Abstract

Objective

The short-term benefits of exercise for persons with Parkinson Disease (PD) are well-established, but long-term adherence is limited. The aim of this study was to explore the feasibility, acceptability and preliminary evidence of effectiveness of a virtual exercise coach to promote daily walking in community dwelling persons with PD.

Design

Twenty subjects with PD participated in this Phase I single group, non-randomized clinical trial. Subjects were instructed to interact with the virtual exercise coach for 5 minutes, wear a pedometer and walk daily for one month. Retention rate, satisfaction and interaction history were assessed at 1-month. Six-minute walk and gait speed were assessed at baseline and post intervention.

Results

Participants were 55% female, mean age 65.6. At study completion, there was a 100% retention rate. Subjects had an average satisfaction score of 5.6/7 (with seven indicating maximal satisfaction) with the virtual exercise coach. Interaction history revealed that participants logged-in an average of 25.4 days (SD 7) out of the recommended 30 days. Mean adherence to daily walking was 85%. Both gait speed and the 6-minute walk test significantly improved (p<0.05). No adverse events were reported.

Conclusions

Sedentary persons with PD successfully used a computer and interacted with a virtual exercise coach. Retention, satisfaction and adherence to daily walking were high over one-month and significant improvements were seen in mobility.

Keywords: Parkinson Disease, Exercise, Virtual Systems, Adherence

Over the last decade, evidence has emerged that there are significant and clinically meaningful benefits of short-term exercise for persons with PD.1, 2 A recent Cochrane review identified 33 randomized controlled trials (RCT’s) with 1518 participants examining the benefits of physical therapy compared to no-intervention in persons with PD.3 Results revealed significant improvements in gait velocity, functional mobility, balance and activities of daily living following physical therapy compared to no intervention. Exercise studies of both rodent and primate models of PD demonstrate increased survival of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons suggesting a potential disease modifying effect of exercise.4, 5 These studies highlight the importance of exercise across many levels – improving quality of life, improving function (walking and balance), reducing impairments (strength and cardiovascular fitness) and potentially acting as a disease modifying agent. Exercise is increasingly being recognized as a critical component of the management of Parkinson Disease and should be adopted by all patients diagnosed with this disease.6

Many exercise interventions described in the literature have been structured programs implemented in a clinical facility under direct supervision of a physical therapist or other health care professional. Most have reported benefits over the short-term (4–12 week); however, many studies revealed that once the sessions were completed and instruction or supervision were no longer provided, participants failed to adhere to the exercise program and subsequently experienced a detraining effect – losing the gains initially made.1 The longest duration of any exercise program included in the recent Cochrane review of exercise and PD was 24 weeks.3 Limited adherence to long term exercise in the community thereby diminishes the potential impact of exercise on reducing disability.

Although persons with PD may have more difficulty exercising as the disease progresses, previous work reveals that personal factors, such as low self-efficacy and poor outcome expectation were stronger predictors of exercise adherence than disease severity.7 In addition, social support has been shown to strongly influence health promoting behaviors.8, 9 Successful methods to improve exercise adherence over the long-term must address these personal and social factors.

Relational agents provide a promising mechanism to increase physical activity in older adults with chronic disabilities. Relational agents are computational artifacts designed to establish long-term social-emotional relationships with users such as therapeutic alliance relationships in automated health behavior change interventions.10, 11 In this work, the relational agent takes the form of an animated character that simulates face-to-face conversation with users – promoting relationship building crucial to facilitating behavioral change. Users “talk” to the character using touch screen input on a tablet computer in their homes. Relational agents can play the role of a virtual exercise coach (designed using custom software developed by the authors using a non-commercial research software framework).10, 11 Daily counseling sessions are designed to establish a social bond with users and improve motivation, self-efficacy and outcome expectation. The virtual coach promotes self-efficacy and outcomes expectations by problem solving (helping users overcome barriers to exercise); positive reinforcement when goals are met; encouragement when goals are not met; negotiating short- and long-term goals (so that goals are realistic and achievable); through explicit expression of confidence (“I know you can do it.”; “We make a great team.”; etc.) and by reminding users of past successes via the self-monitoring charts. These coaches have been successfully used in randomized controlled trials to provide theoretically-based daily counseling which has resulted in increased daily walking in healthy adults, older adults and people who are obese.12–15 Strategies from behavioral change and cognitive behavioral theory, including: goal setting, shaping, positive feedback, self-monitoring, overcoming obstacles (“problem solving”), and education are integrated into the dialogue to promote an increase in physical activity.

Virtual exercise coaches have not been evaluated for use by people with any debilitating chronic conditions or any neurological disorders. Initial feasibility (i.e., acceptability and usability) of using a virtual exercise coach needs to be explored in persons with PD prior to assessing evidence of efficacy in promoting long-term adherence to exercise.

In this trial, the virtual exercise coach focused on promoting walking in persons with PD as a form of exercise. Rather than implementing a particular discrete exercise program at a particular frequency and duration, the emphasis was on exercising by increasing walking as a part of one’s daily routine. Walking is an appealing form of exercise in that it is intended to be carried out very long term, is an activity that everyone is familiar with and can be performed at home or local community. This reduces potential barriers such as the need to travel to a specific location or to use specialized equipment. Walking is also an important determinant of disability and quality of life in people with PD and effective interventions focused on improving walking are essential.16, 17 In a study investigating the evolution of disability in PD, Shulman identified impairments in walking as precipitating the onset of disability, a “clinical red flag” highlighting the need for more effective treatments of gait dysfunction to improve mobility and delay disability in PD.18 A recent longitudinal study of persons with PD revealed a significant decrease (12%) in number of steps (effect size = 0.28) from baseline to one year indicative of a decrease in physical activity over the course of a year and the need to focus on improving walking in this population.19 Exercise trials that have emphasized walking in persons with PD reveal improvements in walking speed and step length (Herman 2009 review paper treadmill, Rescue trial 2007) suggesting the potential benefits of increasing walking as a form of exercise.20, 21

The purpose of this study was to conduct a Phase I clinical trial to evaluate the acceptability, usability and safety of a virtual exercise coach in promoting daily walking in community dwelling persons with PD over a one month period. In addition, preliminary evidence of efficacy of the virtual coach on changes in mobility outcomes over a one month period was investigated. We hypothesized that it would be feasible for persons with PD to interact with the virtual exercise coach in their home environments and adhere to a daily walking program in a safe manner.

METHODS

Subjects

Twenty people with PD were recruited from the Center for Neurorehabilitation at Boston University and The Parkinson Disease and Movement Disorders Center at Boston Medical Center. Subjects were included in the trial if they had a diagnosis of idiopathic PD using the UK Brain Bank Criteria with a Hoehn & Yahr (H&Y) score of 1.5, 2, 2.5 or 3.22, 23 Persons were excluded if they had a diagnosis of atypical Parkinsonism, a significant cognitive impairment (i.e. Mini-Mental State Exam score of <24)24; cardiac problems that interfere with ability to safely exercise (uncontrolled CHF, uncontrolled arrhythmias, unstable angina, MI in the past 6 months, cardiomyopathy, uncontrolled elevated blood pressure);25, 26 musculoskeletal disorders of the lower extremities that may interfere with long-distance walking; visual or hearing impairment that would make it impossible for the participant to interact with the virtual coach; not fluent in conversational English; or unable to walk 100 meters without a gait device.

Design

This study was a phase I clinical trial using a single-group nonrandomized design. During an initial clinic visit at the Center for Neurorehabilitation at Boston University, potential subjects who agreed to participate in the study provided informed consent and were screened for eligibility. Those meeting inclusion criteria participated in a baseline assessment session. Following the baseline assessment, subjects were instructed in how to use the pedometer and interact with the virtual exercise coach. All subjects participated in a one month intervention program at home, with recommended daily wearing of a pedometer and daily conversations with the virtual coach and a final assessment session post intervention. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Boston University.

Measures

Characterizing the Population

Data collected during the baseline assessment included sociodemographics, measures of disease severity23, 27 and exercise stage of change.28 The gold standard measures of disease severity included both the Hoehn & Yahr stage and the Movement Disorders Society Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) (REF).23, 27 The exercise stages of change included: Precontemplation, not intending to exercise regularly in the next six months; Contemplation, intending to begin exercising regularly in the next six months; Preparation, intending to begin exercising regularly in the next thirty days; Action, exercising regularly for less than six months; and Maintenance, exercising regularly for at least six months.28

Usability and acceptance of the virtual exercise coach were evaluated as a means of assessing feasibility. First, to assess usability, the Interaction History was recorded in log files that kept track of all actions participants took with their tablet computers. The number of days each subject logged into the computer to interact with the virtual coach was assessed. Second, a series of single-item scale measure questions that have been used in previous studies were used to evaluate acceptance.11, 14, 29 These questions were used to rate satisfaction with the virtual coach, desire to continue using the system and likability of the virtual coach character. All items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7). In addition, the number of steps walked each day was measured using Omron HJ- 720ITC pedometers (http://www.omronhealthcare.com/products/hj-720itc/) which recorded steps throughout the 30-day intervention. Steps data was electronically uploaded from a digital pedometer directly to a tablet computer via a USB cable. Subjects also recorded their steps daily on paper log sheets in the event the electronic data files were lost or inaccessible.

Safety

Adverse events were monitored with phone calls at 48 hours post baseline assessment, at 2 weeks and at the end of the one month intervention period. Standardized questions were asked about any new falls, illnesses, injuries, and use of any health care services.

Efficacy

Preliminary evidence of efficacy was measured using physical mobility tests related to walking at baseline and at the end of the intervention. The 6-minute walk test (6MWT) was used to measure the distance participants could walk in 6 minutes. Participants were instructed to “cover as much ground as possible.” Validity and high test-retest reliability have been demonstrated for the 6MWT in patients with cardiopulmonary disease and in patients with neurological diseases, including those with PD.30, 31 Self-selected and maximal pace gait speed were measured during a 10 meter walk. Two trials at each pace were recorded, with the average speed at each pace used as separate dependent variables. Gait speed provides a standardized measure of gait function that has been found to be reliable and is sensitive to change over a broad range of physical function in elderly individuals and persons with neurologic pathology.32

Intervention

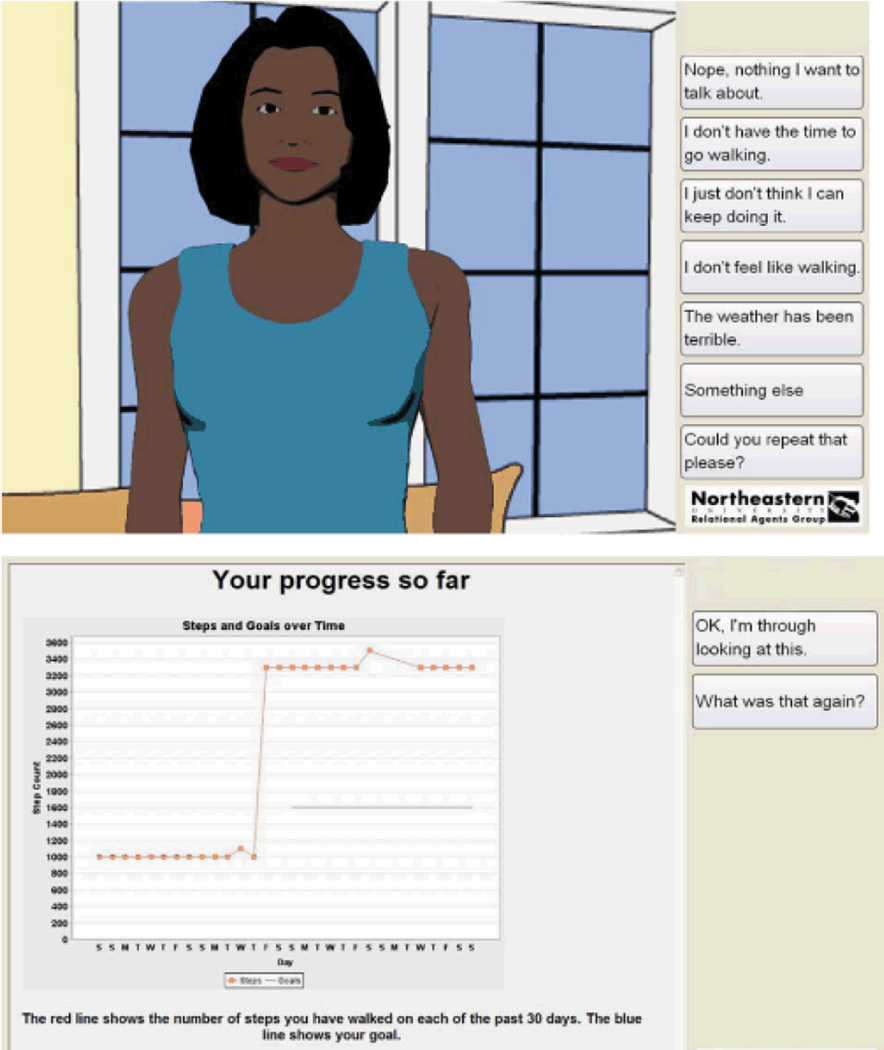

The intervention was designed to increase physical activity by promoting additional daily walking using a pedometer and brief daily interactions with the computer animated virtual exercise coach. Subjects were instructed to wear a pedometer and walk daily for one month and to interact with the virtual exercise coach (Figure 1) for 5 minutes per day. Conversations with the virtual exercise coach were comprised of dialogue and other media designed to promote health behavior change and dialogue and conversational nonverbal behavior designed build a relationship and therapeutic alliance with the participant (Table 1).29 A daily 5-minute conversation typically consisted of a greeting, social chat, and well-being check-in to determine whether the participant needed to progress or suspend their walking program and to provide empathic opportunities. After this, the participants were instructed to plug their pedometer into the system to upload their steps. Once this is done, the virtual coach reviews their progress relative to short-term and long-term goals (using a self-monitoring graph as shown in Figure 1), provides positive reinforcement if warranted, identifies barriers to walking and engages the participant in a problem-solving discussion for any barriers identified, then negotiates a new short-term goal if warranted.33 The session closed with an exercise tip of the day. Each day’s dialogue was varied in content and structure, and augmented with additional media to help maintain participant engagement and retention.14

Figure 1.

Screen shots of virtual coach system.

(top – animated coach; bottom – self-monitoring graph)

Table 1.

Dialogue Structure with Virtual Coach

|

During the baseline assessment visit, all subjects were given a training session on how to use the pedometer, and how to record their daily steps on paper log sheets. Participants were instructed to wear the pedometer daily for one month during all waking hours with the exception of showering, bathing or swimming. The researcher set up the pedometer with batteries and established the settings prior to giving it to subjects. The subjects were instructed to clip the pedometer on their belt or waistband. The mode was set on “step count” so that subjects would see how many steps they have walked. Subjects were not required to operate any of the other features on the pedometer. Subjects were also given a 15-minute training session on how to interact with the virtual exercise coach using the touch screen tablet computer and how to plug the pedometer into the tablet computer to allow the virtual coach to gather the step count data and provide the participant feedback regarding their progress. Subjects were then given a pedometer, paper log sheet and a tablet computer to take home. The computer was configured by the researcher with the subject’s given name and study identification number. Subjects were called by the researcher 2 days and 2 weeks after the baseline visit to inquire about technical issues and adverse events.

Analysis

Means, standard deviations and frequency distributions were calculated to describe subjects’ baseline characteristics, disease severity and exercise stages of change. Following the one-month intervention, means and standard deviations of the acceptability and usability outcome variables were calculated. Changes in the 6-minute and 10-meter walk test were analyzed using two-tailed paired t tests with the alpha level set at .05. All data analyses were conducted using SPSS version 16.0

RESULTS

Twenty-five subjects were screened for this study. Four subjects did not meet inclusion criteria (3 could not walk > 100 meters without a gait device; 1 was diagnosed with an atypical Parkinsonism) and 1 did not respond to calls to schedule a baseline assessment. Twenty persons with mild to moderate idiopathic PD participated. Subject characteristics are presented in Table 2. All participants (100%) completed the intervention and participated in the final assessment.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics

| Baseline Characteristics | Mean (SD) or Number (%) | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Female (%) | 11 (55%) | 31.5%~76.9% |

| Age (years) | 65.6 (5.6) | 62.93~68.17 |

| Disease Duration (years) | 3.0 (2.6) | 1.73~4.17 |

| Ethnicity - White | 20 (100%) | 83.2%~100% |

| Employment Status | ||

| Working | 10 (50%) | 27.2%~72.8% |

| Retired | 10 (50%) | 27.2%~72.8% |

| Mini-Mental Status Exam Score | 29.1 (1.5) | 28.39~29.81 |

| UPDRS (total) | 51 (17.71) | 42.71~59.29 |

| UPDRS (motor) | 32 (8.54) | 28~36 |

| Hoehn & Yahr Stage | ||

| 1.5 | 1 (5%) | 0.1%~24.9% |

| 2 | 13 (65%) | 40.8%~84.6% |

| 2.5 | 3 (15%) | 3.2%~37.9% |

| 3 | 3 (15%) | 3.2%~37.9% |

| Stages of Change | ||

| Pre-Contemplation | 1 (5%) | 0.1%~24.9% |

| Contemplation | 3 (15%) | 3.2%~37.9% |

| Preparation | 15 (75%) | 50.9%~91.3% |

| Maintenance | 1 (5%) | 0.1%~24.9% |

UPDRS = Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale

Usability and Acceptability

There were no technical difficulties using the pedometer and only one subject required a reminder of how to log into the computer during a call by the researcher on day 2 after the baseline training session. Interaction history revealed that participants logged-in an average of 25.4 days (SD 7) out of the recommended 30 days. On a 7-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7), participant satisfaction with the virtual coach was a mean of 5.6 (SD 1.7), desire to continue using virtual coach was a mean 5.7 (SD 1.7) and liking of the agent was a mean 5.6 (SD 1.6). Steps walked per day ranged from 644 to 11,943 steps per day.

Safety

No adverse events, in the form of falls, illnesses or injuries, occurred in any subjects during the study.

Efficacy

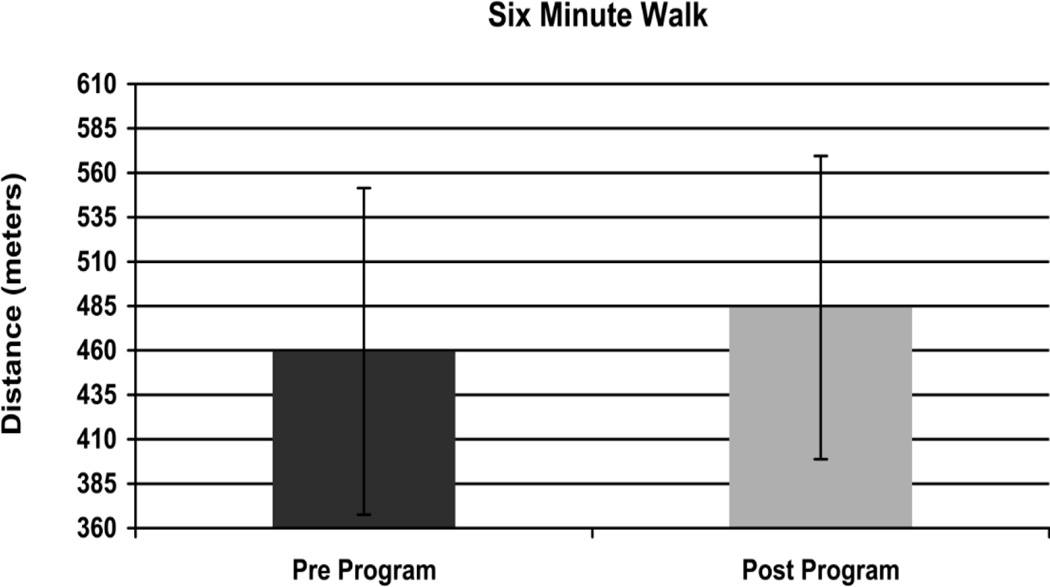

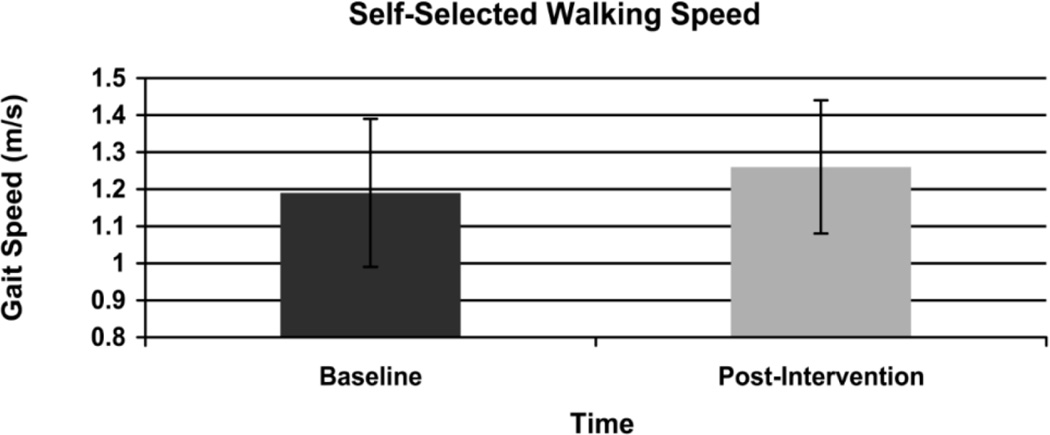

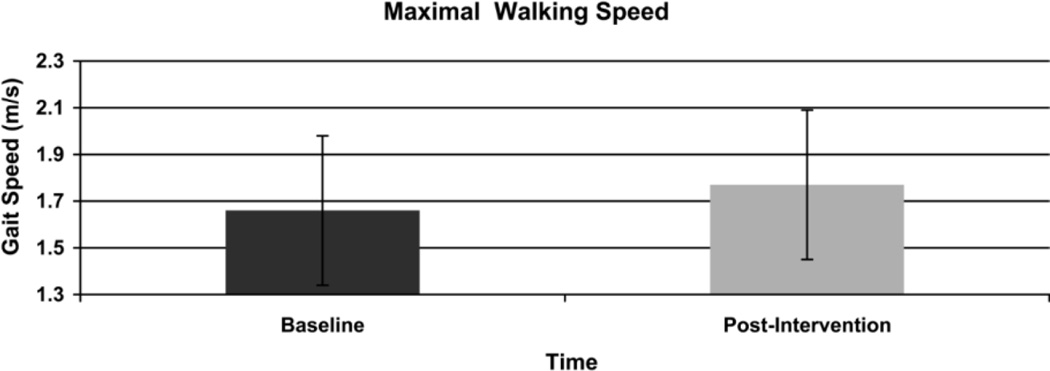

Walking distance improved significantly in the 6-MWT (Figure 2) from a mean distance of 459.5 (SD 91.9) meters at baseline to 484.1 (SD 85.3) meters post-intervention (p = .02). Gait speed also improved significantly in the 10 meter walk test (Figure 3). Self-selected walking speed improved from 1.19 (SD 0.2) meters per second at baseline to 1.26 (0.18) meters per second post intervention (p = .02). In addition, baseline maximum walking speed improved from 1.66 (0.32) meters per second to 1.77 (0.32) meters per second post intervention (p = .02) (Figure 4). Based on minimally clinically important differences (MCID) of 50 meters for the 6-MWT and .1m/s in the 10 meter walk test derived from the geriatric population,32 results in this pilot reveal a clinically meaningful change of.11m/s in maximum walking speed. Changes of 24 meters in the 6-minute walk test and .07m/s in the 10 meter self-selected condition did not exceed the MCID.

Figure 2.

Change in 6 Minute Walk Distance

Figure 3.

Change in Self-Selected Walking Speed

Figure 4.

Change in Maximal Walking Speed

DISCUSSION

One of the leading challenges faced by persons with Parkinson disease is to identify ways to improve adherence to exercise over the long-term in order to reduce disability. Virtual exercise coaches provide a new method to promote exercise adherence using an approach that can deliver a theoretically based intervention in an automated manner through building long-term, social-emotional relationships with people. We hypothesized that it would be feasible for persons with PD to interact with the virtual exercise coach in their home environments and adhere to a daily walking program in a safe manner. This Phase I clinical trial confirmed our initial hypotheses and revealed that persons with mild to moderate PD successfully used a virtual exercise coach at home over a one month period demonstrating initial feasibility of this approach. Participants logged into the tablet computer approximately 85% of the recommended number of days to interact with the coach and engaged in walking on a daily basis. Subjects found the virtual exercise coach to be acceptable, with high satisfaction rates and a desire to continue interacting with the coach. The walking program was safe with no falls or other adverse events occurring. Furthermore, statistically significant improvements in the 10-meter and 6-minute walk tests and clinically meaning improvements in maximum walking speed provide preliminary evidence of the efficacy of this approach in improving mobility outcomes in persons with Parkinson’s disease.

Many forms of technology (i.e., telephone, internet, e-mail and CD_ROM) have been used to promote behavioral change. However, these have several limitations. For example, automated telephone voice recognition programs require either clear pronunciation and/or accurate selection of keys from a telephone key pad.34 Both of these methods of interacting with the system are challenging for people with chronic degenerative conditions like PD due to the presence of tremor, reduced fine motor control and hypophonia. In a study of persons with Multiple Sclerosis, an internet-delivered behavioral coaching program, involving live interactions with a trained coach, was found to increase walking over a 3 month intervention period.35 While live interactions with health professionals are often effective in changing behavior, the cost of delivering these interventions on an ongoing basis is prohibitive, particularly for people with chronic degenerative conditions that require exercise participation for the rest of the participant’s life. The virtual exercise coach overcomes these limitations as it is less costly than live interactions with health care professionals or other trained personnel and can be more easily used by persons with motor impairments.

The most unique and potentially important characteristic of the virtual coach is its ability to build and maintain social-emotional relationships with people.10 Human contact is a key ingredient known to be effective in increasing adherence.36 In fact, most automated technologies used to promote behavioral change continue to rely on some human (i.e., therapist) contact to supplement the automated intervention, despite the expensive and time-intensive nature of live interactions with trained professionals. In a recent systematic review of technology-assisted approaches to behavior change in persons with chronic illness, authors concluded that “the continuing involvement of therapists in many interventions suggests that there is not, yet, an adequate substitute for the complex role they play.”36 The virtual coach, with its human-like characteristics, has the potential to fill this gap. The Virtual Coach differs from other technologies because it uses both visual and verbal information to build a relationship with the user that will facilitate behavioral change in the form of exercise adherence. The Virtual Coach emulates face to face interactions through visual cues such as hand gestures, facial expressions and body posture and verbal strategies such as humor and references to previous conversations.10 The goal of this tailored relationship building is to simulate the complexities inherent among human interactions resulting in improved adherence to the desired behavior.

This trial is significant because it is the first time that a virtual exercise coach has been used in people with a neurological disorder. Although this technology was been found to be successful in healthy adult populations (REF), it was necessary to establish that people with PD had no barriers to using the virtual exercise coach. In fact, subjects with PD found the virtual coach likable and expressed a desire to continue interacting with the coach. This trial has confirmed that people with PD are able to successfully use the virtual exercise coach in their home environments.

This study has several limitations. The sample size of this trial was small (n=20) and there was no control group, so the exploration of efficacy outcomes needs to be treated with caution. Despite the small sample, it is very promising to note that statistically significant gains in key mobility outcomes were observed after using the virtual exercise coach with clinically meaningful improvements observed in maximal walking speed. However, the intervention included both interacting with the virtual coach as well as using a pedometer; therefore the contributions of each to the improved mobility outcomes cannot be ascertained. Furthermore, subjects in our study volunteered to participate and may be more interested in exercising compared to the general PD population. This selection bias may have influenced our results and may limit the generalizability of our findings. Study duration was limited to one month; however, this was sufficient to address our primary aims related to feasibility in persons with PD. Although we recorded steps walked per day using pedometers, we did not determine baseline physical activity levels prior to the start of the intervention; therefore, improvements in activity level were not assessed in this preliminary study.

Future work in the area is needed to determine efficacy of virtual exercise coach in improving adherence to exercise in persons with PD over a longer-term period. A randomized controlled trial with a larger sample is essential to establish efficacy in this population and to determine the added value of the virtual coach compared to the value of the pedometer alone. Furthermore, the relationship between long-term exercise adherence and disability requires further study to determine if higher physical activity levels contribute to reductions in disability and greater independence in persons with a chronic progressive disease such as PD.

CONCLUSIONS

This Phase I clinical trial revealed that persons with mild to moderate PD successfully used a virtual exercise coach at home to adhere to a walking program over a one month period demonstrating initial feasibility of this approach. A Phase II clinical trial is needed to establish the efficacy of the virtual exercise coach to improve exercise adherence, physical activity levels and functional outcomes over the long-term in people with PD.

Supplementary Material

Table 3.

Baseline and Post intervention Physical Mobility Measures

| Physical Mobility Measures | Mean (SD) | 95% Confidence Interval |

T(df),p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline 10-meter self-selected speed (m/s) | 1.19(0.2) | 1.1~1.28 | −2.46(19), 0.02 |

| Post intervention 10-meter self-selected speed (m/s) | 1.26(0.18) | 1.17~1.34 | |

| Baseline 10-meter maximum speed (m/s) | 1.66(0.32) | 1.51~1.81 | −2.44(19), 0.02 |

| Post intervention 10-meter maximum speed (m/s) | 1.77(0.32) | 1.62~1.92 | |

| Baseline 6-MWT distance (m) | 459.49(91.94) | 416.46~502.52 | −2.55(19), 0.02 |

| Post intervention 6-MWT distance (m) | 484.12(85.33) | 444.18~524.05 |

m= meters; m/s = meters/second

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the American Parkinson Disease Association, Inc., Boston Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center; Boston University Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health - K12 HD043444; ProjectSpark; Boston University School of Public Health Pilot Project Fund. The virtual exercise coach system was developed, in part, under grant R01AG028668 from the National Institute on Aging.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures:

Financial disclosure statements have been obtained, and no conflicts of interest have been reported by the authors or by any individuals in control of the content of this article.

Previous Presentations: Ellis, T.D., Latham, N.K., DeAngelis, T.R., Thomas, C.A., Saint- Hilaire, M., Hendron, K.L., et al; Feasibility of virtual exercise coach to promote walking in community-dwelling persons with Parkinson's disease [abstract]. Movement Disorders 2012;27 Suppl 1:809; poster presentation at the Movement Disorder Society’s International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders; Dublin, Ireland: June 19, 2012

REFERENCES

- 1.Goodwin VA, Richards SH, Taylor RS, Taylor AH, Campbell JL. The effectiveness of exercise interventions for people with Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord. 2008;23(5):631–640. doi: 10.1002/mds.21922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwakkel G, deGoede CJT, van Wegen E. Impact of Physical Therapy for Parkinson's disease: A critical review of the literature. Parkinsonism and Related Disorders. 2007;13:S478–S487. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(08)70053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tomlinson CL, Patel S, Meek C, et al. Physiotherapy versus placebo or no intervention in Parkinson's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;7:CD002817. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002817.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leak RK, Zhang Z, Castro SL, et al. Impact of exercise on caudate and putamen in a non-human primate model of Parkinson's disease. Neuroimage. 2008;41:T58–T200. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tillerson JL, Caudle WM, Reveron ME, Miller GW. Exercise induces behavioral recovery and attenuates neurochemical deficits in rodent models of Parkinson's disease. Neuroscience. 2003;119(3):899–911. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahlskog JE. Does vigorous exercise have a neuroprotective effect in Parkinson disease? Neurology. 2011;77(3):288–294. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318225ab66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellis T, Cavanaugh JT, Earhart GM, et al. Factors associated with exercise behavior in people with Parkinson disease. Phys Ther. 2011;91(12):1838–1848. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20100390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duncan TE, McAuley E. Social support and efficacy cognitions in exercise adherence: a latent growth curve analysis. J Behav Med. 1993;16(2):199–218. doi: 10.1007/BF00844893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rhodes RE, Martin AD, Taunton JE. Temporal relationships of self-efficacy and social support as predictors of adherence in a 6-month strength-training program for older women. Percept Mot Skills. 2001;93(3):693–703. doi: 10.2466/pms.2001.93.3.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bickmore T, Caruso L, Clough-Gorr K, Hereen T. 'It's just like you talk to a friend' Relational Agents for Older Adults. Interacting with Computers. 2005;17(6):711–735. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bickmore T. Relational Agents: Effecting Change through Human-Computer Relationships. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paasche-Orlow MK, Silliman R, Winter M, Cheng D, Hanault L, Bickmore T. Efficacy of a Computer-based Intervention to Promote Walking in Older Adults; Annual Meeting of the American Geriatrics Society (abstract) 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jago R, Baranowski T, Baranowski JC, et al. Fit for Life Boy Scout badge: outcome evaluation of a troop and Internet intervention. Prev Med. 2006;42(3):181–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bickmore TW, Pfeifer LM, Byron D, et al. Usability of conversational agents by patients with inadequate health literacy: evidence from two clinical trials. J Health Commun. 2010;15(Suppl 2):197–210. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.499991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watson A, Bickmore T, Cange A, Kulshreshtha A, Kvedar J. An internet-based virtual coach to promote physical activity adherence in overweight adults: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(1):e1. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellis T, Cavanaugh JT, Earhart GM, Ford MP, Foreman KB, Dibble LE. Which measures of physical function and motor impairment best predict quality of life in Parkinson's disease? Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2011;17(9):693–697. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muslimovic D, Post B, Speelman JD, Schmand B, de Haan RJ. Determinants of disability and quality of life in mild to moderate Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2008;70(23):2241–2247. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000313835.33830.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shulman LM, Gruber-Baldini AL, Anderson KE, et al. The evolution of disability in Parkinson disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23(6):790–796. doi: 10.1002/mds.21879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cavanaugh JT, Ellis TD, Earhart GM, Ford MP, Foreman KB, Dibble LE. Capturing ambulatory activity decline in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2012;36(2):51–57. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0b013e318254ba7a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herman T, Giladi N, Hausdorff JM. Treadmill training for the treatment of gait disturbances in people with Parkinson's disease: a mini-review. J Neural Transm. 2009;116(3):307–318. doi: 10.1007/s00702-008-0139-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nieuwboer A, Kwakkel G, Rochester L, et al. Cueing training in the home improves gait-related mobility in Parkinson's disease: the RESCUE trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(2):134–140. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.200X.097923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Litvan I, Bhatia KP, Burn DJ, et al. Movement Disorders Society Scientific Issues Committee report: SIC Task Force appraisal of clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinsonian disorders. Mov Disord. 2003;18(5):467–486. doi: 10.1002/mds.10459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoehn MM, Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology. 1967;17(5):427–442. doi: 10.1212/wnl.17.5.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson WR, Gordon NF LSP. ACSM's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription Eighth Edition. Baltimore: Lipponcott Williams and Wilkons; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pelliccia A, Corrado D, Bjornstad HH, et al. Recommendations for participation in competitive sport and leisure-time physical activity in individuals with cardiomyopathies, myocarditis and pericarditis. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2006;13(6):876–885. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000238393.96975.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS): status and recommendations. Mov Disord. 2003;18(7):738–750. doi: 10.1002/mds.10473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marcus BH, Simkin LR. The stages of exercise behavior. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1993;33(1):83–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bickmore T, Gruber A, Picard R. Establishing the computer-patient working alliance in automated health behavior change interventions. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;59(1):21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fulk GD, Echternach JL, Nof L, O'Sullivan S. Clinometric properties of the six-minute walk test in individuals undergoing rehabilitation poststroke. Physiother Theory Pract. 2008;24(3):195–204. doi: 10.1080/09593980701588284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steffen T, Seney M. Test-retest reliability and minimal detectable change on balance and ambulation tests, the 36-item short-form health survey, and the unified Parkinson disease rating scale in people with parkinsonism. Phys Ther. 2008;88(6):733–746. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20070214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perera S, Mody SH, Woodman RC, Studenski SA. Meaningful change and responsiveness in common physical performance measures in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(5):743–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knapp D. Behavioral Management Techniques and Exercise Promotion. In: Dishman R, editor. Exercise Adherence: Its Impact on Public Health. Champaign, Illinois: Human Kinetics Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Friedman RH. Automated telephone conversations to assess health behavior and deliver behavioral interventions. J Med Syst. 1998;22(2):95–102. doi: 10.1023/a:1022695119046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Motl RW, Dlugonski D. Increasing physical activity in multiple sclerosis using a behavioral intervention. Behav Med. 2011;37(4):125–131. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2011.636769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosser BA, Vowles KE, Keogh E, Eccleston C, Mountain GA. Technologically-assisted behaviour change: a systematic review of studies of novel technologies for the management of chronic illness. J Telemed Telecare. 2009;15(7):327–338. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2009.090116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.