Abstract

Objectives. We assessed the impact of a rewards-based incentive program on fruit and vegetable purchases by low-income families.

Methods. We conducted a 4-phase prospective cohort study with randomized intervention and wait-listed control groups in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in December 2010 through October 2011. The intervention provided a rebate of 50% of the dollar amount spent on fresh or frozen fruit and vegetables, reduced to 25% during a tapering phase, then eliminated. Primary outcome measures were number of servings of fruit and of vegetables purchased per week.

Results. Households assigned to the intervention purchased an average of 8 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.5, 16.9) more servings of vegetables and 2.5 (95% CI = 0.3, 9.5) more servings of fruit per week than did control households. In longitudinal price-adjusted analyses, when the incentive was reduced and then discontinued, the amounts purchased were similar to baseline.

Conclusions. Investigation of the financial costs and potential benefits of incentive programs to supermarkets, government agencies, and other stakeholders is needed to identify sustainable interventions.

Health disparities related to poor diets constitute a growing population health concern. Changing diets to improve health outcomes requires a multipronged approach that both encourages responsibility for change and provides the tools to enable change.

We evaluated the effectiveness of a rewards-based incentive program to increase the amounts of fresh and frozen fruit and vegetables purchased by low-income households. Low-income populations purchase and consume smaller amounts of fruit and vegetables than higher-income populations.1,2 We focused on fruit and vegetables because their consumption is strongly associated with the prevention and management of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases.3–7 Indeed, a multicenter randomized trial conducted with persons at high cardiovascular risk recently found that the Mediterranean diet—which includes high intake of fruit and vegetables—reduced the incidence of major cardiovascular events.7

METHODS

A detailed description of the study design, recruitment, and methods is available elsewhere.8 Briefly, the design incorporated a 4-phase prospective cohort study with a randomized intervention. The phases were

1. baseline (≥ 8 weeks; no rewards),

2. intervention (8 weeks; rewards = 50% of produce spending),

3. tapering (4 weeks; rewards = 25% of produce spending), and

4. follow-up (6 weeks; no rewards).

The primary outcomes were the number of servings of fresh and frozen fruit and of fresh and frozen vegetables purchased per week. We hypothesized that households receiving the intervention would purchase more fruit and more vegetables than the control households (who were wait listed for the intervention). In within-group comparisons over time, we expected that the weekly purchase of fruit and vegetables would be greater than baseline in each of the intervention, tapering, and follow-up phases.

We collected data from December 2010 through October 2011. We enrolled participants in 3 recruitment waves. We retrieved baseline purchase data (from participants’ registered supermarket loyalty cards) for all waves back to the fixed date of December 1, 2010. Data analysis took place from October 2011 through April 2013.

Setting and Participants

The study supermarket operated in a census tract in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, with a racial composition of 89.1% African American, 6.6% White, and 4.3% other. Hispanics of any race made up 3% of that population.9 Most of the store shoppers resided in the area.

Adults who self-identified as the primary grocery shopper for the household, had at least 1 child in the home full time, and had a household income of $60 000 or less were eligible for the study. Additional inclusion criteria were a minimum 8-week history of shopping at the study store, shopping there at least 3 times a month, buying at least half of their household groceries there, and buying half or more of their fresh and frozen produce there. Participants were also required to have a registered loyalty card for the study supermarket to track purchases. We conducted initial screening for eligibility either in person at the market or by telephone. Subsequently, we verified 8-week shopping history by comparing transactions against participants’ loyalty card numbers. To obtain additional individual and household information, we interviewed eligible shoppers who had provided informed consent. The collection of race and ethnicity was consistent with the standards used in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.10 Participants could self-identify by race or ethnicity or both and with more than 1 race.

We randomly assigned participants to 1 of the 2 treatment groups (intervention or wait-listed control) with a computer program. The research coordinator and research assistant notified participants of their study group and start date by telephone. We reached the majority by telephone and left voice messages for those we were unable to reach after several attempts.

Intervention Components

We used gift cards for the study supermarket to provide the incentives to participants. We sent these cards to participants at the beginning of the study without any dollar amount added.

During the (full active) intervention phase, study shoppers received a rebate of 50% of the dollar amount they spent on fresh or frozen produce. In the tapering phase, the amount fell to 25%. During the follow-up phase, we offered no price incentive. We added earned rewards to the store gift card at 2-week intervals. We also sent study households a total of 4 study-specific newsletters containing nutritional information and recipes involving fruit and vegetables. During phases 2 and 3, we included written reports of their produce purchases and the dollar amount accrued on the gift card with the newsletters.

One week before starting the intervention phase, we sent participants a mailing with study materials:

Two plastic magnetic stripe cards: 1 store loyalty card (branded for the study), with instructions for use, and 1 store gift card (without any dollar amount added);

A study calendar with the relevant dates of each phase;

A user-friendly explanation about how the rewards worked in each phase;

A study newsletter; and

The name and phone number to call for questions about the study.

Data Collection

The supermarket data analyst sent the point-of-sale purchase data to the study’s data manager. A researcher-written computer program extracted purchase information related to fruit and vegetables from the point-of-sale data. Participants’ loyalty card numbers served as unique identifiers to relate purchases to individual study households.

We calculated adult servings of fruit and vegetables according to the Food and Drug Administration's Food Buying Guide for Child Nutrition Programs.11 To derive the number of adult servings, we multiplied the number of child-size servings by the standard portion size of the specific produce item.12,13 In about 10% of recorded produce purchases, the specific type of fruit or vegetable was not identifiable. To avoid underestimating the purchase of produce, we approximated the number of servings for these unclassified items (Appendix A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Participants completed 2 surveys; 1 at the time of enrollment and 1 during follow-up. We collected survey data on paper forms, and the research coordinator manually entered the data into the database.

Statistical Analysis

We compared the average number of servings of fruit and vegetables purchased in the intervention and control groups over the same 8-week period with an as-randomized (intention to treat) analysis. We used a t test with unequal variances and bootstrap resampling to compare means of the household-level average purchases in the 2 groups.

Price has been recognized as a key driver in food-purchasing decisions, particularly for fruit and vegetables.14 We controlled statistically for changing weekly prices of fruit and of vegetables with a chained Fisher price index. In price-adjusted analyses, we used generalized linear models with a log link and Gaussian distribution to compare the average number of servings purchased per week in the intervention and control groups.15

In all of the longitudinal analyses (comparing produce purchases between study phases), households served as their own controls. These analyses also used separate models for fruit and for vegetable purchases. We used bivariate analysis (paired t test), without adjustment for weekly changes in price, to compare produce servings purchased in the baseline phase to each of the subsequent phases. To provide robust analyses with minimal assumptions, we derived 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the paired differences from bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrap resampling. We included participants who had shopping data during the phase of comparison and the baseline in these household-level analyses.

We used 2-part statistical models that were price adjusted to make 2 distinct types of comparisons.16 We compared the probability of any produce purchase in a week (from all observations) and the amount purchased (limited to when produce was purchased). In the first part, we estimated changes in the probability of some produce purchase in a week in the baseline phase to a week in each subsequent phase. We used price-adjusted fixed-effects (within household) generalized linear models with a log link and a binomial distribution.

In the second part, we compared the amounts of produce purchased per week in the intervention, tapering, and follow-up phases to baseline. We controlled for changing weekly produce prices with fixed-effects generalized linear models with a log link, Gaussian distribution, and bias-corrected bootstrap 95% CIs. When households did not purchase any produce during a given week, we excluded data from that week from this analysis regardless of whether they bought nonproduce items.

To provide stable estimates, all bootstrap analyses incorporated 1000 resamples. We exponentiated estimates from models with log links back to their original scale. All statistical tests were 2 sided. A 95% CI that included zero indicated a lack of statistical significance (P > .05). We performed statistical analyses with Stata version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX), SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and PASW version 18.0 (PASW, Inc, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

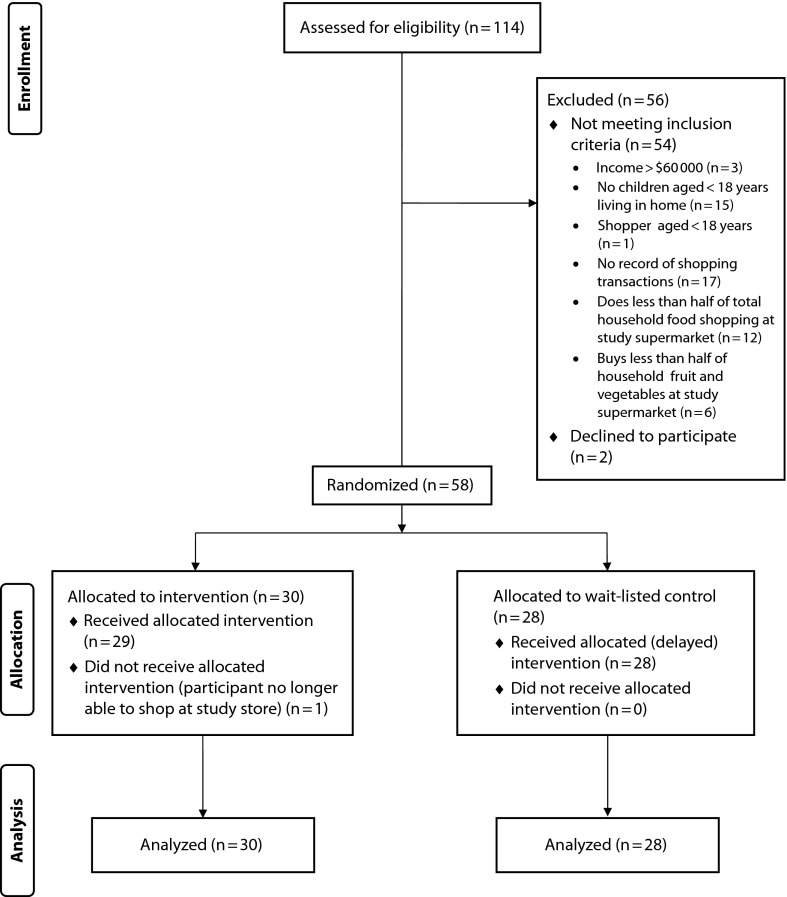

Randomization resulted in assignment of 52% (n = 30) of participants to the intervention group and 48% (n = 28) to the wait-listed control group. Participant flow from eligibility through random assignment and analysis is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1—

Flow of participants through trial of incentives for purchase of fruit and vegetables among low-income households: Rewards Study; Philadelphia, PA; 2010–2011.

Participants

The majority of participants were African American (95%) and women (81%; Table 1). The average age of the primary shopper was 50.4 years. The average household size was 3.8 persons, with an average of 1.7 children living in the household. Annual income was $25 000 or less in 69% of households (eligibility was up to $60 000). Sixty-two percent of participants were enrolled in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and 29% in the Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC).

TABLE 1—

Baseline Characteristics of Randomized Participants Overall and by Treatment Arm in Trial of Incentives for Purchase of Fruit and Vegetables Among Low-Income Households: Rewards Study; Philadelphia, PA; 2010–2011

| Variable | All Participants (n = 58), No. (%) or Mean ±SD | Intervention Group (n = 30), No. (%) or Mean ±SD | Wait-listed Control Group (n = 28), No. (%) or Mean ±SD |

| Household size | 3.8 ±1.4 | 3.7 ±1.3 | 3.9 ±1.5 |

| Children in household | 1.7 ±1.0 | 1.5 ±0.7 | 1.9 ±1.3 |

| Age, y | 50.4 ±13.2 | 53.4 ±13.0 | 47.1 ±12.7 |

| Women | 47 (81.0) | 26 (86.7) | 21 (75.0) |

| African American | 55 (94.8) | 29 (96.7) | 26 (92.9) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married/cohabitating | 20 (34.5) | 9 (30.0) | 11 (39.2) |

| Single/never married | 18 (31.0) | 10 (33.3) | 8 (28.6) |

| Divorced/separated | 11 (19.0) | 4 (13.3) | 7 (25.0) |

| Widowed | 9 (15.5) | 7 (23.4) | 2 (7.2) |

| Education, y | |||

| ≤ 12 | 28 (48.3) | 16 (53.3) | 12 (42.9) |

| > 12 | 30 (51.7) | 14 (46.7) | 16 (57.1) |

| Household income ≤ $25 000 | 40 (69.0) | 21 (70.0) | 19 (67.9) |

| SNAP enrolled | 36 (62.1) | 20 (66.7) | 16 (57.1) |

| WIC enrolled | 17 (29.3) | 5 (16.7) | 12 (42.9) |

Note. SNAP = Supplemental Nutrition Education Program; WIC = Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Household and shopper characteristics were similar in the 2 study groups, with the exception that more control than intervention participants were enrolled in WIC (43% vs 17%). Most participants (95%) lived within 2 miles of the study supermarket.

Randomized Comparisons

Fruit and vegetables combined.

In a bivariate analysis (as randomized), control households purchased an average 6.4 servings of fruit and vegetables (combined) per week. Intervention households purchased 16.7 servings per week, or 10.4 (95% CI = 4.8, 17.8; P < .002) more servings than control households. After adjustment for weekly changes in produce prices, the difference between average purchases in intervention and control households was 10.2 servings (95% CI = 3.6, 25.7; P < .001).

In a previous pilot study that used a coupon-based financial incentive to promote purchase of fresh fruit and vegetables, we found that vegetable purchases increased more than did fruit purchases.17 For this reason, we present most results for fruit and vegetables purchases separately.

Vegetable purchases.

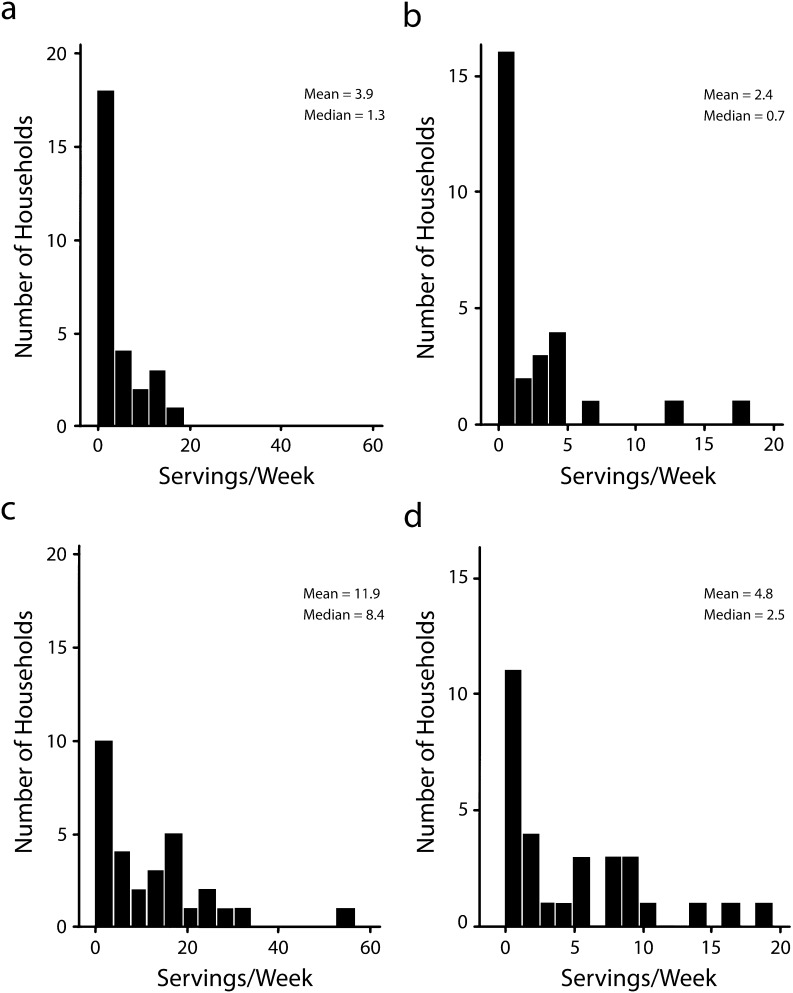

Only half of the control households purchased more than 1.3 servings of vegetables per week (Figure 2). By contrast, half of the intervention households purchased more than 8.4 servings of vegetables per week; the median number of vegetable servings purchased by the intervention group was more than 6 times that of the control group.

FIGURE 2—

Distribution of average numbers of purchased servings per week in low-income households of (a) vegetables in the control group, (b) fruit in the control group, (c) vegetables in the intervention group, and (d) fruit in the intervention group: Rewards Study; Philadelphia, PA; 2010–2011.

In an as-randomized (intention to treat) analysis, on average, intervention households purchased 8 (95% CI = 4.1, 13.4; P < .002) more vegetable servings than did control households. With adjustment for weekly changes in vegetable prices, this increase remained (8 more servings; 95% CI = 1.5, 16.9; P < .001).

Fruit purchases.

About half of control households purchased little or no fruit in an average week. Half of the intervention households purchased more than 2.5 servings per week; the median weekly number of fruit servings purchased by the intervention group was more than 3 times that of control households (Figure 2).

In an as-randomized analysis, on average, intervention households purchased 2.4 (95% CI = −0.2, 4.6; P = .06) more fruit servings per week than did control households. However, in a price-adjusted, as-randomized analysis, the difference was 2.5 servings (95% CI = 0.3, 9.5; P = .01).

Study households that received a 50% rebate (intervention group) purchased both more vegetables and more fruit than did control households in price-adjusted randomized comparisons.

Longitudinal Analyses

Longitudinal analyses examined purchasing practices within households, comparing their weekly purchases of fruit and vegetables at baseline to each of the subsequent study phases.

We compared both the percentage of weeks in which any produce was purchased and changes in the average number of servings bought. Because we compared the intervention and control groups in the randomized comparisons, we compared household produce purchases in phase 3 (tapering) and phase 4 (follow-up) with phase 1 (baseline).

Vegetable purchases over time.

In price-adjusted analyses, both the number of weeks in which households bought vegetables during phase 3 and the average number of vegetable servings purchased during that phase were essentially unchanged from phase 1. Vegetable purchases were also similar in phases 1 and 4 (Table 2). Bivariate analyses found similarly small increases in household averages for the amount of vegetables purchased in phases 3 and 4 from baseline (both, P ≥ .11).

TABLE 2—

Price-Adjusted Within-Household Comparisons of the Probability and the Amounts of Vegetables and Fruit Purchased in Baseline and Other Study Phases: Rewards Study; Philadelphia, PA; 2010–2011

| Variable | Phase 1, Baseline, % or No. | Phase 2, Intervention, % or No. | Difference Between Phases 1 and 2, Mean (95% CI) | P | Phase 3, Tapering, % or No. | Difference Between Phases 1 and 3, Mean (95% CI) | P | Phase 4, Follow-up, % or No. | Difference Between Phases 1 and 4, Mean (95% CI) | P |

| Vegetables | ||||||||||

| Probability of purchasea | 24.6 | 32.9 | 33.9 (10.6, 62.0) | .003 | 26.1 | 6.2 (−17.2, 36.2) | .64 | 29.5 | 20.2 (−4.3, 50.9) | .11 |

| Amount purchased,b servings/wk | 21.0 | 27.3 | 6.3 (1.7, 13.9) | .006 | 20.9 | −0.1 (−5.1, 8.0) | .99 | 22.2 | 1.2 (−3.8, 6.3) | .7 |

| Fruit | ||||||||||

| Probability of purchasea | 17.8 | 28.5 | 60.4 (15.9, 122.0) | .004 | 27.1 | 52.9 (10.8, 111.2) | .01 | 23.0 | 29.3 (−9.9, 85.5) | .16 |

| Amount purchased,b servings/wk | 12.0 | 15.0 | 3.0 (−0.2, 6.7) | .053 | 13.1 | 1.1 (−2.0, 6.2) | .53 | 11.5 | −0.5 (−5.2, 3.7) | .99 |

Note. CI = confidence interval. Estimates of servings were derived from the Department of Agriculture's Food Buying Guide for Child Nutrition Programs11 and were standardized according to portion sizes in the Food Guide Pyramid.12,13 All 95% CIs are bias corrected and derived from 1000 bootstrap resamples.

Analyses of the percentage of weeks in which the produce was purchased incorporated 2087 weekly observations in 58 households.

Analyses of weekly number of servings purchased incorporated 564 observations in 56 households for vegetable purchases and 458 weekly observations in 58 households for fruit purchases.

Fruit purchases over time.

In price-adjusted analyses, the percentage of weeks in which households purchased fruit increased substantially from phase 1 to phase 3. During phase 1, households purchased fruit in only about 17.8% of weeks (Table 2). During phase 3, households purchased fruit in 27.1% of weeks, for an increase from phase 1 of 52.9% (95% CI = 10.8%, 111.2%; P = .01). However, in weeks when households made these fruit purchases, on average, they purchased a similar amount as at baseline (P = .53). In a bivariate analysis, households purchased 2.5 (95% CI = 0.1, 4.6; P = .04) more servings in phase 3 than in phase 1.

During phase 4, changes in the percentage of weeks in which households purchased fruit and the amount purchased were not statistically discernable from baseline (P ≥ .16). This result was similar to the findings of a bivariate analysis comparing household averages of the amount of fruit purchased in phase 4 and at baseline (P = .13).

Participant Feedback

We conducted a follow-up survey to elicit participant experience with the study. Fifty participants completed the survey (35 via telephone, 15 returned by mail; response rate = 88%). We asked participants whether their purchasing of fruit and vegetables was affected “as a result of being in the study.” Sixty-two percent said they bought fruit and vegetables “that were more nutritious,” 50% bought “more fruit and vegetables [than they usually did],” 40% bought fruit and vegetables “that were not usually available in their household,” and 34% bought fruit and vegetables “that were new to them.”

Most (80%) reported that it was not at all difficult to participate in the study. Subsequently, when asked specifically if they had any problems with the study, 26% identified a problem. The following problems were identified: forgetting to bring or swipe their study loyalty card, feeling that produce in the store was overpriced, encountering supermarket staff who were not knowledgeable about the study, having transportation problems getting to the store, having personal financial constraints that limited their shopping, and having to deal with an event in their personal life that made it more difficult for them to actively participate.

DISCUSSION

We tested a rewards-based incentive program for promoting purchase of fresh and frozen fruit and vegetables in a low-income community. We analyzed more than 2100 store transactions by 58 low-income households over a period of more than 30 weeks, with minimal missing data. In addition, our follow-up survey had a high response rate.

Half of the control households purchased fewer than 1.3 servings of vegetables and virtually no fruit per week. Regrettably, it appears that the low-income households in our sample typically purchase very little produce.

In randomized comparisons, average weekly purchases of vegetables were 3 times as high and of fruit were twice as high in the intervention as in the control group. The price-adjusted results supported our expectation that households receiving the 50% price incentive would buy more fruit and more vegetables than control households. Although the groups were not balanced in WIC enrollment, WIC was not associated with the amount of produce purchased and thus not a confounder.

Our multifaceted approach to analyzing the complex study data was an important strength of our study. Comparing household-level averages in the 2 study groups in as-randomized analyses provided an easy-to-understand evaluation of the intervention. Although that analysis required few statistical assumptions, it used the household averages (not the weekly averages) in the group comparisons and did not control for price changes. We recognized changing store prices of fruit and vegetables as a plausible threat to internal validity.18 To address these issues, we controlled for price changes in our analyses of weekly data. However, that involved using more complex 2-part models that required multiple statistical assumptions. These 2 disparate approaches to the randomized comparison of intervention and control groups yielded similar results, lending us confidence in our conclusions.

In the within-household analyses, households served as their own controls, so that all fixed characteristics of participants and their households (both measured and unmeasured) were controlled.19 During the tapering and follow-up phases, the amounts of fruit and of vegetables purchased were not statistically discernible from baseline. Thus, it appears that although a price incentive of 50% of dollars spent on fresh and frozen produce increased purchase of those foods, a price incentive of 25% did not. It is possible that the increase in purchases from the baseline to the intervention period was not retained in the tapering period because of a history effect. That is, after having received a 50% incentive, the lower 25% amount may have actually served as a disincentive. Another possible explanation is that the novelty of the incentive may have worn off by the time of the tapering period.

The probability that participants would buy produce provides an additional perspective to that offered by examining only changes in the amount purchased. In longitudinal analyses, households continued to purchase some fruit in a higher percentage of weeks in the tapering phase than at baseline. These results suggest a possible impact of the rewards program on encouraging purchasing behavior, although this requires further investigation.

Methods used by other researchers to quantify food purchases have included the collection of grocery receipts and self report.20–28 The collection of consumer purchases at point of purchase as we and others have done29–31 overcomes some of the vulnerabilities of the collection process and improves estimation of purchases from the specific study site. Nonetheless, we caution other investigators that procedures for using consumer loyalty card data for research are complex and time consuming. Translating data from loyalty cards required sophisticated computer programming and a strong collaborative relationship with the supermarket data analyst.

A limitation of our study was that the total amount of produce purchased by study households may have been underestimated. Although participants reported doing most of their grocery shopping at the study supermarket and buying most of their produce there, they identified other sources of produce in pre- and poststudy surveys. In addition, participants may not have used their loyalty cards for every purchase. However, the primary comparisons addressed differences between randomly assigned groups, thus excluding underestimation of produce purchases as an alternative explanation. Underestimation of produce purchases could have confounded the longitudinal comparisons only if the degree of underestimation varied by phase.

Our findings suggest that providing a sufficient level of financial incentive can increase fruit- and vegetable-purchasing behaviors. We recognize that wider application of financial incentives to promote healthier eating would be expensive. Investigation of the financial costs and potential benefits of such programs to supermarkets, food suppliers and manufacturers, government agencies, and other stakeholders is needed to identify sustainable interventions.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation through its Healthy Eating Research program (grant 68246).

We thank Fresh Grocer staff Carly Spross and Glenn Foster for their valuable assistance in this study. We gratefully acknowledge Jeph Herrin, PhD, for his consultation on the use of statistical models. We thank the reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions.

Human Participant Protection

The institutional review board at Einstein Healthcare Network approved this study.

References

- 1.Stewart H, Harris JM. Obstacles to overcome in promoting dietary variety: the case of vegetables. Appl Econ Perspect Policy. 2005;27(1):21–36. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blisard N, Stewart H, Jolliffe D. Low-Income Households’ Expenditures on Fruits and Vegetables. Washington, DC: US Dept of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu S, Serdula M, Janket SJ et al. A prospective study of fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(12):2993–2996. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.12.2993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joshipura KJ, Hu FB, Manson JE et al. The effect of fruit and vegetable intake on risk for coronary heart disease. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(12):1106–1114. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-12-200106190-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu S, Manson JE, Lee IM et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: the Women’s Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72(4):922–928. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.4.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He K, Hu FB, Colditz GA, Manson JE, Willett WC, Liu S. Changes in intake of fruits and vegetables in relation to risk of obesity and weight gain among middle-aged women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28(12):1569–1574. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvado J et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(14):1279–1290. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phipps EJ, Wallace SL, Stites SD et al. Using rewards-based incentives to increase purchase of fruit and vegetables in lower-income households: design and start-up of a randomized trial. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(5):936–941. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012004934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. US Census Bureau. Census interactive population search. 2010. Available at: http://www.census.gov/2010census/popmap/index.php. Accessed May 13, 2013.

- 10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm. Accessed May 13, 2013.

- 11. US Dept of Agriculture. Food buying guide for child nutrition programs. Available at: http://www.fns.usda.gov/tn/resources/FBG_Index.pdf. Accessed April 24, 2013.

- 12. US Dept of Agriculture. What counts as a cup of vegetables? Available at: http://www.choosemyplate.gov/food-groups/vegetables_counts_table.html. Accessed April 24, 2013.

- 13. US Dept of Agriculture. What counts as a cup of fruit? Available at: http://www.choosemyplate.gov/food-groups/fruits_counts_table.html. Accessed April 24, 2013.

- 14.Blakely T, Ni Mhurchu C, Jiang Y et al. Do effects of price discounts and nutrition education on food purchases vary by ethnicity, income and education? Results from a randomised, controlled trial. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65(10):902–908. doi: 10.1136/jech.2010.118588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forsyth FG, Fowler RF. The theory and practice of chain price index numbers. J R Stat Soc Ser A. 1981;144(2):224–246. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cameron AC, Trivedi PK. Microeconometrics Using Stata. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phipps EJ, Braitman LE, Stites SD, Wallace SL, Singletary SB, Hunt LH. The use of financial incentives to increase fresh fruit and vegetable purchases in lower-income households: results of a pilot study. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(2):864–874. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shadish W, Cook T, Campbell D. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allison P. Fixed Effects Regression Models. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waterlander WE, de Boer MR, Schuit AJ, Seidell JC, Steenhuis IH. Price discounts significantly enhance fruit and vegetable purchases when combined with nutrition education: a randomized controlled supermarket trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97(4):886–895. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.041632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cullen K, Baranowski T, Watson K et al. Food category purchases vary by household education and race/ethnicity: results from grocery receipts. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(10):1747–1752. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mankoff J, Hsieh G, Hung HC, Lee S, Nitao E. Using low-cost sensing to support nutritional awareness. Paper presented at: 4th International Conference on Ubiquitous Computing; September 29, 2002; Göteborg, Sweden.

- 23.Martin SL, Howell T, Duan Y, Walters M. The feasibility and utility of grocery receipt analyses for dietary assessment. Nutr J. 2006;5:10. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-5-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.French SA, Wall M, Mitchell NR. Household income differences in food sources and food items purchased. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:77. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ransley JK, Donnelly JK, Khara TN et al. The use of supermarket till receipts to determine the fat and energy intake in a UK population. Public Health Nutr. 2001;4(6):1279–1286. doi: 10.1079/phn2001171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rankin JW, Winett RA, Anderson ES et al. Food purchase patterns at the supermarket and their relationship to family characteristics. J Nutr Educ. 1998;30(2):81–88. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson JV, Bybee DI, Brown RM et al. 5 a day fruit and vegetable intervention improves consumption in a low income population. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101(2):195–202. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(01)00052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herman DR, Harrison GG, Afifi AA, Jenks E. Effect of a targeted subsidy on intake of fruits and vegetables among low-income women in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(1):98–105. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.079418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ni Mhurchu C, Blakely T, Wall J, Rodgers A, Jiang Y, Wilton J. Strategies to promote healthier food purchases: a pilot supermarket intervention study. Public Health Nutr. 2007;10(6):608–615. doi: 10.1017/S136898000735249X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eyles H, Jiang Y, Ni Mhurchu C. Use of household supermarket sales data to estimate nutrient intakes: a comparison with repeat 24-hour dietary recalls. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(1):106–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamilton S, Ni Mhurchu C, Priest P. Food and nutrient availability in New Zealand: an analysis of supermarket sales data. Public Health Nutr. 2007;10(12):1448–1455. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007000134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]