Abstract

Context

In 2004, the English Public Health White Paper Choosing Health introduced “health trainers” as new members of the National Health Service (NHS) workforce. Health trainers would offer one-to-one peer-support to anyone who wished to adopt and maintain a healthier lifestyle. Choosing Health implicitly envisaged health trainers working in community settings in order to engage “hard-to-reach” individuals and other groups who often have the poorest health but who engage the least with traditional health promotion and other NHS services.

Methods

During longitudinal case studies of 6 local health trainer services, we conducted in-depth interviews with key stakeholders and analyzed service activity data.

Findings

Rather than an unproblematic and stable implementation of community-focused services according to the vision in Choosing Health, we observed substantial shifts in the case studies’ configuration and delivery as the services embedded themselves in the local NHS systems. To explain these observations, we drew on a recently proposed conceptual framework to examine and understand the adoption and diffusion of innovations in health care systems.

Conclusions

The health trainer services have become more “medicalized” over time, and in doing so, the original theory underpinning the program has been threatened. The paradox is that policymakers and practitioners recognize the need to have a different service model for traditional NHS services if they want hard-to-reach populations to engage in preventive actions as a first step to redress health inequalities. The long-term sustainability of any new service model, however, depends on its aligning with the established medical system's (ie, the NHS's) characteristics.

Keywords: health trainer, health inequalities, policy implementation

In 2004, the public health white paper Choosing Health1 introduced health trainers (HTs) as new members of the English National Health Service (NHS) workforce. HTs would offer one-to-one peer-support to anyone who wished to adopt and maintain a healthier lifestyle, and health trainer services (HTSs) would be established in all primary care trusts (PCTs). Service users would be able to contact the HTS through the NHS (eg, via local health centers), but Choosing Health implicitly envisaged broader work for HTs in community settings in order to engage “hard-to-reach” individuals and communities with the new service. Although they would not be professionals (HTs were to be recruited from the local communities in which they would work), they would undergo accredited training and use evidence-based psychological techniques to help their clients decide on and reach their own goals regarding diet, exercise levels, alcohol use, and so forth.

The rationale for the HTS lay in the observation that those communities experiencing the worst health often engaged the least with traditional health promotion and other NHS services. The use of peer rather than professional workers drew on the growing evidence base underpinning approaches that recognized the need for workers to be attuned to how these service users lived their lives.2,3 Although the HTSs were to be available nationally, Choosing Health identified them as a key component of the government's health inequalities strategy and indicated that the HTSs first would target England's most disadvantaged populations.

Following the publication of Choosing Health, the Department of Health formed a team to develop the HTS policy further and to lead its implementation. The service was designed to be implemented in stages. A small number of “early adopters” were to be rapidly followed by service development in the 78 PCTs covering the most deprived areas of England, and then the service would be extended to all remaining PCTs. The service was not mandatory, however. The funds for implementing the HTSs were not ring-fenced, and although the PCTs could be advised that HTs were considered an important tool to reduce the burden of lifestyle-related diseases and to drive down health inequalities, ultimately it was up to the individual PCTs to decide how best to use these funds to meet the needs of their local population.4–6

In 2008 we began a review of the national implementation of the HTS policy in England. The data that have emerged from this review offer a unique, nearly complete story of a public health policy's conception, development, and implementation into the NHS as told by key stakeholders (policymakers, health care professionals, practitioners and managers, and the HTs themselves) and verified by triangulation with documentary analyses and interrogation of the performance management database developed to monitor HTS activity.

This article presents longitudinal observations of the implementation patterns of 6 local HTSs in England. Rather than an unproblematic and stable implementation of services according to the vision set out in Choosing Health, we observed substantial shifts in HTS configuration and delivery as services sought to embed themselves in local health systems. Drawing on qualitative fieldwork and service activity data, we describe the initial model of delivery adopted by each service and contrast this with models that the services have then adopted during attempts to integrate with the local NHS. To explain these observations, we draw on a recently proposed conceptual framework to examine and understand the adoption and diffusion of innovations in health care systems.

Following a brief description of our methods, we introduce our conceptual framework, describe and explain the changes observed in our case study HTSs, and conclude with a discussion of the implications for similar health promotion interventions targeted at improving health and reducing health inequalities.

Methods

In-Depth Case Studies of Health Trainer Services

Case study services (A through E) were purposively sampled to include a range of service provider arrangements (NHS, third-sector organization [TSO]), geographical locations (urban, urban/rural), and populations served. We also included 1 case study in which a service had not been established (F).

We conducted in-depth interviews (n = 118) with a range of stakeholders in selected case study services, including HTS managers and coordinators, HTs, directors of public health, commissioners, and staff in partner TSO providers. We visited each service at least twice and conducted follow-up interviews. Our first visits took place in late 2009/early 2010, with our final follow-up visits 12 to 18 months later. The interviews were designed to provide:

Detailed accounts of service establishment and development over time, including relevant local organizational context and history.

An understanding of the local service's current provision and settings.

Stakeholders’ perspectives on the HT role and concept.

Stakeholders’ experiences of working with and in local HTSs.

Perspectives on the impact of local HTSs.

HTs’ accounts of working, including details of their personal experience and perspectives on the impact of the role on themselves and their clients.

Interview schedules were tailored for each stakeholder group. In the initial interviews, we asked about the established local service models, including any developments since their inception. Follow-up interviews provided updates of the service model's development. We designed the interviews to explore both the local service's implementation and development and the participants’ own explanations of them.

The research team also was given all of the client data recorded in the national health trainer's Data Collection and Reporting System (DCRS) from January 2006 to December 2011. Data specific to each of the active case studies were abstracted for 6-month time periods from January 2006 to December 2011, and the following measures were calculated:

Number of new clients recorded.

Percentage of clients setting a personal health plan (PHP) in which the target behavior change and goals are identified and agreed on.

Throughput (number of clients setting a PHP divided by the number of whole-time equivalent HTs recorded as working in the service).

Percentage of clients setting a PHP with a referral source recorded as from a general practitioner (GP) or other primary care health professional.

Where appropriate, these data have been supplemented by documentary analysis of within-service and the Department of Health team's implementation documentation.

Analysis of Interviews

We recorded the interviews with the participants’ consent and transcribed them verbatim for analysis. We conducted a thematic analysis of their content, based on the Framework analytical approach.7 After an initial review of the transcripts, the coding and thematic development proceeded iteratively with ongoing discussion among the team. The analyses presented here focus on our comparative findings across individual case study services, including recurrent cross-case observations and themes. Our interview analysis was cross-referenced with the analysis of DCRS data, providing triangulation across data sources.

To interpret our observations, we drew on a recently proposed conceptual framework to examine and understand the adoption and diffusion of innovations in health care systems. We did not use this framework during the construction, execution, or analysis of the interviews, only during the discussion of our findings, as the framework was not published until 2010, after our study had begun.

The Conceptual Framework

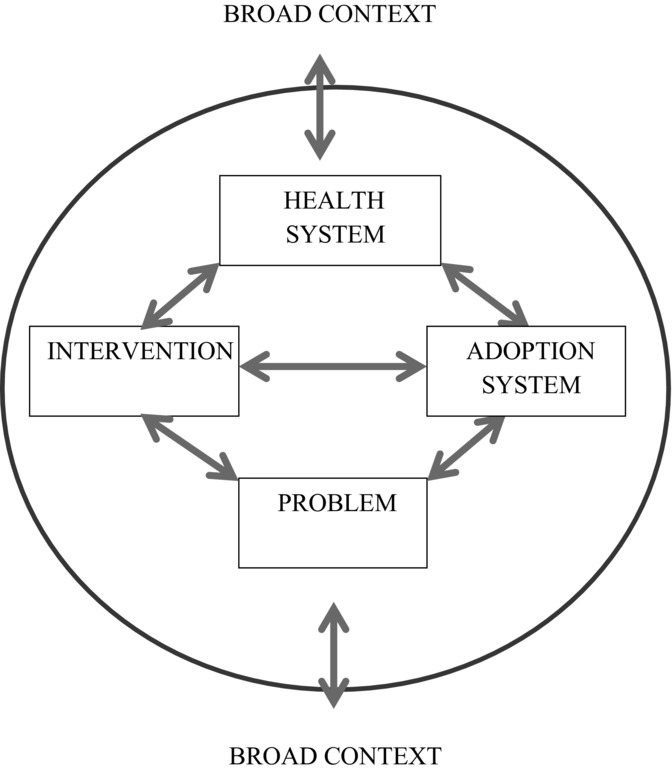

There is an extensive literature drawing from multiple disciplines on how the implementation of interventions into the NHS may be improved (for a substantial review and recommendations, see Greenhalgh and colleagues8). Greenhalgh and colleagues review highlights the predominance of research directed at understanding implementation as the sum of the actions by a series of individuals, in contrast to the lesser body of work focused on understanding factors operating at the organizational level. More recently, attention has turned to the organizational and higher systems levels, including the wider sociopolitical and other contexts in which health systems operate. Here, Atun and colleagues' conceptual framework for the “integration” of complex new interventions into existing health systems is timely, offering an analytical approach that considers critical health system functions.9,10

Atun and colleagues' conceptual framework posits that the success of an intervention being integrated is determined not only by the “fit” of the intervention with the critical functional characteristics of the targeted host (here the NHS) but also by a series of other factors modulating this relationship. The challenge is for an intervention to remain faithful to its theoretical and evidence-based origins, which determine its efficacy (“implementation fidelity”11,12), while at the same time being able to flex sufficiently to “fit” the host organization's requirements and hence ensure integration and longer-term sustainability.

Atun and colleagues conceptualize health care systems as complex adaptive systems constantly changing in response to internal and external triggers.13 Actions operating in a nonlinear fashion may have consequences that are not always immediately predictable. Such systems also exist in broader sociopolitical contexts that influence system elements, and vice versa. Health care innovations must be assimilated by specific “adoption systems” composed of individuals, organizations, and professional groups. Each member of the adoption system may have specific and preformed attitudes, values, and norms that in turn will influence receptivity to the innovation. Interactions among the innovation, health system, adoption systems, and broader context will determine how innovations are adopted (or not) and also will shape and reshape the innovation itself: “Often, the adoption involves not just changes in service content but regulatory, organizational, financial, clinical and relational changes involving multiple stakeholders. These interactions shape and transform the innovation to ensure alignment of its elements with critical health system functions in line with stakeholder expectations.”9(p108)

The extent to which a new intervention is integrated into a health system through any of these critical functions is influenced by a number of factors (Figure 1). First are the perceptions of the problem that the intervention is designed to address, for example, nature and scale. Second are the facets of the intervention itself, such as the perceived attributes (eg, conferring advantage over existing interventions, compatibility with the health system14 and intervention complexity, such as the number of components and organizations/actors that must interact with the intervention). Third is the receptivity of the adoption system, which comprises the key actors and institutions in the health system. Fourth is the health system characteristics as defined by its critical functions (governance, financing, planning, service delivery, monitoring and evaluation, and demand generation—for definitions of these concepts and how they are used in the HTS policy, see Table 1), and, finally, broader contextual influences that might include, for example, the political, economic, and social environments and the interplay between them.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework for Analyzing Integration of Targeted Health Interventions Into Health Systemsa

Table 1.

Definition of Key Constructs in Conceptual Framework for Analyzing Integration of Targeted Health Interventions Into Health Systemsa

| Conceptual Definition | Operational Definition |

|---|---|

| The problem is the disease or precursor of disease at which the intervention (see below) is targeted. | Reducing health inequalities through a focus on lifestyle and health-related behaviors (including smoking, diet, exercise, alcohol, and drug use), seen as precursors of the development and exacerbation of chronic diseases like diabetes, heart disease, and cancer. |

| The intervention is a novel set of technologies, behaviors, routines, and ways of working and delivering services that is directed at improving health outcomes and is implemented by planned action. | The Health Trainer Services (HTSs), in which accredited peer workers (the health trainers, HTs) engage with “hard-to-reach” (and other) individuals and communities to provide one-to-one motivational support and advice directed to achieving healthier lifestyles and less risky health-related behavior. |

| The adoption system is the key actors and institutions of the local health system and, beyond this, nonhealth organizations and others with a stake in both the problem and the intervention. | Individuals working in the local NHS (PCTs, GPs, and trusts) and third-sector organizations subcontracted to deliver the HTSs. They also include individuals in local authorities and other organizations offering other lifestyle services (eg, commercial weight-loss programs), as well as the service users themselves and their wider communities. |

| The health system characteristics are those critical functions the health system must undertake to achieve its objectives in regard to improving users’ health. These functions include stewardship and governance, financing, planning, service | Governance: Peer workers (the health trainers) are safe and competent to work with service users. Financing: HTSs have clearly demarcated and sustained funding. Planning: HTS's activities are aligned with the attainment of the health services' priorities and goals. Service Delivery: HTs meet the service standards and expectations of equivalent NHS services. |

| delivery, monitoring and evaluation, and demand generation. | Monitoring and Evaluation: HTs are able to demonstrate their activities and impacts clearly and consistently. Demand Generation: HTS's are able to generate and capture “sufficient” demand from targeted communities to deliver a cost-effective service. |

| The context is the wider political-economic, legal, and sociocultural environment in which the health system resides. | These include (1) the changing NHS structures, especially the split between the commissioner and the provider and subsequent reorganizations; (2) the political focus on individual rather than societal determinants of health and on the ring-fencing of health budgets; and (3) the broader context for health-related lifestyles and behaviors for many targeted individuals, including the direct effects and prioritization of social determinants of health. |

Derived from Atun et al.10

Findings

Next we describe our case study HTSs and the longitudinal changes in service delivery and configuration, and then we analyze these changes according to our conceptual framework. Table 2 gives a summary and a comparison of the case studies’ characteristics at start-up and at the final follow-up visit by the research team.

Table 2.

Summary of the Changes in the Characteristics of the 6 Case Studies at Start-up and Then at Follow-up

| Case Study Service | Time Perioda | Provider/s | Funding | Senior Buy-in?b | Primary Referral Source/s | Health Trainers | Geographical/Population Service Targeting? | Formal PMc System Established? | Health Trainer / Service User Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A Established in early 2007 to serve a large town | Start-up | Multiple TSOs | PCT | Yes | Self/communityd | “Person next door” | Locally defined deprived areas | No | 1-2-1 behavior changee |

| Follow-up | Single TSO | PCT | Senior champion left PCT | CVD risk assessment; smoking cessation; self/communityd | “Person next door” | Locally defined deprived areas | Yes | 1-2-1 behavior changee; CVD risk assessment “contact” | |

| B Citywide service starting in early 2006 | Start-up | Single TSO | PCT | Yes | Self/communityd | “Person next door” | Yes | No | 1-2-1 behavior changee |

| Follow-up | 2 TSOs (1 lead organization) | PCT | Yes | GP referral (prioritized); self/communityd | Some preference for more work-ready HTs | No | Yes | 1-2-1 behavior changee (early PHP setting prioritized) | |

| C Serving mixed urban/rural area from late 2006 | Start-up | PCT and 2 TSOs | Local “nonhealth” public-sector project and regeneration funding | Yes | Via local public-sector project; self/communityd | “Person next door” | Locally defined deprived areas | No | 1-2-1 behavior changee |

| Follow-up | PCT and 2 TSOs | PCT | Yes | Self/communityd | “Person next door” | Locally defined deprived areas | Yes | 1-2-1 behavior changee (early PHP setting prioritized) | |

| D City-based service beginning in early 2007 | Start-up | Multiple TSOs | PCT | No | Self/communityd | “Person next door” | Resident of 20% most deprived local area | No | 1-2-1 behavior changee |

| Follow-up | Single external provider | PCT | No | GP referrals | Mix of original health trainers and re-badged external provider staff | Universal | Yes | Telephone-based assessment and referral | |

| E Serving a large town from early 2006 | Start-up | PCT | PCT | Yes | Self/communityd | “Person next door” | Locally defined deprived areas | Yes | 1-2-1 behavior changee |

| Follow-up | PCT | PCT | Yes | Social marketing of and integration with weight management care pathway; GP referrals | Some preference for more work-ready HTs | Universal | Yes | Entry point for local weight management service / 1-2-1 behavior changee | |

| F Mixed urban/rural area where service was not commissionedf | Start-up | N/A | N/A | Nof | Intended GP-focused | Re-badged/trained primary care staff | Unclear | N/A | 1-2-1 behavior changee |

| Follow-up | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

Start-up: time point for service establishment; follow-up: last follow-up of case study by research staff.

Interviewees indicated that senior managers and/or PCT board members explicitly backed the HTS policy and local service.

PM = performance management.

Through health events, work with community health development workers, and other HT-led demand generation (eg, drop-in work, group activities, GP engagement). Please note, all services have been open to referrals from NHS professionals from inception, without explicitly targeting this source of demand.

Client led. Although health trainers are supposed to facilitate health-related lifestyle change (diet, smoking, exercise, alcohol), some services have expressly acknowledged that goals relating to broader social determinants of health may need to be addressed.

Intended delivery in proposed service.

Longitudinal Changes in Service Models of Delivery

Each active case study (A–E) initially had substantial commonality of delivery, as the local HTSs sought to interpret the HT policy within service models aligned with many of the ideas outlined in Choosing Health (Table 2). First, the recruitment processes and criteria attempted to implement the “person next door” concept in order to recruit HTs who appreciated the issues and the living circumstances of the target clients. Second, 4 of the 5 services targeted their available workforce in areas and communities defined by assessments of relative local deprivation, with the fifth implicitly acknowledging that the HTs were to prioritize such communities, but without specific geographical targeting. Third, most of the time, the HTs in all services worked out of bases in community settings and venues in the targeted areas, in order to generate a substantial client base directly from the community or non-NHS sources. In other words, the services were designed to be predominantly “community facing.” Any differences among the HTSs were at the provider level. Case Study E chose to deliver the service through an NHS provider; 2 of the case studies (C and D) opted for mixed NHS and TSO provision; and 2 outsourced provision to TSOs exclusively (Case Studies A and B).

Over time however, the case study services tended to become more “NHS facing,” for example, by engaging in the delivery of other NHS priorities (Case Study A), through integration with local care pathways (eg, for obesity management) and clinical services (Case Study E), and increasingly through attempts to engage with and satisfy the requirements of GPs as a targeted referral source (Case Studies B and D). Some services also changed aspects of their delivery, including the introduction of uniforms, appointment systems with central referral pathways and online bookings, and out-of-hours and weekend working—changes that also have been observed in other types of peer health worker programs in both the United States and the United Kingdom.15–17 Only Case Study C reported being able to maintain a “community-facing” service model.

Moves to more NHS-facing service models resulted in marked increases in client throughput, with an increasing proportion coming from direct referrals by GPs in Case Studies B and D (Table 3). The implications of this were varied and included, for example, changes in the nature of the service user–HT interaction (all case study services) and moves to more universal service coverage (Case Studies D and E).

Table 3.

Activity Data for Individual Case Studies and All Services in England

| January 2006 | January 2007 | January 2008 | January 2009 | January 2010 | January 2011 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time Period | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| Case Study A | ||||||||||||

| New clients | — | — | — | — | 58 | 80 | 108 | 734 | 3,095 | 2,569 | 1,444 | 785 |

| PHPs agreed (n; %)a | — | — | — | — | 42 (72.4) | 59 (73.8) | 75 (69.4) | 153 (20.8) | 458 (14.8) | 427 (16.6) | 778 (53.9) | 572 (72.9) |

| Throughputb | — | — | — | — | 4.94 | 7.32 | 5.17 | 8.26 | 31.33 | 23.72 | 44.57 | 32.16 |

| GP referrals (n; %)c | — | — | — | — | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.7) | 5 (6.7) | 5 (3.3) | 12 (2.6) | 16 (3.8) | 16 (2.1) | 37 (6.5) |

| Case Study B | ||||||||||||

| New clients | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 272 | 616 | 774 | 1,163 | 1,397 |

| PHPs agreed (n; %) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 155 (57.0) | 469 (76.1) | 642 (82.9) | 985 (84.7) | 1,204 (86.2) |

| Throughput | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 12.48 | 44.21 | 41.21 | 62.87 | 76.88 |

| GP referrals (n; %) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 53 (34.2) | 117 (25.0) | 328 (51.1) | 663 (67.3) | 895 (74.3) |

| Case Study C | ||||||||||||

| New clients | — | — | 29 | 75 | 89 | 44 | 75 | 101 | 119 | 109 | 81 | — |

| PHPs agreed (n; %) | — | — | 28 (97.6) | 63 (84.0) | 67 (75.3) | 36 (81.8) | 71 (94.7) | 86 (85.1) | 107 (89.9) | 87 (79.8) | 71 (87.7) | — |

| Throughput | — | — | — | 21.72 | 13.88 | 5.22 | 9.07 | 8.45 | 10.27 | 7.96 | 6.28 | — |

| GP referrals (n; %) | — | — | 1 (3.6) | 5 (7.9) | 7 (10.5) | 5 (13.9) | 11 (15.5) | 15 (17.4) | 34 (31.8) | 23 (26.4) | 23 (32.4) | — |

| Case Study D | ||||||||||||

| New clients | — | — | — | — | 293 | 326 | 396 | 395 | 407 | 431 | 924 | 1,945 |

| PHPs agreed (n; %) | — | — | — | — | 194 (66.2) | 233 (71.5) | 328 (82.8) | 363 (91.9) | 390 (95.8) | 389 (90.3) | 592 (64.1) | 1,685 (86.6) |

| Throughput | — | — | — | — | 20.86 | 22.62 | 24.44 | 22.47 | 25.72 | 22.85 | 34.65 | 104.19 |

| GP referrals (n; %) | — | — | — | — | 15 (7.7) | 44 (18.9) | 87 (26.5) | 135 (37.2) | 195 (50.0) | 160 (41.1) | 488 (82.4) | 1,394 (82.7) |

| Case Study E | ||||||||||||

| New clients | — | 50 | 323 | 404 | 1,905 | 1,488 | 1,628 | 1,243 | 1,060 | 901 | 1,305 | 995 |

| PHPs agreed (n; %)d | — | 14 (28.0) | 194 (60.1) | 187 (46.3) | 1,469 (77.1) | 1,208 (81.2) | 1,460 (89.7) | 1,007 (81.0) | 1,135 (107.1) | 925 (102.7) | 1,429 (109.5) | 1,150 (115.6) |

| Throughput | — | 2.15 | 30.0 | 17.81 | 140.38 | 73.33 | 79.08 | 57.71 | 65.03 | 53.09 | 82.06 | 66.16 |

| GP referrals (n; %) | — | 6 (42.9) | 74 (38.1) | 68 (36.4) | 140 (9.5) | 219 (18.1) | 434 (29.7) | 332 (33.0) | 400 (35.2) | 234 (25.3) | 217 (15.2) | 169 (14.7) |

Clients agreeing to a personal health plan (PHP) within a time period.

Clients agreeing to a PHP divided by the number of whole-time equivalent health trainers recorded for each time period.

Clients referred by a GP or other primary care source within a time period.

Where this exceeds the number of new clients within a specified time period, this indicates that existing clients are setting additional PHPs.

Over time, we also observed the rationalization of provider arrangements, most often a change from multiple TSOs to single larger organizations better able to “cope” with service delivery that needed to be aligned more explicitly with NHS principles. This culminated with the services in Case Study A being taken over by an out-of-area provider, Case Study D moving to a single external provider, and Case Study E's service becoming part of the local acute trust's provision.

Why Have These Shifts in Service Models Occurred?

Atun and colleagues' conceptual framework (Figure 1) suggests that innovations are gradually adopted and assimilated in an unpredictable manner, which often necessitates shifts in the interventions’ shape and content in order to align with key health system functions and with broader contextual factors. Next we analyze the shifts observed in the case study HTSs according to each framework element: the problem, the intervention, the adoption system, the health system's characteristics, and the broader context.

The Problem

The Labour governments from 1997 to 2010 generated policy initiatives targeted directly or indirectly at reducing health inequalities. While the HTS initiative was not launched until well into the Labour administration's second term, some elements of the program (eg, the focus on individual risk factors for ill health, the need for greater emphasis on prevention, the role of nonprofessionals in providing health advice, and the flexibility for services to be tailored to local needs) were being set out from 1998 onward in public health policy documents.18–21 Interviewees in all case studies acknowledged the concordance of the HTS policy with the wider political health care environment. They also recognized the need for a preventive agenda to shift the distribution of “unhealthy” behaviors. But at a time of financial pressures, they also suggested that it was easier to pull back from funding preventive services such as the HTS than to make cuts to frontline acute care. Here we should note that none of the active case studies had sufficient resources to recruit their original target number of HTs, with most employing around 15 at any one point (eg, Case Study B originally intended to have a citywide service of around 100 full-time equivalent HTs).

The Intervention

Drawing on the work by Rogers,14 Atun and colleagues argued that the more complex an intervention is, the more challenging it is to integrate (Box 1).9 This challenge is compounded when the perceived benefits are not readily apparent and in a time frame that allows them to be “observable,” or when they cannot be linked in a cause-and-effect relationship to the specific intervention.

Box 1 Intervention Complexitya

Multiple elements versus few elements.

Multiple episodes of delivery versus a single episode.

Multiple stakeholders versus few stakeholders.

Multiple levels of delivery versus few levels.

High-user engagement versus low-user engagement.

Behaviorally dominant versus technologically dominant.

The “community-facing” HTS intervention is a highly complex service innovation, comprising psychological behavior change approaches delivered in community settings, requiring the engagement of targeted individuals and communities, and involving multiple actors (eg, the HTs, other health care professionals, and service users) and, often, several organizations. Central to engaging the targeted service users in the behavioral change process is the prior establishment of a trusting relationship between the service user and HT, one that needs to be sustained through multiple contacts over a period of time. Even when this relationship is established, the service user's initial goals may be more “upstream” than simple lifestyle changes, with the social determinants of health reported by HTs as being common contingencies for achieving “downstream” client health-related behavioral change (see “Governance”).

At the heart of the HTS intervention is the peer delivery mechanism. Our data demonstrate that HTSs have experienced difficulty implementing the “person next door” concept as set out in Choosing Health (reported in all case studies) and that recruitment has been resource intensive, complex, and out-of-the-ordinary for the NHS. In turn, supporting new recruits through the accredited training process was reported as often challenging when working with recruits with little health care and/or educational experience. Management interviewees commented that the original policy had not sufficiently recognized the difficulty of supervising the newly qualified HTs. Having been recruited from disadvantaged communities themselves, some HTs had challenging “social” and family issues to manage alongside their work. Managers also noted that even though HTs were expected to work independently to engage service users and manage their workloads, those who had not previously had paid work needed help acquiring the skills to work without supervision. A lack of fit with the demands of professional NHS environments also was mentioned frequently (eg, appearance, record keeping, data management, working in an accountable manner within strictly confined role boundaries). As each of the case studies gained experience with delivering their services, the interviewees reported that recruitment criteria were shifted from looking for minimal skills to attracting better-qualified recruits. The national DCRS data appear to support this observation, suggesting that 29% of HTs held a university degree or equivalent qualification in financial year 2008/2009.22

The Adoption System

Four groups of actors have influenced longitudinal changes in case study services: senior stakeholders in PCTs, service commissioners, GPs and other health care professional groups, and targeted individuals and communities.

Senior PCT stakeholder buy-in was key to the establishment and sustainability of the case study HTSs, and usually this was reported to include directors of public health and PCT board members. In our case studies, support for the original “community-facing” model of delivery varied from the very strong (Case Studies A, B, C, and E) to the hostile (Case Study F). In Case Study D, there was overt skepticism concerning the utility of a community-based lifestyle intervention, but the case study initially supported implementation of the service because it enabled the PCT to demonstrate cardiovascular disease prevention work among disadvantaged local communities. Lack of senior buy-in has prevented service establishment (Case Study F) and contributed to fundamental service reconfiguration away from a face-to-face HTS (Case Study D).

Related to this were the perspectives of the PCT commissioning staff, concerned with judging and managing the HTSs’ performance in the same ways as other NHS services (including activities defined by the number of service users completing PHPs). Thus low-throughput, “community-facing” service models reported difficulty winning value-for-money arguments (see “Demand Generation”).

When adopting a new intervention, each actor will have differing perceptions of its benefits and costs. These perceptions are linked to how well an intervention conforms to existing norms and experiences, so the attitudes of professional groups within the NHS are important here. As the HTSs were implemented, most reported challenges from GPs, primary health care staff, and other professional NHS staff with a preventive health remit (eg, dieticians, smoking cessation workers) who were skeptical of the validity of employing relatively unqualified “peers” to deliver health care. Here the lens through which the HTs were viewed is biomedical, with professionals questioning how a person with no professional qualifications can legitimately “see patients” and not recognizing that the HTS “intervention” is as therapeutic through its contextual peer relationship as through the delivery of psychological behavior change interventions. Ferlie and colleagues explored the social and cognitive boundaries between professional groups even when working in a single NHS multidisciplinary setting and argued that when these groups have different epistemologies, “innovations that do not bridge these divides will literally be judged incredible.”23(p131) Accordingly, and as GPs become more powerful in new commissioning roles, we observed Case Studies B and D in particular trying to align their service delivery more closely with this group's norms, expectations, and priorities.

Finally, Atun and colleagues' adoption system also includes the targeted service users and communities of the new intervention. In all case studies, local populations did not appear to have demonstrated the level of demand for lifestyle-focused interventions that was assumed in Choosing Health. This resulted in a “low throughput” for “community-facing” HTSs, which compounded the issues just discussed (see “Demand Generation”).

The Health System's Characteristics and Critical Functions

Governance

To fulfill the governance requirements, the HTs needed to be perceived as safe, competent, and trained. At first, the local services decided how to train their HTs in-house, but by 2007 the Department of Health's team had established an accredited national training program. The formalization of training did not, however, counter all negative perceptions of the HTs (see “The Adoption System”).

All the case studies discussed the need for the HTs’ accountability, including recording their activities for performance management purposes. A new national HT Data Collection and Reporting System (DCRS) that had been developed in one locality was adopted nationally and made available online for services and for their HTs to input simple workforce (eg, number of HTs, hours worked, number of clients seen) and client information (eg, name, postal code) from October 2006 onward. By 2009 the DCRS's minimum data set had been expanded substantially to capture a range of items that reflected health-related behavior (diet, alcohol, smoking, exercise) at both baseline and follow-up as reported by clients agreeing to a PHP with a HT. But the DCRS offered no mechanism to capture any activity undertaken by a HT as a necessary precursor to trying to change individual clients’ health-related behaviors, for example, working in the community to raise awareness of the service or with individual clients addressing more “upstream” problems (eg, debt, domestic violence, housing, substance misuse) that had to be resolved before considering lifestyle changes.

Dealing with these “upstream” issues was a central theme in our interviews across all the case studies. Although the HTS policy was intended to help people make health-related behavior changes, it soon became apparent—especially when working in the more deprived communities—that other, complex issues in the service users’ lives required attention. Our interviews with the HTs revealed that many had experienced similar issues in their own lives and that they felt compelled to try to help the service users address them, frequently using their own experiential knowledge, social networks, and resources. Many managers recognized the likelihood of HTs being drawn into these aspects of the service users’ lives and brought up the need for clear role boundaries for the HTs, for example, by making clear that activities other than lifestyle support were outside the local service's remit. Linked to this were managers’ comments about the need for HTs to maintain a “professional distance” while working with service users, thereby recognizing the inherent but unrecognized tension of a peer worker having to conform to the professional norms of the NHS environment.

Financing

The lack of ring-fencing of monies was a major issue for the services. Those localities tasked with developing a HTS needed to get a release of funds from their PCT's baseline allocation to implement the HTS policy. The degree to which this was possible varied substantially across the country and, to a significant extent, depended on the senior PCT colleagues’ support of the HTS policy.

In their workforce audit reports, the team from University College London estimated that of the £36 million earmarked for the national HTS in the first year (2006/2007), only £5.1 million (14.2%) was spent.24 In the following year, when the funding was increased to £77 million on a recurrent basis, NHS spending rose to £16.9 million (21.9%).25 Even when the PCTs released more funds, the majority of the funding commitments were on a nonrecurrent and short-term basis, thereby feeding the constant threat of services disappearing and jobs being lost.

Demand Generation

Chapter 5 of Choosing Health opens by stating that there is a “strong desire by millions of individuals in England to change to a healthier way of life”(p104) but that achieving sustained behavior change is difficult. This statement suggests that there was an unmet demand for lifestyle advice and support for behavioral change, thus providing the rationale for the new HTS intervention. Almost all the HTs we interviewed, however, reported difficulty in engaging with people in community-facing service models, and they noted the absence of an easily identifiable demand for help with lifestyle-focused behavior change. All case studies tried to overcome this, for example, through the provision of local events and group work (eg, walking groups), through integration of the HTs with local community health and development work and staff, and through delivery of services in partnership with those TSOs perceived to be more closely integrated with local communities. But none of these approaches was able to generate the volume of one-to-one lifestyle-focused client work that would enable the HTSs to be seen as legitimate, high-throughput NHS services. Thus the case study services, faced with low throughput, started to look for “work” elsewhere—be it integration with lifestyle-related care pathways, health checks, or reorientation to an already “captured” service user base (GP referrals).

Monitoring and Evaluation

Each case study adopted the national DCRS as a performance management system, which was reflected in the paperwork that the HTs were required to use to record and guide their activities with the service users. Both the DCRS and the service paperwork closely followed The NHS Health Trainer Handbook, which describes the behavioral change processes and approaches to be followed with service users.26 Our interviews with HTs who had worked with predominantly community-facing models as well as more NHS-facing services showed their frustration with the new requirements to use standardized templates to record their interactions with service users (overly structured and “unnatural”) and with their inability to record their broader impact and work outside lifestyle issues. In some very frank interviews, some HTs revealed that these frustrations had even led to them not always entering their clients’ data correctly (“I can't be bothered wasting all that time... oh, go on then, tick that box”), suggesting that the quality of the DCRS's recorded data may be poor.

The Broader Context

One major organizational change in the health system provided the background for many of our observations within the case study services. The emerging split between the commissioner and the provider in the function of PCTs coincided with attempts to develop and sustain the HTSs. This split placed the demand generation and related monitoring and evaluation functions in the spotlight, along with the need to demonstrate value-for-money in commissioned HTSs. Later, the further transfer of commissioning functions to GP groups sharpened the focus on the need to align the delivery of HTSs with the characteristics of “good” NHS services and to plan activities according to the primary care professionals’ defined needs.

Finally, for many targeted individuals and communities, the broader context for health-related lifestyle and behavior—that is, the importance of social determinants of health in framing behavior—was core to the within-service narratives of low demand for lifestyle intervention. As we noted, the interviewees in all case studies indicated that adverse physical, economic, and psychosocial factors were widely prevalent in the target communities and that these were the issues that many service users revealed to the HTs to be affecting their health and well-being. Many HT interviewees reported being “stressed” and upset by some of the situations they encountered and being frustrated that the DCRS, and the HTS policy more widely, did not acknowledge the legitimacy of the activities targeting the social determinants of health in individuals’ lives.

Discussion

Health inequalities in England have not narrowed despite the sustained policy emphasis (1997-2010) heralded by Tony Blair's first Labour government's commissioning of the Acheson Inquiry in 1997,18 which was widely recognized as the most comprehensive national inequalities strategy in the world to date.27 Rather, we have witnessed maintained or increased inequality across available indicators, despite improved health for most population groups regardless of social positioning.28 In 2008, the secretary of state for health invited Professor Michael Marmot to review the activities over the past decade and to propose principles to guide future policy development and implementation.

The Marmot Review was completed in 2010.29 Besides reflecting calls from the World Health Organization's Commission on Social Determinants of Health for action on social justice to address inequalities,30 the review also recommended that government strengthen the role and impact of preventing those conditions most closely related to health inequalities. Some critics argue that such “downstream” action might be assumed to be more palatable and sustainable in the current political climate than more fundamental work to address socioeconomic determinants of health, particularly redistributive action.31 Nonetheless, the diseases contributing most to the health inequalities gradient (cancer and cardiovascular disorders) are associated with tobacco use, diet, alcohol consumption, and lack of exercise. Modifying the health-related behaviors of socioeconomically disadvantaged groups thus might reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with the chronic diseases that drive the inequality gradient. Marmot was cautious, however, about the utility of universal health promotion activities, arguing that “some individuals may require additional support” and that “both population-wide and individually targeted interventions need to be proportionally targeted across the social gradient if they are to reduce health inequalities effectively.”29(p141) The review also pointed out that the identification and development of evidence-based interventions were insufficient by themselves. Instead, the key to reducing inequalities also requires a whole-system approach to local implementation and delivery, in which organizations, communities, and people work together: “Without citizen participation and community engagement fostered by public service organisations, it will be difficult to improve penetration of interventions and to impact on health inequalities.”29(p151)

In discussing the prevention of ill health, Marmot cited, among others, the idea of HTs as a means to reduce health inequalities among those with additional needs29(p144) and more generally as part of a wider public health workforce trained to deliver behavioral change interventions to local populations.29(p148) The review recognized that it was too early to tell if the HTS policy had “worked” but commented that the principles underpinning the policy idea cohered with evidence for likely effectiveness:

Initiatives using local health trainers, community health champions and community development work also show encouraging signs of empowering individuals to participate and take control of their health and well-being. The impact of such innovations in health inequalities has yet to be determined. However the approach facilitates greater participation of patients and citizens and support in developing health literacy and improving health and well-being.29(p155)

In this article we showed that the HTSs as envisaged in Choosing Health were a highly complex and novel intervention intended to help people to improve their health through the delivery, by peers, of lifestyle-focused behavior change interventions in community settings. These HTSs needed not only to develop and implement the mode of delivery outlined in Choosing Health but also to do so in a way that facilitated integration with the health system, thus providing sustainability beyond the lifetime of a government policy document.

Atun and colleagues' conceptual framework suggests a number of challenges for the “community-facing” model envisaged in Choosing Health. Although lifestyle and its associated risks are an accepted part of the NHS's remit, when financial push comes to shove, the problem addressed by preventive services will undoubtedly be deemed minor in comparison to those related to acute treatment services. We found that all case studies operated with a smaller workforce than originally conceived. The challenge was thus to integrate while the policy window was open. The complexity of the HTS idea (peer delivery, community focus, engagement with multiple actors and organizations) and the associated need to fit with the principal health service functions, however, threatened the rapid adoption by and assimilation into local health care systems. Observations across the case study services demonstrated that this fit was difficult for predominantly community-facing services to achieve and that NHS-facing shifts were required relatively early on in order for the services to survive. Even though most of the active case studies had senior PCT buy-in during their establishment, the primacy of professional biomedical approaches in the NHS adoption system became a challenge, along with the need to satisfy commissioners concerned with activity metrics as judgments of relative value-for-money. This was compounded by broader contextual shifts, including the split between the commissioner and the provider, the growing power of GPs in commissioning decisions, and difficulty in satisfying the demand generation health system function owing to the lack of a substantial, overt, and easily accessible demand for lifestyle support in targeted disadvantaged communities.

We observed obvious NHS-facing shifts in 4 of the 5 active case studies, which appeared to divert their services substantially from what the original policy plan envisioned. Changes in the referral base shifted the emphasis from HT-generated community activity toward NHS-defined priorities. Two case studies shifted from a health inequality focus (ie, targeted provision) to universal service provision. In all services, NHS-facing developments were reported to affect the HTs’ interactions with service users, for example, as a result of metric- and paperwork-driven approaches and the “conveyor-belt” nature of activity in response to local NHS priorities (eg, cardiovascular risk assessment). Some services implicitly changed their recruitment strategies, to a preference for more NHS work-ready candidates.

The only case study that seemingly avoided these shifts was Case Study C, in which at follow-up, despite recognition of these issues, the interviewees commented that they were able to maintain a predominantly community-facing service approach. They suggested that this was because of sustained senior buy-in and also as a result of early, high-profile public recognition of the service, which acted as a protective mechanism against NHS-facing pressures. Case Study F, in which a lack of senior buy-in combined with financial pressures prevented the establishment of services, essentially proposed a ready-made NHS-facing service that the local health service could accommodate. This was justified in part by reported “difficulties” in other local areas that had opted for community-facing approaches.

Our observations represent a serious challenge to the original policy theory, especially to the explicit assumption of an easily accessible demand for health-related lifestyle support and advice by individuals and communities traditionally targeted by health inequality policies. HTs in community-facing services unanimously reported the difficulty in engaging service users and the high prevalence of “upstream” issues relating to the broader social determinants of health revealed by clients once they had been engaged. The HTs also provided, however, numerous examples of when sustained contact and work with service users brought about fundamental change for the individual. Interviewees contrasted these achievements with the more cursory conveyor-belt work in some of the case studies responding to other NHS priorities. The national performance management system only made these challenges worse by legitimating only those activities directly targeted at achieving behavioral change and not recognizing the work needed to be done beforehand to address the adverse social determinants of health characterizing the lives of many “hard-to-reach” clients and disadvantaged communities. Our observations of the difficulty of finding the demand for lifestyle-focused behavior change work and the importance of social determinants of health are echoed in other local English health trainer evaluation work and evidence reviews.32–35 The difficulties of a rapid top-down implementation of national peer-delivered approaches in health care systems are not without precedence, having been observed in attempts to scale up community health workers’ (CHW's) interventions in other national contexts.36,37

While successful experiments across a variety of contexts provided the inspiration for CHW programs, numerous difficulties arose in the process of shifting from effective and small-scale local projects to national CHW schemes. Common problems included the lack of integration and conflict with health professionals, unrealistic expectations, unsupportive environments… . In many countries, CHW programs were introduced in an overly hasty top down manner with little planning. Rather than being the leading edge of a transformed approach to health care, CHWs often ended up becoming a poorly resourced and undervalued extension of the existing health service—“just another pair of hands.”36(p180)

Conclusion

If the HTS policy is to be sustainable in the NHS, the HTSs have to evolve in order to survive, for at no point do our data suggest that the HTSs were able to change the organizational structure or culture of the local NHS services to “fit” Choosing Health's original modus operandi. The policy and its implementation are examples of the tension between the need to adhere to the theory unpinning an intervention in order to achieve the stated objectives (implementation fidelity) and the need for model plasticity to facilitate successful integration in established health systems. The paradox is that policymakers do recognize the need to have a service model different from that of traditional NHS services if “hard-to-reach” populations are to engage in preventive actions as a first step to redress health inequalities. As our study of the HTS policy found, however, the long-term sustainability of any new health intervention service depends on its fitting the established system's (NHS's) characteristics.

Notes

Adapted from Atun et al.9

Funding/Support

This study was funded by the Department of Health Policy Research Programme (Grant number: PRP 018/0061). The Funding Body requires sight of manuscripts prior to publication (28 days) but played no role in the writing of the manuscript or in the decision to submit it for publication. Specifically there has been no involvement in data collection, analysis, or interpretation; study design; case study recruitment; or any aspect pertinent to the study.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. No disclosures were reported.

Policy Points

In 2004, England's National Health Service introduced health trainer services to help individuals adopt healthier lifestyles and to redress national health inequalities.

Over time these anticipated community-focused services became more NHS-focused, delivering “downstream” lifestyle interventions. At the same time, individuals' lifestyle choices were abstracted from the wider social determinants of health and the potential to address inequalities was diminished.

While different service models are needed to engage hard-to-reach populations, the long-term sustainability of any new service model depends on its aligning with the established medical system's characteristics.

References

- 1.Department of Health. Choosing Health: Making Healthier Choices Easier. London: Department of Health; 2004. November 16. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carr S, Lhussier M, Forster N. An evidence synthesis of qualitative and quantitative research on component intervention techniques, effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, equity and acceptability of different versions of health-related lifestyle advisor role in improving health. Health Technol Assess. 2011;15(9) doi: 10.3310/hta15090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.South J, White J, Gamsu M. People-Centred Public Health. Bristol: Policy Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health. Project initiation document: NHS health trainers program. London: Department of Health; 2005. September 28. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health. Project initiation document: NHS health trainers program—spearhead and 3rd parties implementation phase. London: Department of Health; 2006. April 20. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Health. Project initiation document: NHS health trainers program—embedding the service. London: Department of Health; 2007. September 25. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Burgess RG, editors. Carrying Out Qualitative Analysis. London: Routledge; 1994. pp. 219–262. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenhalgh T, Robert G. MacFarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004;82(4):581–629. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atun R, de Jong T, Secci F, Ohiri K, Adeyi O. Integration of targeted health interventions into health systems: a conceptual framework for analysis. Health Policy Plann. 2010;25:104–111. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czp055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atun R, de Jong T, Secci F, Ohiri K, Adeyi O. A systematic review of the evidence on integration of targeted health interventions into health systems. Health Policy Plann. 2010;25:1–14. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czp053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carroll C, Patterson M, Wood S, Booth A, Rick J, Balain S. A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implementation Sci. 2007;2:40. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-2-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breitenstein S, Gross D, Garvey C, Hill C, Fogg L, Resnick B. Implementation fidelity in community-based interventions. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33:164–173. doi: 10.1002/nur.20373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plsek P, Greenhalgh T. The challenge of complexity in health care. BMJ. 2001;323:625–628. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7313.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th ed. New York, NY: Free Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kennedy LA, Milton B, Bundred P. Lay food and health worker involvement in community nutrition and dietetics in England: roles, responsibilities and relationship with professionals. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2008;21(3):210–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2008.00876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aiken A, Thomson G. Professionalisation of a breast-feeding peer support service: issues and experiences of peer supporters. Midwifery. 2013;29(12):145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Love MB, Legion V, Shim JK, Tsai C, Quijano V, Davis C. CHWs get credit: a 10-year history of the first college-credit certificate for community health workers in the United States. Health Promotion Pract. 2004;5(4):418–428. doi: 10.1177/1524839903260142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Department of Health. The independent inquiry into inequalities in health (the Acheson Report) London: Stationery Office; 1998. November 26. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Department of Health. Saving lives: our healthier nation. London: Department of Health; 1999. June 1. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Department of Health. Securing our future health: taking a long-term view. London: Department of Health; 2002. June 1. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Treasury HM. Securing good health for the whole population. London: HM Treasury; 2004. February 25. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith J, Gardner B, Michie S. National health trainer activity report for 2008/09. London: Centre for Outcomes Research and Effectiveness, Department of Psychology, University College; January 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferlie E, Fitzgerald L, Wood M, Hawkins C. The non-spread of innovations: the mediating role of professionals. Acad Manage J. 2005;48(1):117–134. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilkinson D, Jain P, Hyland L, Michie S. National health trainer activity report for 2006/07: a report for the Department of Health inequalities unit. London: Centre for Outcomes Research and Effectiveness, Department of Psychology, University College; November 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith D, Gardner B, Michie S. National health trainer activity report for 2007/08: a report for the Department of Health social marketing and health related behaviour team. London: Centre for Outcomes Research and Effectiveness, Department of Psychology, University College; December 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michie S, Rumsey N, Fussell A. Improving Health: Changing Behaviour. The NHS Health Trainer Handbook. London: Department of Health; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mackenbach JP. Can we reduce health inequalities? An analysis of the English strategy, 1997-2010. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:568–575. doi: 10.1136/jech.2010.128280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Department of Health. Tackling inequalities in life expectancy in areas with the worst health and deprivation. London: The Stationery Office; 2010. Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General. July 2. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marmot M. Fair society, healthy lives: a strategic review of health inequalities in England post-2010. Marmot Review. 2010 February. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mackenbach JP. Has the English strategy to reduce health inequalities failed? Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:1249–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Attree P, Clayton S, Karunanithi S, Nayak S, Popay J, Read D. NHS health trainers: a review of emerging evaluation evidence. Crit Public Health. 2012;22(1):25–38. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ball L, Nasr N. A qualitative exploration of a health trainer program in two UK primary care trusts. Perspect Public Health. 2011;131(1):24–31. doi: 10.1177/1757913910369089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cook T, Wills J. Engaging with marginalised communities: the experiences of London health trainers. Perspect Public Health. 2011;132(5):221–227. doi: 10.1177/1757913910393864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.South J, Woodward J, Lowcock D. New beginnings: stakeholder perspectives on the role of health trainers. J Royal Soc Promotion Health. 2007;127(5):224–230. doi: 10.1177/1466424007081791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneider H, Hlophe H, van Rensberg D. Community health workers and the response to HIV/AIDS in South Africa: tensions and prospects. Health Policy Plann. 2008;23:179–187. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czn006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Ginneken N, Lewin S, Berridge V. The emergence of community health worker programs in the late apartheid era in South Africa: an historical analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:1110–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]