Abstract

We examined the prevalence of emotional and behavioral problems and associated risk and protective factors among children and adolescents ages 6 to 18 years reared in orphanages in Turkey (n = 461, 87.9% of all eligible subjects) compared with a nationally representative community sample of similarly-aged youngsters brought up by their own families (n = 2280). Using the 90th percentile as the cut-off criterion, it was found that the Teacher’s Report Form (TRF) Total Problem score was higher for children and adolescents in orphanage care than in the community (23.2%, orphanage v. 11%, community). Multiple regression models explained 73% of the total variance of TRF Total Problems score for children and adolescents in orphanages. Regular contact with parents or relatives, between classroom teachers and orphanage staff, appropriate task involvement, perceived social support and competency were significant protective factors against emotional and behavioral problems. Younger age at first admission, being small for age, and feelings of stigmatization were associated with higher TRF Problem Scores (P<.05). Parental psychiatric disorder was unrelated to emotional and behavioral problems in children reflecting that psychosocial adversity and parenting problems in of themselves lead to institutionalization, irrespective of identifiable parental mental disorder. The findings are interpreted in the light of an urgent need for development of early intervention programs that promote community care of children by preventing separation from families, provision of support services for families in need, and development of counseling programs to prevent abandonment, abuse and neglect. Finding ways for child welfare professionals to collaborate more closely with early intervention programs would also increase the viable opportunities and rights of children and adolescents currently cared for in the system. Finally, alternative cost-effective care models need to be promoted including foster care or adoption systems and family based homes in the community.

Keywords: Orphanage, TRF, Prevalence, Behavioral and emotional problems, Risk and protective factors

1. Introduction

Over the past 65 years, developmental studies have shown that children and adolescents reared in institutional care settings exhibit higher than expected externalizing behavioral problems such as hyperactivity, aggression, anti-social behavior as well as internalizing emotional difficulties that include depression, anxiety, and emotional dysregulation (Ellis, Fisher, & Zaharie, 2004; Goldfarb, 1943; Maclean, 2003; McCann, James, Wilson, & Dunn, 1996; Roy, Rutter, & Pickles, 2000; Rushton & Minnis, 2002; Spitz, 1951; The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2005; Tizard & Hodges, 1978; Vorria, Wolkind, Rutter, Pickles, & Hobsbaum, 1998; Wolff & Fesseha, 1998). Although, to date, research has highlighted the negative global impact of institutional care on the development of youngsters, there is less documentation on the effects of risk and protective factors and the variability in mental health outcomes. A number of studies indicate that specific risk factors are associated with greater or lesser disruption to a child’s development. Why children who have experienced such early deprivation develop diverse types of symptoms and outcomes remains less well understood. There is also paucity of research from developing countries on this important topic.

Researchers define competence as a means of successfully achieving developmental tasks that are considered normative for a particular age and environmental context (Garmezy & Masten, 1991; Masten & Coatsworth, 1995, 1998). In this regard, protective factors have been examined in two ways: additive models and interactive models. With respect to additive models, protective factors are said to exhibit main or compensatory effects with the presence of a risk factor directly increasing the likelihood of a negative outcome and the presence of a protective factor directly increasing the likelihood of a positive outcome (Luthar, 1991; Masten, 1987; Pellegrini, 1990). On the other hand, in terms of interactive models, protective factors have effects only in combination with risk factors (Masten, 1987); the protective factors serving as internal and external resources that modify or buffer the impact of risk factors (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000; Rutter, 1987). Three broad categories of protective variables have been found to promote resilience in childhood (Garmezy, 1985). The first refers to the individual dispositional attributes, including temperamental factors, social orientation and responsiveness to change, cognitive abilities, and coping skills. The second general category of protective factors is related to the family milieu. A positive relationship with at least one parent or parental figure serving an important protective function. Other important family variables include cohesion, warmth, harmony, supervision, and absence of neglect. Finally, the third category of protective influences in childhood encompasses the attributes of the extrafamilial social environment. These include the availability of external resources and extended social supports as well as an individual’s use of such resources. The two most prominent predictors of resilience throughout childhood and adolescence include: strong pro-social relationship with at least one caring adult; and good intellectual capabilities (Masten & Coatsworth, 1998; Rutter, 1990; Werner & Smith, 1982).

An examination of the association among different developmental, environmental and social risk and protective factors in institutionalized children could add to our knowledge base regarding the manner in which deprivation affects mental health. Findings from studies of children and adolescents in orphanage care provide invaluable information that can inform theory, research, social policy, and preventive and therapeutic bio–psycho–social interventions with respect to both normal and atypical development.

According to the 2000 census, 38.4% of the Turkish population were aged 18 or less. As per records of the Turkish Social Services General Directorate in December, 2005, there were approximately 20,000 children and adolescents in the age group 0–18 living in orphanage care (General Directorate of Social Services, 2005). About 92% of these youngsters were placed in institutions, 4% in foster care, and a small number had been adopted, often by extended family. Besides the lack of foster care and adoption services as a matter of social policy, the reasons for the increasing number of children being placed in institutional care in Turkey include: the continuing financial inability of parents to care for a child and lack thereof of parenting skills to care for children; parental unwillingness to rear a child with frank disabilities; and loss of parental rights because of abuse and/or neglect. The orphanages represent a form of local employment and have been bureaucratically maintained. The children in orphanage care in Turkey are currently in the forefront of political interest due to the poor conditions of some institutions. The General Directorate of Social Services and the Child Protection Agency remain responsible for entrusting to the care of the State by means of court mandates. The Social Services and Child Protection Agency Law of 1983 stresses the availability of preventive social work at a general and community level and encourages family supports and other alternatives to prevent placing children under State care. Furthermore, according to the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), to which Turkey is a signatory, if it is necessary to remove a child from his or her family, then placement in foster or adoptive families is noted to be preferable to institutional care. Nevertheless, orphanage care has been maintained as the most common form of placement in the country and it is therefore not surprising that with the advent of increasing number of institutionalized youth there is a need for urgent policy change.

Although childhood through adolescence are critical developmental periods, to our knowledge, no prior representative national or international survey was sought to obtain detailed assessments of mental health problems in the country. In this study, we determined the prevalence of emotional and behavioral problems as reported by teachers of a representative sample children and adolescents ages 6 to 18 years compared to national representative community sample of similar ages. The resulting data was analysed in term of the patterns of associations between risk and protective factors as well as behavioral and emotional problems.

2. Research design and methods

2.1. Sample

Currently approximately 17,000 children ages 6 to 18 years live in various orphanages across the country under the auspices of the Social Services and Child Protection Administration (the Turkish acronym is SHCEK) under the Prime Ministry in Ankara. All the orphanages across various metropolitan centers are administered by the SHCEK having a minimum of 85 and a maximum of 400+ children divided into wards or residential units of approximately 15 to 24 occupants. A typical such ward might consist of a setup that includes a sleeping room, a living room and bathroom. Each orphanage has a director, who is generally a teacher or a social worker; there are additional staff including a social worker, a psychologist, nurses, caregivers, and office staff.

The teacher surveys were completed with the permission of the Social Services and Child Protection Administration who have jurisdiction over the children. The aim of the orphanage study was to reach 461 children and adolescents (95% confidence level; 384*1.2 ‘design effect’) using the probability cluster sampling method. The random sample consisted of 405 children (163 boys, 187 girls) (87.9% of those eligible) ages 6 to 18 years living in eight orphanages for healthy children (under the State Social Services and Child Welfare General Directorate) located in four different geographical areas. In each institution the number of subjects ranged from 33 to 48 given the total number of children across eight settings. The criteria for selection for the orphanage included: in good physical health, absence of mental retardation (intellectual disability); and residence in orphanage for at least 1 year.

The 2280 children who were from national representative sample and served as the control group (Erol & Simsek, 2000). The criteria for selection for the community sample also included: good physical health and absence of mental retardation (intellectual disability); and residence in the community or at least 1 year.

After random selection, school lists were prepared for each child by using the child’s school record. All the index children’s classroom teachers were identified and visited at school after lessons or during a free break session; the response rates for survey completion were: orphanage, 87.9%; community, 87.7%.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Teacher report form (TRF)

The TRF was selected for the study as among the three informants of child behaviors they are better correlated with nearly all other informants than parent or foster caregivers’ reports (Randazzo, Landsverk, & Ganger, 2003). First published by Achenbach and Edelbrock (1986) and revised in 2001 (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001), the TRF has been translated into more than 20 languages. The 2001 edition, designed for ages 6 to 18 has 118 specific problem items, plus 2 open-ended problem items, all of which are rated as 0=not true (as far as you know); 1=somewhat or sometimes true; and 2=very true or often true. Ratings of TRF problem items are based on the student’s functioning over the preceding 2 months.

The TRF yields problem scores at four levels of a scoring hierarchy (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). At the lowest level of the hierarchy are the 118 specific problem items. Next, the hierarchy contains eight syndromes derived by exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis: Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawn/Depressed (formerly called Withdrawn), Somatic Complaints, Social Problems, Thought Problems, Attention Problems, Rule-Breaking Behavior (formerly called Delinquent Behavior), and Aggressive Behavior). At the next level, are the Internalizing and Externalizing scales, derived from second-order factor analyses of the eight syndromes. The Internalizing scale consists of Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawn/Depressed, and Somatic Complaints syndromes comprise the Internalizing scale, whereas the Rule-Breaking Behavior and Aggressive Behavior syndromes, and the Externalizing scale comprises Rule-Breaking Behavior and Aggressive Behavior syndromes. The eight syndromes and the Internalizing and Externalizing scales are scored by summing their constituent items. The Total Problems scale, at the top of the hierarchy, the sum of the scores on all problem items.

The TRF also features DSM-oriented scale in addition to empirically based scales. Scales were constructed for the following 5 DSM-oriented categories: Affective Problems, Anxiety Problems, Somatic Problems, Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Problems, Oppositional Defiant Problems and Conduct Problems (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). The TRF has been used in over 500 published studies (Berube & Achenbach, 2004) and its validity and reliability are well documented (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001).

Competencies were measured by using The TRF Adaptive Functioning scale scores for performance in academic subjects, which teachers rate on a scale of 1 to 5 from far below grade to far above grade; the adaptive characteristics of working hard, behaving appropriately, learning, and being happy, which teachers rate on scales of 1 to 7 from much less to much more, compared to typical pupils of the same age; and the sum of the scores for the four adaptive characteristics, which can range from 4 to 28. To evaluate children’s adaptive functioning, teachers are asked to rate performance in academic subjects and the following adaptive characteristics: how hard is he/she working?; how appropriately is he/she behaving?; how much is he/she learning?; and how happy is he/she?

The TRF was translated into the Turkish with a second translation and back-translation procedure being followed. The test–retest reliability of the Turkish form is .88 for Total Problems and the internal consistency was also adequate (Cronbach alpha=.87) (Erol & Simsek, 2000). Internal consistency for the Total Problem was acceptable using the baseline sample from the present study (α=.84). Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to test the measurement structure of TRF scores. To study the applicability of the TRF syndromes in U.S. to the Turkish samples, the same statistical procedures were applied as described by De Groot, Koot, and Verhulst (1996) and Dumenci, Erol, Achenbach, and Simseck (2004). There was an evaluation of the goodness-of-fit between the data and the factor models by computing the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) which was .07.

2.2.2. Multidimensional scale of perceived social support (MSPSS)

The MSPSS has 12 items that assess perceived adequacy of support from the family, from a significant other, and from friends (Zimet, Dahlen, Zimet, & Farley, 1988). Ratings are made on a 7-point scale ranging from (1)“very strongly disagree” (7) to “very strongly agree”. The scale is a reliable and well-validated measure (Kazarian & McCabe, 1991; Zimet et al., 1988). This inventory was adapted into Turkish by Eker and Arkar (1995) with reliability and validity coefficients comparable to original values.

2.2.3. Child socio-demographic information form

The information form data was obtained from the records of each child in orphanage care. The questionnaire was designed to capture basic socio-demographic information, as well as risk and protective factors thought to influence problem behaviors. This included information on the socio-demographic background of the children such as age, gender, age of orphanage admission, contact with parents or relatives during care, status on having siblings in the same orphanage, reason for admission, care before admission to current institutions, mental health of parents, school variables including appropriate task involvement, characteristics of close friends, contact between teachers and orphanage staff, and the feeling of stigmatization.

2.3. Data analyses

The Social, Thought, Attention Problem, Internalizing, Externalizing scores, and Total Problem were used as continue variables in the analyses. Chi-square and t test were performed using the missing versus the not missing indicator as the grouping variables, and compare groups (orphanage and community sample). A univariate ANOVA were run to see if there were differences in behavioral outcomes based on gender and age groups of the orphanage and community sample. Bivariate correlational analyses were used to begin to examine relationships between risk and protective factors and behavioral problems.

Predictive factors were included in the subsequent models if they were significantly associated at the P<.05 level with any outcome variable in the bivariate analysis. Multiple regression models of outcome were estimated to determine independent associations of these protective and risk factors with the problem behaviors. With the TRF Total Problem score as the dependent variable, the following variables were tested: a) child gender (dummy coded: 0=girls; 1=boys); b) reason for admission (dummy coded: 0=family disruption, poverty; 1=abused); c) situation of parents (dummy coded: 0=parents are living; 1=unknown or died); d) contact with parents or relatives (dummy coded: 0=yes; 1=no); e) moves between institution (dummy coded: 0=more than two; 1=no or only one); f) contact with parents/relatives (dummy coded: 0=no; 1=yes); g) regular relation between classroom teacher and orphanage staff (dummy coded: 0=no; 1=yes); h) involved task work (dummy coded: 0=no; 1=yes); i) characteristics of close friends (dummy coded: 0=negative; 1=positive); and j) stigmatization (dummy coded: 0=no; 1=yes). Age, age at first admission, and competency were entered as continuous variables. All independent variables were entered simultaneously. These models fit the Durbin–Watson analysis and linear models according to F analysis.

To calculate the Total Problem prevalence, the cut-off criteria was based on the 90th percentile of the representative distributions of teacher-reported scores of deviant behavior (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 11.5).

3. Results

3.1. Description of samples

The orphanage group consisted of 180 boys (44.4%) and 225 girls (55.6%), the community sample consisted of 1222 boys (53.6%) and 1058 girls (46.4%). The mean age was 11.5±3.1 in orphanage group, 11.1± 3.0 in community sample. There were no significant differences in the mean ages and gender distribution of the orphanage care and family care children (P>.05).

About 72% of the children from a stable family background had been admitted to a unit primarily because of family disruption, parental separation or divorce (71.7%), poverty (13.2%), and 6.9% were illegitimate, 5.4% of the children were admitted because of physical or sexual abuse. Nearly 75% of the children had been admitted to the orphanage at school age (the mean admission age was 6.6±3). Duration at this institution was 39.8±31.1 months. 77.1% of children had lived with their own parents, 7.4% had lived with their relatives before admission and 15.6% had lived in another orphanages. The majority of the children (74.8%) had been transferred between institutions. The great majority of the children (66.4%) had siblings in the same placement.

Almost 68.9% of the children had mother or father, or both. Parental psychiatric disorder was assessed from case records compiled at the time of the children’s admission into the orphanage; 22.9% of these parents had been a history of mental disorder. Nearly 70% of the children continued to have regular contact with their parents or close relatives, seeing them and spending vacations with them or having telephone contact with them.

According to the interviews with their classroom teachers, teachers reported that orphanage staff did not participate in school meetings (22.8%). Another important finding was that 5% of the children had been stigmatized by their classroom friends or families.

3.2. Comparison of behavioral and emotional problems in orphanage care and in community groups

3.2.1. Mean scores and items

Table 1 presents the TRF reported behavioral problem scores according to gender and age for the orphanage care compared to the community samples (Erol & Simsek, 2000). Children in orphanage care had higher scores on all empirically based scales as well as on DSM-oriented scales with the exception of Anxious/Depressed and Somatic Complaints subscales (P<.05). There were statistically significant differences between the mean scores for the gender and age groups according to the orphanage and community samples on all empirically based scales as well as on DSM-oriented scales. Specifically, the younger orphanage boys had the highest scores on Anxious/Depressed, Social Problems, Thought Problems, Attention Problems, Rule-Breaking Behavior, Aggressive Behavior subscales, Internalizing, Externalizing and Total Problem scales, and all DSM-oriented scales except Somatic Problems (P<.05). On the other hand, the orphanage care older female group also had the highest scores on Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawn/Depressed subscales, Internalizing and Total Problem scores on TRF, and Affective Problems, Anxiety Problems on DSM-oriented scales (P<.05).

Table 1.

Mean scores of emotional and behavioral problems according to the orphanage care and community sample for the TRF

| Scales N | Orphanage sample | Community sample | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Orphans | Community | |||||

| 6–11 | 12–18 | 6–11 | 12–18 | 6–11 | 12–18 | 6–11 | 12–18 | 6–18 | 6–18 | |

| (128) | (52) | (107) | (118) | (734) | (488) | (660) | (398) | (405) | (2280) | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Empirically based | ||||||||||

| Anxious/Depressed | 5.7 (4.9)* | 4.5 (4.4) | 4.7 (3.9) | 6.9 (4.7)* | 5.3 (4.1) | 5.0 (3.8) | 5.9 (4.1) | 5.9 (4.4) | 5.6 (4.6) | 5.5 (4.1) |

| Withdrawn/Depressed | 4.1 (3.7) | 3.5 (3.6) | 3.2 (3.5) | 4.4 (3.8)* | 2.7 (3.1) | 2.9 (2.8) | 2.8 (2.9) | 2.9 (2.9) | 3.9 (3.6)* | 2.8 (2.9) |

| Somatic Complaints | .9 (1.9) | .8 (1.8) | .9 (1.8) | 1.2 (1.9) | .8 (1.7) | .7 (1.7) | .9 (1.8) | .8 (1.6) | .9 (1.9) | .8 (1.7) |

| Social Problems | 3.8 (3.8)* | 2.1 (2.7) | 2.6 (2.9) | 2.7 (2.9) | 2.4 (2.8) | 2.0 (2.5) | 2.1 (2.4) | 1.7 (2.1) | 2.9 (3.2)* | 2.1 (2.5) |

| Thought Problems | 1.9 (2.6)* | 1.2 (1.9) | 1.5 (2.1) | 1.4 (1.9) | .9 (1.69 | .9 (1.5) | .7 (1.3) | .7 (1.2) | 1.6 (2.3)* | .8 (1.4) |

| Attention Problems | 15.9 (11.8)* | 10.5 (10.7) | 11.8 (10.7) | 12.9 (10.9) | 11.0 (9.6) | 9.9 (9.0) | 8.9 (8.3) | 6.3 (6.8) | 13.3 (11.2)* | 9.3 (8.8) |

| Rule-Breaking Behavior | 2.9 (2.8)* | 1.4 (2.5) | 1.8 (2.4) | 1.7 (2.4) | 1.2 (2.2) | 1.7 (2.4) | 1.2 (1.3) | .9 (1.7) | 2.1 (2.6)* | 1.4 (2.1) |

| Aggressive Behavior | 8.9 (8.5)* | 5.3 (6.9) | 5.5 (6.4) | 5.7 (6.5) | 4.7 (5.5) | 4.1 (5.3) | 3.5 (4.6) | 3.1 (4.1) | 6.5 (7.3)* | 3.9 (5.0) |

| Internalizing | 10.7 (8.9)* | 8.8 (8.4) | 8.9 (7.8) | 12.4 (8.5)* | 8.8 (7.3) | 8.6 (7.0) | 9.6 (7.3) | 9.5 (7.5) | 10.5 (8.5)* | 9.1 (7.3) |

| Externalizing | 11.5 (10.8)* | 6.7 (9.2) | 7.3 (8.3) | 7.4 (8.5) | 6.3 (7.4) | 5.8 (7.4) | 4.7 (5.9) | 4.1 (5.5) | 8.6 (9.5)* | 5.3 (6.7) |

| Total Problems | 45.6 (32.9)* | 30.5 (29.6) | 33.4 (27.4) | 38.9 (28.8)* | 31.1 (24.8) | 28.9 (23.8) | 27.4 (21.3) | 23.7(19.9) | 38.5 (30.3)* | 28.3 (22.9) |

| DSM-oriented | ||||||||||

| Affective Problems | 3.1 (3.2)* | 2.4 (2.7) | 2.6 (2.6) | 3.4 (2.9)* | 2.1 (2.5) | 1.9 (2.3) | 2.0 (2.4) | 1.8 (2.2) | 2.9 (2.9)* | 1.9 (2.4) |

| Anxiety Problems | 1.9 (2.1)* | .9 (1.5) | 1.3 (1.4) | 1.9 (1.8)* | 1.3 (1.6) | 1.1 (1.4) | 1.5 (1.6) | 1.5 (1.7) | 1.6 (1.9)* | 1.3 (1.6) |

| Somatic Problems | .7 (1.5) | .5 (1.4) | .7 (1.5) | .8 (1.4) | .6 (1.4) | .5 (1.2) | .6 (1.4) | .5 (1.1) | .7 (1.5) | .5 (1.3) |

| ADH Problems | 8.1 (6.7)* | 5.2 (5.9) | 5.9 (6.2) | 5.9 (6.1) | 6.4 (5.5) | 5.3 (5.1) | 4.8 (4.4) | 3.4 (3.7) | 6.5 (6.3)* | 5.2 (4.9) |

| Oppositional Defiant problems | 2.1 (2.2)* | 1.5 (2.2) | 1.2 (1.6) | 1.5 (1.8) | 1.1 (1.5) | 1.1 (1.6) | .8 (1.3) | .9 (1.4) | 1.6 (1.9)* | .9 (1.4) |

| Conduct Problems | 4.8 (5.1)* | 2.2 (3.9) | 2.7 (3.9) | 2.2 (3.6) | 2.3 (3.4) | 1.9 (3.2) | 1.2 (2.3) | .8 (1.9) | 3.2 (4.4)* | 1.6 (2.9) |

All means were significant at p<.05.

The 10 TRF items with the highest mean scores for orphanage care sample (range from .63 to .72) included the Attention Problems syndrome with items as follows: 4. Fails to finish things he/she starts; 8. Can’t concentrate, can’t pay attention for long; 10. Can’t sit still, restless or hyperactive; 13. Confused or seems to be in fog; 22. Difficulty following directions; 41. Impulsive or acts without thinking; 61. Poor school work; 73. Behaves irresponsibly; 78. Inattentive or easily distracted; and 92. Underachieving, not working up to potential. The 10 TRF items with the lowest mean scores for orphanage care sample (range from .01 to .21) included: 47. Overconforms to rules; 55. Overweight; 56c. Nausea, feels sick; 56e. Rashes or other skin problems; 56g. Vomiting, throwing up; 70. Sees things that aren’t there; 91. Talks about killing self; and 99; Smokes, chews, sniffs tobacco; 105. Uses alcohol or drugs for nonmedical purposes; and 108. Is afraid of making mistakes.

The 10 TRF items with the highest mean scores in the community sample (range from.56 to .61) included mostly from the Attention Problems syndrome were: 4. Fails to finish things he/she starts; 8. Can’t concentrate, can’t pay attention for long; 22. Difficulty following directions; 41. Impulsive or acts without thinking; 60. Apathetic or unmotivated; 61. Poor school work; 72. Messy work; 73. Behaves irresponsibly; 78. Inattentive or easily distracted; and 92. Underachieving, not working up to potential; and 100. Fails to carry out assigned tasks. The 10 items with the lowest mean scores (range from .01 to .20) included 18. Deliberately harms self or attempts suicide; 40. Hears sounds or voices that aren’t there; 47. Overconforms to rules; 56a. Aches or pains; 56e. Rashes or other skin problems; 56g. Vomiting, throwing up; 70. Sees things that aren’t there; 82. Steals; 85. Strange ideas; and 91. Talks about killing self.

3.2.2. Prevalence of behavioral problems in the orphanage and community care groups

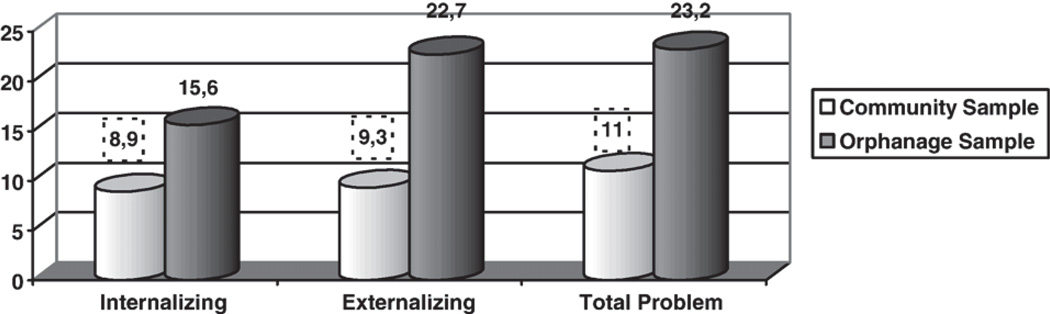

Scale scores may also be used in categorical variables way to describe the prevalence of behavioral problems. The prevalence of Internalizing, Externalizing and Total Problem were also examined. The lower limit of the clinical range was defined by the 90th percentile on all three scales. The clinical ranges varied according to child residence (Total Problem; 11% in our community sample, 23.2% in orphanages; Internalizing 8.9%, 15.6%; Externalizing 9.3%, 22.7% respectively); cross-comparison significantly differed (P<.05), with children rearing in their own families having the lowest rate in all three scales. The Externalizing prevalence is higher than Internalizing in the orphanage and community samples (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of Internalizing, externalizing and total problems children reared in orphanages and families for the TRF.

3.3. Protective and risk factors

3.3.1. Bivariate analyses

In preliminary analyses, influence of background variables was tested for children, parents and schools on Social, Thought Problems, Attention, Internalizing, Externalizing and Total Problems. Table 2 presents the correlations between problem scores and continuous independent variables including the age of child, age at first admission, and competencies of the child. The factors ‘age’ and ‘age at first admission’ showed low negative correlation with the ‘Social, Thought, Attention Problems, Externalizing and Total Problems (P<.05). No significant relationship was found between age, age at first admission and Internalizing (P>.05). The factors ‘academy, working, behaving, and happy’ showed negative correlations with all problem scores. Child ‘good competencies and social support’ had lower emotional and behavioral problems (P<.05).

Table 2.

Correlation between emotional and behavioral problems some continuous independent child variables for the TRF

| Independent variables |

Social Problems |

Thought Problems |

Attention Problems |

Internalizing | Externalizing | Total Problems |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −.197* | −.159* | −.222* | .019 | −.234* | −.183* |

| Age at first admission | −.117* | −.195* | −.223* | −.108 | −.214* | −.210* |

| Perceived social support | −.109* | −.077 | −.159** | −.027 | −.144** | −.121** |

| Competences | ||||||

| Academy | −.364** | −.328** | −.530** | −.238** | −.335** | −.447** |

| Working | −.441** | −.358** | −.633** | −.320** | −.428** | −.552** |

| Behaving | −.431** | −.351** | −.581** | −.117* | −.529** | −.501** |

| Happy | −.369** | −.264** | −.425** | −.361** | −.311** | −.433** |

| Total competence | −.480** | −.381** | −.653** | −.313** | −.487** | −.582** |

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level,

correlation is significant at the 0.05 level.

Gender was significantly related to some problems (P<.05): orphanage boys presented more Attention Problems, Externalizing and Total Problems. Teachers did not rate boys and girls differently on Social, Thought Problems, and Internalizing problems (P<.05). The reason for admission was significantly related to teacher-reported Attention and Total Problems score (P<.05). Children admitted for abuse showed more Attention and Total Problems than those who were admitted to the orphanage care for reasons of family disruption or poverty. There were no significant differences according to the previous residence, and had a sibling in the same orphanage (P>.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mean scores of emotional and behavioral problems according to the according to dichotomous child variables for the TRF

| Independent variables | Social Problems |

Thought Problems |

Attention Problems |

Internalizing | Externalizing | Total Problems |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Boys | 3.3 (3.5) | 1.8 (2.5) | 15.2 (12.4)* | 10.3 (8.8) | 11.1 (11.2)* | 43.3 (33.9)* |

| Girls | 2.7 (3.0) | 1.4 (2.0) | 12.4 (10.9) | 11.8 (8.9) | 7.3 (8.8) | 37.3 (29.7) |

| Reason for admission | ||||||

| Family disruption | 2.9 (3.3) | 1.6 (2.3) | 12.6 (11.8) | 10.7 (9.2) | 8.7 (10.1) | 37.9 (32.5) |

| Poverty | 3.4 (3.7) | 1.3 (2.1) | 15.7 (12.9) | 12.1 (8.4) | 11.7 (12.8) | 46.5 (34.8) |

| Abuse | 4.5 (4.1) | 4.6 (4.2) | 21.3 (12.6)* | 14.5 (13.4) | 16.5 (17.6) | 53.9 (28.7)* |

| Previous residence | ||||||

| Parental home | 3.1 (3.3) | 1.7 (2.4) | 13.9 (11.6) | 11.3 (8.7) | 9.7 (11.1) | 41.4 (32.9) |

| Relatives | 2.6 (4.4) | 1.3 (2.7) | 9.4 (11.5) | 9.8 (10.6) | 6.9 (9.6) | 31.7 (36.7) |

| Another orphanage | 2.9 (3.0) | 1.6 (2.1) | 14.3 (12.99 | 11.4 (9.7) | 9.3 (9.0) | 41.1 (33.1) |

| Moves between orphanages | ||||||

| None | 2.9 (3.8) | 1.5 (2.2) | 10.5 (10.6) | 11.3 (10.4) | 6.5 (9.1) | 34.2 (32.3) |

| More than 2 moves | 2.9 (3.0) | 1.6 (2.2) | 14.7 (11.9)* | 11.1 (8.3) | 9.9 (10.3)* | 41.9 (31.3)* |

| Siblings in the same orphanage | ||||||

| Yes | 2.9 (3.3) | 1.4 (2.2) | 12.9 (11.6) | 11.0 (8.7) | 8.5 (10.5) | 38.4 (31.8) |

| No | 2.7 (3.5) | 1.5 (2.4) | 11.9 (11.7) | 10.0 (9.7) | 9.2 (10.9) | 36.9 (35.5) |

p<.05.

Table 4 indicates that children’s behavior was significantly better when they had parents/relatives, and regular contact with them (P<.05). Parental psychiatric disorder was unrelated to any of the six key measures of the children’s behavior (P>.05).

Table 4.

Mean scores of emotional and behavioral problems according to family/relatives variables

| Independent variables | Social Problems |

Thought Problems |

Attention Problems |

Internalizing | Externalizing | Total Problems |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Situation of parents | ||||||

| Alive | 2.5 (2.9) | 1.3 (1.9) | 11.5 (10.5) | 10.8 (9.4) | 7.1 (8.8) | 34.9 (28.1) |

| Died/unknown | 3.8 (3.7) | 2.0 (2.9) | 15.9 (13.9)* | 11.3 (9.5) | 12.8 (12.5)* | 47.1 (38.6)* |

| Regular contact with parents/relatives | ||||||

| Yes | 2.4 (3.2) | 1.4 (2.3) | 10.8 (11.7) | 9.3 (8.49) | 7.8 (10.0) | 33.1 (31.9) |

| No | 3.9 (3.8)* | 1.8 (2.3)* | 15.7 (12.2)* | 12.5 (10.7)* | 9.7 (10.3)* | 45.6 (34.6)* |

| Parental psychiatric disorder | ||||||

| Yes | 2.9 (3.2) | 1.7 (2.3) | 12.6 (11.0) | 10.5 (8.8) | 9.3 (10.9) | 38.4 (31.9) |

| No | 2.9 (3.3) | 1.6 (2.4) | 13.6 (129) | 9.8 (8.7) | 9.4 (10.4) | 38.8 (33.5) |

p<.05.

As shown in Table 5, the regular relationship between the classroom teacher and orphanage staff statistically decreased the problem behavior scores (P<.05). On the other hand, children involved in approved work had a lower score from all dimensions of problem behaviors. There were statistically significant differences with respect to either characteristics of close friends or stigmatization (P<.05).

Table 5.

Mean scores of emotional and behavioral problems according to school variables for the TRF

| Independent variables | Social Problems |

Thought Problems |

Attention Problems |

Internalizing | Externalizing | Total Problems |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Regular contact between teachers and orphanage staff | ||||||

| Yes | 2.3 (3.0) | 1.2 (2.0) | 10.0 (10.5) | 9.12 (8.7) | 7.4 (9.3) | 31.4 (29.9) |

| No | 4.0 (3.5)* | 1.9 (2.0) | 18.4 (13.9)* | 12.0 (9.1)* | 11.4 (10.9)* | 49.4 (35.0)* |

| Appropriate task involvement | ||||||

| Yes | 1.9 (2.6) | .84 (1.6) | 7.6 (7.7) | 8.67 (8.2) | 5.8 (7.5) | 25.9 (24.4) |

| No | 4.3 (3.7)* | 2.5 (2.8)* | 20.5 (14.1)* | 11.4 (9.4)* | 14.1 (12.6)* | 54.4 (37.5)* |

| Characteristics of close friends | ||||||

| Negative behaviors | 4.0 (3.7)* | 2.1 (2.9)* | 19.3 (14.8)* | 8.8 (9.0) | 15.4 (13.6)* | 51.0 (39.2)* |

| Positive behaviors | 2.3 (2.9) | 1.2 (1.8) | 9.5 (9.7) | 10.0 (8.7) | 6.2 (7.4) | 30.5 (27.7) |

| Stigmatization | ||||||

| Yes | 8.0 (3.6)* | 3.2 (4.0)* | 24.6 (12.8)* | 13.2 (9.4)* | 19.0 (14.0)* | 70.6 (31.5)* |

| No | 2.6 (3.2) | 1.4 (2.2) | 12.0 (12.1) | 9.6 (8.8) | 8.5 (10.3) | 35.6 (32.3) |

p<.05.

3.4. Multivariate analyses

In a multiple regression analyses with forced entry of all variables, those variables that showed significant relations in our previous analyses were examined. Table 6 displays the results of the multiple regression models for the Total Problems. Multiple regression models explained about 73% of the total variance of Total Problems. In this multivariate model, several risk and protective factors surfaced as significant predictors of orphans’ Total Problems. Risk factors that predicted Total Problems at the level (P<.05) were: chronological age; age at first admission; history of admission because of abuse; and stigmatization. The protective factors were also stronger predictors of outcome. Regular contact with parents or relatives, regular contact between classroom teachers and orphanage staff, appropriate task involvement, perceived social support, and competency were all associated with −4.1 to −20.8 point reduction in Total Problems scores. Index child’s gender, if parents were alive or deceased, moves between orphanages and characteristics of close friend did not predict behavior problems significantly (P>.05).

Table 6.

Results of multiple regression model explaining total problems score

| Variables | B | T | P | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −1.573 | −2.374 | 0.018 | (−2.87)–(−.30) |

| Gender (male) | 3.542 | 0.987 | 0.324 | (−3.52)–(10.6) |

| Age at first admission | −.127 | −2.397 | 0.017 | (−.23)–(−.023) |

| Reason for admission (abuse) | 18.001 | 2.266 | 0.024 | (2.37)–(13.36) |

| Moves between orphanages | −6.162 | −1.541 | 0.124 | (−14.03)–(1.71) |

| Died or unknown parents | 5.970 | 1.396 | 0.164 | (−2.45)–(14.32) |

| Regular contact with parents/relatives | −11.370 | −2.478 | 0.014 | (−20.2)–(−2.36) |

| Regular contact between teachers and orphanage staff | −12.87 | −2.385 | 0.018 | (−23.53)–(−2.22) |

| Appropriate task involvement | −20.83 | −4.191 | 0.001 | (−30.6)–(−11.02) |

| Positive characteristics of close friends | −9.628 | −1.731 | 0.085 | (−20.60)–(1.35) |

| Stigmatization | 38.645 | 2.667 | 0.008 | (10.06)–(67.23) |

| Perceived Social support | −14.73 | −3.284 | 0.001 | (−23.54)–(−5.91) |

| Total competencies | −4.109 | −13.673 | 0.001 | (−4.70)–(−3.52) |

R=.780; R2=.726 F=6.642; .001; Durbin–Watson=1.912.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of emotional and behavioral problems among children and adolescents reared in orphanages compared to nationally representative and similarly aged community sample of children brought up within their own families, and to define the characteristics of any protective and risk factors. We found that children and adolescents living in orphanages compared to the community sample exhibited substantially and significantly higher levels of empirically based TRF scales as well DSM-oriented scales with the exception of Anxious/Depressed and Somatic Complaints subscales. Young boys in orphanage care had more emotional/behavioral problems overall than older boys in the orphanage care, as well as boys in the community samples; these findings are similar to that by Vorria and colleagues (1998).

The 10 items with the highest mean scores rated by the teachers included: poor attention; concentration; task persistence; school achievement; shyness, perfectionism; being self-conscious; being afraid to make mistakes; and being overly sensitive to criticism. The 10 items with the lowest scores reflect problems that are more severe and/or less commonly observed in the school setting, such as seeing and hearing things that aren’t there, strange ideas, suicide or self-injury, stealing, substance use, and various somatic problems without known medical cause.

Teachers reported higher prevalence rate for Externalizing (22.7%) than Internalizing problems (15.6%) for children and adolescents reared in orphanage care. The prevalence of behavioral disturbance in the community sample of school-aged children and adolescents has been estimated to be between 7% and 20% (Brandenburg, Friedman, & Silver, 1990) while within the studies involving child welfare samples, the average prevalence rate for externalizing problems was 42%. These numbers suggest that, youth in child welfare settings have over twice the likelihood of having externalizing behavior problems when compared with the community based samples. There is therefore a solid evidence base indicating that externalizing behavioral disorders are extremely widespread among children and adolescents cared for in the child welfare settings. Woodward, Fergusson, and Belsky (2000) found that the earlier the child parental separation, the higher the externalizing behavior problems exhibited by the child, and lower the child’s sense of attachment. Consideration of practical issues such as health care costs and overwhelmed nature of social care systems highlights the need to effectively target those individuals exhibiting disruptive behavior problems (Keil & Price, 2006).

This study investigated protective and risk factors in a representative sample of children reared in orphanages. Protective factors related to family, intellectual capabilities and social support were found to be significantly associated with the problem behaviors. The results were consistent with the results of previous studies that indicated that the risk of psychopathology might be lesser in children remaining in contact with a parent or a parental figure, obtaining social support and improving their competencies in the orphanage (Masten & Coatsworth, 1998; Rutter, 1990; Werner & Smith, 1982). Two other protective factors included: regular contact between school teachers and orphanage staff; and appropriate task involvement. There is now widespread agreement that effective collaboration between orphanage social care staff and school teachers at all levels is central to decreasing problems. For example, through close cooperation between orphanage staff and teachers, difficulties can be identified at an earlier stage so that appropriate additional supports can be provided and the risk of psychopathology reduced (Jackson, 1994).

In this study, several risk factors were identified. One of them was stigmatization. This observation involved negative attitudes towards the children because they lived in orphanage care – from peers at school aswell as others in their social environment – this exerting an important adverse influence for emergence of emotional and behavioral problems. Prior research also shows that stigmatization associated with mental illness adds to the public health burden of mental illness. Stigmatization leads to loss of social status and ensuing discrimination triggered by negative stereotypes about people labeled as abnormal (Link & Phelan, 2001). Such stigma impedes recovery by eroding the individual’s social status, social networks, and self-esteem thus contributing to poor outcomes such as increased isolation, feelings of hopelessness and psychological symptoms (Ritsher, Otilingam, & Grajales, 2003; Rosen, Walter, Casey, & Hocking, 2000). It is inevitably very important for all social services staff to acknowledge that stigmatization and its associated prejudice, is not only a rights violation, but form a real risk factor for the development of children and adolescents in orphanage care.

A possibility that children admitted for financial convenience and/or family disruption factors may have had less adverse experiences during their period of early family care was further examined. Thus, if their early family relationships were good it might be expected that these youngsters would be more likely to maintain positive family ties during their period in institutions. In this study it was seen that emotional abuse and neglect had substantial negative effect on emergence of emotional and behavioral problems in affected children. This finding is consistent with previous research clearly documenting that maltreatment during childhood leads to higher incidence of physical, emotional, behavioral as well as cognitive problems (Cicchetti & Toth, 2000; De Bellis, 2001; Manly, Kim, Rogosch, & Cicchetti, 2001). Abuse and neglect of children may take many forms, from a lack of care for their physical needs, through a failure to provide consistent love and nurturance, to overt hostility and rejection (New & Skuse, 1999). It is likely that children and adolescents in orphanage care were exposed to full range of such early experiences as well.

As expected, the duration of institutional care was correlated with problem behaviors; the children who had spent longer period of time in institutional care exhibited higher severity of problem behaviors. This finding is also consistent with prior studies (Ames, 1997; Beckett et al., 2002; Fisher, Ames, Chisholm, & Savoie, 1997; Marcovitch et al., 1997).

Previous research has highlighted that having a parent with mental disorder and associated psychosocial adversity and parenting problems frequently precede a child’s admission to orphanage care (Quinton & Rutter, 1988). Nevertheless, our findings support Vorria et al.’s (1998) observations that parental psychiatric disorder was unrelated to any of the behavioral problems in children in this study. This may reflect the psychosocial adversity and parenting problems among these families that lead to institutionalization in Turkey, irrespective of any identifiable parental mental disorder.

4.1. Implications for early intervention, social policy and professionals in the field

The results of this study has immediate practical implications for improvement of the assessment and intervention conditions for children who have experienced a range of deprivation experiences and who continue to be care for in orphanages across the country. The identification of risk and protective factors regarding the emotional and behavioral health of children in orphanage care can directly assist social workers, psychologists and other staff in identifying essential interventions and setting priorities. The children and adolescents in orphanage care are at risk for developing a variety of emotional and behavioral problems—i.e., it’s not necessarily the conditions that precede their placement, but the very nature of care within institutions, that contribute to poor mental health outcomes. For this reason, in order to eliminate the stigma and discrimination these children face, there is a need for more intensive, multi-faceted interventions, preferably including parents or relatives and other caregivers including classroom teachers. We recommend that these involve addition of parent management training programs including enhanced and regular contact with their families, relatives and classroom teachers, social skills training and problem solving skills training programs for the children and adolescents, and increased supports for improving their competencies. This study has identified the importance of including parents, caregivers and classroom teachers in the prevention of children’s mental health problems. The development of such methods will increase the efficacy of parents or relatives as team members in the orphanage care settings as well as the implementation of required early interventions. Nonetheless, the child welfare and social workers face multiple barriers as they attempt to include parents, teachers, and trusted caregivers as members of the child care teams. In the absence of policies that eliminate institutional care of children altogether, new policies and legislative changes need to promote innovative collaborations between these caregivers that might include shared building and recreation space, appropriate shared activities such as parent–child support and school–orphanage support groups, among other activities.

The child welfare system, and policy makers as well as mental health practitioners ought also to ensure safe and stable social care environments for children and adolescents. In order to create ‘high-quality safe environments and child-friendly care models’ for children in orphanage care, at the policy level, child welfare systems must scrutinize potential carers, organize training program and evaluate care systems, maintain high standards of staff conduct, provide them with support and with necessary advocates in order to strengthen children’s rights, and promote their wellbeing. A successful evidence based prevention program will require developmentally sensitive child welfare policies and practices designed to promote the healthy development of children and adolescents in orphanage care. This entails availability of ongoing screening programs for early diagnosis and treatment, assessment of children’ needs, and coordinated systems of physical and psychosocial care.

Families today in developing countries are struggling to cope with rapid and startling social change. Poverty, economic and social crisis, immigration, and mental illness have all contributed to children being placed in institutional care due to abandonment, child abuse or neglect. The full impact of this situation has not yet be fully assessed but nevertheless vast number of children are already suffering worldwide from this care system. Therefore urgent effort is needed in order to develop early intervention programs for preventing the separation of children from their families in the first place by developing support services for families in need, counseling services to prevent abandonment and rehabilitation services for parents who are at risk of abusing/neglecting their children. Finding ways for child welfare professionals to collaborate more closely and successfully with early intervention programs in early childhood, mental health, rehabilitation would greatly increase viable opportunities for children and families involved in the system. Finally, alternative care models need to be promoted such as foster care or adoption systems and family based homes in the community.

5. Limitations

This study provides a first but necessary step in understanding how different pattern of history, child, family and school variables are differentially associated with diverse mental health outcomes in children in orphanage care. However, additional research is needed to replicate these findings and to investigate the potential underlying mechanisms that explain the differential association of emotional and behavioral problems and predictive variables.

The results of this study should be viewed in the light of a number of limitations. The study was predominantly based on teacher reports. It is clear that assessment of emotional and behavioral problems would be most effective if it includes multi-informant assessments. The gathering of ratings by caregivers and by children is thus currently underway.

Another limitation, because of the study cross-sectional nature of this study, it is difficult for us to draw conclusions about any causal relationship between orphanage rearing and mental health problems. Nevertheless, such an approach provides useful information in testing future hypothesis. Therefore, despite the limitations of the cross-sectional design of this study, our national sampling frame in both the orphanage and community samples generated empirical knowledge to describe the mental health of children and adolescents for representative groups of institutional and family reared children in the community. This research is also unique in that it contributes to very limited published research on mental health of children and adolescents in orphanage care in developing countries.

6. Conclusion

Overall, the findings in this study suggest that children in orphanages are at high risk for a range of adverse emotional and behavioral outcomes. As the multivariate analyses also showed, increased loading of protective factors reduces the presence of emotional and behavioral problems, thus hopefully leading to a more positive long-term prognosis. All those involved in the care of children – whether professionals, parents or other members of the community – have important responsibilities for promoting their rights; we should also be ready to voice them whenever needed. Although we are a long way away from fulfilling these rights, each step taken is likely to better lead to reducing adverse developmental circumstances faced by these vulnerable children.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Social Services and Child Protection General Directorate’ staff for their help and support for the implementation of this study. We would like to express our gratitude to all the teachers who gave up time for interviews and completing the forms. Funding for this project was provided by the Fogarty/NIH ICOHRTA grant D43 TWO5807 (K.M.).

Footnotes

The authors undersigned warrants that the material contained in the manuscript represents original work, has not been published elsewhere, and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Contributor Information

Zeynep Simsek, Email: zsimsek@harran.edu.tr.

Nese Erol, Email: erol@medicine.ankara.edu.tr.

Kerim Münir, Email: kerim.munir@childrens.harvard.edu.

References

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock C. Manual for the teachers report form and teacher version of the child behavior profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ames EW. Development of Romanian Orphanage children adopted to Canada. Ottowa, Canada: Final report to the Human Resources Development Office; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Beckett C, Bredenkamp D, Castle J, Groothues C, O’connor TG, Rutter M, et al. Behavior problems associated with institutional deprivation: A study of children adopted from Romania. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2002;23:297–303. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200210000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berube RL, Achenbach TM. Bibliography of published studies using ASEBA instruments: 2004 edition. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Brandenburg NA, Friedman RM, Silver S. The epidemiology of childhood psychiatric disorders: Prevalence findings from recent studies. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1990;29:76–83. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199001000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth S. Developmental processes in maltreated children. In: Hansen D, editor. Nebraska symposium on motivation: Motivation & child maltreatment, Vol 46, 1998. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press; 2000. pp. 85–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Convention on the Rights of Child, U.N. General Assembly. Document A/RES/44/25. (12 December 1989 with annex). [Google Scholar]

- De Bellis M. Developmental Traumatology: The psychobiological development of maltreated children and its implications for research, treatment, and policy. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:539–564. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401003078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Groot A, Koot HM, Verhulst FC. Cross-cultural generalizability of the youth self-report and teacher’s report form cross-informant syndromes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1996;24(5):651–664. doi: 10.1007/BF01670105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumenci L, Erol N, Achenbach TM, Simsek Z. Measurement structure of the Turkish translation of the Child Behavior Checklist using confirmatory factor analytic approaches to validation of syndromal constructs. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32(3):337–342. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000026146.67290.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eker D, Arkar H. Çok boyutlu algılanan sosyal destek ölçeğinin faktör yapısı, geçerlik ve güvenirliği. Türk Psikoloji Dergisi. 1995;34:45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BH, Fisher PA, Zaharie S. Predictors of disruptive behavior, developmental delays, anxiety, and affective symptomatology among institutionally reared Romanian children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(10):1283–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000136562.24085.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erol N, Simsek Z. Mental health of Turkish children: Behavioral and emotional problems reported by parents, teachers, and adolescents. In: Singh NN, Leung JP, Singh AN, editors. International perspectives on child and adolescent mental health. Proceedings of the first international conference, Vol 1. Oxford, UK: Elsevier; 2000. pp. 223–246. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher L, Ames EW, Chisholm K, Savoie L. Problems reported by parents of Romanian orphans adopted to British Columbia. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1997;20:67–83. [Google Scholar]

- Garmezy N. Stress-resistant children: The search of protective factors. In: Stevenson JE, editor. Recent research in developmental psychopathology. Tarrytown, NY: Pergamon Press; 1985. pp. 213–233. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garmezy N, Masten A. The protective role of competence indicators in children at risk. In: Cummings EM, editor. Lifespan developmental psychology: Perspectives on stress and coping. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1991. pp. 151–176. [Google Scholar]

- General Directorate of Social Services, National Activity Plan, (shcek@gov.tr) [Date of access: 08.08.2005];

- Goldfarb W. The effects of early institutional care on adolescent personality. Journal of Experimental Education. 1943;12:106–129. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson S. Education on residential child care. Oxford Review of Education. 1994;20(3):267–279. [Google Scholar]

- Kazarian SS, McCabe SB. Dimensions of social support in the MSPSS: Factorial structure, reliability and theoretical implications. Journal of Community Psychology. 1991;19:150–160. [Google Scholar]

- Keil V, Price JM. Externalizing behavior disorders in child welfare settings: Definition, prevalence, and implications for assessment and treatments. Children and Youth Services Review. 2006;28:761–779. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:363–385. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar S. Vulnerability and resilience. A study of high risk adolescents. Child Development. 1991;62:600–616. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01555.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar S, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development. 2000;71(3):543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maclean K. The impact of institutionalizing on child development. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:853–884. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly J, Kim J, Rogosch F, Cicchetti D. Dimensions of child maltreatment and children’s adjustment: Contributions of developmental timing and subtype. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:759–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten A. Resilience in development: Implications of the study of successful adaptation for developmental psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, editor. The emergence of a discipline: Rochester symposium on developmental psychopathology. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1987. pp. 261–294. [Google Scholar]

- Masten A, Coatsworth JD. Competence, resilience and psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology: Risk, disorder and adaptation, Vol 2. Newyork: JohnWiley and Sons, Inc; 1995. pp. 715–752. [Google Scholar]

- Masten A, Coatsworth JD. The developmental of competence in favorable and unfavorable environments: Lessons from research on successful children. American Psychologist. 1998;53(2):205–220. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann JB, James A, Wilson S, Dunn G. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in young people in the care system. British Medical Journal. 1996;313:1529–1530. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7071.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcovitch S, Goldberg S, Gold A, Washington J, Wasson C, Krekevich K, et al. Determinants of behavioral problems in Romanian children adopted to Ontario. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1997;20:17–31. [Google Scholar]

- New M, Skuse D. Child maltreatment. In: Steinhausen HC, Verhulst FC, editors. Risks and outcomes in developmental psychopathology. Oxford University Press; 1999. pp. 314–328. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini DS. Psychosocial risk and protective factors in childhood. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1990;11(4):201–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinton D, Rutter M. Parenting breakdown: The making and breaking of intergenerational links. Aldershot, U.K.: Aveburg; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Randazzo KVD, Landsverk J, Ganger W. Three informants’ reports of child behavior; parents, teachers, and foster parents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42(11):1343–1349. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000085753.71002.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritsher JB, Otilingam PG, Grajales M. Internalized stigma of mental illness: Psychometric properties of a new measure. Psychiatry Research. 2003;121:31–49. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen A, Walter G, Casey D, Hocking B. Combating psychiatric stigma: An overview of contemporary initiatives. Australian Psychiatry. 2000;8:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Rushton A, Minnis H. Residential and foster family care. In: Rutter M, Taylor E, editors. Child and adolescent psychiatry. Blackwell Publishing; 2002. pp. 359–372. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1987;57(3):316–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1987.tb03541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. In: Rolf J, Masten JS, Cicchetti D, Nuechterlein KH, Weintraub S, editors. Risk and protective factors in the developmental of psychopathology. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp. 651–682. [Google Scholar]

- Roy P, Rutter M, Pickles A. Institutional care: Risk from family background or pattern of rearing? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2000;41(2):139–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitz R. The psychogenic diseases in infancy. Psychoanal Study Child. 1951;6:255–275. [Google Scholar]

- The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team. Characteristics of children, caregivers, and orphanages for young children in St. Petersburg, Russian Federation. Applied Developmental Psychology. 2005;26:477–506. [Google Scholar]

- Tizard B, Hodges J. The effect of early institutional rearing on the development of eight-year-old children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1978;19:99–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1978.tb00453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorria P, Wolkind S, Rutter M, Pickles A, Hobsbaum A. A comparative study of Greek children in longterm residential group care and in two-parent families: II. Possible mediating mechanisms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1998;39(2):237–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner E, Smith R. Vulnerable but invincible: A longitudinal study of resilient children and youth. New York: Adams, Bannister, and Cox; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff PH, Fesseha G. The orphans of Eritrea: Are orphanages part of the problem or part of the solution? American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:1319–1324. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.10.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward L, Fergusson D, Belsky J. Timing of parental separation and attachment to parents in adolescence. Results of a prospective study from birth to age 16. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62(1):162–173. [Google Scholar]

- Zimet GD, Dahlen NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assesment. 1988;52:30–41. [Google Scholar]