Abstract

Background

MicroRNA-32 (miR-32) is dysregulated in certain human malignancies and correlates with tumor progression. However, its expression and function in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) remain unclear. Thus, the aim of this study was to explore the effects of miR-32 expression on OSCC tumorigenesis and development.

Material/Methods

Real-time quantitative PCR was applied to evaluate the expression level of miR-32 in OSCC cell lines and primary tumor tissues. The association of miR-32 expression with clinicopathological factors and prognosis was also analyzed. In vitro cell proliferation, apoptosis, invasion, and migration assays were executed to elucidate biological effects of miR-32. Western blotting and luciferase assays were performed to confirm the regulation of EZH2 by miR-32.

Results

Down-regulation of miR-32 was found in OSCC tissues compared with corresponding noncancerous tissues (P<0.001). Decreased miR-32 expression was significantly associated with advanced T classifications, positive N classification, advanced TNM stage, and shorter overall survival (all P<0.05). Multivariate regression analysis corroborated that low-level expression of miR-32 was an independent unfavorable prognostic factor for OSCC patients. In vitro functional assays showed that overexpression of miR-32 reduced OSCC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, and promoted cell apoptosis. In contrast, miR-32 knock-down resulted in an increase in cell growth and invasiveness. Finally, we identified EZH2 as the functional downstream target of miR-32 by directly targeting the 3′-UTR of EZH2.

Conclusions

These findings indicate that miR-32 may act as a tumor suppressor in OSCC and could serve as a novel therapeutic agent for miR-based therapy.

MeSH Keywords: Cell Proliferation, MicroRNAs, Mouth Neoplasms, Neoplasm Invasiveness, Prognosis

Background

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is the sixth most common cancer worldwide and represents about 90% of all the oral malignancies [1]. Despite advances in clinical and experimental oncology, the prognosis of OSCC is still unfavorable due to its invasive nature, and the 5-year survival rates remain at less than 50% and have not improved in the last 3 decades [2]. Previous studies have demonstrated diverse genetic alterations in OSCC, but the molecular mechanisms underlying OSCC carcinogenesis and progression are highly complex, and further identification of new candidate molecules that take part in these processes is important for improving the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of this disease.

MicroRNAs (miRs) are a class of short (about 22 nucleotides in length), endogenous, single-stranded, non-protein-coding RNAs that directly bind to the 3′-untranslated regions (3′-UTRs) of target messenger RNAs (mRNAs), leading to mRNA degradation or translational suppression [3]. Accumulating research suggests that miRs play essential roles in the biology of human cancers, which may provide a new and promising way to deal with cancer [4]. Dysregulation of miR expression has been frequently reported and closely associated with tumor initiation, promotion, and progression [5–7]. In terms of miR-32, it is up-regulated in colorectal cancer [8], kidney cancer [9], prostate cancer [10], and multiple myeloma [11], and acts as a potential oncogene in these tumors. In contrast, miR-32 is significantly decreased in gastric cancer and osteosarcoma and acts as a candidate tumor suppressor [12,13]. However, the biological function of miR-32 in OSCC and its clinicopathologic significance remain poorly understood.

Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) is a member of the Polycomb group gene family and is involved in cell cycle regulation and carcinogenesis[14]. Sustained activation of EZH2 can lead to abnormal proliferation and malignant transformation of cells [15]. Overexpression of EZH2 in OSCC is correlated with malignant potential and poor prognosis [16]. Intriguingly, several miRs, such as miR-101 [17], miR-144 [18], and miR-200c [19], participate in the regulation of EZH2 activity in different tissues, but the potential regulatory effect of miR-32 on EZH2 expression in OSCC has not been confirmed.

In the present study, we focused on the expression and function of miR-32 in OSCC. We found that miR-32 was downregulated in OSCC compared with corresponding noncancerous tissues. Decreased miR-32 expression was significantly correlated with aggressive clinicopathological features and poor survival. In vitro functional assays demonstrated that overexpression of miR-32 reduced OSCC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, and promoted cell apoptosis. In contrast, miR-32 knock-down resulted in an increase in cell growth and invasiveness. Finally, EZH2 was identified as a direct target of miR-32 by luciferase reporter assay. Our novel findings suggest that aberrant miR-32 expression contributes to OSCC development. miR-32 may act as a novel diagnostic and prognostic marker and is a potential target for molecular therapy of OSCC.

Material and Methods

Patients and clinical specimens

Paired OSCC and adjacent noncancerous tissues were obtained from 109 pathologically confirmed primary OSCC patients at the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, School and Hospital of Stomatology, Wenzhou Medical University, P. R. China between January 2006 and December 2009. These tissues were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately after resection and stored at −80°C until use. None of the patients had received neoadjuvant chemo- or radio-therapy before surgery. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Follow-up information was available for all patients. Overall survival was defined as the time from the day of operation to death or, for living patients, the date of last follow-up. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of our hospital, and written informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Table 1.

Correlation between miR-32 expression and different clinicopathological features in oral squamous cell carcinoma.

| Clinicopathological features | No. of cases | miR-32 expression | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High (n, %) | Low (n, %) | |||

| Age | ||||

| <60 | 50 | 28 (56.0%) | 22 (44.0%) | 0.338 |

| ≥60 | 59 | 27 (44.8%) | 32 (55.2%) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 80 | 43 (53.8%) | 37 (46.2%) | 0.284 |

| Female | 29 | 12 (41.4%) | 17 (58.6%) | |

| Histology/differentiation | ||||

| Well + moderate | 75 | 34 (46.6%) | 39 (53.4%) | 0.310 |

| Poor | 34 | 21 (58.3%) | 15 (41.7%) | |

| T classification | ||||

| T1 + T2 | 43 | 30 (69.8%) | 13 (30.2%) | 0.002 |

| T3 + T4 | 66 | 25 (37.9%) | 41 (62.1%) | |

| N classification | ||||

| Positive | 42 | 14 (33.3%) | 28 (66.7%) | 0.006 |

| Negative | 67 | 41 (61.2%) | 26 (38.8%) | |

| TNM stage | ||||

| I + II | 33 | 24 (72.7%) | 9 (27.3%) | 0.003 |

| III + IV | 76 | 31 (40.8%) | 45 (59.2%) | |

Cell lines and miR transfection

Four human OSCC cell lines (SCC-4, SCC-9, SCC-25, and Tca8113) and a human normal oral keratinocyte cell line (hNOK) were obtained from the Beijing Institute for Cancer Research (Beijing, China) and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, CA), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 ug/mL streptomycin. All the cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

For RNA transfection, the cells were seeded into each well of a 24-well plate and incubated overnight, then transfected with mature miR-32 mimics, miR-32 inhibitors (Anti-miR-32), or negative control (miR-NC or anti-miR-NC) (GenePharma, Shanghai, China) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, California, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen Corp, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription reaction was carried out starting from 100 ng of total RNA using the looped primers. Real-time PCR was performed using the standard TaqMan MicroRNA assays protocol on ABI7500 real-time PCR detection system with cycling conditions of 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 74°C for 5 s. U6 small nuclear RNA was used as an internal control. The threshold cycle (Ct) was defined as the fractional cycle number at which the fluorescence passed the fixed threshold. Each sample was measured in triplicate, and the relative amount of miR-32 to U6 was calculated using the equation 2−ΔCt, where ΔCT=(CTmiR-32 − CTU6).

MTT assay

After transfection, OSCC cells were harvested, seeded into 96-well culture plates at a density of 2000 cells in 200 uL/well, and incubated at 37°C. At different time points (24, 48, 72, or 96 h), 100 uL of MTT solution (0.5 mg/mL; Sigma, USA) was added to each well, and the plates were incubated for another 4 h. Then, the MTT solution was removed and 150 uL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to each well to stop the reaction. The plates were gently shaken on a swing bed for 10 min, and spectrometric absorbance at 490 nm was measured using a microplate reader. This experiment was run in triplicate for each sample.

Detection of apoptosis by flow cytometry

Apoptosis was detected by flow cytometric analysis. Briefly, the cells were washed and resuspended at a concentration of 1×106 cells/mL. Then, the cells were stained with Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI), using the Annexin V apoptosis detection kit. After incubation at room temperature in the dark for 15 min, the cell apoptosis was analyzed on a FACSCalibur (Becton, Dickinson and Company, San Jose, CA, USA).

Transwell invasion assay

The invasion assay was performed using 24-well transwell chambers (8 μm; Corning). After transfection, tumor cells were resuspended in serum-free DMEM medium and 2×105 cells were seeded into the upper chambers covered with 1 mg/ml matrigel. We added 0.5 mL DMEM containing 10% FBS to the bottom chambers. Following a 24-h incubation, cells on the upper surface of the membrane were scrubbed off, and the invaded cells were fixed with 95% ethanol, stained with 0.1% crystal violet, and counted under a light microscope.

Scratch migration assay

Scratch migration assay was performed to observe the influence of miR-32 on OSCC cell migration. When the cells transfected with miR-32 mimics, miR-32 inhibitors, or NC were grown to confluence, a scratch in the cell monolayer was made with a cell scratch spatula. After the cells were incubated under standard conditions for 24 h, pictures of the scratches were taken by using a digital camera system coupled with a microscope.

Luciferase reporter assays

The pGL3-report luciferase vector was used for the construction of the pGL3-EZH2 or pGL3-EZH2-mut vectors. The pGL3-EZH2-mut vector was built with EZH2 that had undergone site-directed mutagenesis of the miR-32 target site using the Stratagene Quik-Change site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, Germany). For the luciferase reporter assay, cells were cultured in 24-well plates, transfected with the plasmids and miR-32 mimics using Lipofectamine 2000. Luciferase activity was measured using the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) 24 h after transfection. Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to renilla luciferase activity for each transfected well.

Western blot analysis

Protein lysates were separated by 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to the nitrocellulose membrane. After blocking, the membranes were incubated with purified rabbit anti-EZH2 antisera at 4°C overnight. The next day, the membranes were washed with PBS and then incubated with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG. Immunodetection was conducted with chemiluminescence (ECL) reagents (Pierce) and exposed on an X-ray film. β-actin was used as an internal reference for relative quantification.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were carried out using the SPSS 16.0 software package (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation. Differences between groups were analyzed using the Student’s t-test or chi-square test. Relationships between miR-32 expression and EZH2 protein levels were explored by Pearson correlation analysis. Survival curves were constructed with the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by log-rank tests. To evaluate independent prognostic factors associated with survival, a multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used. P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Decreased expression of miR-32 in OSCC and its correlation with EZH2 levels

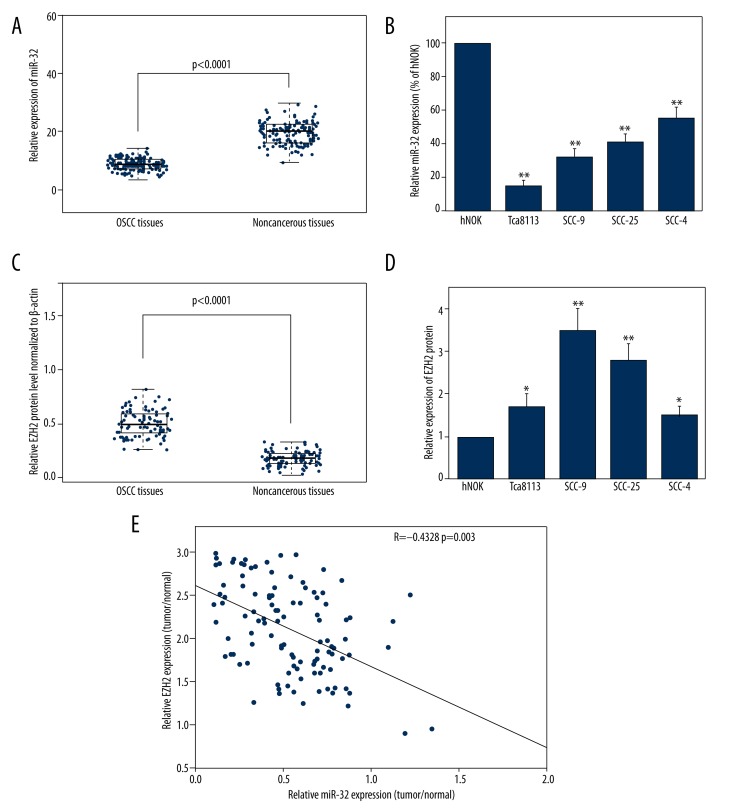

The expression levels of miR-32 in OSCC tissues and cell lines were detected by qRT-PCR and normalized to U6 small nuclear RNA. As in Figure 1A, the results showed that the expression levels of miR-32 were significantly lower in OSCC specimens (mean ±SD: 9.4±1.9) than those in the corresponding adjacent non-cancerous tissues (mean ±SD: 19.9±4.3; P<0.001). The miR-32 expression in 4 OSCC cell lines was also clearly downregulated (Figure 1B). Because Tca8113 cells exhibited the lowest miR-32 expression and SCC-4 cells expressed relatively high levels of miR-32 among the 4 OSCC cell lines, these 2 cell lines were selected for mature miR-32 mimics or miR-32 inhibitors transfection and further studies.

Figure 1.

Expression of miR-32 and EZH2 in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) tissues and cell lines. (A) MiR-32 expression was significantly lower in OSCC tissues than in the corresponding non-cancerous tissues. MiR-32 expression levels were calculated by the 2−ΔCt method and normalized to U6 small nuclear RNA. (B) miR-32 expression was down-regulated in OSCC cell lines SCC-4, SCC-9, SCC-25, and Tca8113, compared to human normal oral keratinocyte cells. * p<0.05; ** p<0.01. (C) Relative EZH2 protein levels in OSCC and corresponding non-cancerous tissues. EZH2 protein levels were measured by Western blot analysis and normalized to β-actin. (D) EZH2 protein levels in OSCC cells were higher than in normal lung epithelial cells. (E) The inverse correlation of EZH2 protein levels with miR-32 expression was examined by Pearson correlation analysis.

EZH2 protein levels were detected by using Western blot analysis in clinical specimens and cell lines. The results showed that EZH2 protein levels in tumor samples were higher than in the adjacent normal tissues (P<0.001; Figure 1C). EZH2 levels in OSCC cells were also higher than in normal oral keratinocyte cells (Figure 1D). In addition, we found an obvious inverse correlation (R=−0.4328, P=0.0003) between EZH2 levels and miR-32 expression in OSCC tumor tissues (Figure 1E).

Association of miR-32 expression with clinicopathological features and patient survival in OSCC

Using the median miR-32 expression in all 109 OSCC patients as a cutoff, the patients were divided into a high miR-32 expression group and a low miR-32 expression group. As shown in Table 1, miR-32 expression level was lower in samples with advanced T classifications (P=0.002), positive N classification (P=0.006), and later TNM stage (P=0.003). No significant difference was observed between miR-32 expression and patient age, gender, or tumor differentiation.

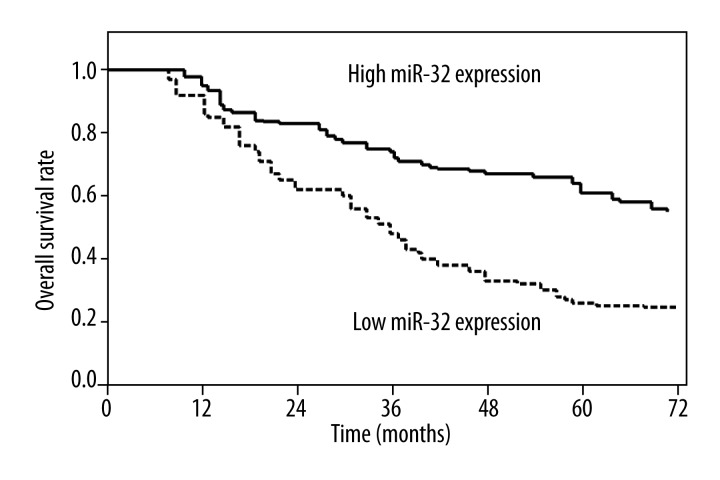

Kaplan-Meier analysis indicated that the survival rate of patients with high miRNA-32 expression was higher than that of patients with low miRNA-32 expression (P<0.001; Figure 2). Survival benefits were also found in those with early T classification (P=0.011), negative N classification (P=0.006), and early TNM stage (P<0.001; Table 2).

Figure 2.

Overall survival curves for 2 groups defined by low and high expression of miR-32 in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Low miR-32 expression levels were significantly associated with poor outcome (P<0.001, log-rank test).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of overall survival in 109 patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma.

| Variables | Univariate log-rank test (p) | Cox multivariable analysis (P) | Relative risk (RR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (years) | |||

| <60 vs. ≥60 | 0.35 | — | — |

| Gender | |||

| Male vs. female | 0.42 | — | — |

| Histology/differentiation | |||

| (Well + moderate) vs. poor | 0.29 | — | — |

| T classification | |||

| T1–2 vs. T3–4 | 0.011 | 0.086 | 0.872 |

| N classification | |||

| Positive vs. negative | 0.006 | 0.019 | 4.655 |

| TNM stage | |||

| I–II vs. III–IV | < 0.001 | 0.005 | 8.245 |

| MiR-32 expression | |||

| High vs. low | < 0.001 | 0.008 | 6.793 |

Multivariate Cox regression analysis enrolling the above-mentioned significant parameters revealed that miR-32 expression (relative risk [RR] 6.793; P=0.008), lymph node metastasis (RR 4.655; P=0.019), and TNM stage (RR 8.245; P=0.005) were independent prognostic markers for overall survival of OSCC patients (Table 2).

Effects of miR-32 on the biological behaviors of OSCC cells

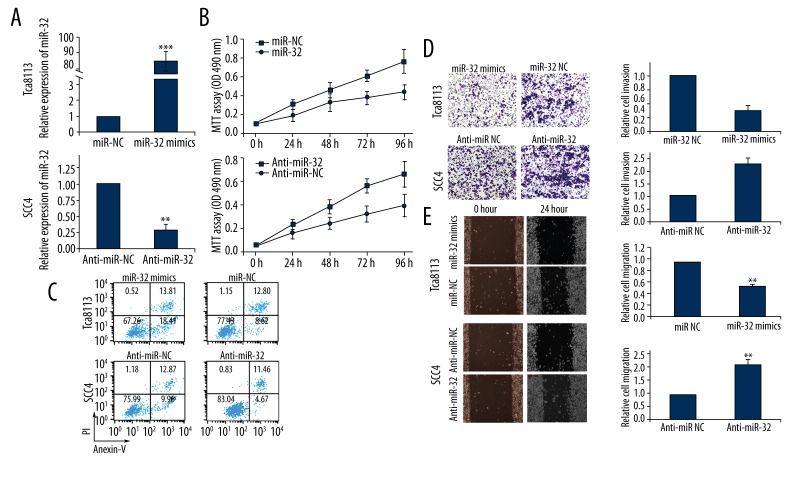

To selectively over-express or down-regulate miR-32, mature miR-32 mimics or miR-32 inhibitors were transfected into Tca8113 or SCC-4 cells. qRT-PCR analysis confirmed increased miR-32 expression after miR-32 mimics transfection and decreased miR-32 expression following miR-32 inhibitors transfection (Figure 3A). MTT assay showed that cell proliferation was significantly impaired in Tca8113 cells transfected with miR-32 mimics, while proliferation of SCC-4 cells was increased in miR-32 inhibitors transfected cells compared with controls (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Effects of miR-32 mimics or inhibitors transfection on biological behaviors of Tca8113 and SCC-4 cells. (A) qRT-PCR analysis confirmed increased miR-32 expression in Tca8113 cells transfected with miR-32 mimics, and decreased miR-32 expression in SCC-4 cells transfected with miR-32 inhibitors. U6 RNA was used as an internal control. (B) MTT assay showed that miR-32 reduced cell proliferation in vitro. Data represent the mean ±SD of the experiments performed in triplicate. ** p<0.01. (C) Cell apoptosis was detected by flow cytometric analysis after transfection with miR-32 mimics, miR-32 inhibitors, or negative control. (D) Transwell invasion assay showed that up-regulation of miR-32 impeded the invasion of Tca8113 cells, while transfection of SCC-4 cells with miR-32 inhibitors promoted cell invasion. (E) Scratch migration assay confirmed the inhibitory effect of miR-32 on OSCC cell migration. ** p<0.01.

Flow cytometry was employed to determine the effect of miR-32 on cell apoptosis. The proportion of apoptotic Tca8113 cells transfected with miR-32 mimics was significantly higher than the negative control group. Moreover, down-regulation of miR-32 reduced SCC-4 cell apoptosis (Figure 3C).

Transwell invasion assay was performed to investigate whether miR-32 had a direct influence on OSCC cell invasion. As shown in Figure 3D, up-regulation of miR-32 impeded the invasion of Tca8113 cells compared with control. Conversely, transfection of SCC-4 cells with miR-32 inhibitors promoted cell invasion ability. Scratch migration assay also confirmed the inhibitory effect of miR-32 on OSCC cell migration (Figure 3E).

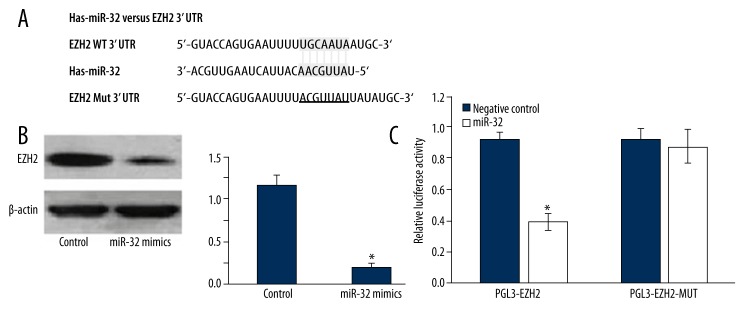

EZH2 is a target gene of miR-32

Using the bioinformatics software TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org) for target gene prediction, EZH2 was identified as 1 of the potential targets of miR-32. The predicted binding of miR-32 with EZH2 3′UTR is illustrated in Figure 4A. To further confirm that EZH2 is the direct target of miR-32 in OSCC, we first transfected miR-32 mimics into Tca8113 cells and found that miR-32 mimics significantly reduced EZH2 protein levels in these cells (Figure 4B). Then, we created pGL3-EZH2 and pGL3-EZH2-mut plasmids. Reporter assay revealed that transfection of miR-32 mimics triggered a marked decrease of luciferase activity of pGL3-EZH2 plasmid in Tca8113 cells, without change in luciferase activity of pGL3-EZH2-mut (Figure 4C). These data indicate that EZH2 is a direct target of miR-32 in OSCC.

Figure 4.

EZH2 is a direct target of miR-32. (A) miR-32-binding sites in EZH2 3′UTR region. EZH2-mut indicates the EZH2 3′UTR with mutation in miR-32-binding sites. (B) Western blot showed that transfection of miR-32 decreased EZH2 protein expression. (C) Relative luciferase assay comparing the pGL3-EZH2 and pGL3-EZH2-MUT vectors in Tca8113 cells. Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla luciferase activity. * p<0.05.

Discussion

Dysregulation of miRs has been demonstrated to be involved in tumorigenesis and progression in various types of tumors; however, elucidation of their potential roles in OSCC remains in the early stage. In the present study, the potential relationship between miR-32 expression level and various clinicopathological factors and postoperative survival time were analyzed. We confirmed miR-32 downregulation in OSCC tumor samples and its correlation with advanced tumor stage, lymph node involvement, and shorter overall survival. Multivariate Cox hazard regression analysis identified low miR-32 expression as an indicator of unfavorable prognosis independent of other clinicopathological factors. In vitro functional assays demonstrated that modulation of miR-32 expression affected OSCC cell proliferation, apoptosis, invasion, and migration. These findings indicate that miR-32 may participate in regulating the initiation and development of OSCC, and could be useful as a diagnostic/prognostic biomarker and serve as a novel target for the gene therapy of OSCC. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to analyze the clinical significance and biological function of miR-32 in OSCC.

MiR-32, located on chromosome band Xq26.2, has been shown to have tumor-suppressor functions in human osteosarcoma and gastric cancer. Xu et al. found that miR-32 was significantly down-regulated in osteosarcoma tissues, compared with the adjacent normal tissues. In vitro studies demonstrated that miR-32 mimics were able to suppress, while its antisense oligonucleotides promoted, the proliferation and invasion of Saos-2 and U2OS osteosarcoma cells [13]. Zhang et al. revealed that up-regulation of miR-32 significantly inhibited the proliferation and decreased the migration and invasion capabilities of SGC7901 gastric cancer cells.

In contrast to the antitumor properties mentioned above, miR-32 also acts as an oncogene in several cancers. MiR-32 overexpression in colorectal carcinoma cells enhanced cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, and reduced cell apoptosis [8]. High miR-32 levels in colorectal carcinoma patients were significantly associated with lymph node and distant metastasis, and poor overall survival [20]. Increased miR-32 expression has also been reported in kidney cancer and prostate cancer [9,21], and miR-32 was shown to be androgen-regulated and overexpressed in castration-resistant prostate cancer [22]. In addition, pretreatment with anti–miR-32 oligonucleotides sensitized acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) cells to arabinocytosine, a chemotherapeutic drug used to treat human AML, via induction of cell apoptosis [23]. Taken together, the role of miR-32 in human malignancies may be multifaceted, depending on the involved tissue.

It is now clear that miRs execute their oncogenic or tumor suppressor functions by regulating the expression of target genes [24]. With regard to miR-32, several targets have been confirmed in recent research, including B-cell translocation gene 2 (BTG2) [22], sex-determining region Y-box 9 protein (SOX9) [13], phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) [8], and tumor necrosis factor-receptor-associated factor (TRAF) [25]. EZH2, as a tumor-promoting gene, has been found to be upregulated in different tumor types, and was identified as a target gene of a number of miRs. Kidani et al. corroborated high EZH2 expression in OSCC tumor tissues and cell lines [16]. Further analysis indicated that up-regulation of EZH2 was significantly correlated with advanced tumor stage and shorter survival time. Zhao et al. found that knock-down of EZH2 could decrease the proliferation ability, induce apoptosis, and inhibit the migration of OSCC cells [26]. Using luciferase reporter assay, our study demonstrated that EZH2 was a direct target of miR-32 in OSCC. However, there is no ‘one-to-one’ connection between miRs and target mRNAs. An average miR can have more than 100 targets [27]. Conversely, several miRs can converge on a single transcript target [28]. EZH2 is not the only miR-32 target dysregulated in OSCC. Other functional targets of miR-32 such as PTEN and SOX9 [29,30] also modulate OSCC pathogenesis. Therefore, the potential regulatory circuitry afforded by miR-32 is enormous, and the exact mechanisms by which miR-32 influences OSCC progression need further clarification.

Conclusions

MiR-32, down-regulated in OSCC, functions as a tumor suppressor, and EZH2 is one of its downstream target genes. This finding helps us understand the molecular mechanism of carcinogenesis and also gives us a strong rationale to further investigate miR-32 as a potential treatment target for OSCC.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors had no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to this article.

Source of support: Departmental sources

References

- 1.Sharma P, Saxena S, Aggarwal P. Trends in the epidemiology of oral squamous cell carcinoma in Western UP: an institutional study. Indian J Dent Res. 2010;21:316–19. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.70782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Massano J, Regateiro FS, Januario G, Ferreira A. Oral squamous cell carcinoma: review of prognostic and predictive factors. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;102:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heneghan HM, Miller N, Kerin MJ. MiRNAs as biomarkers and therapeutic targets in cancer. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10:543–50. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang H, Qi F, Cao Y, et al. Down-regulated microRNA-101 in bladder transitional cell carcinoma is associated with poor prognosis. Med Sci Monit. 2014;20:812–17. doi: 10.12659/MSM.890300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Y, Zhao J, Zhang PY, et al. MicroRNA-10b targets E-cadherin and modulates breast cancer metastasis. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18(8):BR299–308. doi: 10.12659/MSM.883262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shang C, Lu YM, Meng LR. MicroRNA-125b down-regulation mediates endometrial cancer invasion by targeting ERBB2. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18(4):BR149–55. doi: 10.12659/MSM.882617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu W, Yang J, Feng X, et al. MicroRNA-32 (miR-32) regulates phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) expression and promotes growth, migration, and invasion in colorectal carcinoma cells. Mol Cancer. 2013;12:30. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petillo D, Kort EJ, Anema J, et al. MicroRNA profiling of human kidney cancer subtypes. Int J Oncol. 2009;35:109–14. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ambs S, Prueitt RL, Yi M, et al. Genomic profiling of microRNA and messenger RNA reveals deregulated microRNA expression in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6162–70. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pichiorri F, Suh SS, Ladetto M, et al. MicroRNAs regulate critical genes associated with multiple myeloma pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:12885–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806202105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J, Kuai X, Song M, et al. microRNA-32 inhibits the proliferation and invasion of the SGC-7901 gastric cancer cell line. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:270–74. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu JQ, Zhang WB, Wan R, Yang YQ. MicroRNA-32 inhibits osteosarcoma cell proliferation and invasion by targeting Sox9. Tumour Biol. 2014;35(10):9847–53. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2229-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahmoudi T, Verrijzer CP. Chromatin silencing and activation by Polycomb and trithorax group proteins. Oncogene. 2001;20:3055–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simon JA, Lange CA. Roles of the EZH2 histone methyltransferase in cancer epigenetics. Mutat Res. 2008;647:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kidani K, Osaki M, Tamura T, et al. High expression of EZH2 is associated with tumor proliferation and prognosis in human oral squamous cell carcinomas. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu L, Guo J, Yu L, et al. miR-101 regulates expression of EZH2 and contributes to progression of and cisplatin resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer. Tumour Biol. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2585-6. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo Y, Ying L, Tian Y, et al. miR-144 downregulation increases bladder cancer cell proliferation by targeting EZH2 and regulating Wnt signaling. Febs J. 2013;280:4531–38. doi: 10.1111/febs.12417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tao T, Liu D, Liu C, et al. Autoregulatory feedback loop of EZH2/miR-200c/E2F3 as a driving force for prostate cancer development. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1839:858–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu W, Yang P, Feng X, et al. The relationship between and clinical significance of MicroRNA-32 and phosphatase and tensin homologue expression in colorectal cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2013;52:1133–40. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leite KR, Tomiyama A, Reis ST, et al. MicroRNA expression profiles in the progression of prostate cancer – from high-grade prostate intraepithelial neoplasia to metastasis. Urol Oncol. 2013;31:796–801. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jalava SE, Urbanucci A, Latonen L, et al. Androgen-regulated miR-32 targets BTG2 and is overexpressed in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2012;31:4460–71. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gocek E, Wang X, Liu X, et al. MicroRNA-32 upregulation by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in human myeloid leukemia cells leads to Bim targeting and inhibition of AraC-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6230–29. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu GF, Tang D, Li P, et al. S-1-based combination therapy S-1 monotherapy in advanced gastric cancer: A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:310–18. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i1.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mishra R, Chhatbar C, Singh SK. HIV-1 Tat C-mediated regulation of tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor-3 by microRNA 32 in human microglia. J Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:131. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao L, Yu Y, Wu J, et al. Role of EZH2 in oral squamous cell carcinoma carcinogenesis. Gene. 2014;537:197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brennecke J, Stark A, Russell RB, Cohen SM. Principles of microRNA-target recognition. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e85. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krek A, Grun D, Poy MN, et al. Combinatorial microRNA target predictions. Nat Genet. 2005;37:495–500. doi: 10.1038/ng1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Squarize CH, Castilho RM, Santos Pinto D., Jr Immunohistochemical evidence of PTEN in oral squamous cell carcinoma and its correlation with the histological malignancy grading system. J Oral Pathol Med. 2002;31:379–84. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2002.00142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Misuno K, Liu X, Feng S, Hu S. Quantitative proteomic analysis of sphere-forming stem-like oral cancer cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2013;4:156. doi: 10.1186/scrt386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]