Abstract

This study examined hippocampal volume as a putative biomarker for psychotic illness in the Bipolar-Schizophrenia Network on Intermediate Phenotypes (B-SNIP) psychosis sample, contrasting manual tracing and semiautomated (FreeSurfer) region-of-interest outcomes. The study sample (n = 596) included probands with schizophrenia (SZ, n = 71), schizoaffective disorder (SAD, n = 70), and psychotic bipolar I disorder (BDP, n = 86); their first-degree relatives (SZ-Rel, n = 74; SAD-Rel, n = 62; BDP-Rel, n = 88); and healthy controls (HC, n = 145). Hippocampal volumes were derived from 3Tesla T1-weighted MPRAGE images using manual tracing/3DSlicer3.6.3 and semiautomated parcellation/FreeSurfer5.1,64bit. Volumetric outcomes from both methodologies were contrasted in HC and probands and relatives across the 3 diagnoses, using mixed-effect regression models (SAS9.3 Proc MIXED); Pearson correlations between manual tracing and FreeSurfer outcomes were computed. SZ (P = .0007–.02) and SAD (P = .003–.14) had lower hippocampal volumes compared with HC, whereas BDP showed normal volumes bilaterally (P = .18–.55). All relative groups had hippocampal volumes not different from controls (P = .12–.97) and higher than those observed in probands (P = .003–.09), except for FreeSurfer measures in bipolar probands vs relatives (P = .64–.99). Outcomes from manual tracing and FreeSurfer showed direct, moderate to strong, correlations (r = .51–.73, P < .05). These findings from a large psychosis sample support decreased hippocampal volume as a putative biomarker for schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, but not for psychotic bipolar I disorder, and may reflect a cumulative effect of divergent primary disease processes and/or lifetime medication use. Manual tracing and semiautomated parcellation regional volumetric approaches may provide useful outcomes for defining measurable biomarkers underlying severe mental illness.

Key words: schizophrenia, psychotic bipolar disorder, hippocampus, manual tracing, FreeSurfer

Introduction

Alterations in medial temporal lobe anatomy and function are consistently reported in schizophrenia and include (1) hippocampal volume reduction,1–5 (2) elevated hippocampal regional blood flow,6 (3) reduced task-associated activation as probed by novelty and memory tasks,7–10 (4) associations between hippocampal alterations and severity of psychosis,4,6 and (5) attenuation of hippocampal-dependent relational memory dysfunction by antipsychotic medication.11 Furthermore, structural and functional hippocampal abnormalities are found in other psychotic, mood, and anxiety disorders, as well as neurodegenerative conditions12–15 suggesting that hippocampal vulnerability may be a common biomarker underlying a broad array of psychiatric and neurologic phenotypes. Although molecular mechanisms of these hippocampal alterations remain unknown, several putative determinants have been proposed, including glutamate/NMDA-16,17, GABA-18,19, and cortisol-mediated20 metaplasticity changes resulting in hippocampal subfield-specific disease vulnerability and, possibly, psychosis formation.16,21 Given this broad link between hippocampal alterations and psychosis, we examined whether regional hippocampal volumetric characteristics show common and/or distinctive features across the schizophrenia–psychotic bipolar I disorder diagnoses in a large sample of probands and their first-degree relatives from the Bipolar-Schizophrenia Network on Intermediate Phenotypes (B-SNIP),22 with the aim of understanding the biological determinants of lifetime psychosis.

Hippocampal volumetric characteristics have been previously examined in psychotic disorders, mostly in small samples, using a “gold standard” manual tracing region-of-interest (ROI) approach1,13,23–26 and, more recently, semiautomated methods utilizing edge-detection and tissue intensity differences, such as FreeSurfer.2,27,28 In schizophrenia, reduced hippocampal volumes compared with healthy controls (HC) are well documented,1–5 especially for the left hippocampus,27,29,30 though some studies report no volume differences.13,26 In bipolar disorder, data are inconsistent, ranging from normal,1,24,26,31 to decreased,12,13 to increased32 hippocampal volumes compared with controls, with some reports of asymmetric alterations, eg, smaller volume in the right but not the left hippocampus.12,13 A recent meta-analysis33 reported smaller bilateral hippocampal volumes in probands with schizophrenia (SZ) vs bipolar probands. A few small studies have specifically focused on hippocampal volumes in psychotic vs nonpsychotic bipolar phenotypes: Strasser et al 24 found no differences in hippocampal volumes between SZ and nonpsychotic and psychotic bipolar disorder probands (BDP), whereas McDonald et al 31 reported smaller bilateral hippocampi in SZ than in BDP; both found no differences in BDP vs HC. Furthermore, analyses that included the amygdala-hippocampus complex into a single ROI have shown similar volumes across schizophrenia, psychotic bipolar disorder,15,34 and psychotic depression,15 suggesting that the ROI definition may introduce further variability in the volumetric outcomes. No study has examined hippocampal volume in schizoaffective disorder as a unique group, but manual tracing reports from mixed schizophrenia and schizoaffective proband (SAD) samples have shown smaller volumes of hippocampus25,35 and amygdala-hippocampus complex34 compared with HC.

Hippocampal volume alterations have also been reported in biological relatives of psychosis probands, albeit with substantial variability in findings. Studies in relatives of SZ (SZ-Rel)25,36,37 have reported hippocampal volumes intermediate between those found in SZ and HC, with characteristic hippocampal volume reductions observed in unaffected relatives.36,38–40 Seidman et al 39 reported more substantial left hippocampal volume reductions in individuals with 2 or more first-degree relatives with schizophrenia, suggesting familial cosegregation of this biomarker in psychosis. In contrast, other studies found normal hippocampal volumes in SZ-Rel.2,27,41 A few small reports in first-degree relatives of BDP (BDP-Rel) showed hippocampal volumes similar to those in HC,31,42 but larger than those found in probands.43 To date, no study has examined hippocampal characteristics unique to relatives of SAD (SAD-Rel) although the data from mixed schizoaffective disorder/schizophrenia relatives samples have produced outcomes consistent with those in SZ-Rel alone.25,35 No studies have contrasted hippocampal characteristics in relatives based on psychosis-relevant clinical manifestations, ie, relatives with psychosis spectrum disorders vs unaffected relatives.

Overall, hippocampal volume outcomes from the “gold standard” manual and semiautomated studies, all of limited sample size, support diminished volumes in SZ and SAD, with more variable observations in BDP and in biological relatives of psychosis probands. The hippocampal volume abnormalities associated with psychosis are subtle, averaging 2%–4% decrease in SZ (see meta-analyses);3,5 thus, larger samples are necessary to support reliable characterization of these putative brain structure biomarkers.

This study examined hippocampal volume using manual tracing and semiautomated parcellation, FreeSurfer, contrasting these outcomes across the schizophrenia-bipolar I disorder psychosis dimension in a large sample of probands and their first-degree relatives. We tested whether hippocampal volume measures would show common or divergent characteristics across the 3 psychoses diagnoses—schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and psychotic bipolar I disorder—contrasting (1) probands and HC, (2) relatives and HC, and (3) probands and relatives. We hypothesized that (1) probands will show decreased hippocampal volumes compared with HC, consistent across schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and psychotic bipolar I disorder diagnoses, and (2) relatives will show hippocampal volumes similar across the 3 diagnostic groups and intermediate in magnitude between volumes observed in their respective probands and controls.

Methods

Study Sample

Five hundred ninety-six subjects were included in this analysis, including 227 psychosis probands (71 SZ, 70 SAD, and 86 BDP), 224 first-degree relatives (74 SZ-Rel, 62 SAD-Rel, and 88 BDP-Rel), and 145 HC from 2 B-SNIP sites (University of Chicago, J.A.S.; UT Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, C.A.T.). Detailed characteristics of the B-SNIP clinical population are described elsewhere.22 The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at each site and was consistent with standards for the ethical conduct of human research. All subjects provided written informed consent after the study procedures had been fully explained. Axis I diagnoses in probands and affected relatives were established based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Diagnosis (SCID-I/P),44 and Axis II diagnoses in relatives were established based on the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (SIDP-IV).45 Probands were clinically stable, mostly medicated outpatients. Relatives with lifetime psychiatric diagnoses were asymptomatic/mildly symptomatic at the time of the imaging acquisition. Given potential confounders related to lifetime disease burden and treatments, relatives with lifetime Axis I psychotic disorders (n = 26 with “proband-like” psychosis diagnoses, ie, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and psychotic bipolar disorder, and n = 2 with other Axis I psychoses) were excluded. Relatives with psychosis spectrum disorders (cluster A: schizoid, paranoid, and schizotypal personality disorders) (n = 24), those with nonpsychotic Axis I and/or II diagnoses (eg, mood and anxiety disorders, cluster B, C personality disorders) (n = 72), and those completely unaffected (n = 126) were included, providing basis for an exploratory analysis contrasting hippocampal volumes in affected vs unaffected relatives. Rates of DSM-IV Axis I-II diagnoses in relatives are presented in supplementary table 1.

Demographic, clinical, and cognitive characteristics of the study sample are detailed in table 1. There were no between-group differences in age or handedness. The groups differed in sex due to a higher proportion of males among SZ and SAD compared with other groups. While no differences in ethnicity were observed, the groups differed in race due to a higher proportion of African Americans among SZ and SAD. There were differences in years of education, where SZ had lower education attainment than BDP, BDP-Rel, and HC. The proband groups did not differ in age of illness onset, age at first psychiatric hospitalization, or lifetime number of hospitalizations. SZ and SAD had higher Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)46 total, positive, negative, and general subscales scores compared with BDP. SAD showed the highest scores on Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)47 and Young Mania Research Scale (YMRS).48 All proband and relative groups scored lower than controls on the Global Assessment of Functioning, with the lowest ratings observed in SZ and SAD. The Reading Subtest scores from Wide Range Achievement Test (WRAT), used as an estimate of premorbid intellectual functioning, differed across groups, accounted for by lower scores in SZ compared with that in BDP, all relative groups, and HC, as well as lower scores in SZ-Rel compared with BDP and BDP-Rel. Additionally, probands had lower composite and subscale scores on the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS) neuropsychological test battery,49 compared to relatives and controls, consistent with our previous report.50 Most probands were actively treated with various psychotropic medications including antipsychotics (81.9%), mood stabilizers (48.0%), and antidepressants (45.8%); 73.6% of probands were treated with psychotropic agents of more than 1 class. Among relatives, the majority was unmedicated (82.4% SZ-Rel, 69.4% SAD-Rel, and 64.8% BDP-Rel); antidepressants were the most common treatment in all relative groups.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic, Clinical, and Cognitive Characteristics of the Study Sample

| SZ (n = 71) | SAD (n = 70) | BDP (n = 86) | SZ-Rel (n = 74) | SAD-Rel (n = 62) | BDP-Rel (n = 88) | HC (n = 145) | Test Statistic | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||||||||

| Age, years; Mean (SD) | 35.9 (12.4) | 37.6 (12.7) | 35.8 (13.2) | 40.7 (16.1) | 39.3 (15.4) | 38.9 (16.2) | 38.4 (12.4) | F(6,589) = 1.24 | .29 |

| Sex/Male; n (%) | 44 (62.0) | 32 (45.7) | 25 (29.1) | 18 (24.3) | 18 (29.0) | 28 (31.8) | 67 (46.2) | χ2(6) = 34.49 | <.001a |

| Handedness; n (%)b | χ2(12) = 20.11 | .07 | |||||||

| Right handed | 59 (83.1) | 64 (91.4) | 72 (83.7) | 66 (89.2) | 59 (95.2) | 74 (84.1) | 129 (89.0) | ||

| Left handed | 9 (12.7) | 3 (4.3) | 14 (16.3) | 6 (8.1) | 2 (3.2) | 14 (15.9) | 13 (9.0) | ||

| Ambidextrous | 1 (1.4) | 3 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | ||

| Ethnicity/Hispanic; n (%) | 10 (14.2) | 6 (8.6) | 6 (7.0) | 11 (14.9) | 3 (4.8) | 8 (9.1) | 22 (15.2) | χ2(6) = 8.22 | .22 |

| Race; n (%) | χ2(12) = 51.24 | <.001c | |||||||

| Caucasian | 32 (45.1) | 32 (45.7) | 61 (70.9) | 39 (52.7) | 41 (66.1) | 75 (85.2) | 96 (66.2) | ||

| African American | 34 (47.9) | 35 (50.0) | 19 (22.1) | 28 (37.8) | 19 (30.6) | 11 (12.5) | 36 (24.8) | ||

| Other | 5 (7.0) | 3 (4.3) | 6 (7.0) | 7 (9.5) | 2 (3.2) | 2 (2.3) | 13 (9.0) | ||

| Education, years; Mean (SD) | 12.8 (2.5) | 13.3 (2.5) | 14.2 (2.5) | 14.0 (2.3) | 13.8 (2.9) | 14.6 (2.8) | 14.5 (2.3) | F(6,581) = 5.59 | <.001d |

| Clinical characteristics; Mean (SD) | |||||||||

| Age of illness onset, years | 20.4 (8.3) | 19.0 (9.4) | 19.8 (9.2) | — | — | — | — | F(2,222) = 0.46 | .63 |

| Age of first hospitalization, years | 22.6 (7.5) | 24.2 (9.4) | 24.7 (10.1) | — | — | — | — | F(2,190) = 0.92 | .4 |

| Number of lifetime hospitalizations | 5.6 (6.5) | 6.6 (7.0) | 4.6 (6.0) | — | — | — | — | F(2,185) = 1.34 | .26 |

| PANSS | |||||||||

| Total | 75.9 (15.7) | 74.6 (14.0) | 58.8 (13.6) | — | — | — | — | F(2,220) = 34.33 | <.001e |

| Positive subscale | 19.4 (4.9) | 20.3 (4.1) | 13.8 (4.2) | — | — | — | — | F(2,220) = 50.66 | <.001 |

| Negative subscale | 19.2 (6.3) | 16.1 (4.6) | 13.4 (4.3) | — | — | — | — | F(2,220) = 24.39 | <.001 |

| General symptoms subscale | 37.3 (7.8) | 38.2 (7.8) | 31.6 (7.9) | — | — | — | — | F(2,220) = 16.24 | <.001 |

| YMRS | 7.2 (5.8) | 8.4 (5.5) | 5.8 (6.2) | — | — | — | — | F(2,220) = 4.81 | .009f |

| MADRS | 10.1 (8.1) | 14.5 (9.6) | 10.9 (9.3) | — | — | — | — | F(2,220) = 3.79 | .02g |

| GAF | 43.1 (9.7) | 44.5 (9.7) | 58.9 (12.0) | 76.0 (12.3) | 76.1 (12.9) | 75.2 (12.1) | 86.2 (5.0) | F(6, 586) = 234.32 | <.001h |

| Cognitive characteristics | |||||||||

| WRAT IQ, Mean (SD) | 92.5 (16.5) | 96.2 (13.7) | 102.2 (14.2) | 94.9 (15.0) | 101.3 (17.0) | 102.5 (13.3) | 100.9 (14.2) | F(6,580) = 5.76 | <.001i |

| BACS, z-score, Mean (SD) | |||||||||

| Composite | −1.7 (1.2) | −1.4 (.2) | −0.9 (1.3) | −0.5 (1.1) | −0.3 (1.3) | −0.08 (1.2) | −0.09 (1.2) | F(6,570) = 21.8 | <.001j |

| Verbal memory | −1.1 (1.3) | −0.8 (1.3) | −0.5 (1.3) | −0.4 (1.3) | −0.2 (1.1) | −0.2 (1.2) | −0.1 (1.1) | F(2,533) = 5.82 | <.001 |

| Digit sequencing | −1.2 (1.2) | −0.9 (1.2) | −0.7 (1.2) | −0.4 (1.1) | −0.2 (1.1) | −0.04 (1.1) | −0.2 (1.2) | F(2,533) = 9.9 | <.001 |

| Token motor | −1.3 (1.2) | −1.5 (1.0) | −0.9 (1.3) | −0.4 (1.0) | −0.2 (0.9) | −0.2 (1.0) | −0.02 (1.1) | F(2,527) = 20.9 | <.001 |

| Verbal fluency | −0.8 (1.2) | −0.3 (1.1) | −0.2 (1.1) | −0.1 (1.1) | 0.2 (1.3) | 0.2 (1.2) | 0.1 (1.1) | F(2, 33) = 6.34 | <.001 |

| Symbol coding | −1.3 (1.1) | −1.2 (1.2) | −0.9 (1.0) | −0.5 (1.1) | −0.2 (1.0) | −0.2 (1.0) | 0.02 (1.0) | F(2,533) = 19.6 | <.001 |

| Tower of London | −0.8 (1.4) | −0.6 (1.3) | −0.2 (1.2) | −0.2 (1.0) | −0.2 (1.2) | 0.2 (0.8) | −0.002 (1.1) | F(2,532) = 6.6 | <.001 |

| Concomitant medications; n (%)b | |||||||||

| Off-psychotropic medications | 7 (9.9) | 6 (8.6) | 5 (5.9) | 61 (82.4) | 43 (69.4) | 57 (64.8) | 140 (96.6) | — | — |

| Antipsychotics (any) | 62 (87.3) | 59 (84.3) | 65 (75.6) | 1 (1.4) | 2 (3.2) | 5 (5.7) | 0 (0.0) | — | — |

| Typical | 9 (12.7) | 5 (7.1) | 8 (9.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | — | — |

| Atypical | 53 (74.7) | 54 (77.1) | 57 (66.3) | 1 (1.4) | 2 (3.2) | 5 (5.7) | 0 (0.0) | — | — |

| Mood stabilizers (any) | 14 (19.7) | 38 (54.3) | 57 (66.3) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (9.7) | 8 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | — | — |

| Lithium | 3 (4.2) | 7 (10.0) | 20 (23.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.2) | 2 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | — | — |

| Other | 11 (15.5) | 31 (44.3) | 37 (43.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (6.5) | 6 (6.8) | 0 (0.0) | — | — |

| Antidepressants (any) | 26 (36.6) | 36 (51.4) | 42 (48.8) | 10 (13.5) | 15 (24.2) | 19 (21.6) | 1 (0.7) | — | — |

| Tricyclic | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.3) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | — | — |

| Other (SSRI, SNRI, etc.) | 25 (35.2) | 36 (51.4) | 40 (46.5) | 9 (12.2) | 14 (22.6) | 19 (21.6) | 1 (0.7) | — | — |

| Antiparkinsonian | 11 (15.5) | 7 (10.0) | 8 (9.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | — | — |

| Stimulants | 6 (8.5) | 4 (5.7) | 7 (8.1) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.8) | 6 (6.8) | 0 (0.0) | — | — |

| Combined medications | 43 (60.6) | 57 (81.4) | 67 (77.9) | 3 (4.1) | 7 (11.3) | 10 (11.4) | 0 (0.0) | — | — |

Note: SZ, probands with schizophrenia; SAD, probands with schizoaffective disorder; BDP, probands with psychotic bipolar I disorder; SZ-Rel, relatives of probands with schizophrenia; SAD-Rel, relatives of probands with schizoaffective disorder; BDP-Rel, relatives of probands with psychotic bipolar I disorder; HC, healthy controls; PANSS, the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; YMRS, the Young Mania Rating Scale; MADRS, the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale; GAF, the Global Assessment of Functioning; WRAT, Wide Range Achievement Test IQ estimate; BACS, the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia.

aSex: Higher proportion of males in (1) SZ vs BDP (χ2(1) = 15.78, P < .001), all relative groups (SZ-Rel [χ2(1) = 19.47, P < .001], SAD-Rel [χ2(1) = 13.14, P < .001], BDP-Rel [χ2(1) = 13.23, P < .001]), and HC (χ2(1) = 4.13, P = .04); (2) SAD vs BDP (χ2(1) = 3.92, P < .047) and SZ-Rel (χ2(1) = 6.35, P = .01); and (3) HC vs BDP (χ2(1) = 6.35, P = .01) and all relative groups (SZ-Rel [χ2(1) = 8.98, P = .003], SAD-Rel [χ2(1) = 4.95, P = .03], BDP-Rel [χ2(1) = 4.48, P = .03]).

bMissing data: (1) Handedness: 2/71 SZ, 2/74 SZ-Rel, 1/62 SAD-Rel, 2/145 HC; (2) Concomitant medications: 2/71 SZ, 2/74 SZ-Rel, 1/62 SAD-Rel, 1/88 BDP-Rel, 1/145 HC. Each psychotropic medication class in each subject is reported separately. The number of subjects who were treated with more than 1 psychotropic medication is indicated under “Combined medications.”

cRace: Higher proportion of African Americans in (1) SZ vs BDP (χ2(1) = 10.89, P = .001), HC (χ2(1) = 10.28, P = .001), and relatives (SAD-Rel [χ2(1) = 4.3, P = .04], BDP-Rel [χ2(1) = 25.04, P < .001]; and (2) SAD vs BDP [χ2(1) = 11.54, P < .001], HC [χ2(1) = 11.01, P < .001], and relatives (SAD-Rel [χ2(1) = 4.67, P = .03], BDP-Rel [χ2(1) = 26.03, P < .001]). Lower proportion of African Americans in BDP vs SZ-Rel [χ2(1) = 4.66, P = .03].

dEducation: Lower years of education in (1) SZ vs BDP (P = .009), BDP-Rel (P < .001), and HC (P < .001); (2) SAD vs BDP-Rel (P = .02) and HC (P = .02).

ePANSS/total: Lower scores in BDP vs SZ (P < .001) and SAD (P < .001). PANSS/positive: Lower scores in BDP vs SZ (P < .001) and SAD (P < .001). PANSS/negative: Lower scores in BDP vs SZ (P < .001) and SAD (P = .002). PANSS/general: Lower scores in BDP vs SZ (P < .001) and SAD (P < .001).

fYMRS: Higher scores in SAD vs BDP (P = .02).

gMADRS: Higher scores in SAD vs BDP (P = .03).

hGAF: Lower scores in (1) all proband and relative groups vs HC (all P < .001); (2) SZ and SAD vs BDP, all relative groups, and HC (all P < .001).

iWRAT: (1) Lower scores in SZ vs BDP (P < .001), SAD-Rel (P < .01), BDP-Rel (P < .001), and HC (P < .002); (2) SZ-Rel vs BDP (P = .03) and BDP-Rel (P = .02).

jBACS composite: (1) Lower scores in SZ vs BDP (P = .002), all relative groups (P < .001), and HC (P < .001); (2) SAD vs BDP, all relatives and HC (all P < .001); (3) BDP vs SAD-Rel (P = .045), BDP-Rel and HC (all P < .001). Verbal memory: (1) Lower scores in SZ vs SZ-Rel (P = .02), SAD-Rel (P = .006), BDP-Rel and HC (all P < .001); (2) SAD vs HC (P = .01). Digit sequencing: (1) Lower scores in SZ vs BDP (P = .048), all relatives and HC (all P < .001); (2) SAD vs SAD-Rel (P = .03), BDP-Rel and HC (all P < .001); BDP vs BDP-Rel (P = .006). Token motor: (1) Lower scores in SZ vs all relatives and HC (all P < .001); (2) SAD vs BDP (P = .01), all relatives and HC (all P < .001). Verbal fluency: (1) Lower scores in SZ vs BDP (P = .04); SZ-Rel (P = .02); SAD-Rel, BDP-Rel, and HC (all P < .001). Symbol coding: (1) Lower scores in SZ and SAD vs all relatives and HC (all P < .001, except for SAD vs SZ-Rel, P = .006); (2) BDP vs SAD-Rel (P = .009), BDP-Rel and HC (P < .001). Tower of London: (1) Lower scores in SZ and SAD vs BDP-Rel and HC (all P < .001, except for SAD vs HC, P = .02).

Structural Magnetic Resonance Imaging Acquisition and the Hippocampal ROI Definitions

Whole brain structural magnetic resonance imaging (sMRI) 3D images were acquired on 3Tesla scanners (University of Chicago: GE Signa, UT Southwestern Medical Center: Philips Achieva). All subjects at each site were scanned on the same magnet. High-resolution isotropic T1-weighted Magnetization Prepared RApid Gradient Echo (MPRAGE) sequences were obtained following the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative protocol (http://adni.loni.usc.edu). The MPRAGE sequence parameters were comparable across sites (detailed in supplementary methods).

All images were processed by experienced analysts (manual ROI tracing: S.J.M.A., T.A.G., A.P.R.; FreeSurfer: A.N.F., N.T.) blind to subjects’ clinical characteristics. Manual hippocampal ROI tracing was performed using 3DSlicer/v.3.6.3 (http://www.slicer.org). Within- and between-rater reliability was established at >90% agreement and checked every 4 weeks throughout tracing period. Tracing was performed on the coronal view, with all views simultaneously visible in 3DSlicer.51 The area defined as hippocampal ROI is bounded laterally and medially by the lateral ventricle, anteriorly by the hippocampal-amygdala transitional zone, posteriorly by the crus of the fornix, inferiorly by the subiculum, and superiorly by the alveus, similar to Keshavan et al 23 (detailed in supplementary methods and supplementary figure 1A). Hippocampal mask labeling relied on a tissue-based definition of the hippocampus proper and included cornu ammonis1 (CA1), CA2/3, dentate gyrus/CA4, and fimbria, avoiding subiculum, entorhinal cortex, and hippocampus-amygdala transitional zone. All ROI definitions were checked against a standardized anatomical brain atlas.52

Hippocampal volume outputs were extracted from FreeSurfer/v.5.1-64bit (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu), following standardized steps of preprocessing, subcortical and cortical parcellation, and automated labeling algorythm53–55 (detailed in supplementary methods). The hippocampal mask included CA1, CA2/3, CA4/dentate gyrus, subiculum/presubiculum, and fimbria (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu), yielding a more inclusive ROI than our manual tracing definition (supplementary figure 1B). Left and right hippocampal volumes (as primary outcomes) as well as total intracranial volume (as a covariate in mixed model analyses) from FreeSurfer were used. Intracranial volumes (group mean ± standard deviation, mm3: SZ, 1488796.49 ± 217813.15; SAD, 1389376.66 ± 186550.83; BDP, 1444642.19 ± 175834.12; SZ-Rel, 1425362.36 ± 197966.93; SAD-Rel, 1417176.02 ± 158748.94; BDP-Rel, 1495038.38 ± 158848.76; HC, 1451021.05 ± 177621.46) were comparable to previously reported in similar clinical populations.28,56 There was an effect of diagnostic group on intracranial volume (F(6,505) = 2.78, P = .01), accounted for by lower volume in SZ vs BDP-Rel (adjusted P = .02); the rest of pairwise group comparisons were nonsignificant.

Statistical Analyses

A one-way analysis of variance with a subsequent post hoc Tukey Honest Significant Difference test and Yates corrected chi-square test were used, as appropriate, for demographic, clinical, and cognitive variables. To test a priori hypotheses, the left and right hippocampal volumes from manual tracing and semiautomated parcellation/FreSurfer were contrasted in (1) probands (SZ, SAD, and BDP) and controls, (2) relatives (SZ-Rel, SAD-Rel, and BDP-Rel) and controls, and (3) probands and their respective relatives (SZ vs SZ-Rel, SAD vs SAD-Rel, and BDP vs BDP-Rel). A maximum likelihood approach was used to fit mixed-effect regression models for the left and right hippocampal volume from manual or semiautomated tracing variables (SAS9.3 Proc MIXED procedure) controlling for the following covariates: age, sex, handedness (left-handed indicator), and FreeSurfer-derived total intracranial volume. The family cluster (ie, a random code assigned to all probands and relatives from the same pedigree) and site variables were incorporated as random effects in the model. The model specified the covariance structure within subjects using an unstructured model to account for the within-subject correlation across family clusters and sites. A family cluster effect was included in the mixed-effect model only for analyses comparing probands and their respective relatives. F test was used to test a diagnostic group variance in mean estimates, and t test was used to test pairwise between-group differences in mean estimates of the left and right hippocampal volumes from manual tracing and FreeSurfer.

Fourteen percent of the study sample (including 9 SZ, 6 SAD, 7 BDP, 17 SZ-Rel, 7 SAD-Rel, 21 BDP-Rel, and 17 HC) had missing FreeSurfer-derived hippocampal volume and total intracranial volume data. The missing intracranial volume variables were imputed using multiple imputation (MI) method57 and subsequently used as a covariate in both manual- and FreeSurfer-based hippocampal volume analyses. MI is a simulation-based inferential tool operating on multiple completed data sets, where the missing values are replaced by random draws from their respective predictive distributions following Monte Carlo Markov Chain (SAS9.3 Proc MI procedure). This study used 50 sets of completed data, then analyzed by standard complete data methods, and the results were combined into a single inferential statement using rules to yield estimates, standard errors, and P values that formally incorporate the missing-data uncertainty into the modeling process (SAS9.3 Proc MIANALYZE).

In addition, a series of exploratory analyses was conducted to examine potential disease and medication effects on hippocampal volume using maximum likelihood mixed-effect regression models (SAS9.3 Proc MIXED). (1) To explore whether hippocampal volume outcomes cosegregate in probands and relatives within the same pedigree, relatives were stratified by the hippocampal volumes in their respective probands using a “median split” approach.8 Subsequently, relatives of probands with hippocampal volumes above vs below group median were compared. (2) To examine effect of lifetime mild psychosis manifestations on hippocampal volume, relatives with psychosis spectrum/cluster A personality disorders (n = 24) were contrasted with relatives without lifetime psychosis (n = 198), including those completely unaffected (n = 126) and those with nonpsychotic Axis I/II disorders (n = 72). (3) Pearson correlations were computed between hippocampal volumes and symptom severity scores from PANSS, YMRS, and MADRS (in probands) and between hippocampal volumes and BACS composite and declarative/verbal memory scores (in proband, relative, and control groups). (4) To investigate effect of active medication use, hippocampal volume outcomes were contrasted in all probands combined who were actively treated with antipsychotic medications vs those off-antipsychotics and those on- vs off-lithium. In addition, Pearson correlations between antipsychotic dose chlorpromazine equivalents58 and hippocampal volumes from manual tracing and FreeSurfer were calculated.

Pearson correlations between hippocampal volume outcomes from the 2 sMRI methodologies were also computed.

Results

Hippocampal Volume in Probands

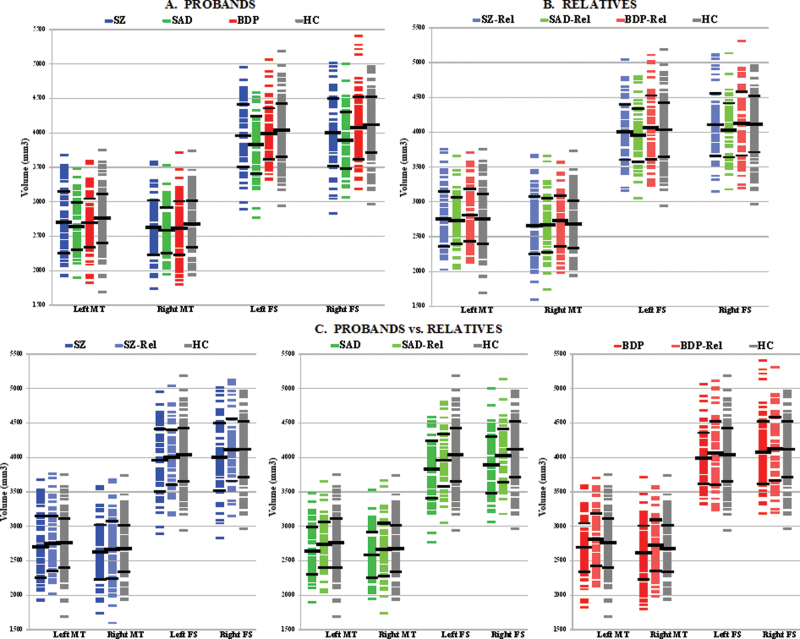

Hippocampal volume outcomes in the psychosis probands and HC from manual tracing and FreeSurfer are presented in table 2A and figure 1A. Effect of the diagnostic group was observed for the left manual (P = .088, trend) and bilateral FreeSurfer (left, P = .005; right, P = .001) measures. A priori planned pairwise comparisons showed lower hippocampal volumes in SZ and SAD compared with HC based on manual tracing (P = .02–.09, except for the right hippocampus in SAD P = .14) and FreeSurfer (P = .0007–.009). In contrast, all outcomes in BDP were not different from controls (P = .18–.55). Furthermore, FreeSurfer measurements showed reduced hippocampal volumes in SZ and SAD compared with BDP (P = .02–.07).

Table 2.

Hippocampal Volume Outcomes in Probands, Relatives, and Healthy Controls Based on Manual Tracing and FreeSurfer

| Hippocampal Volume Measure | Hippocampal Volume, Mean ± SD, mm3 | Diagnostic Group Effect | Planned Pairwise Comparisons | df | t | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Probands | ||||||

| Manuala | ||||||

| Left (n = 368) | SZ, 2691.73±447.45 SAD, 2638.75±344.41 BDP, 2689.55±351.71 HC, 2752.59±357.48 |

F(3,8.7×10 5 ) = 2.18, P = .09 b | SZ vs HC | 353.00 | 2.33 | .02 |

| SAD vs HC | 353.03 | 1.67 | .09 | |||

| BDP vs HC | 354.68 | 1.34 | .18 | |||

| SZ vs SAD | 351.07 | 0.56 | .57 | |||

| SZ vs BDP | 353.28 | 0.93 | .35 | |||

| SAD vs BDP | 354.09 | 0.35 | .72 | |||

| Right (n = 368) | SZ, 2621.78±392.91 SAD, 2579.01±333.83 BDP, 2612.02±391.66 HC, 2671.77±339.26 |

F(3,1.64×105) = 1.52, P = .21b | SZ vs HC | 354.65 | 1.92 | .06 |

| SAD vs HC | 353.86 | 1.50 | .14 | |||

| BDP vs HC | 355.57 | 0.99 | .32 | |||

| SZ vs SAD | 353.25 | 0.36 | .72 | |||

| SZ vs BDP | 354.42 | 0.86 | .39 | |||

| SAD vs BDP | 354.32 | 0.49 | .63 | |||

| FreeSurfera | ||||||

| Left (n = 328) | SZ, 3952.95±453.58 SAD, 3821.80±415.74 BDP, 3979.70±371.57 HC, 4030.24±388.65 |

F(3,319) = 4.39, P = .005 | SZ vs HC | 319 | 2.64 | .009 |

| SAD vs HC | 319 | 3.01 | .003 | |||

| BDP vs HC | 319 | 0.60 | .55 | |||

| SZ vs SAD | 319 | 0.29 | .77 | |||

| SZ vs BDP | 319 | 1.85 | .07 | |||

| SAD vs BDP | 319 | 2.16 | .03 | |||

| Right (n = 332) | SZ, 4000.92±491.60 SAD, 3886.05±412.06 BDP, 4064.61±451.76 HC, 4112.88±405.26 |

F(3,323) = 5.46, P = .001 | SZ vs HC | 323 | 3.41 | .0007 |

| SAD vs HC | 323 | 2.98 | .003 | |||

| BDP vs HC | 323 | 0.86 | .39 | |||

| SZ vs SAD | 323 | 0.39 | .70 | |||

| SZ vs BDP | 323 | 2.33 | .02 | |||

| SAD vs BDP | 323 | 1.92 | .06 | |||

| B. Relatives | ||||||

| Manuala | ||||||

| Left (n = 367) | SZ-Rel, 2746.96±395.51 SAD-Rel, 2727.64±335.09 BDP-Rel, 2802.42±379.17 HC, 2752.59±357.48 |

F(3,1.7×105) = 0.05, P = .99b | SZ-Rel vs HC | 341.89 | 0.36 | .72 |

| SAD-Rel vs HC | 349.82 | 0.11 | .91 | |||

| BDP-Rel vs HC | 339.66 | 0.08 | .93 | |||

| SZ-Rel vs SAD-Rel | 346.28 | 0.21 | .83 | |||

| SZ-Rel vs BDP-Rel | 338.78 | 0.26 | .79 | |||

| SAD-Rel vs BDP-Rel | 342.75 | 0.03 | .97 | |||

| Right (n = 365) | SZ-Rel, 2656.15±414.76 SAD-Rel, 2658.91±385.94 BDP-Rel, 2718.95±367.04 HC, 2671.77±339.26 |

F(3,2.0×105) = 0.23, P = .87b | SZ-Rel vs HC | 340.04 | 0.48 | .63 |

| SAD-Rel vs HC | 346.49 | 0.13 | .89 | |||

| BDP-Rel vs HC | 341.00 | 0.79 | .43 | |||

| SZ-Rel vs SAD-Rel | 343.19 | 0.29 | .77 | |||

| SZ-Rel vs BDP-Rel | 336.05 | 0.28 | .78 | |||

| SAD-Rel vs BDP-Rel | 345.15 | 0.55 | .58 | |||

| FreeSurfera | ||||||

| Left (n = 303) | SZ-Rel, 3998.0±399.33 SAD-Rel, 3951.89±381.76 BDP-Rel, 4060.88±459.32 HC, 4030.24±388.65 |

F(3,294) = 0.39, P = .76 | SZ-Rel vs HC | 294 | .43 | .67 |

| SAD-Rel vs HC | 294 | .68 | .49 | |||

| BDP-Rel vs HC | 294 | .48 | .63 | |||

| SZ-Rel vs SAD-Rel | 294 | .96 | .34 | |||

| SZ-Rel vs BDP-Rel | 294 | .79 | .43 | |||

| SAD-Rel vs BDP-Rel | 294 | .20 | .84 | |||

| Right (n = 306) | SZ-Rel, 4102.44±449.27 SAD-Rel, 4023.24±389.15 BDP-Rel, 4117.12±457.78 HC, 4112.88±405.26 |

F(3,297) = 1.00, P = .39 | SZ-Rel vs HC | 297 | 0.65 | .52 |

| SAD-Rel vs HC | 297 | 0.72 | .47 | |||

| BDP-Rel vs HC | 297 | 1.16 | .25 | |||

| SZ-Rel vs SAD-Rel | 297 | 1.19 | .23 | |||

| SZ-Rel vs BDP-Rel | 297 | 1.57 | .12 | |||

| SAD-Rel vs BDP-Rel | 297 | 0.34 | .74 | |||

| C. Probands vs Relatives | ||||||

| Manual | ||||||

| Left | — | — | SZ vs SZ-Rel | 57.56 | 2.72 | .009 |

| SAD vs SAD-Rel | 47.07 | 1.78 | .08 | |||

| BDP vs BDP-Rel | 63.34 | 2.18 | .03 | |||

| Right | — | — | SZ vs SZ-Rel | 57.76 | 2.95 | .005 |

| SAD vs SAD-Rel | 47.05 | 1.84 | .07 | |||

| BDP vs BDP-Rel | 66.34 | 1.72 | .09 | |||

| FreeSurfer | ||||||

| Left | — | — | SZ vs SZ-Rel | 37 | 3.25 | .003 |

| SAD vs SAD-Rel | 40 | 1.98 | .05 | |||

| BDP vs BDP-Rel | 51 | 0.46 | .64 | |||

| Right | — | — | SZ vs SZ-Rel | 38 | 3.37 | .002 |

| SAD vs SAD-Rel | 40 | 2.43 | .02 | |||

| BDP vs BDP-Rel | 52 | 0.00 | .997 | |||

Note: SZ, probands with schizophrenia; SAD, probands with schizoaffective disorder; BDP, probands with psychotic bipolar I disorder; SZ-Rel, relatives of probands with schizophrenia; SAD-Rel, relatives of probands with schizoaffective disorder; BDP-Rel, relatives of probands with psychotic bipolar I disorder; HC, healthy controls.

aSample sizes are indicated per hippocampal volume measure.

bAdjusted degrees of freedom (df) for pairwise group comparisons for manual hippocampal volumes were calculated similar to Barnard and Rubin 87 due to a large df following original MI method suggested by Rubin.55

Statistically significant and trend level outcomes are indicated in Bold.

Fig. 1.

Hippocampal volume outcomes from manual tracing and FreeSurfer in probands, relatives, and healthy controls. The scatter plots show individual hippocampal volumes derived from manual tracing and FreeSurfer in each proband, relative, or HC subject. The horizontal bars indicate group means and standard deviations. SZP, probands with schizophrenia; SADP, probands with schizoaffective disorder; BDP, probands with psychotic bipolar I disorder; SZR, relatives of probands with schizophrenia; SADR, relatives of probands with schizoaffective disorder; BDR, relatives of probands with psychotic bipolar I disorder; HC, healthy controls; L Hipp, the left hippocampus; R Hipp, the right hippocampus; MT, manual tracing; FS, FreeSurfer.

Hippocampal Volume in Relatives

Hippocampal volume outcomes in relatives of the psychosis probands and HC based on manual tracing and FreeSurfer are reported in table 2B and figure 1B. No overall effect of the diagnostic group (P = .39–.99) was observed for any of the hippocampal measures, using either methodology. Likewise, planned pairwise comparisons showed no between-group differences in any of the relative groups vs controls (P = .25–.93) or across the 3 relative diagnostic groups (P = .12–.97).

Hippocampal Volume Outcomes in Probands vs Relatives

Hippocampal volume outcomes in the psychosis probands contrasted with their relatives are presented in table 2C and figure 1C. SZ and SAD had lower hippocampal volumes than their respective relatives based on manual tracing (P = .005–.08) and semiautomated parcellation (P = .002–.05). BDP showed decreased hippocampal volumes compared with their relatives based on manual tracing (P = .03–.09), but not FreeSurfer (P = .64–.997).

Effect of Illness and Medication on Hippocampal Volume

Relatives’ subgroups stratified by hippocampal volumes in their respective probands based on “median split” showed numerically lower volumes in the relatives of probands whose hippocampal volumes fell below group median compared with relatives of probands with volumes above group median (supplementary table 2). These differences were statistically significant in BDP-Rel for the left manual tracing volume (P = .001) and at a trend level in SZ-Rel (left manual, P = .051; right FreeSurfer, P = .052) and SAD-Rel (left manual, P = .068) relative subgroups.

No between-group differences in hippocampal volume were found in relatives with lifetime psychosis spectrum disorders vs relatives unaffected by psychosis for either manual (P = .64–.73) or semiautomated (P = .58–.71) hippocampal ROIs (supplementary table 3).

PANSS total and positive subscale scores correlated inversely with bilateral hippocampal volumes from manual tracing and FreeSurfer (r = −.14 to −.3, P < .05) (supplementary table 4), whereas no correlations were found with PANSS negative and general subscale scores, YMRS, or MADRS scores in any of the proband groups. BACS composite and verbal memory scores showed direct correlations with manual tracing and FreeSurfer hippocampal volume outcomes across proband, relative, and control groups (supplementary table 4).

No differences in hippocampal volumes were found in probands actively treated with antipsychotic medication(s) vs those off-antipsychotic(s) (P = .65–.94) (table 3A). Probands treated with lithium had numerically higher hippocampal volumes compared with those off-lithium across all measures. However, this difference was statistically significant only for the right hippocampal volume from FreeSurfer (P = .047). All correlations between antipsychotic dose chlorpromazine equivalents and manual and FreeSurfer hippocampal volume outcomes were nonsignificant (table 3B).

Table 3.

Associations Between Psychotropic Medications and Hippocampal Volume Outcomes

| A. Hippocampal Volume Comparisons in Probands On- and Off-Antipsychotic Medications and Lithium | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hippocampal Volume Measure | Proband Groups by Active Medication Usea | Hippocampal Volume, Mean ± SD, mm3 | df | t | P |

| Antipsychotics | |||||

| Manual left | On (n = 184) | 2678.05±372.76 | 220.25 | 0.46 | .65 |

| Off (n = 39) | 2631.19±414.40 | ||||

| Manual right | On (n = 185) | 2613.52±354.90 | 220.27 | 0.46 | .65 |

| Off (n = 39) | 2545.04±448.60 | ||||

| FS left | On (n = 168) | 3935.34±403.89 | 194 | 0.07 | .94 |

| Off (n = 33) | 3833.45±461.79 | ||||

| FS right | On (n = 169) | 4016.38±439.42 | 196 | 0.28 | .78 |

| Off (n = 34) | 3882.74±519.12 | ||||

| Lithium | |||||

| Manual left | On (n = 30) | 2686.48±362.69 | 220.25 | 0.43 | .67 |

| Off (n = 193) | 2667.27±383.24 | ||||

| Manual right | On (n = 30) | 2640.55±359.67 | 220.27 | 0.10 | .92 |

| Off (n = 194) | 2595.58±375.20 | ||||

| FS left | On (n = 25) | 4019.88±351.42 | 194 | 1.13 | .26 |

| Off (n = 176) | 3904.23±421.53 | ||||

| FS right | On (n = 26) | 4171.31±453.90 | 196 | 2.00 | .047 |

| Off (n = 177) | 3967.95±450.69 | ||||

| B. Pearson Correlations Between Antipsychotic Dose Chlorpromazine Equivalents and Hippocampal Volumes | |||||

| Antipsychotic Dose Chlorpromazine Equivalentsb | |||||

| SZ (n = 39) | SAD (n = 25) | BDP (n = 86) | |||

| Mean ± SD, mg | 472.11±365.93 | 619.72±639.13 | 306.75±450.26 | ||

| Pearson Correlations in All Probands Combined | |||||

| Hippocampal Volume Measure | n | r | P | ||

| Manual left | 109 | .02 | .86 | ||

| Manual right | 104 | .08 | .39 | ||

| FS left | 110 | −.07 | .47 | ||

| FS right | 104 | .02 | .82 | ||

Note: Manual right, right hippocampal volume from manual tracing; Manual left, left hippocampal volume from manual tracing; FS right, right hippocampal volume from FreeSurfer; FS left, left hippocampal volume from FreeSurfer; SZ, probands with schizophrenia; SAD, probands with schizoaffective disorder; BDP, probands with psychotic bipolar I disorder.

aSample sizes are indicated per hippocampal volume measure.

bChlorpromazine equivalents were calculated for concomitant (taken during the study) antipsychotic medications according to Andreasen et al. 58

Statistically significant outcomes are indicated in Bold.

Correlations Between Manual Tracing and Semiautomated Hippocampal Outcomes

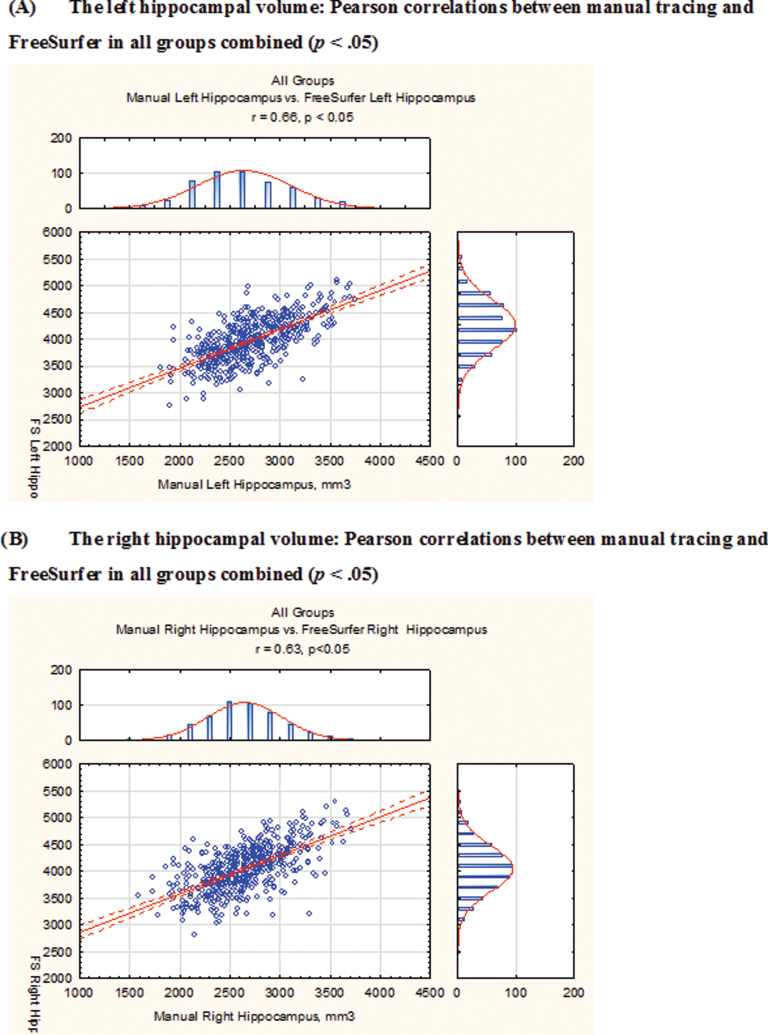

Direct, moderate to strong correlations were found between hippocampal volume outcomes from manual tracing and semiautomated parcellation (r = .51–.73, P < .05) across all proband, relative, and HC groups (figure 2). Manual tracing yielded lower bilateral hippocampal volumes than FreeSurfer: 31.46% and 34.58% volume differences for the left and right hippocampal ROIs, respectively, averaged across all study groups.

Fig. 2.

Pearson correlations between the hippocampal volume outcomes from the 2 ROI methodologies–manual tracing and FreeSurfer–in all study groups combined. Manual tracing yielded lower bilateral hippocampal volumes than FreeSurfer: left, manual tracing volume = 2721.38mm3, FreeSurfer = 3970.78mm3, 31.46% difference; right, manual tracing volume = 2645.51mm3, FreeSurfer = 4043.89mm3, 34.58% difference (all volumes are averaged across all study groups). Correlation coefficients (r) in: (1) All groups combined: left, r = .66; right, r = .63; (2) probands: SZ, left, r = .73; right, r = .63; SAD, left, r = .66; right, r = .74; BDP, left, r = .65; right, r = .64; (3) relatives: SZ-Rel, left, r = .68; right, r = .69; SZD-Rel, left, r = .6; right, r = .55; BDP-Rel, left, r = .72; right, r = .71; and (4) HC: left, r = .57; right, r = .51. All correlations are statistically significant at P < .05. SZ, probands with schizophrenia; SAD, probands with schizoaffective disorder; BDP, probands with psychotic bipolar I disorder; SZ-Rel, relatives of probands with schizophrenia; SAD-Rel, relatives of probands with schizoaffective disorder; BDP-Rel, relatives of probands with psychotic bipolar I disorder.

Discussion

This study examined hippocampal volume characteristics in probands and their first-degree relatives across the schizophrenia-bipolar psychosis dimension from a large multisite sample (B-SNIP) using 2 ROI methodologies: The “gold standard” manual tracing and FreeSurfer. The outcomes showed bilateral hippocampal volume reductions in SZ and SAD compared with controls, but normal bilateral hippocampal volumes in BDP. Hippocampal volumes in relatives contrasted by their probands’ diagnoses were normal, with no differences found between relatives with and without lifetime psychosis spectrum disorders. However, relatives’ subgroup analysis, where hippocampal outcomes in relatives were stratified by their respective probands’ volumes (ie, above and below group median), suggested a cosegregation of hippocampal volume outcomes in probands and relatives from the same pedigree: Relatives whose probands had “high” volumes also had “high” hippocampal volumes, whereas relatives whose probands had “low” volumes also showed “low” hippocampal volumes. These differences were strongest in BDP-Rel (left manual measure, P = .001) but were also observed in SZ-Rel (left manual, P = .051; right FreeSurfer, P = .052) and SAD-Rel (left manual, P = .068) at a trend level. Furthermore, hippocampal volume outcomes from the conventional manual tracing approach with rigorous reliability standards and semiautomated regional parcellation, FreeSurfer, correlated highly. Exploratory analyses revealed inverse correlations between hippocampal volume and PANSS psychosis and total scores, suggesting a relationship between the volume reduction and severity of psychosis. Direct correlations were obtained between hippocampal volume and BACS declarative memory and composite scores, suggesting a cognition cost to hippocampal volume reduction. Active treatment with antipsychotics had no effect on hippocampal volume outcomes, whereas lithium was associated with an increased hippocampal volume, albeit based on a single measure (right FreeSurfer, P = .047).

The divergent findings for hippocampal volume outcomes in schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder vs psychotic bipolar I disorder are in agreement with several prior reports,1,24,31,33 but not all.13,24,26 The volume decreases found in schizophrenia/schizoaffective cases are subtle, consistent with previously observed range of 2%–4% decrease based on meta-analyses;3,5 thus, larger samples may be necessary to detect these regional alterations. The mechanisms underlying these hippocampal volume differences across schizophrenia vs bipolar disorder phenotypes are unknown. Nevertheless, postmortem findings from schizophrenia and bipolar cases parallel these hippocampal characteristics captured with sMRI. Tissue from SZ cases show reductions in whole hippocampal volume compared with controls59,60 (although see).61,62 Decreased hippocampal volume may be due to reduced neuropil volume along with normal cell size and number, similar to Goldman-Rakic and Selemon’s63 observations in prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia. Furthermore, hippocampal subfield alterations have been reported in schizophrenia, suggesting subfield-specific disease vulnerability16: Cell size is decreased in the left cornu ammonis 1 (CA1) and CA2, and the right CA364; nonpyramidal cell size and density in CA2 were found to be decreased in a mixed schizophrenia/bipolar disorder sample.65 However, 2-dimensional cell counting studies carry methodological limitations due to tissue shrinkage by fixation and staining procedures.62 Additionally, problems may be caused by irregular cell shape and size (ie, pyramidal neurons), nonrandom orientation, and cutting of cells during sectioning.66 Stereological studies failed to detect alterations in the total cell number in CA1, CA2/3, CA4, or subiculum in schizophrenia cases vs matched controls.61,67 Nevertheless, a decreased oligodendrocyte number in the bilateral deep polymorph layer of the dentate gyrus/CA4 has been detected and linked to hippocampal volume decreases and white matter tracts alterations captured with in vivo imaging techniques.62 Postmortem findings in bipolar probands are even less consistent, with some studies reporting subtle hippocampal volume reductions compared with controls.68 Although the total number of hippocampal neurons is normal,69 size of pyramidal neurons in CA170 and nonpyramidal cell layer volume in CA2/369 were found to be decreased in bipolar cases vs HC. In contrast, some studies report no differences in neuronal densities in hippocampus, superior temporal cortex, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in bipolar vs controls tissue,71 consistent with the finding of overall normal cortical thickness in bipolar cases.72 These distinct postmortem findings in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, with volumetric/cellular reductions found in schizophrenia and less severe, if any, tissue volume changes in bipolar disorder,73 suggest at least partially unique anatomical underpinnings for the 2 disorders and provide plausible cellular correlates for the divergent hippocampal volume outcomes in SZ/SAD and BDP observed here.

Alternatively, it is possible that hippocampal volume preservation in BDP could be secondary to a medication effect (ie, chronic treatment with lithium) and that, even if a “primary” disease-associated loss of hippocampal volume exists in these probands, it could be obscured by a volume-enhancing effect of chronic exposure to lithium.32,33 Our findings of higher hippocampal volumes in probands actively treated with lithium vs those who were not support this notion, albeit the exploratory nature of these analyses merits cautious interpretation. Moreover, active treatment effects tested here could be obscured by high frequency of combined medication use (61%–81%) across all proband groups, as well as by longitudinal effects of both disease and treatments on hippocampal structure.74–78 Disambiguating disease and medication effects is difficult, especially in a cross-sectional study such as ours.

The finding of overall normal hippocampal volumes in biological relatives, when contrasted based on their probands’ diagnoses, is in agreement with some2,27,31,41,42 but not all25,35–39 reports. Hippocampal abnormalities in relatives may be even more subtle than in probands, possibly manifesting on functional rather than structural level, supported by well-established deficits in declarative memory in SZ-Rel, SAD-Rel, and BDP-Rel79–81; and correlations with BACS observed here. Our findings argue for disease effects that accompany psychosis in probands (eg, characteristic cellular abnormalities in SZ), which may be not present in relatives. Longitudinal MRI studies find hippocampal volume decreased in first-episode and chronic psychosis probands alike but not in ultrahigh-risk individuals,20 suggesting this biomarker’s specificity to frank, fully manifested psychosis within psychosis dimension. Subsequent exploratory analyses stratifying relatives’ hippocampal outcomes by volumes in their related probands suggest a consistent pattern of hippocampal outcomes within the same pedigrees: Relatives of probands with “low” hippocampal volumes had “low” volumes as well, whereas relatives of probands with “high” volumes had consistently “high” hippocampal outcomes. These findings indicate substantial heterogeneity within the relatives’ sample, with a range of heritable82 “hippocampal biomarker load,” clustering in probands and relatives within the same pedigree. These hippocampal volume characteristics do not map on either the DSM “schizophrenia/bipolar” or “psychosis spectrum disorders/unaffected” relatives diagnostic groups, and advocate for future studies testing heritability and genetic underpinnings for brain structure biomarkers.

Hippocampal outcomes from manual and semiautomated volumetric approaches showed direct, moderate to strong correlations (r = .51–.73, P < .05), consistent with previous studies.12,83 Nevertheless, these methodologies utilize entirely different volume-defining approaches, reflected in observed here differences in volumes (ie, lower volumes with manual tracing than FreeSurfer), similar to prior reports.12,83 Manual tracing remains a “gold standard” in ROI-focused investigations, providing precise regional definitions and is highly sensitive to within- and between-subject anatomical variabilities. It is especially useful in investigation of brain structures known to have significantly heterogeneous tissue intensity properties, eg, subcortical structures, as well as in hippocampal subfield-level analyses.84,85 However, this methodology requires rigorous reliability standards, high scan resolution, and ROI definition specificity, particularly in the hippocampus.51 FreeSurfer is semiautomated and therefore highly reproducible and more efficient in person hours, making it useful for large samples. However, region-specific inconsistencies in volume estimates have been reported with this technique, eg, less precision in anterior hippocampus,83 and overall larger/more inclusive hippocampal ROIs compared with manual tracing,12,83 accounted for by inclusion of areas avoidable during manual tracing (eg, subiculum/presubiculum, hippocampus-amygdala transitional zone). Nevertheless, the 2 methodologies show high correlations in volume estimates, and both are reliable and valid for volumetric analysis.

These findings from a large psychosis family sample (B-SNIP) support structural alterations in hippocampus as a putative biomarker for the 2 major psychosis phenotypes, schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, but not for psychotic bipolar I disorder. Both the “primary” disease effects, as demonstrated by postmortem schizophrenia vs bipolar tissue findings,63–65,68–70,72 and chronic treatments (eg, a volume-enhancing effect of lithium)32,33 likely contribute to these outcomes. Structural and functional hippocampal alterations, which are long known to play a crucial role in learning and memory processes,86 have been recently linked to psychosis formation,16 providing a framework for future testing of the biological mechanisms of psychosis. The strengths of our study are the relatively large sample, study of psychosis probands and their relatives across DSM psychosis diagnoses, and comprehensive hippocampal ROI characterization via 2 complimentary volumetric methodologies: The “gold standard” manual tracing and semiautomated parcellation by FreeSurfer. Limitations include the cross-sectional nature of the study, potential confounds related to chronic and active medication use (ie, only a small subset of probands were off-antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, and/or other psychotropic medications at the time of imaging acquisition), as well as state of illness. In addition, psychosis diagnoses are limited to schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and psychotic bipolar I disorder, and do not cover full psychosis spectrum or relevant nonpsychotic phenotypes (eg, nonpsychotic bipolar disorder). Future studies investigating brain structure characteristics in individuals with severe mental illness, using multimodal imaging techniques coupled with genetic and molecular testing, focusing on disease dimensions (eg, psychosis, affect, and cognition) and underlying circuitries may help to elucidate disease mechanisms and define disease biomarkers.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at http://schizophre niabulletin.oxfordjournals.org.

Funding

National Institute of Mental Health (MH077851 to C.A.T., MH078113 to M.S.K., MH077945 to G.D.P., MH077852 to G.K.T., MH077862 to J.A.S.); NARSAD/The Brain and Behavior Research Fund John Kennedy Harrison 2010 Young Investigator Award (17801 to E.I.I.); APF/Kempf Fund for Research Development in Psychobiological Psychiatry 2011 Award (C.A.T., E.I.I.). The NIMH, NARSAD/The Brain and Behavior Research, and APF/Kempf Fund had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Gunvant K. Thaker, MD, the former Director of the Schizophrenia Research Program at the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center, University of Maryland School of Medicine was closely involved with the conceptual and methodological aspects of the B-SNIP consortium. We tremendously appreciate his contribution, mentorship, and collaboration. We also would like to thank Myrna Wallace-Servera, MD, Siva Dantu, MD Candidate, Austin Hu, MD Candidate, and Morgan McConkey, BS, from UT Southwestern Medical Center, and Ian T. Mathew, BA from Harvard Medical School for their contributions to this study and the manuscript preparation. We also express appreciation for the many unnamed research staff members at each site, as well as patients and their families who contributed their effort to this research. This data were presented as a poster at the International Congress on Schizophrenia Research April 24, 2013. All authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study. S.J.M.A., E.I.I., T.A.G., A.P.R., H.J.-S., C.B.S., A.N.F., N.T., A.S.B., B.W., G.P., B.A.C., and M.S.K. report no financial disclosures. G.D.P. reports no potential conflicts of interest related to this manuscript. He reports the following financial disclosure: Bristol-Myers Squibb. J.A.S. reports no potential conflicts of interest related to this manuscript. He reports the following financial disclosures: (1) Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc., (2) Bristol-Myers Squibb, (3) Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, (4) F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Ltd, and (5) Eli Lilly and Company. C.A.T. reports no potential conflicts of interest related to this manuscript. She reports the following financial disclosures: (1) Acadia Pharmaceuticals—Ad Hoc Consultant, (2) American Psychiatric Association—Deputy Editor, (3) Astellas—Ad Hoc Consultant, (4) The Brain & Behavior Foundation—Council Member, (5) Eli Lilly Pharmaceuticles—Ad Hoc Consultant, (6) International Congress on Schizophrenia Research—Organizer, (7) Intra-cellular Therapies (ITI, Inc.)—Advisory Board, drug development, (8) Institute of Medicine—Council Member, (9) Lundbeck, Inc.—Ad Hoc Consultant, (10) NAMI—Council Member, (11) National Institute of Medicine—Council Member, and (12) PureTech Ventures—Ad Hoc Consultant.

References

- 1. Altshuler LL, Bartzokis G, Grieder T, et al. An MRI study of temporal lobe structures in men with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:147–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goldman AL, Pezawas L, Mattay VS, et al. Heritability of brain morphology related to schizophrenia: a large-scale automated magnetic resonance imaging segmentation study. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:475–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nelson MD, Saykin AJ, Flashman LA, Riordan HJ. Hippocampal volume reduction in schizophrenia as assessed by magnetic resonance imaging: a meta-analytic study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:433–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sim K, DeWitt I, Ditman T, et al. Hippocampal and parahippocampal volumes in schizophrenia: a structural MRI study. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:332–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wright IC, Rabe-Hesketh S, Woodruff PW, David AS, Murray RM, Bullmore ET. Meta-analysis of regional brain volumes in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:16–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Medoff DR, Holcomb HH, Lahti AC, Tamminga CA. Probing the human hippocampus using rCBF: contrasts in schizophrenia. Hippocampus. 2001;11:543–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heckers S, Rauch SL, Goff D, et al. Impaired recruitment of the hippocampus during conscious recollection in schizophrenia. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:318–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shohamy D, Wagner AD. Integrating memories in the human brain: hippocampal-midbrain encoding of overlapping events. Neuron. 2008;60:378–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Heckers S, Zalesak M, Weiss AP, Ditman T, Titone D. Hippocampal activation during transitive inference in humans. Hippocampus. 2004;14:153–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Weiss AP, Zalesak M, DeWitt I, Goff D, Kunkel L, Heckers S. Impaired hippocampal function during the detection of novel words in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:668–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shohamy D, Mihalakos P, Chin R, Thomas B, Wagner AD, Tamminga C. Learning and generalization in schizophrenia: effects of disease and antipsychotic drug treatment. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:926–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Doring TM, Kubo TT, Cruz LC, Jr, et al. Evaluation of hippocampal volume based on MR imaging in patients with bipolar affective disorder applying manual and automatic segmentation techniques. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;33:565–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Swayze VW, 2nd, Andreasen NC, Alliger RJ, Yuh WT, Ehrhardt JC. Subcortical and temporal structures in affective disorder and schizophrenia: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Biol Psychiatry. 1992;31:221–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Geuze E, Vermetten E, Bremner JD. MR-based in vivo hippocampal volumetrics: 2. findings in neuropsychiatric disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:160–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kasai K, Shenton ME, Salisbury DF, et al. Progressive decrease of left superior temporal gyrus gray matter volume in patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:156–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tamminga CA, Stan AD, Wagner AD. The hippocampal formation in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1178–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tamminga CA, Southcott S, Sacco C, Wagner AD, Ghose S. Glutamate dysfunction in hippocampus: relevance of dentate gyrus and CA3 signaling. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:927–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Knable MB, Barci BM, Webster MJ, Meador-Woodruff J, Torrey EF; Stanley Neuropathology Consortium. Molecular abnormalities of the hippocampus in severe psychiatric illness: postmortem findings from the Stanley Neuropathology Consortium. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:609–20, 544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Benes FM. Relationship of GAD(67) regulation to cell cycle and DNA repair in GABA neurons in the adult hippocampus: bipolar disorder versus schizophrenia. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:625–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Velakoulis D, Wood SJ, Wong MT, et al. Hippocampal and amygdala volumes according to psychosis stage and diagnosis: a magnetic resonance imaging study of chronic schizophrenia, first-episode psychosis, and ultra-high-risk individuals. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:139–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tamminga CA. Psychosis is emerging as a learning and memory disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tamminga CA, Ivleva EI, Keshavan MS, et al. Clinical phenotypes of psychosis in the Bipolar-Schizophrenia Network on Intermediate Phenotypes (B-SNIP). Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:1263–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Keshavan MS, Dick E, Mankowski I, et al. Decreased left amygdala and hippocampal volumes in young offspring at risk for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2002;58:173–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Strasser HC, Lilyestrom J, Ashby ER, et al. Hippocampal and ventricular volumes in psychotic and nonpsychotic bipolar patients compared with schizophrenia patients and community control subjects: a pilot study. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:633–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Van Erp TG, Saleh PA, Rosso IM, et al. Contributions of genetic risk and fetal hypoxia to hippocampal volume in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, their unaffected siblings, and healthy unrelated volunteers. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1514–1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pearlson GD, Barta PE, Powers RE, et al. Ziskind-Somerfeld Research Award 1996. Medial and superior temporal gyral volumes and cerebral asymmetry in schizophrenia versus bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;41:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Goghari VM, Macdonald AW, 3rd, Sponheim SR. Temporal lobe structures and facial emotion recognition in schizophrenia patients and nonpsychotic relatives. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:1281–1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ivleva EI, Bidesi AS, Thomas BP, et al. Brain gray matter phenotypes across the psychosis dimension. Psychiatry Res. 2012;204:13–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Karnik-Henry MS, Wang L, Barch DM, Harms MP, Campanella C, Csernansky JG. Medial temporal lobe structure and cognition in individuals with schizophrenia and in their non-psychotic siblings. Schizophr Res. 2012;138:128–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yang Y, Nuechterlein KH, Phillips OR, et al. Disease and genetic contributions toward local tissue volume disturbances in schizophrenia: a tensor-based morphometry study. Hum Brain Mapping. 2013;33:2081–2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McDonald C, Marshall N, Sham PC, et al. Regional brain morphometry in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder and their unaffected relatives. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:478–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Beyer JL, Kuchibhatla M, Payne ME, et al. Hippocampal volume measurement in older adults with bipolar disorder. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12:613–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kempton MJ, Geddes JR, Ettinger U, Williams SC, Grasby PM. Meta-analysis, database, and meta-regression of 98 structural imaging studies in bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:1017–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hirayasu Y, Shenton ME, Salisbury DF, et al. Lower left temporal lobe MRI volumes in patients with first-episode schizophrenia compared with psychotic patients with first-episode affective disorder and normal subjects. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1384–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McNeil TF, Cantor-Graae E, Weinberger DR. Relationship of obstetric complications and differences in size of brain structures in monozygotic twin pairs discordant for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:203–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Boos HB, Aleman A, Cahn W, Hulshoff Pol H, Kahn RS. Brain volumes in relatives of patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Suddath RL, Christison GW, Torrey EF, Casanova MF, Weinberger DR. Anatomical abnormalities in the brains of monozygotic twins discordant for schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:789–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bhojraj TS, Francis AN, Montrose DM, Keshavan MS. Grey matter and cognitive deficits in young relatives of schizophrenia patients. Neuroimage. 2011;54(suppl 1):S287–S292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Seidman LJ, Faraone SV, Goldstein JM, et al. Left hippocampal volume as a vulnerability indicator for schizophrenia: a magnetic resonance imaging morphometric study of nonpsychotic first-degree relatives. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:839–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Seidman LJ, Faraone SV, Goldstein JM, et al. Thalamic and amygdala-hippocampal volume reductions in first-degree relatives of patients with schizophrenia: an MRI-based morphometric analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:941–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Waldo MC, Cawthra E, Adler LE, et al. Auditory sensory gating, hippocampal volume, and catecholamine metabolism in schizophrenics and their siblings. Schizophr Res. 1994;12:93–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hajek T, Carrey N, Alda M. Neuroanatomical abnormalities as risk factors for bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7:393–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Noga JT, Vladar K, Torrey EF. A volumetric magnetic resonance imaging study of monozygotic twins discordant for bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2001;106:25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders/Patient Edition (SCID-I/P). New York, NY: New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research Department; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M. Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (SIDP). Iowa City, IA: Department of Psychiatry, University of Iowa; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Keefe RS, Goldberg TE, Harvey PD, Gold JM, Poe MP, Coughenour L. The Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia: reliability, sensitivity, and comparison with a standard neurocognitive battery. Schizophr Res. 2004;68:283–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hill SK, Reilly JL, Keefe RS, et al. Neuropsychological impairments in schizophrenia and psychotic bipolar disorder: findings from the Bipolar-Schizophrenia Network on Intermediate Phenotypes (B-SNIP) study. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:1275–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Konrad C, Ukas T, Nebel C, Arolt V, Toga AW, Narr KL. Defining the human hippocampus in cerebral magnetic resonance images–an overview of current segmentation protocols. Neuroimage. 2009;47:1185–1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Duvernoy H. The Human Brain: Surface, Blood Supply, and Three-Dimensional Sectional Anatomy. Second, Completely Revised and Enlarged Edition. 2nd ed. New York, NY: SpringerWien; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Dale AM, Fischl B, Sereno MI. Cortical surface-based analysis. I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. Neuroimage. 1999;9:179–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, et al. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron. 2002;33:341–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ségonne F, Dale AM, Busa E, et al. A hybrid approach to the skull stripping problem in MRI. Neuroimage. 2004;22:1060–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Francis AN, Seidman LJ, Jabbar GA, et al. Alterations in brain structures underlying language function in young adults at high familial risk for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;141:65–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York, NY: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Andreasen NC, Pressler M, Nopoulos P, Miller D, Ho BC. Antipsychotic dose equivalents and dose-years: a standardized method for comparing exposure to different drugs. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:255–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bogerts B, Meertz E, Schönfeldt-Bausch R. Basal ganglia and limbic system pathology in schizophrenia. A morphometric study of brain volume and shrinkage. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42:784–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bogerts B, Falkai P, Haupts M, et al. Post-mortem volume measurements of limbic system and basal ganglia structures in chronic schizophrenics. Initial results from a new brain collection. Schizophr Res. 1990;3:295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Walker MA, Highley JR, Esiri MM, et al. Estimated neuronal populations and volumes of the hippocampus and its subfields in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:821–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Schmitt A, Steyskal C, Bernstein HG, et al. Stereologic investigation of the posterior part of the hippocampus in schizophrenia. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;117:395–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Goldman-Rakic PS, Selemon LD. Functional and anatomical aspects of prefrontal pathology in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1997;23:437–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zaidel DW, Esiri MM, Harrison PJ. Size, shape, and orientation of neurons in the left and right hippocampus: investigation of normal asymmetries and alterations in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:812–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Benes FM, Kwok EW, Vincent SL, Todtenkopf MS. A reduction of nonpyramidal cells in sector CA2 of schizophrenics and manic depressives. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:88–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Williams RW, Rakic P. Three-dimensional counting: an accurate and direct method to estimate numbers of cells in sectioned material. J Comp Neurol. 1988;278:344–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Heckers S, Heinsen H, Geiger B, Beckmann H. Hippocampal neuron number in schizophrenia. A stereological study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:1002–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Bielau H, Trübner K, Krell D, et al. Volume deficits of subcortical nuclei in mood disorders A postmortem study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;255:401–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Konradi C, Zimmerman EI, Yang CK, et al. Hippocampal interneurons in bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:340–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Liu L, Schulz SC, Lee S, Reutiman TJ, Fatemi SH. Hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cell size is reduced in bipolar disorder. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2007;27:351–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Bielau H, Steiner J, Mawrin C, et al. Dysregulation of GABAergic neurotransmission in mood disorders: a postmortem study. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1096:157–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Selemon LD, Rajkowska G. Cellular pathology in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex distinguishes schizophrenia from bipolar disorder. Curr Mol Med. 2003;3:427–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Baumann B, Bogerts B. The pathomorphology of schizophrenia and mood disorders: similarities and differences. Schizophr Res. 1999;39:141–8; discussion 162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Lieberman JA, Tollefson GD, Charles C, et al. ; HGDH Study Group. Antipsychotic drug effects on brain morphology in first-episode psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Ho BC, Andreasen NC, Ziebell S, Pierson R, Magnotta V. Long-term antipsychotic treatment and brain volumes: a longitudinal study of first-episode schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:128–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Keshavan MS, Berger G, Zipursky RB, Wood SJ, Pantelis C. Neurobiology of early psychosis. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2005;48:s8–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Steen RG, Mull C, McClure R, Hamer RM, Lieberman JA. Brain volume in first-episode schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging studies. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:510–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Schmitt A, Weber S, Jatzko A, Braus DF, Henn FA. Hippocampal volume and cell proliferation after acute and chronic clozapine or haloperidol treatment. J Neural Transm. 2004;111:91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Hill SK, Harris MS, Herbener ES, Pavuluri M, Sweeney JA. Neurocognitive allied phenotypes for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:743–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Ivleva EI, Morris DW, Osuji J, et al. Cognitive endophenotypes of psychosis within dimension and diagnosis. Psychiatry Res. 2012;196:38–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Ivleva EI, Shohamy D, Mihalakos P, Morris DW, Carmody T, Tamminga CA. Memory generalization is selectively altered in the psychosis dimension. Schizophr Res. 2012;138:74–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Kaymaz N, van Os J. Heritability of structural brain traits an endophenotype approach to deconstruct schizophrenia. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2009;89:85–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Morey RA, Petty CM, Xu Y, et al. A comparison of automated segmentation and manual tracing for quantifying hippocampal and amygdala volumes. Neuroimage. 2009;45:855–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Mueller SG, Weiner MW. Selective effect of age, Apo e4, and Alzheimer’s disease on hippocampal subfields. Hippocampus. 2009;19:558–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Schobel SA, Lewandowski NM, Corcoran CM, et al. Differential targeting of the CA1 subfield of the hippocampal formation by schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:938–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Eichenbaum H, Sauvage M, Fortin N, Komorowski R, Lipton P. Towards a functional organization of episodic memory in the medial temporal lobe. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36:1597–1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Barnard J, Rubin DB. Small sample degrees of freedom with multiple imputation. Biometrika. 1999;86:948–955. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.