Abstract

A tunable 900 MHz transmit/receive volume coil was constructed for 1H MR imaging of biological samples in a 21.1 T vertical bore magnet. To accommodate a diverse range of specimen and RF loads at such a high frequency, a sliding-ring adaptation of a low-pass birdcage was implemented through simultaneous alteration of distributed capacitance. To make efficient use of the constrained space inside the vertical bore, a modular probe design was implemented with a bottom-adjustable tuning and matching apparatus. The sliding ring coil displays good homogeneity and sufficient tuning range for different samples of various dimensions representing large span of RF loads. High resolution in vivo and ex vivo images of large rats (up to 350 g), mice and human postmortem tissues were obtained to demonstrate coil functionality and to provide examples of potential applications at 21.1 T.

Keywords: High magnetic field, MRI, RF coil design, birdcage coil, vertical bore MRI, sliding-ring, 900 MHz, 21.1 Tesla, B1 homogeneity, MRI of rats, in vivo MRI

Introduction

The availability of the high field vertical bore magnets, culminating in the currently highest field of 21.1 T [1], creates opportunities for high resolution in vivo MRI of small animals with increased sensitivity and contrast [2]. So-called “widebore” vertical magnets with a typical bore of 89 mm are relatively cost effective and are widely used for high field solid state NMR applications such as magic angle spinning spectroscopy. However, coils for MRI of small animals have by and large been developed for lower fields and for horizontal bore magnets. High field vertical probes have been reported that are capable of in vivo MRI in rats using surface coils at 11.7 and 17.6 T [3, 4] and phased-array surface coils at 17.6 T [5, 6]. “Millipede” volume coils [7, 8] and conventional birdcages are available commercially for certain microimaging applications for both horizontal and vertical bore magnets. In this report, we describe a 21.1 T vertical bore probe using a single volume coil for both excitation and signal reception, which has sufficient tuning range to accommodate a wide variety of animals and other biological specimens. The volume coil allows a larger and more homogeneous field-of-view (FOV) than can typically be accomplished with surface coils. To access most laboratory rodent models, it is necessary to accommodate adult animals at least as large as mature rats (~350 g). Within a gradient coil designed for an 89 mm bore magnet, there is very limited space remaining around the subject for tuning rods, cables, physiological sensors and animal maintenance apparatus (temperature control, anesthesia, etc.). All necessary cables and tuning rods have been located around the perimeter of the probe to allow the animal to be placed in a head-up configuration and still permit impedance matching from outside the magnet. Furthermore, for a uniquely long vertical system such as the NHMFL 21.1 T magnet, it is valuable to have a modular user probe in which the RF coil is detachable from the more static framework of the mechanical tuning apparatus and animal support system. This allows multiple RF coil inserts to be developed to meet the needs of a wide group of users and potential biomedical applications at moderate cost and fabrication effort.

The birdcage coil is a well-known and understood design [9–13] that provides good transmit/receive field profiles for a volume coil application such as described above. It has good sensitivity and can be readily adapted to quadrature operation; it has excellent radial homogeneity over the large field of view that makes good use of limited bore space. However, tuning the birdcage coil to compensate for a wide range of loads without changing the B1 field pattern and without reducing the sensitivity is a longstanding problem. In small animal coils at lower Larmor frequencies, the resonant capacitance normally can be adjusted at one or two positions along the sinusoidally distributed current in the birdcage legs utilizing the convenience of a variable capacitor. However, at higher operating frequencies and over a diverse range of samples, such adjustment adversely impacts B1 homogeneity. Although dedicated birdcages can be tailored for each specific sample load, this approach is often untenable given the shear diversity of in vivo and ex vivo specimens. Rather, it is desirable to have a compact tuning mechanism that can compensate for a large enough range of frequency shifts without sacrificing the B1 homogeneity or sensitivity.

In this paper, the construction of a general purpose 900 MHz transceiver volume coil is described for imaging applications over a range of samples, such as the in vivo neuroanatomy of rats, multiple ex vivo preserved specimen and postmortem human tissues. The volume coil is a low-pass birdcage [9] that achieves frequency tuning by mechanically varying the geometric overlap between a sliding circular tuner ring and the legs of the birdcage. The tuning ring is adjusted by a mechanical gear that is accessible while the probe is positioned within the magnet bore, allowing for in situ impedance matching. This configuration shares similar features with previously reported designs that used mechanically adjustable coil elements [14–18, 8] or adjustable shield [19]; it is designed to maximize animal space and provide mechanically robust and symmetric remote tuning mechanism within the limited confines of a vertical bore magnet.

This general purpose volume coil has a 33 mm sample aperture accommodating the heads of living rats up to 350 g, the largest body size that fits inside a 57-mm diameter commercial gradient for standard 89 mm widebore vertical systems. Excellent RF homogeneity of this coil was observed at 21.1 T over a diverse range of sample loading conditions. Several high field applications are presented, including high resolution in vivo and ex vivo images of rodents and pathological human tissue.

Methods and Materials

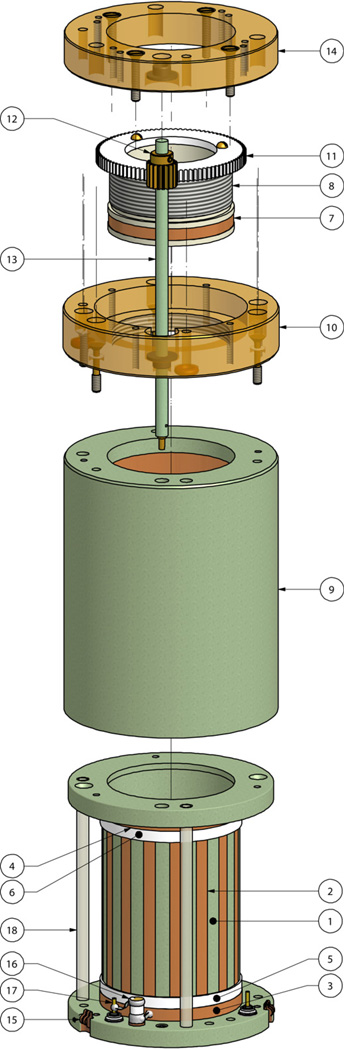

Fig. 1 shows the expanded view of the volume coil assembly with the sliding tuner ring. Hereafter, numbers in brackets correspond to the part number in this drawing. The coil was constructed on a cylindrical former (#1), with 35.6 mm outer diameter and 33.0 mm inner diameter in order to accommodate the head of a 350 g rat. For the prototype, this cylindrical former was machined out of a rod of polyether ether-ketone (PEEK), and the leg pattern (#2) was constructed with self-adhesive copper strips (3.3 mm wide×54.5 mm long) taped to the former’s outer diameter. In the final user version of the coil shown in Fig. 2, the former was machined from a glass-epoxy laminate tube (G-10 grade), and the conductive leg pattern was printed on a flexible copper-clad Kapton polyimide film (Pyralux® FR9110R, DuPont Electronic Technologies, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA), which was wrapped around the former and secured in place by Eccobond 24 adhesive (Emerson & Cuming, Germantown, WI, USA). Sixteen parallel leg strips were distributed evenly around the cylinder. The resulting copper strips had a thickness of 35 µm, which was much greater than two RF skin depths (δs = 2.2 µm) for copper at 900 MHz. The legs were terminated by several layers of 0.8 mm thick Teflon dielectric wrapped around the former (shown in white as #5 and #6, Taega Technologies, High Point, NC, USA). Two 3.3 mm wide copper strips were wrapped on top of these Teflon layers to form static end rings (#3 and #4). The assembly described above comprised the basic resonant structure of the birdcage.

Figure 1.

Coil assembly, exploded view. Legends: 1: G-10 coil former; 2: conductive legs pattern; 3 and 4: bottom and top static end rings; 5 and 6: Teflon layers; 7: sliding copper tuner ring; 8: threaded tuner tube; 9: Faraday shield cover; 10: gearbox flange; 11: large spur gear; 12: pinion gear; 13: tuning shaft with screwdriver jack; 14: gearbox cover; 15: one of three BeCu grounding fingers; 16: match trimmer; 17: MCX RF connectors; 18: tubes for anesthesia gas and vacuum.

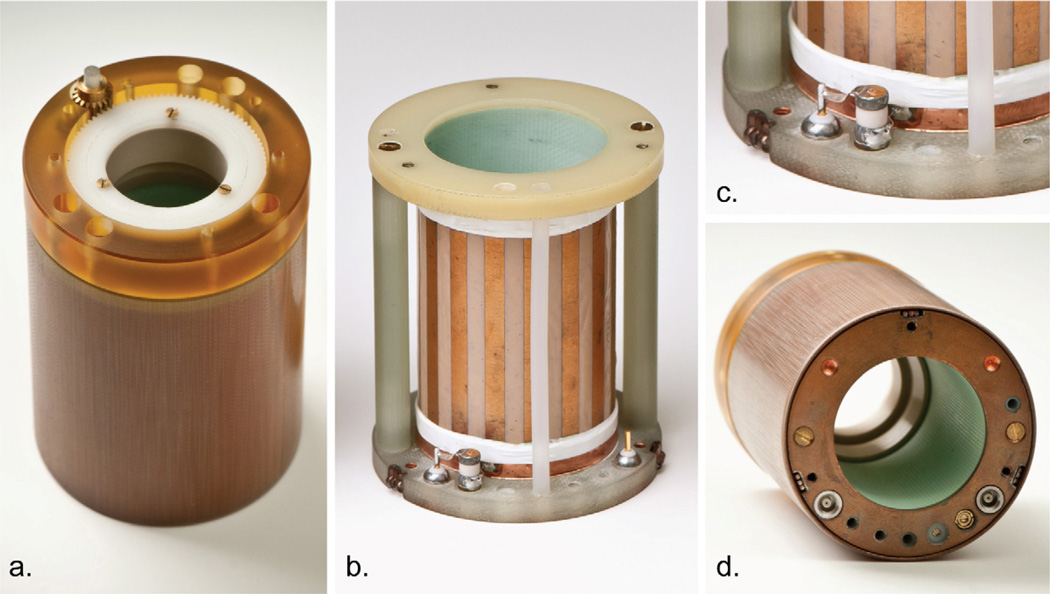

Figure 2.

Photographs of RF coil: (a) top gearbox view; (b) inside the coil; (c) inset showing matching trimmer capacitor and feed point; (d) ports and tuning rods interface of the detachable coil.

To provide adjustable tuning, another 3.3 mm wide copper ring (#7) was mounted on a thin piece of plastic tubing (#8) fitted into the coil former from above. Gradual adjustment of the tuner ring’s vertical position was accomplished by rotating the tube against the threads of a flange (#10) fixed above the coil’s Faraday shield cover (#9). The threaded tube was driven by a large rotating spur gear (#11), which engaged a smaller pinion gear (#12) driven by a tuning shaft (#13). The tuning shaft, in turn, was engaged by another rod passing through the animal cradle. The tuning rod extended to the bottom of the probe body and was accessible from below the magnet. By moving the tuner ring along the coil’s longitudinal axis, the capacitive overlap between the ring and the top edge of each leg varied at a rate of ~0.1 pF/mm (~0.33 pF when fully engaged). The tuning ring had a traveling distance of 3.3 mm, across which a tuning range of 50 MHz was achieved. The number of Teflon layers (#5 and #6) was varied empirically during the construction stage to shift the tuning range so that all samples of interest could be tuned to 900 MHz. To balance the average capacitance at the top end ring due to the sliding tuner ring, the number of Teflon layers in the bottom static ring was kept smaller than in the top ring. The top static end ring also insured that the coil’s FOV remained stable when the sliding ring was adjusted. Because most samples are inserted from the bottom of the coil, the sliding ring located at the very top of the coil introduced little perturbation to the B1 field homogeneity.

The Faraday shield cover was machined from G-10 stock with an ID of 52.9 mm. A very thin layer of 12 µm copper was electroplated onto the inner surface of the entire cover, including vertical and horizontal surfaces. Copper also was plated on the bottom surface of the coil former (Fig. 2d) to complete the Faraday shield and provide a metallized ground plane for mounting connectors and capacitors. The cover and ground plane were shorted electrically by means of three beryllium-copper fingers (#15). Fig. 1 also shows the particular method used to excite the coil. In this design, the variable matching capacitor (#16) (NMA1T4, 0.4–4 pF, Voltronics Corp., Salisbury, MD, USA) had one lead connected to the center pin of a MCX input connector (#17), and the other lead connected to the bottom end ring of the coil (#3). The MCX connector shield was grounded to the Faraday shield that enclosed the coil. Once the drive cable shield was grounded to the coil shield as described above, the 1H resonance became stable and did not change when either the animal body or human hand touched the drive cables. This eliminated the need to employ a cable or balun trap to cancel common mode RF currents, which are induced on the outside of coaxial drive cables [20–22]. In this balunless drive scheme, there was no direct path (e.g. a balancing capacitor) between the birdcage and the outer jacket of drive cable–the return path for the signal was created purely by the electromagnetic coupling between the birdcage legs and Faraday shield [23, 24].

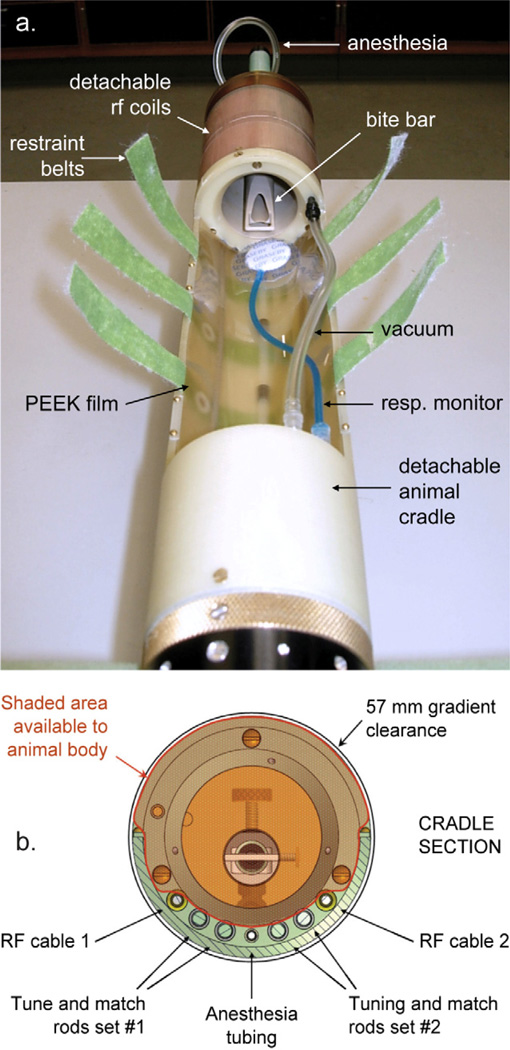

Fig. 3a shows the modular assembly of the coil, the animal cradle and the probe body [25]. The plug-in design of this modular assembly allows coils targeted for specific applications to be interchanged on a single, mechanically stable platform for animal maintenance and restraint. The animal cradle can be disconnected from the probe body and exchanged to accommodate either cleaning or different animal body types. Fig. 3b shows the cross-sectional view of the animal cradle. The rodent body occupies the majority of space in the cradle, while all RF cables, tuning rods, restraint belts and anesthesia tubing are routed under the animal. The position of the rodent’s head is fixed by a bite bar from the top and by Velcro restraints around the body. A thin, 0.5 mm sheet of flexible but tough PEEK plastic is secured underneath the animal so that RF cables and tuning rods are separated from the animal without occupying extra space. A fairly large rat (~350 g) was able to fit into this arrangement and then into a standard 57 mm vertical Mini0.75 microimaging gradient set (Bruker BioSpin Corp, Billerica, MA, USA). A second set of tuning rods and an extra RF cable passing through the cradle were included to allow the use of heteronuclear and quadrature coils, which we will describe elsewhere.

Figure 3.

(a) A picture of the coil assembly mounted on top of an animal cradle. (b) Schematic view of the animal cradle cross-section.

To evaluate the coil performance under different sample loading conditions, two phantoms of vastly different dielectric properties were prepared. The first, a mineral oil sample, represented a very light load. A second phantom was prepared to approximate the RF load and loss expected for the head of an adult rat (300–350 g). This load contained 61% (w/v) polyethylene glycol (PEG) in D2O and 40 mM NaCl. With only a single peak from its methylene protons, the signal from PEG dissolved in D2O has no chemical shift artifact. The ratio of D2O and PEG was used to adjust the dielectric constant, and was tuned to produce the resonance shift observed for a rat head. The concentration of NaCl was adjusted to match the quality factor observed with the rat head. Both phantoms were contained in a 26 mm ID cylindrical tube spanning the length of the coil. Using a network analyzer (8753ES, Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA), the coil Q values were measured as the ratio of 900 MHz resonance frequency to the bandwidth at −7 dB with respect to the S11 curve baseline. Matching trimmer capacitor values were determined via an LCR meter, by measuring the capacitance of an identical trimmer with the same piston displacement.

Performed on the 900 MHz ultra-widebore vertical magnet at the NHMFL, MRI experiments included fast spin-echo (FSE) and gradient recalled echo (GRE) scans acquired using a Bruker BioSpin Avance III spectrometer and either a 0.75 T/m, 57 mm ID Mini0.75 microimaging gradient or, later, a specially built 0.6 T/m, 64 mm ID gradient (Resonance Research Inc., Billerica, MA, USA). To demonstrate feasibility over a range of samples, high resolution 2D and 3D images (as indicated in accompanying figure legends) were acquired from biological specimens (both ex vivo and in vivo) as well as from the aforementioned mineral oil and PEG solutions. In addition to multi-slice FSE scans, multi-slice 2D GRE scans of the mineral oil and PEG samples were conducted to indirectly assess B1+ homogeneity using a double angle method [26–28] for the calculation of 3D tip angle maps. Briefly, two GRE datasets were acquired, one with a prescribed flip angle of α1 = 60° and magnitude image intensity I1 as well as a dataset with a α2 =120° flip angle and intensity I2. With sufficiently long repetition times (TR) and short echo times (TE) such that relaxation could be ignored, the tip angle map as a function of position r was calculated from the relationship:

| (1) |

For in vivo imaging, a Sprague-Dawley rat (Harlan Laboratories, Tampa, FL) was anesthetized with a mixture of 2% isoflurane/98% O2 and monitored using a respiratory pillow interfaced with an animal monitoring and gating system (Model 1025, Small Animal Instruments, Inc., Stony Brook, NY). Images were acquired with a multi-slice 2D FSE sequence (TE/TR = 26/6000 ms) in an axial orientation at a 100×100 µm2 in-plane resolution within 12 minutes. Ex vivo high resolution images of multiple mouse brains and human tissue were acquired with 3D GRE sequences using the Ernst angle after fixation of the specimens with 4% paraformaldehyde, washing with 0.9% phosphate buffered saline and immersion in a susceptibility matching fluorocarbon (FC-43, 3M Corp., St. Paul, MN, USA) to minimize distortion of the B0 field [29–32]. To increase throughput, three ex vivo adult mouse brains (C57BL/6J, Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were imaged simultaneously; each was immersed in FC-43 and placed within individual 10 mm NMR tubes (Wilmad-LabGlass, Vineland, NJ, USA) grouped in the center of the sliding ring birdcage coil. 3D GRE datasets were acquired in 5.5 hr with TE/TR = 7.5/150 ms at an isotropic resolution of 78 µm. For human pathological imaging, a hippocampal section of an Alzheimer’s brain was imaged within a standard plastic cassette used for histological processing. The cassette was centered in a cylindrical container using acrylic positioners. The cylinder was filled with FC-43 to immerse the cassette and brain section. The cylinder was sealed and placed in the center of the sliding ring birdcage. 3D GRE datasets of the hippocampus were acquired to visualize structural alteration resulting from disease at two resolutions: 100 µm isotropic resolution in 7.5 min (TE/TR = 10/25 ms) and 50 µm isotropic in 1 hr (TE/TR = 7.5/50 ms).

Results

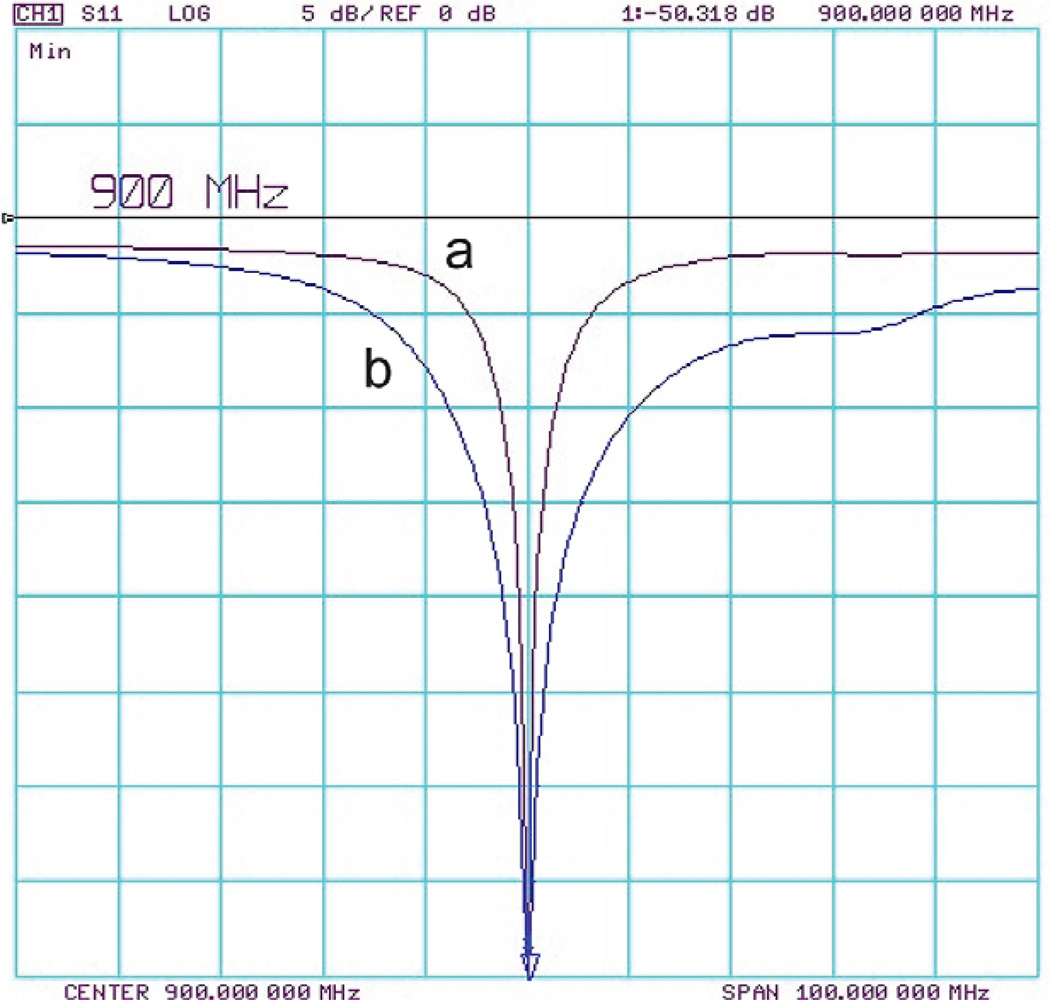

When lightly loaded with mineral oil, the sliding tuner ring was adjusted close to the position of maximum engagement with the legs. The coil Q measured 281, and the matching trimmer was set at ~1.0 pF. When loaded by the PEG phantom, the resonance frequency decreased by 34 MHz from the mineral oil resonance, and the sliding ring was adjusted to have approximately 2.1 mm overlap with the legs so that the resonance frequency of the coil was brought back to 900 MHz. With the animal-matched PEG phantom, the coil Q decreased to 49, (Q measurement accounted for slight S11 interaction with the next resonance mode), and the matching capacitance increased to ~3.0 pF. The range of movement of the sliding ring was sufficient to tune the coil for samples that fell within these two extreme loading conditions, and a series matching trimmer capacitor was used to adjust the coil impedance to 50 Ω. Fig. 4 shows S11 reflection curves of the impedance matched probe under different loading conditions.

Figure 4.

S11 reflection curves of the tuned and matched probe with a) no sample and b) PEG phantom.

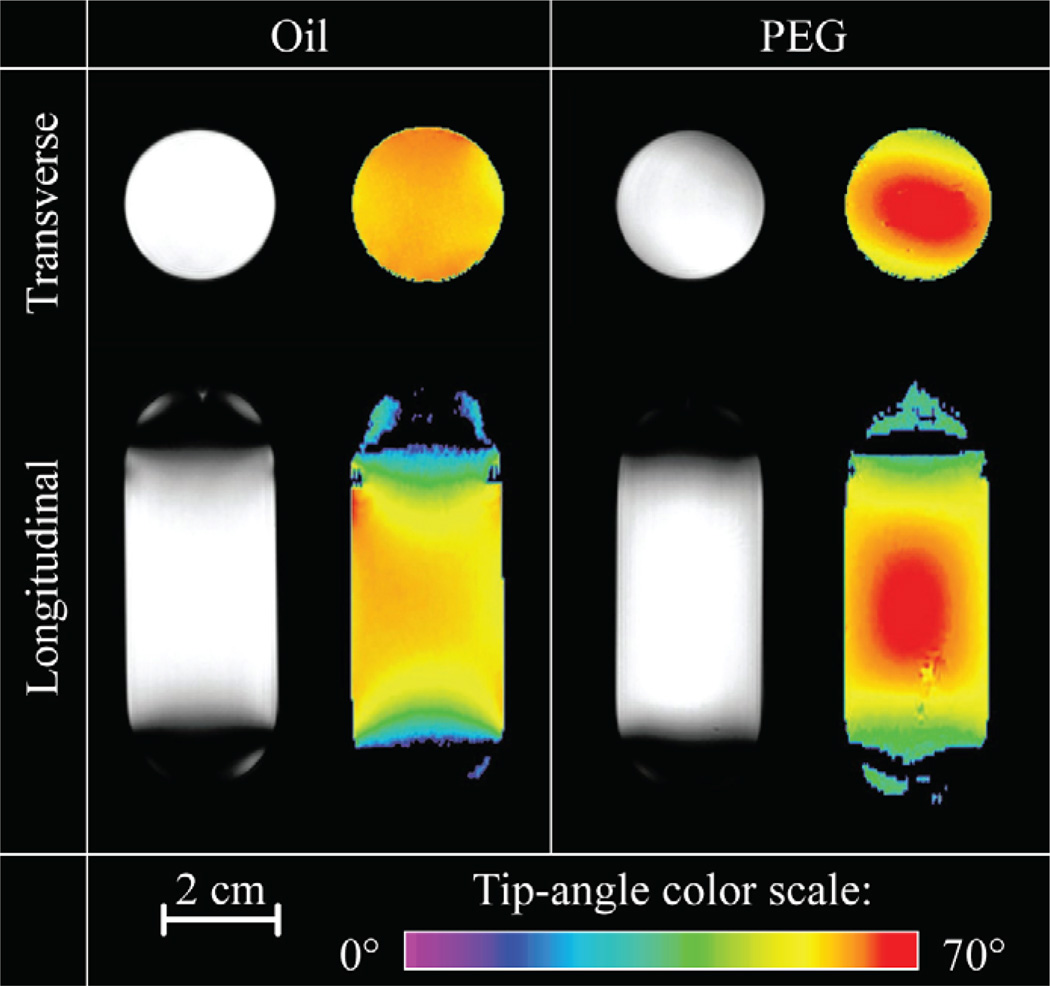

Fig. 5 shows the FSE images and tip angle maps obtained from uniform cylindrical samples (mineral oil and PEG) in transverse and longitudinal planes that pass through coil center. FSE images are shown in grayscale, while tip angle maps generated through the application of equation 1 are displayed in a color scale for the prescribed flip angle of α = 60°, with higher tip angles represented by the higher intensity color. In the longitudinal direction, the coil had an effective FOV of ~54 mm. In the transverse plane, the coil had excellent homogeneity for both phantoms, and there was very little perturbation around the feed point. One can notice the more intense B1 field at the center when the coil is loaded by PEG. This spatial dependent intensity pattern is due to the standing wave interference effect [33–35] at 900 MHz especially in uniform samples with higher dielectric constant.

Figure 5.

Evaluation of the B1+ homogeneity under two different loading conditions. For each phantom, the multi-slice FSE images (left, grayscale) and tip angle maps (right, color) were obtained in transverse and longitudinal directions (shown in same scale). The parameters for the FSE images are: TR= 2 s, effective TE=14.8 ms, NEX= 2, RARE factor = 4, FOV= 4 × 4 cm2 (transverse) and 8 × 4 cm2 (longitudinal). Both the longitudinal and transverse images have an in-plane resolution of 0.3 × 0.3 mm2 and a slice thickness of 1 mm. For the GRE experiments, TR = 5 s, TE = 3 ms, NEX = 1, with the same resolution and FOV as in FSE scans.

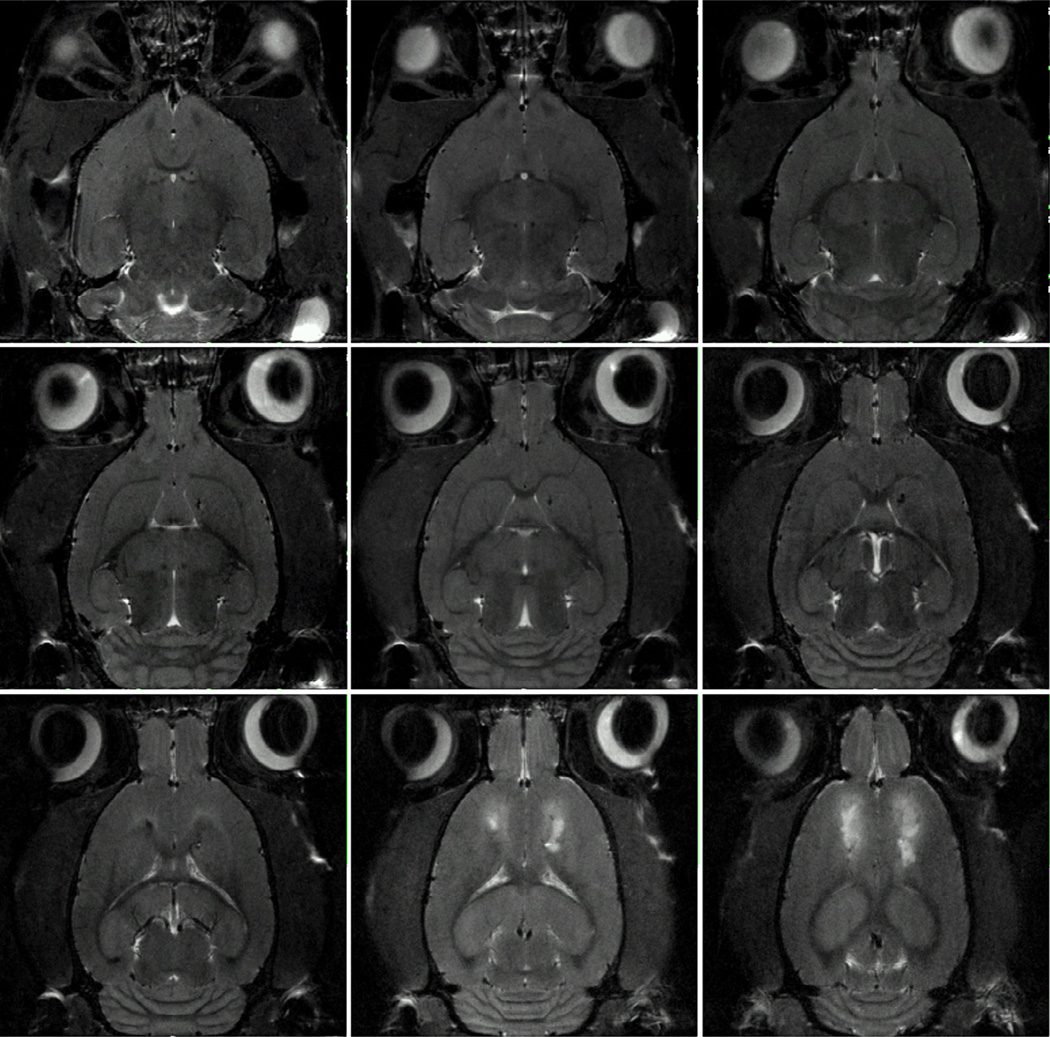

To demonstrate practical applications of the 21.1 T sliding ring imaging coil, several high resolution images were obtained for a range of samples. Fig. 6 is an array of in vivo axial images in a multi-slice FSE dataset of a large anesthetized Sprague-Dawley rat (350g) that had received a permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion to induce an ischemic stroke (hyperintensity evident in the upper cortical region). An aggregate of super-paramagentic iron oxide nanoparticles was injected into the middle cerebral artery without reperfusion; this arterial injection induced a bilateral lesion that was only mitigated by lateral repurfusion. The animal was imaged 24 hrs after the injection. With data acquisition gated to respiration to reduce the effect of motion, these images of the living rat demonstrate both the wide FOV of the sliding ring design as well as its high B1 homogeneity and sensitivity. It should be noted that, in the head-up vertical position of the rat, the lower end ring of the birdcage is more significantly loaded by the animal’s neck and body. Animal body and limbs are also in close proximity to the RF cables passing through the cradle and connecting the coil to the probe body. Although anatomy outside of the brain is not of interest in this application, it might be expected that the RF loads presented by the neck and shoulders may impact B1 homogeneity, or that proximity of other body parts to RF cables may interact with common mode currents in cable shield jackets. Nevertheless, B1 homogeneity remained good for this specimen and other live animals that were studied with the coil. Coil resonance remained unperturbed when RF cables were touched by hand or by various parts of the animal body. The grounding of the birdcage RF shield to the drive cable jacket [22–24] removed interaction between the coil resonance and the common mode currents in the cable jacket, forgoing the baluns and cable traps that are often used in small animal coils [20, 21].

Figure 6.

The axial slices of a multi-slice FSE image of an in vivo rat brain with an ischemic stroke (hyperintensities in the upper cortical region of the last two slices). The rat was anesthetized, and the image was acquired with respiratory gating. The following acquisition parameters were applied: TE = 26 ms, TR = 6000 ms, FOV = 2.56 × 2.56 cm, NEX = 2, RARE factor = 4, acquisition time = 12.8 min. The in-plane resolution is 100×100 µm2 with a 500 µm slice thickness.

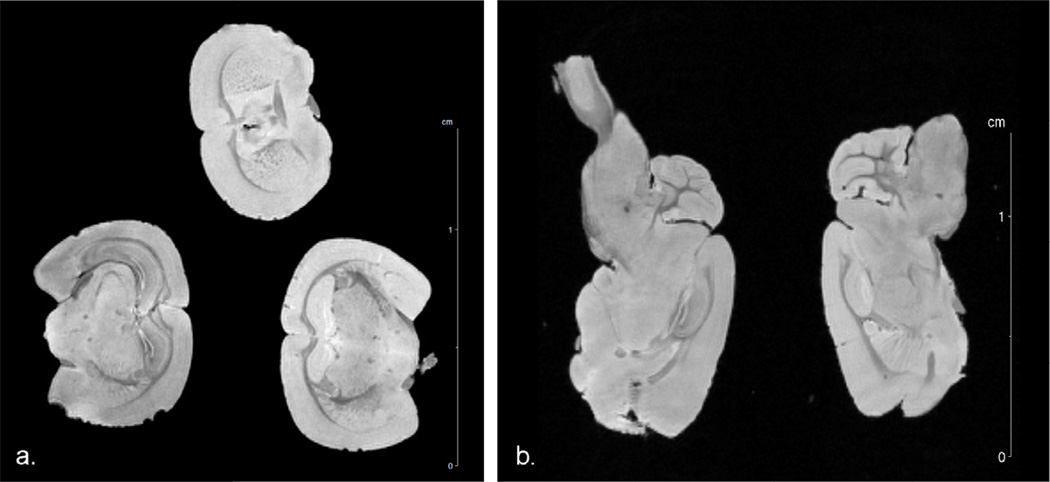

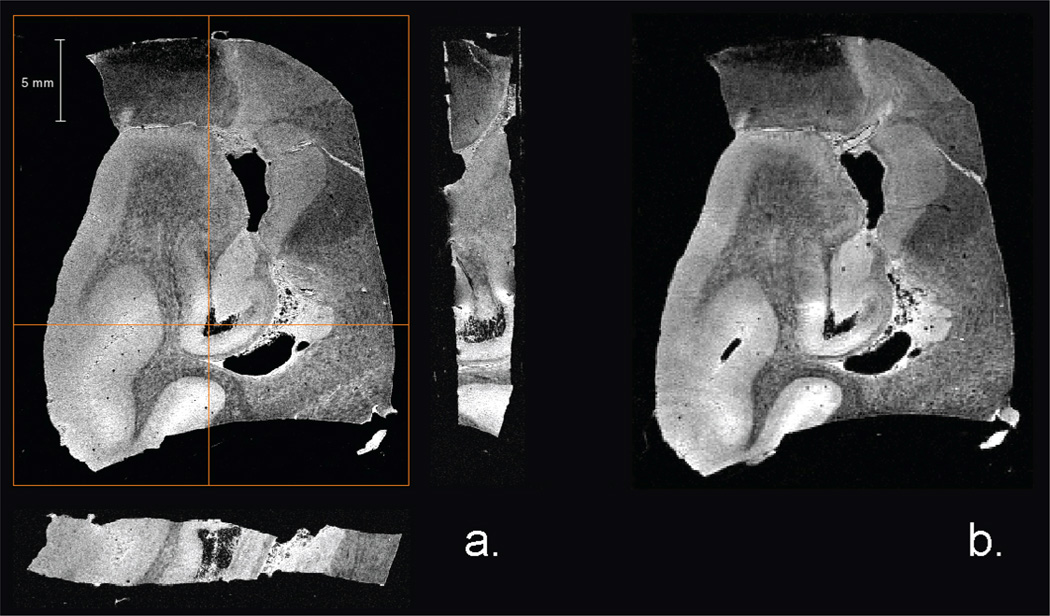

Representing a somewhat lighter RF load, Fig. 7 shows axial and sagittal partitions through a T2*-weighted 3D GRE dataset of three fixed mouse heads immersed in a non-protonated fluorocarbon. As well as good structural contrast, high resolution images of the fixed mouse brains again demonstrate good homogeneity and sensitivity for an intermediate RF load. Likewise, Fig. 8 displays partitions through a 3D GRE dataset acquired from a postmortem human Alzheimer’s hippocampus. This human specimen offers an even lighter RF load than either the in vivo rat or ex vivo mouse brains, while also providing an asymmetric sample geometry. Under these conditions, the sliding ring coil could still be impedance matched and continued to perform with good homogeneity and signal-to-noise ratios. Images of the diseased hippocampus, whether acquired at high temporal resolution or high spatial resolution, display good delineation of hippocampal structures, including microvasculature and disease features such as alteration of the dentate gyrus and destruction of cellular layers [31]. In all instances presented above, the sliding ring birdcage was retunable to 900 MHz for all samples without noticeable distortions in B1 field intensity.

Figure 7.

Partitions of a 3D GRE dataset of three perfused mouse brains imaged in simultaneously with the sliding ring coil. a) Coronal image. b) Saggital images slicing mid-way through the lower two brains on the left image. Brains are immersed in a proton-free fluorocarbon within separate 10 mm NMR tubes. Acquisition parameters are: TE = 7.5 ms, TR = 150 ms, α = 25°, FOV = 2 × 2 × 2 cm3, NEX = 2, acquisition time = 5.5 hours, isotropic resolution = 78 µm. Average SNR values in coronal image are 126.1 ± 10.7 for gray matter areas and 97.8 ± 7.7 for white matter areas.

Figure 8.

Partitions of 3D GRE datasets of postmortem human hippocampal section from an Alzheimer’s patient. a) Coronal, sagittal and axial high resolution images acquired with TE = 7.5 ms, TR = 50 ms, FA = 10°, FOV = 3 × 3 × 0.6 cm3, NEX = 1, acquisition time = 1 hr, isotropic resolution = 50 µm; average SNR values are 17.5 and 11.3 for gray and white matter areas, respectively. b) Coronal image acquired with TE = 10 ms, TR = 25 ms, FA = 5°, FOV = 3 × 3 × 0.6 cm3, NEX = 1, acquisition time = 7.5 min, isotropic resolution = 100 µm.

Conclusion

A low-pass birdcage volume coil with an adjustable sliding tuner ring was constructed as a general purpose user probe for imaging a variety of biological samples at 21.1 T. This high-frequency volume coil with 33 mm aperture can be impedance matched under a varied range of loading conditions without sacrificing the B1 homogeneity, which is maintained by the simultaneous alteration of the distributed capacitance between the tuner ring and conductive legs. Such configuration permits implementing a birdcage coil with a large number of conductive legs that can be tuned simultaneously. Although other designs including volume, surface and array coils can be made to operate at high frequency, the sliding ring setup described here provides the wide tuning range and flexibility to use a single volume coil for samples of different sizes and RF loading conditions. The coil was excited at its end ring with no direct return path between the shield of the drive cable and the birdcage elements. The outer jacket of drive cable was joined to the coil’s Faraday shield, stabilizing and isolating the resonance from the impacts of common mode RF currents flowing in the drive cable’s shield and eliminating the need for cable or balun traps commonly used to suppress them. Practical applications were demonstrated at 21.1 T by obtaining high resolution images on different samples, such as the in vivo brain of an adult rat, ex vivo mouse brains and postmortem human tissues. Although the sliding ring coil was conceived to accommodate in vivo specimens, these ex vivo applications underscore the utility of the design to a wide range of biomedical applications, as well as to the emerging field of zoological MRI [36]. Among potential specimen, morphological or pathological studies of excised tissue can be conducted on multiple samples simultaneously to take advantage of the available coil FOV (both in the longitudinal and transverse directions) and of high magnetic field to improve overall throughput as has been done elsewhere [37]. While other studies [3–6] have implemented surface coil and phased-array RF designs to achieve satisfactory small animal imaging at high fields, the present study demonstrates that a birdcage coil can still be used to achieve homogeneous images in spite of the higher operating frequency of 900 MHz and diameters of greater than 30 mm.

In vivo vertical bore rat MRI probe for high field 21.1-T magnet is presented

Volume coil uses sliding tuner ring to accommodate diverse biological specimens

Volume coil homogeneity remains good across diverse sample loads

Variety of practical in vivo and ex vivo applications are demonstrated at 21.1 T

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory through Cooperative Agreement (DMR-0654118) with the National Science Foundation and the State of Florida as well as the NHMFL User Collaboration Grants Program (to SCG). The authors would like to thank Richard Desilets for careful machining of all probe parts, Barbara Beck and Dr. Victor Schepkin for helpful comments and suggestions, as well as Drs. Dennis Dickson, Zbigniew Wszoleck and Karunya Kanimalla of the Mayo Clinic for tissue specimens. C.Q. is grateful for financial support from Bruker Biospin Corp. and the National Institutes of Health, NINDS.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fu R, Brey WW, Shetty K, Gor'kov PL, Saha S, Long JR, Grant SC, Chekmenev EY, Hu J, Gan Z, Sharma M, Zhang F, Logan TM, Bruschweller R, Edison A, Blue A, Dixon IR, Markiewicz WD, Cross TA. Ultra-wide bore 900 MHz high-resolution NMR at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory. J. Magn. Reson. 2005;177:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schepkin VD, Brey WW, Gor’kov PL, Grant SC. Initial in vivo rodent sodium and proton MR imaging at 21.1 T. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2010;28:400–407. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li S, Shen J. Integrated RF probe for in vivo multinuclear spectroscopy and functional imaging of rat brain using an 11.7 Tesla 89 mm bore vertical microimager. Magn. Reson. Mater. Phy. 2005;18:119–127. doi: 10.1007/s10334-005-0103-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behr VC, Weber T, Neuberger T, Vroemen M, Weidner N, Bogdahn U, Haase A, Jakob PM, Faber C. High-resolution MR imaging of the rat spinal cord in vivo in a wide-bore magnet at 17.6. Tesla, Magn. Reson. Mater. Phy. 2004;17:353–358. doi: 10.1007/s10334-004-0057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gareis D, Neuberger T, Behr VC, Jakob PM, Faber C, Griswold MA. Transmitreceive coil-arrays at 17.6 T, configurations for 1H, 23Na, and 31P MRI. Concepts Magn. Reson. 2006;29B:20–27. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gareis D, Wichmann T, Lanz T, MeIkus G, Horn M, Jakob PM. Mouse MRI using phased-array coils. NMR Biomed. 2007;20:326–334. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong WH, Sukumar S. “Millipede” Imaging Coil Design for High Field Micro Imaging Applications. Proc. Intl. Soc. Magn. Reson. Med. 2000;8:1399. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong WH. Millipede coils. 6,285,189. U.S. Patent. 2001

- 9.Hayes CE, Edelstein WA, Schenck JF, Mueller OM, Eash M. An efficient, highly homogenous radiofrequency coil for whole-body NMR imaging at 1.5 T. J. Magn. Reson. 1985;63:622–628. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tropp J. The theory of the birdcage resonator. J. Magn. Reson. 1989;82:51–62. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pascone RJ, Garcia BJ, Fitzgerald TM, Vullo T, Zipagan R, Cahill PT. Generalized electrical analysis of low-pass and high-pass birdcage resonators. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 1991;9:395–408. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(91)90428-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leifer MC. Resonant modes of the birdcage coil. J. Magn. Reson. 1997;124:51–60. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chin CL, Collins CM, Li S, Dardzinski BJ, Smith MB. Design of specifiedgeometry birdcage coils with desired current pattern and resonant frequency. Concepts Magn. Reson. 2002;15B:156–163. doi: 10.1002/cmr.10030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayes CE. Radio frequency field coil for NMR. 4,694,255. US Patent No. 1987

- 15.Pimmel P, Brugue A. A hybrid bird cage resonator for sodium observation at 4.7 T. Magn. Reson. Med. 1992;24:158–162. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910240116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Su S, Saunders JK. A new miniaturizable birdcage resonator design with improved electric-field characteristics. J. Magn. Reson. 1996;110B:210–212. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1996.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vaughan JT, Hetherington HP, Otu JO, Pan JW, Pohost GM. High-frequency volume coils for clinical NMR imaging and spectroscopy. Magn. Reson. Med. 1994;32:206–218. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910320209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang XL, Ugurbil K, Chen W. A microstrip transmission line volume coil for human head MR imaging at 4 T. J. Magn. Reson. 2003;161:242–251. doi: 10.1016/s1090-7807(03)00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dardzinski BJ, Li S, Collins CM, Williams GD, Smith MB. A birdcage coil tuned by RF shielding for application at 9.4 T. J. Magn. Reson. 1998;131:32–38. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1997.1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peterson DM, Beck BL, Duensing CR, Fitzsimmons JR. Common mode signal rejection methods for MRI: Reduction of cable shield currents for high static magnetic field systems. Concepts Magn. Reson. 2003;19B:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seeber DA, Jevtic J, Menon A. Floating Shield Current Suppression Trap. Concepts Magn. Reson. 2004;21B:26–31. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leifer MC, Hartman SC. Shielded drive for balanced quadrature bird cage coil. 6,011,395. U.S. Patent. 2000

- 23.Tropp J. Dissipation, resistance, and rational impedance matching for TEM and birdcage resonators. Concepts Magn. Reson. 2002;15:177–188. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beck BL, Jenkins KA, Fitzsimmons JR. Geometry Comparisons of an 11-T Coaxial Reentrant Cavity (ReCav) Coil. Concepts Magn. Reson. 2003;18B:24–27. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gor'kov PL, Qian C, Beck BL, Clark D, Masad IS, Schepkin VD, Grant SC, Brey WW. A modular MRI probe design for large rodent neuroimaging at 21.1 T (900 MHz) Proc. Intl. Soc. Magn. Reson. Med. 2009;17:2952. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stollberger R, Wach P, McKinnon G, Justich E, Ebner F. RF-field mapping in vivo. Proc. Soc. Magn. Reson. Med. 1988;7:106. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Insko EK, Bolinger L. B1 mapping. Proc. Soc. Magn. Reson. Med. 1992;11:4302. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cunningham CH, Pauly JM, Nayak KS. Saturated double-angle method for rapid B1+ mapping. Magn. Reson. Med. 2006;55:1326–1333. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olson DL, Peck TL, Webb AG, Margin RL, Sweedler JV. High-resolution microcoil 1H-NMR for mass-limited, nanoliter-volume samples. Science. 1995;270:1967–1970. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma Y, Hof PR, Grant SC, Blackband SJ, Bennett R, Slatest L, McGuigan MD, Benveniste H. A three-dimensional digital atlas database of the adult C57BL/6J mouse brain by magnetic resonance microscopy. Neuroscience. 2005;134:1203–15. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schweitzer KJ, Foroutan P, Dickson DW, Broderick DF, Klose U, Berg D, Wszolek ZK, Grant SC. A novel approach to dementia: High Resolution 1H MRI of the Human Hippocampus Performed at 21.1 T. Neurology. 2010;74:1654. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181df09c9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fujioka S, Murray ME, Foroutan P, Schweitzer KJ, Dickson DW, Grant SC, Wszolek ZK. Magnetic resonance imaging with 21.1T and pathological correlations – diffuse Lewy body disease. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2011;51:603–607. doi: 10.5692/clinicalneurol.51.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tofts PS. Standing waves in uniform water phantoms. J. Magn. Reson. 1994;104B:143–147. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoult DI, Phil D. Sensitivity and Power Deposition in a High-Field Imaging Experiment. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2000;12:46–67. doi: 10.1002/1522-2586(200007)12:1<46::aid-jmri6>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang QX, Wang J, Zhang X, Collins CM, Smith MB, Liu H, Zhu XH, Vaughan JT, Ugurbil K, Chen W. Analysis of wave behavior in lossy dielectric samples at high field. Magn. Reson. Med. 2002;47:982–989. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ziegler A, Kunth M, Mueller S, Bock C, Pohmann R, Schr�der L, Faber C, Giribet G. Application of magnetic resonance imaging in zoology. Zoomorphology. 2011;130:227–254. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang X, Schneider JE, Portnoy S, Bhattacharya S, Henkelman RM. Comparative SNR for high-throughput mouse embryo MR microscopy. Magn. Reson. Med. 2010;63:1703–1707. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]