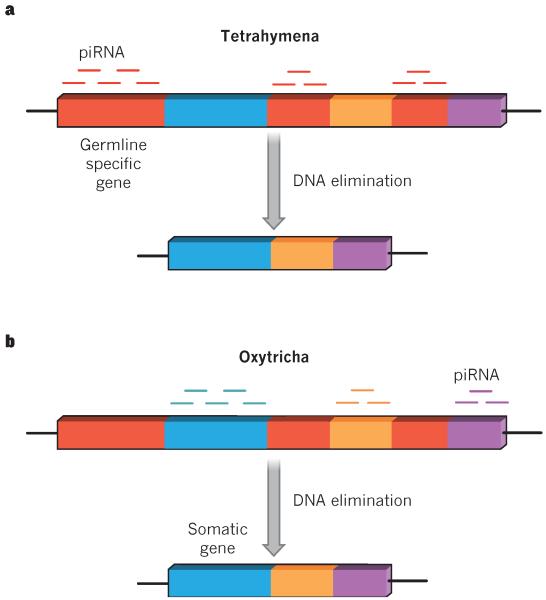

Early studies in the ciliate Tetrahymena revealed that their Piwi orthologues are essential for proper genome rearrangement and piRNA production. These piRNAs, termed scan RNAs in the original literature, are derived from the micronucleus during conjugation. Importantly, Tetrahymena piRNAs are distinct from those in other species as they are produced through a Dicer-dependent mechanism from double-stranded RNA precursors74. In this sense, they are more like endogenous small interfering RNAs75 (endo-siRNAs). After mating, the piRNAs provide sequence-specificity to target germline-restricted regions in the developing somatic macronucleus for elimination (Fig. 3)76; consequent histone methylation then groups these sequences for collective deletion77. In the current model, for which there is strong evidence in both Tetrahymena and Paramecium, long non-coding RNAs transcribed from the parental somatic macronucleus act as sponges for germline-derived piRNAs. Thus, unbound piRNAs specifically mark any non-somatic regions in the genome for elimination in the developing daughter macronucleus78.

Figure 3. Somatic genome rearrangement in ciliates.

Unicellular ciliates posses two nuclei: the germline micronucleus and the somatic macronucleus. After mating, the developing macronucleus is extensively edited to remove germline-specific sequences. The new mature somatic nucleus contains only genes needed for somatic (vegetative) growth. The rest of the germline-specific genome (red boxes) undergoes DNA elimination, an extraordinary method to purge the somatic genome of repetitive sequences and transposons. This process, called somatic genome rearrangement, differs between Tetrahymena and Oxytricha. a, Tetrahymena piRNAs (red lines) are generated by the germ line, and target germline-specific sequences of the developing somatic macronucleus for elimination. b, Oxytricha piRNAs (blue, orange and purple lines) are generated by the parent somatic macronucleus, and direct the retention of somatic genes in the mature somatic macronucleus (blue, orange and purple boxes).

By contrast, piRNAs in the ciliate Oxytricha complex with a Piwi orthologue, Otiwi1, to mark somatic genes for retention during development of the somatic macronucleus. PIWIs are so crucial to Oxytricha that on knockdown of the mRNA encoding Otiwi1 the organisms do not survive after mating. Furthermore, injection of RNAs that target normally deleted genes leads to their retention through multiple sexual generations79. This suggests that genomic composition changes of the somatic macronucleus are heritable across multiple generations. In Tetrahymena, the minority of the developing somatic genome is directed for deletion, whereas in Oxytricha the minority of the developing somatic genome is directed for retention. Although it is not known why these distantly related species solve this puzzle of genome rearrangement in opposite ways, it is clear that each has evolved the most efficient system with the fewest possible piRNA targets to direct the assembly of a complete somatic macronuclear genome79.

PIWI–piRNA pathway in somatic development

The PIWI–piRNA pathway has broad developmental functions in diverse organisms, from memory in the sea slug Aplysia to whole-body regeneration in botryllids. In Aplysia, both synaptic plasticity and associative memory formation require the PIWI–piRNA pathway. Aplysia Piwi, in complex with piRNAs, responds to the neurotransmitter serotonin by directing CpG methylation of the CREB2 promoter. CREB2 is a major inhibitor of memory in Aplysia, so Piwi-mediated transcriptional silencing of CREB2 results in memory through long-lasting, cell-wide enhancement of synaptic transmission80. The capacity of the PIWI–piRNA pathway to epigenetically regulate genes is thus exerted in mature neurons to promote cellular memory, emphasizing PIWI function in differentiated somatic tissue.

Colonial ascidians are chordates that are capable of whole-body regeneration. Remarkably, the ascidian Botrylloides leachii can regenerate its entire body from any blood vessel fragment containing only a few cells. This phenomenon depends on a population of Piwi-positive cells present on the luminal side of the vascular epithelium. On RNAi knockdown of the mRNA encoding Piwi, organisms cannot undergo whole-body regeneration23. In the closely related Botryllus schlosseri, Piwi is also crucial for whole-body regeneration. Piwi positive-cells, which contribute to both the germline and somatic lineages of future generations, reside within the endostyle niche. B. schlosseri undergoes weekly asexual growth, during which a population of Piwi-positive stem cells vacates the original endostyle niche and migrates to the niche within the growing daughter organism before the parent niche undergoes massive apoptosis. In this way, the stem-cell population efficiently preserves itself over the course of the colony’s lifetime through migration to the offspring24.

Piwi suppresses phenotypic variation

The PIWI–piRNA pathway has a direct role in buffering against phenotypic variation, and Piwi depletion in Drosophila results in new somatic defects in a random fashion and at low frequency. Canalization, a term coined by Conrad Waddington in 1942 (ref. 81), describes developmental robustness: the ability of a system to generate a single phenotype regardless of genetic or environmental perturbations. The heat-shock protein Hsp90 is a crucial chaperone in the suppression of phenotypic variation, that is, in canalization. Depletion of Hsp90 generates diverse somatic phenotypic variants in species ranging from Arabidopsis82 to Drosophila83. These variants are heritable even in the absence of heat shock or other forms of stress, and even on repletion of the wild-type Hsp90 levels in progeny, indicating that the effect is not simply due to the chaperone function of Hsp90 during stress. Drosophila Piwi forms a complex with Hsp90 and the heat-shock organizing protein, Hop, in vivo to suppress phenotypic variation84.

This buffering of variation is probably accomplished through both genetic and epigenetic mechanisms. Evidence for a genetic mechanism stems from a study in which Hsp90 depletion in Drosophila leads to defective transposable element silencing by the PIWI–piRNA pathway. The resultant transposon-mediated mutagenesis may generate new phenotypes85. However, the transposon mutagenesis hypothesis cannot explain the full spectrum of canalization phenotypes. Although one copy of maternal piwi is sufficient for transposon silencing, it is insufficient to suppress phenotypic variation84. In addition, maternal epigenetic factors, such as the trithorax group of genes that maintain active chromatin, also buffer against phenotypic variation in Drosophila86. These observations indicate the involvement of an epigenetic mechanism in suppressing phenotypic variation. With regards to the inheritance of such phenotypes, work in the Caenorhabditis elegans germ line has shown that piRNAs induce transgenerational epigenetic inheritance87. Regardless of the mechanism, the PIWI–piRNA pathway clearly functions to suppress expression of new phenotypes and to maintain developmental robustness in Drosophila.

The uncertain meaning of PIWI in cancer

Cancer stem cells may help to explain resistance to cancer treatment and relapse after treatment in certain forms of cancer. Thus, great interest exists in developing our understanding of the basic biology of cancer stem cells and in identifying factors that drive their stemness. A large number of studies document the ectopic expression of PIWIs in cancers. This was first reported in seminoma, a testicular germ-cell tumour in which HIWI was drastically overexpressed32. Related to this overexpression, HIWI mapped to a genomic region linked to seminomas and non-seminomas. Since then, PIWI expression has been shown in a variety of somatic cancers: HIWI is expressed in gastric cancer36,88, whereas HILI is expressed in breast cancer, colon cancer, gastrointestinal stromal tumours, renal cell carcinoma and endometrial carcinoma33. Some early studies also suggested that PIWI expression could be used as a prognostic marker35. In both hepatocellular carcinoma34 and soft-tissue sarcoma35, tumour HIWI expression is associated with increased risk of tumour-related death. The discovery of PIWI expression in diverse forms of human somatic cancers opens up a promising area of research, especially given the well-established role of PIWIs in stem-cell maintenance and self-renewal.

Consistent with this notion, HILI enrichment was reported in a cancer cell subpopulation expressing the stemness factors OCT4 and NANOG89. In addition, a large variety of embryonic and developmental genes are expressed in cancers. However, this does not necessarily imply that they have a causative role in tumorigenesis. Such a conclusion will need to be based on functional studies.

At present, such functional studies are scarce. HILI overexpression in a fibroblast cell line activates STAT3 and the antiapoptotic factor BCLX, suggesting that HILI might function as an oncogene33. Genetic studies in Drosophila revealed that piwi mutation attenuates tumour growth in a sensitized lethal (3) malignant brain tumour (l(3)mbt)-mutant background. Other piRNA pathway genes were also upregulated in l(3)mbt tumours. These findings are perhaps the strongest data available at present in correlating ectopic PIWI expression with tumour growth90.

These preliminary mechanistic data are promising, but research on PIWIs in cancer remains at an early stage and is primarily correlative. It is known that insertional mutagenesis by LINE1 elements is common in human epithelial cancers91. Therefore, it is possible that PIWIs are expressed in reaction to increased transposon activity in cancer, and thus act to protect the genome. Perhaps an in vivo overexpression model would be a good starting point to determine whether ectopic or overexpression of a PIWI protein can actually cause cancer, or is merely a consequence of tumorigenesis. Without a doubt, more large-scale, systematic research is needed before we can conclude whether or not human PIWIs have any role in cancer.

Outstanding questions

PIWIs occupy the interface between stem-cell and small RNA biology. They serve diverse roles in diverse tissues, from totipotent stem cells to totally differentiated cell types, from the germ line to the soma. Tantalizing questions remain, including how broadly are PIWIs and piRNAs expressed in mammalian somatic tissues? And, what is their function there, if any? The mammalian soma awaits our rigorous interrogation. At a more fundamental level, what are the molecular mechanisms by which Piwi regulates stemness? Conversely, what exactly is Piwi doing in differentiated tissues? The lower eukaryotes, in which we are making rapid progress on this topic, provide an excellent arena for these investigations.

The reason underlying ectopic expression of PIWIs in many human cancers is still a mystery. Do PIWIs have a role in cancer? If so, do PIWIs provoke dedifferentiation or lend a competitive advantage by enhancing stemness or even as a reactive mechanism to suppress transposition? Finally, are piRNAs ectopically expressed in cancers? If so, what is their function? Answers to these questions will not only shed light on the function of PIWIs and piRNAs but could also mark paths that are ripe for cancer research.

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Christensen, C. Juliano and S. Ramesh Mani for their critical reading of the manuscript. R.J.R. and M.M.W. are supported by an NIH Medical Scientist Training Program grant (T32-GM07205). The current work in the Lin lab on PIWIs and piRNA is supported by the NIH (DP1CA174418 and R01HD42012), the G. Harold & Leila Mathers Foundation, and an Ellison Medical Foundation Senior Scholar Award.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Readers are welcome to comment on the online version of this paper at go.nature.com/mjff5j.

References

- 1.Lin H, Spradling AC. A novel group of pumilio mutations affects the asymmetric division of germline stem cells in the Drosophila ovary. Development. 1997;124:2463–2476. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.12.2463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cox DN, et al. A novel class of evolutionarily conserved genes defined by piwi are essential for stem cell self-renewal. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3715–3727. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.23.3715. This paper reports the discovery of the argonaute/piwi gene family and is the first demonstration of the somatic function of a PIWI protein (for germline stem-cell maintenance).

- 3.Girard A, Sachidanandam R, Hannon GJ, Carmell MA. A germline-specific class of small RNAs binds mammalian Piwi proteins. Nature. 2006;442:199–202. doi: 10.1038/nature04917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aravin A, et al. A novel class of small RNAs bind to MILI protein in mouse testes. Nature. 2006;442:203–207. doi: 10.1038/nature04916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grivna ST, Beyret E, Wang Z, Lin H. A novel class of small RNAs in mouse spermatogenic cells. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1709–1714. doi: 10.1101/gad.1434406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lau NC, et al. Characterization of the piRNA complex from rat testes. Science. 2006;313:363–367. doi: 10.1126/science.1130164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saito K, et al. Specific association of Piwi with rasiRNAs derived from retrotransposon and heterochromatic regions in the Drosophila genome. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2214–2222. doi: 10.1101/gad.1454806. This work defines a somatic piRNA pathway in the Drosophila ovary.

- 8.Yin H, Lin H. An epigenetic activation role of Piwi and a Piwi-associated piRNA in Drosophila melanogaster. Nature. 2007;450:304–308. doi: 10.1038/nature06263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brennecke J, et al. Discrete small RNA-generating loci as master regulators of transposon activity in Drosophila. Cell. 2007;128:1089–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aravin AA, et al. The small RNA profile during Drosophila melanogaster development. Dev. Cell. 2003;5:337–350. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00228-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vagin VV, et al. A distinct small RNA pathway silences selfish genetic elements in the germline. Science. 2006;313:320–324. doi: 10.1126/science.1129333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deng W, Lin H. miwi, a murine homolog of piwi, encodes a cytoplasmic protein essential for spermatogenesis. Dev. Cell. 2002;2:819–830. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00165-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuramochi-Miyagawa S, et al. Mili, a mammalian member of piwi family gene, is essential for spermatogenesis. Development. 2004;131:839–849. doi: 10.1242/dev.00973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carmell MA, et al. MIWI2 is essential for spermatogenesis and repression of transposons in the mouse male germline. Dev. Cell. 2007;12:503–514. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siomi MC, Sato K, Pezic D, Aravin AA. PIWI-interacting small RNAs: the vanguard of genome defence. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011;12:246–258. doi: 10.1038/nrm3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Funayama N, Nakatsukasa M, Mohri K, Masuda Y, Agata K. Piwi expression in archeocytes and choanocytes in demosponges: insights into the stem cell system in demosponges. Evol. Dev. 2010;12:275–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2010.00413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Denker E, Manuel M, Leclere L, Le Guyader H, Rabet N. Ordered progression of nematogenesis from stem cells through differentiation stages in the tentacle bulb of Clytia hemisphaerica (Hydrozoa, Cnidaria) Dev. Biol. 2008;315:99–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seipel K, Yanze N, Schmid V. The germ line and somatic stem cell gene Cniwi in the jellyfish Podocoryne carnea. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2004;48:1–7. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.15005568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alié A, et al. Somatic stem cells express Piwi and Vasa genes in an adult ctenophore: ancient association of “germline genes” with stemness. Dev. Biol. 2011;350:183–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Mulder K, et al. Stem cells are differentially regulated during development, regeneration and homeostasis in flatworms. Dev. Biol. 2009;334:198–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reddien PW, Oviedo NJ, Jennings JR, Jenkin JC, Sanchez Alvarado A. SMEDWI-2 is a PIWI-like protein that regulates planarian stem cells. Science. 2005;310:1327–1330. doi: 10.1126/science.1116110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palakodeti D, Smielewska M, Lu YC, Yeo GW, Graveley BR. The PIWI proteins SMEDWI-2 and SMEDWI-3 are required for stem cell function and piRNA expression in planarians. RNA. 2008;14:1174–1186. doi: 10.1261/rna.1085008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rinkevich Y, et al. Piwi positive cells that line the vasculature epithelium, underlie whole body regeneration in a basal chordate. Dev. Biol. 2010;345:94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.05.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rinkevich Y, et al. Repeated, long-term cycling of putative stem cells between niches in a basal chordate. Dev. Cell. 2013;24:76–88. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cox DN, Chao A, Lin H. piwi encodes a nucleoplasmic factor whose activity modulates the number and division rate of germline stem cells. Development. 2000;127:503–514. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.3.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brower-Toland B, et al. Drosophila Piwi associates with chromatin and interacts directly with HP1a. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2300–2311. doi: 10.1101/gad.1564307. This paper shows the direct interaction between Piwi and HP1a, the binding of Piwi to chromosomes in Drosophila somatic cells and the epigenetic effect of such interaction and binding.

- 27.Perrat PN, et al. Transposition-driven genomic heterogeneity in the Drosophila brain. Science. 2013;340:91–95. doi: 10.1126/science.1231965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghildiyal M, et al. Endogenous siRNAs derived from transposons and mRNAs in Drosophila somatic cells. Science. 2008;320:1077–1081. doi: 10.1126/science.1157396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mani SR, Megosh H, Lin H. PIWI proteins are essential for early Drosophila embryogenesis. Dev. Biol. 2013 Oct 31; doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.10.017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharma AK, et al. Human CD34+ stem cells express the hiwi gene, a human homologue of the Drosophila gene piwi. Blood. 2001;97:426–434. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.2.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nolde MJ, Cheng EC, Guo S, Lin H. Piwi genes are dispensable for normal hematopoiesis in mice. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e71950. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qiao D, Zeeman AM, Deng W, Looijenga LH, Lin H. Molecular characterization of hiwi, a human member of the piwi gene family whose overexpression is correlated to seminomas. Oncogene. 2002;21:3988–3999. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee JH, et al. Stem-cell protein Piwil2 is widely expressed in tumors and inhibits apoptosis through activation of Stat3/Bcl-XL pathway. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006;15:201–211. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao YM, et al. HIWI is associated with prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. Cancer. 2012;118:2708–2717. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taubert H, et al. Expression of the stem cell self-renewal gene Hiwi and risk of tumour-related death in patients with soft-tissue sarcoma. Oncogene. 2007;26:1098–1100. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu X, et al. Expression of hiwi gene in human gastric cancer was associated with proliferation of cancer cells. Int. J. Cancer. 2006;118:1922–1929. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yan Z, et al. Widespread expression of piRNA-like molecules in somatic tissues. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:6596–6607. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malone CD, et al. Specialized piRNA pathways act in germline and somatic tissues of the Drosophila ovary. Cell. 2009;137:522–535. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.040. This work delineates distinct germline and somatic piRNA pathways in the Drosophila ovary.

- 39.Saito K, et al. A regulatory circuit for piwi by the large Maf gene traffic jam in Drosophila. Nature. 2009;461:1296–1299. doi: 10.1038/nature08501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ipsaro JJ, Haase AD, Knott SR, Joshua-Tor L, Hannon GJ. The structural biochemistry of Zucchini implicates it as a nuclease in piRNA biogenesis. Nature. 2012;491:279–283. doi: 10.1038/nature11502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olivieri D, Sykora MM, Sachidanandam R, Mechtler K, Brennecke J. An in vivo RNAi assay identifies major genetic and cellular requirements for primary piRNA biogenesis in Drosophila. EMBO J. 2010;29:3301–3317. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saito K, et al. Roles for the Yb body components Armitage and Yb in primary piRNA biogenesis in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2493–2498. doi: 10.1101/gad.1989510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qi H, et al. The Yb body, a major site for Piwi-associated RNA biogenesis and a gateway for Piwi expression and transport to the nucleus in somatic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:3789–3797. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.193888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Szakmary A, Reedy M, Qi H, Lin H. The Yb protein defines a novel organelle and regulates male germline stem cell self-renewal in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Cell Biol. 2009;185:613–627. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Handler D, et al. A systematic analysis of Drosophila TUDOR domain-containing proteins identifies Vreteno and the Tdrd12 family as essential primary piRNA pathway factors. EMBO J. 2011;30:3977–3993. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nishimasu H, et al. Structure and function of Zucchini endoribonuclease in piRNA biogenesis. Nature. 2012;491:284–287. doi: 10.1038/nature11509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Watanabe T, et al. MITOPLD is a mitochondrial protein essential for nuage formation and piRNA biogenesis in the mouse germline. Dev. Cell. 2011;20:364–375. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zheng K, et al. Mouse MOV10L1 associates with Piwi proteins and is an essential component of the Piwi-interacting RNA (piRNA) pathway. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:11841–11846. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003953107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frost RJ, et al. MOV10L1 is necessary for protection of spermatocytes against retrotransposons by Piwi-interacting RNAs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:11847–11852. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007158107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiol J, et al. A role for Fkbp6 and the chaperone machinery in piRNA amplification and transposon silencing. Mol. Cell. 2012;47:970–979. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Crackower MA, et al. Essential role of Fkbp6 in male fertility and homologous chromosome pairing in meiosis. Science. 2003;300:1291–1295. doi: 10.1126/science.1083022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pandey RR, et al. Tudor domain containing 12 (TDRD12) is essential for secondary PIWI interacting RNA biogenesis in mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2013;110:16492–16497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316316110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Darricarrère N, Liu N, Watanabe T, Lin H. Function of Piwi, a nuclear Piwi/Argonaute protein, is independent of its slicer activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:1297–1302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213283110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Olivieri D, Senti KA, Subramanian S, Sachidanandam R, Brennecke J. The cochaperone shutdown defines a group of biogenesis factors essential for all piRNA populations in Drosophila. Mol. Cell. 2012;47:954–969. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kawaoka S, Izumi N, Katsuma S, Tomari Y. 3′ end formation of PIWI-interacting RNAs in vitro. Mol. Cell. 2011;43:1015–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Parker JS, Roe SM, Barford D. Crystal structure of a PIWI protein suggests mechanisms for siRNA recognition and slicer activity. EMBO J. 2004;23:4727–4737. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boland A, Huntzinger E, Schmidt S, Izaurralde E, Weichenrieder O. Crystal structure of the MID-PIWI lobe of a eukaryotic Argonaute protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:10466–10471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103946108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nakanishi K, Weinberg DE, Bartel DP, Patel DJ. Structure of yeast Argonaute with guide RNA. Nature. 2012;486:368–374. doi: 10.1038/nature11211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saito K, Sakaguchi Y, Suzuki T, Siomi H, Siomi MC. Pimet, the Drosophila homolog of HEN1, mediates 2′-O-methylation of Piwi-interacting RNAs at their 3′ ends. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1603–1608. doi: 10.1101/gad.1563607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pal-Bhadra M, Bhadra U, Birchler JA. RNAi related mechanisms affect both transcriptional and posttranscriptional transgene silencing in Drosophila. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:315–327. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00440-9. This is the first demonstration that Piwi is essential for transcriptional and post-transcriptional gene silencing.

- 61.Grimaud C, et al. RNAi components are required for nuclear clustering of Polycomb group response elements. Cell. 2006;124:957–971. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pal-Bhadra M, et al. Heterochromatic silencing and HP1 localization in Drosophila are dependent on the RNAi machinery. Science. 2004;303:669–672. doi: 10.1126/science.1092653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sienski G, Donertas D, Brennecke J. Transcriptional silencing of transposons by Piwi and Maelstrom and its impact on chromatin state and gene expression. Cell. 2012;151:964–980. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Huang XA, et al. A major epigenetic programming mechanism guided by piRNAs. Dev. Cell. 2013;24:502–516. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.01.023. This work demonstrates that piRNAs are both necessary and sufficient to recruit Piwi and epigenetic factors to target sites and presents a whole-genome analysis of Piwi binding.

- 65.Le Thomas A, et al. Piwi induces piRNA-guided transcriptional silencing and establishment of a repressive chromatin state. Genes Dev. 2013;27:390–399. doi: 10.1101/gad.209841.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rozhkov NV, Hammell M, Hannon GJ. Multiple roles for Piwi in silencing Drosophila transposons. Genes Dev. 2013;27:400–412. doi: 10.1101/gad.209767.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ge DT, Zamore PD. Small RNA-directed silencing: the fly finds its inner fission yeast? Curr. Biol. 2013;23:R318–R320. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Muerdter F, et al. A genome-wide RNAi screen draws a genetic framework for transposon control and primary piRNA biogenesis in Drosophila. Mol. Cell. 2013;50:736–748. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ohtani H, et al. DmGTSF1 is necessary for Piwi-piRISC-mediated transcriptional transposon silencing in the Drosophila ovary. Genes Dev. 2013;27:1656–1661. doi: 10.1101/gad.221515.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dönertas D, Sienski G, Brennecke J. Drosophila Gtsf1 is an essential component of the Piwi-mediated transcriptional silencing complex. Genes Dev. 2013;27:1693–1705. doi: 10.1101/gad.221150.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Akkouche A, et al. Maternally deposited germline piRNAs silence the tirant retrotransposon in somatic cells. EMBO Rep. 2013;14:458–464. doi: 10.1038/embor.2013.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gu T, Elgin SCR. Maternal depletion of Piwi, a component of the RNAi system, impacts heterochromatin formation in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003780. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schoeberl UE, Mochizuki K. Keeping the soma free of transposons: programmed DNA elimination in ciliates. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:37045–37052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.276964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mochizuki K, Gorovsky MA. A dicer-like protein in Tetrahymena has distinct functions in genome rearrangement, chromosome segregation, and meiotic prophase. Genes Dev. 2005;19:77–89. doi: 10.1101/gad.1265105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Okamura K, Lai EC. Endogenous small interfering RNAs in animals. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:673–678. doi: 10.1038/nrm2479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mochizuki K, Fine NA, Fujisawa T, Gorovsky MA. Analysis of a piwi-related gene implicates small RNAs in genome rearrangement in tetrahymena. Cell. 2002;110:689–699. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00909-1. This demonstrates that a PIWI protein is required for DNA elimination/rearrangement in Tetrahymena.

- 77.Taverna SD, Coyne RS, Allis CD. Methylation of histone h3 at lysine 9 targets programmed DNA elimination in tetrahymena. Cell. 2002;110:701–711. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00941-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Aronica L, et al. Study of an RNA helicase implicates small RNA-noncoding RNA interactions in programmed DNA elimination in Tetrahymena. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2228–2241. doi: 10.1101/gad.481908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fang W, Wang X, Bracht JR, Nowacki M, Landweber LF. Piwi-interacting RNAs protect DNA against loss during Oxytricha genome rearrangement. Cell. 2012;151:1243–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rajasethupathy P, et al. A role for neuronal piRNAs in the epigenetic control of memory-related synaptic plasticity. Cell. 2012;149:693–707. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.057. This work reports an epigenetic function for the PIWI–piRNA pathway in the Aplysia neural system.

- 81.Waddington CH. Canalization of development and the inheritance of acquired characters. Nature. 1942;150:563–565. doi: 10.1038/1831654a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Queitsch C, Sangster TA, Lindquist S. Hsp90 as a capacitor of phenotypic variation. Nature. 2002;417:618–624. doi: 10.1038/nature749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rutherford SL, Lindquist S. Hsp90 as a capacitor for morphological evolution. Nature. 1998;396:336–342. doi: 10.1038/24550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gangaraju VK, et al. Drosophila Piwi functions in Hsp90-mediated suppression of phenotypic variation. Nature Genet. 2011;43:153–158. doi: 10.1038/ng.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Specchia V, et al. Hsp90 prevents phenotypic variation by suppressing the mutagenic activity of transposons. Nature. 2010;463:662–665. doi: 10.1038/nature08739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sollars V, et al. Evidence for an epigenetic mechanism by which Hsp90 acts as a capacitor for morphological evolution. Nature Genet. 2003;33:70–74. doi: 10.1038/ng1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ashe A, et al. piRNAs can trigger a multigenerational epigenetic memory in the germline of C. elegans. Cell. 2012;150:88–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Grochola LF, et al. The stem cell-associated Hiwi gene in human adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: expression and risk of tumour-related death. Br. J. Cancer. 2008;99:1083–1088. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lee JH, et al. Pathways of proliferation and antiapoptosis driven in breast cancer stem cells by stem cell protein Piwil2. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4569–4579. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Janic A, Mendizabal L, Llamazares S, Rossell D, Gonzalez C. Ectopic expression of germline genes drives malignant brain tumor growth in Drosophila. Science. 2010;330:1824–1827. doi: 10.1126/science.1195481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lee E, et al. Landscape of somatic retrotransposition in human cancers. Science. 2012;337:967–971. doi: 10.1126/science.1222077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Harris AN, Macdonald PM. Aubergine encodes a Drosophila polar granule component required for pole cell formation and related to eIF2C. Development. 2001;128:2823–2832. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.14.2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Li C, et al. Collapse of germline piRNAs in the absence of Argonaute3 reveals somatic piRNAs in flies. Cell. 2009;137:509–521. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]