Abstract

Hierarchy can be conceptualized as objective social status (e.g., education level) or subjective social status (i.e., one’s own judgment of one’s status). Both forms predict well-being. This is the first investigation of the relative strength of these hierarchy-well-being relationships in the U.S. and Japan, cultural contexts with different normative ideas about how social status is understood and conferred. In probability samples of Japanese (N=1027) and U.S. (N=1805) adults, subjective social status more strongly predicted life satisfaction, positive affect, sense of purpose, and self acceptance in the U.S. than in Japan. In contrast, objective social status more strongly predicted life satisfaction, positive relations with others, and self acceptance in Japan than in the U.S. These differences reflect divergent cultural models of self. The emphasis on independence characteristic of the U.S. affords credence to one’s own judgment (subjective status) and the interdependence characteristic of Japan to what others can observe (objective status).

Keywords: Culture/Ethnicity, Culture and Self, Emotion, Interdependence, Social Status, Well-being

People high in psychological well-being have better job performance, motivation, relationships, and health (Deci & Ryan, 2001; Harter, Schmidt, & Keyes, 2002; Ryff, Singer, & Love, 2004; Segrin & Taylor, 2007). Here, we examine a powerful predictor of psychological well-being—social hierarchy, or rank in society—and investigate for the first time how cultural context influences this link. Specifically, we show that subjective social status, or people’s own views of where they stand in the social hierarchy, more strongly predicts well-being in the U.S. than in Japan. In contrast, objective social status (e.g., level of educational attainment) plays a relatively stronger role for well-being in Japan than in the U.S.

Indices of social rank as diverse as occupational status, income, educational attainment and self-rated position within the social hierarchy are all linked to well-being (Adler, Epel, Castillazzo, & Ickovics, 2000; Anderson, Kraus, Galinsky, & Keltner, 2012; Lorant et al., 2003). Those at the top of the social hierarchy are more optimistic, experience more positive and fewer negative emotions, and feel less threatened and anxious (Keltner, Gruenfeld, & Anderson, 2003). In contrast, people lower in social rank experience more adversity (Almeida, Neupert, Banks, & Serido, 2005) and are subject to negative stereotypes about their abilities (Croizet & Claire, 1998; Fiske, Cuddy, Glick & Xu, 2002). Given the pattern in these findings, understanding and assessing where people fit in their relevant social hierarchies is likely to be crucial in fostering psychological health and mitigating psychological dysfunction.

One’s social status or position in the hierarchy is multifaceted and can be captured in multiple ways. Indices include objective factors, such as educational attainment, income, and occupation, and also subjective factors, such as one’s self-rated position in the relevant hierarchy. We suggest that both objective and subjective forms of status are important for well-being, but that their relative power differs across cultures. We hypothesize that subjective social status carries greater weight in independent cultural contexts such as the U.S., which place greater emphasis on one’s own internal thoughts and feelings, than in interdependent cultural contexts such as Japan, where the self is construed as fundamentally connected to others and thus others’ views are crucial for well-being (Diener & Suh, 2000; Kitayama, Karasawa, Curhan, Ryff, & Markus, 2010). Because objective social status reflects markers of status that are visible to others and are agreed upon by social consensus, we hypothesize that objective status is a more powerful predictor in interdependent than independent cultural contexts.

Status and Well-being

In Western contexts, people with higher objective social status have better psychological well-being (Adler et al., 2000; Lorant et al., 2003; Marmot, Ryff, Bumpass, Shipley, & Marks, 1997). They typically control more resources and encounter fewer financial, social, and psychological stressors (Matthews, Gallo, & Taylor, 2010; Berkman, Glass, Brissette & Seeman, 2000). In addition, higher rank offers greater opportunities for self-realization and self-development (Dowd, 1990). More limited but consistent evidence exists for a similar objective social status-well-being link in Japan (Fukuda & Hiyoshi, 2012; Honjo et al., 2006). In Eastern contexts, objective hierarchies have even more legitimacy and positive resonance than they do in the West and are used to organize a wide array of everyday activities (Tu, 1991). People are well aware of their place in these hierarchies and are more comfortable with hierarchical social relations than Europeans and European Americas (e.g., Brockner, et al, 2001; Ho, 1995). Japan is a context with particularly strong norms about the importance of objective hierarchies in creating and maintaining the social order (Gelfand et al., 2011).

People’s subjective sense of their position in the social hierarchy is also a powerful predictor of well-being. Adler and colleagues’ pioneering studies reveal that individuals’ self-reported judgments of their position relative to others predicts psychological well-being as well or better than objective social status (Adler et al., 2000; Anderson et al., 2012; Kraus, Adler, & Chen, 2013; Demakakos, Nazroo, Breeze, & Marmot, 2008; Singh-Manoux, Adler, & Marmot, 2003). Two studies investigating these relationships in Japan found similar patterns (Honjo, Kawakami, Tsuchiya, & Sakurai, 2013; Sakurai, Kawakami, Yamaoka, Ishikawa, & Hashimoto, 2010).

No study has directly compared the strength of the relationships between either type of social status and well-being in the U.S. relative to Japan. As Inaba and colleagues (2005) note, the well-being-status relationships found in the West may not apply in other contexts such as Japan. In particular because of cultural variation in the importance of objective and subjective social status in the U.S. and Japan, the well-being-status relationships are unlikely to be equally powerful in each context. In Japan, as in the U.S., subjective social status offers the advantage of simultaneously indexing multiple status-relevant factors and capturing whatever status markers are most relevant in a particular context (Adler & Stewart, 2007; Leu et al., 2008). Yet, we suggest that the benefit of measures capturing individuals’ personal views of their status is likely more limited in Japan because of the powerful role of publically inscribed or objective hierarchy (e.g., educational attainment, status of company, etc.) in shaping most aspects of everyday life (Rai & Fiske, 2011).

Cultural Differences in Sources of Well-being

Well-being and its sources differ across cultural contexts. In Japan, well-being centers more around well-managed relationships with others, while in the U.S. it depends more on individuals’ personal feelings and emotions (Kitayama & Markus, 2000; Mesquita & Leu, 2007; Uchida, Townsend, Markus, & Bergseiker, 2009). These differences reflect the different models of self pervasive in these contexts (Markus & Kitayama, 2003). These models are inscribed in individual attitudes and values and are also built into the institutions, practices, and artifacts that organize everyday life (Markus & Conner, 2013). According to the independent model of self, normative in mainstream U.S. contexts, people are understood as fundamentally independent from others. Consequently, individuals’ own perceptions and subjective reactions are the primary determinants of thoughts, feelings, and actions, and their own internal psychological states are attended to and emphasized (Markus & Kitayama, 2010). As in all contexts, others’ judgments influence thought and behavior, but one’s own views are the most accessible referent for self-evaluation and accomplishment. Such a context affords self-rated (i.e., subjective) social status a particularly important role in well-being.

In contrast, according to the interdependent model of self that is normative in Japan, people are understood as fundamentally interconnected with important others. Self-assessment in Japan, therefore, is less about “what do I think or feel?” and more about “how am I viewed by others?” (Lebra, 2008). Accordingly, the effects of social approval or the “eyes of others” on individuals’ behavior are amplified (Kim, Cohen, & Au, 2010; Kitayama & Imada, 2008). Indeed, in interdependent cultures, public and institutionalized benchmarks of success that signal the community’s respect are primary referents for self-evaluation (Leung and Cohen, 2011; Wirtz & Scollon, 2012). Objective benchmarks are powerful because they reflect the relevant ingroups’ shared and normative understandings, made real in the world. Such a context affords objective social status, which is observable to others and reflects social consensus about the definition of success, a larger role in well-being than does an independent context.

Study Overview

The present research aimed to be the first study to (1) compare the strength of the relationship between objective social status and well-being in the U.S. and Japan, and (2) to compare the strength of the relationship between subjective social status and well-being in the U.S. and Japan. Furthermore, as our outcome, we used multiple well-validated measure of well-being (Deci & Ryan, 2001; Ryff, 1989). These included measures that captured hedonic well-being (i.e., happiness, feeling good) and eudaimonic well-being (i.e., meaning, purpose, and fulfillment). We predicted that subjective social status would be more strongly linked with well-being in the U.S. than in Japan, whereas objective social status would be more strongly linked with well-being in Japan than in the U.S. To test our hypothesis, we drew on representative survey data from the two nations.

Method

Samples

The U.S. data came from the second wave of the MIDUS (Midlife in the U.S.) national study conducted in 2004–2005 (75% longitudinal retention rate, adjusted for mortality). We used 1805 adults (aged 34–84) from the random-digit-dialing sample (Radler & Ryff, 2010). This sample included non-institutionalized, English-speaking adults randomly selected from working telephone banks in the 48 contiguous states. The Japanese sample (MIDJA) included 1027 adults (aged 30–79) randomly selected from the Tokyo metropolitan area (23 wards) in 2008–2010 (response rate = 56.2%). Respondents completed self-administered questionnaires; the Japanese version was back-translated and adjusted multiple times by native speakers to generate analogous meaning. The samples were comparable in terms of age, gender, and marital status (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and mean comparisons for the Japanese (N = 1,027) and U.S. (N = 1,805) sample.

|

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | U.S.

|

Japan

|

Mean comparisons

|

|||

| M | SD | M | SD | t | Sig. | |

| Age | 56.9 | 12.6 | 54.4 | 14.1 | 4.69 | *** |

| Gender | 0.55 | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.50 | n/a | * |

| Married | 0.67 | 0.47 | 0.69 | 0.46 | n/a | ns |

| Objective Social Status (educational attainment) | 4.58 | 1.66 | 4.24 | 1.69 | 5.25 | *** |

| Subjective Social Status (ladder) | 6.50 | 1.86 | 6.03 | 2.11 | 5.87 | *** |

| Life satisfaction | 7.84 | 1.55 | 6.13 | 2.06 | 23.13 | *** |

| Positive affect | 3.51 | 0.69 | 3.21 | 0.76 | 10.67 | *** |

| Autonomy | 5.33 | 1.00 | 4.38 | 0.76 | 28.66 | *** |

| Environmental mastery | 5.40 | 1.06 | 4.53 | 0.78 | 25.15 | *** |

| Personal growth | 5.45 | 1.01 | 4.82 | 0.81 | 18.01 | *** |

| Positive relations | 5.72 | 1.01 | 4.79 | 0.82 | 26.84 | *** |

| Purpose in life | 5.44 | 1.02 | 4.54 | 0.72 | 27.39 | *** |

| Self acceptance | 5.41 | 1.18 | 4.40 | 0.81 | 26.6 | *** |

Japanese (N = 1,027) and Americans (N = 1,805). Two-tailed independent sample t-tests were used for mean comparisons. Chi-square tests were used to determine mean group differences and the phi coefficient was used as a measure of association for gender (X2= 3.91, p = .05; phi = .04) and marital status (X2= 1.08, p = .30; phi = .02).

p < .001.

Social Status

Objective social status

Objective social status was indexed by educational attainment level (1 = 8th grade/junior high; 2 = some high school; 3 = high school graduate/G.E.D.; 4 = one of more years of college, no degree; 5 = two-year college degree/vocational school; 6 = four/five-year college bachelor’s degree; 7 = at least some graduate school). Educational attainment is the most frequently used indexed of socioeconomic status, as it is a precursor to occupation and income and is easily measured at individual level (as opposed to total household income, for example) (e.g., Lareau & Conley, 2008; Fiske & Markus, 2012).” Moreover among the three most commonly used indicators of social class status (education, income, occupation), education is the best predictor of a wide range of values and beliefs and is also the most closely associated with lifestyle, behavior and psychological functioning (e.g., Attewell & Newman, 2010; Reardon, 2011; Snibbe & Markus, 2005).

Subjective social status

Subjective social status was measured using the community ladder (Adler et al., 2000), a drawing of a 10-rung ladder with the instructions:

Think of this ladder as representing where people stand in their communities. People define community in different ways; please define it in whatever way is most meaningful to you. At the top of the ladder are the people who have the highest standing in their community. At the bottom are the people who have the lowest standing in their community. Where would you place yourself on this ladder? Please check the box next to the rung on the ladder where you think you stand at this time in your life, relative to other people in the community with which you most identify.

To ensure that the ladder assessed a similar construct in the two contexts, multiple rounds of translation and back-translation with native English and Japanese speakers made sure the word “community” was comparable in both nations. Further, we examined how subjective social status ratings correlated with other measures in the MIDJA and MIDUS surveys. Across domains, the correlations in both nations were similar. The highest correlations (all ps < .01) for both nations were with the generativity scale (e.g., “Many people come to you for advice” (Japan r = .44, U.S. r = .41), the self esteem scale (Japan r = .42, U.S. r = .43), and a rating of satisfaction with one’s current financial situation (Japan r = .40; U.S. r = .30).

Well-Being

We indexed eight scales covering distinct forms of both hedonic well-being (i.e., life satisfaction, positive affect) and eudaimonic well-being (i.e., the six psychological well-being subscales) (Deci & Ryan, 2001). Life satisfaction was a one-item rating of current life satisfaction (0 = worst possible, 10 = best possible). The positive affect measure was based on the widely-used PANAS (Watson, Clark, & Carey, 1988), which also has been validated in Japan (Sato, & Yasuda, 2001). Respondents rated the frequency (1 = none of the time, 5 = all of the time) of experiencing each of the following states during the previous two weeks: cheerful, in good spirits, extremely happy, calm and peaceful, satisfied, full of life, enthusiastic, attentive, proud, confident, active, full of life, close to others, and like you belong (Japan α = .94; U.S. α = .94).

The six psychological well-being subscales (Ryff, 1989) each represented the respective 7-item mean of responses to a 7-point Likert-type scale: autonomy (e.g., “My decisions are not usually influenced by what everyone else is doing”; Japan α = .70, U.S. α = .71), environmental mastery (e.g., “In general, I feel I am in charge of the situation in which I live”; Japan α = .73, U.S. α = .78), personal growth (e.g., “For me, life has been a continuous process of learning, changing, and growth”; Japan α = .74, U.S. α = .75), positive relations with others (e.g., “I know that I can trust my friends, and they know they can trust me”; Japan α = .76, U.S. α = .78), purpose in life (e.g., “Some people wander aimlessly through life, but I am not one of them”; Japan α = .56, U.S. α = .70), and self acceptance (e.g., “When I look at the story of my life, I am pleased with how things have turned out”; Japan α = .78, U.S. α = .84).

Finally, we created a composite well-being measure by averaging each participant’s within-culture standardized scores on the eight well-being measures listed above.

Control variables

Our analyses controlled for demographic variables (age, gender, marital status) shown to predict well-being (e.g., Cleary, Zaborski, & Ayanian, 2004; Inaba et al., 2005).

For all variables, higher numbers indicated more of a given construct. Missing data were limited (<5% for each variable), so no further adjustments were made.

Results

Two-tailed independent samples t-tests indicated that U.S. respondents scored higher than Japanese respondents on both status measures and on well-being measures (see Table 1). Bivariate correlations between status and well-being measures were nearly all significant. For the U.S., objective social status correlated with all well-being variables except positive relations (range: .06 to .25), and subjective social status correlated with all well-being variables (range: .32 to .47), ps < .05. For Japan, objective social status correlated with all well-being variables except positive affect (range: .07 to .24), and subjective social status correlated with all well-being variables (range: .26 to .39), ps < .05. See Table 2 for more details.

Table 2.

Subjective social status predicts mental health indicators beyond the effects of objective SES in Japan (N = 1,027, Panel A) and the U.S. (N = 1,805, Panel B).

| Panel A. U.S. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Objective Social Status

|

Subjective Social Status

|

|||||

| b | t | Sig. | b | t | Sig. | |

|

|

|

|||||

| Life satisfaction | 0.01 | 0.89 | 0.19 | 15.92 | *** | |

| Positive affect | 0.02 | 1.10 | 0.20 | 16.47 | *** | |

| Autonomy | 0.01 | 0.92 | 0.16 | 17.89 | *** | |

| Environmental mastery | 0.05 | 4.06 | *** | 0.20 | 16.98 | *** |

| Personal growth | 0.11 | 8.37 | *** | 0.19 | 15.45 | *** |

| Positive relations w/others | 0.00 | −0.15 | 0.20 | 16.78 | *** | |

| Purpose in life | 0.07 | 4.84 | *** | 0.19 | 15.71 | *** |

| Self acceptance | 0.24 | 17.60 | *** | 0.19 | 15.71 | *** |

| Well-being composite | .08 | 3.85 | *** | .47 | 21.55 | *** |

| Panel B. Japan | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Objective Social Status

|

Subjective Social Status

|

|||||

| b | t | Sig. | b | t | Sig. | |

|

|

|

|||||

| Life satisfaction | .10 | 5.44 | *** | 0.11 | 8.07 | *** |

| Positive affect | .02 | .93 | 0.11 | 7.74 | *** | |

| Autonomy | .02 | 1.61 | 0.13 | 12.42 | *** | |

| Environmental mastery | .08 | 4.30 | *** | 0.17 | 12.49 | *** |

| Personal growth | .10 | 5.65 | *** | 0.15 | 10.97 | *** |

| Positive relations w/others | .09 | 5.15 | *** | 0.17 | 12.31 | *** |

| Purpose in life | .09 | 4.68 | *** | 0.12 | 8.33 | *** |

| Self acceptance | .31 | 16.75 | *** | 0.12 | 8.05 | *** |

| Well-being composite | .18 | 5.95 | *** | .41 | 14.45 | *** |

Unstandardized regression coefficients are presented. All analyses controlled for age, gender, and marital status. Degrees of freedom (df) were 2722 except for life satisfaction (2708), positive affect (2716), and purpose in life (2721).

p < .001.

To test our hypotheses, we used hierarchical linear regressions to explore cultural differences in the relative influence of objective and subjective social status in predicting well-being. Age, gender, and marital status were entered into the model in Step 1, followed by objective social status in Step 2, then subjective social status in Step 3 (following past precedent (e.g., Adler et al., 2000) to ensure its predictive influence was independent of objective social status), then culture (dummy-coded) and its interactions with both objective and subjective social status in Step 4 and Step 5, respectively. To reduce multicollinearity, mean-centered objective and subjective social status scores were used to compute the two interaction terms (Cohen & Cohen, 1983; Cronbach, 1987). Separate regressions were conducted to predict the eight well-being outcomes (also standardized within-nation).

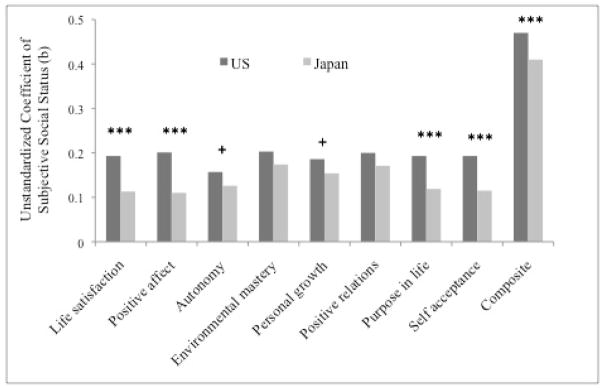

As hypothesized, subjective social status showed a robust pattern of stronger effects on well-being in the U.S. than Japan, while, in contrast, objective social status showed a robust pattern of stronger effects on well-being in Japan than in the U.S. Specifically, the associations between subjective social status and the well-being outcomes that were stronger in the U.S. were those that predicted life satisfaction (b = −.08, t(2708) = −4.35, p < .001), positive affect (b = −.09, t(2716) = −4.94, p < .001), purpose in life (b = −.07, t(2721) = −3.99, p < .001), and self acceptance (b = −.08, t(2722) = −4.35, p < .001). Notably, on two additional measures the subjective social status x culture interaction resulted in marginal statistical significance in the same direction: autonomy (b = −.03, t(2722) = −1.65, p < .10), and personal growth (b = −.03, t(2722) = −1.74, p < .09). Finally, the association between subjective social status and the well-being composite was significantly stronger in the U.S. than in Japan, b = −.09, t(2733) = −4.02, p < .001 (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1.

Subjective social status shows a robust pattern of stronger effects on psychological well-being in the U.S. (n = 1,805) than Japan (n = 1,027). Unstandardized coefficients are presented, controlling for age, gender, and marital status. +p < .10., ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

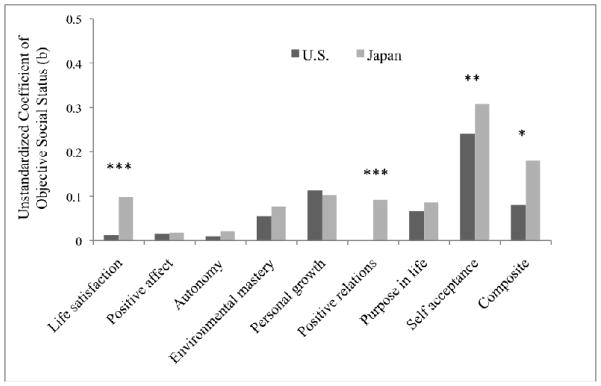

In contrast, the results of the objective social status analyses tended to show the opposite cultural pattern. The associations between objective social status and the well-being outcomes were significantly stronger in Japan than in the U.S. for life satisfaction (b = .09, t(2708) = 3.91, p < .001), positive relations (b = .09, t(2722) = 4.30, p < .001), and self-acceptance (b = .07, t(2722) = 3.16, p < .01). In addition, the association between objective social status and the well-being composite was significantly stronger in Japan than in the U.S., b = .05, t(2733) = 2.34, p < .05.1 For both objective social status and subjective social status, the non-significant culture interactions nearly always followed the hypothesized direction of effects. (See Figure 2.)2

Figure 2.

Objective social status shows a robust pattern of stronger effects on psychological well-being in Japan (n = 1,027) than in the U.S. (n = 1,805). Unstandardized coefficients are presented, controlling for age, gender, and marital status.

Discussion

We show that hierarchy matters for well-being in both the U.S. and Japan, and break new ground by demonstrating that the strength of associations between different forms of hierarchy and well-being varies systematically by cultural context. While subjective social status significantly predicted both hedonic and eudaimonic outcomes in Japan and the U.S., the strength of these associations was relatively stronger in the U.S.—significantly so for life satisfaction, positive affect, purpose in life, and self acceptance. The reverse was true for objective social status, which predicted life satisfaction, positive relations with others, and self acceptance significantly more strongly in Japan than in the U.S.

Our findings are consistent with previous research suggesting that the beliefs and practices of U.S. culture sanction an independent model of the self in which one’s own subjective judgments —rather than others’ judgments—are the primary referent for the evaluation of self worth and accomplishment (Markus & Kitayama, 2010). Eleanor Roosevelt’s claim, “Nobody can make you feel inferior without your consent,” succinctly expresses this widespread American sentiment.

The comparatively stronger role of objective social status in Japan relative to the U.S. supports past research indicating that the beliefs and practices of East Asian cultures, including Japan, foster an interdependent model of the self in which the socially consensual, publically accorded aspects of the self (i.e., objective factors such as one’s degree or position in company, etc.) are the primary referent for self-assessment and are reflected in everyday social interactions (e.g., Leung and Cohen, 2011; Rai & Fiske, 2011). Relative to the U.S., in Japan, one’s own personal, possibly idiosyncratic, criteria for where the self stands in relation to others are relatively less central in self-evaluation.

Other recent evidence also suggests a differential emphasis on objective, externally observable factors in East Asia versus more subjective factors in the West (e.g., Kim et al., 2010; Wirtz & Scollon, 2012). For example, Park and colleagues (in press) found that anger expression is predicted by objective status in Japan, but by subjective status in the U.S. The present study, paired with this past research, may help explain the relatively greater importance assigned indices of position in various social hierarchies such as grades or admission to prestigious universities among people from Asian and Asian American contexts compared to those in matched Northern American contexts (Chao & Tseng, 2002; Chua, 2011). In Asian and Asian American contexts, such objective status indicators are more tightly linked to well-being.

Local vs. Global Status

Our measures of social status, the ladder and level of educational attainment, differ on multiple dimensions. We have focused on the distinction between objective and subjective markers of status. However, another notable characteristic of the ladder measure included here is that it captures local as opposed to global status (Anderson et al., 2012). Specifically, it asks people about their position within their local community rather about their position compared to people in their country overall or to people in general. Questions about status relative to an important reference group are powerful predictors of well-being in East Asian as well as Western cultural contexts (Oshio, Nozaki, & Kobayashi, 2011). Although, subjective markers of status are relatively more powerful in the U.S., status within the local context is relatively more important in Japan, where the boundary between ingroup and outgroup is a strong and significant division. Interdependence thus refers not to interdependence with people in general but specifically to interdependence with others in close relationships and important groups (Markus & Kitayama, 2010). The importance of the local community may explain why our ladder measure, which uses community as a referent, is a stronger predictor of well-being than education in Japan (as it is in the U.S., as well). The fact that this measure captures local rather than global status may help it to predict well-being. Our data only included one ladder measure, but future research might compare the predictive power of global and local objective and subjective markers of status for well-being. Objective indices of local status should predict well-being more strongly than objective indices of global status or subjective indices of local status in Japan.

Well-being in Japan

The finding that objective social status predicted well-being more strongly in Japan than in the U.S. emerged most robustly on three well-being indices—positive relations with others, self acceptance, and life satisfaction—that might be especially relevant in interdependent cultural contexts in which connection to others is a primary social goal (Oishi & Diener, 2001; Uchida, Norasakkunkit, & Kitayama, 2005). Positive relations explicitly implicates others, and self acceptance is likely to rely heavily on others in interdependent cultural contexts where cues from others are a primary referent for self esteem and self regard (e.g., Heine, Lehman, Markus, & Kitayama, 1999). Finally, Japanese ratings of life satisfaction, a broad construct that allows respondents to bring to mind whatever components of well-being are most relevant in their cultural contexts, are also likely to invoke social relationships.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although laboratory experiments offer some evidence to support our implicit claim that social status affects well-being in the U.S. (e.g., Anderson et al., 2012; Mendelson, Thurston, & Kubzansky, 2008), additional experimental work in Japan as well as longitudinal research would further illuminate cultural differences (or similarities) in the causal direction and mechanisms underlying these findings. Future work might also include measures that would allow a more fine-grained measure of objective status (e.g., university attended) and explore the relationship between hierarchy and other types of well-being using other measures besides those available in the samples used here. These include varieties of well-being that are more prevalent in Japan, such as sympathy with others (Kitayama & Markus, 2000) or minimalist happiness (Kan, Karasawa, & Kitayama, 2009), as well as measures of mental illness.

Implications and Conclusion

This study has important implications for efforts to improve psychological well-being. For example, in the U.S., many popular methods in mental health counseling focus on teaching people to cognitively restructure or reappraise how they feel and think about themselves and their behavior. However, in contexts such as Japan where interdependent models of self are normative, mature people are expected to be aware of and behave in accordance with their place in various objective hierarchies. Changing how they view themselves without attending to the views of others may be decidedly less effective in improving mental health. Well-being interventions might focus instead on helping people raise their objective status through effort and concrete achievements or else on accepting and adjusting to their position in the social order (e.g., Weisz, Rothbaum & Blackburn, 1984).

In summary, we conclude that both U.S. Americans and Japanese make social comparisons that affect their well-being, but the criteria for such comparisons tend to be more external in Japan and more internal in the U.S. While human hierarchies may be a universal feature of human life, our findings suggest that how they are determined and maintained and how they relate to well-being is culturally-contingent.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (5R37AG027343) to conduct a study of Midlife in Japan (MIDJA) for comparative analysis with MIDUS (Midlife in the U.S., P01-AG020166).

Footnotes

The data from the U.S. (MIDUS II) and Japan (MIDJA) are available from the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR; http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/).

We operationalized objective social status as level of educational attainment (see methods). However, operationalizing it as a composite of level of educational attainment and occupational status (three levels: manual/blue collar/service, non-manual/white collar/clerical, and managerial/professional) yields the same set of significant results, except that objective social status no longer predicts self-acceptance more strongly in Japan than in the U.S.

Our primary interest was in the relative role of subjective and objective status across cultures (i.e., extent to which subjective social status predicted well-being in the U.S. relative to Japan and the extent to which objective social status predicted well-being in the U.S. relative to Japan). However, it should also be noted that across cultures, subjective social status predicted well-being more strongly than objective social status. Specifically, using the well-being composite as an outcome measure, the subjective social status x objective social status interaction is significant, b = .01, t(2724) = 2.24, p < .05. The culture x subjective social status x objective social status is not significant [b = −.002, t(2723) = −.25, p = .81], indicating that the relatively stronger role of subjective social status in predicting well-being is not moderated by culture. Importantly, the critical two-way interactions (i.e., culture x subjective social status, culture x objective social status) remain significant even with when the subjective social status x objective social status interaction is taken into account.

Contributor Information

Katherine B. Curhan, Stanford University

Cynthia S. Levine, Stanford University

Hazel Rose Markus, Stanford University.

Shinobu Kitayama, University of Michigan.

Jiyoung Park, University of Michigan.

Mayumi Karasawa, Tokyo Woman’s Christian University.

Norito Kawakami, University of Tokyo.

Gayle D. Love, University of Wisconsin, Madison

Christopher L. Coe, University of Wisconsin, Madison

Yuri Miyamoto, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Carol D. Ryff, University of Wisconsin, Madison

References

- Adler NE, Epel ES, Castellazzo G, Ickovics JR. Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy white women. Health Psychology. 2000;19(6):586–592. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.6.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler NE, Stewart J. The MacArthur scale of subjective social status. MacArthur Research Network on SES & Health; 2007. Retrieved from http://www.macses.ucsf.edu/Research/Psychosocial/subjective.php. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, Neupert SD, Banks SR, Serido J. Do daily stress processes account for socioeconomic health disparities? Journal of Gerontology: Series B. 2005;60(SI2):S34–S39. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.Special_Issue_2.S3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson C, Kraus MW, Galinsky AD, Keltner D. The local-ladder effect: Social status and subjective well-being. Psychological Science. 2012;23(7):764–771. doi: 10.1177/0956797611434537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attewell S, Newman KS. Growing gaps: Educational inequality around the world. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Glass T, Brisette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science and Medicine. 2000;51(6):843–857. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockner J, Ackerman G, Greenberg J, Gelfand MJ, Francesco AM, Chen ZX, Leung K, Bierbrauer G, Gomez C, Kirkman BL, Shapiro D. Culture and procedural justice: The influence of power distance on reactions to voice. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2001;37(4):300–315. doi: 10.1006/jesp.2000.1451. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chao R, Tseng V. Parenting of Asians. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting. Vol. 4. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 2002. pp. 59–93. [Google Scholar]

- Chua A. Battle hymn of the tiger mother. New York: Penguin; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cleary PD, Zaborski LB, Ayanian JZ. Sex differences in health over the course of midlife. In: Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC, editors. How healthy are we? A national study of well-being at midlife. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2004. pp. 37–63. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Croizet JC, Claire T. Extending the concept of stereotype threat to social class: The intellectual underperformance of students from low socioeconomic backgrounds. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1998;24(6):588–594. doi: 10.1177/0146167298246003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach L. Statistical tests for moderator variables: Flaws in analysis recently proposed. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;102(3):414–417. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.102.3.414. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:141–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demakakos P, Nazroo J, Breeze E, Marmot M. Socioeconomic status and health: The role of subjective social status. Social Science and Medicine. 2008;67:330–340. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Suh EM, editors. Culture and subjective well-being. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dowd JJ. Ever since Durkheim: The socialization of human development. Human Development. 1990;33(2–3):138–159. doi: 10.1159/000276507. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske ST, Cuddy AJC, Glick P, Xu J. A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82(6):878–902. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske ST, Markus HR, editors. Facing social class: How societal rank influences social interaction. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda Y, Hiyoshi A. Influences of income and employment on psychological distress and depression treatment in Japanese adults. Environmental Health and Preventative Medicine. 2012;17(1):10–17. doi: 10.1007/s12199-011-0212-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand MJ, Raver JL, Nishii L, Leslie LM, Lun J, Yamaguchi S. Differences between tight and loose cultures: A 33-nation study. Science. 2011;332(6033):1100–1104. doi: 10.1126/science.1197754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter JK, Schmidt FL, Keyes CL. Well-being in the workplace and its relationship to business outcomes: A review of the Gallup studies. In: Keyes CLM, Haidt J, editors. Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. pp. 205–224. [Google Scholar]

- Heine SJ, Lehman DR, Markus HR, Kitayama S. Is there a universal need for positive self-regard? Psychological Review. 1999;106(4):766. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.106.4.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho DYF. Self-hood and identity in Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism, and Hinduism: Contrasts with the West. Journal of the Theory of Social Behavior. 1995;25(2):115–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5914.1995.tb00269.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Honjo K, Kawakami N, Takeshima T, Tachimori H, Ono Y, Uda H, Hata Y, Nakane Y, Nakane H, Iwata N, Furukawa TA, Wantanabe M, Nakamura Y, Kikkawa T. Social class inequalities in self-rated health and their gender and age group differences in Japan. Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;16(6):223–232. doi: 10.2188/jea.16.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honjo K, Kawakami N, Tsuchiya M, Sakurai K. Association of subjective and objective socioeconomic status with subjective mental health and mental disorders among Japanese men and women. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s12529-013-9309-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba A, Thoits PA, Uenoc K, Gove WR, Evenson RJ, Sloan M. Depression in the United States and Japan: Gender, marital status, and objective status patterns. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61(11):2280–2292. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan C, Karasawa M, Kitayama S. Minimalist in style: Self, identity, and well-being in Japan. Self and Identity. 2009;8:300–317. doi: 10.1080/15298860802505244. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keltner D, Gruenfeld DH, Anderson C. Power, approach, and inhibition. Psychological Review. 2003;110(2):265–284. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.110.2.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y-H, Cohen D, Au W-T. The jury and abjury of my peers: The self in face and dignity cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;98(6):904–916. doi: 10.1037/a0017936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S, Karasawa M, Curhan KB, Ryff CD, Markus HR. Independence and interdependence predict heatlh and wellbeing: Divergent patterns in the United States and Japan. Frontiers in Psychology. 2010;1:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2010.00163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S, Markus HR. The pursuit of happiness and the realization of sympathy: Cultural patterns of self, social relations, and well-being. In: Diener E, Suh EM, editors. Culture and subjective well-being. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2000. pp. 113–161. [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S, Imada T. Defending cultural self: A dual-process model of agency. In: Urdan T, Maehr M, editors. Advances in motivation and achievement. Vol. 15. Elsevier; 2008. pp. 171–207. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus MW, Adler N, Chen TWD. Is the association of subjective SES and self-rated health confounded by negative mood? An experimental approach. Health Psychology. 2013;32(2):138–145. doi: 10.1037/a0027343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lareau A, Conley D. Social class. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lebra TS. The Japanese self in cultural logic. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Leu J, Yen IH, Gansky SA, Walton E, Adler NE, Takeuchi DT. The association between subjective status and mental health among Asian immigrants: Investigating the influence of age at immigration. Social Science and Medicine. 2008;66(5):1152–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung AKY, Cohen D. Within- and between-culture variation: Individual differences and the cultural logics of honor, face, and dignity cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;100(3):507–526. doi: 10.1037/a0022151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorant V, Deliege D, Eaton W, Robert A, Phillippot P, Ansseau M. Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;157(2):98–112. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, Conner AC. Clash! Eight cultural conflicts that make us who we are. New York: Penguin (Hudson Street Press); 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review. 1991;98(2):224–253. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, Kitayama S. Models of agency: Sociocultural diversity in the construction of action. In: Murphy-Berman V, Berman J, editors. The 49th Annual Nebraska symposium on motivation: Cross-cultural differences in perspectives on self. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 2003. pp. 1–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, Kitayama S. Cultures and selves: A cycle of mutual constitution. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2010;5(4):420–430. doi: 10.1177/1745691610375557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M, Ryff CD, Bumpass LL, Shipley M, Marks NF. Social inequalities in health: Next questions and converging evidence. Social Science and Medicine. 1997;44(6):901. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00194-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews KA, Gallo LC, Taylor SE. Are psychosocial factors mediators of socioeconomic status and health connections? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1186:146–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson T, Thurston RC, Kubzansky LD. Affective and cardiovascular effects of experimentally-induced social status. Health Psychology. 2008;27(4):482–489. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.4.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesquita B, Leu J. The cultural psychology of emotions. In: Kitayama S, Cohen D, editors. Handbook for cultural psychology. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 734–759. [Google Scholar]

- Oishi S, Diener E. Goals, culture, and subjective well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27(12):1674–1682. doi: 10.1177/01461672012712010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oshio T, Nozaki K, Kobayashi M. Relative income and happiness in Asia: Evidence from nationwide surveys in China, Japan, and Korea. Social Indices Research. 2011;104:351–367. [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Kitayama S, Markus HR, Coe CL, Miyamoto Y, Karasawa M, Curhan K, Love GD, Kawakami N, Boylan JM, Ryff CD. Social status and anger expression: The cultural moderation hypothesis. Emotion. doi: 10.1037/a0034273. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radler BT, Ryff CD. Who participates? Accounting for longitudinal retention in the MIDUS national study of health and well-being. Journal of Aging and Health. 2010;22(3):307–331. doi: 10.1177/0898264309358617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai TS, Fiske AP. Moral psychology is relationship regulation: Moral motives for unity, hierarchy, equality, and proportionality. Psychological Review. 2011;118(1):57–75. doi: 10.1037/a0021867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon SF. The widening gap between the rich and the poor: New evidence and possible explanations. In: Duncan GJ, Murname RJ, editors. Whither opportunity? Rising inequality, schools and children’s life chances. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2011. pp. 91–116. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57(6):1069–1081. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Singer BH, Love GD. Positive health: Connecting well-being with biology. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B, Biological Sciences. 2004;359(1449):1383–1394. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai K, Kawakami N, Yamaoka K, Ishikawa H, Hashimoto H. The impact of subjective and objective status on psychological distress among men and women in Japan. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70(11):1832–1839. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato A, Yasuda A. Development of the Japanese version of Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) scales. Japanese Journal of Personality. 2001;9(2):138–139. [Google Scholar]

- Segrin C, Taylor M. Positive interpersonal relationships mediate the association between social skills and psychological well-being. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43(4):637–646. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2007.01.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh-Manoux A, Adler NE, Marmot MG. Subjective status: its determinants and its association with measures of ill-health in the Whitehall II study. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56(6):1321–1333. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snibbe A, Markus HR. You can’t always get what you want: Educational attainment, agency and choice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:703–720. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.4.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu W. Cultural China: The periphery as the center. Journal of the American Academy of Arts and Science. 1991;120(2):1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Uchida Y, Norasakkunkit V, Kitayama S. Cultural constructions of happiness: Theory and empirical evidence. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2005;5:223–239. [Google Scholar]

- Uchida Y, Townsend SSM, Markus HR, Bergsieker H. Emotions as within or between people? Cultural variation in lay theories of emotion expression and inference. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2009;35:1427–1439. doi: 10.1177/0146167209347322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Carey G. Positive and negative affectivity and their relation to anxiety and depressive disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97(3):346–353. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.97.3.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JJ, Rothbaum Fm, Blackburn TC. Standing out and standing in: The psychology of control in America and Japan. American Psychologist. 1984;39(9):955–969. doi: 0.1037/0003-066X.39.9.955. [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz D, Scollon CN. Culture, visual perspective, and the effect of material success on perceived life quality. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2012;43(3):367–372. doi: 10.1177/0022022111432292. [DOI] [Google Scholar]