Abstract

Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus) is one of the most important freshwater fish that is native to China, and crisp grass carp is a kind of high value-added fishes which have higher muscle firmness. To investigate biological functions and possible signal transduction pathways that address muscle firmness increase of crisp grass carp, microarray analysis of 14,900 transcripts was performed. Compared with grass carp, 127 genes were upregulated and 114 genes were downregulated in crisp grass carp. Gene ontology (GO) analysis revealed 30 GOs of differentially expressed genes in crisp grass carp. And strong correlation with muscle firmness increase of crisp grass carp was found for these genes from differentiation of muscle fibers and deposition of ECM, and also glycolysis/gluconeogenesis pathway and calcium metabolism may contribute to muscle firmness increase. In addition, a number of genes with unknown functions may be related to muscle firmness, and these genes are still further explored. Overall, these results had been demonstrated to play important roles in clarifying the molecular mechanism of muscle firmness increase in crisp grass carp.

1. Introduction

Freshwater aquaculture plays a very significant role in global aquaculture production. In 2011, 56.8% of the global aquaculture production was freshwater fishes, and output amounted to 35.6 million tons [1]. Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus) is one of the most important freshwater fish that is native to China, and it plays an important role in aquaculture with 4.57 million tons produced in 2011, the highest in fish production worldwide [1]. In China, the grass carp industry aims to increase the production of value-added products in order to improve profitability [2], and crisp grass carp is a kind of high value-added fishes which have firmer muscle and higher contents of crude protein, fat, and amino acids than grass carp [3–5]. Currently in Guangdong province of China, the crisp grass carp has become an economically important freshwater fish because of its increased muscle firmness (hardness).

Fillet firmness of fish is an important quality trait for consumer acceptance in many studies with Chinook and Atlantic salmon [6, 7], channel catfish [8], and gilthead sea bream [9]. Muscle firmness is associated with the intrinsic structure and properties of components of the flesh. It has been found in many studies that firmness is influenced by muscle fiber density, muscle fiber diameter, and intermyofibrillary spaces and gaps [10–13]. These factors are determined by changes in the cellularity of skeletal muscle [14, 15]. The changes in cellularity will contribute to changes in the quality of the skeletal muscle, and since this tissue is the part of the fish destined for human consumption, it may have important economic value [16].

Sole faba bean (Vicia faba) feeding differentially enhances muscle firmness of grass carp and the grass carp with higher muscle firmness is called crisp grass carp [17]. Although the composition of faba bean is complex, common characteristic of muscle firmness increase is also demonstrated in other fishes feeding on faba bean including European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax) [18, 19] and channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) [20]. In the previous studies of crisp grass carp muscle, it has been found that the diameter of muscle fibers was decreased and the content of the ECM was increased [2, 4, 17], and our team also found that the increase in the expression of type I collagen in crisp grass carp is higher than those of grass carp [5]. However, the regulatory mechanism of muscle firmness increase in crisp grass carp is still unclear. Given that the expression of muscle firmness increase was regulated by multiple genes network [21], it is expedient to analyze systematically muscle firmness increase of crisp grass carp in the gene levels using microarray technology, which may help to explore signal transduction pathways of nutritional regulation of fish muscle firmness.

Microarray technology presents a powerful tool for revealing expression patterns and genes associated with phenotypic characteristics [22]. By determination of expression levels of thousands of genes simultaneously in muscle tissue, it could be effective to reveal global gene expression patterns and to identify genes or groups of genes associated with texture variations of Atlantic salmon [21]. In this study, crisp grass carp, having higher muscle firmness, is used to characterize the global gene expression profile in the muscle in comparison with that of grass carp and analyze the biological functions and possible signal transduction pathways that address muscle firmness of crisp grass carp.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fish

The grass carp and crisp grass carp are raised in six enclosures in the Dongsheng Aquatic Breeding Base (Zhongshan, Guangdong, China), and the diet of grass carp is artificial feed and the diet of crisp grass carp is sole faba bean (Vicia faba). The average weights of the specimens were 3.98 ± 0.36 kg (n = 60) for crisp grass carp and 3.45 ± 0.52 kg (n = 60) for grass carp. In this paper, living fishes were directly dissected and the white muscle tissues of three fishes were obtained for crisp grass carp and grass carp, respectively. The obtained samples were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for RNA extraction.

2.2. RNA Preparation

Total RNA was isolated from white muscle using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instruction. The concentration of the isolated RNA was determined by measuring absorbance at 260 nm. The integrity of the RNA was determined by agarose gel electrophoresis and Agilent BioAnalyzer 2100. The RNA was used for microarray analysis and quantitative real-time PCR confirmation.

2.3. Microarray, cDNA Labeling, Hybridization, Scanning, and Data Analysis

Affymetrix zebrafish chip containing oligonucleotides representing 14,900 transcripts was used to profile the differences in genes expression of the muscles between crisp grass carp and grass carp. Microarray chips (AFFY-900487) were obtained from Shanghaibio (Shanghai, China). Gene expression levels were determined by comparing the amount of mRNA transcript present in the experimental sample to the control. All experiments were performed following the protocol of Affymetrix Inc. RNA samples of each group were used to generate biotinylated cRNA targets. Hybridizations were performed in the Fluidics Station 450 and chips were scanned using the Affymetrix Scanner 3000. Fluorescent signal intensities for all spots on the arrays were analyzed using the Gene Chip Operating System (GCOS; Affymetrix). Following preprocessing, the data were normalized using global LOWESS normalization. Microarray data were deposited (according to Microarray Gene Expression Data Society Standards) in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) with the series accession number (GSE4787).

2.4. GO Category and Pathway Analysis

The categorization of biological process GO (gene ontology) was analyzed using DAVID Bioinformatics Resources 6.7 (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/). Within the significant category, the enrichment Re was given by Re = (n f/n)/(N f/N), where n f was the number of differential genes within the particular category, n was the total number of genes in the same category, N f was the number of differential genes in the entire microarray, and N was the total number of genes in the microarray. The pathway analysis was conducted using KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) database. The false discovery rate (FDR) was calculated to correct the P value. P value < 0.05 and FDR < 0.05 were used as the threshold to select significant GO categories and KEGG pathways.

2.5. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

To validate microarray data, the expression levels of six genes of interest were quantified using real-time PCR with β-actin as the internal control. These genes included myostatin (MSTN), collagen type I alpha-1 (COL1A1), collagen type I alpha-2 (COL1A2), and calreticulin (CALR), heat shock cognate 70-kd protein (HSP70), and heat shock protein 90 kDa alpha (HSP90) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Primers used in quantitative real-time PCR.

| Gene name | Forward primer (5′→3′) | Reverse primer (5′→3′) | GenBank accession number |

|---|---|---|---|

| HSP70 | GTGTGAGCGAGCCAAGAGAA | TTGTTGATCCACCAACCAGAA | FJ483832 |

| HSP90 | GCCGTGGAACCAGAGTCATT | ATCTCCTTGTCGCGTTCCTT | FJ517554 |

| MSTN | TGCCACCACAGAGACCATCA | TGTGTCTTCCTCCGTCCGTAA | EU555520 |

| COL1A1 | GCATGGGGCAAGACAGTCA | ACGCACACAAACAATCTCAAGT | HM363526.1 |

| COL1A2 | ACATTGGTGGCGCAGATCA | ACTCCGATAGAGCCCAGCTT | HM771241.1 |

| CALR | AGGCAGAACCACCTAATCAA | CCACCTTCTCGTTGTCGATTT | HQ444741.1 |

| β-Actin | TGACGAGGCTCAGAGCAAGA | GCAACACGCAGCTCGTTGTA | M25013 |

The cDNA synthesis was performed using 0.5 μg of DNase-treated total RNA (Turbo DNA-free; Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) using TaqMan Gold Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and oligo-dT primers. PCR primers (Table 1) were designed using Vector NTI and synthesized by Invitrogen. The amplicon lengths were checked on 1% agarose gel. PCR efficiency was calculated from tenfold serial dilutions of cDNA for each primer pair in triplicate. Real-time PCR assays were conducted using FastStart SYBR Green Master (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) in an optimized 12 μL reaction volume, using 1 : 10 diluted cDNA, with primer concentrations of 0.4–0.6 μM. PCR was performed in duplicate in 96-well optical plates on Light Cycler 480 (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) under the following conditions: 95°C for 5 min (preincubation), 95°C for 5 s, 60°C for 15 s, 72°C for 15 s (amplification), 95°C for 5 s, and 65°C for 1 min (melting curve). 45 cycles were performed. Relative expression of mRNA was evaluated using the ΔΔCT method. Statistical differences were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Duncan's multiple range test (P < 0.05). All statistics were performed using software SPSS 15.0.

3. Results

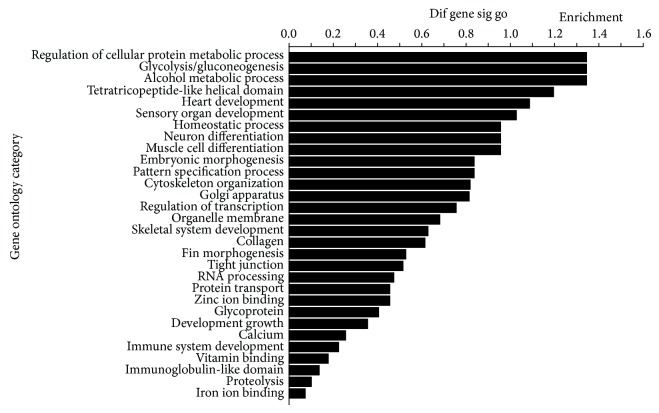

The microarray analysis demonstrated that expressions of 127 genes were upregulated and 114 genes were downregulated in the muscle of crisp grass carp compared with the control group. According to the genes of differential expression, the biological processes GO terms mainly consisted of protein metabolism, muscle development and growth, carbohydrate metabolism, and so on (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

GO category based on biological process for differentially expressed genes. Vertical axis was the GO category and horizontal axis was the enrichment of GO.

3.1. Genes Involved in Protein Metabolism

Differentially expressed genes involved in protein metabolism in the muscle of crisp grass carp and grass carp were shown in Table 2. Expressions of collagen type I alpha-1 and alpha-2, type II alpha-1a were upregulated in the muscle of crisp grass carp. Differentially expressed genes involved in the protein metabolism were clustered into biological categories including protein transport (9 genes), proteolysis (9 genes), and regulation of cellular protein metabolic process (4 genes). The 11 genes that regulate the glycoproteins were found with nine notably upregulated and two downregulated.

Table 2.

Differentially expressed genes involved in protein metabolism in the muscle of crisp grass carp and grass carp.

| Gene name | Affy-ID | Fold change |

|---|---|---|

| Collagen | ||

| Collagen, type I, alpha-2 | DrAffx.2.1.S1_s_at | 5.049230 |

| Collagen, type I, alpha-1 | Dr.1377.1.A1_at | 4.646780 |

| Collagen type II, alpha-1a | Dr.3761.1.S1_at | 4.283097 |

| si:ch211-106n13.3 | Dr.1276.1.A1_at | 1.825742 |

| Procollagen-proline, 2-oxoglutarate 4-dioxygenase (proline 4-hydroxylase), alpha polypeptide-2; hypothetical protein LOC100151456 |

Dr.19144.1.A1_at | 0.253430 |

| C1q and tumor necrosis factor related protein-5 | Dr.965.1.S1_at | 0.212245 |

| Proteolysis | ||

| Ubiquitin specific protease-16 | Dr.21873.1.A1_at | 4.844206 |

| Phosphate regulating gene with homologues to endopeptidases on the X chromosome | Dr.25529.1.S1_at | 1.544958 |

| Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2E 3 (UBC4/5 homolog, yeast) | Dr.23793.1.A1_at | 0.581777 |

| zgc:123295 | Dr.18631.1.S1_at | 0.502692 |

| zgc:92791; hypothetical LOC797742 | Dr.15777.1.A1_at | 0.396054 |

| Carboxypeptidase-A5 | Dr.4882.1.S1_at | 0.333607 |

| Speckle-type POZ protein | Dr.12893.1.S1_at | 0.202174 |

| Six-cysteine containing astacin protease 1 | Dr.21939.1.A1_at | 0.201674 |

| Janus kinase-1 | Dr.18349.1.A1_at | 0.188976 |

| Protein transport | ||

| zgc:92303 | Dr.4306.1.A1_at | 12.18947 |

| zgc:77724 | Dr.14413.1.A1_at | 4.213999 |

| KDEL (Lys-Asp-Glu-Leu) endoplasmic reticulum protein retention receptor 2, like | Dr.1198.1.A1_at | 2.799246 |

| Clathrin, light chain (Lca) | Dr.26380.1.A1_at | 1.98067 |

| Translocase of inner mitochondrial membrane 17 homolog A (yeast) | Dr.3096.1.A1_at | 1.92503 |

| Importin-7 | Dr.19552.1.S1_at | 0.523015 |

| Adaptor-related protein complex 1, sigma 1 subunit | Dr.18735.1.A1_at | 0.409458 |

| Similar to peroxisome biogenesis factor 13; peroxisome biogenesis factor 13 | Dr.6902.1.S1_at | 0.321697 |

| Chromatin modifying protein 4B | Dr.16859.1.S1_at | 0.274372 |

| Regulation of cellular protein metabolic process | ||

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor-5A | Dr.20010.3.S2_at | 3.296618 |

| Neuroguidin, EIF4E binding protein | Dr.20137.1.S1_at | 2.291049 |

| Axin 1 | Dr.17733.1.S1_at | 0.505078 |

| MAP kinase-interacting serine/threonine kinase 2b | Dr.17570.1.S3_at | 0.449659 |

| Glycoprotein | ||

| Rhesus blood group, B glycoprotein | Dr.9532.1.S1_at | 8.115116 |

| Stromal cell-derived factor-4 | Dr.20092.1.S1_at | 4.935459 |

| Acetylcholinesterase | Dr.15722.1.S1_at | 4.445239 |

| Melatonin receptor type 1B a | Dr.20978.1.S1_at | 3.767983 |

| Semaphorin 3ab | Dr.8112.1.S1_at | 3.37293 |

| Myelocytomatosis oncogene b | Dr.16048.1.S1_at | 3.10492 |

| zgc:123242 | Dr.13408.1.S1_at | 2.546485 |

| Ephrin-A2 | Dr.20957.2.A1_at | 1.785163 |

| Fibroblast growth factor receptor-4 | Dr.409.1.S1_at | 1.746774 |

| Opsin 1 (cone pigments), long-wave-sensitive, 1 | Dr.131175-1_s_at | 0.379971 |

| Transmembrane protein-192 | Dr.17388.2.S1_at | 0.214102 |

Fold change = (signal intensity of a gene in the muscle of crisp grass carp)/(signal intensity of the gene in the muscle of grass carp).

3.2. Genes Involved in Muscle Development and Growth

The genes involved in muscle development and growth were classified into developmental growth (4 genes), muscle cell differentiation (4 genes), skeletal system development (4 genes), and cytoskeleton organization (14 genes) in the crisp grass carp. Above all, transcription of MSTN, which was tightly related to muscle development, was upregulated in the muscle of crisp grass carp (Table 3). In addition, the mRNAs of three genes responsible for tight junction were upregulated.

Table 3.

Differentially expressed genes involved in muscle development and growth in the muscle of crisp grass carp and grass carp.

| Gene name | Affy-ID | Fold change |

|---|---|---|

| Developmental growth | ||

| Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 12a (stromal cell-derived factor-1) | Dr.822.1.S3_at | 3.862025 |

| Myostatin (MSTN) | Dr.5778.1.S1_at | 3.411231 |

| Axin 1 | Dr.17733.1.S1_at | 0.505078 |

| Survival of motor neuron protein interacting protein-1 | Dr.2724.1.S1_at | 0.480291 |

| Muscle cell differentiation | ||

| Acetylcholinesterase | Dr.15722.1.S1_at | 4.445239 |

| Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 12a (stromal cell-derived factor 1) | Dr.822.1.S3_at | 3.862025 |

| Glycogen synthase kinase 3-alpha | Dr.259.1.S1_at | 0.663178 |

| Pre-B-cell leukemia transcription factor-1a; zgc:1588-24; pre-B-cell leukemia transcription factor-4; hypothetical LOC100004634; hypothetical protein LOC100150879 |

Dr.4926.1.S1_at | 0.175405 |

| Cytoskeleton organization | ||

| Acetylcholinesterase | Dr.15722.1.S1_at | 4.445239 |

| Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 12a (stromal cell-derived factor 1) | Dr.822.1.S3_at | 3.862025 |

| zgc:158673 | Dr.4838.1.A1_at | 2.108265 |

| Capping protein (actin filament) muscle Z-line, beta | Dr.25474.1.S1_at | 1.611818 |

| Tubulin, beta-2c | Dr.5605.3.S1_x_at | 0.566588 |

| Actin related protein 2/3 complex, subunit 4, like; actin related protein 2/3 complex, subunit 4 | Dr.5314.1.S1_at | 0.459813 |

| Septin-8a | Dr.4204.1.A1_at | 0.388101 |

| Similar to RP11-100C15.2 | Dr.21663.1.A1_at | 0.284452 |

| Lamin-B1 | Dr.25051.1.S2_at | 0.249782 |

| ADP-ribosylation factor-like 8-Ba | Dr.7615.1.A1_at | 0.249671 |

| zgc:136930 | Dr.24487.1.A1_at | 0.233076 |

| Hypothetical protein LOC553488 | Dr.26067.1.A1_s_at | 0.221494 |

| Janus kinase-1 | Dr.18349.1.A1_at | 0.188970 |

| Nexilin (F actin binding protein) | Dr.4859.1.A1_at | 0.139300 |

| Skeletal system development | ||

| Activin A receptor, type I like | Dr.606.1.S2_at | 11.01876 |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor-3, subunit E, a/b | Dr.5119.1.A1_at | 4.241705 |

| Cytochrome P-450, family-26, subfamily b, polypeptide 1 | Dr.180.1.A1_at | 3.092533 |

| Runt-related transcription factor-3 | Dr.10668.1.S2_at | 0.174100 |

| Tight junction | ||

| zgc:110333; zgc:173444 | Dr.10400.1.A1_at | 3.965793 |

| Tight junction protein-3 | Dr.21038.1.S1_at | 3.436695 |

| Occludin-alpha | Dr.7692.1.A1_at | 2.112512 |

Fold change = (signal intensity of a gene in the muscle of crisp grass carp)/(signal intensity of the gene in the muscle of grass carp).

3.3. Genes Involved in Carbohydrate Metabolism

Downregulated expressions of glycolytic enzymes were detected in the muscle of crisp grass carp (Table 4). These enzymes include enolase-3, hexokinase-1, hexokinase-2, phosphofructokinase, pyruvate dehydrogenase, glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase and phosphatase, and tensin homolog-B.

Table 4.

Differentially expressed genes involved in carbohydrate metabolism in the muscle of crisp grass carp and grass carp.

| Gene name | Affy-ID | Fold change |

|---|---|---|

| Glycolysis/gluconeogenesis | ||

| Aldehyde dehydrogenase-3 family, member D1 | Dr.4094.1.S1_at | 5.510521 |

| T-box 24 | Dr.18309.1.S1_at | 5.279783 |

| zgc:55970 | Dr.24685.1.S1_at | 1.887322 |

| Hexokinase-2 | Dr.10553.1.S1_at | 1.760913 |

| Enolase-3 (beta, muscle) | Dr.9746.4.S1_at | 0.640655 |

| Phosphofructokinase, muscle a | Dr.13621.1.A1_at | 0.615103 |

| Cytochrome c oxidase, subunit VIIc | Dr.7444.1.S1_at | 0.380282 |

| Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 | Dr.20553.2.A1_at | 0.223735 |

| Pyruvate dehydrogenase (lipoamide) alpha-1a | Dr.2656.1.A1_at | 0.152896 |

| hexokinase-1 | Dr.25364.1.A1_s_at | 0.121231 |

| Alcohol metabolic process | ||

| Acetylcholinesterase | Dr.15722.1.S1_at | 4.445239 |

| Hexokinase-2 | Dr.10553.1.S1_at | 1.760913 |

| Phosphofructokinase, muscle a | Dr.13621.1.A1_at | 0.645103 |

| Enolase-3 (beta, muscle) | Dr.9746.4.S1_at | 0.600655 |

| Glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase domain containing-3 | Dr.10416.1.S1_at | 0.274577 |

| Phosphatase and tensin homolog B (mutated in multiple advanced cancers 1) | Dr.5559.3.A1_at | 0.195537 |

| Pyruvate dehydrogenase (lipoamide) alpha 1a | Dr.2656.1.A1_at | 0.152896 |

| Hexokinase-1 | Dr.25364.1.A1_s_at | 0.121231 |

Fold change = (signal intensity of a gene in the muscle of crisp grass carp)/(signal intensity of the gene in the muscle of grass carp).

3.4. Genes Involved in Calcium and Other Ions' Metabolism

In the muscle of crisp grass carp, fifty-five differentially expressed genes related to metal ions were detected. The GOs of these genes included zinc ion binding, calcium and iron ion binding (Table 5). As genes involved in vitamin metabolism, cysteine conjugate-beta lyase and KATIII were upregulated.

Table 5.

Differentially expressed genes involved in metal ions and vitamin metabolism in the muscle of crisp grass carp and grass carp.

| Gene name | Affy-ID | Fold change |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium | ||

| Rhomboid, veinlet-like 3 (Drosophila); hypothetical LOC100005244 | Dr.25770.2.A1_at | 6.680544 |

| Stromal cell-derived factor-4 | Dr.20092.1.S1_at | 4.935459 |

| Protocadherin-10a | Dr.21790.1.A1_at | 4.905736 |

| Calreticulin | Dr.25177.1.S1_at | 3.450125 |

| zgc:123242 | Dr.13408.1.S1_at | 2.546485 |

| Parvalbumin-3 | Dr.15359.1.S1_at | 1.997458 |

| Calmodulin 2b, /// calmodulin 3b /// calmodulin 3a /// calmodulin 2a /// calmodulin 1b /// zgc:55813 /// calmodulin 1a |

Dr.7638.1.S1_at | 1.549420 |

| zgc:136759 | Dr.19975.1.S1_at | 0.336455 |

| Guanylate cyclase activator 1-A | Dr.12592.1.S1_at | 0.30074 |

| Desmocollin 2-like | Dr.934.1.A1_at | 0.23301 |

| Iron ion binding | ||

| zgc:92245; hypothetical LOC792323 | Dr.20662.1.A1_at | 4.470659 |

| Transferrin-a; Rho-class glutathione S-transferase | Dr.1889.1.S1_at | 3.685072 |

| Cytochrome P450, family 26, subfamily b, polypeptide-1 | Dr.180.1.A1_at | 3.092533 |

| Cytochrome c oxidase, subunit VIIc | Dr.7444.1.S1_at | 2.380282 |

| Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 | Dr.20553.2.A1_at | 2.223735 |

| Procollagen-proline, 2-oxoglutarate 4-dioxygenase (proline 4-hydroxylase), alpha polypeptide 2; hypothetical protein LOC100151456 |

Dr.19144.1.A1_at | 0.25343 |

| Zinc ion binding | ||

| Similar to zinc finger protein-135 (zinc finger protein 61) (zinc finger protein 78-like 1); zgc:174288; zgc:110249 |

Dr.11066.2.A1_a_at | 13.94189 |

| si:ch211-222k6.1; si:ch211-222k6.2; zgc:174564 | Dr.23520.1.A1_at | 12.04316 |

| Similar to COASTER | Dr.14346.2.A1_x_at | 11.16127 |

| zgc:174263 | Dr.15456.1.A1_at | 6.072371 |

| Muscleblind-like (Drosophila); hypothetical protein LOC100150760; hypothetical protein LOC100150761 |

Dr.25973.1.A1_at | 6.004707 |

| Ubiquitin specific protease-16 | Dr.21873.1.A1_at | 4.844206 |

| si:rp71-15k1.2; myeloid/lymphoid or mixed-lineage leukemia-4a | Dr.9377.1.A1_at | 4.679487 |

| si:ch211-45m15.2 | Dr.8200.1.S1_at | 4.653204 |

| zic family member-2 (odd-paired homolog, Drosophila) b | Dr.10614.1.A1_at | 4.526444 |

| zgc:77724 | Dr.14413.1.A1_at | 4.213999 |

| zgc:162730 | Dr.3936.1.A1_at | 3.742291 |

| RNA binding motif protein 4.1 | Dr.21594.1.A1_at | 3.487187 |

| l(3)mbt-like 2 (Drosophila) | Dr.17271.1.A1_at | 3.197401 |

| LIM and SH3 protein-1 | Dr.25320.1.A1_at | 2.882738 |

| LIM and calponin homology domains-1 | Dr.10986.1.A1_at | 2.689072 |

| zgc:158673 | Dr.4838.1.A1_at | 2.108265 |

| si:ch73-38p6.1 | Dr.3142.1.S1_at | 1.823564 |

| zgc:56116 | Dr.745.1.A1_at | 1.590587 |

| Phosphate regulating gene with homologues to endopeptidases on the X chromosome | Dr.25529.1.S1_at | 1.544958 |

| Zinc finger protein-207, a | Dr.93.1.A1_a_at | 0.65725 |

| Retinoic acid receptor, alpha b | Dr.305.1.S1_at | 0.566773 |

| Alpha thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome X-linked, like; alpha thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome X-linked homolog (human) |

Dr.26404.2.S1_at | 0.502432 |

| APC11 anaphase promoting complex subunit 11 homolog | Dr.18189.1.S1_at | 0.491208 |

| zgc:174649; similar to zinc finger protein-180 (HHZ168); hypothetical LOC570013; zgc:174651; similar to zinc finger protein-560; zgc:173603 |

Dr.21894.1.A1_at | 0.474262 |

| zgc:56628 | Dr.18443.1.S1_at | 0.462863 |

| Carboxypeptidase-A5 | Dr.4882.1.S1_at | 0.333607 |

| zgc:153061 | Dr.6513.1.A1_a_at | 0.323466 |

| zgc:153171; F-box only protein 11-like | Dr.12361.1.S1_at | 0.308205 |

| wu:fi20g04 | Dr.7293.1.S1_at | 0.262579 |

| Novel protein similar to human rearranged L-myc fusion sequence (RLF) | Dr.15042.1.A1_at | 0.256942 |

| si:dkeyp-89d7.1 | Dr.4953.1.S1_at | 0.236327 |

| Zinc finger, FYVE domain containing 21 | Dr.3023.1.S1_at | 0.216677 |

| wu:fd12d03 | Dr.2692.1.A1_at | 0.210638 |

| Six-cysteine containing astacin protease-1 | Dr.21939.1.A1_at | 0.201674 |

| Janus kinase-1 | Dr.18349.1.A1_at | 0.188976 |

| zgc:158455 | Dr.15141.1.A1_at | 0.184993 |

| LIM homeobox-1a | Dr.24443.1.A1_at | 0.182767 |

| Zinc fingers and homeoboxes 3 | Dr.26180.1.A1_at | 0.150721 |

| Transcription elongation factor A (SII), 3 | Dr.15634.1.S1_at | 0.093517 |

| Vitamin binding | ||

| Cysteine conjugate-beta lyase; cytoplasmic (glutamine transaminase K, kynurenine aminotransferase) |

Dr.2828.2.A1_at | 9.133776 |

| Similar to Kynurenine-oxoglutarate transaminase-3 (Kynurenine-oxoglutarate transaminase III) (Kynurenine aminotransferase III) (KATIII) (cysteine-S-conjugate beta-lyase 2); cysteine conjugate-beta lyase-2 |

Dr.18800.1.S1_at | 1.518084 |

| Procollagen-proline, 2-oxoglutarate 4-dioxygenase, alpha polypeptide 2; hypothetical protein LOC100151456 |

Dr.19144.1.A1_at | 0.25343 |

Fold change = (signal intensity of a gene in the muscle of crisp grass carp)/(signal intensity of the gene in the muscle of grass carp).

3.5. Genes Involved in Nucleic Acid Metabolism

The differential expression of genes involved in protein biosynthesis occurred at multiple levels, including regulation of transcription (31 genes), RNA processing (6 genes), and tetratricopeptide-like helical domain (8 genes) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Differentially expressed genes involved in nucleic acid metabolism in the muscle of crisp grass carp and grass carp.

| Gene name | Affy-ID | Fold change |

|---|---|---|

| Regulation of transcription | ||

| T-box 24 | Dr.18309.1.S1_at | 5.279783 |

| Ubiquitin specific protease-16 | Dr.21873.1.A1_at | 4.844206 |

| si:ch211-45m15.2 | Dr.8200.1.S1_at | 4.653204 |

| Neurogenin-1 | Dr.555.1.S1_at | 4.347208 |

| zgc:152921 | Dr.21248.1.A1_at | 3.604867 |

| l(3)mbt-like 2 (Drosophila) | Dr.17271.1.A1_at | 3.197401 |

| Myelocytomatosis oncogene b | Dr.16048.1.S1_at | 3.10492 |

| zgc:92106 | Dr.7710.1.A1_at | 2.86037 |

| E74-like factor 2 (ets domain transcription factor) | Dr.2328.1.S1_at | 2.775788 |

| zgc:153012 | Dr.17420.1.S1_at | 2.482655 |

| TGFB-induced factor homeobox-1 | Dr.139.1.S1_at | 2.45607 |

| Ventral anterior homeobox-1 | DrAffx.1.61.S1_at | 2.194558 |

| Diencephalon/mesencephalon homeobox-1a | Dr.18845.1.S1_at | 2.072013 |

| Homeobox B4a | Dr.15716.1.S1_at | 2.071785 |

| CCR4-NOT transcription complex, subunit 3b | Dr.6354.2.A1_x_at | 1.938399 |

| Telomeric repeat binding factor (NIMA-interacting) 1 | Dr.25530.1.A1_at | 0.662482 |

| Retinoic acid receptor, alpha b | Dr.305.1.S1_at | 0.566773 |

| Activating transcription factor-7 interacting protein | Dr.433.2.S1_at | 0.312221 |

| zgc:162976 | Dr.6862.1.A1_at | 0.278785 |

| si:dkey-211g8.3 | Dr.18812.1.S1_at | 0.256496 |

| Sine oculis-related homeobox-6a | Dr.26486.1.S1_at | 0.243693 |

| Suppressor of Ty 6 homolog (S. cerevisiae) | Dr.6422.1.S1_at | 0.240522 |

| POU domain gene-12 | Dr.37.2.S1_at | 0.230685 |

| wu:fd12d03 | Dr.2692.1.A1_at | 0.210638 |

| Heat shock transcription factor-1 | Dr.8301.1.S1_a_at | 0.193731 |

| Interferon regulatory factor-7 | Dr.10428.1.S1_at | 0.184330 |

| LIM homeobox-1a | Dr.24443.1.A1_at | 0.182767 |

| Pre-B-cell leukemia transcription factor 1a; zgc:158824; pre-B-cell leukemia transcription factor 4; hypothetical LOC100004634; hypothetical protein LOC100150879 |

Dr.4926.1.S1_at | 0.175405 |

| Runt-related transcription factor-3 | Dr.10668.1.S2_at | 0.174100 |

| Zinc fingers and homeoboxes-3 | Dr.26180.1.A1_at | 0.150721 |

| Transcription elongation factor A (SII), 3 | Dr.15634.1.S1_at | 0.093517 |

| RNA processing | ||

| Trinucleotide repeat containing-4 | Dr.8323.1.S1_at | 6.653872 |

| Molybdenum cofactor synthesis-3 | Dr.13391.1.S1_at | 2.424007 |

| PRP39 pre-mRNA processing factor 39 homolog (yeast) | Dr.340.1.S1_at | 1.852201 |

| Survival of motor neuron protein interacting protein-1 | Dr.2724.1.S1_at | 0.480291 |

| XPA binding protein-2 | Dr.12501.1.A1_at | 0.348226 |

| Polypyrimidine tract binding protein-1a | Dr.20803.2.S1_at | 0.166418 |

| Tetratricopeptide-like helical domain | ||

| Tetratricopeptide repeat domain-8 | Dr.11994.1.A1_at | 2.342792 |

| PRP39 pre-mRNA processing factor 39 homolog (yeast) | Dr.340.1.S1_at | 1.852201 |

| Tetratricopeptide repeat domain-5 | Dr.6679.1.A1_at | 0.463885 |

| Sperm associated antigen-1 | Dr.9954.1.A1_at | 0.355814 |

| XPA binding protein-2 | Dr.12501.1.A1_at | 0.348226 |

| FIC domain containing | Dr.13784.1.A1_at | 0.337339 |

| Procollagen-proline, 2-oxoglutarate 4-dioxygenase (proline 4-hydroxylase), alpha polypeptide 2; hypothetical protein LOC100151456 |

Dr.19144.1.A1_at | 0.253430 |

| Protein-kinase, interferon-inducible double stranded RNA dependent inhibitor | Dr.10669.1.S1_at | 0.182015 |

Fold change = (signal intensity of a gene in the muscle of crisp grass carp)/(signal intensity of the gene in the muscle of grass carp).

3.6. Genes of Differential Expression Involved in Other GOs

Fifty-two differentially expressed genes were included in the GO terms of immune system development and immunoglobulin-like domain (13 genes), embryonic morphogenesis (9 genes), Golgi apparatus (6 genes), neuron differentiation (8 genes), organelle membrane (13 genes), and fin morphogenesis (3 genes) (Table 7).

Table 7.

Differentially expressed genes involved in other GOs (gene ontology) in the muscle of crisp grass carp and grass carp.

| Gene name | Affy-ID | Fold change |

|---|---|---|

| Immune system development | ||

| Activin A receptor, type I like | Dr.606.1.S2_at | 11.01876 |

| Heat shock cognate 70-kd protein | NM_131397.2 | 3.284166 |

| SNF related kinase-1 | Dr.25951.1.A1_at | 3.016243 |

| Heat shock protein 90 kDa alpha, cytosolic, B1 | NM_131310.1 | 0.302405 |

| runt-related transcription factor-3 | Dr.10668.1.S2_at | 0.174100 |

| Immunoglobulin-like domain | ||

| Major histocompatibility complex class I UDA gene | Dr.22347.1.S1_at | 11.02728 |

| Neural cell adhesion molecule-2 | Dr.12598.1.S1_at | 5.365372 |

| Semaphorin-3ab | Dr.8112.1.S1_at | 3.37293 |

| Fibroblast growth factor receptor-4 | Dr.409.1.S1_at | 1.746774 |

| Junctional adhesion molecule-3 | Dr.4725.1.A1_at | 0.618889 |

| Basigin | Dr.16700.1.A1_at | 0.305291 |

| Nexilin (F actin binding protein) | Dr.4859.1.A1_at | 0.139300 |

| zgc:171897 | Dr.21314.1.A1_at | 0.116185 |

| Embryonic morphogenesis | ||

| Activin A receptor, type I like | Dr.606.1.S2_at | 11.018760 |

| traf and tnf receptor associated protein | Dr.18071.2.A1_at | 4.529896 |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3, subunit E, b; eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3, subunit E, a |

Dr.5119.1.A1_at | 4.241705 |

| Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand-12a (stromal cell-derived factor 1) | Dr.822.1.S3_at | 3.862025 |

| Cytochrome P-450, family-26, subfamily b, polypeptide 1 | Dr.180.1.A1_at | 3.092533 |

| One-eyed pinhead | Dr.581.1.S1_at | 2.272094 |

| Similar to frizzled homolog 7b; frizzled homolog 7b; frizzled homolog 7a | Dr.5454.1.S1_at | 2.128164 |

| Axin-1 | Dr.17733.1.S1_at | 0.505078 |

| Pre-B-cell leukemia transcription factor 1a; zgc:158824; pre-B-cell leukemia transcription factor 4; hypothetical LOC100004634; hypothetical protein LOC100150879 |

Dr.4926.1.S1_at | 0.175405 |

| Fin morphogenesis | ||

| Activin A receptor, type I like | Dr.606.1.S2_at | 11.01876 |

| Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 12a (stromal cell-derived factor 1) | Dr.822.1.S3_at | 3.862025 |

| Axin-1 | Dr.17733.1.S1_at | 0.505078 |

| Golgi apparatus | ||

| Stromal cell-derived factor-4 | Dr.20092.1.S1_at | 4.935459 |

| Clathrin, light chain (Lca) | Dr.26380.1.A1_at | 1.980670 |

| UDP-Gal:betaGlcNAc beta 1,3-galactosyltransferase, polypeptide 2 | Dr.11084.1.A1_at | 1.701953 |

| Partial optokinetic response-b | Dr.9437.1.A1_at | 1.616283 |

| Adaptor-related protein complex 1, sigma 1 subunit | Dr.18735.1.A1_at | 0.409458 |

| Beta-3-galactosyltransferase | DrAffx.1.31.S1_at | 0.239189 |

| Neuron differentiation | ||

| T-box 24 | Dr.18309.1.S1_at | 5.279783 |

| Acetylcholinesterase | Dr.15722.1.S1_at | 4.445239 |

| Neurogenin 1 | Dr.555.1.S1_at | 4.347208 |

| Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 12a (stromal cell-derived factor 1) | Dr.822.1.S3_at | 3.862025 |

| Semaphorin 3ab | Dr.8112.1.S1_at | 3.372930 |

| N-Ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor | Dr.9155.1.S1_at | 0.541262 |

| Survival of motor neuron protein interacting protein 1 | Dr.2724.1.S1_at | 0.480291 |

| Pre-B-cell leukemia transcription factor 1a; zgc:158824; pre-B-cell leukemia transcription factor-4; hypothetical LOC100004634; hypothetical protein LOC100150879 |

Dr.4926.1.S1_at | 0.175405 |

| Organelle membrane | ||

| Mitofusin-1 | Dr.14642.1.S1_at | 7.021206 |

| Dullard homolog | Dr.7581.1.A1_at | 5.367876 |

| Translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane-40 homolog, like | Dr.15545.1.A1_at | 4.868413 |

| Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 | Dr.20553.2.A1_at | 2.223735 |

| Clathrin, light chain (Lca) | Dr.26380.1.A1_at | 1.980670 |

| Translocase of inner mitochondrial membrane-17 homolog A (yeast) | Dr.3096.1.A1_at | 1.925030 |

| 6.8 kDa mitochondrial proteolipid-like | Dr.1429.1.S1_at | 1.575235 |

| zgc:86898 | Dr.661.1.S1_at | 0.496350 |

| Adaptor-related protein complex 1, sigma 1 subunit | Dr.18735.1.A1_at | 0.409458 |

| Carnitine palmitoyltransferase II | Dr.146.1.A1_at | 0.308770 |

| zgc:112986 | Dr.20668.1.A1_at | 0.307912 |

| ADP-ribosylation factor-like 8Ba | Dr.7615.1.A1_at | 0.249671 |

| Asparagine-linked glycosylation 6 homolog (S. cerevisiae, alpha-1,3-glucosyltransferase) | Dr.9628.1.A1_at | 0.199667 |

Fold change = (signal intensity of a gene in the muscle of crisp grass carp)/(signal intensity of the gene in the muscle of grass carp).

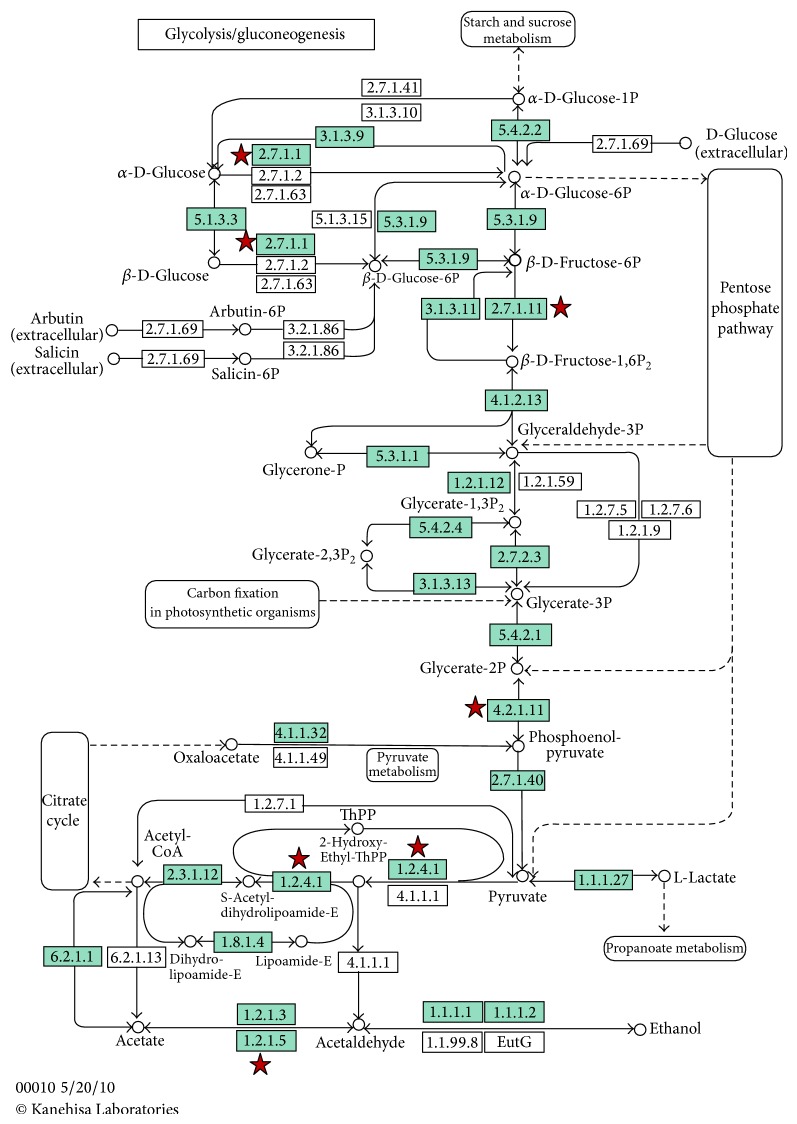

3.7. Pathway Analysis

To further analyze the interactional relation of all differentially expressed genes, the KEGG pathway analysis was used in this study. The results of pathway analysis found that downregulated signals in glycolysis/gluconeogenesis pathway happened in the crisp grass carp (P value < 0.01). The detailed information of glycolysis/gluconeogenesis pathway was shown in Figure 2, which was formed from all differentially expressed genes.

Figure 2.

Pathway information of glycolysis/gluconeogenesis. Green boxes denote signaling pathway protein. Red stars mark the genes of differential expression including upregulated and downregulated genes: box 2.7.1.1 for hexokinase-1 and hexokinase-2, box 2.7.1.11 for phosphofructokinase (muscle a), box 4.2.1.11 for enolase-3 (beta, muscle), box 1.2.4.1 for pyruvate dehydrogenase (lipoamide) alpha-1a, and box 1.2.1.5 for aldehyde dehydrogenase-3 family (member D1). Figure 2 was formed from all differentially expressed genes that were analysed using DAVID Bioinformatics Resources 6.7 (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/).

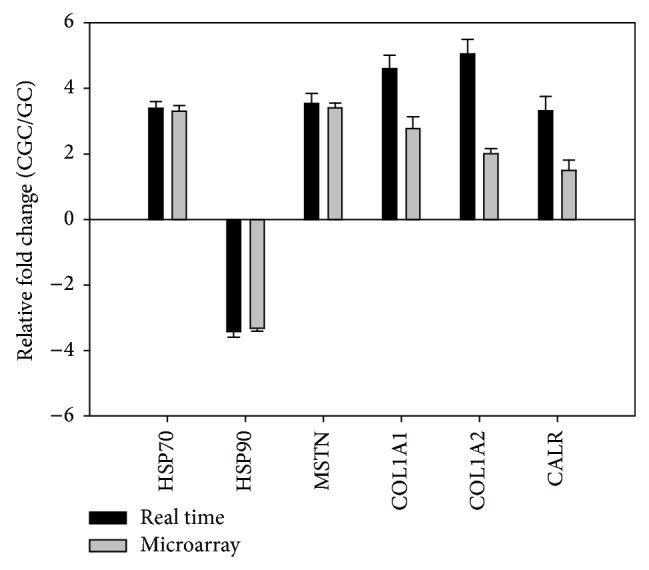

3.8. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

To verify the data obtained by microarray analysis, quantitative real-time PCR was performed for six genes, including five upregulated genes and one downregulated gene, with a β-actin gene used as an internal control. The relative hybridization intensities of the six selected genes are basically consistent with those analyzed by real-time PCR, thus confirming that use of the zebrafish genome array was suitable for this study (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Quantitative real-time PCR confirmation of six differentially expressed genes identified by microarray analysis in crisp grass carp (CGC) versus grass carp (GC). Three samples were used for quantitative real-time PCR confirmation for experimental group and control group. β-Actin gene was used as an internal control. HSP70 for heat shock cognate 70-kd protein, HSP90 for heat shock protein 90 kDa alpha (cytosolic, B1), MSTN for myostatin, COL1A1 for type I collagen (alpha-1), COL1A2 for type I collagen (alpha-2), and CALR for calreticulin. Differential expression was determined by one-way ANOVA (P < 0.05).

4. Discussion

In this study, we show that muscle firmness increase of crisp grass carp is tightly related to the genes of differential expression in the functional groups including differentiation of muscle fibers, deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM), glycolysis/gluconeogenesis pathway, and calcium metabolism.

4.1. Genes Involved in Differentiation of Muscle Fibers

The decrease in the diameter of muscle fibers in crisp grass carp may be related to the downregulated expressions of MSTN and axin and differentially expressed genes involved in diminution of actin filaments. MSTN, known as growth differentiation factor (GDF)-8, was reported to inhibit the proliferation and differentiation of resident muscle cell [23]. In this study, evidence that the growth of muscle cell is inhibited in the muscle of crisp grass carp is that, in the muscle of crisp grass carp, the transcription level of MSTN is elevated from microarray expression, and the mRNA expression of MSTN is 3.4 times that of grass carp by gene quantitative analysis. It was found that the muscle fibres of crisp grass carp were less than those of grass carp [17]. As it is an important protein constituting muscle, diminution of actin filaments in crisp grass carp muscle has been suggested by the differential expressions of genes related to actin. The downregulation of actin related protein 2/3 complex and nexilin and upregulation of capping protein in this paper suggested the diminution of the actin filaments in crisp grass carp muscle [24, 25].

4.2. Genes Involved in Deposition of ECM

In our experiments, muscle firmness increase of the crisp grass carp has been demonstrated in the increasing deposition of ECM, which includes upregulated expressions of collagen and differential expressions of transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), and the genes related to fibroblasts. As an important protein of ECM, collagen has been proven to be closely related to the firmness of muscle in fish [26, 27]. In zebrafish, deposits of collagen were positively related to the increase in muscle firmness [27]. It was documented that downregulated expression of collagen and collagenase-3 enzyme elicited reduction in the firmness of atrophying muscle of rainbow trout [26]. Our results that the expressions of type I alpha-1 and alpha-2 and type II alpha-1a collagen are upregulated in crisp grass carp are consistent with the fact that collagen content in the muscle of crisp grass carp was 1.36 times greater than that of grass carp [17]. And the increase in the collagen content plays an important role in firmness increase of crisp grass carp muscle and resultant texture characteristics [2, 4]. For the upregulated expressions of type I and type II collagen, we speculate that the genes of INF-7 and procollagen-proline 4-hydroxylase (an enzyme hydrolyzing the collagen) probably play important roles in crisp grass carp. The basal expression of type I collagen was inhibited by INF-7 acting in not definitively located promoter region [28]. In the muscle of crisp grass carp, the mRNA level of INF-7 was 0.18 times that of grass carp and the transcription levels of type I and type II collagen increased. The results suggest that the inhibition of expression of INF-7 in the muscle of crisp grass carp promotes the synthesis of type I and type II collagen. The expression of procollagen-proline 4-hydroxylase was downregulated in the muscle of crisp grass carp, and this may help understand the increase in the expression of type I and type II collagen.

The increasing deposition of ECM in crisp grass carp muscle can also be suggested by enhanced TGF-β1 signaling. Enhanced TGF-β1 signaling in crisp grass carp could be demonstrated in the differential expressions including upregulated expression of TGFβ-induced factor homeobox-1 and downregulated expressions of both interferon regulatory factor-7 and interferon-inducible protein-kinase which are closely related to interferon inhibition of TGF-β1 signaling pathway. TGF-β1 is a pleiotropic cytokine known to play an important role in cell growth, embryonic development, and tissue repair and could induce the synthesis and accumulation of components of the extracellular matrix (ECM) in the muscle [29]. It was found that upregulated expression of TGF-β1 correlated with increase of ECM in the muscle [30]. In addition, the significantly upregulated expression of activin A receptor in crisp grass carp in this study, a downstream gene of TGF-β1 signaling pathway, further confirms enhanced TGF-β1 signaling.

Besides TGF-β1, the genes related to fibroblasts may play important roles in the increasing deposition of ECM. Fibroblasts were proven to produce an accumulation of fibrotic interstitial ECM components such as collagen and fibronectin [31], growth factors [32], and cytokines [33]. In the muscle of crisp grass carp, the mRNA level of fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 was more than that of grass carp, suggesting that fibroblast was activated. Some evidences had shown that MSTN could directly stimulate muscle fibroblast proliferation [34], and the enhancement in the transcripts levels of MSTN further demonstrated fibroblast proliferation in the muscle of crisp grass carp. Stromal cell-derived factor (SDF) was also involved in the activation, proliferation, and migration of fibroblast and secretion of ECM [35] and played important roles in fibrosis [36]. Both SDF-1 and SDF-4 had been demonstrated to be highly expressed in the muscle of crisp grass carp than those in grass carp, suggesting that these two genes may be responsible for the increased firmness in the muscle of crisp grass carp.

4.3. Genes Involved in Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis Pathway

Downregulated expressions of genes involved in glycolysis, as a major source of energy in the muscle, could result in the lower expression of myofiber proteins which were closely related to muscle firmness increase [21]. In this study, downregulated glycolysis/gluconeogenesis pathway in the crisp grass carp may contribute to the muscle firmness increase of crisp grass carp. The evidence that glycolysis pathway in the muscle of crisp grass carp is downregulated is the decrease in the expressions of five glycolytic enzymes in addition to aldehyde dehydrogenase which acts on products of glycolysis. The evidence that crisp grass carp have lower levels of anaerobic metabolism is that they have lower velocity of both glycolysis and TCA cycle. On the contrary, higher rates of aerobic metabolism in crisp grass carp are demonstrated by the upregulated expressions of mitochondrial genes. Larsson et al. also found that the firmness of Atlantic salmon muscle was associated with high rates of aerobic metabolism [21]. In addition, differential expression of genes involved in glucose utilization has also been found in the change of muscle texture under nutrition restriction [26, 37, 38]. However, the function and mechanism of glucose utilization acting in the muscle firmness increase still need further exploration.

4.4. Genes Involved in Calcium Metabolism

Calcium could activate the increase in the density of filamentous myosins [39], and the increasing density of filamentous myosins contributes to the muscle firmness increase [10]. The previous results that the calcium content in crisp grass carp [40] and the density of filamentous myosins were increased [17] could further help to understand the muscle firmness increase in crisp grass carp. In this paper, the expressions of seven genes related to calcium including calreticulin (CRT), calmodulin (CaM), and cadherin protein (Cad) were found with upregulated mRNA expression. CRT, as one of the major calcium-binding proteins of the endoplasmic reticulum, was involved in the regulation of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis and endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ storage capacity [41], and its overexpression increased calcium fluxes across endoplasmic reticulum [42]. CaM, a protein that binds calcium with high affinity and specificity, serves as an intracellular Ca2+-receptor and mediates the Ca2+ regulation of cyclic nucleotide and glycogen metabolism, secretion, motility, and Ca2+ transport [43]. Thus, an increase in the Ca2+ content of crisp grass carp muscle [40] further contributed to increased expression levels of calcium-dependent proteins including CaM and Cad [44]. In addition, downregulated expressions of three genes including desmocollin, guanylate cyclase activator, and zgc:136759 would help the study of calcium regulation in crisp grass carp.

4.5. Heterohybridization to Zebrafish cDNA Microarray and Its Application to Grass Carp

Affymetrix zebrafish chip has been proven to be a valid way to examine the gene expression profiling of grass carp muscle. Because DNA microarrays are unavailable for grass carp, the Affymetrix zebrafish chip was used in this study. Grass carp is near to the zebrafish in an evolutionary sense, and these two species were a family of Cyprinidae. The Affymetrix zebrafish array had been used to screen gene transcript profiles of grass carp recently, and the 416 genes of differential expressions were found to be related to the use of LS as an alternative dietary antibiotic in fish [45]. Use of cross-hybridization with microarrays for analysis of closely related species also had been reported by other researchers. A cDNA microarray from African cichlid fish, Astatotilapia burtoni, had been proven to be a powerful tool for analyzing the transcription profile of other cichlid species including Enantiopus melanogenys and Neolamprologus brichardi and Oreochromis niloticus [46]. The microarray composed of channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) transcripts was effectively used to analyze gene expression profiling of blue catfish (Ictalurus furcatus) [47]. The Affymetrix zebrafish array was also used to screen gene expression profiles of distantly related species, and it was found that 375 genes were significantly expressed in the muscle tissues of Chinese mandarin fish (Siniperca chuatsi) [48]. Such applications indicated that use of the zebrafish genome array could be a valid way to examine grass carp, and a conclusion was strongly supported in the current study by real-time RT-PCR validation.

In conclusion, during the muscle firmness increase from grass carp to crisp grass carp, a total of 127 transcripts were found to be upregulated and a total of 114 transcripts were downregulated. Strong correlation with muscle firmness increase of crisp grass carp was found for these genes from differentiation of muscle fibers and deposition of ECM, and also glycolysis pathway and calcium metabolism may contribute to muscle firmness increase. However, a number of genes with unknown functions may be related to muscle firmness, and these genes can be regarded as candidate markers of nutritional regulation of grass carp muscle firmness.

Acknowledgments

This investigation was supported by the earmarked fund for Modern Agro-Industry Technology Research System no. CARS-46-17, National Key Technology R&D Program (2012BAD25B04), and Project no. 10151038001000004 from Guangdong Natural Science Foundation.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Food and Agriculture Organisation . FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture. Rome, Italy: Department Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu Z., Ruan Z., Li B., Meng M., Zeng Q. Quality loss assessment of crisp grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus C. et V) fillets during ice storage. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation. 2013;37(3):254–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4549.2011.00643.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu Z. W., Li B. S., Ruan Z., Meng M. Y., Zeng Q. X. Differences in the physicochemical characteristcs between the muscles of Ctenopharyngodon idellus C. et V and Ctenopharygodon idellus . Modern Food Science and Technology. 2007;24(2):109–119. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin W.-L., Zeng Q.-X., Zhu Z.-W., Song G.-S. Relation between protein characteristics and tpa texture characteristics of crisp grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus C. et V) and grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus) Journal of Texture Studies. 2012;43(1):1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4603.2011.00311.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu E. M., Liu B. H., Wang G. J., et al. Molecular cloning of type I collagen cDNA and nutritional regulation of type I collagen mRNA expression in grass carp. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition. 2014;98(4):755–765. doi: 10.1111/jpn.12132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sylvia M. T. M., Graham T., Garcia S. Organoleptic qualities of farmed and wild salmon. Journal of Aquatic Food Product Technology. 1995;4(1):51–64. doi: 10.1300/J030v04n01_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnston I. A., Li X., Vieira V. L. A., Nickell D., Dingwall A., Alderson R., Campbell P., Bickerdike R. Muscle and flesh quality traits in wild and farmed Atlantic salmon. Aquaculture. 2006;256(1–4):323–336. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2006.02.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Webster C. D., Tidwell J. H., Goodgame J. S. Growth, body composition and organoleptic evaluation of channel catfish fed diets containing different percentages of distillers’ grains with solubles. Progressive Fish-Cultrist. 1993;55:95–100. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grigorakis K., Taylor K. D. A., Alexis M. N. Organoleptic and volatile aroma compounds comparison of wild and cultured gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata): sensory differences and possible chemical basis. Aquaculture. 2003;225(1–4):109–119. doi: 10.1016/S0044-8486(03)00283-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hatae K., Yoshimatsu F., Matsumoto J. J. Role of muscle fibers in contributing firmness of cooked fish. Journal of Food Science. 1990;55:693–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1990.tb05208.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hurling R., Rodell J. B., Hunt H. D. Fiber diameter and fish texture. Journal of Texture Studies. 1996;27(6):679–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4603.1996.tb01001.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnston I. A., Alderson R., Sandham C., Dingwall A., Mitchell D., Selkirk C., Nickell D., Baker R., Robertson B., Whyte D., Springate J. Muscle fibre density in relation to the colour and texture of smoked Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) Aquaculture. 2000;189(3-4):335–349. doi: 10.1016/S0044-8486(00)00373-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sigurgisladottir S., Sigurdardottir M. S., Ingvarsdottir H., Tprrisssen O. J., Hafsteinsson H. Microstructure and texture of fresh and smoked Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar L., fillets from fish reared and slaughtered under different conditions. Aquaculture Research. 2001;32(1):1–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2109.2001.00503.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnston I. A. Muscle development and growth: potential implications for flesh quality in fish. Aquaculture. 1999;177(1–4):99–115. doi: 10.1016/S0044-8486(99)00072-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Periago M. J., Ayala M. D., López-Albors O., Abdel I., Martínez C., García-Alcázar A., Ros G., Gil F. Muscle cellularity and flesh quality of wild and farmed sea bass, Dicentrarchus labrax L. Aquaculture. 2005;249(1–4):175–188. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2005.02.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palstra A. P., Planas J. V. Fish under exercise. Fish Physiology and Biochemistry. 2011;37(2):259–272. doi: 10.1007/s10695-011-9505-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin W.-L., Zeng Q.-X., Zhu Z.-W. Different changes in mastication between crisp grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus C.et V) and grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus) after heating: the relationship between texture and ultrastructure in muscle tissue. Food Research International. 2009;42(2):271–278. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2008.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adamidou S., Nengas I., Alexis M., Foundoulaki E., Nikolopoulou D., Campbell P., Karacostas I., Rigos G., Bell G. J., Jauncey K. Apparent nutrient digestibility and gastrointestinal evacuation time in European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax) fed diets containing different levels of legumes. Aquaculture. 2009;289(1-2):106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2009.01.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adamidou S., Nengas I., Henry M., Grigorakis K., Rigos G., Nikolopoulou D., Kotzamanis Y., Bell G. J., Jauncey K. Growth, feed utilization, health and organoleptic characteristics of European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax) fed extruded diets including low and high levels of three different legumes. Aquaculture. 2009;293(3-4):263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2009.04.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu Y. Q., Li D. Y., Zhao S. M., Xiong S. B. Effect of feeding broad bean on growth and flesh quality of channel catfish. Journal of Huangzhou Agricultural University. 2012;31(6):771–777. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larsson T., Mørkøre T., Kolstad K., Østbye T.-K., Afanasyev S., Krasnov A. Gene expression profiling of soft and firm Atlantic salmon fillet. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039219.e39219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Douglas S. E. Microarray studies of gene expression in fish. OMICS: A Journal of Integrative Biology. 2006;10(4):474–489. doi: 10.1089/omi.2006.10.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McPherron A. C., Lawler A. M., Lee S.-J. Regulation of skeletal muscle mass in mice by a new TGF-β superfamily member. Nature. 1997;387(6628):83–90. doi: 10.1038/387083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu J. Y., Casella J. F., Pollard T. D. Effect of capping protein, CapZ, on the length of actin filaments and mechanical properties of actin filament networks. Cell Motility and Cytoskeleton. 1999;42:73–81. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1999)42:1<73::AID-CM7>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wear M. A., Cooper J. A. Capping protein: new insights into mechanism and regulation. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2004;29(8):418–428. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salem M., Kenney P. B., Rexroad C. E., Yao J. Microarray gene expression analysis in atrophying rainbow trout muscle: a unique nonmammalian muscle degradation model. Physiological Genomics. 2006;28(1):33–45. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00114.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berger J., Berger S., Hall T. E., Lieschke G. J., Currie P. D. Dystrophin-deficient zebrafish feature aspects of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy pathology. Neuromuscular Disorders. 2010;20(12):826–832. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanaka S., Ramirez F. The first intron of the human α2(I) collagen gene (COL1A2) contains a novel interferon-γ responsive element. Matrix Biology. 2007;26(3):185–189. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andreetta F., Bernasconi P., Baggi F., Ferro P., Oliva L., Arnoldi E., Cornelio F., Mantegazza R., Confalonieri P. Immunomodulation of TGF-β1 in mdx mouse inhibits connective tissue proliferation in diaphragm but increases inflammatory response: implications for antifibrotic therapy. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2006;175(1-2):77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Passerini L., Bernasconi P., Baggi F., Confalonieri P., Cozzi F., Cornelio F., Mantegazza R. Fibrogenic cytokines and extent of fibrosis in muscle of dogs with X-linked golden retriever muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscular Disorders. 2002;12(9):828–835. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8966(02)00071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ignotz R. A., Massague J. Transforming growth factor-β stimulates the expression of fibronectin and collagen and their incorporation into the extracellular matrix. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1986;261(9):4337–4345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kasemkijwattana C., Menetrey J., Bosch P., Somogyi G., Moreland M. S., Fu F. H., Buranapanitkit B., Watkins S. S., Huard J. Use of growth factors to improve muscle healing after strain injury. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2000;(370):272–285. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200001000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vial C., Zúñiga L. M., Cabello-Verrugio C., Cañón P., Fadic R., Brandan E. Skeletal muscle cells express the profibrotic cytokine connective tissue growth factor (CTGF/CCN2), which induces their dedifferentiation. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2008;215(2):410–421. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao B. L., Kollias H. D., Wagner K. R. Myostatin directly regulates skeletal muscle fibrosis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(28):19371–19378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802585200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suzuki Y., Rahman M., Mitsuya H. Diverse transcriptional response of CD4+ T cells to stromal cell-derived factor (SDF)-1: cell survival promotion and priming effects of SDF-1 on CD4+ T cells. Journal of Immunology. 2001;167(6):3064–3073. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.6.3064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu J., Mora A., Shim H., Stecenko A., Brigham K. L., Rojas M. Role of the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis in the pathogenesis of lung injury and fibrosis. The American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 2007;37(3):291–299. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0187OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lecker S. H., Jagoe R. T., Gilbert A., Gomes M., Baracos V., Bailey J., Price S. R., Mitch W. E., Goldberg A. L. Multiple types of skeletal muscle atrophy involve a common program of changes in gene expression. The FASEB Journal. 2004;18(1):39–51. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0610com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raffaello A., Laveder P., Romualdi C., Bean C., Toniolo L., Germinario E., Megighian A., Danieli-Betto D., Reggiani C., Lanfranchi G. Denervation in murine fast-twitch muscle: short-term physiological changes and temporal expression profiling. Physiological Genomics. 2006;25(1):60–74. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00051.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herrera A. M., Kuo H., Seow C. Y. Influence of calcium on myosin thick filament formation in intact airway smooth muscle. American Journal of Physiology - Cell Physiology. 2002;282(2):C310–C316. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00390.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu B. H., Wang G. J., Yu E. M., Xie J., Yu D. G., Wang H. Y., Gong W. B. Comparison and evaluation of nutrition composition in muscle of grass carp fed with broad bean and common compound feed. South China Fisheries Science. 2011;7(6):58–65. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gelebart P., Opas M., Michalak M. Calreticulin, a Ca2+-binding chaperone of the endoplasmic reticulum. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2005;37(2):260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arnaudeau S., Frieden M., Nakamura K., Castelbou C., Michalak M., Demaurex N. Calreticulin differentially modulates calcium uptake and release in the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(48):46696–46705. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202395200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Means A. R., Dedman J. R. Calmodulin—an intracellular calcium receptor. Nature. 1980;285(5760):73–77. doi: 10.1038/285073a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aberle H., Schwartz H., Kemler R. Cadherin-catenin complex: protein interactions and their implications for cadherin function. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 1996;61(4):514–523. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4644(19960616)61:4<514::AID-JCB4>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chu W. Y., Liu X. L., Chen D. X., Shi J., Chen Y. H., Li Y. L., Zeng G. Q., Wu Y. A., Zhang J. S. Effects of dietary lactosucrose on the gene transcript profile in liver of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) Aquaculture Nutrition. 2013;19(5):798–808. doi: 10.1111/anu.12026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Renn S. C. P., Aubin-Horth N., Hofmann H. A. Biologically meaningful expression profiling across species using heterologous hybridization to a cDNA microarray. BMC Genomics. 2004;5(1):42–48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-5-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peatman E., Terhune J., Baoprasertkul P., Xu P., Nandi S., Wang S., Somridhivej B., Kucuktas H., Li P., Dunham R., Liu Z. Microarray analysis of gene expression in the blue catfish liver reveals early activation of the MHC class I pathway after infection with Edwardsiella ictaluri . Molecular Immunology. 2008;45(2):553–566. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chu W., Fu G., Chen J., Chen D., Meng T., Zhou R., Xia X., Zhang J. Gene expression profiling in muscle tissues of the commercially important teleost, Siniperca chuatsi L. Aquaculture International. 2010;18(4):667–678. doi: 10.1007/s10499-009-9289-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]