Abstract

Objective

Depression is the most common adult outcome of exposure to childhood sexual abuse (CSA). In this study, we retrospectively assessed the length of time from initial abuse exposure to onset of a major depressive episode.

Method

A community-based survey of childhood experiences in 564 young adults (ages 18 to 22 years) conducted between 1997 and 2001 identified 29 right-handed female subjects with CSA but no other exposure to trauma. Subjects were interviewed for lifetime history and age of onset of Axis I disorders using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders.

Results

Sixty-two percent (n = 18) of the sexual abuse sample met full lifetime criteria for major depression. Episodes of depression emerged, on average, 9.2 ± 3.6 years after onset of exposure to sexual abuse. Mean survival time from onset of abuse to onset of depression for the entire sample was 11.47 years (95% CI: 9.80 – 13.13 years). There was a surge in new cases between 12-15 years of age. Average time to onset of posttraumatic stress disorder was 8.0 ± 3.9 years.

Conclusions

Exposure to CSA appears to sensitize women to the development of depression, and to shift age of onset to early adolescence. Findings from this formative study suggest that clinicians should not interpret the absence of symptoms at the time of CSA as a sign of resilience. Continued monitoring of victims of CSA as they pass through puberty is recommended. Reasons for the time lag between CSA and depression are proposed along with potential strategies for early intervention.

INTRODUCTION

Childhood exposure to trauma in general, and sexual abuse in particular, has been linked to a host of adverse consequences. Recent epidemiological studies suggest that exposure to trauma and household dysfunction account for about 50% of the population attributable risk for major depression and suicide.1, 2 Specific associations between exposure to childhood sexual abuse (CSA) and subsequent development of depressive disorders have been observed in large samples of adults3-5 as well as in adolescents6, 7. Depression is the most extensively documented outcome of exposure to CSA in adults8, but in children the most discernible manifestations are sexualized behaviors rather than depression or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).8

Despite the numerous studies demonstrating an association between exposure to CSA and emergence of depression, we are not aware of any studies that have specifically reported on the length of time between exposure to CSA and development of major depression. There are several possibilities. One is that depression follows rapidly on the heels of exposure to CSA. Another possibility is that depression emerges after exposure or risk of exposure to CSA has abated.

A third possibility is that CSA does not directly lead to depression, but that it sensitizes the individual, enhancing their risk of developing depression as they pass through adolescents into middle-age as part of a neuromaturational process.9 Major depression can emerge at any age, but the greatest surge in newly emergent cases occurs between 15-18 years in females.10 Recent studies indicate that the average age of onset for major depression is 32 years. Females outnumber males 2:111 with gender differences in prevalence emerging between 11-15 years of age.12 Hence, depression may emerge with an unusually high frequency in CSA exposed individuals during the 15–18 year adolescent surge, or later in adulthood, as part of the natural course of the disorder. A fourth possibility is that CSA could both sensitize and accelerate the process leading to an earlier age of onset, as has been reported to occur in patients with bipolar13 or substance abuse disorders.14 Finally, episodes of major depression may emerge in sensitized individuals only if they are exposed to new losses or traumas, resulting in a very variable onset time between individuals.

Determining the temporal relationship between CSA and onset of depression is difficult, as CSA usually occurs in individuals who have been, or will be, exposed to multiple other forms of trauma.15, 16 However, delineating the time course is a fundamental prerequisite for designing intervention strategies to prevent or minimize the long-term sequelae of abuse and for interrupting the cycle of violence.

To begin to address this issue we retrospectively examined the temporal relationship between CSA and depression in a group of subjects participating in our ongoing studies of trauma16 who were exposed to CSA but to no other forms of trauma or severe early stress. We now report that there was an average lag of 9.2 years between the onset of CSA and onset of depression, and that most of the subjects exposed to early abuse who developed major depression had their first depressive episode occur between 12–15 years of age.

METHOD

Detailed ratings of symptoms and exposure to emotional abuse and trauma were collected and analyzed from 564 young adults 18-22 years of age (mean 19.8 ± 1.4 yr; 385F/179M) who responded to community advertisements requesting either healthy normal controls or individuals with history of unhappy childhood as part of a larger study of childhood abuse.16 Because a primary goal of the larger study was to examine the relationship between trauma and brain development17, subjects were also required to be right handed, unmedicated, and free of any significant history of fetal, neonatal, or childhood disorders that could adversely affect brain development. The study was approved by the McLean Hospital IRB. All subjects gave written informed consent prior to completion of questionnaires and again prior to interview and assessment.

History of exposure to CSA was obtained in a two-step process. The first step was self-report, followed by detailed assessment using the semi-structured Traumatic Antecedents Interview (TAI).18 Individuals with CSA were initially identified if they responded in the affirmative to the question: “Have you ever been forced into doing more sexually than you wanted to do or were too young to understand? (By “sexually” we mean being forced against your will into contact with the sexual part of your body of his/her body).” They were also asked to provide information on their relationship to this individual, number of times they were forced, age of first and last abuse, and whether or not they felt terrified or had their life or another persons life threatened.16

Respondents reporting CSA were further evaluated using the TAI, which is a 100-item semi-structured interview designed to elicit and evaluate reports of physical abuse, sexual abuse, witnessing violence, physical neglect, emotional neglect, significant separations, losses, verbal abuse, and parental discord.18 The reliability of TAI variables range from acceptable to excellent (median intraclass R = .73).18

For this formative study, we selected only respondents who indicated, on both self-report and TAI interview, that they experienced three or more episodes of forced contact CSA accompanied by fear or terror. Further, they had not experienced any other types of childhood abuse or other severe stressors (e.g., gang violence, motor vehicle accidents, near drowning, natural disasters, animal attacks). We required a history of three or more exposures based on the assumption that CSA is typically a repeated event, and that a major factor affecting brain development may be persistent fear of recurrence. Using these criteria, 29 female and 3 male respondents were identified for study. Results are limited to females due to known gender differences in prevalence rates for depression and small size of our male sample.

Psychiatric history was assessed by certified mental health clinicians (clinical nurse specialists or Ph.D. psychologists) using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID), the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Dissociative Disorders (SCID-D)19 and the Diagnostic Interview for Borderline Patients (DIB).20 Age of onset was assessed as a part of this interview, which can be reliably determined through this form of assessment.21, 22

Kaplan-Meier analysis (SPSS version 11.0) provided mean survival time (±95% confidence interval [CI]) for onset of CSA, and from onset of CSA to emergence of depression. Additional analyses were conducted to examine time between exposure to CSA and onset of PTSD as it became clear that a substantial number of subjects met criteria for this diagnosis.

The resulting sample consisted of 29 females with a mean (±SD) age of 20 ± 1.3 years. All were in college, and 90% came from a middle class or higher socioeconomic status family (SES 2.3 ± 1.0). Reported perpetrators were part of the extended family and/or members of the community, with only three perpetrators being step-parents. None of the subjects in this sample reported experiencing CSA by their biological parents.

RESULTS

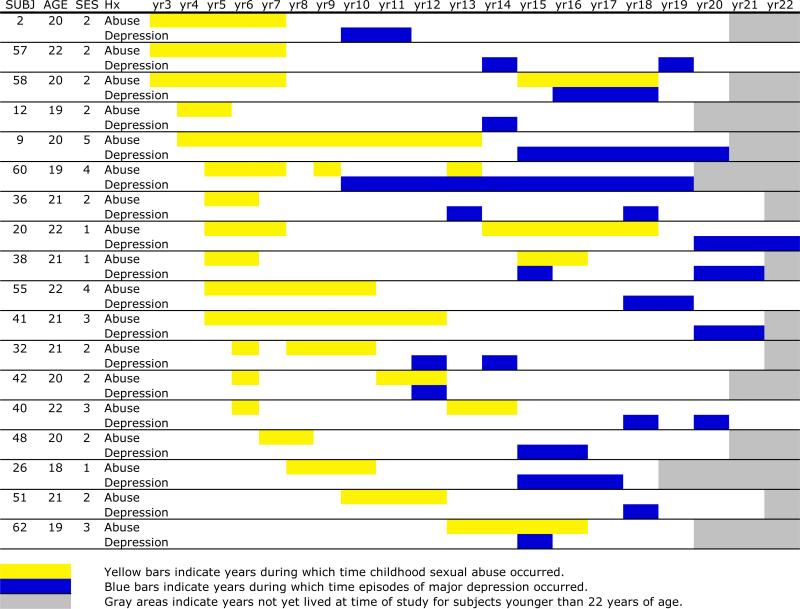

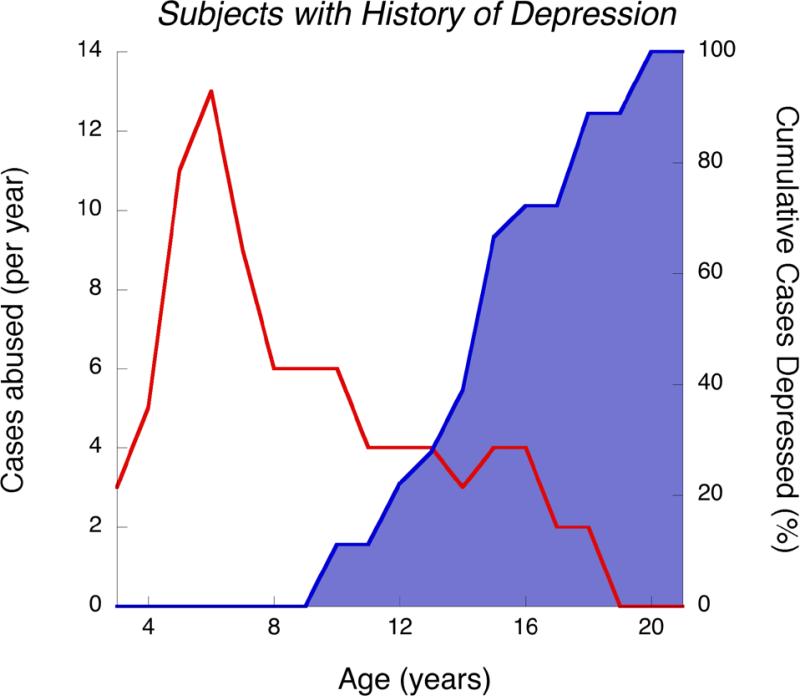

As illustrated in Figure 1, subjects who developed major depression (n=18) had onset of CSA between 3–13 years of age (mean survival to CSA = 6 years; 95% CI: 5–7 years), and onset of depression between 10–20 years of age (mean survival 15.0 years; 95% CI: 13.6–16.4 years). Eighty-three percent (n = 15) of these subjects experienced significant suicidal ideation during their index episode of major depression. The average time from onset of CSA to onset of major depression, in those who developed depression, was 9.2 ± 3.6 years. Mean survival time from onset of CSA to onset of depression for the entire sample was 11.47 years (95% CI: 9.80–13.13 years). Mean survival from offset of CSA (first episode if there were multiple perpetrators) was 9.55 years (95% CI: 7.45–11.65 years). Figure 2 illustrates the number of cases with a history of depression who experienced CSA in a given year, and the cumulative prevalence of depression. Note that many of the subjects who went on to develop major depression experienced CSA at ages 5 and 6, and that 56% of depressive episodes began between 12–15 years of age.

Figure 1.

Relationship between age of experience of childhood sexual abuse and onset of depression.

Figure 2.

Age of abuse and cumulative incidence of depression for 18 CSA subjects developing depression. Red line and left axis indicate number of subjects exposed to CSA at each age. Blue shaded area and right axis indicate the percentage of subjects who had an episode of major depression prior to or during each year of age.

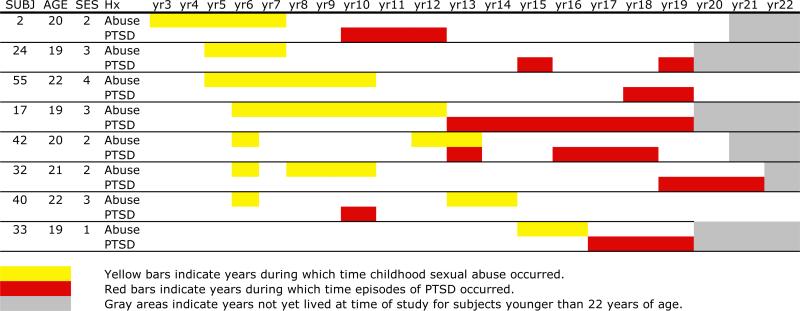

Subjects who met criteria for PTSD (n=8) had onset of abuse between 3–15 years of age (mean survival 7 years; 95% CI: 4–9 years) and onset of PTSD between 10–19 years of age (mean 14 years; 95% CI: 12–17 years) (Figure 3). The average survival time from onset of abuse to onset of PTSD was 8 years (95% CI: 5–11 years). Five of these subjects had a comorbid history of major depression. In three cases, depression and PTSD developed within a year of each other. In one case, PSD preceded depression by 8 years and in the other depression preceded PTSD by 7 years.

Figure 3.

Relationship between age of experience of childhood sexual abuse and onset of PTSD.

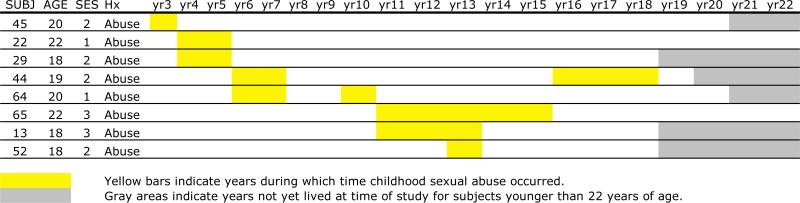

Eight CSA-exposed subjects (27.5%) have not so far met diagnostic criteria for major depression or PTSD. These subjects experienced abuse between 3–13 years of age (mean survival 7 years; 95% CI: 5–10 years) (Figure 4). On average, 12.3 ± 4.4 years (range 5–17) have elapsed between onset of CSA and age at the time of diagnostic assessment. Average duration of abuse exposure in this group was 2.9 ± 2.0 years. Subjects who developed PTSD or depression had a mean duration of abuse exposure of 4.7 ± 2.5 years (F = 3.23, df = 1,27 p = 0.08). Eighteen percent of subjects who have not developed depression (2/11) had parents with a definite history of depression versus 11% (2/18) of the sample who developed depression (Fisher exact, p > 0.6).

Figure 4.

Age of experience of childhood sexual abuse in subjects without history of depression or PTSD.

Of interest, seven of the subjects who developed depression subsequent to exposure to childhood sexual abuse reported a second (or third) sequence of abuse occurring either before or after the onset of depression. We examined this “multiple exposure” subgroup to determine if the time to onset of depression was related to number of sequences of abuse. On average, there was a 4.1±2.3 year gap between sequences, and depression emerged 2.6±2.4 years after the start of the second sequence. However, while depressions tended to occur soon after the second exposure to abuse, there was no statistically significant difference between this group and those with a single abuse sequence in time to onset of depression following onset or offset of the first sequence of abuse. On average, depression emerged 9.1±3.5 years after initial exposure in subjects with a single sequence of CSA, and 9.4±4.2 years in subjects with multiple sequences (F = 0.04, df = 1,16 p > 0.8). Two of eight subjects developing PTSD, and 2/8 subjects with neither PTSD nor depression, reported multiple sequences. Hence, within this limited sample there was no evidence to suggest that multiple exposure sequences increased the likelihood or hastened the onset of depression or PTSD.

In addition to depression and PTSD, three subjects had lifetime diagnoses of dissociative disorders, two had obsessive compulsive disorder, two had separation anxiety disorder, two had substantial cannabis use, one had generalized anxiety disorder, one had bulimia nervosa, and one had an adjustment disorder. None met criteria for borderline personality disorder.

DISCUSSION

A full 62% (n=18) of our sample of young adult women with history of exposure to CSA met diagnostic criteria for major depression, and 45% (n=13) of the sample met criteria by age 16. The expected prevalence rate for any depressive disorder in females by age 16 is 11.7%,23 and life-time prevalence rate for major depression in women in the population at large is about 20%.12 The elevated rate reported by these CSA subjects is remarkable for many reasons. First, this was a non-clinical sample selected without regard to psychopathology. Second, the entry criteria excluded subjects currently receiving medications or with a history of drug or alcohol abuse. Third, subjects were exposed to only one form of trauma, which is relatively rare (33% of CSA subjects in the original sample), and finally, at the time of the study, they were younger than the mean age of onset expected for major depression.

One possibility is that our advertisements seeking individuals with histories of abuse or unhappy childhood could bias recruitment to include a preponderance of individuals with depression. Of interest, eight of the 29 subjects reported in this paper answered the advertisement for normal controls. There were no significant differences between CSA subjects responding to the advertisement targeting normal controls or targeting individuals with unhappy childhood in rates of present or past depression or PTSD, no significant differences in ages of onset or offset of abuse, and no significant differences in the time lag between age of abuse and onset of Axis I pathology. The high rate of occurrence of major depression in this sample is consonant with the epidemiological finding of Kendler et al5 that CSA involving intercourse was associated with a 3.14-fold increase in lifetime prevalence of major depression. We did not require CSA subjects to experience intercourse, but required at least three episodes of forced sexual contact accompanied by fear or terror, which probably also ensured that the experience was highly traumatic.

The high rate of occurrence of depression in young adult women with a history of CSA was not however, the major point of the study. High prevalence rates for major depression have been reported in large epidemiological samples of older adults with CSA.3-5 The key finding of this formative study is that episodes of major depression or PTSD did not immediately occur following exposure to CSA, but took several years to emerge. Further, the onset of depression did not directly coincide with the abatement of CSA. Rather, there was typically a long delay between exposure to CSA and onset of depression, with a surge in new cases occurring between 12–15 years of age. This is somewhat earlier than the peak surge of newly emergent cases reported to occur, between 15–18 years of age, in a prospective longitudinal study of a contemporary birth cohort.10 Overall, these findings are most compatible with the hypothesis that CSA sensitizes the individual to later emergence of depression during adolescence, and that it shifts the peak period of risk from mid-adolescence to early adolescence. This finding is consistent with a previous report of earlier age of onset of depression in women with histories of childhood abuse.24

Clinically, this is important information as it shows that there may be substantial time available in which to potentially intervene to minimize the most common major psychiatric consequences of CSA. Moreover, these findings warn against the fallacy of assuming a child who experienced CSA is out of danger, if she did not develop depression or PTSD during, or within months, of her period of exposure. Finally, these findings also suggest a need for extra vigilance when working with children with a history of CSA as they pass through puberty into early adolescence.

These are important caveats as some therapists maintain that it is inappropriate to treat children for sexual abuse per se, and that treatment needs to be directed toward specific presenting conditions.25 They argue that half of all cases of CSA appear asymptomatic26, and in such cases of extra-familial abuse, treatment can be short-term and problem-focused, assisting parents to provide the psychological and social support their child needs.25 This perspective may be shortsighted. What we recognize as common disorders in adult medicine and psychiatry may be the result of what we failed to recognize or treat in childhood.15

This sample of young adult subjects exposed to repeated bouts of CSA had had high lifetime prevalence rates for major depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, yet none met criteria for borderline personality disorder. This may seem surprising as CSA is frequently considered a major risk factor for developing borderline personality disorder.27 There are several possible reasons why we failed to find an association. First, age of onset for borderline personality disorder is typically between 19 and 34 years of age, so our subjects were just entering the age of risk. Second, they were in college, which can provide a significant degree of external structure and opportunity for less demanding relationships. Third, research by Heffernan and Cloitre28 suggests that the development of borderline personality disorder in women exposed to CSA is associated with co-occurrence of maternal physical or verbal abuse. We excluded individuals from the study who had these, or any other, multiple abusive experiences. Fourth, none of the subjects in this study indicated that the perpetrator was a biological parent, and only three subjects reported abuse by a step-parent. The predominantly extra-familial nature of the abuse may have spared these individuals from some of the more pathological psychosocial consequences of CSA16.

Given the high risk for major depression that appears to be associated with CSA, might there be effective intervention strategies that can provide prophylaxis? Answers to this question will likely to depend on: (1) the mechanisms mediating or moderating this risk; and, (2) the constellation of factors responsible for the emergence of depression in adolescence or adulthood in sensitized individuals.

The first consideration are the potential ways that exposure to early stress can exert a sensitizing affect on brain development or later behavior. Theoretically, this can occur through epigenetic modifications29, 30 that program stress response systems31, and through establishment of set-points for neurotransmitter function or neurotrophic factors32.

Of particular relevance is the finding by Caspi et al33 on the role of the serotonin transporter in moderating the influence of stressful life events on susceptibility to major depression. Briefly, they found in a prospective-longitudinal study that the short-allele functional polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene linked promoter region (5-HTTLPR), associated with reduced transcriptional efficiency, markedly increased risk for developing depression in individuals exposed to childhood maltreatment. However, this polymorphism did not increase risk for developing depression in the absence of early stress. Since the serotonin transporter is largely responsible for inactivation of released serotonin, one interpretation of this finding is that risk for depression stems from over activation of the serotonin system during development. This may seem counterintuitive given the role of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in the treatment of depression. However, this hypothesis fits with preclinical observation that certain enduring effects of early experience are mediated through transient alterations in serotonin release34, and that exposure to drugs that enhance serotonin neurotransmission during early life result in depressive symptoms during adulthood35, 36.

If over activation of serotonin neurotransmission during development is a moderating or mediating factor responsible for sensitization, then certain therapeutic hypotheses follow. First, drugs that diminish firing rate of serotonin neurons, such as the anxiolytic drug buspirone37, may have prophylactic properties if administered acutely. Second, SSRIs administered early may paradoxically increase risk, particularly in individuals with the protective polymorphism associated with higher transcriptional efficiency of the serotonin transporter.

Delayed onset of symptoms may have some relationship to the overproduction and pruning of dendrites, axons, synapses and receptors that occurs during postnatal development. We have previously reported that exposure to early stress in rats is associated with a significant reduction in hippocampal synaptic density. This reduction occurs as a consequence of diminished synaptic overproduction, and is not apparent until after puberty.38 This may help to explain why five studies reported reduced hippocampal volume in adults with histories of childhood physical or sexual abuse39-43, whereas three studies failed to find hippocampal volume reduction in abused children.44-46

Volumetric MRI scans were obtained on 26 (90%) of the subjects included in this study, and have been published elsewhere17. Briefly, we found evidence for reduced hippocampal volume bilaterally in these young adult women, particularly in those who experienced CSA between 3-5 or 11-13 years of age. Corpus callosal area was reduced in individuals with CSA between 9-10 years of age, and frontal cortex gray matter volume was reduced in individuals with CSA between 14-16 years of age.17 It may be the case that CSA during early sensitive periods exerts delayed affects on the hippocampus, which become manifest after puberty along with symptoms of major depression.

The delay in symptom onset provides a window of opportunity for treatment32, and preclinical studies suggest a variety of strategies that may be beneficial. First, exposure to early stress can exert enduring deleterious effects on brain and behavior of rodents by producing an epigenetic modification (methylation) of the glucocorticoid receptor promoter site regulating the expression of receptors for corticosteroids, such as cortisol. However, environmental experiences such as increased maternal care can reverse (i.e., unmethylate) the epigenetic modification by inducing an early response gene (NGFI-A, also known as erg-1 and zif286).30 Hence, it is conceivable that certain forms of psychosocial contact (e.g. nurturing contacts) may reverse epigenetic programming of the glucocorticoid systems to overreact. This may then prevent or curtail the deleterious effects of stress hormones on the hippocampus.47 Kaufman et al48 found that the presence of positive social supports helped to protect children with the short-allele of 5-HTTLPR from developing depression following exposure to childhood abuse.

Second, hippocampal neurogenesis and synaptogenesis are persistently reduced by exposure to early stress, and may consequently lead to the development of depression.49 Vigorous exercise, environmental enrichment, or exposure to certain types of cognitive tasks50-52 may stimulate these processes, and thus, may constitute possible routes for preventive interventions geared toward preserving hippocampal neurogenesis. Whether these findings can be extrapolated to humans is an open question, but they provide a theoretical rationale for developing novel intervention strategies to protect against a major adverse consequence of exposure to CSA. Pereira et al53 recently reported the possibility of tracking changing in neurogenesis/angiogenesis in the human hippocampus using imaging techniques.

To our knowledge this is the first study to analyze the time delay between exposure to CSA and emergence of major depression, and to indicate the importance of this temporal relationship for development of rational intervention strategies. This study is limited by use of retrospective assessment methods, the small sample size and by the uniqueness of the participants, who were exposed to CSA but to no other form of childhood traumatic stress. This however was an important prerequisite for the analysis, and a large sample of subjects were carefully screened to recruit this special population. Moreover, given that our population was not selected from a clinical setting, and that respondents to our community solicitations were primarily college students, we expect that our subjects represent the higher functioning group of individuals exposed to CSA, and perhaps represent individuals who might be labeled as “resilient” in other studies. Rates of psychopathology may have been even greater if our sample included subjects who reported multiple forms of abuse throughout childhood.16 However, if we are correct about adolescence being a critical age for the emergence of depression, then these individuals would have shown a similar onset pattern.

It is likely that other investigators have data sets that can be analyzed in a similar manner to support or refute these findings. Understanding the maturational events that intervene between CSA and adverse outcomes such as depression, PTSD or substance abuse may provide the necessary insights to establish an integrative science of preventive psychiatry.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by RO1 grants to MHT from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH-53636) and National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA-017846), along with donor support from NARSAD and the John W. Alden Trust.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No authors have a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chapman DP, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. J Affect Disord. 2004;82:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, et al. Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. Jama. 2001;286:3089–3096. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.24.3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wise LA, Zierler S, Krieger N, Harlow BL. Adult onset of major depressive disorder in relation to early life violent victimisation: a case-control study. Lancet. 2001;358:881–887. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06072-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fergusson DM, Swain-Campbell NR, Horwood LJ. Does sexual violence contribute to elevated rates of anxiety and depression in females? Psychol Med. 2002;32:991–996. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702005986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kendler KS, Bulik CM, Silberg J, et al. Childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric and substance use disorders in women: an epidemiological and cotwin control analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:953–959. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.10.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donald M, Dower J. Risk and protective factors for depressive symptomatology among a community sample of adolescents and young adults. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2002;26:555–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2002.tb00366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kilpatrick DG, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R, et al. Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbidity: results from the National Survey of Adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:692–700. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Putnam FW. Ten-year research update review: child sexual abuse. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:269–278. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andersen SL, Teicher MH. Stress, sensitive periods, and maturational events in adolescent depression. Trends in Neuroscience. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.01.004. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, et al. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107:128–140. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessler RC. Epidemiology of women and depression. J Affect Disord. 2003;74:5–13. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Post RM, Leverich GS, Xing G, Weiss RB. Developmental vulnerabilities to the onset and course of bipolar disorder. Dev Psychopathol. 2001;13:581–598. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401003091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, et al. Childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: the adverse childhood experiences study. Pediatrics. 2003;111:564–572. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.3.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14:245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teicher MH, Samson JA, Polcari A, McGreenery CE. Sticks, stones, and hurtful words: relative effects of various forms of childhood maltreatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:993–1000. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andersen SL, Tomada A, Vincow ES, et al. Preliminary evidence for sensitive periods in the effect of childhood sexual abuse on regional brain development. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2008 doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.20.3.292. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roy CA, Perry JC. Instruments for the assessment of childhood trauma in adults. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192:343–351. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000126701.23121.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bremner JD, Steinberg M, Southwick SM, et al. Use of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Dissociative Disorders for systematic assessment of dissociative symptoms in posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:1011–1014. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.7.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gunderson JG, Kolb JE, Austin V. The diagnostic interview for borderline patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1981;138:896–903. doi: 10.1176/ajp.138.7.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farrer LA, Florio LP, Bruce ML, et al. Reliability of self-reported age at onset of major depression. J Psychiatr Res. 1989;23:35–47. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(89)90015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prusoff BA, Merikangas KR, Weissman MM. Lifetime prevalence and age of onset of psychiatric disorders: recall 4 years later. J Psychiatr Res. 1988;22:107–117. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(88)90075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, et al. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gladstone GL, Parker GB, Mitchell PB, et al. Implications of childhood trauma for depressed women: an analysis of pathways from childhood sexual abuse to deliberate self-harm and revictimization. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1417–1425. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolf TL, Campbell TW. Effective treatments for children in cases of extra-familial sexual abuse. Issues in Child Abuse Accusations. 1994;6:207–213. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caffaro-Rouget A, Lang RA, vanSanten V. The impact of child sexual abuse. Annals of Sex Research. 1989;2:29–47. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herman JL, Perry JC, van der Kolk BA. Childhood trauma in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146:490–495. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.4.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heffernan K, Cloitre M. A comparison of posttraumatic stress disorder with and without borderline personality disorder among women with a history of childhood sexual abuse: etiological and clinical characteristics. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2000;188:589–595. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200009000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meaney MJ, Szyf M. Environmental programming of stress responses through DNA methylation: life at the interface between a dynamic environment and a fixed genome. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2005;7:103–123. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2005.7.2/mmeaney. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weaver IC, D'Alessio AC, Brown SE, et al. The transcription factor nerve growth factor-inducible protein a mediates epigenetic programming: altering epigenetic marks by immediate-early genes. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1756–1768. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4164-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu D, Diorio J, Tannenbaum B, et al. Maternal care, hippocampal glucocorticoid receptors, and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to stress. Science. 1997;277:1659–1662. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5332.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andersen SL. Trajectories of brain development: point of vulnerability or window of opportunity? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27:3–18. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, et al. Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science. 2003;301:386–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1083968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smythe JW, Rowe WB, Meaney MJ. Neonatal handling alters serotonin (5-HT) turnover and 5-HT2 receptor binding in selected brain regions: relationship to the handling effect on glucocorticoid receptor expression. Developmental Brain Research. 1994;80:183–189. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(94)90103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vogel G, Neill D, Hagler M, Kors D. A new animal model of endogenous depression: a summary of present findings. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1990;14:85–91. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andersen SL, Dumont NL, Teicher MH. Differences in behavior and monoamine laterality following neonatal clomipramine treatment. Dev Psychobiol. 2002;41:50–57. doi: 10.1002/dev.10055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jann MW. Buspirone: an update on a unique anxiolytic agent. Pharmacotherapy. 1988;8:100–116. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-9114.1988.tb03543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Andersen SL, Teicher MH. Delayed effects of early stress on hippocampal development. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1988–1993. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bremner JD, Randall P, Vermetten E, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging-based measurement of hippocampal volume in posttraumatic stress disorder related to childhood physical and sexual abuse--a preliminary report. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;41:23–32. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(96)00162-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stein MB. Hippocampal volume in women victimized by childhood sexual abuse. Psychol Med. 1997;27:951–959. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Driessen M, Herrmann J, Stahl K, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging volumes of the hippocampus and the amygdala in women with borderline personality disorder and early traumatization. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:1115–1122. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.12.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vythilingam M, Heim C, Newport J, et al. Childhood trauma associated with smaller hippocampal volume in women with major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:2072–2080. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.12.2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vermetten E, Schmahl C, Lindner S, et al. Hippocampal and amygdalar volumes in dissociative identity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:630–636. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.4.630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carrion VG, Weems CF, Eliez S, et al. Attenuation of frontal asymmetry in pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50:943–951. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Bellis MD, Keshavan MS, Clark DB, et al. Developmental traumatology. Part II: Brain development. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:1271–1284. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.De Bellis MD, Keshavan MS, Shifflett H, et al. Brain structures in pediatric maltreatment-related posttraumatic stress disorder: a sociodemographically matched study. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:1066–1078. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01459-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McEwen BS. Effects of adverse experiences for brain structure and function. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:721–731. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00964-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaufman J, Yang BZ, Douglas-Palumberi H, et al. Social supports and serotonin transporter gene moderate depression in maltreated children. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17316–17321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404376101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Malberg JE, Eisch AJ, Nestler EJ, Duman RS. Chronic antidepressant treatment increases neurogenesis in adult rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2000;20:9104–9110. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09104.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cotman CW, Berchtold NC. Exercise: a behavioral intervention to enhance brain health and plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:295–301. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bredy TW, Zhang TY, Grant RJ, et al. Peripubertal environmental enrichment reverses the effects of maternal care on hippocampal development and glutamate receptor subunit expression. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:1355–1362. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scaccianoce S, Del Bianco P, Caricasole A, et al. Relationship between learning, stress and hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Neuroscience. 2003;121:825–828. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00514-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pereira AC, Huddleston DE, Brickman AM, et al. An in vivo correlate of exercise-induced neurogenesis in the adult dentate gyrus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5638–5643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611721104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]