Abstract

APD334 was discovered as part of our internal effort to identify potent, centrally available, functional antagonists of the S1P1 receptor for use as next generation therapeutics for treating multiple sclerosis (MS) and other autoimmune diseases. APD334 is a potent functional antagonist of S1P1 and has a favorable PK/PD profile, producing robust lymphocyte lowering at relatively low plasma concentrations in several preclinical species. This new agent was efficacious in a mouse experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) model of MS and a rat collagen induced arthritis (CIA) model and was found to have appreciable central exposure.

Keywords: Sphingosine-1-phosphate, S1P1, APD334, gilenya, FTY720, fingolimod

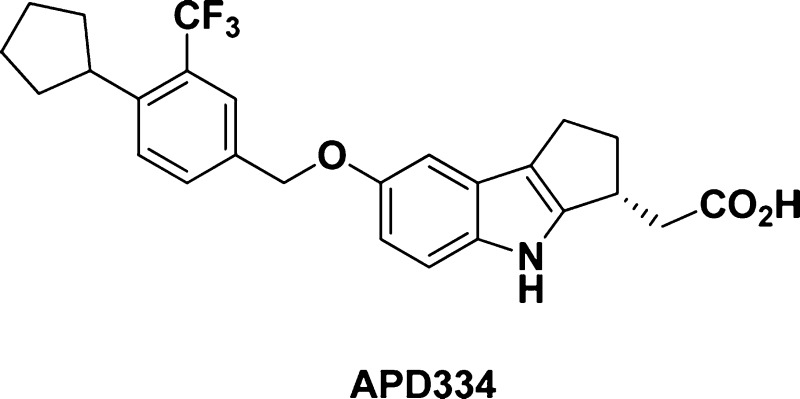

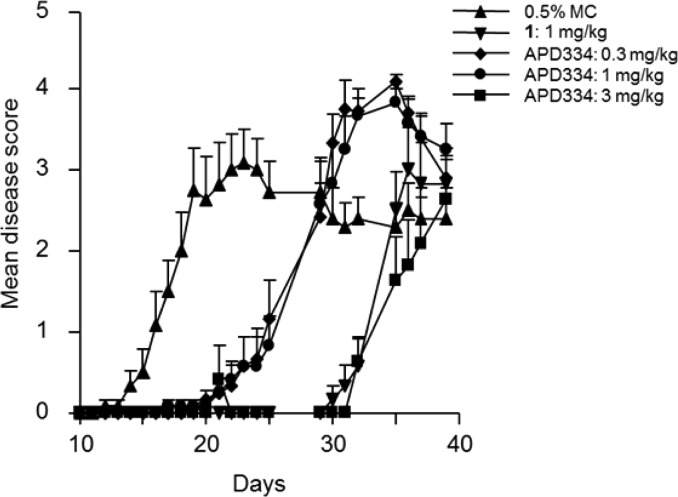

Sphingosine-1-phosphate-1 (S1P1) is a Class A G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) expressed on lymphocytes, neural cells, and the endothelium.1 This receptor belongs to a family of five GPCRs (S1P1–5), which recognize the sphingolipid sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) and collectively perform a variety of functions, with S1P1 regulating vascular development and lymphocyte trafficking.2 Gilenya (1, fingolimod) (Figure 1) is an oral medication that targets the S1P receptors and is indicated for the treatment of relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS).3In vivo, fingolimod is phosphorylated by sphingosine kinase to the (S)-monophosphate (2), which is an agonist of four of the five S1P receptors (S1P1, S1P3, S1P4, and S1P5).4 Sustained activation (agonism) of lymphocyte expressed S1P1 results in internalization and proteasomal degradation of this receptor, thus resulting in “functional antagonism” of S1P1.5 Reduced S1P1 expression interrupts the normal trafficking of lymphocytes and retains autoreactive lymphocytes in the lymph nodes and thymus,6 thus preventing their accumulation in the brain and spinal cord of MS patients. Additionally, fingolimod readily passes through the blood–brain barrier and is believed to reduce neuroinflammation through direct action on S1P1 expressed on astrocytes.7,8 The unique biology associated with the S1P1 receptor has encouraged others to identify alternative agents for treatment of autoimmune disease.9

Figure 1.

Structures of gilenya, monophosphate 2, 5-phenyl-1,2,4-oxadiazole 3, and APD334.

Monophosphate 2 is also a potent agonist of S1P3, S1P4, and S1P5, but the relative contribution of these subtypes to efficacy in humans is unclear. S1P5 is expressed on oligodendrocytes and its activation on human brain endothelial cells improves barrier integrity and reduces transendothelial monocyte migration.10 S1P4 is expressed on hematopoietic, lymphocytic, and dendritic cells and the loss of this receptor has been shown to reduce TH17 differentiation of TH cells.11 TH17 cells are associated with MS pathogenesis, and populations of this cell type in MS patients are typically increased.12 Reduced interaction with S1P3 has been a consistent theme in the literature, as this receptor was believed to be responsible for the transient bradycardia observed in humans treated with fingolimod. It is now understood that in humans at least, this cardiovascular event more likely results from S1P1-dependent G protein gated inwardly rectifying potassium (GIRK) channel activation on human atrial myocytes.13,14 Regardless, S1P3-sparing agonists may still be desirable, as nonselective S1P1 agonists are associated with pro-fibrotic responses via S1P2- and S1P3-dependent signaling.15,16

Identification of new agents with reduced elimination half-life has been sought after, as full lymphocyte recovery following fingolimod treatment requires >5 weeks and could be a complicating factor in the event of opportunistic infection.17 In addition, teratogenicity has been observed in rodents, and the long half-life in humans (8 days) requires contraception for two months after stopping treatment.18 A further challenge is identifying therapeutics with appreciable central exposure as this is believed to be necessary for success in treating MS.19 Lastly, new agents with reduced hepatotoxicity in humans would be highly beneficial. Herein we report the discovery of APD334 (4, Figure 1), a centrally available, selective, functional antagonist of the S1P1 receptor currently in development for the treatment of autoimmune disease.

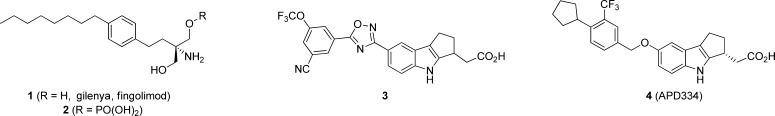

Our early efforts to identify a functional antagonist with a competitive pharmacodynamic profile focused on optimization of 5-phenyl-1,2,4-oxadiazoles (e.g., 3, Figure 1).20,21 Despite discovery of several potent and selective analogues, we failed to identify a compound with good activity in the mouse lymphocyte lowering (LL) experiment at an acceptable plasma concentration (e.g., 3 LL IC50 = 1.62 μM). Furthermore, 3 was undetectable in rat brain and CSF after 24 h intravenous infusion. To improve these parameters, we investigated a related series of 7-benzyloxy analogues (e.g., 7–21). These racemic mixtures were prepared from 5 utilizing the synthetic sequence outlined in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

Internalization of S1P1 is preceded by activation of the receptor (agonism); thus, EC50 values were generated in a homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence (HTRF) cyclase assay to assess engagement of the receptor (Table 1). Compound 7 was the first analogue prepared and possesses the CN/OCF3 substitution pattern previously identified as a potency driver in the 1,2,4-oxadiazole structure–activity relationship (SAR) (e.g., 3, S1P1 EC50 = 1.1 nM). This aryl motif, however, was less well tolerated in the benzyloxy series (7, S1P1 EC50 = 16 nM). Instead, the analogous R1 and R2 disubstituted benzene was preferred (9, S1P1 EC50 = 1.7 nM). Subsequent SAR focused on the R2 group and revealed a preference for larger alkyl groups. In particular, cyclopentyl and cyclohexyl were optimal in terms of potency (13–15). Several of these analogues were examined in an acute mouse lymphocyte lowering experiment measuring lymphocyte count and plasma concentration at 24 h following a single 1.0 mg/kg oral dose. This abbreviated pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamics (PK/PD) analysis suggested 15 may offer a significant improvement in in vivo potency relative to 3 and prompted characterization of each enantiomer independently.

Table 1. Racemic 7-Benzyloxy SAR (human S1P1, HTRF cAMP).

| compd | R1 | R2 | R3 | EC50, nM (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | CN | OCF3 | 16.0 (90%) | |

| 8 | CF3 | CF3 | 26.0 (98%) | |

| 9 | CN | OCF3 | 1.7 (109%) | |

| 10 | CN | OCH3 | 120 (136%) | |

| 11 | CF3 | CN | 141 (104%) | |

| 12 | CF3 | Cl | 159 (117%) | |

| 13 | CN | cyclohexyl | 0.087 (98%) | |

| 14 | CF3 | cyclohexyl | 0.077 (96%) | |

| 15 | CF3 | cyclopentyl | 0.073(104%) | |

| 16 | CF3 | cyclobutyl | 0.45 (109%) | |

| 17 | CF3 | cyclopropyl | 3.68 (118%) | |

| 18 | CF3 | n-propyl | 0.49 (107%) | |

| 19 | CF3 | neopentyl | 55.8 (112%) | |

| 20 | CF3 | iso-butyl | 0.44 (103%) | |

| 21 | CF3 | methylcyclohexyl | 4.58 (111%) |

EC50 values are the mean of three or more replicates. Value in parentheses is the % agonism relative to S1P. S1P EC50 = 0.062 nM; 2 EC50 = 0.006 nM (101%).

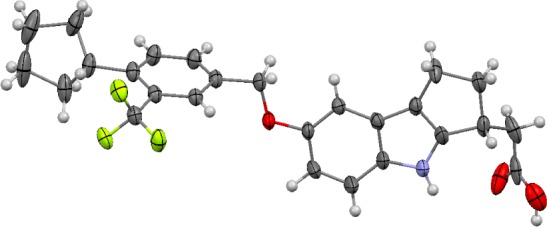

An enantiomeric separation was performed, and both isomers were tested in the S1P1 HTRF assay. Each isomer was very active in vitro, with one offering a moderate potency advantage (i.e., hS1P1 EC50 = 0.04 nM, Emax = 102% versus 0.09 nM, Emax = 103%). A single crystal of the more potent enantiomer was grown from a saturated acetone/acetonitrile solution, and the absolute stereochemistry was determined by X-ray to be S. Correspondingly, an X-ray structure proof was also obtained for the R-isomer (Figure 2, 4, APD334). The R-isomer was ultimately selected as the development candidate in part due to superior stability in rat liver microsomes (t1/2 > 60 min versus t1/2 = 9 min for the S-isomer). Instability of the S-isomer was anticipated to complicate testing in rat disease models, PK experiments, and toxicity studies. Of note, both enantiomers were observed to be stable in human liver microsomes (t1/2 > 60 min). In addition to improved rat microsomal stability, the R-isomer (APD334) forms a crystalline, high melting, nonhygroscopic, anhydrous l-arginine salt, which was regarded as a significant development advantage given the difficulty in identifying other suitable salt forms for either enantiomer. Interestingly, the crystalline free acid prepared for the X-ray determination was observed to possess similarly good physical properties; however, this crystal form was not orally bioavailable in rats when dosed as an aqueous suspension. This contrasts with the amorphous free acid form of 4, which demonstrated good bioavailability when dosed as a suspension (%F = 54). Importantly, the l-arginine salt achieved good exposure levels in SD rat when dosed orally as a solution in sterile water (Cmax = 0.361 μg/mL, 1.0 mg/kg equivalent).

Figure 2.

Mercury 3.1 Development (Build RC5) ellipsoid rendition22 of X-ray crystal structure of (R)-2-(7-((4-cyclo-pentyl-3-(trifluoromethyl)benzyl)oxy)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-cyclopenta[b]indol-3-yl)acetic acid [4, APD334].

S1P1 functional data for five species was obtained, as well as EC50 values for the five human S1P subtypes (Table 2). S1P1 activity was maintained in all preclinical species examined, and APD334 was devoid of any agonism or antagonism at human S1P2 and S1P3. Furthermore, moderate agonism at human S1P4 and S1P5 was observed but is reduced relative to S1P1, both in terms of potency and efficacy. The extent to which 4 internalizes human S1P1 was evaluated in CHO cells expressing HA tagged S1P1, and 4 was found to have an IC50 value of 1.88 nM.

Table 2. APD334 in Vitro S1P1 Preclinical Species EC50 Data and Human S1P1-5 EC50 Values.

| preclinical species S1P1 EC50 cAMP, nM (Emax %) |

human S1P1–5 EC50 β-arrestin,

nM (Emax %) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| human | mouse | rat | dog | monkey | S1P1 | S1P2 | S1P3 | S1P4 | S1P5 |

| 0.093 (103) | 0.44 (95) | 0.32 (99) | 0.34 (87) | 0.32 (95) | 6.10 (110) | >10,000 | >10,000 | 147 (63) | 24.4 (73) |

APD334 is stable in mouse, rat, dog, monkey, and human liver microsomes (t1/2 > 60 min), and iv/po PK studies were performed in all preclinical species (Table 3). Consistent with the in vitro data, APD334 has a relatively low systemic clearance (<4% of hepatic blood flow) and high Cmax across all species. In both dog and monkey a significant decrease in volume of distribution (Vss) was observed relative to rodent. Oral bioavailability was in the range of 40–100%, and the terminal phase half-life varied from 6 h in monkey, to as long as 29 h in dog. Rat and monkey t1/2 values for siponimod (another S1P1 modulator currently in human trials) have been disclosed and are 6 and 19 h, respectively.23

Table 3. APD334 Preclinical Species Pharmacokinetics and in Vivo Lymphocyte Lowering (LL) IC50 Valuesa.

| species | dose iv/po (mg/kg) | Clsys (L/h/kg)b | %LBF | Vss(L/kg)b | Cmax (μg/mL) | tmax (h) | AUC0-inf (μg·h/mL) | t1/2 po (h) | %F | LL IC50 (μM)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mouse | 1/1 | 0.110 | 2.00 | 1.93 | 0.780 | 8.00 | 10.3 | 12.3 | 100 | 0.101 |

| rat | 1/1 | 0.145 | 3.45 | 1.61 | 0.218 | 7.33 | 3.79 | 9.64 | 54.0 | 0.051 |

| dog | 1/3 | 0.0138 | 0.746 | 0.609 | 3.71 | 7.33 | 164.0 | 28.8 | 73.2 | 0.058 |

| monkey | 1/3 | 0.0568 | 2.23 | 0.411 | 2.87 | 3.33 | 23.1 | 6.37 | 43.8 | 0.098 |

Amorphous APD334 (vide infra) was dosed as a suspension in 0.5% methyl cellulose.

Clsys and Vss were determined by intraveneous administration.

Values were generated from a full 24 h time course of drug effect on lymphocyte lowering (LL).

Peripheral lymphocyte counts were measured over a 24 h time course following oral administration of APD334, in order to establish a PK/PD relationship. Lymphocyte lowering (LL) IC50 values were calculated, which illustrated that relatively low blood concentrations (0.051 to 0.101 μM) are required to produce substantial lymphopenia in all species (Table 3). Notably, the calculated LL IC50 values reflect total plasma concentration wherein APD334 is highly protein bound (97.8% human, 98.0% rat).

Constant infusion CNS distribution studies in male Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats were performed and APD334 was observed to have improved central exposure relative to its predecessor 3. After a 48 h constant infusion (14.5 μg/h/kg), APD334 reached a brain concentration of 0.21 μM, which is approximately twice that of the plasma concentration (0.11 μM) and translates to a brain-to-plasma (B/P) ratio of 1.9. Drug plasma concentration at the 48 h time point is 2-fold higher than the estimated rat lymphocyte lowering IC50 value (0.051 μM).

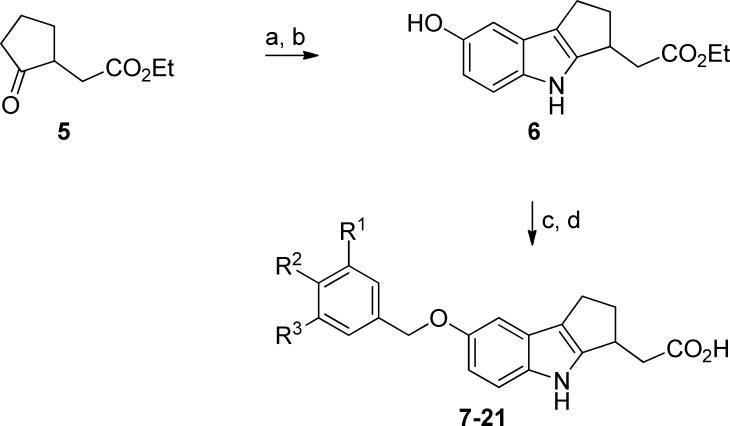

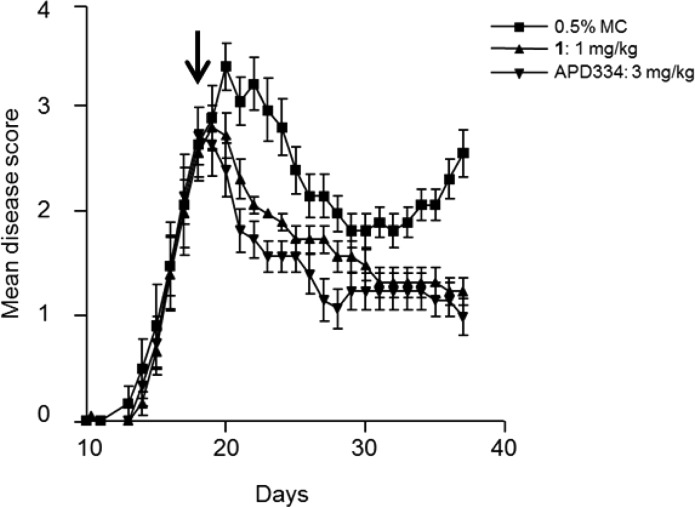

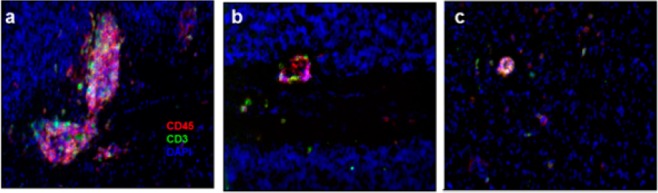

APD334 was evaluated in a murine experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) model.24 This model mimics MS by inducing a demyelinating autoimmune response by utilizing myelin/oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG35–55) as autoantigen. Prophylactically, APD334 prevented the onset and severity of disease relative to vehicle up to day 25, at which time dosing was discontinued. All treatment arms went on to develop severe disease as shown by their clinical scores (Figure 3). Therapeutic administration of APD334 was also examined (Figure 4). Treatment began at day 18, by which time all animals had developed severe disease, and APD334 was administered out to day 37. APD334 reversed disease relative to vehicle and was similar to the efficacy observed with fingolimod (1). Furthermore, histological examination of spinal cord and brain collected on day 37 revealed significantly fewer inflammatory foci compared to vehicle control, and a marked decrease in number of infiltrating lymphocytes was also observed (Figure 5).

Figure 3.

Prophylactic mouse experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE): female C57Bl/6 mice, vehicle = 0.5% methylcellulose (MC); q.d. dosing began on day 3 and continued to day 25.

Figure 4.

Therapeutic mouse experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE): female C57Bl/6 mice, vehicle = 0.5% methylcellulose (MC); q.d. beginning on day 18 and the arrow indicates the start of drug treatment.

Figure 5.

Immunofluorescent staining of cerebellum of therapeutically treated mice at 37 days postimmunization. Pink color indicates CD45+ T-cells, green CD3+ T-cells, and blue 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole fluorescent stain (DAPI): (a) 0.5% methylcellulose; (b) 1.0 mg/kg 1; (c) 3.0 mg/kg APD334.

APD334 was similarly efficacious in a collagen induced arthritis (CIA) model. Prophylactic oral administration in female Lewis rats resulted in a significant reduction in ankle diameters (mean ± SEM) on the day 17 end point following a daily oral dose of 1.0 and 3.0 mg/kg (0.2803 ± 0.00570 and 0.2690 ± 0.0031 in., versus 0.3352 ± 0.0045 for vehicle) and weight regain (178.6 ± 4.1 and 182.3 ± 1.9 g, versus 160.3 ± 2.3 for vehicle) and was similar to that observed in rats treated with 1.0 mg/kg of fingolimod (0.2694 ± 0.0039 in., 181.9 ± 2.2 g) or 0.075 mg/kg of methotrexate (0.2795 ± 0.0066 in., 181.7 ± 2.9 g). Improvement in histological parameters in the knees and ankles of CIA rats was also observed, suggesting that inhibiting lymphocyte entry into arthritic joints with APD334 treatment suppresses CIA in rodents.

CYP inhibition IC50 values were determined, and APD334 has a very low inhibitory potential (i.e., 3A4, 2D6, 2C9, 1A2, 2C19; IC50 >50 μM), thus ruling out the likelihood of a drug–drug interaction. Selectivity was further examined in a broad panel of receptors, ion channels, and enzymes. APD334 exhibited weak or no activity, in more than 100 different binding and functional assays. The most potent off target interaction observed was for the human adenosine A3 receptor, which afforded an IC50 value of 3.3 μM in the A3 binding assay. Activation of inward-rectifying potassium channel (IKAch) expressed on human atrial myocytes was subsequently examined in vitro. APD334 and S1P were tested and were found to have EC50 values of 29.9 and 2.1 nM, respectively.

Genotoxic potential was evaluated in an Ames bacterial reverse mutation assay, and APD334 was nonmutagenic both with and without rat liver S9 activation. [3H]-Astemizole binding and cardiac repolarization (patch clamp) assays ruled out any hERG channel interaction (IC50 > 30 μM, respectively), and APD334 was subsequently evaluated in telemeterized dog. No changes in pulse pressure, heart rate, body temperature, or ECG parameter were observed at dose levels up to 40 mg/kg dose.

CNS and respiratory safety studies were performed in SD rats. No neurobehavioral effects or changes in respiratory function were observed up to the top dose of 350 mg/kg in both studies. Finally, a 14 day repeat dose rat toxicity assay was conducted using 30, 100, 300, and 1000 mg/kg does groups. APD334 was well tolerated up to 300 mg, with mortality and CNS clinical signs observed at the 1000 mg/kg dose. In a separate study, APD334 was found to be dose proportional up to 300 mg/kg in SD rat with high levels of exposure at the top doses (Cmax = 135.7 μM at 300 mg/kg, and Cmax = 182.7 μM at 1000 mg/kg) suggesting a comfortable safety window versus the pharmacologically effective plasma concentration of 0.051 μM in rat. Lastly, no safety related findings with respect to liver function were observed in rat.

In summary, we identified APD334, a structurally novel, selective, functional antagonist of S1P1, which met our preclinical safety and efficacy criteria. Importantly, APD334 achieves good central exposure following oral dosing and possesses a favorable pharmacokinetic profile in multiple preclinical species. APD334 is currently in development for a number of indications related to autoimmune disease. The outcome of these studies and plans for future development will be reported in due course.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- PPTS

pyridinium p-toluenesulfonate

- DIEA

diisopropylethylamine

- DMF

dimethylformamide

- DIAD

diisopropyl azodicarboxylate

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

- CNS

central nervous system

- hERG

human ether-à-go-go-related gene

- ECG

electrocardiogram

- CHO

chinese hamster ovary

- CYP

cytochrome P450

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

Supporting Information Available

Synthesis and analytical data for compounds 7–21 and APD334. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- O’Sullivan C.; Dev K. K. The Structure and Function of the S1P1 Receptor. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2013, 34, 401–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann V. Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Receptors in Health and Disease: Mechanistic Insights from Gene Deletion Studies and Reverse Pharmacology. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 115, 84–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun J.; Brinkman V. A Mechanistically Novel, First Oral Therapy for Multiple Sclerosis: The Development of Fingolimod (FTY720, Gilenya). Discovery Med. 2011, 12, 213–228. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale J. J.; Yan L.; Neway W. E.; Hajdu R.; Bergstrom J. D.; Milligan J. A.; Shei G.-J.; Chrebet G. L.; Thornton R. A.; Card D.; Rosenbach M.; Rosen H.; Mandala S. Synthesis, Stereochemical Determination and Biochemical Characterization of the Enantiomeric Phosphate Esters of the Novel Immunosuppressive Agent FTY720. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004, 12, 4803–4807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oo M. L.; Thangada S.; Wu M.-T.; Liu C. H.; Macdonald T. L.; Lynch K. R.; Lin C.-Y.; Hla T. Immunosuppressive and Anti-angiogenic Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Receptor-1 Agonists Induce Ubiquitinylation and Proteasomal Degradation of the Receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 9082–9289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matloubian M.; Lo C. G.; Cinamon G.; Lesneski M. J.; Xu Y.; Brinkmann V.; Allende M. L.; Proia R. L.; Cyster J. G. Lymphocyte Egress from Thymus and Peripheral Lymphoic Organs is Dependent on S1P Receptor 1. Nature 2004, 427, 355–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun J.; Hartung H.-P. Mechanism of Action of Oral Fingolimod (FTY720) in Multiple Sclerosis. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2010, 33, 91–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J. W.; Gardell S. E.; Herrr D. R.; Rivera R.; Lee C.-W.; Noguchi K.; Teo S. T.; Yung Y. C.; Lu M.; Kennedy G.; Chun J. FTY720 (Fingolimod) Efficacy in an Animal Model of Multiple Sclerosis Requires Astrocyte Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Receptor 1 (S1P1) Modulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011, 108, 751–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyckman A. J. Recent Advancements in Discovery and Development of Sphingosine-1-Phosphate-1 Receptor Agonists. Annu. Rep. Med. Chem. 2012, 47, 195–207. [Google Scholar]

- Van Doorn R.; Lopes Pinheiro M. A.; Kooij G.; Lakeman K.; von het hof B.; van der Pol S.; Geerts D.; van Horssen J.; van der Valk P.; van der Kam E.; Ronken E.; Reijerkerk A.; de Vries H. E. Sphingosine 1-phosphate Receptor 5 Mediates the Immune Quiescence of the Human Brain Endothelial Barrier. J. Neuroinflamm. 2012, 10, 1186/1742–2094–9-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze T.; Golfier S.; Tabeling C.; Rabel K.; Graler M.; Witzenrath M.; Lipp M. Sphingosine-1-phosphate Receptor 4 (S1P4) Deficiency Profoundly Affects Dendritic Cell Function and TH17-cell Differentiation in a Murine Model. FASEB J. 2011, 25, 4024–4036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadidi-Niaragh F.; Mirshafiey A. The Th17 Cell, the New Player of Neuroinflammatory Process in Multiple Sclerosis. Scand. J. Immunol. 2011, 74, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyrakh L.; Roman M. I.; Brinkmann V.; Wickman K. The Heart Rate Decrease Caused by Acute FTY720 Administration is Mediated by the G Protein-Gated Potassium Channel I IKACh. Am. J. Transplant. 2005, 5, 529–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gergely P.; Nuesslein-Hildesheim B.; Guerni D.; Brinkmann V.; Traebert M.; Bruns C.; Pan S.; Gray N. S.; Hinterding K.; Cooke N. G.; Groenewegen A.; Vitaliti A.; Sing T.; Luttringer O.; Yang J.; Gardin A.; Wang N.; Crumb W. J. Jr.; Saltzman M.; Rosenberg M.; Wallstrom E. The Selective Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Receptor Modulator BAF312 Redirects Lymphocyte Distribution and Has Species-Specific Effects on Heart Rate. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 167, 1035–1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katrin S.; Menyhart K.; Killer N.; Renault B.; Bauer Y.; Studer R.; Steiner B.; Bolli M. H.; Nayler O.; Gatfield J. Sphinosine 1-Phosphate (S1P) Receptor Agonists Mediate Pro-fibrotic Responses in Normal Human Lung Fibroblasts via S1P2 and S1P3 Receptors and Smad-independent Signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 14839–14851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takuwa N.; Okamoto Y.; Yoshioka K.; Takuwa Y. Sphingosine-1-phosphate Signaling and Cardiac Fibrosis. Inflamm. Regen. 2013, 33, 96–108. [Google Scholar]

- Kovarik J. M.; Schmouder R.; Barilla R.; Riviere G.-J.; Wang Y.; Hunt T. Multiple-Dose FTY720: Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics, and Lymphocyte Responses in Healthy Subjects. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 44, 532–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier D.; Hafler D. A. Fingolimod for Multiple Sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 339–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demont E.; Arpino S.; Bit R.; Campbell C.; Deeks N.; Desai S.; Dowell S.; Gaskin P.; Gray J.; Harrison L.; Haynes A.; Heightman T.; Holmes D.; Humphreys P.; Kumar U.; Morse M.; Osborne G.; Panshal T.; Philpott K.; Taylor S.; Watson R.; Willis R.; Witherington J. Discovery of a Brain-penetrant S1P3-sparing Direct Agonist of the S1P1 and S1P5 Receptors Efficacious at Low Oral Dose. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 6724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzard D.; Han S.; Thorsen L.; Moody J.; Lopez L.; Kawasaki A.; Schrader T.; Sage C.; Gao Y.; Edwards J.; Barden J.; Thatte J.; Fu L.; Soloman M.; Liu L.; Al-Shamma H.; Gatlin J.; Le M.; Xing C.; Espinola S.; Jones R. M. Discovery and Characterization of Potent and Selective 4-Oxo-4-(5-(5-phenyl-1,2,4-oxadiazol-3-yl)indolin-1-yl)butanoic acids as S1P1 Agonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 6013–6018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzard D.; Han S.; Lopez L.; Kawasaki A.; Moody J.; Thoresen L.; Ullman B.; Lehmann J.; Calderon I.; Zhu X.; Gharbaoui T.; Sengupta D.; Krishnan A.; Gao Y.; Edwards J.; Barden J.; Morgan M.; Usmani K.; Chen C.; Sadeque A.; Thatte J.; Solomon M.; Fu L.; Whelan K.; Liu L.; Al-Shamma H.; Gatlin J.; Le M.; Xing C.; Espinola S.; Jones R. M. Fused Tricyclic Indoles as S1P1 Agonists with Robust Efficacy in Animal Models of Autoimmune Disease. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 4404–4409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macrae C. F.; Bruno I. J.; Chisholm J. A.; Edgington P. R.; McCabe P.; Pidcock E.; Rodriguez-Monge L.; Taylor R.; van de Streek J.; Wood P. A. Mercury CSD 2.0: New Features for the Visualization and Investigation of Crystal Structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2008, 41, 466–470. [Google Scholar]

- Pan S.; Gray N. S.; Gao W.; Mi Y.; Fan Y.; Wang X.; Tuntland T.; Che J.; Lefebvre S.; Chen Y.; Chu A.; Hinterding K.; Gardin A.; End P.; Heining P.; Bruns C.; Cooke N. G.; Nuesslein-Hildesheim B. Discovery of BAF312 (Siponimod), a P0tent and Selective S1P Receptor Modulator. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 4, 333–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantinescu C. S.; Farooqi N.; O’Brien K.; Gran B. Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis (EAE) as a Model for Multiple Sclerosis (MS). Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 164, 1079–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.