Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to explore health care providers’ (HCPs) attitudes and beliefs about adolescent sexual health care provision in the emergency department (ED) and to identify barriers to a role of a health educator-based intervention.

Methods

We conducted focused, semi-structured interviews of HCPs from the ED and Adolescent Clinic of a children’s hospital. The interview guide was based on the Theory of Planned Behavior and its constructs: attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and intention to facilitate care. We used purposive sampling and enrollment continued until themes were saturated. Interviews were recorded and transcribed. Transcripts were analyzed using directed content analysis.

Results

Twenty-nine interviews were required for saturation. Participants were 12 physicians, 12 nurses, 3 nurse practitioners and 2 social workers; the majority (83%) were female. Intention to facilitate care was influenced by HCP perception of 1) their professional role, 2) the role of the ED (focused vs. expanded care), and 3) need for patient safety. HCPs identified three practice referents: patients/families, peers and administrators, and professional organizations. HCPs perceived limited behavioral control over care delivery because of time constraints, confidentiality issues, and comfort level. There was overall support for a health educator and many felt the educator could help overcome barriers to care.

Conclusion

Despite challenges unique to the ED, HCPs were supportive of the intervention and perceived the health educator as a resource to improve adolescent care and services. Future research should evaluate efficacy and costs of a health educator in this setting.

Adolescents in the U.S. face many barriers to sexual health care, including lack of access, concerns about privacy, transportation, cost, and lack of provider knowledge.1, 2 These barriers contribute to the sexual health challenges facing adolescents, including high rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and unintended pregnancy.3, 4 Adolescents may not receive needed health services, with nearly 1 in 5 reporting decisions to forgo health care. 5 Adolescents comprise 15% of all ED visits and frequently seek care for non-urgent complaints.6 The prevalence of high-risk sexual health behaviors is high among adolescent ED users.7–10 Thus, EDs may provide a unique opportunity to provide sexual health interventions to a high risk population that is difficult to reach in traditional primary care settings.

Developing interventions to improve adolescent access to sexual health care has the potential to impact public health and is consistent with the goals of Healthy People 2020.11 In fact, ED-based adolescent interventions have been successfully implemented for a variety of concerns including HIV screening, mental health, injury prevention, and substance abuse.12–14 We propose the inclusion of a health educator, a new member of the ED team, whose role is to provide focused sexual health care to adolescent patients. Provided in addition to the visit-related care given by other members of the ED team, this care could include testing for STIs and pregnancy, risk reduction education, evaluating for emergency contraception, and/or referral to the hospital-based adolescent clinic for comprehensive care (e.g., sexual identity counseling, long-acting reversible contraception). The health educator would work as part of the ED team but would not be responsible for providing services considered to be outside the described role.

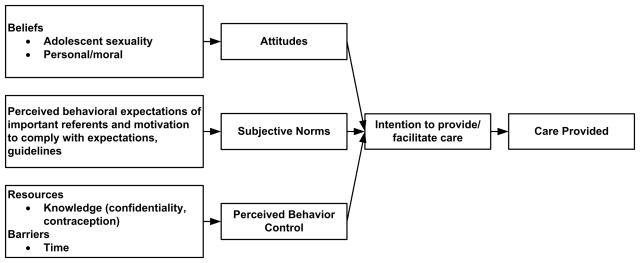

Implementing new interventions within an existing health care system is a complex and challenging process and understanding the perspectives of health care providers (HCPs) is essential to success. The theory of planned behavior (TPB) states that an individual’s attitudes, subjective norms (opinions of significant peers and professional organizations), and perceived behavioral control, all influence the intention to act in a specific way. Intention, in turn, influences actual behavior (Figure 1).15 The TPB has previously been used to explore HCP medication selection and health counseling provision, among other topics. 16,17 We used this model to provide structure for the design and implementation of an proposed intervention, as well as an analytic pathway for evaluation.

Figure 1.

Modified Theory of Planned Behavior, adapted to model provision or facilitation of sexual health care for adolescents

The aim of this study was to use the TPB framework 1) to explore the attitudes and beliefs of HCPs about their intention to facilitate or provide adolescent sexual health care, and 2) to identify HCPs’ perspectives on barriers to care. We explored specific attitudes about a proposed intervention to add a health educator to the ED team, as part of a larger goal to improve teen access to targeted, as well as comprehensive, sexual health care.

METHODS

We conducted focused, semi-structured interviews with HCPs from an urban, academic children’s hospital. The study protocol and consent procedures (including waiver of written consent) were approved by the university institutional review board.

Population and Study Setting

The purpose of this study was to understand HCPs intentions to provide and support adolescent sexual health innovations in care delivery and to anticipate process issues that could affect future implementation of a proposed intervention. The intervention had the potential to impact two work settings, both the ED where the initial intervention would occur, and the adolescent clinic where adolescents might be referred for follow up. Stakeholders with various roles in emergency and adolescent health provision, including nurses, nurse practitioners (NPs), physicians, and social workers were included from both settings. Except for pediatric emergency medicine fellows, HCPs in training were excluded.

We conducted this study at a Midwestern, free-standing, urban children’s hospital system. The ED has approximately 70,000 visits each year and is a level one trauma center that is staffed primarily by at least one pediatrician fellowship-trained in pediatric emergency medicine (or currently in fellowship). A few providers completed emergency medicine residency, and one completed PEM fellowship after residency. The NPs care for patients independently and nurses specialize in pediatric acute care. The adolescent clinic has approximately 11,600 annual visits. The clinic is located in a separate free-standing building and is staffed by adolescent fellowship-trained physicians as well as general pediatricians, NPs, and nurses with specialized training in adolescent health. In both settings, the majority of patients are non-white and have government-issued insurance. Social workers are available at all times in the ED and during hours of operation in the adolescent clinic.

Participants were recruited by email, word of mouth, and phone contacts. We utilized purposive sampling techniques by recruiting participants who exhibited extremes of experience and opinion in the key stakeholder positions. Snowball sampling allowed participants to refer other HCPs to the study team. Interested participants contacted the study research assistant, who determined eligibility for the study and arranged interviews at a mutually convenient time.

Thirty interviews were conducted; during one interview, the tape-recorder malfunctioned and data were lost, leaving 29 usable transcripts. Participants included: 12 physicians (ED 10, Adolescent Clinic 2); 12 nurses (ED 10, Adolescent Clinic 2); 3 NPs (all from ED); and 2 social workers (ED 1, Adolescent Clinic 1). Three ED physicians were fellows and at least one physician and one nurse administrator participated from each setting. Five participants were male and all were physicians. Overall, there was a wide range of clinical experience among physicians (4–25 years; mean 10.5), nurses (1.5–30 years; mean 9), and NPs (8–10 years; mean 8.7). Similar percentages of eligible nurses (ED 13%, Adolescent Clinic 27%) and physicians (ED 25%, Adolescent Clinic 25%) participated from each setting.

Interview Guide Development and Data Collection

A detailed interview guide, based on the TPB, was developed by a multidisciplinary team with varied opinions about sexual health care provision and expertise in pediatric emergency medicine, adolescent psychology and health, health services research, nursing, and qualitative methods. The interview guide was designed to explore the participant’s perceptions of each TPB construct, including attitudes about adolescent sexual health care, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and intention. Additionally, participants were asked their opinions about a proposed intervention with an ED health educator. Primary questions from the interview guide are listed in Table 1, and probes were used to garner more detail and examples from providers’ experience.

Table 1.

Primary questions from the interview guide

| Topic Assessment | Question |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Attitude | Is access to sexual health care an important issue for adolescents? |

| What is the role of health care providers in the ED in improving adolescent sexual health? | |

| What is the role of health care providers in the ED in identifying STIs and pregnancy among adolescents? | |

| What role, if any, do health care providers have in preventing STIs and unintended pregnancy among adolescents? | |

|

| |

| Subjective norms | Are there any professional organizations that influence your practice? |

| Who are the people that influence how you take care of patients? | |

|

| |

| Perceived behavior control | What are the barriers to screening asymptomatic adolescents for STIs and pregnancy in the ED? |

| Can you think of any ways to overcome these barriers? | |

| If a teen-aged girl were in the ED because she hurt her leg, how would you feel if someone came to talk to her about her sexual health? | |

|

| |

| Intention to facilitate care | How would you feel about another provider (such as a health educator) providing this type of sexual health care in the ED? |

| Would you be comfortable addressing certain health concerns that might come up but go beyond the expertise of the health educator, such as disclosure of sexual abuse? | |

| We are considering the development of a new position, like a health educator, to provide expanded sexual health care for teens. Health educators will obtain urine for testing for STIs and pregnancy, and will provide brief education as well as a link to comprehensive care. First, tell me what you think of that? | |

|

| |

| Intervention Specific | If the health educator finds a positive pregnancy test for a teen in the ED, what kind of process can you see for handling the results? |

| Is there a situation in which this intervention couldn’t be done? What would that be? | |

Interviewer training consisted of multiple meetings to develop and discuss the interview guide, and mock interviews with direct feedback from an experienced investigator (KG). Two study personnel (RO and GM, both doctoral students in psychology) conducted the sessions in a private office. The interviews lasted between 11 and 35 minutes (mean 20.4 minutes). All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Interviews were conducted during November 2011 through January 2012.

Data Analysis

Transcripts were entered into NVIVO 9 software (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia) and included demographic data to allow for subgroup analyses. Throughout data collection, the team met biweekly to discuss interview progress, recruitment, and quality control issues. After 30 interviews, there was consensus among the research team about the repetition of themes and the achievement of data saturation. After interviews were complete, the five member research team (including GM and RO, who conducted the interviews) analyzed the data using directed content analysis. 18

Raw data were initially organized into discrete categories based on the constructs of the TPB that were then reviewed independently by the team members for the emergence of themes. The lead investigator reviewed and summarized the themes identified by each team member, and the study team discussed each theme and identified representative, illustrative quotes. Discrepancies around theme development were resolved by consensus, with notes maintained about all discrepancies and decisions. The interviewers provided additional information, such as tone, that may be difficult to ascertain from a transcript. Data were also contrasted across occupation to examine these as potential mediators of responses.

RESULTS

Overall, participants expressed a wide variety of opinions and many felt strongly about their views. Many expressed confidence that their knowledge or opinion of consent laws were correct even though their response was not accurate. There was little variation in responses by occupation except, notably, for support of the intervention.

Attitudes about Sexual Health Specifics

Many HCPs identified patient safety as a concern, especially around issues of confidentiality and potential sexual abuse or coercion (Table 2 provides quotes related to attitudes). Providing a safe, comfortable environment, as well as sexual health education for teens, was also identified as important. The importance of providing accurate and complete information in order to make “sure that things are clear, that their choices are clear” regarding sexual health was also valued by participants.

Table 2.

Participant Quotes Within the Attitude Construct

| Theme | Illustrative Quotes | Provider |

|---|---|---|

| Patient safety and health is important | “That may be the only avenue that young person knows how to access healthcare or may be their only choice in accessing healthcare. So, it may be the one shot that we have of decreasing STD transmission, and getting somebody into either prenatal care early, or for an abortion early on, so that there is a choice for that person.” | Adolescent clinic physician |

| “If they’re worried about being put in this situation where they’re going to be physically harmed, if not by the parent, but the partner…It all hinges on safety, confidentiality and safety, and if we can ensure those things.” | ED physician | |

| “I think with the younger ones, they’re coerced more than older individuals, so I think that needs to be in the education too.” | ED nurse practitioner | |

| HCPs divided on professional role and role of the ED | “I think that we should be screening for those by asking whether…people are sexually active or not. If they are …then screen them by asking questions, and if they show any symptoms, we should be testing them.” | ED nurse |

| “We’re the first line of healthcare, so our role is very important in identifying and treating pregnancy and STDs in adolescents.” | ED nurse | |

| “I definitely think that it’s our role to think of it [sexual health] in every patient, but especially those who come in with complaints that might be related to either one of those problems.” | ED physician | |

| “Do we have a role in examining for sexual health and pregnancy problems that are neither directly or indirectly related to the health care visit to the emergency department is something that I don’t know if I’m decided about.” | ED physician | |

| “I think it gets trickier once you talk about screening of an asymptomatic patient, particularly because I worry about the follow-up. That’s something that’s probably best followed within a clinic structure where follow-up care is possibly more available.” | Adolescent clinic physician |

Participants were divided regarding the role of HCPs in identifying specific sexual health issues (such as STIs and pregnancy) in the ED. Many HCPs felt all teens should be asked about sexual health behaviors, regardless of their chief complaint during an ED visit; further evaluation should be provided as indicated. Several providers expressed that teens are a vulnerable group who may face unique barriers when obtaining care. Many considered diagnosing pregnancy particularly important “because of potential risks to the fetus.” A vocal minority felt their role was related to presenting complaints and that “more focused care” was appropriate.

When asked specifically about STI and pregnancy prevention in the ED, there were mixed opinions. While many felt providing education was important, there was disagreement as to whether education should be directed to all teens or those with reproductive complaints. Most felt that identification and treatment of sexual health conditions would be the same regardless of patient age but many acknowledged that maturity and receptivity to care varies greatly.

Several HCPs suggested an undercurrent of negativity towards adolescents and commented about colleagues who make judgments about adolescents or who “don’t want to deal with teenagers at all.” A few providers also felt that lack of honesty from adolescents or body language, such as “slouching in the chair” has an impact on communication and care delivery. In addition, if an adolescent perceives that a HCP is uncomfortable or judgmental, they may be less likely to engage in an honest dialogue about sex.

Subjective Norms about Adolescent Sexual Health Care

HCPs identified several referents that influenced their health care practice, without strong consensus: peers/administrators (identified by 23 participants), and professional organizations (20 participants), and patients/families (11 participants) (Table 3 provides quotes on subjective norms). Nurses most frequently listed peers/administrators and patients/families as influences and physicians most frequently listed professional organizations and peers/administrators. When not identifying a specific referent, ten participants instead reported that past experiences (e.g., religious upbringing or specific training) influenced their practice. Several participants displayed low motivation to comply with treatment guidelines such as those provided by national medical organizations or in academic journals, stating they cautiously interpreted research or took “everything…with a grain of salt”. In addition, five participants reported they were influenced by no one in particular.

Table 3.

Participant Quotes Within the Subjective Norms and Perceived Behavioral Control Constructs

| Construct | Theme | Illustrative Quotes | Provider |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective norms | Wide variety of influences | “Professionally, we do have evidence practice guidelines we follow for disease management prevention, but also I do rely upon my own personal faith in how I would manage patients.” | ED nurse practitioner |

| “My coworkers, my family, my friends, my children…I take influences from everybody I come in contact with.” | ED nurse | ||

| “You’re influenced by the system you work in, and the policy and procedures that are in place there. You’re influenced greatly by the patients themselves.” | Adolescent clinic physician | ||

| “I don’t think there’s anybody that influences me. I kind of have my own way.” | ED nurse | ||

| Perceived behavioral control | Time constraints | “I think if you’re going to have a discussion with an adolescent about sexual behavior that is going to be meaningful, it takes a little while.” | ED physician |

| “That [sexual health care] should be done in a primary care office. They have time to talk with the patient, they have time to develop a relationship, which is key for sexual problems, and we don’t.” | ED physician | ||

| Parental presence is a barrier | “Parents at the bedside can be a barrier. I think it’s difficult for us as nurses, especially when the laws aren’t very clear cut.” | Adolescent clinic nurse | |

| Provider discomfort | “Providers that don’t want to deal with teenagers at all, but particularly on issues relating to below the belt. Reproductive health issues are just not comfortable for a lot of people.” | ED physician | |

| “From talking to female adolescents, they feel uncomfortable, at least that’s my impression, with me [a male] talking about that subject.” | ED physician | ||

| Lack of knowledge | “I don’t think we have all the teaching tools, also. Maybe our knowledge is limited.” | ED nurse practitioner |

Perceived Behavioral Control about Adolescent Sexual Health Care

Most participants identified more than one potential barrier to care (Table 3 provides quotes for themes described in this section). The most common barrier was time and ED patient flow issues, identified by 21 subjects. Several noted that patient acuity can drive provider availability and that “it only takes one high acuity patient to demand a lot of your time and resources.”

Fourteen participants identified issues around adolescent confidentiality and parental presence as a barrier. Many felt parental presence affects adolescent privacy and “puts a limit on the sort of information we can give them and get from them.” Many providers recognized the importance of a confidential interview; however, they acknowledged that asking parents to step out can be “uncomfortable” and parents may refuse to leave. This barrier may drive some providers to avoid care or to obtain the history with parents at the bedside, which “makes everybody in the room uncomfortable” and may compromise accuracy.

Some participants (N=9) identified provider discomfort as a barrier and suggested that providers may “feel awkward approaching that subject.” Several providers reported that building rapport with an adolescent can be difficult and takes time that is often not available in the ED. Rarely, language differences, gender differences, and religious or cultural beliefs (of participants or of patients/families) were mentioned. For example, one HCP felt “strongly against emergency contraception and abortion” and “could not provide that care” for adolescents.

While some reported sufficient knowledge about emergency contraception, others acknowledged a lack of knowledge about long-term contraception, considering it beyond their “area of expertise.” Several participants had specific knowledge deficits about the legal age for an adolescent to consent to sexual intercourse and/or to receive confidential health care services. One ED nurse was unsure “if we have to tell the parents everything.”

Participants identified several facilitators for sexual health discussion. Some HCPs felt it may be easier to bring up sexual health with adolescents who have reproductive complaints. Some felt the “anonymous” nature of the ED might aid discussion as providers can be “blunt” and teens might feel less “stigma.” Providers had many ideas to overcome barriers, most commonly suggesting parents step out to facilitate privacy. Others suggested a consistent protocol or system would be helpful. Several mentioned a screening process or questionnaire that could inform HCPs so “you’ll know it is a concern for that patient.” A few felt that providing education for HCPs, and also to families and teens, would be helpful. Specific topics included importance of adolescent confidentiality, significance of the problems of STIs and unintended pregnancy among the target population, and care resources.

Intention to Facilitate Adolescent Sexual Health Care in the Emergency Department

There was very strong support for a health educator to provide targeted sexual health care and most intended to facilitate this care by collaborating with the proposed health educator (Table 4 provides illustrative quotes for themes from this section). A minority (6 participants, 5 of whom were ED nurses) did not support the intervention and had concerns, including cost effectiveness, ED flow and additional HCP tasks if the health educator could not “function pretty independently.” Most felt comfortable addressing health concerns that might require expertise beyond that of the health educator, such as prescribing emergency contraception and handling sexual abuse disclosure cases.

Table 4.

Participant Quotes Within the Intention Construct

| Theme | Illustrative Quotes | Provider |

|---|---|---|

| Wide support for health educator | “I think that’s exciting! I love it, I think that’s great! I think that works.” | Social worker |

| “[Teens] are out making these types of decision and aren’t really informed about the possible consequences. Maybe because they don’t go to routine checkups or whatever, sometimes it doesn’t hurt to hear it more than once even if they do go to their regular doctor.” | ED physician | |

| “…sometimes with these adolescents, the ER is the only healthcare they get. So from a public health standpoint, I like it, but I really like that there’s someone else doing it.” | ED physician | |

| Minority not supportive | “I feel that kind of takes away from the idea of the emergency department.” | ED nurse |

| “I have mixed emotions on that one.” | ED nurse |

Attitudes about the Intervention

Two major domains were examined regarding the proposed ED intervention: 1) HCP attitudes about the intervention and 2) perceptions about logistics and implementation.

Many providers thought having a health educator who is comfortable with adolescent health issues would provide more consistent care and would make sexual health care “less threatening.” Others mentioned the health educator could help overcome barriers such as time constraints and HCP discomfort. Several commented that coordination of care with ED staff was important for HCPs to “feel comfortable” with the plan of care and many stressed communication with families and adolescents as another key to success. Many participants felt that providing education and resources to spark “that discussion…just between the parent and the child” were valuable roles for the ED in improving adolescent sexual health. Providers also identified referrals for ongoing care and promotion of safety (e.g., condom distribution) as appropriate ED tasks.

Most felt the exam room was the best place for the intervention and stressed the importance of privacy and patient comfort, including having parents out of the room and making sure the patient was clothed. Several suggested a separate space that “doesn’t seem sterile and medical” might provide comfort. Some recognized the difficulty in finding a place that provides comfort yet does not interrupt ED flow. Most felt the intervention could occur mid-visit, and many felt it was important to address the chief complaint first “so they feel like they’re getting what they came for.” Some suggested a “team approach” and others thought it would be helpful to introduce the idea of assessing for sexual health early in the visit so patients and families would know what to expect.

Most HCPs felt a pregnancy diagnosis should be delivered by a HCP and several felt the ED physician should be involved. Some providers felt that a “joint effort” and “pulling from different disciplines” would be best. Many felt that education, including “options counseling,” as well as a clear system for referral and follow-up were important. The current system for STI test follow-up, where a nurse contacts patients and implements a treatment plan was considered satisfactory by the majority of participants. For both pregnancy and STIs, many participants acknowledged that having someone who has already established a good rapport could be helpful.

DISCUSSION

This study describes the perspectives of key stakeholders likely to be involved in ED-based interventions to improve adolescent sexual health care. Participants expressed an understanding of the impact of sexual health behaviors on multiple health outcomes, but described complex barriers—at both the individual and system levels—to providing this care. Consistent with current literature, we found that limited time and resources as well as inadequate training may discourage physicians from screening for health needs.15, 18, 19 Likewise, examples are found of provider discomfort with sexual health issues, for both general and adolescent populations.18, 20, 21

While limited data supports the use of health educators in the pediatric ED, this research is novel because there is a paucity of information regarding 1) adolescents as the intervention recipients and 2) interventions focused on pregnancy and STI detection and prevention. 12, 24, 25 Several areas were identified that should inform future education efforts. First, while many HCPs advocated for protecting adolescent health and safety, their success may be impaired by knowledge deficits surrounding confidentiality and age of consent for sexual intercourse and medically emancipated conditions. These findings support those of other researchers who have documented pediatric ED provider discomfort and lack of knowledge about legal issues in providing pediatric health care.19, 26 Pediatric HCPs should be familiar with and follow their local laws around providing this care. Also, our findings that some participants do not utilize care guidelines is consistent with current literature indicating that guideline uptake is limited by self-efficacy, awareness, and agreement.27, 28

Many participants expressed strong beliefs, and this was true across several domains. In particular, one participant expressed strong, conservative religious beliefs that informed their approach to care. While it is difficult to estimate the prevalence of such views among HCPs in other pediatric EDs, there is ample evidence of providers’ religious or moral beliefs negatively affecting adolescent sexual health care.1, 26, 29, 30 In addition, negative attitudes about providing adolescent sexual health care have been previously reported among pediatric HCPs, especially surrounding emergency contraception.1, 26, 31 Many studies describe the challenges involved in changing HCP attitudes and behaviors; implementing an innovative intervention such as a sexual health educator provides an alternative strategy to meet adolescent sexual health needs. 27, 32–34

Interestingly, despite some concerns and negative attitudes expressed by participants in our study, most stated that they would support this ED intervention to provide sexual health care. While there was slightly less support for the intervention among ED nurses, there was little variation in opinions overall based on occupation. Although we considered that professional role might influence attitudes, our study findings did not support this.

There are several limitations to consider when interpreting our results, some of which are inherent in qualitative methods.35–36 One limitation is potential participant selection bias, as interest or unknown characteristics may be associated with participation. To reduce this possibility, we used purposive sampling to obtain a diverse group of participants. Also, this study was conducted at a single urban, academic institution, and while underserved, high-risk adolescents may frequent such a setting, our results may not be generalizable to other settings. Also, all of the ED physicians that participated were PEM trained, and there may be different opinions between other types of physicians who provide care in this setting. While the influence of potential bias among the investigators cannot be fully neutralized, we utilized a multidisciplinary team, educated and experienced in the importance of maintaining objectivity in conducting research to minimize this possibility. Researcher triangulation with five study members enhanced credibility of analysis. To minimize possible effects of social desirability and demand bias, the study interviewers were unfamiliar with both working environments and unknown by study participants.

CONCLUSION

Participating HCPs at this urban, academic pediatric hospital were generally supportive of providing opportunities for sexual health care in the ED but voiced specific concerns about time constraints, patient flow, confidentiality, and HCP discomfort. These HCPs perceived the intervention as an innovative way to provide useful services. Future research should evaluate health outcomes and costs of a health educator in this setting.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. M. Denise Dowd, Sharon G. Humiston, and Timothy Apodaca for their contributions to the larger project which also incorporates this study. We thank Tiffany Heffner for her help with participant recruitment.

References

- 1.Miller MK, Dowd MD, Plantz DM, et al. Pediatric Emergency Medicine Health Care Providers’ Knowledge, Attitudes and Experiences Regarding Emergency Contraception. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18(6):605–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hock-Long L, Herceg-Baron R, Cassidy AM, et al. Access to Adolescent Reproductive Health Services: Barriers to Care. Perspec Sexual Repro Health. 2003;35:144–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. [Accessed June 9, 2011];STD Surveillance. 2009 http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats09/tables/10.htm.

- 4.McKay A, Barrett M. Trends in teen pregnancy rates from 1996–2006: a comparison of Canada, Sweden, USA and England/Wales. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality. 2010;19(1–2):43–52. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ford CA, Bearman PS, Moody J. Forgone Health Care Among Adolescents. JAMA. 1999;282(23):2227–34. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ziv A, Boulet JR, Slap GB. Emergency department utilization by US adolescents. Pediatirics. 1998;101:987–94. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.6.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fine LC, Mollen CJ. A Pilot Study to Assess Candidacy for Emergency Contraception and Interest in Sexual Health Education. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2010;26(6):413–416. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181e0578f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mollen CJ, Miller MK, Hayes KL, Barg FK. Knowledge and Beliefs about Emergency Contraception among Adolescents in the Emergency Department. Accepted for Publication by Ped Emerg Care. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walton MA, Resko S, Whiteside L, Chermack ST, Zimmerman M, Cunningham RM. Sexual Risk Behaviors Among Teens at an Urban Emergency Department: Relationship With Violent Behaviors and Substance Use. J Adol Health. 2011;48:303–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rothman EF, Wise LA, Bernstein E, Bernstein J. Alcohol Use and Sexual Initiation Among Adolescents. J Ethnicity Substance Abuse. 2009;8:129–145. doi: 10.1080/15332640902896984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Healthy People 2020. US Department of HHS; [Accessed June 16, 2011]. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/default.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mollen C, Lavelle J, Hawkins L, Ambrose C, Ruby B. Description of a Novel Pediatric Emergency Department-Based HIV Screening Program for Adolescents. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2008;22(6):505–512. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fein JA, Pailler ME, Barg FK, Wintersteen MB, Hayes K, Tien AY, Diamond GS. Feasibility and Effects of a Web-Based Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment Administered by Clinical Staff in the Pediatric Emergency Department. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(12):1112–1117. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walton MA, Chermack ST, Shope JT, Bingham CR, Zimmerman MA, Blow FC, Cunningham RM. Effects of a brief intervention for reducing violence and alcohol misuse among adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304(5):527–35. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ajzen A. From intentions to actions: a theory of planned behavior. In: Kuhl J, Becman J, editors. Action-control: from cognition to behavior. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1985. pp. 11–139. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walker AE, Grimshaw JM, Armstrong EM. Salient beliefs and intentions to prescribe antibiotics for patients with a sore throat. Br J Health Psychol. 2001;6:347–60. doi: 10.1348/135910701169250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Webber G, Edwards N, Graham ID, Amaratunga C, Gaboury I, Keane V, Ros S, McDowell I. A survey of Cambodian health-care providers HIV knowledge, attitudes and intention to take a sexual history. Intern J STD & AIDS. 2009;20:346–350. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2008.008390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dowd MD, Kennedy C, Knapp JF, Stallbaumer-Rouyer J. Mothers’ and health care providers’ perspectives on screening for intimate partner violence in a pediatric emergency department. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002 Aug;156(8):794–9. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.8.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cornuz J, Ghali WA, Di Carlantonio D, et al. Physicians’ attitudes towards prevention: importance of intervention-specific barriers and physicians’ health habits. Fam Pract. 2000;17(6):535–540. doi: 10.1093/fampra/17.6.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cronholm PF, Barg FK, Pailler ME, Wintersteen MB, Diamond GS, Fein JA. Adolescent Depression: Views of Health Care Providers in a Pediatric Emergency Department. Pediatr Emer Care. 2010;26:111–117. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181ce2f85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langille DB, Mann KV, Gailiunas PN. Primary care physician’s perceptions of adolescent pregnancy and STD prevention practices in a NovaScotia county. Am J Prev Med. 1997;13:324–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Torkko KC, Gershman K, Crane LA, Hamman R, Baron A. Testing for Chlamydia and Sexual History Taking in Adolescent Females: Results From a Statewide Survey of Colorado Primary Care Providers. Pediatrics. 2000;106(3):e32. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.3.e32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sockrider MM, Abramson S, Brooks E, Caviness AC, Pilney S, Koerner C, Macias CG. Delivering Tailored Asthma Family Education in a Pediatric Emergency Department Setting: A Pilot Study. Pediatrics. 2006;117:S135–144. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2000K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Posner JC, Hawkins LA, Garcia-Espana F, Durbin DR. A Randomized, Clinical Trial of a Home Safety Intervention Based in an Emergency Department Setting. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6):1603–08. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goyal M, Zhao H, Mollen CJ. Exploring emergency contraception knowledge, prescription practices, and barriers to prescription for adolescents in the emergency department. Pediatrics. 2009;123:765–70. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PC, Rubin HR. Why Don’t Physicians Follow Clinical Practice Guidelines? A Framework for Improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458–1465. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christakis DA, Rivara FP. Pediatricians’ Awareness of and Attitudes About Four Clinical Practice Guidelines. Pediatrics. 1998;101(5):825–830. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.5.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Curlin FA, Lawrence RE, Chin MH, Lantos JD. Religion, conscience, and controversial clinical practices. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:593–600. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa065316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Upadhya KK, Trent ME, Ellen JM. Impact of Individual Values on Adherence to Emergency Contraception Practice Guidelines Among Pediatric Residents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(10):944–948. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Golden NH, Seigel MW, Fisher M, et al. Emergency contraception: pediatricians’ knowledge, attitudes and opinions. Pediatrics. 2001;107:287–92. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.2.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gadomski AM, Wolff D, Tripp M, Lewis C, Short LM. Changes in Health Care Providers’ Knowledge, Attitudes, Beliefs, and Behaviors Regarding Domestic Violence, Following a Multifaceted Intervention. Acad Med. 2001;76:1045–1052. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200110000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beach MC, Price EG, Gary TL, Robinson KA, Gozu A, Palacio A, Smarth C, Jenckes MW, Feuerstein C, Bass EB, Powe NR, Cooper LA. Cultural Competency: A Systematic Review of Health Care Provider Educational Interventions. Med Care. 2005;43(4):356–373. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156861.58905.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lie DA, Lee-Rav E, Gomez A, Bereknvei S, Braddock CH. Does Cultural Competency Training of Health Professionals Improve Patient Outcomes? A Systematic Review and Proposed Algorithm for Future Research. J Gen Intern Med. 2011 Mar;26(3):317–325. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1529-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giacomini MK, Cook DJ. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXIII. Qualitative research in health care A. Are the results of the study valid? Evidence- Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 2000;284:357–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giacomini MK, Cook DJ. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXIII. Qualitative research in health care B. What are the results and how do they help me care for my patients? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 2000;284:478–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.4.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]