Abstract

Since 1979, US federal appropriations bills have prohibited the use of federal funds from covering abortion care for Peace Corps volunteers. There are no exceptions; unlike other groups that receive health care through US federal funding streams, including Medicaid recipients, federal employees, and women in federal prisons, abortion care is not covered for volunteers even in cases of life endangerment, rape, or incest. We interviewed 433 returned Peace Corps volunteers to document opinions of, perceptions about, and experiences with obtaining abortion care. Our results regarding the abortion experiences of Peace Corps volunteers, especially those who were raped, bear witness to a profound inequity and show that the time has come to lift the “no exceptions” funding ban on abortion coverage.

Since its creation in 1961, more than 215 000 Americans have served in the US Peace Corps.1 Dedicated to increasing capacity in participating countries, promoting a better understanding of Americans by peoples served, and promoting a better understanding of other peoples by Americans, Peace Corps volunteers have served in 139 countries. Currently 63% of volunteers are women, more than 90% are single, and the average age at the initiation of service is 28 years.1

Volunteers typically serve in-country for 2 years, with the possibility of a third year extension, after a rigorous selection process and a 3-month preservice training. Peace Corps volunteers receive a stipend to cover living expenses, which varies by location but is currently around $250 to $300 per month, and a readjustment allowance of roughly $7500 after completion of service. Volunteers also receive their health care, including prescription medications, routine examinations, and emergency care, free of charge; most services are provided in-country through a Peace Corps Medical Officer. When necessary, volunteers also receive health care services through regional medical facilities or in Washington, DC, after medical evacuation.

Since 1979 US federal appropriations bills have restricted the coverage of abortion for Peace Corps volunteers. There are no exceptions to the coverage ban. Other groups who receive health care through US federal funding streams, including Medicaid recipients, federal employees (including employees of the Peace Corps) and their dependents, residents of the District of Columbia, women who receive health services through the Indian Health Service, and women in federal prisons, are all, as matter of policy, eligible to receive abortion coverage in cases when the pregnancy threatens the life of the woman or is the result of rape or incest.2 In December 2012, the passage of the “Shaheen Amendment” to the FY2013 National Defense Authorization Act extended these same coverage benefits to military personnel and their dependents. However, for Peace Corps volunteers, abortion services are not covered even in these narrow circumstances.3

Because volunteers are at risk for sexual assault, often serve in countries where abortion is legally restricted, and receive stipends that are minimal, these restrictions might be acutely devastating.4,5 A body of research has documented the considerable impact that Medicaid funding restrictions have had on low-income women.6–8 More recently, research on the experiences of US military personnel helped build the case for extending coverage for abortion in cases of rape and incest.9–12 However, no published literature currently exists that explores the opinions, perceptions, or experiences of Peace Corps volunteers with respect to abortion care. Our study addresses this gap.

To better understand the impact of the funding restrictions on Peace Corps volunteers and contextualize those experiences within the larger frame of reproductive health service delivery, we conducted a large-scale qualitative study with returned Peace Corps volunteers (RPCVs). Specifically, our study aimed to document the reproductive health and abortion experiences of RPCVs; explore RPCVs’ current knowledge of the abortion funding restrictions as well as the information provided about the policy at time of service; understand better RPCVs’ opinions about the funding restrictions and efforts to expand coverage in cases of life endangerment, rape, or incest; and identify ways in which reproductive health services could be improved.

METHODS

Our goal was to conduct in-depth, semi-structured, open-ended interviews with as many RPCVs as possible within a 2-month data collection window in June to August 2013. RPCVs were eligible to participate if they had served between 1979 and 2013 (inclusive) and were not currently in service. There were no eligibility restrictions with respect to age, gender, sexual orientation, country of service, or personal experiences regarding abortion or reproductive health care. We recruited participants by posting ads on social media, circulating information through listservs, and establishing a study Web site.

Interviews

Using an interview guide created specifically for this study, we conducted our interviews, which averaged 60 minutes and were audio recorded with participant consent, over the telephone and Skype. The principal investigator (A. F.) conducted 109 interviews; the Study Coordinator (G. A.) and 4 additional interviewers conducted the other 324 interviews after being trained by the principal investigator. As a token of our gratitude, we offered participants a $20 gift certificate to Amazon.com.

The interviewer took detailed notes during the interview and then immediately summarized and field coded data using FluidSurveys. We later transcribed audio-recorded interviews verbatim and used ATLAS.ti 6.2 software (Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany) to manage the transcripts, notes, and summaries. Data analysis was an iterative process in which the study team appraised emerging categories and themes throughout data collection to define codes, draw meaning, and establish thematic saturation, a process guided by regular team meetings. We conducted content and thematic analyses of interview content using predetermined codes and categories and inductive techniques to identify emergent themes. To protect the confidentiality of our participants we have used pseudonyms throughout this article and have removed or masked all personally identifying information.

Participants

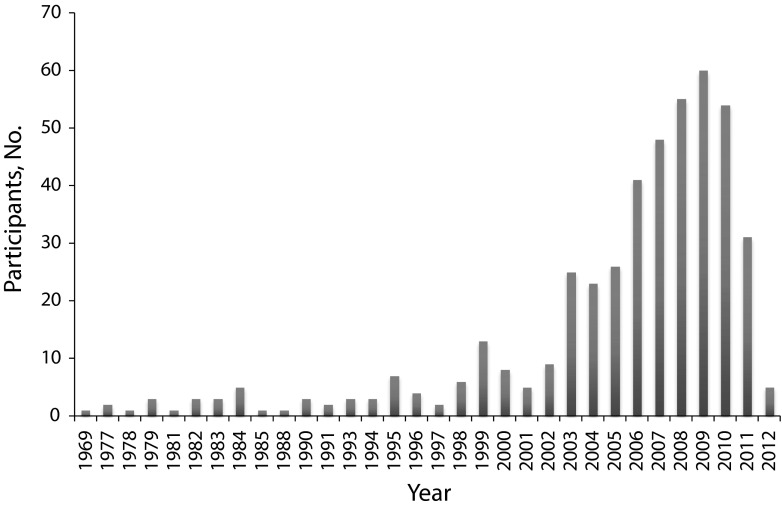

Over the 2-month data collection period we conducted 433 interviews with RPCVs. Eighty-three percent of participants identified as female (n = 362) and 17% as male; the overwhelming majority of our participants were in their 20s and unmarried when they served. Participants identified as being from 47 US states and Washington, DC. As shown in Figure 1, our participants initiated their service throughout the eligibility period (1969–2013), and the majority served in the last decade. Because some RPCVs served in the Peace Corps more than once, there were a small number of volunteers who began one of their service periods before our eligibility period. Finally, our participants served in 83 different countries (Figure 2), reflective of all regions in which the Peace Corps operates.

FIGURE 1—

Initial year of service of participants: documenting the abortion experiences of US Peace Corps Volunteers, June–August 2013.

Note. Not all years are presented on the graph because participants did not initiate service in all years.

FIGURE 2—

Countries of service (shaded): documenting the abortion experiences of US Peace Corps Volunteers, June–August 2013.

Of the 362 women who participated in our study, 18 (5.0%) reported a personal abortion experience while in service. Twenty-seven participants (6.2%), including several who also discussed their own abortion experience, reported on at least 1 abortion experience of someone else. Thus, 10.4% of our interviews included a detailed discussion of at least 1 abortion experience. Thirty-two women (8.8%) reported at least 1 personal experience of rape or sexual assault; several of these women described having been raped 2 or more times by different perpetrators. Moreover, 140 participants (32.3%) reported on the rape or sexual assault experience of someone else. Although there were cases in which several participants talked about the same event, over the course of the study we heard about at least 43 different abortion experiences and 125 different sexual assault and rape experiences. Consistent with the years of service of our participants, the majority of events described took place in the first decade of the 21st century.

RESULTS

Prior to the ban on the funding of abortion care in all circumstances that came into effect in 1979, abortion was covered through the Peace Corps health system as a medical procedure. Volunteers were able to contact the Peace Corps and arrange to have an abortion in-country, if a trained provider was available, and were not required to pay for the service, regardless of the circumstances surrounding the pregnancy. As demonstrated in “Susan’s Story,” volunteers were able to return to service relatively quickly, in as little as a week after the procedure.

Susan’s Story: Abortion Care Before 1979

Prior to the implementation of the funding ban, Susan was serving in Central Asia and became pregnant after consensual sex. She had been using an IUD at the time and notified the Peace Corps Medical Officer (PCMO) early in her first trimester. The PCMO asked her to travel from her village to the capital as soon as possible; Susan soon made the 2-day journey. Although no one in the Peace Corps Medical Office performed abortions, the PCMO was able to identify a physician who had trained in Britain and was able to provide safe, legal care. Susan obtained her abortion in the capital without incident and was able to return to her village and resume her service after less than a week. The Peace Corps paid for all elements of her abortion care, including her transportation to the capital and the costs of the procedure itself, just as it would have for any other medical service (interview conducted July 2013).

Abortion Care After the Ban

Our interviews with women who had abortions in the first decade after the funding ban went into effect suggest that the early years of implementation were especially challenging. In the 1980s, a volunteer who chose to terminate a pregnancy would be medically evacuated to the United States and was expected to arrange and pay for the abortion herself, with little support or guidance from the Peace Corps.

April’s Story: Abortion Care in the 1980s

April and her husband joined the Peace Corps together in the mid-1980s. Prior to their departure for South America, all volunteers in their cohort were given a number of live vaccines and other medications. The Peace Corps medical team informed the group that the pre-departure regimen could cause significant fetal anomalies and asked all of the women if there was a chance they could be pregnant. April was diligent about taking her oral contraceptive pills and didn’t believe there was any possibility of her being pregnant.

April didn’t have a period for 2 months after her arrival in-country. Although she wasn’t especially concerned—she had experienced amenorrhea in the past—she contacted the PCMO who then had her take a pregnancy test using a blood sample; the results were negative. However, 2 months later, April felt a “kicking” sensation in her abdomen and she knew that she was pregnant. She immediately went to the capital and learned after an ultrasound that she was 21 weeks into her pregnancy. Her husband soon joined her in the capital and they were told that to obtain an abortion, April would be medically evacuated to Washington, DC. The Peace Corps would cover flight expenses and her accommodations while in DC, but she would have to pay for the abortion herself, even though her monthly stipend was only $50. Her husband was not permitted to go with her and remain in service. Once arriving in DC, April described the process this way:

I came up to the United States in my flip-flops and sundress in October when it was really cold, and I got to the airport in DC and there was no one to meet me. . . . I found my way to the Peace Corps office and I was brought into a room with a nurse who said basically “We’re sorry to tell you but Reagan is the President right now and we can’t touch this with a ten foot pole. We can’t help you and you’ll have to figure this one out for yourself.” And I said, “Well, could you at least give me names of clinics or hospitals or whatever that will provide an abortion?” and they gave me a phone book and said “We can’t help you in any way.” And it was unbelievable. It was just horrible. And I spent 3 days [trying to find a provider], I had no idea what to do.

With the logistical and financial support of family members, April ultimately was able to find a hospital in New York that provided later abortion care. Her parents paid for the procedure, which cost $1200, the equivalent of 2 years of April’s stipend. She spent nearly a month in the United States before being able to return to her country of service and rejoin her husband (interview conducted July 2013).

By the early 1990s, the process by which volunteers were able to obtain abortion care had changed. Although the funding restrictions still required women to pay out-of-pocket for the abortion itself, women were no longer simply handed a phone book on arrival. Our participants who obtained abortions in the United States in the 1990s and 2000s were generally more satisfied with the systems that had been put into place than volunteers who obtained abortions in the years immediately after the ban went into effect.

Linda’s Story: Abortion Care in the 2000s

In the early 2000s, Linda was serving in East Asia when she became pregnant during her leave. Upon returning to her country of service Linda contacted her PCMO and explained that she suspected she was pregnant. After her positive pregnancy test, Linda was informed that she would not be able to remain in the Peace Corps if she was pregnant; before the end of her first trimester she would be medically evacuated to the United States. If she chose to continue the pregnancy, she would return to her home of record and the Peace Corps, through the bridge health insurance system, would cover her prenatal and delivery care. However, if she wanted to talk about her options, she would be medically evacuated to Washington, DC where she would be able to speak with a counselor. If she chose to have an abortion she would need to pay for it out-of-pocket and would likely remain in DC for a month; if she was medically cleared she could return to service.

Linda elected to return to DC and have an abortion. When she arrived in DC she met with a Peace Corps nurse who referred her to an outside social worker for counseling. Linda expressed her desire to terminate the pregnancy and she was provided with information about area clinics. She felt incredible relief at being able to have a safe termination; her partner joined her in DC at his own expense and she felt well supported. Because she was early in her pregnancy, the abortion cost around $300, and her boyfriend, who was not in the Peace Corps, covered the costs. She described the Peace Corps personnel with whom she interacted, both in-country and in DC, as nonjudgmental and professional. In hindsight, she thinks it is terrible that abortion was not covered like other medical procedures, but at the time she did not even think about that; she was just grateful to be able to have an abortion and return to complete her service. Cognizant of the political dynamics surrounding abortion in the United States she doesn’t expect that abortion care, irrespective of reason, will be funded for volunteers anytime soon. But she describes the lack of coverage in cases of life endangerment, rape, or incest as “blatantly wrong” and “antiquated” (interview conducted July 2013).

Although April’s and Linda’s experiences differed in many ways from a procedural perspective, neither participant was aware of the policies surrounding abortion until she became pregnant. Indeed, the experiences of women who reported an abortion while in service, and most of the abortion experiences that were reported by others, suggest that knowledge of the policy is not widespread; the majority of women who had abortions learned about the policy only after they became pregnant. However, women who reported having abortions more recently were generally provided with counseling options and referrals to service providers.

Both April and Linda were able to cover the cost of the abortion itself with support from loved ones. However, a theme that emerged in our interviews was the challenge that women experienced paying for their abortions, particularly given their small stipends. Women who did not want to disclose the abortion to family members or did not have a partner who could afford to pay for the abortion (for example, women who became pregnant after consensual sex with another volunteer or a host country national) and who didn’t have independent means, experienced challenges paying out-of-pocket. As a participant explained, “I got a comfortable monthly stipend to be living in those local conditions, but there’s no way that that stipend would have been enough for me to obtain a safe abortion.” Only in recent years have some volunteers been offered the option of drawing against their readjustment allowance as a way of covering the costs of the abortion procedure.

As both April’s and Linda’s stories reveal, the process of obtaining an abortion and then medically clearing to return to service takes about a month; the Peace Corps covers the expenses related to the medical evacuation itself and the cost of staying in the United States during that period. Although women who were able to return to service after an abortion generally expressed relief at being able to do so, the length of time away was concerning for some of our participants, both with respect to their projects and with respect to confidentiality; others at the site or in their cohort inevitably knew (or at least suspected) that the volunteer had left to have an abortion. As one noted:

If somebody leaves for, you know, a month or 2, and goes to DC and comes back . . . it just doesn’t take much of a stretch of the imagination to kind of figure out what it was that happened to that volunteer. So, as far as being able to maintain confidentiality, I don’t know how Peace Corps could say that they had actually done that.

Finally, another overall theme that emerged from women’s abortion experiences was the issue of social support, or the lack thereof. Because Linda’s partner was not a volunteer and was based in the United States he was able to be with her in Washington, DC, when she had the procedure. However, her experience was the exception; most of the women with whom we spoke went through the abortion process alone.

Going Outside of the System: Abortion Care In-Country

These overarching dynamics—the cost of the procedure, time away from service, perceived lack of confidentiality, and isolation—have shaped some women’s decisions to obtain abortion care in-country, outside of the Peace Corps system.

Christine's Story: Illegal (but Safe) Abortion Care

Christine was serving in the Latin America and Caribbean region in the late 2000s, and became pregnant during her first year of service. Her partner was a host-country national and they decided together that this was not the right time for them to parent. Christine knew the Peace Corps policy with respect to abortion coverage; she knew she would have to return to DC, by herself, pay out-of-pocket, and spend a month in the United States. Christine didn’t want to have the abortion on her own so she asked around. Although abortion was legally permissible only to save the life of the woman in her country of service, women in her community directed her to a private sector doctor in a large city who was reputed to provide safe abortion care. Christine traveled with her partner to the city and paid for the abortion out-of-pocket; the procedure cost nearly 2 months of her stipend. Christine had the illegal abortion without complication and returned to her community within a few days. She was relieved to be able to have the abortion and have her partner—who is now her husband—with her throughout the process. But she resented having to go through this process outside of the Peace Corps system. Indeed, she never told the Peace Corps that she had an abortion in-country because she was afraid that would be grounds for the Peace Corps to terminate her service (interview conducted July 2013).

Of the 18 women who shared their personal abortion experiences with our study team, 5 reported that they had the abortion in-country. We also heard about 9 other in-country abortion experiences from participants who discussed the situation of someone else; in most of these cases the participant had accompanied the volunteer when she obtained an abortion in-country and was able to provide considerable detail about the event. Three of the women who had in-country pregnancy terminations, like Susan, did so through the Peace Corps system either because the abortion took place before the funding ban or because emergency management of the pregnancy was required before medical evacuation for the abortion could take place. However, all of the other cases took place without Peace Corps’ knowledge and varied from legal and safe to illegal and decidedly unsafe. Indeed, we heard about a volunteer who required post-abortion care after suffering complications from an unsafe abortion and another volunteer who experienced long-term medical sequelae. The reasons women decided to have an abortion in-country varied, but in most cases included the cost, timing, confidentiality, and support dynamics that shape the current system of care.

The Abortion Experiences of Rape Survivors: Policy as Punishment

Of the 18 women who described their own personal abortion experiences, 3 became pregnant as a result of rape or sexual violence. In each of these cases the volunteer learned about the funding restrictions on abortion in cases of rape when she found out that she was pregnant.

Michelle's Story: Abortion Care After Sexual Assault

Michelle was in her 20s when she began her Peace Corps service in South Asia in the early 1980s. After being in-country for only a few months she was raped. She was staying in the capital when she learned that she was pregnant; when Michelle told the PCMO that she wanted to terminate the pregnancy she was informed she would be medically evacuated to the United States. Although she had learned about many Peace Corps policies during her preservice training, Michelle did not know that abortion was not covered like all other medical procedures. It was not until she arrived in Hawaii that she learned that she would have to pay for the abortion herself.

Michelle did not have the money to pay for the procedure. Her monthly stipend was approximately $100 and she was told that the abortion would cost nearly 4 times that amount. Michelle had not told her family about the rape; she did not want to tell people in her life why she had returned to the United States and have to explain why she was pregnant. However, Michelle needed to acquire the funds, so she got in touch with a friend from college. Her friend contacted her own parents and they wired money to Michelle. Michelle describes the overall process as humiliating and felt that she was being punished for being raped. Michelle remained in Hawaii for 4 weeks before returning to service. Soon after she returned to her community, she was raped by a different perpetrator, after which she separated from the Peace Corps. Reflecting on her overall experience Michelle stated:

I don’t think abortion is the answer for every Peace Corps volunteer who gets raped; I mean I wouldn’t presume that. I will tell you that it would take someone with, to me, an unimaginable amount of strength to go through with a pregnancy in that situation because even flying over Hawaii I thought, there was a fear I had that the plane was going to set down somewhere and I was going to be stuck being pregnant. With that pregnancy. And I thought I don’t want to spend the rest of my life feeling like I want to claw my skin off my body. And I think that most days I’m a pretty strong person. But all I know is how terrible it was and . . . how scared I was until my friend’s parent’s gave me the money and you know I feel like the federal government has an obligation to revise that sort of standard of care. . . . Why are we penalizing one group of women for choosing their way to serve the world and to serve Peace Corps, you know, our government through Peace Corps? Why are we penalizing them by failing to give them adequate services, in the event that they become raped? I just don’t think that’s fair. I would never say to anyone that yes, you must abort a baby that’s a result of rape, but at the same time I don’t think anyone should be forced to [continue a pregnancy to term] because they don’t have funding (interview conducted June 2013).

As evidenced by Michelle’s experience, many of the dynamics shaping abortion care for Peace Corps volunteers in general also impact those who had an abortion after a sexual assault. But the requirement that a rape survivor pay out-of-pocket for her abortion raised issues regarding disclosure, of the abortion itself and the event that precipitated the need. Michelle’s experience in the 1980s also reflected a different era with respect to the services provided to volunteers after a sexual assault. However, the restrictions on covering abortion care in cases of rape have endured.

In addition to describing the policy as unfair and unjust, survivors of sexual violence who participated in our study also repeatedly described the ban on covering abortion care in cases of rape as punitive and reflective of a broader culture of victim blaming. As one woman who medically separated from the Peace Corps after being raped during her service in Eastern Europe and Central Asia in the late 2000s remarked:

I don’t even know what to say [about the funding ban]. That kind of speaks back to all of the victim-blaming that happens . . . that in a developing country if you are raped, whether it be by someone you know or by a stranger on the street, you were probably doing something wrong. . . . That it’s always the woman’s fault. [The policy is] completely and totally ridiculous.

Participants’ Opinions on Current Abortion Coverage Restrictions

More than two thirds of our participants (68.8%; n = 297) reported that they were not aware of the policy on abortion coverage when they were in service. Not surprisingly, women who had an abortion during their service and those who reported on the abortion experience of a colleague were generally aware of the policy at the time of interview. However, fully half of our participants (50.1%; n = 217) learned about the funding restrictions during the interview itself. Indeed, many of our participants assumed that the coverage restrictions were identical to those for other groups receiving care through federal funding streams, such as Medicaid recipients or federal employees, and believed that abortion was covered for volunteers in cases of life endangerment or when the pregnancy was the result of rape or incest.

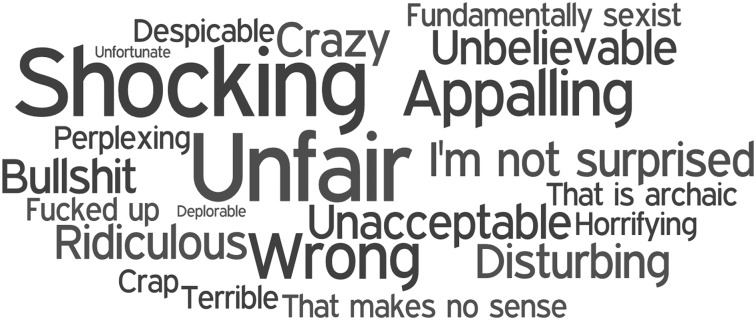

More than 97% of participants (n = 421) disagreed or strongly disagreed with the current “no exceptions” policy. The reactions of both male and female participants to the current funding ban is best characterized as outraged; some of the most common reactions are showcased in the word cloud in Figure 3 that captures language used by participants. When interviewers described the contours of the Peace Corps Equity Act of 2013, a bill that aimed to reconcile abortion coverage for volunteers with other groups who receive federal health benefits, including employees of the Peace Corps,13 97.9% (n = 424) of participants expressed support or strong support for its passage. As a participant stated, “I think it’s absolutely crucial. . . . It seems like a no-brainer.”

FIGURE 3—

Participants’ reactions to the current ban on abortion coverage: documenting the abortion experiences of US Peace Corps Volunteers, June–August 2013.

Note. The size of the word or phrase reflects the relative frequency of the word or phrase in the transcripts.

Participants reported that reconciling abortion coverage for Peace Corps volunteers was important for individual women (and especially rape survivors) as well as symbolically. Many participants expressed the opinion that parity of coverage for volunteers would serve as an important signal that their service was valued.

We are American representatives whether it is at home or abroad . . . and I don’t know why there is some sort of hierarchy, why we are excluded from the policy, but it does feel like we are sort of at the bottom of the totem pole because we are technically volunteers, which is very unfair.

However, more than half of our participants went on to state that covering abortion in cases of life endangerment, rape, or incest would be only a first step and expressed strong support for policies that would treat abortion care as any other health service. As a participant noted,

I think [the Peace Corps Equity Act is] a move in the right direction. I mean . . . [abortion] should be covered if that is the choice of the woman, in any circumstance, if that is what she would prefer. . . . That should be her choice and not just with those caveats.

DISCUSSION

In 1973, the US Supreme Court legalized abortion at the federal level in its landmark Roe v. Wade decision. However, in the wake of Roe a series of federal restrictions were enacted that limited funding for abortion care. Passed by Congress on September 30, 1976, the “Hyde Amendment” to the 1977 Medicaid appropriations bill barred the use of federal funds from covering abortion except in cases of life endangerment.2,14 A year later this restriction was eased and coverage was expanded to include cases in which the pregnancy posed a significant physical health risk or was the result of rape or incest.2 This expansion was fleeting; in 1981 Congressional action again limited abortion care for low-income women to cases of life endangerment. In the 1990s, the funding ban was again eased to include not only life endangerment but also rape or incest.2,15

Although there have been significant fluctuations in the exceptions to Medicaid funding restrictions over the last 38 years, the Hyde Amendment has been renewed in every annual appropriations bill since its enactment.16 The initial passage of the Hyde Amendment also triggered a series of similar restrictions impacting other groups, including federal employees and women in federal prisons; as of the late-1990s, these annual appropriations bills have prohibited the use of federal funds from covering abortion except in cases of life endangerment, rape, or incest.2 In 2013, coverage of abortion for military personnel and their dependents was finally expanded to include not only cases of life endangerment but rape and incest as well.17

Our results call attention to the exceptionality of a policy which restricts abortion coverage for Peace Corps volunteers but not other groups who receive federally funded health care benefits, including employees of the Peace Corps. That rape survivors who choose to terminate a pregnancy are required to pay out-of-pocket is widely perceived by women who have been sexually assaulted and RPCVs in general as unfair and punitive. In recent years, national media has focused on the experiences of women who have been raped during their Peace Corps service and highlighted the need for more comprehensive sexual assault response policies and services.5,18,19 The efforts of advocacy organizations have successfully drawn attention to these issues and prompted reform.20 Lifting the federal restrictions on abortion coverage in cases of rape, whether through the appropriations process or a stand-alone bill, would be consistent with this overarching effort to respond better to the needs of sexual assault survivors serving in the Peace Corps.3,20,21

Our results also showcase the near universal support among RPCVs for reconciling abortion coverage. Extending abortion coverage in cases of life endangerment, rape, or incest would undoubtedly make a difference for the relatively small number of women who meet a narrow eligibility criterion. But reconciliation of the funding restrictions is also symbolically important and would be perceived by most of the RPCVs in our study as an acknowledgment by the federal government that their service is valued. Thus our study strongly supports efforts to lift the “no exceptions” policy on abortion coverage for Peace Corps volunteers.

The impact of policy reform is limited by the extent to which changes are actually implemented. For example, research on the experiences of Medicaid recipients indicates that low-income women often do not receive funded abortion care even when eligible.6,7,22 Lifting the ban is an important first step, but creating mechanisms to ensure that eligible women are able to obtain care will be critical. However, our results indicate that even if the funding ban was eased, most volunteers would still face significant barriers to obtaining affordable, timely, confidential, and supported abortion care. Thus, expanding efforts to inform volunteers about the policy in advance of need, fortifying Peace Corps policies that streamline abortion care for those who are medically evacuated to the United States, linking volunteers who are unable to pay for their abortions with available abortion funds, and identifying mechanisms to increase access to safer abortion care for women while in-country appear warranted. Furthermore, ensuring that Peace Corps volunteers have access to a full range of contraceptive methods, including emergency contraception and long-acting reversible contraceptives such as the intrauterine device and implant is vital. Finally, Susan’s story serves as a reminder that the federal funding restrictions on abortion coverage have not always existed; there have been periods when abortion was covered like all other medical procedures. Although the political realities are such that major reform in federal funding restrictions is currently improbable, ensuring that all women have the right to safe, legal, accessible, and affordable abortion care, without restriction because of reason, remains a priority.

Limitations

Qualitative methods provide an excellent mechanism for in-depth exploration of participants’ experiences, perceptions, and opinions. However, this method is not designed to yield representative and generalizable results. Although we recruited a sizable sample of RPCVs for a qualitative study using diverse recruitment strategies, and we are confident that the themes we identified are significant, we are unable to assess the degree to which these experiences represent broader patterns. Indeed, women who had personal experiences with abortion or sexual violence might have been more likely to participate in our study given the topic of inquiry. Furthermore, the majority of our participants initiated their service in the 2000s and this skew is likely a result of our online recruitment strategies. However, the experiences of RPCVs who served more recently are more likely to reflect current policies, procedures, and practices thus enhancing the overall relevance of the study.

Conclusions

For 35 years, the “no exceptions” policy has required women serving in the US Peace Corps to pay out-of-pocket for abortion care, even in cases of life endangerment, rape, or incest. Extending federal funding for abortion in these narrow circumstances will afford volunteers the same benefits as all other groups who receive health care through the federal government. In addition to making a significant difference in the lives of women who would be eligible for funded care, harmonization of the funding policy sends an important message about the value of those who incur risks and make sacrifices to join the Peace Corps and serve the United States abroad. In May 2014, the Peace Corps Equity Act was reintroduced in the Senate and introduced for the first time in the House.23 Furthermore, in June 2014 the House Appropriations Committee voted to ease the restrictions on abortion coverage for Peace Corps volunteers in the fiscal year 2015 budget.24 Whether through the appropriations process or other legislative efforts, the time has come to lift the funding ban on abortion coverage for Peace Corps volunteers.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant from the HRA Pharma Company’s Foundation and we are extremely grateful for their support. A. M. Foster’s Endowed Chair is funded by the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care in Ontario and we appreciate the general support for her time that made this project possible. This work was supported in part by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant for Infrastructure for Population Research at Princeton University (grant R24HD047879 to J. T.).

This project would not have been possible without a team of dedicated and committed research assistants at the University of Ottawa. We would like to thank Emma Burgess, Esi Dankwa, Julie El-Haddad, Cara Elliott, Maria Fam, Lauren DeGroot, Nour Matar, and Kristina Vogel for their contributions to this project. We are grateful to all of the individuals and organizations that helped us with recruitment for the study. We would like to thank Aram Schvey at the Center for Reproductive Rights and Andi Friedman with the National Partnership for Women & Families for their early feedback and Eddy Niesten, Laryssa Chomiak, Raywat Deonandan, and Cari Sietstra for their advice and support as we completed this project. Finally, we would like to thank all of the returned Peace Corps volunteers who participated in this study and shared their experiences with us.

Note. The conclusions and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organizations with which the authors are affiliated, the individuals and organizations acknowledged in this article, or the funders.

Human Participant Protection

We received ethics approval from the Research Ethics Board at the University of Ottawa (File #H05-13-16).

References

- 1.Corps P. Peace Corps Fact Sheet. Available at: http://files.peacecorps.gov/multimedia/pdf/about/pc_facts.pdf. Published November 21, 2013. Accessed June 20, 2014.

- 2.Boonstra HD. The heart of the matter: public funding of abortion for poor women in the United States. Guttmacher Policy Rev. 2007;10(1):12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rein L. Women’s health groups want Peace Corps volunteers to have insurance coverage for abortions. Washington Post. Available at: http://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/advocates-want-abortion-ban-lifted-for-peace-corps-volunteers/2013/04/25/cb47a420-ada0-11e2-8bf6-e70cb6ae066e_story.html Published April 25, 2013. Accessed June 20, 2014.

- 4. ACLU website Factsheet on Peace Corps abortion coverage. American Civil Liberties Union. Available at: https://www.aclu.org/reproductive-freedom/aclu-factsheet-peace-corps-abortion-coverage. Published April 25 2013. Accessed June 20, 2014.

- 5.Carmon I. Peace Corps volunteer’s hellish abortion story. Salon. Available at: http://www.salon.com/2013/05/02/peace_corps_volunteers_hellish_abortion_story/. Published May 2, 2013. Accessed June 20, 2014.

- 6.Dennis A, Blanchard K. A mystery caller evaluation of Medicaid staff responses about state coverage of abortion care. Womens Health Issues. 2012;22(2):e143–e148. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kacanek D, Dennis A, Miller K, Blanchard K. Medicaid funding for abortion: providers’ experiences with cases involving rape, incest and life endangerment. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2010;42(2):79–86. doi: 10.1363/4207910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones RK, Darroch JE, Henshaw SK. Patterns in the socioeconomic characteristics of women obtaining abortions in 2000-2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2002;34(5):226–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grindlay K, Grossman D. Unintended pregnancy among active-duty women in the United States military, 2008. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(2 pt 1):241–246. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31827c616e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grindlay K, Yanow S, Jelinska K, Gomperts R, Grossman D. Abortion restrictions in the U.S. military: voices from women deployed overseas. Womens Health Issues. 2011;21(4):259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindberg LD. Unintended pregnancy among women in the US military. Contraception. 2011;84(3):249–251. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boonstra HD. Off base: the US Military’s ban on privately funded abortions. Guttmacher Policy Rev. 2010;13(3):6. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Peace Corps Equity Act of 2013, S 813, 113 Cong. 1st Sess (2013).

- 14.Boonstra HD, Sonfield A. Rights without access: revisiting public funding of abortion for poor women. Guttmacher Rep Public Policy. 2000;3(2):8–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fried MG. The economics of abortion access in the US: restrictions on government funding for abortion is the post-Roe battleground. Conscience. 2005-2006;26(4):11–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harper CC, Henderson JT, Darney PD. Abortion in the United States. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:501–512. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montgomery N. Will abortion law change help female troops? Stars and Stripes. February 24, 2013 Available at: http://www.military.com/daily-news/2013/02/25/will-abortion-law-change-help-female-troops.html. Accessed June 20, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stolberg SG. Peace Corps Volunteers Speak Out on Rape. New York Times. May 20, 2011 Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/11/us/11corps.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0. Accessed June 20, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koenen K. Dealing with rape in the Peace Corps. The Boston Globe. May 12, 2011 Available at: http://www.boston.com/bostonglobe/editorial_opinion/oped/articles/2011/05/12/dealing_with_rape_in_the_peace_corps. Accessed June 20, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20. The Kate Puzey Peace Corps Volunteer Protection Act of 2011, 5 USC 5703 (2011)

- 21. Rao A. If military covers abortion after rape, why not the Peace Corps? 2013. Available at: http://www.npr.org/blogs/health/2013/04/29/179267241/if-military-covers-abortion-after-rape-why-not-the-peace-corps. Accessed June 20, 2013.

- 22.Towey S, Poggi S. Abortion Funding: A Matter of Justice. Amherst, MA: National Network of Abortion Funds; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 23. The Editorial Board. Peace Corps Volunteers deserve fairness. The New York Times. June 13, 2014. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/14/opinion/abortions-should-be-covered-by-insurance.html?ref=opinion&_r=1. Accessed June 20, 2014.

- 24.Viebeck E. GOP-led panel approves amendment to expand abortion coverage. The Hill. June 24, 2014 Available at: http://thehill.com/policy/healthcare/210360-gop-led-panel-votes-to-expand-abortion-coverage. Accessed June 25, 2014. [Google Scholar]