Abstract

Background:

The cerebral network that is active during rest and is deactivated during goal-oriented activity is called the default mode network (DMN). It appears to be involved in self-referential mental activity. Atypical functional connectivity in the DMN has been observed in schizophrenia. One hypothesis suggests that pathologically increased DMN connectivity in schizophrenia is linked with a main symptom of psychosis, namely, misattribution of thoughts.

Methods:

A resting-state pseudocontinuous arterial spin labeling (ASL) study was conducted to measure absolute cerebral blood flow (CBF) in 34 schizophrenia patients and 27 healthy controls. Using independent component analysis (ICA), the DMN was extracted from ASL data. Mean CBF and DMN connectivity were compared between groups using a 2-sample t test.

Results:

Schizophrenia patients showed decreased mean CBF in the frontal and temporal regions (P < .001). ICA demonstrated significantly increased DMN connectivity in the precuneus (x/y/z = −16/−64/38) in patients than in controls (P < .001). CBF was not elevated in the respective regions. DMN connectivity in the precuneus was significantly correlated with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale scores (P < .01).

Conclusions:

In schizophrenia patients, the posterior hub—which is considered the strongest part of the DMN—showed increased DMN connectivity. We hypothesize that this increase hinders the deactivation of the DMN and, thus, the translation of cognitive processes from an internal to an external focus. This might explain symptoms related to defective self-monitoring, such as auditory verbal hallucinations or ego disturbances.

Key words: psychosis, default mode network, arterial spin labeling, functional connectivity, precuneus

Introduction

Cerebral blood flow (CBF) in schizophrenia has been extensively researched for several decades. Mean CBF during the resting state is significantly altered in schizophrenia patients compared with healthy controls (HCs).1,2 The arterial spin labeling (ASL) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) signal is directly linked to CBF and provides a quantitative and absolute measure of regional CBF (rCBF), reflects the level of neuronal activity, and is comparable with positron emission tomography (PET).3,4 Resting-state data of functional MRI (fMRI) and PET can efficiently be parsed into so-called resting-state networks (RSNs).4–6 These RSNs are defined by synchronized spontaneous oscillations between the cortical areas that compose the specific RSN.

The default mode network (DMN) is an RSN that is active during rest and is deactivated during goal-oriented activity.4 The cerebral structures involved in the DMN comprise the posterior cingulate cortex, precuneus, inferior parietal cortex, medial prefrontal cortex, and medial temporal lobe.4,7–10 It is characterized by coherent low-frequency neuronal oscillations that reflect processes such as internal mentation, the generation of self-referential spontaneous thoughts, and task-independent introspection.9

For efficient interaction with the environment, the translation between the self-referential resting-state (default mode) and non–self-referential goal-directed processes is pivotal. The default mode has to be successfully terminated to start any goal-directed process, ie, task-induced deactivation (TiD).11

In schizophrenia, an increase in DMN activity or a failure of DMN deactivation has been postulated to cause misattributions of thoughts because of the functional connection between the DMN and internal mentation.12,13 Therefore, the dynamic competition between the DMN and brain systems that support external attention becomes disturbed.14 Consequently, perceptions arising from imagined scenarios and from the external world become blurred, and the boundary between self and other is dissolved.15 The psychopathological phenomena seen in schizophrenia patients, such as auditory hallucinations, in which self-referential thoughts are attributed to an external agency, or other symptoms with a self-monitoring deficit, such as thought insertion or thought withdrawal, might be explained within this framework.

Deviations within the DMN network have been measured and compared between schizophrenia patients and HCs by using blood oxygen level–dependent (BOLD) fMRI. Most DMN studies have used a region of interest (ROI) seed-based correlation approach, which yields inconsistent results.11,16 Several studies have reported decreased connectivity in parts of the DMN,17–19 whereas others have showed increased connectivity20,21; some others have showed both patterns.22 This inconsistency might be due to methodological differences. However, the most common finding is an increased connectivity within the dorsal hub of the DMN, which consists of the precuneus and dorsal cingulum.16

BOLD-fMRI provides a relative measure of blood perfusion by measuring differences in oxygen consumption. In contrast, ASL provides an absolute quantification of the deviations of CBF and the herefrom computed DMN. In schizophrenia, absolute quantification of the DMN has not been performed; addressing this might help interpret the ambiguous results concerning increased DMN connectivity in this disease.12 As ASL provides quantitative maps of CBF,23 it is not necessary to compare a target region with a reference.24,25 The ASL technique has successfully been used to measure changes in rCBF between healthy individuals and schizophrenia patients,1,26 and for the determination of psychopathological phenomena, such as auditory hallucinations.27,28 Nevertheless, ASL data can be used not only for absolute CBF quantification, but also for the calculation of RSN in general, and in the DMN in particular.29,30

In this study, we used ASL MRI to quantify CBF and subsequently calculate DMNs by using a group-level independent component analysis (ICA) in 34 schizophrenia patients and 27 age-matched HCs. We hypothesized that DMN connectivity in the dorsal hub increases during the resting state in schizophrenia patients, and that this increase correlates positively with psychopathological features. We expected that CBF would be elevated in areas of increased connectivity.

Methods

Patients and Clinical Investigation

Thirty-four patients (P) with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (n = 27) or schizoaffective disorder (n = 7) according to the ICD-10 and 27 HC subjects (HC; matched for age and sex) were included in our study (table 1). Inclusion criteria were age (18–65 y) and right-handedness. Exclusion criteria were MRI contraindications and medical disorders other than schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. None of the patients reported substance misuse in the 4 weeks before or during the study.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics With Mean Values and SDs for Healthy Controls and Schizophrenia Patients

| Controls | Patients | t | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 27 | 34 | ||

| Sex | 15 f/12 m | 16 f/18 m | Fisher’s exact | .61 |

| Age (y) | 39.8±12.6 | 41.5±12.9 | 0.35 | .72 |

| PANSS total score | n.a. | 75.5±17.3 | ||

| PANSS positive subscale | n.a. | 19.9±6.8 | ||

| PANSS negative subscale | n.a. | 18.9±6.1 | ||

| PANSS disorganization subscore34 | n.a. | 12.1±4.1 | ||

| AHRS | n.a. | 34.6±6.2 | ||

| PsyRats | n.a. | 39.7±11.0 | ||

| Cpz (mg) | n.a. | 518.9±235.7 |

Note: f, female; m, male; Cpz, chlorpromazine equivalents; PANSS, Positive and Negative Symptom Scale; PsyRats, Psychotic Symptom Rating Scale; AHRS, Auditory Hallucination Rating Scale; n.a., not applicable.

All patients had medication-resistant positive psychotic symptoms (eg, auditory hallucinations, delusions, and ego disturbances). Therapy refractoriness was defined as having no response to at least 2 antipsychotic treatments in recommended dosages, each administered for at least 8 weeks. Medications remained unchanged since 2 weeks prior to the study. Diagnoses were established on the basis of clinical interviews and review of psychiatric history. The psychopathology assessment, consisting of the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS),31 Psychotic Symptom Rating Scale (PsyRats),32 and Auditory Hallucination Rating Scale (AHRS),33 was performed 20±6 hours (mean ± SD) before MRI acquisition. Participants were told to rest in the MR scanner and to stay awake with their eyes closed. PANSS positive, PANSS negative, and PANSS disorganization34 subscores are reported.

The investigation was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics committee. Participants provided informed written consent to participate in the study.

MRI Data Analysis

MRI was performed using a 3.0-Tesla whole-body MRI system (Magnetom Trio; Siemens Medical Systems) with a standard 12-channel radiofrequency head coil. High-resolution 3D structural MRI and ASL were acquired in 1 session. T1-weighted 3D scans were recorded as magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo (voxel size = 1×1 × 1mm3; inversion time = 1000ms; repetition time [TR] = 2 s; echo time [TE] = 3.4ms) and served as high-resolution 3D anatomical templates for coregistration with functional data.

A pseudocontinuous ASL (pCASL) technique was used to measure CBF.35,36 In this gradient-echo echo-planar imaging sequence, interleaved images with and without labeling were acquired. A delay of 1250 milliseconds was applied between the end of the labeling pulse (label time = 1600ms) and image acquisition (slice-acquisition time = 45ms; field of view = 220mm2; matrix = 64×64; TR/TE = 4000/18ms). A total of 14 slices (voxel size = 3.4×3.4×6mm3; gap = 1.5mm) were acquired in the anterior and posterior commissure line, from inferior to superior, in a sequential order. The pCASL scan comprised 80 acquisitions (40 pairs of label and control images). Total acquisition time was 5 minutes, 44 seconds.

Static Characteristics of CBF/Mean CBF

Data analysis was performed using Matlab (Matlab version 8, release 14; The MathWorks Inc.), statistical parametric mapping (SPM 8; Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, London, England; www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm8/), and an in-house software.37 All ASL time series were first realigned to correct for motion artifacts. See online supplementary material for details on CBF quantification and subject motion.

A global and assumption-free investigation of the whole-brain CBF was computed. Statistics for changes in CBF were computed using the SPM 8 software by comparing CBF values between P and HC in a voxelwise analysis using a 2-sample unpaired t test model. We report clusters >30 (voxel size = 2×2 × 2mm3) with a voxel-level threshold of P < .001 (uncorrected). Regions that survived familywise error (FWE) correction at P < .05 (whole brain) are indicated in table 2.

Table 2.

Brain Regions With Significant Differences in Mean Cerebral Blood Flow Between Healthy Controls and Schizophrenia Patients

| Location | BA | x | y | z | P | t | z | Cluster Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Middle temporal gyrus | 21 | 52 | 8 | −40 | .001a | 5.75 | 5.10 | 475 |

| Medial frontal gyrus | 47 | −54 | 44 | −8 | .001a | 5.64 | 5.02 | 510 |

| Cuneus | 30 | 24 | −74 | 8 | .001 | 4.80 | 4.39 | 31 |

| Inferior occipital gyrus | 17 | −18 | −94 | −16 | .001 | 4.53 | 4.18 | 381 |

| Caudate | n.a. | 26 | −40 | 10 | .001 | 4.4 | 4.07 | 33 |

| Medial frontal gyrus | 11 | 4 | 54 | −12 | .001 | 4.36 | 4.04 | 86 |

| Inferior frontal gyrus | 47 | 56 | 22 | −4 | .001 | 4.32 | 4.01 | 113 |

| Middle frontal gyrus | 9 | −46 | 12 | 30 | .001 | 4.31 | 4.00 | 68 |

| Postcentral gyrus | 1 | −50 | −26 | 60 | .001 | 4.29 | 3.99 | 61 |

| Fusiform gyrus | 19 | −42 | 16 | 34 | .001 | 4.22 | 3.93 | 94 |

| Middle frontal gyrus | 6 | −40 | 10 | 54 | .001 | 4.14 | 3.87 | 77 |

| Fusiform gyrus | 19 | 42 | −74 | −20 | .001 | 4.07 | 3.81 | 87 |

| Medial frontal gyrus | 10 | −10 | 52 | −2 | .001 | 4.05 | 3.79 | 122 |

| Anterior cingulate | 32 | −14 | 42 | 8 | .001 | 3.77 | 3.55 | 40 |

| Middle temporal gyrus | 21 | −66 | −6 | −14 | .001 | 3.72 | 3.51 | 71 |

| Lingual gyrus | 18 | 2 | −86 | −12 | .001 | 3.67 | 3.47 | 46 |

| Inferior frontal gyrus | 10 | 58 | 42 | 0 | .001 | 3.62 | 3.42 | 31 |

| Middle frontal gyrus | 10 | −34 | 56 | 4 | .001 | 3.59 | 3.40 | 43 |

| Middle frontal gyrus | 9 | −6 | 48 | 28 | .001 | 3.47 | 3.30 | 65 |

Note: Contrast healthy controls (HC) > schizophrenia patients (P), 2-sample t test, P < .001, cluster size > 30, statistical parametric mapping (SPM) (t = 59), local maximum peak values according to SPM 8 x, y, z coordinates in Montreal Neurological Institute space; cluster size = number of voxels. BA, Brodmann area.

aFWE (familywise error) corrected at P < .05. The contrast P >HC did not provide any significant results.

Dynamic Characteristics of CBF/DMN Connectivity

DMNs were identified using an ICA that decomposed each individual’s functional ASL data into statistically independent components, each delineating clusters of voxels that exhibited synchronous temporal fluctuations. The DMN was computed using a concatenated group ICA approach38,39 as implemented in the group ICA of the fMRI toolbox (GIFT, http://icatb.sourceforge.net/)38 version 1.3i (a Matlab toolbox). See online supplementary material for details on the ICA.

In regions of interest with existing prior hypotheses (dorsal cingulate, precuneus), results were small-volume corrected within a sphere with a diameter of 15mm around peak coordinates, as reported by Whitfield-Gabrieli et al20 and Anticevic et al,13 and reported at a voxel-level threshold of P < .05, FWE corrected.

Statistics

CBF values were extracted for the whole DMN and for areas with significant differences in the DMN between P and HC. Additionally, normalized CBF values are reported {[voxel CBF – global gray matter (GM) CBF]/SD}. DMN z values of significant ROIs were compared using 2-sided, 2-sample t tests. The association between DMN z values in regions showing a significant increase in P compared with HC, as well as the PANSS, AHRS, and PsyRats scores were assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation. Significance level was set at P < .05 (2 sided).

Results

Group Component for the DMN

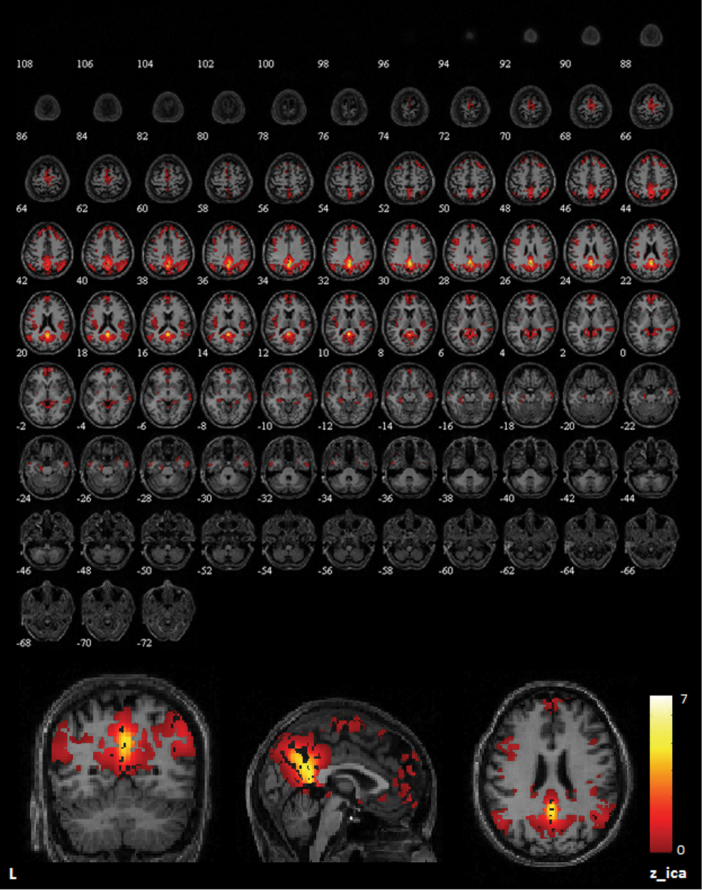

The results of the concatenated group ICA are shown in figure 1. The ICA on a group level identified the DMN. Group-specific DMN maps for HC and P are presented in the online supplementary figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Group component (n = 61) of the default mode network (DMN), sagittal slices, full axial view. DMN distribution from the independent component analysis of the whole data set. The strongest signal is localized in the posterior hub, consisting of the posterior cingulate cortex and the precuneus. The numbers below the upper figures indicate the z coordinate of the axial slice in Montreal Neurological Institute space.

Static Characteristics of CBF/Mean CBF

Compared with HC, P demonstrated significantly de creased CBF in frontal and temporal areas and in the cuneus, inferior occipital gyrus, caudate, anterior cingulate, and lingual, postcentral, and fusiform gyri (table 2). No areas showed an increase in CBF in P compared with HC. CBF extracted for GM did not differ between groups (table 3). CBF reduction observed in the middle temporal gyrus (Brodmann area [BA] 21; x/y/z = 52/8/−40; t = 5.75; z = 5.10; cluster size = 475; df = 59) and in the medial frontal gyrus (BA 47; x/y/z = −54/44/−8; t = 5.64; z = 5.02; cluster size = 510; df = 59), it remained significant after correction for FWEs.

Table 3.

Mean Cerebral Blood Flow (CBF) in the Grey Matter (GM), Default Mode Network (DMN), and Precuneus

| Controls | Patients | t | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GM | 69.7±6.9 | 67.8±7.5 | 1.00 | .32 |

| DMN | 61.3±13.4 | 54.5±15.4 | 1.79 | .08 |

| Precuneus | 55.0±12.8 | 49.6±19.0 | 1.21 | .23 |

| DMN normalized | −1.2±2.0 | −1.8±2.0 | 0.83 | .30 |

| Precuneus normalized | −2.1±1.9 | −2.6±2.7 | 0.77 | .45 |

Note: Mean CBF values (ml/100g/min) with SD are given for the GM, DMN, and precuneus. For the DMN and precuneus, the normalized values are also reported.

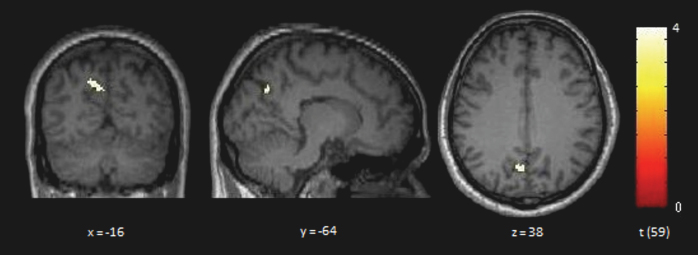

Dynamic Characteristics of CBF/DMN Connectivity

The whole-brain analysis revealed significantly increased DMN connectivity in the precuneus in P compared with HC (BA 7; x/y/z = −16/−64/38; t = 3.76; z = 3.55; cluster size = 51) (figure 2). The ROI analysis in the precuneus indicated significantly increased DMN z values in P compared with HC (P < .001; t = 3.67; df = 59). The results remained significant after correction for FWEs.

Fig. 2.

Brain regions with significant increase in default mode network (DMN) connectivity in patients (P; n = 34) compared with healthy controls (HC; n = 27). Two-sample t test, P < .001, cluster size > 30. Contrast P > HC. Yellow areas show a significantly increased DMN connectivity in P compared with HC in the precuneus, in the dorsal part of the DMN (BA 7, x/y/z = −16/−64/38; cluster size = 51; P < .001; t value = 3.76; z value = 3.55). x, y, z coordinates in Montreal Neurological Institute space.

A significantly increased DMN connectivity (P < .001; t = 3.87; df = 59) in the posterior cerebellar lobe (BA 19; x/y/z = 28/−80/−22; t = 3.83; z = 3.61; cluster size = 61) was detected in HC compared with P. Note that the latter is not a part of the DMN. No other regions reached the level of significance.

CBF in the DMN

CBF in the DMN was higher at a trend level in the HC group (P < .08; t = 1.79; df = 59). There were no significant differences in CBF in the precuneus between P and HC (table 3).

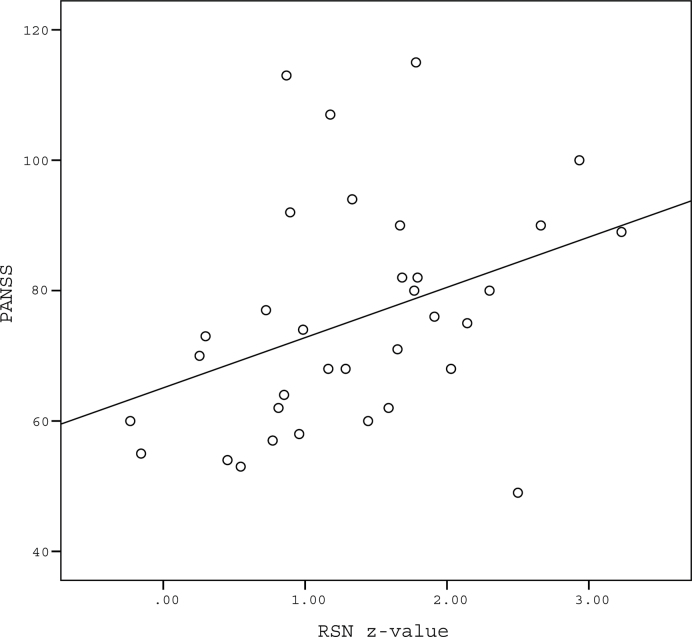

Correlation of DMN Connectivity With Psychopathological Features

In P, the DMN z values in the precuneus and the PANSS total scores were significantly and positively correlated (Spearman’s ρ = .442; P = .009; figure 3). No correlation was found between DMN z values in the precuneus and scores on any of the hallucination-specific scales (PsyRats and AHRS). See further results on correlations (DMN z values and PANSS subscales; DMN z values and CBF) in the online supplemental material.

Fig. 3.

Correlation between general psychopathological features and default mode network (DMN) z values in the precuneus in patients (n = 34). Mean DMN z value in the precuneus and the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS) total score exhibited a significant positive correlation (Spearman’s ρ = .442, P = .009, 2 sided) RSN, resting-state network.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study that investigated both the static and dynamic properties of CBF in schizophrenia. Our main finding suggests the presence of a significant difference in the dynamic characteristics of CBF between schizophrenia patients and HCs, ie, increased DMN connectivity within the posterior hub of the DMN. Functional connectivity in the precuneus correlated with psychopathological features. These findings are in line with DMN connectivity based on conventional BOLD functional connectivity analyses.13,17,20 We expected that the absolute quantification would yield a significantly increased mean CBF in the respective regions, which was not confirmed. Interestingly, CBF in the DMN was reduced at a trend level in P. One possible explanation for this observation is that CBF reductions within the DMN contribute to specific alterations of functional connectivity in patients.

We also replicated previous findings of reduced mean CBF in schizophrenia patients compared with HC, predominantly in the frontal and temporal regions.1,26 Reduced CBF suggests reduced metabolism in the respective regions. Individuals with schizophrenia show impairments in frontal and temporal neurocognitive functions,40 as well as GM volume reduction in these regions.41 We hypothesize that CBF reduction is causally related to the impairments of temporal and frontal brain functions in schizophrenia.

The striking similarity between our results and those of van Lutterveld et al42 has to be mentioned. Those authors investigated healthy individuals with a propensity for auditory hallucinations and reported increased functional connectivity in the dorsal hub of the DMN.

This was also the first study that calculated the DMN based on ASL data in schizophrenia patients. We showed that an ICA on ASL data with GIFT provides reasonable results when extracting DMN data (figure 1). Because of the nature of BOLD and the absence of studies using an absolute quantification of CBF, it is unclear whether the DMN connectivity observed in schizophrenia patients denotes an increase in absolute metabolic activity in the same regions. Although our primary hypothesis of an increased DMN in schizophrenia patients was confirmed, the data did not confirm the second hypothesis of an increase in CBF in the respective regions.

The use of ASL in functional connectivity analyses is a rather new field.43–47 A recently published pCASL DMN study44 demonstrated a large task-related CBF decrease (TiD) in the posterior-inferior precuneus within a healthy population. The posterior cingulate and posterior-inferior precuneus were also the regions that exhibited the highest CBF at rest and during task performance. In the same regions, a decreased TiD in schizophrenia patients during a working memory task has been shown using BOLD-fMRI.20 Hyperconnectivity and decreased TiD correlated negatively with each other, which indicates that a decrease in task-related suppression is associated with an increase in connectivity. Finally, both decreased TiD and increased connectivity were correlated with psychopathological features, ie, with positive and negative symptoms, as measured using the PANSS.11,13,20 These findings converge towards a perturbation within the dorsal parts of the DMN.

The precuneus is involved in several higher-order functions, such as visuospatial imagery, episodic memory retrieval, and self-processing operations.48 It is engaged in first-person perspective taking, the experience of agency, self-related mental representations, and self-consciousness. Some of these functions are severely disturbed in schizophrenia. Moreover, the precuneus has the highest resting metabolic rate of the brain.44,49

The processing of self-referential stimuli in the anterior and posterior midline regions is a fundamental component in the generation of a model of the self and has led to the concept of cortical midline structures.50

A recent study51 suggests that altered connections within or across the DMN and the cerebellum may account for cognitive symptoms that are shared between major depression and schizophrenia. We interpret the lower connectivity in the cerebellum in the patients within this framework and hypothesize a relation to negative and/or cognitive symptoms in schizophrenia.

Some methodological differences between ASL and BOLD regarding DMN analysis have to be mentioned: because of its relatively slow sampling rate (TR = 3–8 s) and the fact that there is no time drift, ASL MR qualifies optimally for the investigation of the slow-frequency oscillations of the DMN (~0.1 Hz). Compared with BOLD-fMRI, the larger fractional ASL signal change is an advantage regarding motion artifacts or subject instability. For stimulations that take longer than 3 minutes, and even shorter durations in less cooperative subjects, the instability in BOLD tends to render ASL a preferable technique.44 Therefore, the pCASL MR technique is useful in studies of schizophrenia patients, in which movement artifacts often decrease the quality of the MR data.

Furthermore, the ICA approach that was used in this study is a model-free approach, which, unlike ROI seed-based analyses, is not bound to a priori predictions.16 ICA z scores represent the likelihood of a given voxel to be part of the network, similar to correlation values. Hence, voxels with high z scores also would have high correlation values amongst each other.52 Accordingly, higher z scores can be interpreted as increased functional connectivity in the respective brain area within the whole network, thus a higher degree or probability of involvement in the network. The group differences indicate that in one group a specific area (cluster of voxels) is more involved (shows stronger functional connectivity) in a given network.38 In terms of our group differences, this indicates that the precuneus exhibits a stronger degree of functional connectivity in the schizophrenia patients than in the healthy subjects group. In summary, perfusion imaging provides additional information that is not available in standard BOLD sequences. Because studies of mean level of perfusion at rest were at the origin of the concept of the default network arising from PET studies,4 perfusion imaging integrates older and newer approaches to achieve the study of the resting state in a single technique.45

The present study explored both a physiological brain measure (rCBF) and a brain functional network (DMN) in a sample of schizophrenia patients. The relationship between brain metabolism and functional connectivity may add important information to the understanding of this disease. Although recent studies53 demonstrated a tight coupling between functional connectivity in the dorsal hub of the DMN and CBF in healthy individuals, our data did not support the assumption that brain metabolism and the resting state are related in the schizophrenia sample. This difference might have been caused by differences in methodology, as the DMN was previously computed based on BOLD data,53 whereas our DMN calculation was derived from ASL data. However, here, schizophrenia patients, and not healthy individuals, were the focus of interest.

A limiting factor of this study was that patients received medication at the time of MR. As mentioned in “Methods” section, medication remained unchanged for at least 2 weeks prior to the study, and all patients showed positive symptoms at the time of MR measurement. An increase in rCBF in the striatum and caudate after the administration of antipsychotic medication has been reported,54 whereas—to the best of our knowledge—changes in rCBF in the precuneus in response to antipsychotic treatment have not been shown before. Nevertheless, we cannot entirely rule out the possibility that medication influenced the findings of this study. However, to obtain maximum homogeneity of the sample, only patients with stable medication status and psychopathology were included.

Some authors proposed the following hypothesis11,16: for efficient deactivation of the DMN and, thus, the translation of cognitive processes from an internal to an external focus, the activity of the DMN must fall below a certain threshold or, inversely, the TiD must go beyond this threshold. This deactivation of the DMN is reflected in a decrease of the activity of the posterior hub of the DMN.44 Consequently, 2 possible sources of failure of deactivation of the DMN are likely: reduced potential for the decrease of DMN activity relative to resting activity (comparable to a blood vessel disease causing decreased responsiveness)16 or absolute increase in DMN activity during rest, reflected in increased CBF, without affecting the potential to decrease DMN activity. In both cases, the deactivation threshold is not reached. Because our data showed no elevation of CBF during rest, this study supports the first hypothesis.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at http://schizophre niabulletin.oxfordjournals.org.

Funding

Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF: 32003B-112578 and 33CM30-124114) to T.D.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- 1. Scheef L, Manka C, Daamen M., et al. Resting-state perfusion in nonmedicated schizophrenic patients: a continuous arterial spin-labeling 3.0-T MR study. Radiology. 2010;256:253–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ingvar DH, Franzén G. Distribution of cerebral activity in chronic schizophrenia. Lancet. 1974;2:1484–1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Xu G, Rowley HA, Wu G., et al. Reliability and precision of pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling perfusion MRI on 3.0 T and comparison with 15O-water PET in elderly subjects at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. NMR Biomed. 2010;23:286–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Raichle ME, MacLeod AM, Snyder AZ, Powers WJ, Gusnard DA, Shulman GL. A default mode of brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Biswal B, Yetkin FZ, Haughton VM, Hyde JS. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRI. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34:537–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lowe MJ, Mock BJ, Sorenson JA. Functional connectivity in single and multislice echoplanar imaging using resting-state fluctuations. Neuroimage. 1998;7:119–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Greicius MD, Krasnow B, Reiss AL, Menon V. Functional connectivity in the resting brain: a network analysis of the default mode hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:253–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Greicius MD, Menon V. Default-mode activity during a passive sensory task: uncoupled from deactivation but impacting activation. J Cogn Neurosci. 2004;16:1484–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jann K, Dierks T, Boesch C, Kottlow M, Strik W, Koenig T. BOLD correlates of EEG alpha phase-locking and the fMRI default mode network. Neuroimage. 2009;45:903–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jann K, Kottlow M, Dierks T, Boesch C, Koenig T. Topographic electrophysiological signatures of FMRI Resting State Networks. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Northoff G, Qin P. How can the brain’s resting state activity generate hallucinations? A ‘resting state hypothesis’ of auditory verbal hallucinations. Schizophr Res. 2011;127:202–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Buckner RL, Andrews-Hanna JR, Schacter DL. The brain’s default network: anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1124:1–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Anticevic A, Gancsos M, Murray JD., et al. NMDA receptor function in large-scale anticorrelated neural systems with implications for cognition and schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:16720–16725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jafri MJ, Pearlson GD, Stevens M, Calhoun VD. A method for functional network connectivity among spatially independent resting-state components in schizophrenia. Neuroimage. 2008;39:1666–1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Frith C. The role of the prefrontal cortex in self-consciousness: the case of auditory hallucinations. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1996;351:1505–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Ford JM. Default mode network activity and connectivity in psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2012;8:49–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Garrity AG, Pearlson GD, McKiernan K, Lloyd D, Kiehl KA, Calhoun VD. Aberrant “default mode” functional connectivity in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:450–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vercammen A, Knegtering H, den Boer JA, Liemburg EJ, Aleman A. Auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia are associated with reduced functional connectivity of the temporo-parietal area. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:912–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bluhm RL, Miller J, Lanius RA., et al. Spontaneous low-frequency fluctuations in the BOLD signal in schizophrenic patients: anomalies in the default network. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:1004–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Thermenos HW, Milanovic S., et al. Hyperactivity and hyperconnectivity of the default network in schizophrenia and in first-degree relatives of persons with schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1279–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rotarska-Jagiela A, van de Ven V, Oertel-Knöchel V, Uhlhaas PJ, Vogeley K, Linden DE. Resting-state functional network correlates of psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2010;117:21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Skudlarski P, Jagannathan K, Anderson K., et al. Brain connectivity is not only lower but different in schizophrenia: a combined anatomical and functional approach. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:61–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Detre JA, Leigh JS, Williams DS, Koretsky AP. Perfusion imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1992;23:37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Buxton RB, Frank LR, Wong EC, Siewert B, Warach S, Edelman RR. A general kinetic model for quantitative perfusion imaging with arterial spin labeling. Magn Reson Med. 1998;40:383–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wong EC, Buxton RB, Frank LR. A theoretical and experimental comparison of continuous and pulsed arterial spin labeling techniques for quantitative perfusion imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1998;40:348–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Walther S, Federspiel A, Horn H., et al. Resting state cerebral blood flow and objective motor activity reveal basal ganglia dysfunction in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2011;192:117–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Homan P, Kindler J, Hauf M, Hubl D, Dierks T. Cerebral blood flow identifies responders to transcranial magnetic stimulation in auditory verbal hallucinations. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2:e189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kindler J, Homan P, Jann K., et al. Reduced neuronal activity in language-related regions after transcranial magnetic stimulation therapy for auditory verbal hallucinations. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73:518–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Orosz A, Jann K, Federspiel A., et al. Reduced cerebral blood flow within the default-mode network and within total gray matter in major depression. Brain Connect. 2012;2:303–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jann K, Orosz A, Dierks T, Wang DJ, Wiest R, Federspiel A. Quantification of network perfusion in ASL cerebral blood flow data with seed based and ICA approaches. Brain Topogr. 2013;26:569–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kay SR, Opler LA, Lindenmayer JP. Reliability and validity of the positive and negative syndrome scale for schizophrenics. Psychiatry Res. 1988;23:99–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Haddock G, McCarron J, Tarrier N, Faragher EB. Scales to measure dimensions of hallucinations and delusions: the Psychotic Symptom Rating Scales (PSYRATS). Psychol Med. 1999;29:879–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hoffman RE, Hawkins KA, Gueorguieva R., et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation of left temporoparietal cortex and medication-resistant auditory hallucinations. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. van der Gaag M, Hoffman T, Remijsen M., et al. The five-factor model of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale II: a ten-fold cross-validation of a revised model. Schizophr Res. 2006;85:280–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dai W, Garcia D, de Bazelaire C, Alsop DC. Continuous flow-driven inversion for arterial spin labeling using pulsed radio frequency and gradient fields. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60:1488–1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wu WC, Fernández-Seara M, Detre JA, Wehrli FW, Wang J. A theoretical and experimental investigation of the tagging efficiency of pseudocontinuous arterial spin labeling. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58:1020–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Federspiel A, Müller TJ, Horn H, Kiefer C, Strik WK. Comparison of spatial and temporal pattern for fMRI obtained with BOLD and arterial spin labeling. J Neural Transm. 2006;113:1403–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Calhoun VD, Adali T, Pearlson GD, Pekar JJ. A method for making group inferences from functional MRI data using independent component analysis. Hum Brain Mapp. 2001;14:140–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Calhoun VD, Adali T, Pekar JJ. A method for comparing group fMRI data using independent component analysis: application to visual, motor and visuomotor tasks. Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;22:1181–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Simon AE, Cattapan-Ludewig K, Zmilacher S., et al. Cognitive functioning in the schizophrenia prodrome. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:761–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Borgwardt S, McGuire P, Fusar-Poli P. Gray matters!–mapping the transition to psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2011;133:63–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lutterveld RV, Diederen KM, Otte WM, Sommer IE. Network analysis of auditory hallucinations in nonpsychotic individuals [published online ahead of print]. Hum Brain Mapp. 2013. 10.1002/hbm.22264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zou Q, Wu CW, Stein EA, Zang Y, Yang Y. Static and dynamic characteristics of cerebral blood flow during the resting state. Neuroimage. 2009;48:515–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pfefferbaum A, Chanraud S, Pitel AL., et al. Cerebral blood flow in posterior cortical nodes of the default mode network decreases with task engagement but remains higher than in most brain regions. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21:233–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Viviani R, Messina I, Walter M. Resting state functional connectivity in perfusion imaging: correlation maps with BOLD connectivity and resting state perfusion. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Várkuti B, Cavusoglu M, Kullik A., et al. Quantifying the link between anatomical connectivity, gray matter volume and regional cerebral blood flow: an integrative MRI study. PLoS One. 2011;6:e14801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Li W, Antuono PG, Xie C., et al. Changes in regional cerebral blood flow and functional connectivity in the cholinergic pathway associated with cognitive performance in subjects with mild Alzheimer’s disease after 12-week donepezil treatment. Neuroimage. 2012;60:1083–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cavanna AE. The precuneus and consciousness. CNS Spectr. 2007;12:545–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cavanna AE, Trimble MR. The precuneus: a review of its functional anatomy and behavioural correlates. Brain. 2006;129:564–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Northoff G, Bermpohl F. Cortical midline structures and the self. Trends Cogn Sci. 2004;8:102–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chen YL, Tu PC, Lee YC, Chen YS, Li CT, Su TP. Resting-state fMRI mapping of cerebellar functional dysconnections involving multiple large-scale networks in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2013;149:26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. McKeown MJ, Makeig S, Brown GG., et al. Analysis of fMRI data by blind separation into independent spatial components. Hum Brain Mapp. 1998;6:160–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Liang X, Zou Q, He Y, Yang Y. Coupling of functional connectivity and regional cerebral blood flow reveals a physiological basis for network hubs of the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:1929–1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Handley R, Zelaya FO, Reinders AA., et al. Acute effects of single-dose aripiprazole and haloperidol on resting cerebral blood flow (rCBF) in the human brain. Hum Brain Mapp. 2013;34:272–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.