Abstract

Objective

To test whether bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) directly regulates differentiation of adult mouse ovary-derived oogonial stem cells (OSCs) in vitro.

Design

Animal study.

Setting

Research laboratory.

Animal(s)

Adult C57BL/6 female mice.

Intervention(s)

After purification from adult ovaries by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), OSCs were cultured without or with BMP4 in the absence or presence of the BMP4 antagonist, Noggin.

Main outcome measure(s)

Rates of in vitro-derived (IVD) oocyte formation and changes in gene expression were assessed.

Result(s)

Cultured OSCs expressed BMP receptor (BMPR) 1A (BMPR1A), BMPR1B and BMPR2, suggesting that BMP signaling can directly affect OSC function. In agreement with this, BMP4 significantly increased the number of IVD-oocytes formed by cultured OSCs in a dose-dependent manner, and this response was inhibited in a dose-dependent fashion by co-treatment with Noggin. Exposure of OSCs to BMP4 was associated with rapid phosphorylation of BMPR-regulated Smad1/5/8 protein, and this response was followed by increased expression of the meiosis initiation factors, stimulated by retinoic acid gene 8 (Stra8), muscle-segment homeobox 1 (Msx1) and Msx2. In keeping with the IVD-oocyte formation data, the ability of BMP4 to activate Smad1/5/8 signaling and meiotic gene expression in OSCs was abolished by co-treatment with Noggin.

Conclusion(s)

Engagement of BMP4-mediated signaling in adult mouse ovary-derived OSCs cultured in vitro drives differentiation of these cells into IVD-oocytes through Smad1/5/8 activation and transcriptional up-regulation of key meiosis-initiating genes.

Keywords: BMP4, oogenesis, oocyte, germ cells, stem cells

Introduction

Over the past several years, three different laboratories have independently isolated mitotically active germ cells from juvenile and adult mouse ovaries that can be propagated ex vivo (1–4), generate what appear to be oocytes in defined cultures in vitro (2, 4), and differentiate into fertilization-competent eggs after intraovarian transplantation in vivo (1, 4–6). These findings, coupled with identification of a comparable population of oocyte precursor cells in ovaries of reproductive age women (4), add strong support to claims made almost a decade ago that, contrary to longstanding beliefs in the field of reproductive biology (7), adult mammalian ovaries are capable of oocyte and follicle renewal (8). Adding to this, very recent gene expression profiling studies have shown that oogonial stem cells (OSCs) isolated from adult ovaries differ markedly from embryonic primordial germ cells (PGCs), indicating that these two populations of oocyte-producing germline stem cells in females are distinct entities (9). Although more experiments are needed to define the exact physiological contribution of these newly discovered cells to adult ovarian function and perhaps aging-related ovarian failure, the now large body of evidence from multiple laboratories supporting the existence and functionality of mammalian OSCs provides a strong impetus to characterize these cells more rigorously (reviewed in 10–12).

One approach to do this, which has proven extremely useful for exploration of mammalian spermatogonial stem cell biology (13, 14), is to establish and propagate OSCs under defined conditions ex vivo. In cultures of mouse or human OSCs, without any somatic feeder cell population, two groups have independently reported that the cells spontaneously differentiate into large spherical cells that have many characteristic features of oocytes (2, 4). Although these in vitro-derived (IVD) oocytes, having been formed without any instructive cues normally provided by ovarian somatic (granulosa) cells that are required for periodic meiotic arrest and proper imprinting, are in all likelihood not competent for fertilization or embryonic development, IVD-oocytes generated in OSC cultures nonetheless closely resemble endogenous oocytes in morphological appearance and oocyte-specific gene expression patterns (2, 4). In addition, IVD-oocytes formed by cultured mouse OSCs, when aggregated with dispersed ovaries of neonatal mice, interact with endogenous granulosa cells to form immature follicles in vitro (2). This outcome closely parallels that observed after injection of green fluorescent protein (GFP-expressing) OSCs – mouse or human – into adult ovarian tissue, in that GFP-positive oocytes formed from the OSCs become rapidly enclosed within histologically normal follicles composed of host granulosa cells (1, 4). In mice, follicles containing OSC-derived oocytes mature in vivo to release fertilization competent eggs at ovulation that produce viable embryos and offspring (1, 4–6), thus confirming the full developmental competency of the oocytes produced by these cells. Accordingly, cultured OSCs offer considerable potential as a model to systematically identify factors and pathways involved in promoting oocyte formation from primitive female germ cells.

Previous studies with mice have identified bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) as a key regulator of embryonic primordial germ cell (PGC) differentiation (15). Like other members of the transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) superfamily of proteins, BMPs activate signal transduction in target cells by binding to type-1 transmembrane receptors (BMP receptor 1A or 1B; BMPR1A or BMPR1B). Once ligand bound, BMPR1 heterodimerizes with the BMP type-2 receptor (BMPR2) to initiate phosphorylation-dependent activation of its intracellular effectors, Smad proteins 1, 5 and 8 (Smad1/5/8) (16–18). In turn, the actions of BMPs can be neutralized by a naturally-occurring antagonist termed Noggin, which binds to BMP4 and other family members with high affinity, thus preventing interaction of these ligands with their receptors (19).

The functional importance of BMP4 and components of its signal transduction pathway to PGC differentiation during embryonic gonad development have been documented using gene knockout mouse models. For example, Bmp4-null mutant embryos are deficient in PGC development (15), and other studies have shown that BMPR1 (20) and its signal transducers, Smad1 (21, 22) and Smad5 (23), are also essential for PGC formation. In addition, in-vitro studies of isolated PGCs (24) and fetal ovarian tissue organ cultures (25, 26) further support a role for BMP4 in PGC development, although these studies have described both positive and negative effects of BMP4 on germ cell differentiation.

In PGCs of human fetal ovaries, BMP4 has been shown to increase expression of muscle segment homeobox 2 (MSX2)(27), which has, along with its related gene family member MSX1, been tied to meiotic entry. In fetal mouse ovaries, both Msx1 and Msx2 are increased at the time of meiotic initiation, and BMP4 can directly elevate expression of both genes in cultured fetal mouse ovaries (28). Interestingly, ovaries of genetic-null mouse embryos lacking expression of both Msx1 and Msx2 contain fewer meiotic cells and exhibit reduced expression of stimulated by retinoic acid gene 8 (Stra8)(28), the latter of which is essential for meiotic initiation and progression in germ cells of both sexes (29–31). Based on this information, herein we used mice as a model system to test if BMP4 can drive differentiation of adult ovary-derived OSCs into IVD-oocytes, and if so whether the response of OSCs to BMP4 exposure involves activation of Smad1/5/8 signaling and key meiosis-initiation genes as downstream targets.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Wild-type female C57BL/6 mice at 2 months of age were obtained from Charles River Laboratories. All experimental procedures reported herein were reviewed and approved by the institutional animal care and use committee of Massachusetts General Hospital.

Isolation and culture of OSCs

Adult mouse ovary-derived OSCs were purified by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and established as actively dividing germ cell cultures without somatic feeder cells, as described previously (4, 32). For all experiments, cells at passage number 32-38 were used.

In vitro oogenesis assay

Cultured OSCs spontaneously generate IVD-oocytes for up to 3 days after passage, and the number of IVD-oocytes generated by a fixed number of OSCs seeded per well remains relatively constant over successive passages (4). Herein, 2.5 × 104 OSCs were seeded into each well of a 24-weII cell culture plate. After 24 hours of culture, the cells were exposed to vehicle, human recombinant BMP4 (R&D Systems), mouse recombinant Noggin (R&D Systems), or the two factors together for an additional 16 hours. This design was based on our prior studies showing that formation of IVD-oocytes in mouse OSC cultures peaks between 24 and 48 hours after passage, and then rapidly declines (4). Hence, OSCs would be exposed to the indicated experimental treatments at a time when oogenic potential is highest. The number of IVD-oocytes generated and released into the culture medium was then determined by direct visual counts under a microscope. To perform the counts, one-fifth of the 500-μl of culture medium per well was removed and assessed carefully under light microscopy to identify every IVD-oocyte present based on morphological criteria and size (ref. 4; see also Supplemental Fig. 1). The actual number of oocytes counted per sample was then multiplied by a correction factor of 5 to account for the remaining volume of medium in each well not analyzed (4). Comparative morphological and gene expression analyses of IVD-oocytes present in supernatants of vehicle-treated and BMP4-treated OSC cultures showed no discernible differences between the two groups (Supplemental Fig. 1).

OSC proliferation assay

Culture wells containing 2.5 × 104 OSCs were treated without and with 100 ng/mL BMP4, alone or in combination with 150 ng/mL Noggin, for 40 hours, after which the total number of OSCs present in each well were counted using a hemacytometer.

Gene expression analysis

Total RNA was isolated from cultured OSCs or oocytes using the RNeasy Plus Micro kit (Qiagen). Each indicated mRNA was then assessed by conventional or real-time (quantitative) reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays using Platinum Taq polymerase (Invitrogen) and, in the case of real-time PCR, SYBR green supermix (BioRad). Sequences of the forward and reverse primers used, along with GenBank accession numbers of the corresponding genes, are provided in Supplemental Table 1. All samples were measured in duplicate and the amplification efficiency of each transcript primer set was determined by running a standard curve. The relative abundance of each transcript was normalized to an endogenous reference gene (β-actin) and calculated (33).

Immunofluorescence analysis

For detection of BMPRs and Stra8 at the protein level, dispersed mouse OSCs were seeded onto glass coverslips coated with poly-L-lysine, cultured for 24 hours, rinsed with 1×-concentrated phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then fixed with 2% neutral-buffered paraformaldehyde for 45 min at room temperature. Following fixation, the cells were rinsed with PBS again, incubated in blocking buffer (Tris-buffered saline containing 1% normal goat serum and 1% bovine serum albumin) and then incubated with primary antibodies against BMPR1A (1:50 dilution, rabbit polyclonal SC-20736; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), BMPR1B (1:50, rabbit polyclonal SC-25455; Santa Cruz), BMPR2 (5 μg/ml dilution, rabbit polyclonal ab96826; Abcam) or Stra8 (1:100 dilution, rabbit polyclonal ab49602; Abcam) at 4 C overnight. Cells were washed 3 times with PBS (5 min each wash) before incubation with a 1:500 dilution of goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen). Coverslips were then washed 3 additional times with PBS and mounted onto slides using mounting medium containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories). Images were captured using a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-S inverted fluorescent microscope and SPOT imaging software (Diagnostic Instruments). Omission of primary antibody on separate coverslips containing fixed OSCs processed in parallel served as negative controls for primary antibody specificity, which showed no signal (data not shown).

Immunoblot analysis

Cells were washed with PBS, and proteins were harvested in Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent (M-PER; Pierce) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). Lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 14,000g for 15 min, denatured by boiling for 5 min, and then separated by SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide gels). Resolved proteins (30 μg of indicated sample per lane) were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, blocked and then incubated with primary antibodies against Smad1 (#9743; Cell Signaling Technology) or Phospho-Smad1/5/8 (#9611; Cell Signaling Technology) overnight at 4 C. The blots were washed and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1 hour, and peroxidase activity was then visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare). Blots were re-probed with primary antibody against β-actin (MS-1295-P; Neo Markers) to confirm equal sample loading per lane.

Data presentation and analysis

All experiments were independently replicated at least three times. Quantitative data representing the mean ± standard error of the means (SEM) of combined results from the replicate experiments were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's test. Significant differences between mean values were assigned at P < 0.05. Where appropriate, qualitative images representative of the PCR, immunofluorescence and immunoblotting outcomes are provided.

Results

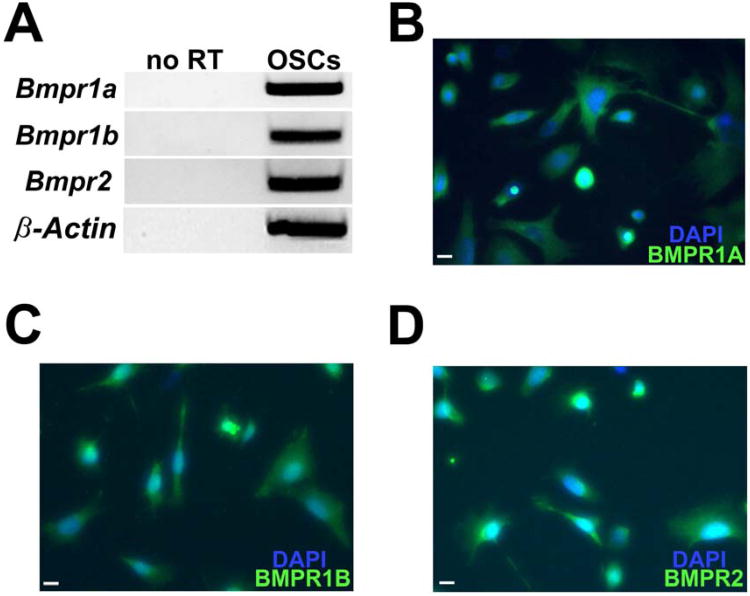

BMPRs are expressed in OSCs

To first determine if OSCs possess the machinery necessary to respond to BMP4 directly, we evaluated expression of BMPRs in cultured OSCs by RT-PCR and verified that mRNAs encoding BMPR1A, BMPR1B and BMPR2 were all detectable (Fig. 1A). Immunofluorescence was used to confirm that mRNAs encoding all three BMPRs were translated to their cognate proteins in OSCs (Fig. 1B–D).

Figure 1.

(A) Detection of Bmpr1a, Bmpr1b and Bmpr2 mRNAs in cultured OSCs (no RT, PCR analysis of RNA sample without reverse transcription used as a negative control to exclude genomic DNA contamination; β-actin, internal sample loading control). (B–D) Representative immunofluorescence-based detection of BMPR1A, BMPR1B and BMPR2 proteins (green) in cultured OSCs counterstained with DAPI (blue) to visualize nuclear DNA (scale bars, 10 μm).

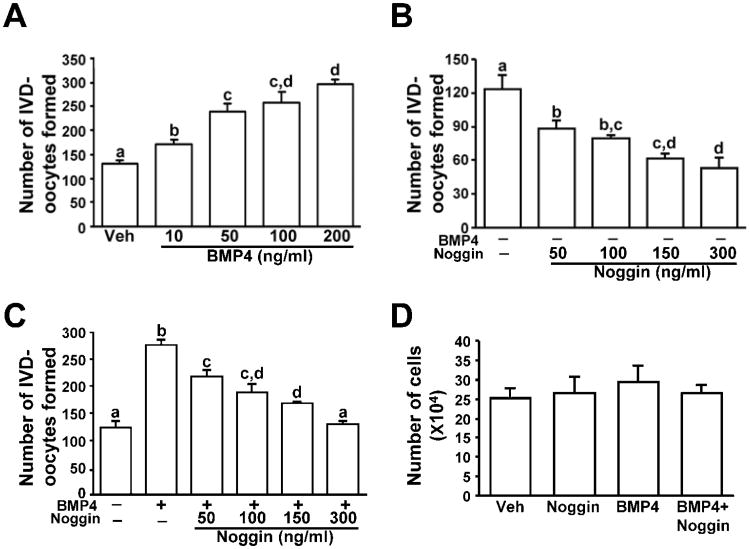

BMP4 enhances oogenesis

To determine if BMP4 directly regulates the oogenic potential of OSCs, we cultured OSCs with increasing concentrations of BMP4 (10–200 ng/mL) for 16 hours and then quantified the number of IVD-oocytes formed per well of 2.5 × 104 cells. The addition of recombinant BMP4 significantly increased the number of IVD-oocytes generated by OSCs in a dose-dependent manner, with a maximal two-fold increase observed at 100 ng/mL (Fig. 2A). Inclusion of the naturally occurring BMP4 antagonist, Noggin, in the culture medium reduced both basal (Fig. 2B) and BMP4-induced (Fig. 2C) IVD-oocyte formation rates in a dose-dependent manner. That Noggin suppressed basal rates of oogenesis likely reflects the presence of a low level of BMP4 in FBS, which is present in all culture wells. However, while the highest dose of Noggin completely abolished the BMP4-induced increase in IVD-oocyte formation over basal levels (Fig. 2C), the same dose of Noggin did not completely shut down basal oogenesis (Fig. 2B). This outcome indicates that IVD-oocyte formation is under the regulatory influence of factors other than BMP4 that are present in the OSC culture medium. In contrast to their effects on oogenesis, neither BMP4 nor Noggin affected OSC proliferation rates in vitro (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

(A–C) Effect of BMP4 and Noggin, alone (A, B) or in combination (C), on numbers of IVD-oocytes formed per well of 2.5 × 104 OSCs after 16 hours of treatment (mean ± SEM, n = 3–4 independent cultures; different letters, P < 0.05). (D) Lack of effect of BMP4 (100 ng/mL) and Noggin (150 ng/mL), alone or in combination, on proliferation of OSCs (2.5 × 104 cells initially seeded per well) over a 40-hour culture period (mean ± SEM, n = 4 independent cultures; no significant differences detected).

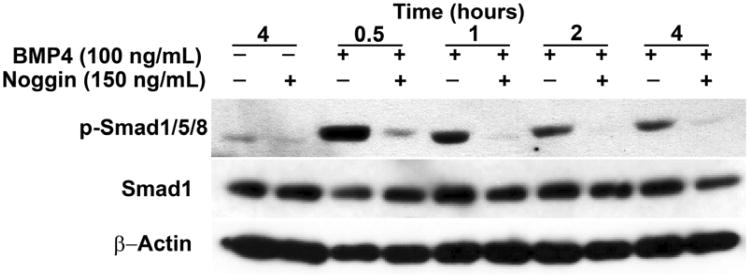

BMP4 activates Smad1/5/8 signaling in OSCs

Detection of BMPRs in OSCs (Fig. 1), combined with the oogenic response of OSCs to BMP4 stimulation (Fig. 2B), collectively indicate that Smad activation might be involved in transducing the actions of BMP4 in these cells. In support of this, we found that addition of recombinant BMP4 to OSC cultures induced phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8 without altering the overall level of total Smad1 protein (Fig. 3). Consistent with prior studies showing that phosphorylation of Smad proteins peaks 15–60 min after ligand-receptor–coupled activation and then fades away (34–36), BMP4-induced phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8 occurred within 0.5 hours and declined in a time-dependent manner over the next 3.5 hours (Fig. 3). Paralleling the blunted oogenic response of OSCs to BMP4 in the presence of Noggin (Fig. 2B), the activation of Smad1/5/8 in response to BMP4 was likewise inhibited by Noggin (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Representative immunoblot depicting the effect of BMP4 (100 ng/mL) and Noggin (150 ng/mL), alone or in combination, on Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation (p-Smad1/5/8) in wells of 5 × 104 OSCs after the indicated durations of treatment. Note that total Smad1 protein and β-actin protein levels remain comparable across treatment groups.

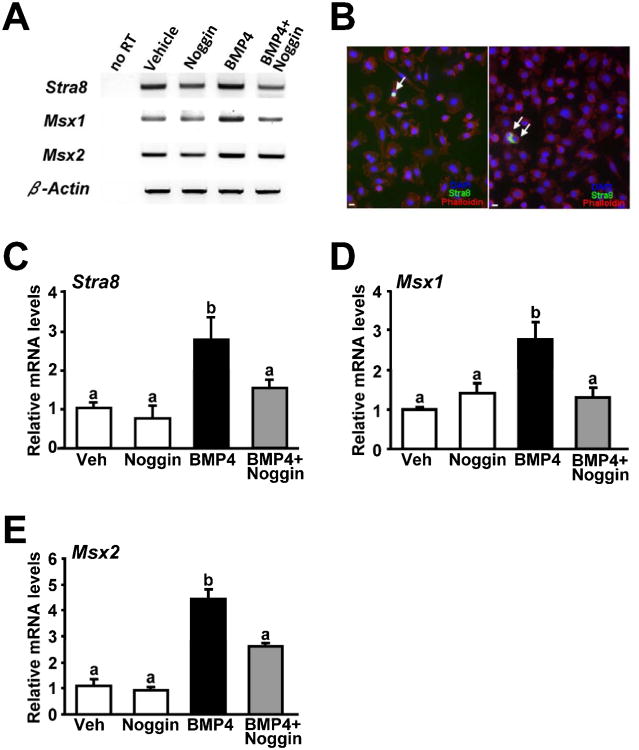

BMP4 induces meiotic gene expression in OSCs

We next explored if activation of BMP4-mediated signaling in OSCs, which enhanced IVD-oocyte formation (Fig. 2A), was tied to expression of genes required for meiotic initiation and progression in germ cells. Using conventional RT-PCR analysis, we detected expression of Stra8, Msx1 and Msx2 in cultured OSCs, and levels of all three genes appeared to vary in response to BMP4 and Noggin treatment (Fig. 4A). Immunofluorescence analysis confirmed the presence of OSCs expressing Stra8 protein in these cultures, albeit these cells were very rare (Fig. 4B). In agreement with results from others (37), Stra8 protein localization was nuclear in some germ cells (Fig. 4B, left) and cytoplasmic in other germ cells (Fig. 4B, right). The rarity of Stra8-positive cells is fully consistent with both a low percentage of IVD-oocytes being formed in these cultures (relative to the total number of OSCs seeded per well) and the transitory nature of detectable Stra8 protein in germ cells undergoing meiotic commitment and progression (29, 38). Through real-time RT-PCR analysis, we detected significant increases in the expression of Stra8, Msx1 and Msx2 in OSCs exposed to BMP4 (Fig. 4C–E). Like that observed for both oogenesis (Fig. 2B) and SMAD activation (Fig. 3), the ability of BMP4 to induce meiotic gene expression was repressed by the simultaneous presence of Noggin (Fig. 4C–E).

Figure 4.

(A) Conventional RT-PCR analysis of Stra8, Msx1 and Msx2 mRNA levels in OSCs (2.5 × 104 cells per well) treated for 24 hours without or with 100 ng/mL BMP4, alone or in combination with 150 ng/mL Noggin (no RT, PCR analysis of RNA sample without reverse transcription used as a negative control to exclude genomic DNA contamination; β-actin, internal sample loading control). (B) Representative examples of immunofluorescence-based detection of Stra8 protein (green, arrows) in cultured OSCs, counterstained with rhodamine phalloidin (red) and DAPI (blue) to visualize cytoplasmic F-actin and nuclear DNA, respectively (scale bars, 10 μm). (C–E) Real-time (quantitative) RT-PCR analysis of changes in Stra8 (C), Msx1 (D) and Msx2 (E) mRNA levels normalized to β-actin mRNA levels in OSCs (2.5 × 104 cells per well) treated for 24 hours without or with 100 ng/mL BMP4, alone or in combination with 150 ng/mL Noggin (mean ± SEM, n = 4 independent cultures; different letters, P < 0.05).

Discussion

The recent purification of oocyte-producing progenitor cells, capable of undergoing ex vivo expansion as well as of spontaneous differentiation into what appear to be oocytes in vitro, from adult ovarian tissue of mice and women (1–5) provides an unprecedented opportunity to systematically explore the external cues and intracellular signaling events that drive postnatal oogenesis in mammals (9–11). Although the IVD-oocytes produced by mouse or human OSCs in culture without influence from ovarian somatic (granulosa) cells are probably not competent for fertilization or embryogenesis (2, 4, 10), introduction of OSCs back into their natural microenvironment (viz. intraovarian transplantation) provides the necessary signals for these cells to generate oocytes that initiate de-novo folliculogenesis, mature, ovulate and fertilize to produce viable embryos and offspring (1, 4–6). Additionally, IVD-oocytes generated by OSCs in culture possess all of the morphological and gene expression profile characteristics of oocytes in vivo (4), interact with endogenous granulosa cells to form follicles in vitro (2) and, based on chromosomal DNA content analysis, appear to complete DNA reduction to the 1n stage in vitro (4). The responses of cultured OSCs to BMP4 exposure reported herein draw yet another parallel to female germ cell biology in vivo, the latter based on a growing body of work linking BMP4-mediated signal transduction to early PGC specification as well as PGC function in developing fetal ovaries (14, 20–25).

Importantly, in addition to facilitating analysis of downstream signals (Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation) and target genes (Stra8, Msx1 and Msx2) that are altered in female germ cells in response to BMP4 receptor activation, the use of cultured OSCs in these experiments offered us the unique advantage of measuring actual numbers of IVD-oocytes formed per unit of time from a set population of purified germ cells under defined conditions in vitro as a final readout. To our knowledge, this property of adult ovary-derived OSCs is not shared with embryonic ovary-derived PGCs maintained in vitro, which has limited extrapolation of results obtained with cultured PGCs in studies aimed at uncovering events capable of driving germ cell differentiation into oocytes using in vitro screening approaches. Although early meiotic events have been documented in cultured PGCs (39), efforts to quantify oocyte formation from these cells require, at least to this point, that fetal ovaries be used for analysis. In such a case, assessing the direct actions of a selected hormone or factor on oogenesis is complicated by the presence of a spectrum of additional factors being actively produced and secreted by somatic cells of the fetal gonads that influence PGC differentiation.

These experiments also highlight an interesting feature of OSCs cultured in vitro, which was reported previously (4) but not discussed in any detail, regarding the low but consistent percentage of OSCs that commit to form IVD-oocytes after each passage in vitro. For our assessment of changes in oogenic potential, approximately 2.5 × 104 OSCs are seeded into each culture well for experimental treatment. Of this number, less than 1% of the cells spontaneously differentiate into oocytes under basal culture conditions, and BMP4 stimulation results in a maximal 2-fold increase in the total number of oocytes produced. Although this change in oogenic output in response to BMP4 stimulation is significant, the vast majority of OSCs, cultured under identical conditions in the same wells, are refractory to meiotic commitment even in the presence of BMP4. Why this is the case remains unknown at present, but it may reflect the existence of intrinsic controls in each OSC that determines when during the lifespan a particular germ cell it is prepared to exit the mitotic cycle and commit to meiotic differentiation. In vivo, the process of asymmetric division of female Drosophila germline stem cells, which produces one daughter cell that remains self-renewing and a second daughter cell that undergoes differentiation to form an oocyte, is thought to involve differences in physical proximity of each daughter cell produced to niche-derived cues (40), including access to a gradient of BMP signaling (41). Such a control mechanism is likely not present in pure cultures of OSCs. This may indicate that decisions regarding self-renewal versus differentiation of adult stem/progenitor cells involve not only external (niche-derived) signals but also intrinsic cues, that latter of which can differ among individual cells.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1 (A) Morphology of in vitro-derived (IVD) oocytes generated by OSCs cultured without (vehicle, Veh) or with 100 ng/mL BMP4. (B) Comparative gene expression analysis of markers for germ cells (Ddx4) and oocytes (Ybx2, Nobox, Zp1, Zp2, Zp3, Gdf9) in IVD-oocytes collected from cultures of OSCs treated with vehicle (Veh) or 100 ng/mL BMP4 (no RT, PCR analysis of RNA sample without reverse transcription used as a negative control for genomic DNA contamination; β-actin, internal sample loading control).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Method to Extend Research in Time (MERIT) Award from the National Institute on Aging (NIH R37-AG012279 to J.L.T.), a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (NIH F32-AG034809 to D.C.W.), and a Glenn Foundation Award for Research in the Biological Mechanisms of Aging (J.L.T.).

Footnotes

E.S.P. has nothing to disclose; D.C.W. is a scientific consultant for OvaScience; J.L.T. has intellectual property described in U.S. Patents 7,195,775, 7,850,984, and 7,955,846, and is a cofounder of OvaScience.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Zou K, Yuan Z, Yang Z, Luo H, Sun K, Zhou L, et al. Production of offspring from a germline stem cell line derived from neonatal ovaries. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:631–6. doi: 10.1038/ncb1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pacchiarotti J, Maki C, Ramos T, Marh J, Howerton K, Wong J, et al. Differentiation potential of germ line stem cells derived from the postnatal mouse ovary. Differentiation. 2010;79:159–70. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zou K, Hou L, Sun K, Xie W, Wu J. Improved efficiency of female germline stem cell purification using Fragilis-based magnetic bead sorting. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:2197–204. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White YA, Woods DC, Takai Y, Ishihara O, Seki H, Tilly JL. Oocyte formation by mitotically active germ cells purified from ovaries of reproductive age women. Nat Med. 2012;18:413–21. doi: 10.1038/nm.2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Y, Yang Z, Yang Y, Wang S, Shi L, Xie W, et al. Production of transgenic mice by random recombination of targeted genes in female germline stem cells. J Mol Cell Biol. 2011;3:132–41. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjq043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park ES, Woods DC, White YAR, Tilly JL. Oogonial stem cells isolated from ovaries of adult transgenic female mice generate functional eggs and offspring following intraovarian transplantation. Reprod Sci. 2013;20(Supplement):75A–6A. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zuckerman S. The number of oocytes in the mature ovary. Rec Prog Horm Res. 1951;6:63–108. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson J, Canning J, Kaneko T, Pru JK, Tilly JL. Germline stem cells and follicular renewal in the postnatal mammalian ovary. Nature. 2004;428:145–50. doi: 10.1038/nature02316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imudia AN, Wang N, Tanaka Y, White YAR, Woods DC, Tilly JL. Comparative gene expression profiling of adult mouse ovary-derived oogonial stem cells supports a distinct cellular identity. Fertil Steril. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013/06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woods DC, Tilly JL. The next (re)generation of human ovarian biology and female fertility: is current science tomorrow's practice? Fertil Steril. 2012;98:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woods DC, White YAR, Tilly JL. Purification of oogonial stem cells from adult mouse and human ovaries: an assessment of the literature and a view toward the future. Reprod Sci. 2013;20:7–15. doi: 10.1177/1933719112462632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woods DC, Tilly JL. An evolutionary perspective on female germline stem cell function from flies to humans. Semin Reprod Med. 2013;31:24–32. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1331794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Miki H, Inoue K, Ogonuki N, Toyokuni S, Ogura A, et al. Long-term culture of mouse male germline stem cells under serum- or feeder-free conditions. Biol Reprod. 2005;72:985–91. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.036400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oatley JM, Brinster RL. The germline stem cell niche unit in mammalian testis. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:577–95. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawson KA, Dunn NR, Roelen BA, Zeinstra LM, Davis AM, Wright CV, et al. Bmp4 is required for the generation of primordial germ cells in the mouse embryo. Genes Dev. 1999;13:424–36. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.4.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balemans W, Van Hul W. Extracellular regulation of BMP signaling in vertebrates: a cocktail of modulators. Dev Biol. 2002;250:231–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoodless PA, Wrana JL. Mechanism and function of signaling by the TGF beta superfamily. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1998;228:235–72. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-80481-6_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Massague J. TGFβ signaling in context. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:616–30. doi: 10.1038/nrm3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zimmerman LB, De Jesus-Escobar JM, Harland RM. The Spemann organizer signal noggin binds and inactivates bone morphogenetic protein 4. Cell. 1996;86:599–606. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Sousa Lopes SM, Roelen BA, Monteiro RM, Emmens R, Lin HY, Li E, et al. BMP signaling mediated by ALK2 in the visceral endoderm is necessary for the generation of primordial germ cells in the mouse embryo. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1838–49. doi: 10.1101/gad.294004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayashi K, Kobayashi T, Umino T, Goitsuka R, Matsui Y, Kitamura D. SMAD1 signaling is critical for initial commitment of germ cell lineage from mouse epiblast. Mech Dev. 2002;118:99–109. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00237-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tremblay KD, Dunn NR, Robertson EJ. Mouse embryos lacking Smad1 signals display defects in extra-embryonic tissues and germ cell formation. Development. 2001;128:3609–21. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.18.3609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang H, Matzuk MM. Smad5 is required for mouse primordial germ cell development. Mech Dev. 2001;104:61–7. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00367-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pesce M, Gioia Klinger F, De Felici M. Derivation in culture of primordial germ cells from cells of the mouse epiblast: phenotypic induction and growth control by Bmp4 signalling. Mech Dev. 2002;112:15–24. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00624-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dudley BM, Runyan C, Takeuchi Y, Schaible K, Molyneaux K. BMP signaling regulates PGC numbers and motility in organ culture. Mech Dev. 2007;124:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ross AJ, Tilman C, Yao H, MacLaughlin D, Capel B. AMH induces mesonephric cell migration in XX gonads. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;211:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Childs AJ, Kinnell HL, Collins CS, Hogg K, Bayne RA, Green SJ, et al. BMP signaling in the human fetal ovary is developmentally regulated and promotes primordial germ cell apoptosis. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1368–78. doi: 10.1002/stem.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Le Bouffant R, Souquet B, Duval N, Duquenne C, Herve R, Frydman N, et al. Msx1 and Msx2 promote meiosis initiation. Development. 2011;138:5393–402. doi: 10.1242/dev.068452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baltus AE, Menke DB, Hu YC, Goodheart ML, Carpenter AE, de Rooij DG, et al. In germ cells of mouse embryonic ovaries, the decision to enter meiosis precedes premeiotic DNA replication. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1430–4. doi: 10.1038/ng1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koubova J, Menke DB, Zhou Q, Capel B, Griswold MD, Page DC. Retinoic acid regulates sex-specific timing of meiotic initiation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2474–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510813103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson EL, Baltus AE, Roepers-Gajadien HL, Hassold TJ, de Rooij DG, van Pelt AM, et al. Stra8 and its inducer, retinoic acid, regulate meiotic initiation in both spermatogenesis and oogenesis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:14976–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807297105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woods DC, Tilly JL. Isolation, characterization and propagation of mitotically active germ cells from adult mouse and human ovaries. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:966–88. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou Q, Heinke J, Vargas A, Winnik S, Krauss T, Bode C, et al. ERK signaling is a central regulator for BMP-4 dependent capillary sprouting. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;76:390–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang G, Matsuura I, He D, Liu F. Transforming growth factor-β-inducible phosphorylation of Smad3. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:9663–73. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809281200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galvin KE, Travis ED, Yee D, Magnuson T, Vivian JL. Nodal signaling regulates the bone morphogenic protein pluripotency pathway in mouse embryonic stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:19747–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.077347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tedesco M, La Sala G, Barbagallo F, De Felici M, Farini D. STRA8 shuttles between nucleus and cytoplasm and displays transcriptional activity. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:35781–93. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.056481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Menke DB, Koubova J, Page DC. Sexual differentiation of germ cells in XX mouse gonads occurs in an anterior-to-posterior wave. Dev Biol. 2003;262:303–12. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00391-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farini D, Scaldaferri ML, Iona S, La Sala G, De Felici M. Growth factors sustain primordial germ cell survival, proliferation and entering into meiosis in the absence of somatic cells. Dev Biol. 2005;285:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen S, Wang S, Xie T. Restricting self-renewal signals within the stem cell niche: multiple levels of control. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2011;21:684–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xia L, Zheng X, Zheng W, Zhang G, Wang H, Tao Y, Chen D. The niche-dependent feedback loop generates a BMP activity gradient to determine germline stem cell fate. Curr Biol. 2012;22:515–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1 (A) Morphology of in vitro-derived (IVD) oocytes generated by OSCs cultured without (vehicle, Veh) or with 100 ng/mL BMP4. (B) Comparative gene expression analysis of markers for germ cells (Ddx4) and oocytes (Ybx2, Nobox, Zp1, Zp2, Zp3, Gdf9) in IVD-oocytes collected from cultures of OSCs treated with vehicle (Veh) or 100 ng/mL BMP4 (no RT, PCR analysis of RNA sample without reverse transcription used as a negative control for genomic DNA contamination; β-actin, internal sample loading control).