Abstract

We investigated the role that knowledge activation and sentence mapping play in how readers represent fictional characters' emotional states. The subjects read stories that described concrete actions, such as a main character stealing money from a store where his best friend worked and later learning that his friend had been fired. By manipulating the content of the stories (i.e. writing stories that implied different emotional states), we affected what emotional knowledge would be activated. Following each story, the subjects read a target sentence that contained an emotion word. By manipulating the emotion word in each target sentence (i.e. whether it matched vs mismatched the emotional state implied by the story), we affected how easily subjects could map the target sentence onto their developing mental structures. In Experiment 1, we further isolated the role of knowledge activation from the role of sentence mapping with a density manipulation. When the subjects read many emotional stories, they more widely activated their knowledge of emotional states. Using a proportionality manipulation in Experiment 2, we demonstrated that this result was not due to the subjects' strategies.

Introduction

Consider the following fictional story:

Joe worked at the local 7–11 store, to get spending money while in school. One night, his best friend, Tom, came in to buy a soda. Joe needed to go back to the storage room for a second. While he was away, Tom noticed the cash register was open. From the open drawer Tom quickly took a ten dollar bill. Later that week, Tom learned that Joe had been fired from the 7–11 store because his cash had been low one night.

A reader who successfully comprehends this story will build a mental representation of it. How are such mental representations built? According to Gernsbacher (1990), reading stories activates memory nodes, which represent previously stored knowledge. Memory nodes are the building blocks of mental “structures”, which are built by mapping incoming information (e.g. sentences) onto a mental structure. Similarly, according to Kintsch (1988), comprehension involves the mental processes of “construction” (activation of previously stored knowledge) and “integration” (a process that combines the activated knowledge with the information provided by the story). Thus, common to models of story comprehension is the idea that readers activate previously stored knowledge and use that knowledge to map incoming sentences onto their developing mental representations.

While reading the story about Joe, Tom and the 7–11 store, readers might activate various types of previously stored knowledge to construct their mental structures. Perhaps they activate previously stored spatial knowledge (Glenberg, Meyer & Lindem, 1987; Mani & Johnson-Laird, 1982; Morrow, Bower & Greenspan, 1989; Morrow, Greenspan & Bower, 1987). If so, then reading the sentence, While Joe was away, Tom noticed the cash regiser was open [and] quickly took a ten dollar bill, might stimulate readers to activate knowledge about the typical spatial layout of convenience stores. With that knowledge activated, they might map onto their mental structures a representation of the 7–11 store such that Tom could not be seen by Joe when Tom was in the storage room and Joe was near the cash register.

Perhaps readers also activate temporal knowledge (Anderson, Garrod & Sanford, 1983). If so, then reading the expression, Later that week, [Tom learned that Joe had been fired. . .], might stimulate readers to activate knowledge about the activities that can occur within the period, one week. With that knowledge activated, they might map onto their mental structures a mental time-frame for the story that allows other events to occur between the time when Tom took the ten dollar bill and the time he learned that Joe had been fired (e.g. Joe's boss learned of the missing cash).

In Gernsbacher, Goldsmith and Robertson (1992), we investigated whether readers activate another type of knowledge while comprehending stories: We investigated whether readers activate knowledge about human emotions and use that activated knowledge to build mental representations of fictional characters' emotional states. If so, then reading the sentence, Later that week, Tom learned that Joe had been fired from the 7–11 store because his cash had been low one night, might stimulate readers to activate knowledge of how someone feels when he finds out that his best friend was fired for something he did. With that knowledge activated, they might map onto their mental structures a representation of the fictional character Tom feeling the emotional state, guilt.

In Gernsbacher et al. (1992), we tested this hypothesis. We began by writing 24 experimental stories. Each experimental story was intended to stimulate readers to activate knowledge about a particular emotional state. But, importantly, these emotional states were implied without explicit mention of any emotion. The experimental stories did describe concrete actions, such as Tom going to the 7–11 store, Joe going to the storage room, Tom taking the ten dollar bill, and Tom learning that Joe had been fired. But never was there any mention of emotion until a final “target” sentence.

A target sentence occurred after the main body of each of the 24 experimental stories. Each target sentence contained an emotion word, e.g. guilt, as in It would be weeks before Tom's guilt would subside. We manipulated whether the emotion word in the target sentence matched the emotional state implied in the story (e.g. guilt) or whether the emotion word mismatched the emotional state implied in the story (e.g. pride).

In addition to the 24 experimental stories, each subject read 24 filler stories. The filler stories were written in the same style as the experimental stories, but the filler stories were not intended to activate information about any emotional state; they were relatively neutral, for example:

Today was the day Tyler was going to plant a garden. He put on his work clothes and went out to the shed to get the tools. The ground was all prepared so he began planting right away. It was a small garden, but then he didn't really need a large one. It was large enough to plant a few of his favourite vegetables. Maybe this year he'd plant some flowers, too.

A filler story preceded each experimental story (i.e. the subjects read a filler story before reading each experimental, emotional story).

In our first experiment (Gernsbacher et al., 1992), the mismatching emotion words were what we called the “perceived converses” of the matching emotion words. By this we meant that the matching and mismatching emotion words were opposite along one important dimension, but they were almost identical along other dimensions. The dimension along which they were opposite was their affective valence: One emotion word had a negative affective valence (e.g. guilt) and the other had a positive affective valence (e.g. pride). The dimensions along which they were almost identical were their intensity, duration, relevance to self vs others, temporal reference (to events in the past, present or future), and so forth (Frijda, 1986). The 12 pairs of converse emotional states were as follows: guilt–pride, boredom–curiosity, sadness–joy, shyness–confidence, restlessness–contentment, fear–boldness, depression–happiness, disgust–admiration, envy–sympathy, callousness–care, despair–hope and anger–gratitude.

For each pair of converse emotional states, we wrote two stories. For one story, one member of the converse states matched, whereas the other member mismatched; for the other story, the opposite was true. For instance, we wrote two stories for the pair guilt–pride. The story for which guilt matches and pride mismatches was illustrated above. The other story, for which pride matches and guilt mismatches, was the following:

Paul had always wanted his brother, Luke, to be good in baseball. So Paul had been coaching Luke after school for almost two years. In the beginning, Luke's skills were very rough. But after hours and hours of coaching, Paul could see great improvement. In fact, the improvement had been so great that at the end of the season, at the Little League Awards Banquet, Luke's name was called out to receive the Most Valuable Player Award.

For this story, a target sentence with a matching emotion word would be It would be weeks before Paul's pride would subside, whereas a target sentence with a mismatching emotion word would be It would be weeks before Paul's guilt would subside.

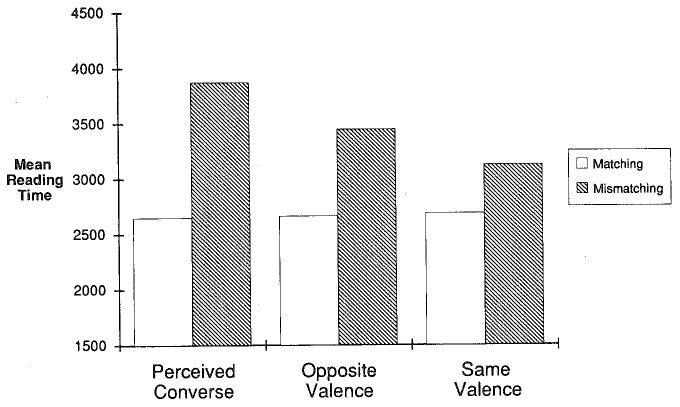

We measured how long subjects needed to read each story's target sentence, and the subjects' mean reading times are displayed in the two leftmost bars of Fig. 1. As the two leftmost bars illustrate, the subjects read the target sentences considerably more rapidly when they contained an emotion word that matched the emotional state implied in the story as opposed to when the target sentences contained an emotion word that mismatched the emotional state implied in the story.

Fig. 1.

The subjects' mean reading times (msec) from Gernsbacher et al. (in press, experiments 1 and 2) and from a previously unreported experiment. The two leftmost bars illustrate the reading times when the matching and mismatching emotion words were “perceived” converses (e.g. guilt–pride. The two middle bars illustrate the reading times when the matching and mismatching emotion words were opposite in affective valence, but not perceived complements (e.g. guilt–hope). The two rightmost bars illustrate the reading times when the matching and mismatching emotion words shared their affective valence (e.g. guilt–shyness).

In another, previously unreported experiment, we altered the nature of the mismatching emotion words. In this experiment, the mismatching emotion words were not converses of the matching emotion words (as they had been in the first experiment of Gernsbacher et al., 1992). Rather, in this experiment, the matching and mismatching emotion words were dissimilar along the dimensions that the converses shared, as well as being opposite in their affective valence (i.e. negative vs positive).

For instance, following the story about Tom and the 7–11 store, a target sentence with a matching emotion word would be, It would be weeks before Tom's guilt would subside, just as it was in the first experiment of Gernsbacher et al. (1992). But a target sentence with a mismatching emotion word would be, It would be weeks before Tom's hope would subside. Notice that hope (a mismatching emotion word) has the opposite affective valence of guilt (the matching emotion word), but hope and guilt are not converses. In this experiment, the emotional states were paired in the following way: guilt–hope, pride–shyness, envy–joy, sympathy–anger, disgust–gratitude, admiration–callousness, care–restlessness, despair–contentment, happiness–fear, curiosity–sadness, confidence–depression and boredom–boldness.

The results of this experiment are displayed in the two middle bars of Fig. 1. As the two middle bars illustrate, the subjects read the target sentences considerably more rapidly when they contained matching as opposed to mismatching emotion words. However, the subjects read the mismatching target sentences more rapidly in this experiment than they did in the first experiment. Recall that the difference between these two experiments was the nature of the mismatching emotion words: In the first experiment, the mismatching emotion words were the converses of the matching emotion words (e.g. guilt–pride); in this experiment, the matching and mismatching emotion words were opposite in affective valence and dissimilar along the dimensions that the converses shared (e.g. guilt–hope).

In a third experiment (Gernsbacher et al., 1992, experiment 2), we again altered the nature of the mismatching emotion words. In this experiment, the mismatching emotion words were the same affective valence as the matching emotion words, although the mismatching emotion words were less appropriate than the matching emotion words. For instance, following the story about Tom and the 7–11 store, a mismatching target sentence was It would be weeks before Tom's shyness would subside. Notice that shyness (a mismatching emotion word) has the same affective valence as guilt (the matching emotion word); however, given the knowledge of how someone feels when he finds out that his best friend was fired for something he did, shyness is a less likely emotional state than guilt. In this experiment, the emotional states were paired in the following way: guilt–shyness, pride–curiosity, boredom–anger, restlessness–disgust, depression–fear, callousness–despair, sadness–envy, joy–boldness, sympathy–happiness, care–contentment, hope–admiration and gratitude–confidence.

The results of this experiment are displayed in the two rightmost bars of Fig. 1. The subjects again read the target sentences more rapidly when they contained matching as opposed to mismatching emotion words, as we found in our other two experiments. However, the subjects read the mismatching target sentences more rapidly in this experiment than they did in the other two experiments.

The striking similarity among the three sets of data illustrated in Fig. 1 lies in the subjects' reading times for the matching target sentences. In each experiment, the subjects read the matching target sentences at approximately the same rate, regardless of the nature of the mismatching target sentences. The striking difference among these three sets of data lies in the subjects' reading times for the mismatching sentences. The more disparate the mismatching emotion words were to the implied emotional states, the more slowly the subjects read the target sentences containing those mismatching emotion words. When the mismatching emotion words were the converses of the implied emotional states, the subjects read the target sentences most slowly; when the mismatching emotion words were opposite in affective valence but not converses, the subjects read the target sentences less slowly; and when the mismatching emotion words were the same affective valence as the implied emotional states, the subjects read the target sentences most rapidly, although not as rapidly as they read target sentences containing matching emotion words.

We suggest that these data illustrate both the role that knowledge activation and the role that sentence mapping plays in readers' representations of fictional characters' emotional states. By manipulating the content of the stories (i.e. writing stories that implied different emotional states), we affected what emotional knowledge would be activated. Other data that we collected demonstrated that the stories (without the target sentences) were indeed powerful sources of knowledge activation.1 By manipulating the content of the target sentences, we affected how easily the subjects could map the target sentences onto their developing mental structures. When the target sentences contained matching emotion words, they were easiest to map – presumably because the knowledge activated by the stories and the content of the target sentences cohered. When the target sentences contained mismatching, and, in particular, converse emotional words, they were least easy to map – presumably because the knowledge activated by the stories and the content of the target sentences were incoherent. Target sentences that contained mismatching emotion words that were opposite in valence to the implied emotional states and target sentences that contained mismatching emotion words that were the same valence but less likely than the implied emotional states fell between those two extremes, in terms of subjects' ease in sentence mapping.

Although our previous experiments illustrated the roles that knowledge activation and sentence mapping play in how readers mentally represent fictional characters' emotional states, our previous experiments did not distinguish these two roles. The experiments we report here do. In our first experiment, we isolated the role that knowledge activation plays by manipulating the number of emotional stories that our subjects read. We assumed that the subjects' knowledge of emotional states would be more activated when they read more emotional stories than when they read fewer emotional stories. This greater activation of emotional knowledge should affect the subjects' reading time – but only to the mismatching sentences. We explain this prediciton in the next section.

Experiment 1

In our previous experiments, all of the subjects read 48 total stories. Half the stories (24) were experimental, emotional stories, and half were non-emotional, filler stories. In Experiment 1, we manipulated how frequently emotional stories occurred in the experiment. There were two conditions. In the high-density condition, 36 of the 48 stories were emotional stories, and only 12 were non-emotional, filler stories. In the low-density condition, only 12 of the 48 stories were emotional stories, and 36 were non-emotional, filler stories.

The data we analysed were reading times to the target sentences in the “common” set of 12 emotional stories (i.e. the 12 emotional stories that occurred in both the high- and low-density conditions). Of these 12 emotional stories, half had target sentences with matching emotion words, and half had target sentences with mismatching emotion words. The mismatching emotion words were the converses of the matching emotion words (e.g. guilt and pride), as they had been in the first experiment of Gernsbacher et al. (1992).

We predicted that the density manipulation would not affect reading times to the matching target sentences. This is because information about the implied (matching) emotional states would already be highly activated by the content of the stories; therefore, the matching emotional states could not be “helped” by the greater activation of emotional knowledge produced by the higher density of emotional stories. Neither could the activation level of the matching emotional states be “hurt” by the lesser activation of emotional knowledge produced by the lower density of emotional stories.

In contrast, we predicted that the density manipulation would affect reading times to the mismatching target sentences. This is because reading many emotional stories should greatly activate subjects' knowledge about emotional states; if so, even converse emotional states should be more activated when subjects read more emotional stories than when they read fewer. Therefore, we predicted that the mismatching sentences would be read more rapidly in the high-density condition than in the low-density condition (because the mismatching emotional states would be more activated in the high-density condition than in the low-density condition).

This predicted effect of the density manipulation on subjects' reading times for the mismatching sentences could not be attributable to ease in mapping. The mismatching sentences were the same in the high- and low-density conditions; therefore, any difference in reading times to the mismatching sentences must be a function of information that was already activated. And because the 12 common experimental stories (which preceded the target sentences) were the same in the high- and low-density conditions, any difference in knowledge activation must arise from sources beyond those stories (i.e. the filler emotional stories). We can observe the role of sentence mapping only by comparing conditions in which the target sentences (or experimental stories) differed. In Experiment 1, that comparison was provided by the matching vs mismatching emotion word manipulation.

Thus, in Experiment 1, we hoped to observe the role of knowledge activation by observing the effects of the density manipulation (high vs low). We hoped to observe the role of sentence mapping by observing the effects of the emotion word manipulation (matching vs mismatching).

Method

Subjects

The subjects were 160 University of Oregon undergraduates who participated as one means of fulfilling a course requirement. All were native American English speakers, and no subject participated in more than one of the experiments described in this paper. Eighty subjects were randomly assigned to the high-density condition, and 80 subjects were randomly assigned to the low-density condition.

Materials

Our stimuli included the 24 emotional stories used in the first experiment of Gernsbacher et al. (1992). We selected 12 of these emotional stories for the common set of emotional stories (the 12 emotional stories that occurred in both the high- and low-density conditions). For the high-density condition, we wrote 12 additional emotional stories.

There were four target sentences for each pair of 12 common emotional stories. Two of the four target sentences shared their sentence frame, e.g. It would be weeks before Tom's guilt would subside and It would be weeks before Tom's pride would subside. The other two target sentences also shared their sentence frame, e.g. Hearing that made Tom very guilty and Hearing that made Tom very proud. We needed four target sentences so that we would not be forced to repeat target sentences when we presented both stories (e.g. the story about Joe, Tom and the 7–11 store that implied guilt and the story about Paul, Luke and the Little League Banquet that implied pride).

Thus, all the subjects read the story about Tom, Joe and the 7–11 store, but 25% of the subjects read It would be weeks before Tom's guilt would subside, 25% read It would be weeks before Tom's pride would subside, 25% read Hearing that made Tom very guilty, and 25% read Hearing that made Tom very proud. Similarly, all of the subjects read the story about Paul, Luke and the Little League Awards Banquet, but 25% of the subjects read It would be weeks before Paul's pride would subside, 25% read It would be weeks before Paul's guilt would subside, 25% read Hearing that made Paul very proud, and 25% read Hearing that made Paul very guilty.

Our stimuli also included the 24 non-emotional, filler stories that Gernsbacher et al. (1992) had used. We selected 12 of these non-emotional, filler stories for a common set of filler stories (i.e. the 12 non-emotional, filler stories that occurred in both the high- and low-density conditions). For the low-density condition, we wrote 12 additional non-emotional filler stories. Thus, in the high-density condition, 36 of the 48 stories (75%) that the subjects read were emotional stories, and 12 of the stories (25%) were non-emotional filler stories; in the low-density condition, 12 of the 48 stories (25%) that the subjects read were emotional stories, and 36 of the stories (75%) were non-emotional, filler stories. As mentioned previously, all filler stories were written in the same style in which the emotional stories were written, but the non-emotional filler stories were not intended to induce readers to activate emotional knowledge. The filler stories were distributed among the emotional stories in both the high- and low-density conditions.

We formed eight material sets by varying (1) the density of emotional vs non-emotional stories, (2) whether the emotion word in the target sentence matched vs mismatched the implied emotional state, and (3) which of the two sentence frames for each target sentence was presented.

Procedure

The subjects were tested individually in a session lasting 35–45 min. From a computer screen, the subjects read instructions, which told them that the experiment involved reading several short stories, and their task was to read each story at a natural reading rate. To encourage their comprehension, the subjects were required to write a suitable continuation for some of the stories. They did not know in advance which stories they would have to continue.

At the beginning of each story, the message “READY?” appeared in the centre of the screen. When the subjects pressed a response key, the message “READY?” disappeared. Then each sentence of a story appeared in the centre of the screen. After reading each sentence, the subjects pressed a response key, which caused that sentence to disappear and the next sentence to appear. After the last sentence of the story, either the words “Please Continue the Story” or the words “Short Wait” appeared. Whenever the words “Please Continue the Story” appeared, the subjects were instructed to pick up a nearby pencil and write a suitable continuation on a nearby clipboard. They were given 20 sec to write each continuation. The subjects wrote continuations for 12 stories (half emotional and half non-emotional). They had to read a practice story and write a continuation before proceeding with the actual experiment.

Results

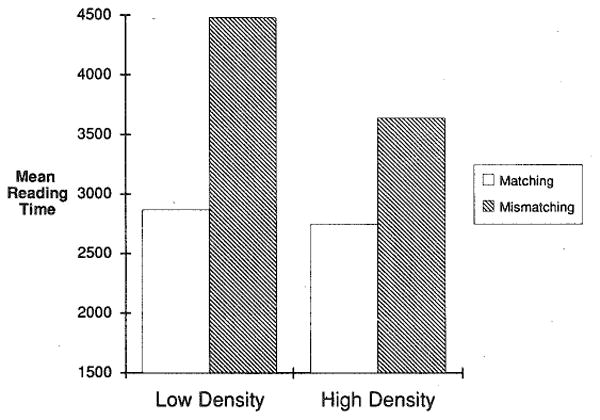

Figure 2 displays the subjects' mean reading times for the target sentences when they contained matching vs mismatching emotion words in the two density conditions. As Fig. 2 illustrates, the subjects read the target sentences considerably more rapidly when they contained matching as opposed to mismatching emotion words [min F'(l,71) = 99.34, P < 0.001]. This was the case in both the high-density condition [min F'(1,125) = 22.81, P < 0.001] and the low-density condition [min F'(l,115) = 45.10, P < 0.001]. This result suggests that readers can more easily map target sentences onto their developing mental structures when those target sentences contain matching as opposed to mismatching emotion words.

Fig. 2.

The subjects' mean reading times (msec) in Experiment 1. The two leftmost bars illustrate the subjects' reading times in the low-density condition (25% emotional stories, 75% non-emotional tiller stories). The two rightmost bars illustrate the subjects' reading times in the high-density condition (75% emotional stories, 25% non-emotional filler stories).

Figure 2 also illustrates the effect of the density manipulation. As Fig. 2 illustrates, the density manipulation did not affect the subjects' reading times for the matching target sentences (all Fs < 1). In contrast, the density manipulation did affect the subjects' reading times for the mismatching target sentences – mismatching target sentences were read more rapidly in the high-density condition than in the low-density condition [min F'(l,78) = 8.39, P < 0.01]. This different effect of the density manipulation on the matching vs mismatching target sentences was manifested in a reliable interaction [min F'(l,71) = 8.16, P < 0.01].

Thus, even when the sentences contained converse mismatching emotion words, they were read more rapidly when the subjects read more emotional stories. We attribute this result to knowledge activation, not sentence mapping, because the mismatching sentences and the experimental stories were the same in the high- and low-density conditions; therefore, any difference in reading times must have been produced by factors outside the 12 experimental stories and their target sentences. We suggest that reading more emotional stories more strongly activates subjects' knowledge of emotional states, whereas reading fewer emotional stories less strongly activates subjects' knowledge of emotional states. This greater vs lesser activation of emotional knowledge affected the subjects' reading times only to the mismatching sentences because information about the implied (matching) emotional states was already highly activated by the content of the stories.

However, a counter-explanation for the subjects' faster reading times to the mismatching sentences in the high- vs low-density condition is that subjects adopted a strategy. In the high-density condition, the subjects read more mismatching target sentences. Although the subjects also read more matching target sentences in the high-density condition, perhaps the higher incidence of mismatching sentences encouraged them to adopt a strategy for dismissing them or reading them less thoroughly.

One way to investigate this counter-explanation is to manipulate the proportion of matching vs mismatching target sentences. The logic underlying a proportion manipulation is simple: If a certain type of experimental trial occurs rarely, the subjects are unlikely to adopt a strategy for that type of trial. But if a type of trial occurs frequently, they are likely to adopt a strategy for responding to that type of trial – if the cognitive process tapped by that type of trial is under the subjects' strategic control.

For instance, consider the following experimental task: The subjects are shown pairs of letter strings (e.g. bortz-blaugh) and it is their task to decide whether or not each member of the pair is a word. On some trials, both members are words, and, on some of the trials in which both members are words, the two words are semantically related, e.g. bread–butter. A classic finding is that subjects respond to the second letter string more rapidly when it is a member of a related pair (Meyer & Schvaneveldt, 1971). For example, subjects respond to butter more rapidly when it is preceded by bread than when it is preceded by nurse.

Now, consider the following manipulation: In a low-probability condition, only one-eighth of the word pairs is related (bread–butter) and seven-eighths are unrelated (nurse–butter). In an equal probability condition, half the word pairs are related, and half are unrelated; and in a high-probability condition, the majority of the words are related, and only a small proportion is unrelated. In each condition, the subjects recognise the second word of the pair more rapidly if the pair is related, but the advantage is a function of the proportion of related trials. In the low-probability condition, the advantage is smallest; in the high-probability condition, the advantage is greatest (Tweedy, Lapinsky & Schvaneveldt, 1977). Presumably, the high proportion of related words encourages the subjects to adopt a strategy for capitalising on the words' relations.

However, subjects do not always adopt a strategy, even when there is a high proportion of a particular type of trial. Subjects only adopt a strategy if they can. For instance, in a bread–butter experiment, subjects typically adopt a beneficial strategy when there is a high proportion of related trials. However, they do not adopt a strategy if they are not given enough time to process the first word of the pair; without enough time to process the first word, there is no difference between the low-, equal- or high-probability conditions (den Heyer, Briand & Dannenbring, 1983). In other words, there is no effect of the proportion manipulation.

Similarly, a proportion manipulation does not affect how likely it is that subjects will access the less-frequent vs more-frequent meaning of an ambiguous word, e.g. the river's edge meaning of the word bank against the monetary meaning. According to Simpson and Burgess (1985), activating the less- vs more-frequent meaning of an ambiguous word is not under subjects' strategic control; therefore, response times are unaffected by the probability manipulation.

In Experiment 2, we performed a probability manipulation to discover whether the subjects' reading times for the mismatching sentences in the high-density condition of Experiment 1 were due to a strategy the subjects may have adopted for dismissing or not fully attending to those mismatching sentences. In Experiment 2, we manipulated the proportion of matching vs mismatching target sentences while holding constant the density of emotional stories. We used the highest possible density of emotional stories – all stories that the subjects read were emotional stories. And we again manipulated the emotion words in the target sentences (i.e. matching vs mismatching).

Experiment 2

All 36 stories that the subjects read in Experiment 2 were emotional stories; there were no non-emotional, filler stories. With these 36 emotional stories, we manipulated the proportion of final sentences that contained matching vs mismatching emotion words. There were three conditions. In the 75% mismatching condition, the final sentences for 27 stories contained mismatching emotion words, and the final sentences for only 9 stories contained matching emotion words. In the 50% mismatching condition, the final sentences for 18 stories contained matching emotion words, and the final sentences for an equal number of stories contained mismatching emotion words. In the 25% mismatching condition, the final sentences for only 9 stories contained mismatching emotion words, while the final sentences for 27 stories contained matching emotion words.

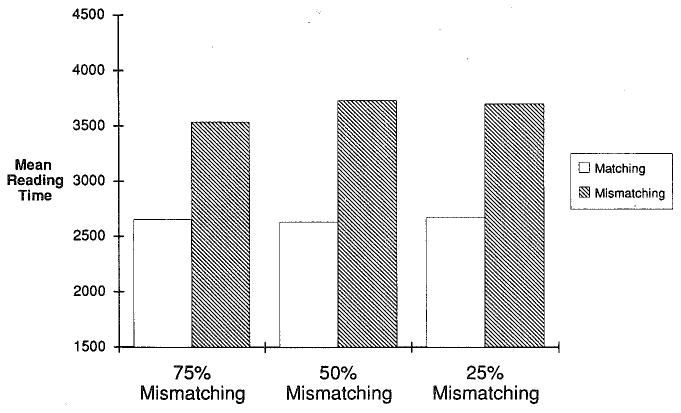

The data we analysed were reading times to the target sentences in a “common” set of 12 stories that occurred in all three probability conditions. Of these 12 emotional stories, half had target sentences with matching emotion words and half had target sentences with mismatching emotion words. All matching vs mismatching emotion words were converses (e.g. guilt and pride).

If the subjects' reading times to the mismatching target sentences in Experiment 1 manifested a strategy that the subjects adopted, then the proportion manipulation in Experiment 2 should have also affected their reading times. More specifically, the subjects should have read the mismatching target sentences most rapidly in the 75% mismatching condition and least rapidly in the 25% mismatching condition, with the reading times for the 50% mismatching condition being somewhere in between. In contrast, if the subjects' reading times to the mismatching target sentences in Experiment 1 manifested knowledge activation (produced by the density manipulation), then the proportion manipulation in Experiment 2 should not have affected the subjects' reading times. Instead, the only result we should have observed in Experiment 2 would have been a difference between the subjects' reading times to the matching vs mismatching target sentences. This result would reflect sentence mapping, which we predicted would be affected by the emotion word manipulation (matching vs mismatching), as we observed in all our previous experiments.

Method

Subjects

The subjects were 240 University of Oregon undergraduates who participated as one means of fulfilling a course requirement. Eighty subjects were randomly assigned to each of the 25%, 50% and 75% mismatching conditions.

Materials

The stimuli comprised the 36 emotional stories used in the high-density condition of Experiment 1. There were no non-emotional, filler stories. We formed 12 material sets by varying (1) whether the emotion word in the target sentence matched or mismatched the implied emotional state, (2) the proportion of matching vs mismatching target sentences, and (3) which of the two target sentence frames was presented.

Procedure

The procedure followed in Experiment 2 was the same as for Experiment 1.

Results

Figure 3 displays the subjects' mean reading times for the target sentences when they contained matching vs mismatching emotion words in the three proportion conditions. As Fig. 3 illustrates, in all three proportion conditions, the subjects read the target sentences considerably more rapidly when they contained matching as opposed to mismatching emotion words [min F'(l,36) = 82.96, P < 0.001]. However, as Fig. 3 also illustrates, the proportion manipulation did not affect either the subjects' reading times to the matching target sentences or their reading times to the mismatching target sentences (all Fs < 1.5). These data suggest that the effect of the high-density condition on the subjects' reading times to the mismatching sentences in Experiment 1 was not due to a strategy the subjects adopted.2

Fig. 3.

The subjects' mean reading times (msec) in Experiment 2. The two leftmost bars illustrate the subjects' reading times in the condition in which 75% of the stories had target sentences with matching emotion words; the two middle bars illustrate the subjects' reading times in the condition in which 50% of the stories had target sentences with matching emotion words; the two rightmost bars illustrate the subjects' reading times in the condition in which 25% of the stories had target sentences with matching emotion words.

Conclusions

These two experiments illustrate the roles that knowledge activation and sentence mapping play in how readers represent fictional characters' emotional states. Our first experiment, using a density manipulation, isolated the role of knowledge activation from the role of sentence mapping. Our second experiment, using a proportion manipulation, demonstrated that this result was not due to the subjects' strategies.

How is knowledge about emotional states acquired? How is it represented? And how is it activated? Although knowledge about emotional states might be represented as schemata (Schank & Abelson, 1977), an alternative to representing schemata is to represent original experiences only, albeit abstractly (Hintzman, 1988). Presumably, the subjects in our experiments had previously encounterd experiences (either personally or vicariously, e.g. through literature) that resembled the experiences we wrote about in our stimulus stories. Indeed, we constructed our stimulus stories so that they would be relevant to our undergraduate population of subjects. The stories revolved around typical undergraduate activities, such as going on a date, interviewing for a job, studying for exams, and living in a dorm.

When the subjects in our experiments originally encountered experiences (either personally or vicariously) that were similar to those reproduced in our stimulus stories, presumably the subjects themselves or the fictional characters experienced a resulting emotional state. These emotional states became part of the memory trace. Therefore, reading about similar experiences should have activated those memory traces, and the memory traces included information about the concomitant emotional states.

This hypothesis predicts that the more emotionally evoking situations one encounters, the more memory traces are stored and, therefore, the more emotional knowledge is available. Indeed, developmental studies demonstrate that older children are more adept than younger children at assessing the appropriate emotional state of a fictional character (Harris & Gross, 1988). Surely, individuals must differ in their ability to experience and interpret emotional states; most likely they also differ in their tendency to represent and activate emotional knowledge.

Our previous results (Gernsbacher et al., 1992) suggest something provocative about the organisation of emotional knowledge. In our previous experiments, the emotion words in the target sentences varied from emotion words that matched, to emotion words that were of the same affective valence but were less likely, to emotion words that were the converses of the implied emotional states. The converses of the implied emotional states were least likely to be activated (as in the pronunciation experiment), and sentences containing converse emotion words were most difficult to map (as in the reading time experiment). This result is provocative because, as we stated before, our pairs of converse emotional states were identical to each other along many dimensions, although they differed along the critical dimension of their affective valence. According to a simple feature tally, our pairs of converse emotion words were, ironically, more similar to each other than the emotion words we paired by only the criteria of opposite affective valence. For example, guilt shares more features with pride than guilt shares with hope. Similarly, envy shares more features with sympathy than envy shares with joy or than sympathy shares with anger. How such converses are mentally represented to produce the effects we observed is a question for future research.

Let us turn our discussion towards the process of sentence mapping. We envision mapping as something like creating an object out of papier-mâché. Each strip of papier-mâché is attached to the developing object. Each layered strip augments the developing object, and appendages can be built, layer by layer. We have proposed that comprehenders build structures and sub-structures in a similar way: Each piece of incoming information can be mapped onto a developing structure, so that each new piece of information augments the developing structure.

Why does mapping occur? According to the Structure Building Framework (Gernsbacher, 1990), mental structures are built of memory nodes, which represent previously stored memory traces and are activated by incoming stimuli. The initial activation of memory nodes forms the foundations of mental structures. Once foundations are laid, incoming information is often mapped on because the more the incoming information overlaps with the previously represented information, the more likely it is to activate similar memory nodes. That is why the more the incoming information coheres with the previous information, the easier it is to map.

But what happens when the incoming information is less coherent and, therefore, more difficult to map onto an existing mental structure, as was the case with our mismatching target sentences? In such cases, it might be impossible for readers to map that sentence onto their developing structures without drawing what Haviland and Clark (1974) have termed a “bridging” inference. In contrast to predictive or elaborative inferences, bridging, or what we shall call “coherence” inferences are drawn to resolve discrepancies.

For example, after reading the story about Joe, Tom and the 7–11 store, the subjects who read the target sentence It would be weeks before Tom's pride would subside, might have drawn a coherence inference to resolve the discrepancy between what they thought Tom should have been feeling and what the story said he felt. Coherence (or backward) inferences differ from predictive (or forward) inferences, and coherence inferences are more likely to be drawn during comprehension than predictive inferences (Duffy, 1986; McKoon & Ratcliff, 1986; O'Brien, Shank, Myers & Rayner, 1988; Potts, Keenan & Golding, 1988; Singer, 1979; 1980; Singer & Ferreira, 1983). We propose that drawing a coherence inference activates additional knowledge that can facilitate the mapping process. Clearly, the vital roles that knowledge activation and sentence mapping play in successful comprehension deserve more empirical attention.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH Research Career Development Award K04 NS-01376, Air Force Office of Sponsored Research Grants 89-0258 and 89-0305, and NIH Research Grant ROl NS-00694 (all awarded to the first author). We are indebted to Hill Goldsmith for stimulating conversations about this research. Caroline Bolliger, Sara Glover, Daren Jackson, Cindy Ly, Maureen Marron, Jon Shaw, Michael Stickler and Elizabeth Walsh helped test the subjects.

Footnotes

In the third experiment of Gernsbacher et al. (1990), we employed a laboratory task that many cognitive psychologists argue reflects only what is currently activated in readers' mental representations; it does not reflect how easily a stimulus (such as a target sentence) can be used to construct a representation. The task is simply to pronounce a printed word as rapidly as possible. Pronouncing a printed word is such an easy task that subjects do not attempt to integrate the word into their mental representations; they simply pronounce it as fast as they can. Including filler words that are unrelated to the stories (which we did) further discourages subjects from attempting to interpret the words vis-à-vis the ongoing story (Balota & Chumbley, 1984; Chumbley & Balota, 1984; Keenan, Potts, Golding & Jennings, 1990; Lucas, Tanenhaus & Carlson, 1990; Seidenberg, Waters, Sanders & Langer, 1984).

The subjects in the third experiment of Gernsbacher et al. (1992) read the same stories as the subjects read in the reading time experiments. However, unlike the reading time experiments, the experimental stories in the pronunciation task experiment were not followed by a target sentence that contained a matching or mismatching emotion word. Instead, at different points during both the experimental and filler stories, target words appeared on the screen, and the subjects' task was simply to pronounce each target word as rapidly as possible.

During each experimental story, two words appeared. One was a filler word, which was unrelated to the story, but the other was an emotion word that either matched or mismatched the implied emotional state, and it appeared immediately after the subjects had read the last line of the story; for instance, after the subjects had read Later that week, Tom learned that Joe had been fired from the 7–11 store because his cash had been low one night, the target word guilt or pride appeared on the screen. We found that target words were pronounced reliably more rapidly when they matched (e.g. guilt) as opposed to mismatched (e.g. pride) the characters' implied emotional states.

In Experiment 2, the proportion of mismatching target sentences varied considerably more widely than it had in Experiment 1. In Experiment 1, the proportion of mismatching target sentences varied only from 12.5% (in the low-density condition) to 37.5% (in the high-density condition); however, a large difference in the subjects' reading times was observed. In Experiment 2, the proportion of mismatching target sentences varied from 25 to 75%, yet no differences were observed.

References

- Anderson A, Garrod SC, Sanford AJ. The accessibility of pronominal antecedents as a function of episode shifts in narrative text. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1983;35A:427–440. [Google Scholar]

- Balota DA, Chumbley JI. Are lexical decisions a good measure of lexical access? The role of word frequency in the neglected decision stage. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1984;10:340–357. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.10.3.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chumbley JI, Balota DA. A word's meaning affects the decision in lexical decision. Memory & Cognition. 1984;12:590–606. doi: 10.3758/bf03213348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy SA. Role of expectations in sentence integration. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1986;12:208–219. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.12.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frijda NH. The emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Gernsbacher MA. Language comprehension as structure building. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gernsbacher MA, Goldsmith HH, Robertson RRW. Do readers mentally represent characters' emotional states? Cognition and Emotion. 1992;6:89–111. doi: 10.1080/02699939208411061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenberg A, Meyer M, Lindem K. Mental models contribute to foregrounding during text comprehension. Journal of Memory and Language. 1987;26:69–83. [Google Scholar]

- Harris PL, Gross D. Children's understanding of real and apparent emotion. In: Astingtio JW, Harris PL, Olson DR, editors. Developing theories of mind. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1988. pp. 295–314. [Google Scholar]

- Haviland SE, Clark HH. What's new? Acquiring new information as a process in comprehension. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 1974;13:512–521. [Google Scholar]

- den Heyer K, Briand K, Dannenbring GL. Strategic factors in a lexical-decision task: Evidence for automatic and attention-driven processes. Memory & Cognition. 1983;11:374–381. doi: 10.3758/bf03202452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hintzman DL. Judgments of frequency and recognition memory in a multiple-trace memory model. Psychological Review. 1988;95:528–551. [Google Scholar]

- Keenan JM, Potts GR, Golding J, Jennings T. Which elaborative inferences are drawn during reading? A question of methodologies. In: Balota DA, Flores d'Arcais GB, Rayner K, editors. Comprehension processes in reading. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.; 1990. pp. 377–402. [Google Scholar]

- Kintsch W. The role of knowledge in discourse comprehension: A construction-integration model. Psychological Review. 1988;95:163–182. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.95.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas MM, Tanenhaus MK, Carlson GN. Levels of representation in the interpretation of anaphoric reference and instrument inference. Memory & Cognition. 1990;18:611–631. doi: 10.3758/bf03197104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mani K, Johnson-Laird NJ. The mental representation of spatial descriptions. Memory & Cognition. 1982;4:305–312. doi: 10.3758/bf03209220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKoon G, Ratcliff R. Inferences about predictable events. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1986;12:82–91. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.12.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer DE, Schvaneveldt RW. Facilitation in recognizing pairs of words: Evidence of a dependence between retrieval operations. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1971;90:227–234. doi: 10.1037/h0031564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow DG, Bower GH, Greenspan SL. Updating situation models during narrative comprehension. Journal of Memory and Language. 1989;28:292–312. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow DG, Greenspan SL, Bower GH. Accessibility and situation models in narrative comprehension. Journal of Memory and Language. 1987;28:165–187. [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien EJ, Shank DM, Myers JL, Rayner K. Elaborative inferences during reading: Do they occur online? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1988;14:410–420. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.14.3.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts GR, Keenan JM, Golding JM. Assessing the occurrence of elaborative inferences: Lexical decision versus naming. Journal of Memory and Language. 1988;27:399–415. [Google Scholar]

- Schank RC, Abelson RP. Scripts, plans, goals and understanding. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Seidenberg MS, Waters GS, Sanders M, Langer P. Pre- and post-lexical loci of contextual effects on word recognition. Memory & Cognition. 1984;12:315–328. doi: 10.3758/bf03198291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson GB, Burgess C. Activation and selection processes in the recognition of ambiguous words. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1985;11:28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Singer M. Processes of inference in sentence encoding. Memory & Cognition. 1979;7:192–200. [Google Scholar]

- Singer M. The role of case-filling inferences in the coherence of brief passages. Discourse Processes. 1980;3:185–200. [Google Scholar]

- Singer M, Ferreira F. Inferring consequences in story comprehension. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 1983;22:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Tweedy JR, Lapinsky RH, Schvaneveldt RW. Semantic-context effects on word recognition: Influence of varying the proposition of items presented in an appropriate context. Memory & Cognition. 1977;5:84–89. doi: 10.3758/BF03209197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]